Dear Editor:

On 7 January 2021, the Spanish Navy’s Health Services Directorate for Bahía de Cádiz, in Rota, started the first COVID-19 vaccination campaign for navy personnel. We administered the Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, officially approved by the European Medicines Agency on 21 December 2020. Commercialisation of the Moderna vaccine was subsequently approved on 6 January 2021; this vaccine has a very similar action mechanism to that of the Pfizer vaccine, using mRNA.1

Both vaccines are associated with adverse reactions involving the orofacial region (one case in 1000 vaccinated individuals), such as Bell’s palsy; however, this observation was not included in information targeted at patients in the United States and Canada.2

A literature search confirmed that rare cases of Bell’s palsy were observed in the phase 3 trial of the BNT162b2 vaccine, with 4 cases among patients receiving the vaccine and none in the placebo group. However, as incidence did not exceed that observed in the general population, no clear association was established between vaccination and Bell’s palsy.3

Between 7 January and 18 March 2021, our department administered a total of 1757 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine, fully vaccinating 877 individuals with both doses. Three different batches of the vaccine were used.

We present the case of a patient who developed Bell’s palsy several days after being vaccinated against COVID-19. The patient consented to the publication of the personal information included in this article.

The patient was a 50-year-old white man with no relevant medical history, who received the first dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine on 9 February 2021. He reported local pain at the injection site on the second and third days after inoculation, and general fatigue on days 4 and 5; these are common adverse effects of the vaccine.4

On 28 February, 9 days after administration of the first dose, he noticed muscle weakness on the left side of the face, preventing him from drinking fluids, and visited the emergency department at Hospital General de Puerto Real (Cádiz). He presented facial droop, effacement of the nasolabial fold, and flaccidity on the left side of the face. Physical examination revealed complete paralysis of the left side of the face (the patient was unable to raise his eyebrow, close his left eye, or lift the labial commissure); he also presented effacement of frontal wrinkles.

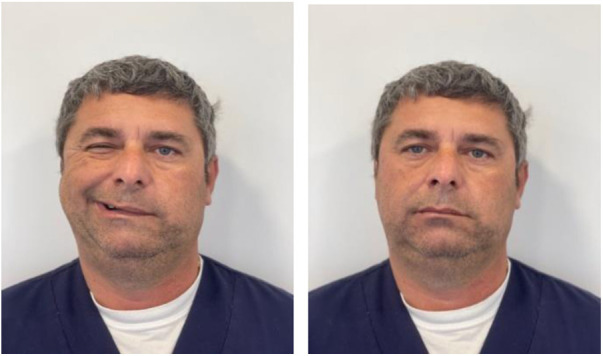

The emergency department diagnosed the patient with facial palsy and referred him to the outpatient neurology department (Fig. 1 ).

Figure 1.

Bell’s palsy in our patient.

The patient had no history of trauma or systemic infection, and presented no skin eruptions compatible with herpes zoster infection or cutaneous abnormalities compatible with skin cancer. He also had not suffered a tick bite.

A brain MRI study (axial, sagittal, and coronal planes; T1- and T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences) ruled out intracranial space-occupying lesions and ischaemic events.

The patient had no history of previous or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The neurology department confirmed the diagnosis of acute unilateral Bell’s palsy.

The patient was treated with prednisone at 60 mg/day for 7 days, which was subsequently tapered to 30 mg/day for 7 days and 15 mg/day for the next 7 days, with a total of 21 days of treatment.

He was instructed to protect and lubricate the eye with artificial tears during the day and an eye patch at night. Water-soluble B-complex vitamins were subsequently added to accelerate recovery of the affected nerve.

At 21 days, after completing the course of corticotherapy, paresis began to improve, although the patient continued to have difficulty fully closing the eye and raising the labial commissure; this progression is compatible with the course of the disease.5

In accordance with the summary of product characteristics for the Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19, published by the Spanish Ministry of Health, the patient did not receive a second dose due to the severe adverse reaction.6

The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is fundamentally established by exclusion, based on clinical symptoms, and cannot be confirmed by any specific laboratory test. It is characterised by rapidly progressive (less than 72 hours), unilateral, and generally self-limited symptoms that resolve within 3-6 months in 80% of cases.7 Its aetiology is uncertain and it may be triggered by numerous causes.8

While we are unable to demonstrate that Bell’s palsy was an adverse reaction to the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine in our patient, an increasing body of evidence obliges us to reflect on the close relationship between both events.

Colella et al.9 report a case of Bell’s palsy with similar characteristics to our own case in a patient who had received the same vaccine.

Therefore, we consider that it would be beneficial for the healthcare authorities to emphasise the importance of monitoring patients developing Bell’s palsy after the administration of mRNA vaccines.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Gómez de Terreros Caro G, Gil Díaz S, Pérez Alé M, Martínez Gimeno ML. Parálisis de Bell tras vacunación COVID-19: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2021;36:567–568.

References

- 1.Picazo J.J. Sociedad Española de Quimioterapia: infección y vacunas; Madrid: 2021. Vacuna frente al COVID-19. Versión 4.4; pp. 2–25. Available from: https://seq.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/vacunas-covid-4.4.pdf. [Accessed 2 March 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cirillo N. Reported orofacial adverse effects of COVID‐19 vaccines: the knowns and the unknowns. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1111/jop.13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards K.M., Orenstein W.A. UpToDate; Waltham (MA): 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández S., López Lizano G. Parálisis de Bell: diagnóstico ytratamiento. Ciencia y Salud. 2021;5:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consejo Interterritorial, Sistema Nacional de Salud. COMIRNATY (Vacuna COVID-19 ARNm, Pfizer-BioNTech). Available from: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/covid19/docs/Guia_Tecnica_COMIRNATY.pdf. [Accessed 2 March 2021].

- 7.Rozman C., Cardellach F. 19th ed. Elsevier; Barcelona: 2020. Farreras Rozman. Medicina Interna; pp. 1473–1474. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baugh R.F., Basura G.J., Ishii L.E., Schwartz S.R., Drumheller C.M., Burkholder R. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2013;149(3 Suppl):S1–27. doi: 10.1177/0194599813505967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colella G., Orlandi M., Cirillo N. Bell’s palsy following COVID-19 vaccination. J Neurol. 2021:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]