Abstract

Signals from the tumor microenvironment (TME) have a profound influence on the maintenance and progression of cancers. Chronic inflammation and the infiltration of immune cells in breast cancer (BC) have been strongly associated with early carcinogenic events and a switch to a more immunosuppressive response. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the most abundant stromal component and can modulate tumor progression according to their secretomes. The immune cells including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), and helper T cell (Th)), monocyte-infiltrating cells (MICs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), mast cells (MCs), and natural killer cells (NKs) play an important part in the immunological balance, fluctuating TME between protumoral and antitumoral responses. In this review article, we have summarized the impact of these immunological players together with CAF secreted substances in driving BC progression. We explain the crosstalk of CAFs and tumor-infiltrating immune cells suppressing antitumor response in BC, proposing these cellular entities as predictive markers of poor prognosis. CAF-tumor-infiltrating immune cell interaction is suggested as an alternative therapeutic strategy to regulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment in BC.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequent cancer among women worldwide representing a global health problem. It was estimated in 2018 that more than 2.1 million women were newly diagnosed with BC, with 600,000 deaths [1] and 2.3 million new cases are estimated by 2030 [2]. The survival rate of patients has improved in recent decades due to early diagnosis and better access to treatments, but it is still lower in developing regions [2]. Although early-stage and nonmetastatic BC is curable, advanced disease with distant organ metastasis is considered incurable with current therapies [3].

BC can be classified into five subtypes according to the expressions of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), acting as predictive factors and guiding therapy decision-making [3]. These subtypes are (1) luminal A-like HER2− (ER+/PR+/HER2−/Ki67−), (2) luminal B-like HER2− (ER+/PR+/HER2−/Ki67+), (3) luminal B-like HER2+ (ER+/PR+/HER2+/Ki67+), (4) HER2-enriched or nonluminal subtype (ER−/PR−/HER2+), and (5) triple-negative BC (TNBC) (ER−/PR−/HER2−). Most patients are luminal A-like subtype, accounting for 60-70% of total cases, whereas the TNBC subtype is less frequent with around 10-15% incidence [3]. Based on histological subtypes, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are the most commonly studied, with IDC the most common invasive BC, having an incidence of around 72-80% of total BC cases, whereas DCIS is the most frequent subtype of noninvasive BC accounting for a quarter of all cases [4]. DCIS is not generally considered as a life-threatening disease, although it can increase the risk of tumor progression to IDC.

Physiologically, the mammary gland tissue dynamically changes throughout a women's life, that is, the remodeling that occurs during pregnancy, lactation, involution (a process triggered postweaning), and regression. The immune system of the normal breast shares similarities with other mucosal systems, such as the intestine or respiratory mucosa, and plays a crucial role in protection and maintenance of the normal glandular structure [5]. It is also witnessed that carcinogenesis develops spontaneous breast adenocarcinomas in immunodeficient mice compared to immunocompetent mice [6].

It is well accepted that immune cells infiltrating into the tumor microenvironment (TME) have opposing functions such as T cells (cytotoxic CTLs, T helper type 1 (Th1)), natural killer cells (NKs), B cells, and mononuclear cells (M1-classically activated macrophages and mature dendritic cells (DCs)) contributing to tumor eradication, whereas Th2, regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and alternatively activated macrophages (M2) or tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have protumorigenic functions [7, 8]. The low immunogenicity of BC and immunosuppressive TME limit immunotherapy benefits targeting the adaptive immune system, such as checkpoint inhibitors [9]. To achieve successful immunotherapy in BC, the functions of cellular components in TME that determine tumor immune response evasion need to be fully understood. Among these components, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor-infiltrating immune cells are our focus in this review. CAFs are involved in BC initiation, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, playing a critical role in metabolic TME reprogramming and therapy resistance [10–13], secreting growth factors, cytokines, and hormones, together with extracellular matrix (ECM) paracrine effects and mechanical stimuli determining cancer development. Additionally, microenvironmental events including angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, ECM remodeling, cancer-associated inflammation, and metabolism reprogramming have premalignancy potency through signaling pathway crosstalk among CAFs, cancer cells, and ECM [13–16].

In this review article, the role of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and CAFs in BC is examined, including basic knowledge on immune cells and CAF phenotypes. Additionally, we discuss CAF immunosuppressive effect contributing to immune escape of BC. We hope that understanding the interaction between tumor cells and TME components (CAFs and immune cells) will bring forth new patient management and targeting therapies within BC.

2. Tumor Microenvironment of Breast Cancer (BC)

In BC TME, a combination of heterogeneous cell types communicates with cancer cells, including tumor-infiltrating immune cells, adipocytes, pericytes/endothelial cells, CAFs, and noncellular components such as ECM, cytokines, and growth factors [17–19]. The impact of cells of the immune system and CAFs on cancer progression, drug, and immunotherapeutic responses is discussed.

2.1. Immune Cells in BC Tissues with Their Anti- or Protumoral Functions and Roles in Prognosis and Therapy Response

In normal breast epithelium, the immune cell population varies according to the reproductive state. In nulliparous mouse models, immature DCs and RORγT+-Th17 cells are predominant. During lactation, DCs acquire a tolerogenic phenotype with decreased T cell activation, extending during weaning by FOXP3+ Treg expansion. These activated and tolerogenic programs seem to assure protection from bacterial and self-antigens during epithelial cell death, occurring after lactation and involution [5].

During acute lobulitis, an increased infiltration of CD45+ leucocyte (including CD4+-T cells, CTLs, and CD19+/CD20+-B cells) is seen compared to normal tissue without DC or CD68+-monocyte/macrophage changes [20].

Diverse immune cells are recruited during tumor development and progression in the mammary gland [20]. In benign lesions, high monocyte/macrophage and DC infiltration is seen, whilst decreased CTLs and absence of B cells are associated with increased risk of BC [21, 22]. In in situ transition of carcinoma to invasive carcinoma, changes in conventional cell populations (decreased CTLs and increased Tregs) can promote an immunosuppressive environment with immune escape [23]. This process is characterized by the loss of immunostimulatory molecules (i.e., major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, transporter-associated antigen processing (TAP) subunit 1), increased expression of immunoinhibitory molecules (i.e., programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G)), and altered apoptosis component expression (i.e., Fas and FasL) [5], leading to disease progression and treatment failure. We review in this section the main immune cell populations and their role in prognosis and therapy response.

2.1.1. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Subsets

Lymphocytes present in tumor tissues, namely, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), are highly heterogeneous playing a crucial role in host antigen-specific tumor immune response. TILs have pro- or antitumor properties depending on T cell subsets in distinct cancer tissues with antitumor subsets, mainly CTLs and Th1 cells, whereas Th2, Th17, and Treg exhibit opposing roles.

In breast TME, TILs are predominantly activated T lymphocytes (CD3+/CD56−, CD4+, or CD8+-T cells) [10], with their increase associated with good prognosis in TNBC patients [24–26] and chemotherapy response in BC patients [24, 27–29].

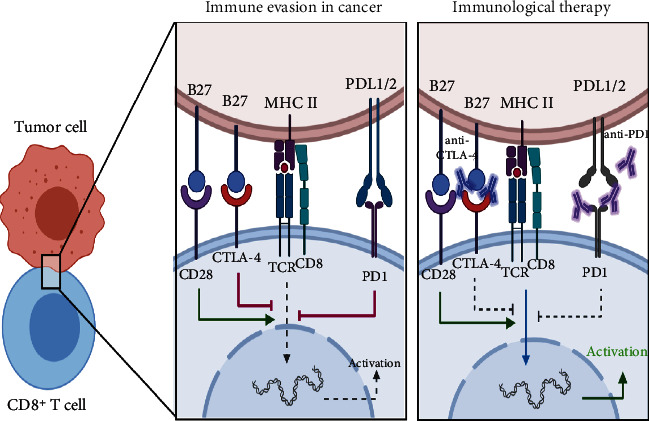

Using TIL gene signatures in luminal A and luminal B BC, predictive responses of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD1 (Figure 1), allow stratification into three subtypes: (1) Lum 1, with low TILs and immune gene levels, (2) Lum 2, high expression of STAT1 and interferon-stimulated genes with TP53 somatic mutations, and (3) Lum 3, high level of TILs and immune-related/immune checkpoint gene expression (i.e., PD-L1 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4)) and chemokine genes (i.e., CXCL9 and CXCL10) and their receptors [30]. Lum 1 has low TILs whilst Lum 3 has high TILs with high immune checkpoint expressions, which may imply that Lum 3 may have better predictive response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), the drug that blocks immune checkpoint molecules resulting in restoration of the immune system function, than Lum 1. TILs recognize small peptide presented through MHC class I/II, with costimulatory signals necessary to modulate T cell activation. Indeed, the interaction between B7 and CD28 on TILs is a positive activation signal; however, in Lum 3 BC, the CTLA-4 (CD28 competitive receptor) and PD1/PD-L1 pathway in immune cells and endothelial cells delivers an inhibitory signal (Figure 1). Targeting immune checkpoints CTLA-4 and PD1/PDL-1 can be used for different cancer treatments, including BC [31–35]. Effects of ICI or immune cell therapy are diminished by immunosuppressive TME status. Therefore, to enhance this immune therapy's efficacy in breast cancer, the combination with chemotherapy is a plausible option [36].

Figure 1.

Targeting checkpoints of T cell in Lum 3 breast cancer. TILs recognizing small peptide presented through MHC class I/II, with costimulatory signals necessary to modulate T cell activation. Indeed, the interaction between B7 and CD28 on TILs is a positive activation signal; however, in Lum 3 BC, the CTLA-4 (CD28 competitive receptor) and PD1/PD-L1 pathway (immune and endothelial cells) delivers an inhibitory signal. Targeting immune checkpoints CTLA4 and PD1/PDL-1 can be used for different cancer treatments, including BC [31–35].

Another important antitumor cell is CTLs, inducing tumor cell lysis through perforin and granzyme release inducing cell apoptosis [37, 38]; however, during cancer progression, they become dysfunctional and exhausted due to TME immune-related tolerance and immunosuppression [39].

It is well accepted that high intratumor CTLs and memory TILs are associated with improved prognosis [38], as with Th1 cell in ER− and TNBCs, which secrete several cytokines/chemokines, activating and recruiting CTLs, together with NK cells and M1 macrophages to eradicate breast tumor cells [40]. Thus, the presence of follicular Th-CXCL13+ cells can predict good survival and prognosis in BC patients [41, 42].

In opposition, Th2 mainly produces interleukin (IL-10), modulating the TME immunosuppressive profile to inhibit antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and effector cell function [40, 43]. Th17 is another subset promoting tumor growth and angiogenesis [44, 45], although whilst priming CTLs with antitumor activity and favorable prognosis [46–49], their role in cancer remains controversial [50]. Infiltration of IL-17/IL-17A-secreting cells is associated with poor prognosis in BC patients [51–53], enhancing tumor migration, invasion, and chemotherapy resistance [54, 55]; the IL-17B/IL-17 B receptor (IL-17RB) axis is associated with poor prognosis and chemoresistance [56, 57], through the NF-κB/Bcl-2 antiapoptotic signaling pathway [58], becoming an attractive therapeutic target [59].

Tregs represent a minor CD4+-T cell population, maintaining immune homeostasis by inhibiting effector T cells [60], being increased in nearly all cancers associating with metastasis, tumor recurrence, and treatment resistance [61]. FOXP3+ is an indicator of Treg activity, tumor progression, and metastasis [62], with its suppression, together with programmed death 1 (PD1), T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3, and CTLA-4, assuring the increased immunotherapy response [61] (Figure 1), relapse-free survival (RFS), and overall survival (OS) in BC patients [63]. Treg-enriched TME potentiates immunosuppressive cells, i.e., CAFs, cancer cells, TAMs and MDSCs, whilst suppressing immunostimulatory cells, i.e., CTLs and NKs [61]. Nonetheless, Th2-derived IL-4 mediates Treg conversion to Th9 subset [64] with antitumor function increasing DC survival [65]. Finally, tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes regulate cancer progression via IL-10 production, although no consensus at present exists on their benefit as a prognosis marker [66].

2.1.2. Mononuclear Infiltrating Cells

Mononuclear myeloid cells are a heterogeneous population of bone marrow-derived cells which include monocytes, terminally differentiated macrophages, and DCs. Myeloid cells promote cancer progression by either directly interacting with tumor cells or supporting a tumor stroma that promotes tumor growth, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, and metastasis [67] and additionally suppressing tumor immunity [68]. The combined expression of high IL-1β and IL-6, but low IL-10 in stromal mononuclear inflammatory cells, associates with good prognosis and long relapse-free survival in breast carcinoma patients [69].

TAMs are a major constituent of TME in BC, mostly displaying the M2 phenotype with immunosuppressive activity, directly correlating with poor prognosis, activating cancer stem cells, cancer cell invasion, and tumor angiogenesis, and suppressing antitumor CTL functions [70].

Another important cell present in BC is DCs, classified into two major subsets: conventional DCs (cDCs, also known as myeloid DCs or classical DCs (cDCs)) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) producing type I interferon (IFN) in response to nucleic acids [71]. As the conventional type 1 DC (cDC1) subset is superior in antigen cross-presentation (a process of exogenous antigen presentation on MHC class I), cDCs control tumor progression, resulting in CTL priming and activation. Moreover, the cDC1 subset is important in the immune control of tumor by enhancing local cytotoxic T cell function, making them significant in immune checkpoint blocking therapy [72, 73]. In TNBC, cDCs expressing activation marker CD11c+ directly correlate with TILs, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell counts, highlighting the potential therapeutic options to modulate their recruitment and function [74]. DCs from human primary luminal and TNBC tissues are enriched in vascular wound healing/ECM pathways and immunological IFN pathways, respectively. Additionally, the type of tumor impacts on the diversity of DC subset correlating with disease outcome [75], therefore providing potential targets and biomarkers to evaluate immune status of BC TME.

Unlike cDCs, pDCs migrate to lymphoid organs and peripheral blood upon development. Infiltration of pDCs into cancer tissues is associated with poor prognosis correlating with BC lymph node metastasis, with participation of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemokine axis or stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha (SDF-1α) [76]. High CXCL12/SDF-1 level is seen in metastatic lymph nodes and CXCR4 upregulation in cancer cell lines exposed to pDC conditioned media. Finally, the immunosuppressive TME alters DC differentiation into tolerogenic regulatory DCs [77], characterized by decreased DC maturation marker content and promoting Treg expansion [78–80].

2.1.3. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of myeloid cells, contributing to an immune suppressive/anergic and tumor permissive environment [81] through inhibitory cytokines and other substances [82], thus promoting cancer progression and metastasis [81, 83], although there is no consensus for MDSC expression markers in tumor [84, 85]. MDSCs are usually absent in healthy individuals, appearing only in cancer and pathological conditions associated with chronic inflammation or stress [86]. This occurs in surgical removal of primary tumor in a xenograft mammary cell carcinoma murine model, demonstrating that MDSC infiltration is crucial to promote lung metastasis [87], by secreting transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and IL-10 inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Thus, biological MDSC depletion therapy is a promising treatment strategy to prevent immune evasion after mastectomy in BC. Elevated circulating MDSCs in peripheral blood of BC patients was found directly correlated with cancer stage and metastasis [88, 89], but information on the role of MDSCs in human BC is limited and requires more studies.

2.1.4. Mast Cells (MCs) and Natural Killer Cells (NKs)

Mast cells (MCs) are granulocyte-derived myeloid cells, containing histamine and heparin-rich granules, classically associated with allergic disorders. They display 2 phenotypes producing different mediators with opposite roles in tumorigenesis (antitumorigenic MC1 and protumorigenic MC2), depending on the biochemical milieu of the TME and tumor cells themselves [90, 91]. MCs are recruited by several cancer cell-derived cytokines and chemokines (i.e., osteopontin, CXCL8, CCL2, CXCL1, and CXCL10) into TME and can directly interact with infiltrated immune cells, tumor cells, and ECM [90]. MC1 are cytotoxic producing granzyme B, IL-9, and histamine, which induces DC maturation and inhibits tumor growth in murine models. In contrast, MC2 produces a variety of angiogenic and metastatic substances, i.e., VEGFs, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), TGF-β, and cytokines (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-13) [90].

Peripheral to mammary adenocarcinoma [92], MCs contribute to tumor invasiveness and metastatic spread through the secretion of MMPs and tryptase which promote ECM disruption [91, 93–96] and differentiation of myofibroblast [97, 98]. Additionally, MCs contribute to neovascularization by releasing classical (i.e., VEGF, FGF-2, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and IL-6) and nonclassical proangiogenic factors (mainly tryptase and chymase) [99]. Tryptase and chymase are suggested to be involved in cancer progression [100]. However, the infiltration of chymase-positive and tryptase-positive MCs in BC tissues is significantly higher in luminal A and luminal B subtypes compared to TNBC and HER2+ subtypes [101]. This study showed that higher MC numbers are associated with a less aggressive cancer type, suggesting that these MCs relate with more favorable cancer immunophenotype and might be beneficial prognostic indicators. The controversial findings may be due to the variation in the subpopulation of MCs and location of the cells in cancer tissue.

Natural killer cells (NKs) are a major antitumor component of the innate immune response. Similar to CTLs, NK-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity depends on stimulatory and inhibitory signaling balance, such as cytokines (i.e., IFN and IL-2), affecting activating (i.e., NKG2D and CD161), inhibitory NK receptors (i.e., CD158a and CD158b), and signaling molecules [102]. As demonstrated in chronic viral infection, autoimmunity, and transplantation, NKs limit T cell function by cytokines, interactions with NKG2D and NKp46 receptors, or perforin-mediated T cell death [103]. In BC, NKs could enhance the activity of HER2 therapeutic antibodies by coupling NK cell antitumor function with immune checkpoint blocking, stimulatory antibodies, cytokines, or toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists [104]. The expression of a high proportion of ligands for NK-activating receptors positively correlates with survival indicators; however, a restricted number of ligands associate with worse prognosis, becoming potential biomarkers of BC progression [105].

2.2. Tumor Microenvironment and CAFs in BC

CAFs are derived from normal resident fibroblasts, cancer cells, adipocytes, and endothelial cells [18] with cancer stem cells differentiated into BC CAFs, via a paracrine effect of cancer cell-derived osteopontin [106]. CAFs are critical cells in metabolic TME reprogramming and therapy resistance in BC as they promote tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [10–13].

2.2.1. CAF Markers and Their Important Impact in BC Progression

Breast CAFs differentially express genes compared to normal fibroblasts, accounting for BC occurrence and progression [107], thus becoming predictive CAF molecular markers in tumor progression. In BC, CAFs are heterogeneous and divide into 4 population groups: CAF-S1 to CAF-S4, according to differential activation marker expression mainly including α-smooth muscle actin (ASMA), fibroblast activation protein (FAP), PDGF receptor β (PDGFRβ), fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1), caveolin-1 (CAV-1), and CD29, with all correlating with poor prognosis (Table 1). All CAF subsets have low CAV-1 levels. The CAF-S1 subset mostly expresses all 6 markers, with especially FAP and ASMA highly expressed; the CAF-S2 subset expresses low levels of the 6 markers; the CAF-S3 subset is ASMA- and FAP-negative, but positive for the remaining 4 markers; and the CAF-S4 subset is characterized with no FAP, but high ASMA and CD29 [108]. Regarding localization, CAF-S1 and CAF-S4 are mainly in TNBC tumors, with HER2+ tumors additionally presenting CAF-S4. CAF-S3 has juxtatumoral localization in HER2+ and TNBC tumors. Lastly, CAF-S2 is in both tumor and juxtatumor compartments, mainly in the luminal A subtype [108]. Meta-analysis showed that increased number of activated tumor-infiltrating fibroblasts significantly correlated with poor clinical outcome of BC patients [109]. Additionally, CAFs with high ASMA and low high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) expression in cancer cells predict OS of invasive ductal BC patients [110]. Therefore, tenascin (TNC) overexpression (an ECM glycoprotein) is a poor prognosis factor [111], with FSP-1+ or podoplanin+ CAFs also associated with poor OS in BC patients [109]. Furthermore, CD10+ and GPR77+ CAFs promote tumor formation and chemoresistance by providing a survival niche for cancer stem cells [112]. CD44 is another cancer stem cell marker in CAFs, related to cancer cell survival and drug resistance [113]. Finally, CAFs expressing PDGFRβ associate to metastasis and reduced tamoxifen response [114]. The vimentin- (VIM-) positive fibroblasts showed spindle cells in cytology of BC tissues [115]. Additionally, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) was observed in most of the fibroblasts in BC, especially luminal A subtype [116]. Since TME participates in several processes of tumor progression, the CAF tumorigenic functions highlight the importance of their targeting as a useful strategy to overcome BC.

Table 1.

Markers of CAFs and the correlated biological function and function of CAFs on tumor promotion and immunosuppression in BC.

(a).

| Category | Markers (Ref) |

|---|---|

| Characteristic of CAFs | ASMA/CAV-1/CD29/FAP/FSP-1/PDGFRβ [108], VIM [115], CD10 [112] |

| Poor prognostic CAFs | ASMA/HMGB1 [110], COX-2 [159], CXCL-1 [126], FSP-1/podoplanin [109], HDAC6 [159], LC3/Snail1/TLR-4 [131], TNC [111], VIM [115] |

| Chemoresistance induction CAFs | CD10 [112], CD44 [113], GPR77 [112], IL-6 [118], PDGFRβ [114], HMGB1 [133], IL-7 [117] |

| Immune cell suppression CAFs | IL-10 [40, 43], IL-12/IL-23 [160], Chi3L1 [161], CXCL12/SDF-1 [108], CXCL16 [162] |

(b).

| CAF-derived substances | Target cells | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1 | Cancer cells | Decrease TGF-β signaling, promote tumor progression | [126] |

| CXCL8/IL-8 | Cancer cells | Mediate the prometastatic activities | [123] |

| CXCL12/SDF-1α | CD4+CD25+ Tregs | Attract, increase survival and promote differentiation to a regulatory phenotype | [108] |

| MDSCs | Recruit and exert tumor-promoting effects | [163] | |

| CXCL16 | Monocytes | Promote stroma activation in TNBC | [162] |

| Chi3L1 | CD8+CD4+ T lymphocytes | Enhance tumor infiltration and promote Th1 phenotype | [161] |

| Macrophages | Recruit and differentiate into M2-like phenotype | [161] | |

| TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12p70 | T lymphocytes | Secrete IFN-α and IFN-γ, induce CTL responses | [164] |

| IL-6 | Cancer cells | Induce EMT and promote tumor progression | [165] |

| IL-32 | Cancer cells | Promote cancer cell invasion | [127] |

| Leptin | Cancer cells | Promote cancer growth and progression Enhance cancer cell motility and invasiveness |

[128, 129] |

| MCP-1, SDF-1 | Macrophages | Recruit and differentiate into M2-like phenotype | [166] |

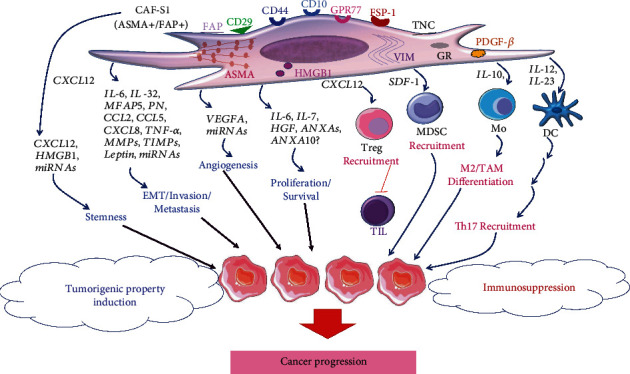

2.2.2. Secreted Substances from CAFs in BC

The most significant effect of CAFs is the secretion of tumor-promoting cytokines and chemokines, many of them playing a role in BC (Figure 2). One of them, CXCL12/SDF-1, shows strong expression in IL-7-producing fibroblasts, with the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis impacting tumor cell stemness promoting BC growth [117]. CAF-derived IL-6 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) induce androgenic enzymes contributing to intratumoral androgen metabolism in ER− BC patients [118]. The matricellular protein periostin (PN), secreted mainly by CAFs, binds to cancer cell surface receptors activating progression in invasive ductal breast carcinoma (IDC), showing increased PN levels compared to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [119]. Interestingly, high CAF-derived PN levels in IDC correlate with increased tumor malignancy grade and shorter patient OS, suggesting PN participation in IDC progression [119]. CAF-secreted microfibrillar-associated protein 5 (MFAP5) promotes cancer cell EMT marker upregulation, migration, and invasion via the Notch1 pathway [120, 121]. Prometastatic chemokines CXCL8 (IL-8), CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)), and CCL5 (RANTES) are upregulated in TNBC cell lines cocultured with primary CAFs from BC patients, acquiring invasive properties mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha- (TNF-α-) induced Notch1 activation [122, 123]. Moreover, MMPs expressed by the BC stroma correlate with metastasis [124], such as CAF-derived MMP-9, MMP-11, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2) associating with poor prognosis in luminal A tumors [125].

Figure 2.

CAF markers, CAF-derived substances, and their tumor-promoting functions of aggressive CAFs in BC, CAF-S1, with positive stains of ASMA and FAP. CAFs can also produce a variety of cytokines/chemokines into TME, promoting cancer aggressiveness by direct effect on tumor cells to induce tumorigenic properties, i.e., stemness, EMT/invasion/metastasis, cell growth, and angiogenesis. Lastly, some substances can indirectly activate cancer progression through immune cells, thus modulating the immunosuppressive condition in BC tissues.

Elevated CXCL1 in BC stroma correlates with increased tumor grade, disease recurrence, and poor patient survival [126] and inversely correlates with TGF-β signaling component expression. Additionally, CAF-inhibited TGF-β signaling in vitro increases CXCL1 expression, suggesting a contribution in BC progression [126]. Another CAF-derived cytokine promoting BC cell invasion is IL-32, binding to cell membrane integrin β3 to activate downstream p38 MAPK signal transduction [127]. The adipocyte-derived cytokine, leptin, influences BC cell proliferation [128] enhancing ER signaling and mediated tumor-stroma interaction by short autocrine loop. Finally, CAFs secrete leptin and express its receptor, enhancing BC cell motility and invasiveness [129].

Autophagy, a self-degradative process, regulates tissue homeostasis and intracellular energy source and participates in tumor recurrence/prognosis [130]. Autophagic CAFs, with increased LC3II (autophagosome protein) expression, release HMGB1 activating TLR4 in luminal BC cells, enhancing stemness and tumorigenicity, and predicting increased relapse rate and poor prognosis [131]. In TNBC, CAF autophagy enhances cell proliferation and the EMT process (migration, invasion), through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [132].

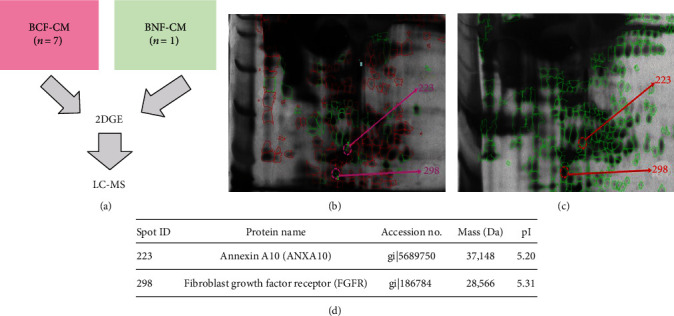

All the above has led our group to study breast CAFs isolated from fresh cancer tissues [133] and their secreted substances. Utilizing two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE), followed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS), we found annexin A10 (ANXA10) and FGF receptor (FGFR) upregulation (Figure 3). Accordingly, ANXA are a family of closely related calcium- and membrane-binding proteins playing important roles in calcium signaling, cell division, apoptosis, and cell differentiation [134]. In prostate cancer, ANXA1 stimulates cell proliferation and dedifferentiation of cancer cells to stem-like cells [135]. ANXA3 is overexpressed in lung cancer CAFs, playing an important role in chemoresistance [136]. By interacting with cancer cells, extracellular CAF vesicles (containing ANXA6) induce aggressive pancreatic ductal carcinoma [137]. Additionally, ANXA10 correlates with the progression of pancreatic early lesions towards ductal adenocarcinoma [138]. In serous epithelial ovarian cancer, high ANXA10 level was found and correlated with chemotherapeutic response [139]. It has also been proposed as the poor prognostic marker in several cancers, i.e., serous epithelial ovarian carcinoma, papillary thyroid cancer, and perihilar and distal cholangiocarcinoma [139–141]. Though no information is available on ANXA10 in BC to date, it possibly plays critical roles in disease aggressiveness.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE) and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) of breast CAF conditioned-medium (BCF-CM). (a) The primary culture fibroblasts including 7 BCF-CM and 1 breast normal fibroblast-conditioned medium (BNF-CM). 100 μg of each CM was prepared and applied to a 7 cm linear pH3-10, immobilized pH gradient (IPG) (GE Healthcare) strip. The first dimensional separation was performed at 20°C for 14 h in 3 steps including (1) 500 V for 1 h, (2) 1,000 V for 1 h, and (3) 5,000 V for 2-3 h. The second dimensional separation was performed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE at 150 V for 2 h. Gels were stained with silver (PlusOne staining kit, GE Healthcare) for 5 h. The gels were scanned by a Typhoon Laser Scanner (GE Healthcare). Protein spots were detected and percentages of the spot volume were calculated with Image Master 2D platinum program. (b, c) The representative gels of BNF-CM and BCF-CM, respectively. Spots no. 223 and 298 are found in only BCF-CM but not in BNF-CM. (d) Potential cancer-associated substances from breast CAFs determined by LC-MS. The protein spots in the gels from (b) and (c) were digested with trypsin. 100 μl of 3% H2O2 was added, removed, and dehydrated with 100 μl of 100% acetonitrile (ACN). Reduction was performed by adding 10 mM DTT in 10 mM NH4HCO3 and incubated at 56°C for 1 h. The solution was removed and replaced by adding 100 mM iodoacetamide in 10 mM NH4HCO3 and then dehydrated with 100% ACN. Digestion was performed by incubating with 20 ng/μl trypsin (Promega Corporation). 10 mM NH4HCO3 was added on gel pieces and incubated at 37°C overnight. The proteins were extracted from gels by adding 0.1% formic acid (FA) in 50% CAN and resuspended with 0.1% FA in LC-MS water before injection into the LC-MS (SYNAPT™ HDMS Mass Spectrometer, Water Corp, UK) (lab data).

Upregulation of FGFR can undergo shedding from CAFs, although FGF5 (a receptor ligand) is released from CAFs inducing FGFR2 expression in HER2+ BC cells resulting in HER targeted therapy resistance [142]. FGFR1 amplification occurs most frequently in patients with luminal B-like BC and appears to correlate with patient's poor prognosis, although with no statistical significance [143]. FGF overproduction may autocrinally activate FGFR expression rendering its shedding out into the TME; thus, the FGF/FGFR axis in BC offers target molecules to attenuate cancer progression [144]. Potentially, the combinations of anti-FGFR or anti-FGF therapies with checkpoint inhibitors can improve survival and quality of life of BC patients with novel and increasingly accurate therapeutic strategies.

Studies reveal a paracrine effect of CAF secreted factors over tumor cells enhancing therapeutic resistance through the evasion of apoptotic cell death [145]. HMGB1, a CAF-mediated protein, induces doxorubicin (a chemotherapeutic used to treat BC) resistance through autophagy induction [133]. Moreover, CAF-derived IL-6 secretion induces resistance to trastuzumab (a monoclonal antibody against HER2) by cancer stem cell expansion and apoptosis reduction via NF-κB, JAK/STAT3, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways [146]. Therefore, a novel strategy reverting trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ BC could be the combination of an anti-IL-6 antibody with these specific pathway inhibitors [146]. When cancer cells are cocultured with CAFs, tumor cells show chemoinsensitivity typical of aggressive BC [147], partly due to chemotherapy-induced metabolic and phenotype transformation of healthy fibroblasts into CAFs. This generates a nutrient and inflammatory cytokine-enriched environment, activating stemness in adjacent BC cells [148]. A combined drug approach, bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor) and panobinostat (a histone deacetylase inhibitor), synergistically decreases patient-derived CAF viability by inducing caspase-3-mediated apoptosis [149].

Other important mediators of intracellular communication currently emerging are exosomes, which affect BC progression by horizontally transferring microRNAs (miRs), mRNAs, and proteins [150]. Differential expression profile analysis identified three miRs (miR-21, miR-378e, and miR-143) increased in exosomes from breast CAFs compared to normal fibroblast, proposing their role in stemness and EMT induction in BC cell lines [151]. Breast stromal fibroblasts can secrete the proangiogenesis protein vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) which can be repressed by p16(INK4A) [152]. The above evidence supports the potential therapeutic strategies targeting breast CAFs, offering new tools in BC therapy [153, 154].

3. CAF Immunosuppressive Effect in BC

Immune modulation in breast TME plays a central role in determining disease outcome and immunotherapy response, in particular immune checkpoint modulators [155]. Accordingly, CAFs are key modulators of TME and immune response, secreting soluble molecules, such as cytokines/chemokines (refer to Table 1, Figure 2). This process allows CAFs to create immunological barriers against CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses [39]. Targeting CAFs with an on-shelf antifibrotic agent, TGF-β antagonist, combined with doxorubicin, inhibits tumor growth and metastasis synergistically [156]. Additionally, elimination of FAP+ CAFs in vivo shifted the immune microenvironment from Th2 to Th1 polarization, suggesting CAFs as attractive targets in metastatic BC [157]. Several clinical trials are ongoing concerning the role of the immune system in BC editing, with potential impact of immunotherapy [36]. Specifically, the CAF-S1 subtype in BC increases recruitment and differentiation of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in TME, through CXCL12/SDF1-α leading to the inhibition of effector T cell function [108].

Alternatively, CAF activation positively correlates with increased CD163+ TAM infiltration and lymph node metastasis in TNBC patients [158], being prognostic factors for disease-free survival.

An interesting epigenetic mediator is fibrotic histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), programming an immunosuppressive TME that reduces antitumor immunity, possibly a good target enhancing BC immunotherapy [159]. Genetic or pharmacologic disruption of HDAC6 in CAFs delays tumor growth, inhibits tumor recruitment of MDSCs and Tregs, alters macrophage phenotype switch, and increases CD8+ and CD4+-T cell activation in vivo [159]. Prostaglandin E2/cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) is the main target of HDAC6 in CAFs, and COX2 overexpression in HDAC6-knockdown CAFs reinstates fibroblast immunosuppressive properties.

Finally, TME-secreted substances also affect DC function in some cancers [160]. Accordingly, cervical cancer cells regulate DC production of IL-23 and IL-12 in DC/fibroblast cocultures through IL6/C/EBPβ/IL1β promoting Th17 cell expansion, although reducing antitumor Th1 differentiation during cancer progression [160].

4. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

A successful cancer therapeutic strategy using the immune system as a target requires understanding of cellular components in TME. Characteristics of CAFs and their secreted substances in each BC type are not only useful for being targets of treatment but also prognostic and predictive factors. According to secretory substances, cytokines/chemokines, together with exosomes containing miRs, mRNAs, and proteins, CAFs become key modulators for cancer progression and immune cell polarization, resulting in protumoral or immunosuppressive status in the TME. The use of appropriate biomarkers, resulting from cancer cell-immune cell-CAF crosstalk, will identify promising cases responding to therapy, enabling a suitable therapeutic strategy. Lastly, understanding the molecular mechanisms of complex interactions between CAFs and immune cells is needed to fill the knowledge gap, thus providing potential targets for improved cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the FONDECYT Grant No. 11190990 (MDlF), FONDECYT Grant No. 3190931 (GL), and “National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research REDES No. 180134 (PCI) Chile” for supporting collaborative networks between the authors from Chilean and Thai institutions. This study was funded by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation, National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (Grant number RSA6280091) Thailand and Research Grant, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University (R016033015) to CT, and ANID (National Research and Development Agency from the Chilean Government; Program of International Cooperation to Support for the Formation of International Networks between Research Centers) (Grant number 180134) to MAH.

Abbreviations

- ASMA:

α-Smooth muscle actin

- M2:

Alternatively activated macrophages

- APCs:

Antigen-presenting cells

- BC:

Breast cancer

- CAFs:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- CAV-1:

Caveolin-1

- Chi3L1:

Chitinase 3-like 1

- M1:

Classically activated macrophages

- COX:

Cyclooxygenase

- CTLs:

Cytotoxic T cells

- CTLA-4:

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- DCs:

Dendritic cells

- DCIS:

Ductal carcinoma in situ

- HER2:

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ER:

Estrogen receptor

- ECM:

Extracellular matrix

- FAP:

Fibroblast activation protein

- FGF:

Fibroblast growth factor

- FSP-1:

Fibroblast-specific protein-1

- FOXP3:

Forkhead box P3

- Th17:

Helper T17

- HGF:

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HMGB1:

High-mobility group box 1

- HDAC6:

Histone deacetylase 6

- HER-2:

Human epithelial growth factor receptor-2

- HLA:

Human leukocyte antigen

- IFN:

Interferon

- IL:

Interleukin

- DCIS:

Invasive ductal breast carcinoma

- LC-MS:

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- MHC:

Major histocompatibility complex

- MMPs:

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MCs:

Mast cells

- MFAP5:

Microfibrillar-associated protein 5

- MCP-1:

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MICs:

Monocyte-infiltrating cells

- MDSCs:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- NKs:

Natural killer cells

- OS:

Overall survival

- PN:

Periostin

- PDGF:

Platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFRβ:

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β

- PR:

Progesterone receptor

- PD1:

Programmed death 1

- PD-L1:

Programmed death-ligand 1

- Tregs:

Regulatory T cells

- RFS:

Relapse-free survival

- SDF-1:

Stromal cell-derived factor 1

- TGF-β1:

Transforming growth factor-β1

- TNBC:

Triple-negative breast cancer

- TAMs:

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TILs:

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TME:

Tumor microenvironment

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- TNC:

Tenascin C

- TIMP-2:

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2

- TLR:

Toll-like receptor

- TGF-β1:

Transforming growth factor-β1

- TAP:

Transporter-associated antigen processing

- 2DGE:

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

Data Availability

Data availability is upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Siriraj Institutional Review Board COA no. Si520/2010) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Chanitra Thuwajit contributed in conceptualization; Marcela A. Hermoso, Chanitra Thuwajit, and Marjorie De la Fuente had the idea for the article; Chanitra Thuwajit, Jarupa Soongsathitanon, Nuttavut Sumransub, Pranisa Jamjuntra, Peti Thuwajit, and Marjorie De la Fuente performed the literature review and data analysis; Chanitra Thuwajit, Marcela A. Hermoso, Jarupa Soongsathitanon, Supaporn Yangngam, Marjorie De la Fuente, and Glauben Landskron contributed in writing—original draft preparation; Jarupa Soongsathitanon, Nuttavut Sumransub, and Marjorie De la Fuente contributed in writing—review and editing; Chanitra Thuwajit, Marcela A. Hermoso, Marjorie De la Fuente, and Glauben Landskron contributed in writing—critical revision.

References

- 1.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maajani K., Jalali A., Alipour S., Khodadost M., Tohidinik H. R., Yazdani K. The global and regional survival rate of women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2019;19(3):165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harbeck N., Penault-Llorca F., Cortes J., et al. Breast cancer. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019;5(1) doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna W. M., Parra-Herran C., Lu F. I., Slodkowska E., Rakovitch E., Nofech-Mozes S. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: an update for the pathologist in the era of individualized risk assessment and tailored therapies. Modern Pathology. 2019;32(7):896–915. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betts C. B., Pennock N. D., Caruso B. P., Ruffell B., Borges V. F., Schedin P. Mucosal immunity in the female murine mammary gland. Journal of Immunology. 2018;201(2):734–746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankaran V., Ikeda H., Bruce A. T., et al. IFNγ and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/35074122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edechi C. A., Ikeogu N., Uzonna J. E., Myal Y. Regulation of immunity in breast cancer. Cancers. 2019;11(8):p. 1080. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamarron B. F., Chen W. Dual roles of immune cells and their factors in cancer development and progression. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2011;7(5):651–658. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solinas C., Gombos A., Latifyan S., Piccart-Gebhart M., Kok M., Buisseret L. Targeting immune checkpoints in breast cancer: an update of early results. ESMO Open. 2017;2(5, article e000255) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo H., Tu G., Liu Z., Liu M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: a multifaceted driver of breast cancer progression. Cancer Letters. 2015;361(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchsbaum R. J., Oh S. Y. Breast cancer-associated fibroblasts: where we are and where we need to go. Cancers. 2016;8(2):p. 19. doi: 10.3390/cancers8020019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiao A., Gu F., Guo X., Zhang X., Fu L. Breast cancer-associated fibroblasts: their roles in tumor initiation, progression and clinical applications. Frontiers in Medicine. 2016;10(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/s11684-016-0431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung Y. Y., Kim H. M., Koo J. S. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in breast cancer pathobiology. Histology and Histopathology. 2016;31(4):371–378. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell M. I., Engelbrecht A. M. Metabolic hijacking: a survival strategy cancer cells exploit? Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2017;109:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sazeides C., Le A. Metabolic relationship between cancer-associated fibroblasts and cancer cells. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2018;1063:149–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-77736-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X., Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 2019;18(2):99–115. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houthuijzen J. M., Jonkers J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as key regulators of the breast cancer tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2018;37(4):577–597. doi: 10.1007/s10555-018-9768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao Y., Keller E. T., Garfield D. H., Shen K., Wang J. Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2013;32(1-2):303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martins D., Schmitt F. Microenvironment in breast tumorigenesis: friend or foe? Histology and Histopathology. 2019;34(1):13–24. doi: 10.14670/HH-18-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degnim A. C., Brahmbhatt R. D., Radisky D. C., et al. Immune cell quantitation in normal breast tissue lobules with and without lobulitis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2014;144(3):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2896-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degnim A. C., Hoskin T. L., Arshad M., et al. Alterations in the immune cell composition in premalignant breast tissue that precede breast cancer development. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017;23(14):3945–3952. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adhikary S., Hoskin T. L., Stallings-Mann M. L., et al. Cytotoxic T cell depletion with increasing epithelial abnormality in women with benign breast disease. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2020;180(1):55–61. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05493-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gil del Alcazar C. R., Huh S. J., Ekram M. B., et al. Immune escape in breast cancer during in situ to invasive carcinoma transition. Cancer Discovery. 2017;7(10):1098–1115. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loi S., Sirtaine N., Piette F., et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(7):860–867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams S., Gray R. J., Demaria S., et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(27):2959–2966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruffell B., Au A., Rugo H. S., Esserman L. J., Hwang E. S., Coussens L. M. Leukocyte composition of human breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(8):2796–2801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104303108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denkert C., Loibl S., Noske A., et al. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(1):105–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali H. R., Provenzano E., Dawson S. J., et al. Association between CD8+ T-cell infiltration and breast cancer survival in 12 439 patients. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25(8):1536–1543. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang H. W., Jung H., Hyeon J., et al. A nomogram to predict pathologic complete response (pCR) and the value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2019;173(2):255–266. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4981-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu B., Tse L. A., Wang D., et al. Immune gene expression profiling reveals heterogeneity in luminal breast tumors. Breast Cancer Research. 2019;21(1):p. 147. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1218-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emens L. A., Cruz C., Eder J. P., et al. Long-term clinical outcomes and biomarker analyses of atezolizumab therapy for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 1 study. JAMA Oncology. 2019;5(1):74–82. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nanda R., Chow L. Q., Dees E. C., et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced triple-negative breast cancer: phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(21):2460–2467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Planes-Laine G., Rochigneux P., Bertucci F., et al. PD-1/PD-L1 targeting in breast cancer: the first clinical evidences are emerging. A literature review. Cancers. 2019;11(7):p. 1033. doi: 10.3390/cancers11071033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L., Wang Y., Miao L., Liu Q., Musetti S., Li J., et al. Combination immunotherapy of MUC1 mRNA nano-vaccine and CTLA-4 blockade effectively inhibits growth of triple negative breast cancer. Molecular Therapy. 2018;26(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parra K., Valenzuela P., Lerma N., et al. Impact of CTLA-4 blockade in conjunction with metronomic chemotherapy on preclinical breast cancer growth. British Journal of Cancer. 2017;116(3):324–334. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayraktar S., Batoo S., Okuno S., Gluck S. Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Journal of Carcinogenesis. 2019;18(1):p. 2. doi: 10.4103/jcar.JCar_2_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koretzky G. A. Multiple roles of CD4 and CD8 in T cell activation. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(5):2643–2644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1090076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baxevanis C. N., Sofopoulos M., Fortis S. P., Perez S. A. The role of immune infiltrates as prognostic biomarkers in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2019;68(10):1671–1680. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farhood B., Najafi M., Mortezaee K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: a review. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(6):8509–8521. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong C. C., Yao S., McCann S. E., et al. Pretreatment levels of circulating Th1 and Th2 cytokines, and their ratios, are associated with ER-negative and triple negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;139(2):477–488. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2549-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu-Trantien C., Loi S., Garaud S., et al. CD4+ follicular helper T cell infiltration predicts breast cancer survival. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(7):2873–2892. doi: 10.1172/JCI67428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu S., Lin J., Qiao G., Wang X., Xu Y. Tim-3 identifies exhausted follicular helper T cells in breast cancer patients. Immunobiology. 2016;221(9):986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorvik K. B., Hammarström C., Fauskanger M., et al. Adoptive transfer of tumor-specific Th2 cells eradicates tumors by triggering an in situ inflammatory immune response. Cancer Research. 2016;76(23):6864–6876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fabre J., Giustiniani J., Garbar C., et al. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: the protumor effects of IL-17 related to cancer type. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(9):p. 1433. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du J., Xu K. Y., Fang L. Y., Qi X. L. Interleukin-17, produced by lymphocytes, promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of breast cancer. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2012;6(5):1099–1102. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin-Orozco N., Muranski P., Chung Y., et al. T helper 17 cells promote cytotoxic T cell activation in tumor immunity. Immunity. 2009;31(5):787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang L., Qi Y., Hu J., Tang L., Zhao S., Shan B. Expression of Th17 cells in breast cancer tissue and its association with clinical parameters. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2012;62(1):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y., Xu J., Su H., et al. Interleukin-17 is a favorable prognostic marker for colorectal cancer. Clinical & Translational Oncology. 2015;17(1):50–56. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lv L., Pan K., Li X. D., et al. The accumulation and prognosis value of tumor infiltrating IL-17 producing cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6(3, article e18219) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asadzadeh Z., Mohammadi H., Safarzadeh E., et al. The paradox of Th17 cell functions in tumor immunity. Cellular Immunology. 2017;322:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su X., Ye J., Hsueh E. C., Zhang Y., Hoft D. F., Peng G. Tumor microenvironments direct the recruitment and expansion of human Th17 cells. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(3):1630–1641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benevides L., Cardoso C. R., Tiezzi D. G., Marana H. R., Andrade J. M., Silva J. S. Enrichment of regulatory T cells in invasive breast tumor correlates with the upregulation of IL-17A expression and invasiveness of the tumor. European Journal of Immunology. 2013;43(6):1518–1528. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen W. C., Lai Y. H., Chen H. Y., Guo H. R., Su I. J., Chen H. H. Interleukin-17-producing cell infiltration in the breast cancer tumour microenvironment is a poor prognostic factor. Histopathology. 2013;63(2):225–233. doi: 10.1111/his.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cochaud S., Giustiniani J., Thomas C., et al. IL-17A is produced by breast cancer TILs and promotes chemoresistance and proliferation through ERK1/2. Scientific Reports. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1038/srep03456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung A. S., Wu X., Zhuang G., et al. An interleukin-17-mediated paracrine network promotes tumor resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nature Medicine. 2013;19(9):1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/nm.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alinejad V., Dolati S., Motallebnezhad M., Yousefi M. The role of IL17B-IL17RB signaling pathway in breast cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017;88:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laprevotte E., Cochaud S., du Manoir S., et al. The IL-17B-IL-17 receptor B pathway promotes resistance to paclitaxel in breast tumors through activation of the ERK1/2 pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(69):113360–113372. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang C. K., Yang C. Y., Jeng Y. M., et al. Autocrine/paracrine mechanism of interleukin-17B receptor promotes breast tumorigenesis through NF-κB-mediated antiapoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 2014;33(23):2968–2977. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alinejad V., Hossein Somi M., Baradaran B., et al. Co-delivery of IL17RB siRNA and doxorubicin by chitosan-based nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer efficacy in breast cancer cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2016;83:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhary B., Elkord E. Regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment and cancer progression: role and therapeutic targeting. Vaccines. 2016;4(3):p. 28. doi: 10.3390/vaccines4030028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Najafi M., Farhood B., Mortezaee K. Contribution of regulatory T cells to cancer: a review. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(6):7983–7993. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta S., Joshi K., Wig J. D., Arora S. K. Intratumoral FOXP3 expression in infiltrating breast carcinoma: its association with clinicopathologic parameters and angiogenesis. Acta Oncologica. 2007;46(6):792–797. doi: 10.1080/02841860701233443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ladoire S., Mignot G., Dabakuyo S., et al. In situ immune response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer predicts survival. The Journal of Pathology. 2011;224(3):389–400. doi: 10.1002/path.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J. Q., Li X. Y., Yu H. Q., et al. Retracted article: Tumor-specific Th2 responses inhibit growth of CT26 colon-cancer cells in mice via converting intratumor regulatory T cells to Th9 cells. Scientific Reports. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1038/srep10665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Park J., Li H., Zhang M., et al. Murine Th9 cells promote the survival of myeloid dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2014;63(8):835–845. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1557-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen M., Wang J., Ren X. New insights into tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes in breast cancer: clinical impacts and regulatory mechanisms. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018;9:p. 470. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Engblom C., Pfirschke C., Pittet M. J. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2016;16(7):447–462. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmid M. C., Varner J. A. Myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment: modulation of tumor angiogenesis and tumor inflammation. Journal of Oncology. 2010;2010:10. doi: 10.1155/2010/201026.201026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez-Garcia B., Eiro N., Miranda M. A., et al. Prognostic significance of inflammatory factors expression by stroma from breast carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37(8):768–776. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Choi J., Gyamfi J., Jang H., Koo J. S. The role of tumor-associated macrophage in breast cancer biology. Histology and Histopathology. 2018;33(2):133–145. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Villadangos J. A., Young L. Antigen-presentation properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity. 2008;29(3):352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Böttcher J. P., Reis e Sousa C. The role of type 1 conventional dendritic cells in cancer immunity. Trends in Cancer. 2018;4(11):784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hubert M., Gobbini E., Couillault C., et al. IFN-III is selectively produced by cDC1 and predicts good clinical outcome in breast cancer. Science Immunology. 2020;5(46, article eaav3942) doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee H., Lee H. J., Song I. H., et al. CD11c-positive dendritic cells in triple-negative breast cancer. In Vivo. 2018;32(6):1561–1569. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Michea P., Noël F., Zakine E., et al. Adjustment of dendritic cells to the breast-cancer microenvironment is subset specific. Nature Immunology. 2018;19(8):885–897. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gadalla R., Hassan H., Ibrahim S. A., et al. Tumor microenvironmental plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to breast cancer lymph node metastasis via CXCR4/SDF-1 axis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2019;174(3):679–691. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.da Cunha A., Michelin M. A., Murta E. F. Pattern response of dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(3):495–502. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Q., Zhang C., Sun A., Zheng Y., Wang L., Cao X. Tumor-educated CD11bhighIalow regulatory dendritic cells suppress T cell response through arginase I. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(10):6207–6216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aspord C., Pedroza-Gonzalez A., Gallegos M., et al. Breast cancer instructs dendritic cells to prime interleukin 13-secreting CD4+ T cells that facilitate tumor development. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(5):1037–1047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de Azevedo-Santos A. P. S., Rocha M. C. B., Guimarães S. J. A., et al. Could increased expression of Hsp27, an “anti-inflammatory” chaperone, contribute to the monocyte-derived dendritic cell bias towards tolerance induction in breast cancer patients? Mediators of Inflammation. 2019;2019:9. doi: 10.1155/2019/8346930.8346930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gabrilovich D. I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunology Research. 2017;5(1):3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Markowitz J., Wesolowski R., Papenfuss T., Brooks T. R., Carson W. E., 3rd. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;140(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pastaki Khoshbin A., Eskian M., Keshavarz-Fathi M., Rezaei N. Roles of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer metastasis: immunosuppression and beyond. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis (Warsz) 2019;67(2):89–102. doi: 10.1007/s00005-018-0531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Law A. M. K., Valdes-Mora F., Gallego-Ortega D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cells. 2020;9(3):p. 561. doi: 10.3390/cells9030561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trikha P., Carson W. E., 3rd. Signaling pathways involved in MDSC regulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1846(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bruger A. M., Dorhoi A., Esendagli G., et al. How to measure the immunosuppressive activity of MDSC: assays, problems and potential solutions. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2019;68(4):631–644. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ma X., Wang M., Yin T., Zhao Y., Wei X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote metastasis in breast cancer after the stress of operative removal of the primary cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2019;9:p. 855. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Diaz-Montero C. M., Salem M. L., Nishimura M. I., Garrett-Mayer E., Cole D. J., Montero A. J. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2009;58(1):49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bergenfelz C., Larsson A. M., von Stedingk K., et al. Systemic monocytic-MDSCs are generated from monocytes and correlate with disease progression in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Varricchi G., de Paulis A., Marone G., Galli S. J. Future needs in mast cell biology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(18):p. 4397. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Varricchi G., Galdiero M. R., Loffredo S., et al. Are mast cells MASTers in cancer? Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8:p. 424. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dabbous M. K., Walker R., Haney L., Carter L. M., Nicolson G. L., Woolley D. E. Mast cells and matrix degradation at sites of tumour invasion in rat mammary adenocarcinoma. British Journal of Cancer. 1986;54(3):459–465. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1986.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Komi D. E. A., Redegeld F. A. Role of mast cells in shaping the tumor microenvironment. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2020;58(3):313–325. doi: 10.1007/s12016-019-08753-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aponte-Lopez A., Fuentes-Panana E. M., Cortes-Munoz D., Munoz-Cruz S. Mast cell, the neglected member of the tumor microenvironment: role in breast cancer. Journal of Immunology Research. 2018;2018:11. doi: 10.1155/2018/2584243.2584243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Theoharides T. C., Conti P. Mast cells: the Jekyll and Hyde of tumor growth. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25(5):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dalton D. K., Noelle R. J. The roles of mast cells in anticancer immunity. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2012;61(9):1511–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mangia A., Malfettone A., Rossi R., et al. Tissue remodelling in breast cancer: human mast cell tryptase as an initiator of myofibroblast differentiation. Histopathology. 2011;58(7):1096–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carpenco E., Ceauşu R. A., Cimpean A. M., et al. Mast cells as an indicator and prognostic marker in molecular subtypes of breast cancer. In Vivo. 2019;33(3):743–748. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cimpean A. M., Tamma R., Ruggieri S., Nico B., Toma A., Ribatti D. Mast cells in breast cancer angiogenesis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2017;115:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Souza D. A., Toso V. D., Campos M. R. C., Lara V. S., Oliver C., Jamur M. C. Expression of mast cell proteases correlates with mast cell maturation and angiogenesis during tumor progression. PLoS One. 2012;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Glajcar A., Szpor J., Pacek A., et al. The relationship between breast cancer molecular subtypes and mast cell populations in tumor microenvironment. Virchows Archiv. 2017;470(5):505–515. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Konjevic G., Jurisic V., Jovic V., et al. Investigation of NK cell function and their modulation in different malignancies. Immunologic Research. 2012;52(1-2):139–156. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Crome S. Q., Lang P. A., Lang K. S., Ohashi P. S. Natural killer cells regulate diverse T cell responses. Trends in Immunology. 2013;34(7):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Muntasell A., Cabo M., Servitja S., et al. Interplay between natural killer cells and anti-HER2 antibodies: perspectives for breast cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8:p. 1544. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Abouelghar A., Hasnah R., Taouk G., Saad M., Karam M. Prognostic values of the mRNA expression of natural killer receptor ligands and their association with clinicopathological features in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9(43):27171–27196. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nair N., Calle A. S., Zahra M. H., et al. A cancer stem cell model as the point of origin of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 6838. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vastrad B., Vastrad C., Tengli A., Iliger S. Identification of differentially expressed genes regulated by molecular signature in breast cancer-associated fibroblasts by bioinformatics analysis. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2018;297(1):161–183. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4562-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Costa A., Kieffer Y., Scholer-Dahirel A., et al. Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(3):463–479.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.011. e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hu G., Xu F., Zhong K., Wang S., Huang L., Chen W. Activated tumor-infiltrating fibroblasts predict worse prognosis in breast cancer patients. Journal of Cancer. 2018;9(20):3736–3742. doi: 10.7150/jca.28054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Amornsupak K., Jamjuntra P., Warnnissorn M., et al. High ASMA+ fibroblasts and low cytoplasmic HMGB1+ breast cancer cells predict poor prognosis. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2017;17(6):441–452.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang Z., Ni W., Cui C., Fang L., Xuan Y. Tenascin C is a prognostic determinant and potential cancer-associated fibroblasts marker for breast ductal carcinoma. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2017;102(2):262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Su S., Chen J., Yao H., et al. CD10+GPR77+ cancer-associated fibroblasts promote cancer formation and chemoresistance by sustaining cancer stemness. Cell. 2018;172(4):841–856.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liu Y., Yu C., Wu Y., et al. CD44+fibroblasts increases breast cancer cell survival and drug resistanceviaIGF2BP3-CD44-IGF2 signalling. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2017;21(9):1979–1988. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Paulsson J., Rydén L., Strell C., et al. High expression of stromal PDGFRβ is associated with reduced benefit of tamoxifen in breast cancer. The Journal of Pathology. Clinical Research. 2017;3(1):38–43. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Miyake Y., Hirokawa M., Norimatsu Y., et al. Mucinous breast carcinoma with myoepithelial-like spindle cells. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2009;37(6):393–396. doi: 10.1002/dc.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Catteau X., Simon P., Buxant F., Noel J. C. Expression of the glucocorticoid receptor in breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2016;5(4):372–376. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Boesch M., onder L., Cheng H. W., et al. Interleukin 7-expressing fibroblasts promote breast cancer growth through sustenance of tumor cell stemness. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(4, article e1414129) doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1414129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kikuchi K., McNamara K. M., Miki Y., et al. Effects of cytokines derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts on androgen synthetic enzymes in estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2017;166(3):709–723. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ratajczak-Wielgomas K., Grzegrzolka J., Piotrowska A., Gomulkiewicz A., Witkiewicz W., Dziegiel P. Periostin expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts of invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Oncology Reports. 2016;36(5):2745–2754. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen Z., Yan X., Li K., Ling Y., Kang H. Stromal fibroblast-derived MFAP5 promotes the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells via Notch1/slug signaling. Clinical & Translational Oncology. 2020;22(4):522–531. doi: 10.1007/s12094-019-02156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wu Y., Wu P., Zhang Q., Chen W., Liu X., Zheng W. MFAP5 promotes basal-like breast cancer progression by activating the EMT program. Cell & Bioscience. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liubomirski Y., Lerrer S., Meshel T., et al. Notch-mediated tumor-stroma-inflammation networks promote invasive properties and CXCL8 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10:p. 804. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liubomirski Y., Lerrer S., Meshel T., et al. Tumor-stroma-inflammation networks promote pro-metastatic chemokines and aggressiveness characteristics in triple-negative breast cancer. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10:p. 757. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Eiro N., Gonzalez L. O., Fraile M., Cid S., Schneider J., Vizoso F. J. Breast cancer tumor stroma: cellular components, phenotypic heterogeneity, intercellular communication, prognostic implications and therapeutic opportunities. Cancers. 2019;11(5):p. 664. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cid S., Eiro N., Fernández B., et al. Prognostic influence of tumor stroma on breast cancer subtypes. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2018;18(1):e123–e133. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zou A., Lambert D., Yeh H., et al. Elevated CXCL1 expression in breast cancer stroma predicts poor prognosis and is inversely associated with expression of TGF-β signaling proteins. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wen S., Hou Y., Fu L., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-derived IL32 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis via integrin β3-p38 MAPK signalling. Cancer Letters. 2019;442:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ray A., Nkhata K. J., Cleary M. P. Effects of leptin on human breast cancer cell lines in relationship to estrogen receptor and HER2 status. International Journal of Oncology. 2007;30(6):1499–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Andò S., Barone I., Giordano C., Bonofiglio D., Catalano S. The multifaceted mechanism of leptin signaling within tumor microenvironment in driving breast cancer growth and progression. Frontiers in Oncology. 2014;4:p. 340. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yan Y., Chen X., Wang X., et al. The effects and the mechanisms of autophagy on the cancer-associated fibroblasts in cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;38(1):p. 171. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhao X. L., Lin Y., Jiang J., et al. High-mobility group box 1 released by autophagic cancer-associated fibroblasts maintains the stemness of luminal breast cancer cells. The Journal of Pathology. 2017;243(3):376–389. doi: 10.1002/path.4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang M., Zhang J., Huang Y., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts autophagy enhances progression of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Medical Science Monitor. 2017;23:3904–3912. doi: 10.12659/msm.902870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Amornsupak K., Insawang T., Thuwajit P., O-Charoenrat P., Eccles S. A., Thuwajit C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce high mobility group box 1 and contribute to resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):p. 955. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mussunoor S., Murray G. I. The role of annexins in tumour development and progression. The Journal of Pathology. 2008;216(2):131–140. doi: 10.1002/path.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Geary L. A., Nash K. A., Adisetiyo H., et al. CAF-secreted annexin A1 induces prostate cancer cells to gain stem cell-like features. Molecular Cancer Research. 2014;12(4):607–621. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]