Abstract

Objectives

Given the ongoing pandemic emergency, there is a need to identify SARS CoV-2 infection in various community settings. Rapid antigen testing is spreading worldwide, but diagnostic accuracy is extremely variable. Our study compared a microfluidic rapid antigen test with a reference molecular assay in patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) of a general hospital from October 2020 to January 2021.

Methods

Nasopharyngeal swabs collected in patients with suspected COVID-19 and in patients with no symptoms suggesting COVID-19, but requiring hospitalization, were obtained.

Results

792 patients of median age 71 years were included. With a prevalence of 21%, the results showed: 68.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 60.9–75.5) sensitivity; 95.2% (95% CI: 93.1–96.7) specificity; 79.2% (95% CI: 71.4–85.3) positive predictive value (PPV); 91.9% (95% CI: 89.5–93.9) negative predictive value; 3.8 (95% CI: 2.7–5.3) positive likelihood ratio (LR+); and 0.09 (95% CI: 0.07–0.1) negative likelihood ratio (LR−). In the symptomatic subgroup, sensitivity increased to 81% (95% CI: 70.3–88.6) and PPV to 96.9% (95% CI: 88.5–99.5), along with an LR+ of 32 (95% CI: 8.2–125.4).

Conclusions

The new rapid antigen test showed an overall excellent diagnostic performance in a challenging situation, such as that of an ED during the COVID-19 emergency.

Keywords (MeSH): Diagnostic techniques and procedures, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Microfluidic analytical techniques, Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, Emergency department

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus with four main structural proteins: spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid (Naqvi et al., 2020). It is a member of the human coronavirus family (HCoV), of which six were already known to cause disease (Yin and Wunderink, 2018). Among these, four are known as human endemic coronaviruses: HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1, causing acute self-limiting common-cold symptoms (Yin and Wunderink, 2018). The other two — SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV — cause outbreaks of severe lower respiratory tract infection (Drosten et al., 2003; Zaki et al., 2012).

The symptoms of COVID-19 patients are quite variable, ranging from asymptomatic cases to flu-like symptoms (fever, dry cough, dyspnea, fatigue), and up to cases of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by bilateral interstitial pneumonia and requiring admission to an intensive care unit (Hassan et al., 2020; Sheleme et al., 2020).

For these reasons, laboratory support is essential for a correct diagnosis of COVID-19, with the gold standard being RNA detection of SARS-CoV-2 by means of molecular methods (Cheng et al., 2020; Loeffelholz and Tang, 2020). Nevertheless, molecular testing is expensive, time consuming, and requires adequately skilled staff, while it can take several hours to obtain a result. On the other hand, rapid antigen testing for detection of SARS-CoV-2 is spreading worldwide, allowing a quick diagnosis in many different community settings; however, diagnostic accuracy is extremely variable, with sensitivity ranging from 0% to 94% (Dinnes et al., 2021). The aim of this study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of a new rapid antigen test based on microfluidic technology with a reference molecular assay in a population of patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) of a general hospital.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective observational study including all nasopharyngeal swabs collected for diagnostic purposes from patients aged ≥ 18 years admitted to the ED of the SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo Hospital of Alessandria, Italy, from October 2020 to January 2021. All patients included in the study were evaluated by the ED physician, who took medical histories and performed physical examinations. The symptoms considered as associated with possible COVID-19 were those already described by other authors (Siordia, 2020). Nasopharyngeal swab sampling was performed in patients with suspected COVID-19 and in patients without symptoms suggesting COVID-19, but requiring hospitalization. This was because up to 45% of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 can be asymptomatic (Oran and Topol, 2020), while IDSA's COVID-19 diagnostic guidelines (Hanson et al., 2020) suggest direct SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing in asymptomatic individuals with no known contact with COVID-19 who are being hospitalized in areas with a high prevalence of COVID-19 in the community. Two concurrent swabs were collected from all patients — one nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and one nasal swab for rapid antigen testing.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected by means of Universal Transport Medium for Viruses, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma (Copan UTM® system; Copan, Italy). SARS-CoV-2 detection was performed using the Alinity m SARS-CoV-2 AMP kit (Alinity m SARS-COV-2 assay, 2021) run on the Abbott Alinity m system (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA). Both kit and instrumentation were employed according to the manufacturer's instructions for both the handling and interpretation of the results. The assay is a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for the qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in nasal, nasopharyngeal, or oropharyngeal swabs, and in bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. The system employs magnetic microparticle technology to capture, wash, and elute the nucleic acid. An internal control is introduced into each specimen at the beginning of the sample preparation, and both a positive control and a negative control are processed concurrently. After disruption of SARS-CoV-2 virions by guanidine isothiocyanate, nucleic acids are captured on the magnetic microparticles, and inhibitors and unbound sample components are removed by subsequent washing steps. The purified RNA is then combined with liquid unit-dose Alinity m SARS-CoV-2 activation reagent and liquid unit-dose Alinity m SARS-CoV-2. During the amplification step, the target RNA is converted to cDNA by the reverse transcriptase. The target sequences for the assay are in the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, which are highly conserved and specific. Amplification of the three targets (SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, SARS-CoV-2 N, and internal control) takes place simultaneously in the same reaction amplification/detection reagents. If the target sequences are present in the sample, the hybridization with complementary sequences separates the fluorophore and the quencher, allowing fluorescent emission and detection. The lowest concentration level with observed positive rates ≥ 95% is 100 virus copies/ml, and the maximum number of amplification cycles is 45.

SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection

The nucleocapsid protein antigen of SARS-CoV-2 was detected using the LumiraDx SARS-CoV-2 Ag test (Technical validation for LumiraDx SARS-CoV-2 Ag test, 2021), a rapid microfluidic immunofluorescence assay for use with the LumiraDx platform for the qualitative detection of nucleocapsid protein antigen to SARS-CoV-2 directly from nasal swab samples. Each sample was collected by means of a standard dry swab eluted into a vial containing extraction buffer. Using a vial dropper cap, a single drop of the sample in the extraction buffer was added to the test strip containing dried reagents. The test result was determined from the amount of fluorescence detected by the device within 12 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR−) —with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) — and agreement by Cohen's kappa between the antigen test results and the RT-PCR results were calculated as described by Eusebi et al. (2013). The median values of threshold cycles (CTs) were also calculated and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The SPSS statistical package version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Descriptive

In total, 792 patients were included in the study. The median age was 71 years (IQR: 53–82.7) and 50.9% (403/792) were males. 52.4% (415/792) had one or more symptoms associated with possible COVID-19. The patients’ clinical characteristics are described in Table 1 . For the 792 swabs performed, 144 (18.2%) were positive according to the antigen test, compared with 166 (21%) for the molecular test (corresponding with the prevalence of disease in the whole study population). The 166 patients for whom nasopharyngeal swabs were positive according to the molecular method had a median age of 72 years (IQR: 55–84.3) and 91/166 (54.8%) were males.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the whole population (n = 792)

| Sign/symptom | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 377 (47.6) |

| Symptomatic | 415 (52.4) |

| Body temperature ≥ 37.5°C | 71 (9) |

| Cough | 51 (6.4) |

| Dyspnea | 141 (17.8) |

| Headache | 36 (4.5) |

| Pharyngodynia | 3 (0.4) |

| Asthenia | 38 (4.8) |

| Myalgia | 16 (2) |

| Rhinorrhea | 1 (0.1) |

| Chest pain | 73 (9.2) |

| Abdominal pain | 96 (12.1) |

| Nausea | 43 (5.4) |

| Expectoration | 1 (0.1) |

| Diarrhea | 25 (3.2) |

| Fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea | 207 (26.1) |

Diagnostic accuracy in the whole population

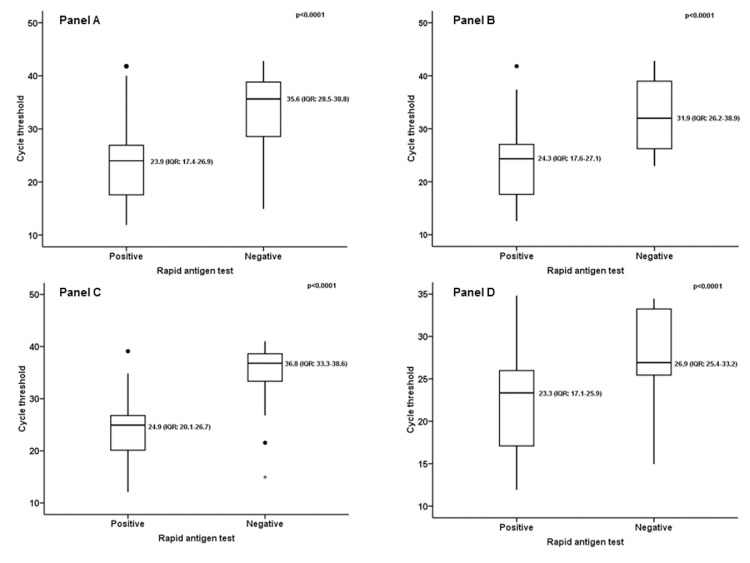

The comparison between the two tests in the whole population is described in Table 2 . With a prevalence of disease of 21% (166/792), the results showed: 68.7% (95% CI: 60.9–75.5) sensitivity; 95.2% (95% CI: 93.1–96.7) specificity; 79.2% (95% CI: 71.4–85.3) PPV; 91.9% (95% CI: 89.5–93.9) NPV; 3.8 (95% CI: 2.7–5.3) LR+; and 0.09 (95% CI: 0.07–0.1) LR−. The agreement measured by Cohen's kappa was 0.672 (p < 0.0001) — substantial. Considering only the swabs positive according to the molecular test (166/792) and the relative CTs, and comparing the median CT value for the molecular swabs corresponding with the 114/166 (68.7%) antigen-positive results with that for the molecular swabs corresponding with the 52/166 (31.3%) antigen-negative results, a significant difference was found (Figure 1 A). The median CT value for corresponding antigen-positive results was 23.9 (IQR: 17.4–26.9); the median CT value for corresponding antigen-negative results was 35.6 (IQR: 28.5–38.8); p < 0.0001.

Table 2.

Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen test with that of RT-PCR

| Rapid antigen test results | RT-PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Total (%) | |

| Whole population (n = 792) | |||

| Positive | 114 (14.4) | 30 (3.8) | 144 (18.2) |

| Negative | 52 (6.6) | 596 (75.2) | 648 (81.8) |

| Total | 166 (21) | 626 (79) | 792 (100) |

| Fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea (n = 207) | |||

| Positive | 64 (30.9) | 2 (0.9) | 66 (31.9) |

| Negative | 15 (7.2) | 126 (61) | 141 (68.1) |

| Total | 79 (38.2) | 128 (61.8) | 207 (100) |

| Asymptomatic (n = 377) | |||

| Positive | 26 (6.9) | 20 (5.3) | 46 (12.2) |

| Negative | 28 (7.4) | 303 (80.4) | 331 (87.8) |

| Total | 54 (14.3) | 323 (85.7) | 377 (100) |

| CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples (n = 792) | |||

| Positive | 107 (13.5) | 37 (4.7) | 144 (18.2) |

| Negative | 25 (3.2) | 623 (78.6) | 648 (81.8) |

| Total | 132 (16.7) | 660 (83.3) | 792 (100) |

| Only CTs ≥ 35 (n = 660) | |||

| Positive | 7 (1.1) | 30 (4.5) | 37 (5.6) |

| Negative | 27 (4.1) | 596 (90.3) | 623 (94.4) |

| Total | 34 (5.2) | 626 (94.8) | 660 (100) |

| Rapid antigen test performance | % | 95% CI | |

| Whole population (n = 792) | |||

| Sensitivity | 68.7 | 60.9–75.5 | |

| Specificity | 95.2 | 93.1–96.7 | |

| PPV | 79.2 | 71.4–85.3 | |

| NPV | 91.9 | 89.5–93.9 | |

| Fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea (n = 207) | |||

| Sensitivity | 81 | 70.3–88.6 | |

| Specificity | 98.4 | 93.9–99.7 | |

| PPV | 96.9 | 88.5–99.5 | |

| NPV | 89.4 | 82.7–93.7 | |

| Asymptomatic (n = 377) | |||

| Sensitivity | 48.1 | 34.5–62 | |

| Specificity | 93.8 | 90.4–96.1 | |

| PPV | 56.5 | 41.2–70.7 | |

| NPV | 91.5 | 87.8–94.2 | |

| CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples (n = 792) | |||

| Sensitivity | 81 | 73.1–87.1 | |

| Specificity | 94.4 | 92.3–95.9 | |

| PPV | 74.3 | 66.2–81 | |

| NPV | 96.1 | 94.3–97.4 | |

| Only CTs ≥ 35 (n = 660) | |||

| Sensitivity | 20.6 | 9.3–38.4 | |

| Specificity | 95.2 | 93.1–96.7 | |

| PPV | 18.9 | 8.5–35.7 | |

| NPV | 95.6 | 93.7–97.1 |

Data are shown as absolute numbers and percentage (%); RT-PCR: real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; CI: confidence interval; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; CTs: cycle thresholds

Figure 1.

(A) Comparison of median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 114/166 (68.7%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 52/166 (31.3%) antigen-negative results in the whole population. (B) Comparison of median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 64/79 (81%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 15/79 (19%) antigen-negative results, in patients with fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea. (C) Comparison of median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 26/54 (48.1%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 28/54 (51.9%) antigen-negative results, in asymptomatic patients. (D) Comparison of median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 107/132 (81%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 25/132 (19%) antigen-negative results, considering positive molecular swabs corresponding with CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples.

Diagnostic accuracy in symptomatic patients

Repeating the same analysis considering only the subgroup of patients who had at least one of the three main symptoms potentially associated with COVID-19 (fever, cough, and dyspnea) at the time of evaluation in the ED, involved 207/792 (26.1%) patients. The results of the comparison are described in Table 2. With a disease prevalence of 38.2% (79/207), the results showed: 81% (95% CI: 70.3–88.6) sensitivity; 98.4% (95% CI: 93.9–99.7) specificity; 96.9% (95% CI: 88.5–99.5) PPV; 89.4% (95% CI: 82.7–93.7) NPV; 32 (95% CI: 8.2–125.4) LR+; and 0.1 (95% CI: 0.07–0.2) LR−. Agreement calculated by Cohen's kappa was 0.820 (p < 0.0001) — almost perfect. Considering only the swabs that tested positive according to the molecular test in symptomatic subjects (79/207) and the relative CTs, and comparing the median CT value for the molecular swabs corresponding with the 64/79 (81%) antigen-positive results with that for the molecular swabs corresponding with the 15/79 (19%) antigen-negative results, a significant difference was found (Figure 1B). The median CT value for corresponding antigen-positive results was 24.3 (IQR: 17.6–27.1); the median CT value for corresponding antigen-negative results was 31.9 (IQR: 26.2–38.9); p < 0.0001.

Diagnostic accuracy in asymptomatic patients

The same analysis performed only on the subgroup of patients without any of the symptoms potentially associated with COVID-19 described in Table 1 at the time of evaluation in the ED is described in Table 2; 377 patients were considered. In this subgroup, the prevalence of disease was 14.3% (54/377) and the diagnostic accuracy was as follows: 48.1% (95% CI: 34.5–62) sensitivity; 93.8% (95% CI: 90.4–96.1) specificity; 56.5% (95% CI: 41.2–70.7) PPV; 91.5% (95% CI: 87.8–94.2) NPV; 1.3 (95% CI: 0.8–1.9) LR+; 0.09 (95% CI: 0.06–0.1) LR−. Agreement measured by Cohen's kappa was 0.447 (p < 0.0001) — moderate. Considering only the swabs that tested positive according to the molecular test in asymptomatic subjects (54/377), and comparing the median CT for molecular swabs corresponding with the 26/54 (48.1%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 28/54 (51.9%) antigen-negative results, a significant difference was found (Figure 1C): The median CT value for corresponding antigen-positive results was 24.9 (IQR: 20.1–26.7); the median CT value for corresponding antigen-negative results was 36.8 (IQR: 33.3–38.6); p < 0.0001.

Diagnostic accuracy considering positive molecular swabs with cycle thresholds ≥ 35 as low viral load samples

Considering the positive molecular swabs corresponding to CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples, the number of positive molecular swabs dropped from 166 to 132. The results of the comparison of diagnostic accuracy are described in Table 2. In this subgroup, the prevalence of disease was 16.6% (132/792) and the diagnostic accuracy was as follows: 81% (95% CI: 73.1–87.1) sensitivity; 94.4% (95% CI: 92.3–95.9) specificity; 74.3% (95% CI: 66.2–81) PPV; 96.1% (95% CI: 94.3–97.4) NPV; 2.9 (95% CI: 2.2–3.9) LR+; 0.04 (95% CI: 0.03–0.06) LR−. Agreement measured by Cohen's kappa was 0.728 (p < 0.0001) — substantial. As above, comparing the median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 107/132 (81%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 25/132 (19%) antigen-negative results, a significant difference was found (Figure 1D) — positive: 23.3 (IQR: 17.1–25.9) vs negative 26.9 (IQR: 25.4–33.2); p < 0.0001.

Diagnostic accuracy considering as positive only molecular swabs with cycle thresholds ≥ 35

Performing a comparative analysis including negative samples and only positive samples with CTs ≥ 35 showed a prevalence of 5.2% (34/660), with the diagnostic accuracy (Table 2) as follows: 20.6% (95% CI: 9.3–38.4) sensitivity; 95.2% (95% CI: 93.1–96.7) specificity; 18.9% (95% CI: 8.5–35.7) PPV; 95.6% (95% CI: 93.7–97.1) NPV; 0.2 (95% CI: 0.1–0.5) LR+; 0.05 (95% CI: 0.03–0.07) LR−. Agreement measured by Cohen's kappa was 0.152 (p < 0.0001) — slight. Comparing the median CT value for molecular swabs corresponding with the 7/34 (20.6%) antigen-positive results with that for molecular swabs corresponding with the 27/34 (79.4%) antigen-negative results showed no difference — positive: 38 (IQR: 37.5–39.5) vs negative 38.7 (IQR: 37.6–39.9); p = 0.677.

Discussion

The median age of patients corresponding with nasopharyngeal swabs testing positive by the molecular method was higher than that described by other authors in other countries. Indeed, in a retrospective review of SARS-CoV-2 molecular testing results from over 1000 hospitals across the USA, the median age of positive-testing people was 40.8 years in the period March–April 2020, decreasing to 35.8 years in June–July 2020 (Greene et al., 2020). Likewise, in epidemiological reports by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall median age was 48 years as of June 2020 (Stokes et al., 2020), declining to 37 years in July and reaching 38 years in August 2020 (Boehmer et al., 2020). Conversely, the median age of the patients included in our study was in line with a March 2020 report on case-fatality rate in Italy (Onder et al., 2020), in which individuals aged 70 years or older accounted for 37.6% of cases.

The overall sensitivity found in this study for the rapid antigen test was better than that described in most other reports for immunochromatographic tests, which have reported values from 0% to 75.5% (Fenollar et al., 2021; Lambert-Niclot et al., 2020; Mertens et al., 2020; Pérez-García et al., 2021; Scohy et al., 2020; Weitzel et al., 2021), whereas the specificity was comparable. On the other hand, in a prospective controlled observational study that evaluated 907 patients (Bianco et al., 2021), higher values of sensitivity were found; however, in that study both adults and pediatric patients were included (mean age 47.9 years) and the prevalence of disease was higher (298/907; 32.9%). In our study, from the likelihood ratios adjusted for the prevalence of the study population, it can be seen that in the presence of a positive antigen test it is 3.8 times more likely that the molecular test will also be positive rather than negative. Conversely, in the presence of a negative antigen test, the molecular test was 0.08 times more likely to be positive. The median value for RT-PCR cycles required to reach the threshold of positivity was significantly higher in molecular swabs corresponding with negative antigen tests.

For the comparative analysis in the symptomatic group, the subgroup of patients with fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea was chosen because these three main symptoms are the most frequent in patients suffering from severe disease (Borges do Nascimento et al., 2020). Therefore, the prevalence of disease in the subgroup of patients with symptoms was 38.2% and, consequently, the diagnostic accuracy of the rapid antigen test improved. Similar findings have also been reported in several studies (Fenollar et al., 2021; Lambert-Niclot et al., 2020; Mertens et al., 2020; Pérez-García et al., 2021; Scohy et al., 2020; Weitzel et al., 2021). In a systematic review and meta-analysis (Dinnes et al., 2021) that evaluated 78 study cohorts for a total of 24 087 samples, estimates of sensitivity varied between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients (72% vs 58.1%, respectively). Also in our subgroup of symptomatic patients, the median number of RT-PCR cycles required to reach the threshold was significantly higher for molecular tests corresponding with negative antigen tests.

Lower PPV values were observed in the subgroup of asymptomatic patients. Nevertheless, this meant that even in completely asymptomatic patients, almost half of the positive swabs according to the molecular test could also be identified by the rapid antigen test. This was in line with other reports — for example, in a study comparing an antigen fluorescent immunoassay with a reference molecular test, the sensitivity found in the asymptomatic patients was 41.2%, with a PPV of 33.3% (Pray et al., 2021). Likewise, in another study evaluating a rapid immunochromatographic test, in the group of 22 PCR-positive swabs from the 159 asymptomatic subjects the test showed a sensitivity of 45.4% (Fenollar et al., 2021). Even in the subgroup of asymptomatic patients, the median number of cycles of RT-PCR required to reach the threshold was significantly higher in the molecular tests corresponding with negative antigen tests.

The finding of a significantly higher median number of CTs for positive molecular tests corresponding with negative rapid antigen tests in all analyses was most probably due to the inverse correlation between viral load and CTs already described by several studies (Rao et al., 2020). Similarly, in a study that evaluated 100 nasopharyngeal swab samples collected from individuals living in a shared facility (Kohmer et al., 2021), sensitivity varied from 50% in the whole population to 100% in the subgroup of potentially infectious samples (≥ 6 log10 RNA copies/mL).

The choice to consider nasopharyngeal swabs with CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples in the final comparative analysis was driven by the study by La Scola et al. (2020), which found that that among 183 nasopharyngeal samples inoculated for virus isolation, none of the samples with CTs ≥ 34 led to virus isolation, and the study by Bullard et al. (2020), which found that, in a total of 90 samples, for every 1-unit increase in CT, the odds ratio for infectivity decreased by 32%. Even considering positive molecular swabs with CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples, the median number of CTs required to reach the threshold was significantly higher for the molecular tests corresponding with negative antigen tests. In a prospective cohort study that evaluated the same assay as our study, but in a population of 512 including children and adults (Drain et al., 2021), a sensitivity of 100% was found among the subjects with CT ≤ 33. The same analysis in our series showed an increase of 16.1% for sensitivity and of 9.4% for PPV (data not shown).

The finding of similar sensitivity values in the subgroups with main symptoms (fever and/or cough and/or dyspnea) and high viral load (CTs ≥ 35 as low viral load samples) is conceivable, since it has been found that the viral load at the time of initial sample collection is significantly higher in symptomatic than in asymptomatic patients (Kawasuji et al., 2020).

Concerning the use of this new rapid antigen test outside the hospital setting, in the light of the findings of our study and the cost of the test, some authors recommend its use only by people who have no COVID-19 symptoms and who want to exclude infection before travelling or meeting people vulnerable to an infection (Cairns, 2020).

This study had limitations. It was a single-center study, and therefore the results are not completely applicable to other settings. We were unable to test the viability of the viruses in the swabs corresponding with negative antigen tests, and the sampling methods for the two tests were different. Information regarding days after clinical onset for symptomatic COVID-19 patients was not available, and thus analysis of this factor could not be performed.

Conclusion

Compared with the molecular test considered as a reference, the new rapid antigen test showed an overall excellent diagnostic performance in a population of nearly 800 patients, in the challenging situation of an ED during the COVID-19 emergency. The diagnostic performance was better in symptomatic patients, but even in asymptomatic patients the test allowed the identification of almost half of the patients who tested positive with the molecular test, which would allow improved patient tracking and bring forward possible isolation. In each condition evaluated, the negative antigen tests corresponding with positive molecular tests required a significantly higher number of CTs for the positivity threshold. This study shows how a combination of both tests can be exploited to better establish whether a patient has a very low viral load and therefore a lower risk of infectivity.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding source

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

The work described was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. Ethical approval was not required because this was a retrospective analysis of data from samples collected as part of standard care, and those included in the database were deidentified before access. No personal information was stored in the study database. No patient intervention occurred in relation to the obtained results.

References

- Alinity m SARS-COV-2 assay. https://www.molecular.abbott/int/en/alinity-m-sars-cov-2-assay. Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Bianco G, Boattini M, Barbui AM, Scozzari G, Riccardini F, Coggiola M, et al. Evaluation of an antigen-based test for hospital point-of-care diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Virol. 2021;139 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer TK, DeVies J, Caruso E, van Santen KL, Tang S, Black CL, et al. Changing age distribution of the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1404–1409. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges do Nascimento IJ, von Groote TC, O'Mathúna DP, Abdulazeem HM, Henderson C, Jayarajah U, et al. Clinical, laboratory and radiological characteristics and outcomes of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection in humans: a systematic review and series of meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, Strong JE, Alexander D, Garnett L, et al. Predicting infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2663–2666. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E. Balancing the accuracy and cost of antigen testing, October 26, 2020. Available at: https://www.evaluate.com/vantage/articles/news/policy-and-regulation/balancing-accuracy-and-cost-antigen-testing. Accessed July 11, 2021.

- Cheng MP, Papenburg J, Desjardins M, Kanjilal S, Quach C, Libman, et al. Diagnostic testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:726–734. doi: 10.7326/M20-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Berhane S, Taylor M, Adriano A, Davenport C, et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013705.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain PK, Ampajwala M, Chappel C, Gvozden AB, Hoppers M, Wang M, et al. A rapid, high-sensitivity SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid immunoassay to aid diagnosis of acute COVID-19 at the point of care: a clinical performance study. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:753–761. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00413-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi P. Diagnostic accuracy measures. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:267–272. doi: 10.1159/000353863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenollar F, Bouam A, Ballouche M, Fuster L, Prudent E, Colson P, et al. Evaluation of the Panbio COVID-19 rapid antigen detection test device for the screening of patients with COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02589-20. e02589–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene DN, Jackson ML, Hillyard DR, Delgado JC, Schmidt RL. Decreasing median age of COVID-19 cases in the United States — changing epidemiology or changing surveillance? PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KE, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, Hayden MK, Englund JA, Lee MJ, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19: Molecular Diagnostic Testing. Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab048. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-diagnostics/ Version 2.0.0. Available at. Accessed July 5, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SA, Sheikh FN, Jamal S, Ezeh JK, Akhtar A. Coronavirus (COVID-19): a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e7355. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasuji H, Takegoshi Y, Kaneda M, Ueno A, Miyajima Y, Kawago K, et al. Transmissibility of COVID-19 depends on the viral load around onset in adult and symptomatic patients. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohmer N, Toptan T, Pallas C, Karaca O, Pfeiffer A, Westhaus S, et al. The comparative clinical performance of four SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests and their correlation to infectivity in vitro. J Clin Med. 2021;10:328. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B, Le Bideau M, Andreani J, Hoang VT, Grimaldier C, Colson P, et al. Viral RNA load as determined by cell culture as a management tool for discharge of SARS-CoV-2 patients from infectious disease wards. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:1059–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03913-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert-Niclot S, Cuffel A, Le Pape S, Vauloup-Fellous C, Morand-Joubert L, Roque-Afonso AM, et al. Evaluation of a rapid diagnostic assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in nasopharyngeal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00977-20. e00977–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffelholz MJ, Tang YW. Laboratory diagnosis of emerging human coronavirus infections — the state of the art. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:747–756. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1745095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens P, De Vos N, Martiny D, Jassoy C, Mirazimi A, Cuypers L, et al. Development and potential usefulness of the COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip diagnostic assay in a pandemic context. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:225. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi AAT, Fatima K, Mohammad T, Fatima U, Singh IK, Singh A, et al. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: structural genomics approach. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García F, Romanyk J, Gómez-Herruz P, Arroyo T, Pérez-Tanoira R, Linares M, et al. Diagnostic performance of CerTest and Panbio antigen rapid diagnostic tests to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Virol. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pray IW, Ford L, Cole D, Lee C, Bigouette JP, Abedi GR, et al. Performance of an antigen-based test for asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing at two university campuses — Wisconsin, September–October 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1642–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm695152a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SN, Manissero D, Steele VR, Pareja J. A systematic review of the clinical utility of cycle threshold values in the context of COVID-19. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:573–586. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scohy A, Anantharajah A, Bodéus M, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Verroken A, Rodriguez-Villalobos H. Low performance of rapid antigen detection test as frontline testing for COVID-19 diagnosis. J Clin Virol. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheleme T, Bekele F, Ayela T. Clinical presentation of patients infected with coronavirus disease 19: a systematic review. Infect Dis (Auckl) 2020;13 doi: 10.1177/1178633720952076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siordia JA., Jr. Epidemiology and clinical features of COVID-19: a review of current literature. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, Marder EP, Raz KM, El Burai Felix S, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:759–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technical validation for LumiraDx SARS-CoV-2 Ag test, version 1.1. Published: February 2021. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/970905/TVG_Report_LumiraDx-v2.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2021.

- Weitzel T, Legarraga P, Iruretagoyena M, Pizarro G, Vollrath V, Araos R, et al. Comparative evaluation of four rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection tests using universal transport medium. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Wunderink RG. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology. 2018;23:130–137. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]