Abstract

Objectives:

Previous work showed that higher polyp mast cell load correlated with worse postoperative endoscopic appearance in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP). Polyp epithelial mast cells showed increased expression of T-cell/transmembrane immunoglobulin and mucin domain protein 3 (TIM-3), a receptor that promotes mast cell activation and cytokine production. In this study, CRSwNP patients were followed post-operatively to investigate whether mast cell burden or TIM-3 expression among mast cells can predict recalcitrant disease.

Methods:

Nasal polyp specimens were obtained via functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) and separated into epithelial and stromal layers via enzymatic digestion. Mast cells and TIM-3-expressing mast cells were identified via flow cytometry. Mann-Whitney U tests and Cox proportional hazard models assessed whether mast cell burden and TIM-3 expression were associated with clinical outcomes, including earlier recurrence of polypoid edema and need for treatment with steroids.

Results:

Twenty-three patients with CRSwNP were studied and followed for 6 months after undergoing FESS. Higher mast cell levels were associated with earlier recurrence of polypoid edema: epithelial HR = 1.283 (P = .02), stromal HR = 1.103 (P = .02). Percent of mast cells expressing TIM-3 in epithelial or stromal layers was not significantly associated with earlier recurrence of polypoid edema. Mast cell burden and TIM-3+ expression were not significantly associated with need for future treatment with steroids post-FESS.

Conclusions:

Mast cell load in polyp epithelium and stroma may predict a more refractory postoperative course for CRSwNP patients. The role of TIM-3 in the chronic inflammatory state seen in CRSwNP remains unclear.

Keywords: chronic rhinosinusitis, mast cells, nasal polyps, TIM-3, recalcitrant

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis is a multifactorial inflammatory disorder which may be comprised of several endotypes that are not yet fully defined. Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with CRS are estimated to have nasal polyps (CRSwNP), and these patients often have significant impairment in quality of life and require treatment with systemic corticosteroids and/or endoscopic sinus surgery.1 Although there has been a substantial focus on the role of eosinophils in CRSwNP,2-4 it is apparent that there is immunologic dysfunction involving the epithelium, innate lymphoid cells, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells among other effector cells.5

T-cell or transmembrane immunoglobulin and mucin domain protein-3 (TIM-3) is a receptor that acts as an immune checkpoint, modulating immediate-phase degranulation and late-phase cytokine production downstream of FcεR1 in mast cells, promoting mast cell activation and cytokine production.6 This receptor has been implicated as an important regulator in a variety of disease states and is under investigation as a potential immunologic regulator in several types of cancers.7-10 Our group previously found increased expression of TIM-3 in epithelial mast cells derived from nasal polyps, suggesting that TIM-3 may play a role in the chronic inflammation seen in CRSwNP via mast cell activation,11 though the role of TIM-3 and mast cells in the pathophysiology of CRSwNP is not completely understood.

This work further investigates the role of mast cells in patients with CRSwNP by exploring whether mast cell burden and TIM-3-positive (TIM-3+) mast cell burden in polyp tissue is correlated with post-operative patient outcomes and more difficult to treat disease.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All patients were aged 18 years or older. All patients had disease refractory to medical management (methylprednisolone taper for 4 weeks, topical nasal steroid spray, nasal saline irrigation, and culture-directed antibiotics if appropriate). Patients with known hematological disorders, mast cell disorders, cystic fibrosis, and pregnant patients were excluded. The presence of concomitant asthma, asthma-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), or allergies did not exclude patients from the study. All patients received an oral steroid dose of methylprednisolone 32 mg daily 7 days prior to surgery, and post-surgery, patients were treated with methylprednisolone 32 mg for 3 doses, 24 mg for 3 doses, and 16 mg for 3 doses (every other day, Monday-Wednesday-Friday) concurrent with topical budesonide twice daily and saline irrigations as maintenance therapy.

Assessment of Disease Severity

Disease severity was assessed using the 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22), the Zinreich modification of the Lund-Mackay score (Z-LMK), and Lund-Kennedy (LK) score. The SNOT-22 is a validated patient-reported outcome measure of symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with CRS.12 The Z-LMK measures volume of inflammatory load in the paranasal sinuses of patients with CRS.13 LK scores quantify and stage endoscopic findings in sinus disease.14 Z-LMK and LK scores were independently assessed by authors MAB and JM, and verified for accuracy by SEL, an attending otolaryngologist. Patients were followed after functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) for continued assessment of disease severity. In addition to the aforementioned disease severity scores, the following outcomes were assessed: return of polypoid edema requiring intervention at that visit, administration of oral steroids for disease exacerbation, and administration of intra-polyp steroid injection. All assessments of disease severity and outcomes were assessed at every subsequent post-operative clinic visit. All outcome data were obtained via chart review by the first author (MAB), who was not involved in the group’s original study and played no role in medical management or intervention-decision-making for the patients.

Isolation of Mast Cells from Nasal Polyps

Our techniques for isolating and quantifying mast cells from nasal polyp specimens have been previously reported.11 Fresh nasal polyp tissue was obtained during FESS. Tissue was first separated into epithelial and stromal fractions. Epithelium was separated from the stroma via incubation in a Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA).15 Stromal fractions were obtained after collection of epithelial fractions via incubation in type II collagenase.

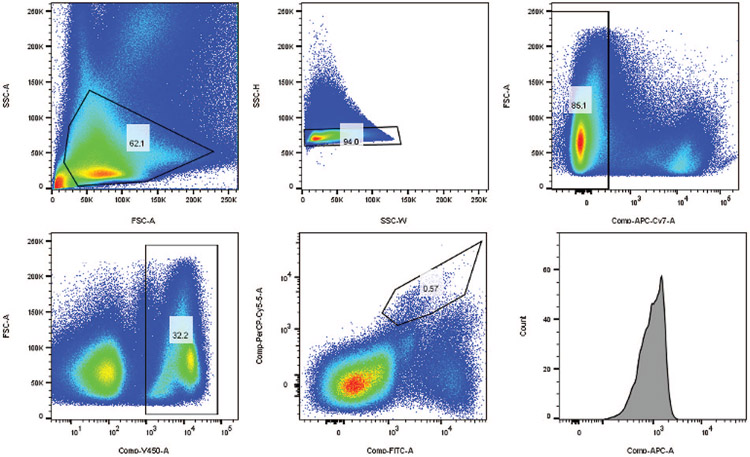

Viable mast cells were identified via flow cytometry. Dead cells were excluded by first staining with viability dye in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To avoid nonspecific staining, the solution was incubated with human plasma in 1:10 dilution with staining buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% sodium azide in PBS) prior to addition of antibodies for human CD45, c-kit, FcεR1, and TIM-3. Mast cells were identified as those cells that stained positive for CD45, c-kit, and FcεR1. Mast cell % represents the fraction of cells that stained positive for CD45, c-kit, and FcεR1 and negative for the viability dye divided by the total number of cells that stained positive for CD45 and negative for viability dye. TIM-3 mast cell % represents the fraction of cells that stained positive for TIM-3, CD45, c-kit, and FcεR1, but negative for viability dye, divided by the total number of cells positive for CD45, c-kit, and FcεR1 and negative for viability dye. Figure 1 shows the gating strategy for identification and isolation of TIM-3+ mast cells via flow cytometry. Stained cells were subsequently fixed with 1.5% paraformaldehyde and analyzed on a BD LSR II or FORTESSA flow cytometers. Unstained and fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) control samples were included for each analysis. FlowJo 8.7 Flow Cytometry software (FlowJo, Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA) was used to complete all flow cytometry analyses.

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the gating strategy for identification and isolation of TIM-3 mast cells through flow cytometry.

Antibodies and Reagents

The following were used for mast cell isolation: calcium- and magnesium-free HBSS (Lonza, Walkersville, Maryland), HEPES (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, Utah), EDTA (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, New Jersey), type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp, Lakewood, New Jersey). The following dyes were used for flow cytometry: anti-human CD45 (violetFluor 450 clone HI30, Tonbo Biosciences, San Diego, California), Ghost Red 780 viability dye (APC-Cy7, Tonbo Biosciences); anti-human FcεR1 (FITC, eBioscience Affymetrix Inc, San Diego, California), anti-human c-kit (PerCP-Cy5.5, BD Biosciences, San Jose, California), and anti-human TIM-3 (APC, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota).

Statistical Analysis

Two analyses were planned for this study. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare mast cell load between those with and without each outcome at any time in the follow-up period. Cox proportional hazard models assessed whether mast cell burden was associated with earlier recurrence of polypoid edema or need for oral/injected steroid treatment using data from all follow-up visits within 6 months after surgery: We chose this time frame to indicate a more refractory disease course after FESS.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Polyp tissue was obtained from 23 patients undergoing FESS for medical-treatment-refractory, symptomatic CRSwNP. Demographics are presented in Table 1. All patients experienced improvement in symptoms/quality of life as measured by SNOT-22 score after FESS, as well as improved endoscopic appearance as measured by LK scores, at their first follow-up visit. The median change in SNOT-22 score, from pre-operative appointment to first post-operative appointment, was a decrease of 23; the minimal clinically important difference in SNOT-22 score has been reported as 8.9.12

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (n = 23).

| Age | 52.2 (38.6, 60.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 13 (56.5%) |

| Female | 10 (43.5%) |

| Race | |

| White | 22 (95.7%) |

| Black | 1 (4.3%) |

| History of smoking | 8 (34.8%) |

| Concomitant asthma | 14 (60.9%) |

| Concomitant allergic rhinitis | 17 (73.9%) |

| AERD | 6 (26.1%) |

| Pre-operative Z-LMK | 31 (24, 44) |

| Pre-operative SNOT-22 | 42 (32, 64) |

| Post-operative SNOT-22 | 25 (9, 41) |

| Pre-operative LK | 8 (5, 10) |

| Post-operative LK | 4 (2, 6) |

Note. Categorical data presented as n (%). Ordinal and interval data presented as median (Q1, Q3).

Abbreviations: LK, “Lund-Kennedy Score”; SNOT-22, “Sino-Nasal Outcome Test Score”; Z-LMK, “Zinreich Lund-Mackay Score.”

Six-Month Follow-Up

Table 2 highlights the relationship between mast cell burden in nasal polyp samples obtained during FESS and disease outcomes in the 6 months following surgery. Cox proportional hazard models revealed that higher mast cell levels in both epithelial and stromal layers were associated with earlier recurrence of polypoid edema. For epithelial mast cells, the estimated HR = 1.283 (95% Confidence Interval 1.05–1.57, P = .02). For stromal mast cells, the estimated HR = 1.103 (95% Confidence Interval 1.01–1.20, P = .02). There were no statistically significant relationships between mast cell percentages in either tissue layer and prescription of oral corticosteroids or administration of injected steroids. In Mann-Whitney U analyses, there were no statistically significant associations between mast cell burden and occurrence of clinical outcomes, including recurrence of polypoid edema. TIM-3+ mast cells percentages were not significantly associated with any outcomes.

Table 2.

Mast Cells and Outcomes within 6 Months.

| Polypoid edema |

Oral corticosteroids prescribed |

Steroid injection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Total count (%) | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | 6 (26.1) | 17 (73.9) | 4 (17.4) | 19 (82.6) |

| % Mast cells, epithelial | 7.27 (2.28, 10.10) | 2.19 (1.26, 6.26) | 2.76 (1.21, 8.09) | 3.49 (1.26, 7.84) | 6.24 (1.10, 9.66) | 2.50 (1.41, 7.56) |

| % Mast cells, stromal | 10.60 (0.20, 18.70) | 0.79 (0.23, 3.84) | 1.71 (0.75, 22.78) | 0.58 (0.21, 11.60) | 11.60 (2.67, 26.70) | 0.99 (0.22, 4.07) |

| % TIM-3+ mast cells, epithelial | 20.00 (3.65, 76.70) | 32.80 (7.00, 78.20) | 34.15 (6.05, 94.68) | 25.60 (3.83, 73.50) | 26.07 (2.32, 87.08) | 25.60 (11.98, 75.10) |

| % TIM-3+ mast cells, stromal | 9.13 (1.60, 32.20) | 5.24 (0.61, 37.80) | 20.67 (1.76, 46.18) | 4.69 (0.81, 25.55) | 16.72 (0.81, 32.80) | 8.23 (0.95, 28.50) |

Note. For total count, data presented as n (%). All other data presented as median (Q1, Q3).

Higher epithelial and stromal median mast cells percentages were present in the 7 patients with polypoid edema recurrence within 6 months (7.27% for epithelial layer and 10.60% for stromal layer) compared to the 16 patients without polypoid edema recurrence (2.19% for epithelial layer and 0.79% for stromal layer). Median TIM-3+ mast cell percentages were higher in epithelial layers from patients who did not have polypoid edema (32.8%) compared to patients who did have polypoid edema return within 6 months (20.0%) but lower in the stromal layers for patients who did not have polypoid edema return (5.24%) compared to those who did (9.13%).

Investigation of Patients with Return of Polypoid Edema within 6 months

Table 3 highlights detailed clinical data for the patients who had return of polypoid edema within 6 months: included data are clinical and demographic characteristics as well as clinical severity scores at pre-operative visits and the visit in which polypoid edema recurred. Four of 7 patients had concomitant asthma diagnoses, 3 had a concomitant diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, and 1 patient had AERD. The median pre-operative SNOT-22 score for this subset of patients was 39, the median pre-operative LK score was 8, and the median pre-operative Z-LMK score was 31. SNOT-22 scores at return visits with return of polypoid edema were lower compared to the pre-operative scores in 5 of these patients, though 1 patient had an increased SNOT-22 score and 1 patient reported a score at 0 at both the pre-operative and post-operative visit. At the visit in which polypoid edema was found to recur, 4 patients had LK scores lower than their pre-operative LK score, 1 patient had an equivalent LK score, and 2 patients had higher LK scores compared to their pre-operative score.

Table 3.

Details for Patients with Return of Polypoid Edema within 6 Months.

| ID | Age | Sex | Asthma | AERD | Allergic rhinitis | SNOT-22 pre-op, F/U | LK pre-op, F/U | Z-LMK pre-op | Days post-op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | M | Y | Y | Y | 33, 18 | 8, 8 | 47 | 129 |

| 2 | 26 | M | N | N | N | 39, 22 | 4, 8 | 31 | 82 |

| 3 | 54 | F | N | N | N | 85, 20 | 8, 6 | 46 | 151 |

| 4 | 48 | F | Y | N | Y | 58, 49 | 6, 2 | 23 | 45 |

| 5 | 52 | M | N | N | N | 0, 0 | 4, 8 | 32 | 87 |

| 6 | 55 | M | N | N | N | 22, 16 | 8, 4 | 24 | 80 |

| 7 | 49 | M | Y | N | Y | 24, 31 | 8, 6 | 7 | 45 |

| Group summary | 49.3 (26.4-55.2) | 5/7 M 71% M | 4/7 57% | 1/7 14% | 3/7 43% | 39, 21 (0-85), (0-49) | 8, 6 (4-8), (2-8) | 31 (17-47) | 82 (45-151) |

Note. Scores reported at time of pre-operative visit and follow-up visit in which polypoid edema was found to recur (F/U). “Days Post-Op” refers to the follow-up time at which polypoid edema recurred, though all patients were followed-up for at least 6 months after surgery. For group summary statistics, categorical data presented as n/total and %. Ordinal and interval data presented as median (min-max).

Abbreviations: LK, “Lund-Kennedy Score”; N, “No”; SNOT-22, “Sino-Nasal Outcome Test Score”; Y, “Yes”; Z-LMK, “Zinreich Lund-Mackay Score.”

Discussion

This study adds to a growing body of literature that demonstrates a potential role of mast cells in the course of CRSwNP. Mast cell burden within epithelial and stromal components of nasal polyps at time of surgery was related to earlier recurrence of polypoid edema within 6 months after surgery in our cohort of patients in Cox proportional hazard model analyses. In our second pre-planned analysis, Mann-Whitney U tests did not find statistically significant associations between mast cell burden and return of polypoid edema at any time, though effect sizes were large, as patients with return of polypoid edema had median mast cell burdens that were over 3 times larger in the epithelial layer and over 10 times larger in the stromal layer. Mast cell burden was not related to earlier administration of oral or intra-polyp steroid injection. Percent of TIM-3+ mast cell levels did not appear to be related to clinical outcomes.

As in our first study, overall mast cell burden in polyp tissue was the major statistically significant predictor for a primary outcome studied (recurrence of polypoid edema). Although TIM-3 appears to be more commonly expressed in epithelial layers of polyp tissue, the percent of epithelial TIM-3-expressing mast cells was not significantly associated with earlier return of polypoid edema, similar to our original study in which TIM-3+ mast cell burden was not significantly correlated with post-operative endoscopic appearance in the entire study group. One potential explanation for this is the heterogeneity of TIM-3 expression in polyp mast cells: The interquartile range for epithelial %TIM-3+ mast cells was 73.05%, and the interquartile range for stromal %TIM-3+ was 30.6%. This wide range of TIM-3 expression across polyp specimens make it difficult to interpret how TIM-3 plays a role in the polyp’s cellular or molecular inflammatory environment. Future studies are needed to better understand this role.

Our finding that increased total percent mast cells within polyps was significantly related to early recurrence of polypoid edema suggests that higher mast cell burden at time of surgery could predict a more recalcitrant disease course for patients with CRSwNP. Mast cell levels could potentially serve as a biomarker for a more severe disease endotype. Efforts to characterize the endotype or pathomechanism of the immune response in patients with CRS via cluster analysis of inflammatory markers, clinical features, cellular composition, and nasal secretions are underway.16-19 Further investigation of biomarkers to prognosticate disease severity and tailor treatment regimens for patients with CRSwNP is needed.20

Seven patients in this study appeared to form a subgroup with more difficult to treat disease, as they all experienced return of polypoid edema within only 6 months after FESS. Interestingly, these patients were not identifiable as a group with more severe disease pre-operatively based on clinical severity scores, with lower median SNOT-22 score and equivalent median LK and Z-LMK scores compared to entire cohort. Additionally, this subgroup was not composed exclusively of patients with concomitant conditions (asthma, AERD, allergic rhinitis) that may have been expected to have more severe disease: Four of these 7 patients had no concomitant diagnoses. SNOT-22 scores and LK scores after polypoid edema recurrence generally indicated that disease was less severe than it was pre-operatively, although some patients did have slightly worsened symptom burden by SNOT-22 score (1 patient) or endoscopic appearance by LK score (2 patients). In light of our study’s overall finding that increased mast cell burden at time of FESS was associated with earlier recurrence of polypoid edema, mast cell burden in polyps could serve as a more reliable predictor of future disease course than pre-operative clinical severity or other comorbidities.

Much of the work in our field on understanding the pathophysiology of polyp formation focuses on the role of eosinophils, and several medical therapy clinical trials have focused on disrupting the effects of eosinophils on the chronic inflammatory state observed in CRSwNP. Eosinophil burden in blood and tissue have also been studied to determine patient outcomes.21-23 However, the results of some studies have suggested that other mediators may be more important in the propagation of nasal polyps. In an open-label study on dexpramipexole, a medication known to decrease blood eosinophils, there was a 94% reduction in blood eosinophils and a 97% reduction in tissue eosinophils but interestingly no impact on total polyp score or nasal symptom improvement.24

Although understudied, mast cells may play an important role in the pathophysiology of polyp formation in patients with CRSwNP. The underlying inflammatory pathway seen in CRSwNP is categorized as a Type 2 inflammatory response, with expression of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and increased concentrations of IgE.1,25,26 It is apparent that there are other types of inflammation underlying CRSwNP including Type 1, Type 3, and perhaps variations of the three.5 Baba et al27 found that patients with eosinophilic CRSwNP had a specific distribution, subtype population, and IgE positivity of mast cells compared to patients with non-eosinophilic CRSwNP, with increased numbers of tryptase positive mast cells in polyp epithelium, suggesting a role of mast cells in polyp development. Zhai et al28,29 have implicated IgD-activated mast cells and CD30L+ mast cells in eosinophilic inflammation in CRSwNP. Other investigations have focused specifically on mast cells, finding increased activity or burden of these cells in patients with CRSwNP.27-29 Takabayashi et al30 demonstrated localization of mast cells in the glandular epithelia of nasal polyps with distinct profiles of enzyme expression: The tissue location and specific phenotypes of mast cells may further contribute to the pathogenesis of CRSwNP.

A recent study utilizing single-cell mRNA sequencing found markedly reduced epithelial cellular diversity to be a hallmark of type-2 immune-mediated barrier dysfunction and that basal progenitor cells, namely epithelial stem cells, may contribute to persistence of CRS via inflammatory memory.31 Increased expression of extracellular matrix remodeling transcripts and chemotactic factors were found for effector cells as well as decreased protease inhibitor and metabolic gene expression in polyps. Using a similar approach to study the transcriptome of mast cells would be a valuable addition to our understanding of their role in polyp genesis. Additional studies exploring the use of mast cell burden as a potential biomarker for recalcitrant CRSwNP or as an addition to endotyping schema would be valuable. Additionally, as basal epithelial cells may contribute to inflammatory memory, understanding the difference between the epithelium and underlying tissues that in turn initiate signaling cascades leading to the initiation and propagation of polypoid edema will be helpful. Further studies which separate polyp tissue into epithelial and stromal fractions may be helpful in better understanding the initiation and propagation of polypoid edema.

We recognize limitations of the present study. The small sample size allowed us to only assess associations between mast cell burden and timing of clinical outcomes in Cox proportional hazard model analyses without controlling for other covariates, as too few clinical outcomes occurred to achieve sufficient power to control for other clinical variables such as age, atopy, and AERD (which may play a role in polyp recurrence). Further studies incorporating a larger sample of patients and polyp tissues would allow for more sophisticated statistical analyses and more nuanced investigations of how concomitant diagnoses such as asthma, allergy, or AERD correlate with mast cell and TIM-3+ mast cell burden. Efforts to study appropriate comparator control tissue, such as inferior turbinate tissue from patients with CRSwNP and tissue from patients without CRSwNP, are ongoing to further assess a potential causal link between mast cells and CRSwNP and help us better understand TIM-3 expression in a non-polypoid environment. Although data were included from all follow-up visits for each patient, patients did not complete visits on a standardized schedule, which could affect time-to-event analyses. A future study with a pre-defined follow-up schedule could allow for more consistent measurements of clinical outcomes. This would also allow for the assessment of the role of post-operative medication adherence in the recurrence of polyps and other clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Mast cell burden appears to correlate with more refractory disease in CRSwNP and may be more predictive than clinical outcome measures traditionally utilized to assess disease severity. Further analysis comparing TIM-3 levels in disease vs. health is needed to make meaningful conclusions. This work raises interesting questions about the role of mast cells and TIM-3 in CRSwNP, and further work is necessary to enhance our understanding of this relationship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrea Workman for her assistance in the laboratory. We thank Dr. Nalyn Siripong at the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the University of Pittsburgh for assistance with statistical analyses.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers 1R01CA206517-01, 1R01AI138504-01A1, and UL1-TR-001857.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Stella E Lee: Clinical trial funding—Sanofi Aventis Regeneron, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca. Advisory board: Sanofi Aventis Regeneron, Novartis, Genentech

References

- 1.Stevens WW, Schleimer RP, Kern RC. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Aller Cl Imm-Pract. 2016;4(4):565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honma A, Takagi D, Nakamaru Y, et al. Reduction of blood eosinophil counts in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis after surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(12):1147–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashiwagi T, Tsunemi Y, Akutsu M, et al. Postoperative evaluation of olfactory dysfunction in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis - comparison of histopathological and clinical findings. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019;139(10):881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryu G, Kim DK, Dhong HJ, et al. Immunological characteristics in refractory chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps undergoing revision surgeries. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019;11(5):664–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu X, Ong YK, Wang Y. Novel findings in immunopathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis and their role in a model of precision medicine. Allergy. 2020;75(4):769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phong BL, Avery L, Sumpter TL, et al. Tim-3 enhances FcepsilonRI-proximal signaling to modulate mast cell activation. J Exp Med. 2015;212(13):2289–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Jiang Y, Zhang H, et al. Clinicopathological implications of TIM3(+) tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and the miR-455-5p/Galectin-9 axis in skull base chordoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(7):1157–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li F, Fan X, Wang X, et al. Genetic association and interaction of PD1 and TIM3 polymorphisms in susceptibility of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocarcinogenesis. Discov Med. 2019;27(147):79–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadadi L, Hafezi M, Amirzargar AA, et al. Dysregulated expression of Tim-3 and NKp30 receptors on NK cells of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(4):202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollica V, Di Nunno V, Gatto L, et al. Novel therapeutic approaches and targets currently under evaluation for renal cell carcinoma: waiting for the revolution. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(6):503–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corredera E, Phong BL, Moore JA, et al. TIM-3-expressing mast cells are present in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(3):581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, et al. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okushi T, Nakayama T, Morimoto S, et al. A modified Lund-Mackay system for radiological evaluation of chronic rhinosinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40(6):548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Quantification for staging sinusitis. The Staging and Therapy Group. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1995;167:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finotto S, Dolovich J, Denburg JA, et al. Functional heterogeneity of mast cells isolated from different microenvironments within nasal polyp tissue. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95(2):343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2016;137(5):1449–1456.e1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachert C, Akdis CA. Phenotypes and emerging endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachert C, Zhang N, Hellings PW, et al. Endotype-driven care pathways in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1543–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JH, Chandra RK, Li P, et al. Identification of clinically relevant chronic rhinosinusitis endotypes using cluster analysis of mucus cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1895–1897.e1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachert C, Nan Z. Medical algorithm: diagnosis and treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2020;75(1):240–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkatesan N, Lavigne P, Lavigne F, et al. Effects of fluticasone furoate on clinical and immunological outcomes (IL-17) for patients with nasal polyposis naive to steroid treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(3):213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachert C, Sousa AR, Lund VJ, et al. Reduced need for surgery in severe nasal polyposis with mepolizumab: randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2017;140(4):1024–1031.e1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Gerven L, Langdon C, Cordero A, et al. Lack of long-term add-on effect by montelukast in postoperative chronic rhinosinusitis patients with nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(8):1743–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laidlaw TM, Prussin C, Panettieri RA, et al. Dexpramipexole depletes blood and tissue eosinophils in nasal polyps with no change in polyp size. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(2):E61–E66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachert C, Gevaert P, Hellings P. Biotherapeutics in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1512–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahern S, Cervin A. Inflammation and endotyping in chronic rhinosinusitis-a paradigm shift. Medicina. 2019;55(4):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baba S, Kondo K, Suzukawa M, et al. Distribution, subtype population, and IgE positivity of mast cells in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(2):120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai GT, Li JX, Zhang XH, et al. Increased accumulation of CD30 ligand-positive mast cells associates with eosinophilic inflammation in nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(3):E110–E117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhai GT, Wang H, Li JX, et al. IgD-activated mast cells induce IgE synthesis in B cells in nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2018;142(5):1489–1499.e1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takabayashi T, Kato A, Peters AT, et al. Glandular mast cells with distinct phenotype are highly elevated in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2012;130(2):410–420.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ordovas-Montanes J, Dwyer DF, Nyquist SK, et al. Allergic inflammatory memory in human respiratory epithelial progenitor cells. Nature. 2018;560(7720):649–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]