Abstract

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are not uncommon in breast cancer patients. Western studies show that such mutations are more prevalent among younger patients. This study evaluates the prevalence of germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 among breast cancer patients diagnosed at age 40 or younger in Jordan. Blood samples of patients with breast cancer diagnosed at age 40 years or younger were obtained for DNA extraction and BRCA sequencing. Mutations were classified as benign/likely benign (non-carrier), pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant (carrier) and variant of uncertain significance (VUS). Genetic testing and counseling were completed on 616 eligible patients. Among the whole group, 75 (12.2%) had pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants; two of the BRCA2 mutations were novel. In multivariate analysis, triple-negative disease (Odd Ratio [OR]: 5.37; 95% CI 2.88–10.02, P < 0.0001), breast cancer in ≥ 2 family members (OR: 4.44; 95% CI 2.52–7.84, P < 0.0001), and a personal history ≥ 2 primary breast cancers (OR: 3.43; 95% CI 1.62–7.24, P = 0.001) were associated with higher mutation rates. In conclusion, among young Jordanian patients with breast cancer, mutation rates are significantly higher in patients with triple-negative disease, personal history of breast cancer and those with two or more close relatives with breast cancer.

Subject terms: Health care, Medical research, Oncology, Risk factors

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 20% of all cancer cases diagnosed in developing and developed countries1,2.A total of 1145 cases were reported by the Jordan Cancer Registry (JCR) in its latest annual report3. Similar to many low- and middle-income countries4, the median age at breast cancer diagnosis in Jordan is only 52 years, which is ten years younger than most Western societies5,6. Additionally, more than a third of patients present with locally-advanced or metastatic disease7,8.

Though most breast cancer cases are sporadic, 5–10% of cases are hereditary and mostly related to BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations9. However, with the widespread use of genetic testing, mutations other than BRCA1 and BRCA2 are currently detected. Such mutations include ATM, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, STK11, and TP5310–12.

Studies had shown that both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are associated with a high penetrance rate. The cumulative risk estimates for developing breast cancer by age 80 are 70–90% for carriers of BRCA1 pathogenic variants and 60–70% for BRCA2 carriers. The cumulative risk for developing ovarian cancer is a little lower; 40–50% for BRCA1 carriers and around 20% for BRCA2 carriers13,14. Additionally, the risk of contralateral breast cancer, 20 years after the initial diagnosis, is 40% and 26% for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, respectively15.

Because of this high penetrance rate and its associated significant consequences, identifying such mutations should be actively sought in high-risk patients identified by international guidelines13. Risk-reduction interventions, like bilateral mastectomies and salpingo-oophorectomies, are highly recommended for patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers, especially so among younger patients.

In addition to its value in preventing breast and ovarian cancers, identification of mutation carriers may have therapeutic importance in patients with breast cancer, too. Recent data had suggested that patients with advanced-stage breast cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations may benefit from PARP (poly ADP ribose polymerase) inhibitors like olaparib and talazoparib; both are currently approved for such situation16–18.

Data related to hereditary breast cancer among Arabs, particularly Jordanians, is scarce. Reported pathogenic variant carrier rates vary19–22. It is unknown if inherited germline mutations account for earlier age at breast cancer diagnosis in our region. We recently reported our experience on 517 high risk patients treated and followed at our institution; a total of 72 (13.9%) patients had pathogenic or likely pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, while 53 (10.3%) others had a variant of uncertain significance (VUS)23.

The diagnosis of breast cancer in young women and its possible genetic implications have potentially serious consequences for patients and their family members, too. Physicians and genetic counselors can help navigate such complex medical and psychosocial issues. In this paper, we aim to study the prevalence and pattern of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among a group of young Jordanian patients with breast cancer thought to be at higher risk for such mutations.

Methods

Jordanian breast cancer patients aged 40 years or younger at the time of diagnosis were invited for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing as part of our clinical practice guidelines. Family history or personal history of breast, or other cancers, were not mandated for eligibility. All patients had their diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up at our center.

Eligible patients were identified at their first encounter by a medical oncologist or following the weekly breast multidisciplinary team meetings. Eligible patients who consented to be tested were then referred to a specialized genetic counseling clinic where all potential psychosocial and clinical consequences of positive test results were discussed.

As recommended by international guidelines15, BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants were classified as benign/likely benign (non-carrier), pathogenic/likely pathogenic (carrier) and VUS. Clinical details and pathological characteristics of the tumors were reviewed. Additionally, a detailed 3-generation family history was also obtained. Estrogen (ER) or progesterone receptors (PR) were positive if tumor cell nuclei staining is ≥ 1%. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) was tested using a standardized immune histochemical staining (IHC), and tumor cells were considered negative with scores of 0 or + 1, and positive for those with + 3 scores. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed for equivocal samples with + 2 scores. Triple-negative tumors are those which tested negative for ER, PR, and HER-2.

Blood samples were obtained for DNA extraction, full-gene sequencing, and deletion/duplication analysis for BRCA1 and BRCA2 using next-generation sequencing technology (NGS) and/or Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) analysis were performed at three reference labs: Myriad Genetics laboratory (Salt Lake City, UT), Leeds Cancer Center (Leeds, United Kingdom) and invitae (San Francisco, CA).

Our study was carried out in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at King Hussein Cancer Center. All patients signed informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ clinical and pathologic characteristics were collected, tabulated, and described by ranges, medians, or percentages. Relatives diagnosed with breast cancer and tested after the family’s index case were not enrolled and were excluded from the analysis. Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportion of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant carriers according to age (≤ 30 versus > 30), triple-negative status, and family history. Multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model was performed. Odds ratios and their related 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using Minitab Statistical Software version 18 (Minitab 18 Statistical Software (2017). State College, PA: Minitab, Inc. (www.minitab.com).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by King Hussein Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). All patients signed informed consent.

Consent for publication

Data submitted are entirely unidentifiable and there are no details on individuals reported within the manuscript. Request to publish was approved by King Hussein Cancer Center IRB.

Results

Between November 2016 and January 2020, 616 eligible patients were recruited. Participants’ median age was 35 (range 19–40) years, and 121 (19.6%) patients were 30 years or younger. The majority (n = 482, 78.2%) of the patients had hormone receptor (ER and/or PR) positive disease. HER-2 testing was available on 547 patients, 180 (32.9%) were positive by IHC and/or FISH, and 69 (12.6%) had triple-negative disease Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics (n = 616).

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | Median | 35 | |

| Range | 19–40 | ||

| Hormonal status | ER-positive | 449 | 73.0 |

| PR-positive | 438 | 71.0 | |

| ER and/or PR-positive | 482 | 78.2 | |

| ER and PR-negative | 134 | 22.0 | |

| HER-2 status* | HER2-positive | 180 | 32.9 |

| HER2-negative | 367 | 67.1 | |

| Unknown | 68 | 12.4 | |

| Triple negative* | 69 | 12.6 | |

| Positive family history of breast cancer | 499 | 81.0 | |

*Percentage from 547 with known HER2 status.

ER estrogen receptors, PR progesterone receptors, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

Among the whole group, 75 (12.2%) patients had pathogenic/likely pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations; 50 (66.7%) were in BRCA2, while an additional 57 (9.3%) had a VUS (Supplementary Table S1). Patients with at least two breast cancer primaries (n = 48) had a significantly high mutation rate (n = 8, 29.2%). Table 2 presents mutation rates according to different categories.

Table 2.

Rates of positive BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations; subgroup analysis.

| Variable | Total | Positive Mutations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | BRCA2 | BRCA1& BRCA2 | P-Value* | |||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ≤ 35 | 341 | 16 | 34 | 50 (14.7%) | 0.017 |

| > 35 | 275 | 9 | 16 | 25 (9.1%) | ||

| One or more close relative with breast cancer at any age | Yes | 305 | 9 | 37 | 46 (15.1%) | 0.029 |

| No | 311 | 15 | 14 | 29 (9.3%) | ||

| One or more close relatives with breast cancer diagnosed at age 50 years or younger | Yes | 153 | 3 | 24 | 27 (17.6%) | 0.017 |

| No | 463 | 22 | 26 | 48 (10.4%) | ||

| Diagnosed at ≤ 60 years with triple negative disease | Yes | 69 | 16 | 7 | 23 (33.3%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 547 | 9 | 43 | 52 (9.5%) | ||

| Any age with at least 2 breast cancer primaries | Yes | 48 | 6 | 8 | 14 (29.2%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 568 | 19 | 42 | 61 (10.7%) | ||

| Two or more close relatives with breast cancer | Yes | 97 | 5 | 24 | 29 (30.0%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 519 | 20 | 26 | 46 (8.9%) | ||

| All patients | 616 | 25 | 50 | 75 (12.2%) | ||

Family history

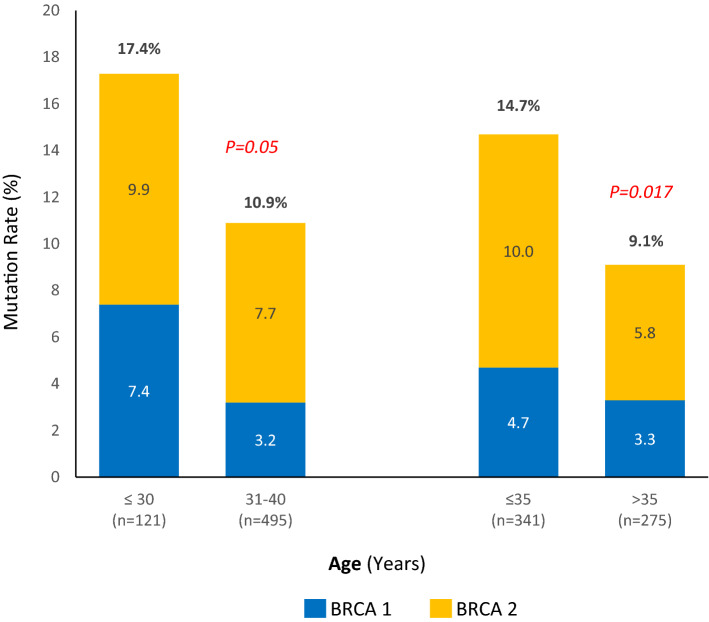

The majority of the patients enrolled (n = 499, 81.0%) had a positive family history of breast cancer in first-, second- or third-degree family members. Women with two or more close relatives diagnosed at any age with breast cancer (Group-A, n = 97) had the highest mutation rate (n = 29, 30.0%). In contrast, women with one or more family members diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50 years (Group-B, n = 153) had a mutation rate of 17.6%, P = 0.011. The mutation rate was lower (15.1%, P = 0.001) among women with one or more family members diagnosed at any age (Group-C, n = 305), Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation rates by family history. (A) Two or more close relatives with breast cancer. (B) One or more close relatives with breast cancer diagnosed at age 50 years or younger. (C) One or more close relatives with breast cancer at any age.

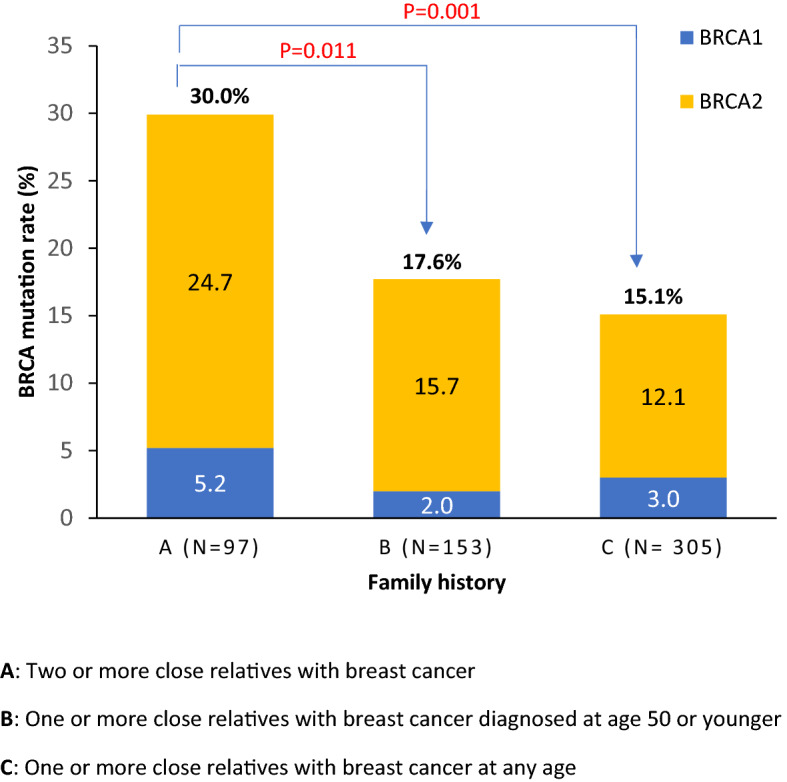

Age at diagnosis

We studied the contribution of age to mutation rate in two ways. First, we compared mutation rates across the median age of our cohort; BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants were reported in 14.7% of 341 patients aged ≤ 35 years, compared to 9.1% in 275 patients older than 35 years, P = 0.017. Second, we compared mutation rates across two age groups: < 30 years and those aged 31–40 years; mutation rates were 17.4% and 10.9% (P = 0.05), respectively, Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation rates by age group.

Triple-negative disease

Patients with triple-negative disease (n = 69) had significantly higher rates (n = 23, 33.3%) compared to 9.5% among non-triple negative patients, P < 0.001. Most of the pathogenic variants were in BRCA1 (n = 16, 23.2%), and the majority (n = 54, 78.3%) of such patients had a positive family history of breast cancer; only 2 (13.3%) of the 15 patients with no family history had a pathogenic variant.

Multivariate analysis

In the multivariate analysis, triple-negative disease (Odds Ratio [OR]: 5.37; 95% CI 2.88–10.02, P < 0.0001), breast cancer in two or more family members (OR: 4.44; 95% CI 2.52–7.84, P < 0.0001), and a personal history of two or more primary breast cancer (OR: 3.43; 95% CI 1.62–7.24, P = 0.001), were associated with higher BRCA mutation rates.

Mutation types

A spectrum of 39 different mutations, 22 in BRCA2 and 17 in BRCA1, were detected (Tables 3 and 4). To our knowledge, two mutations in BRCA2 (c.6193C > T in exon 11 and c.1013del in exon 10) have not been reported previously in any database. Additionally, five unrelated females in our cohort were found to harbor two concomitant mutations in BRCA2 exon11 (c.2254_2257del) and (c.5351dup), simultaneously (Table 4). These two mutations appeared separately in a very limited number of studies24–26. Except for mutations c.1233dup and c.9257-1G>A/IVS24-1G>A, for which two family members were tested for each, all other variants have been detected in different families. Nineteen (25.3%) of the mutations detected in our patients were either (c.2254_2257del) or (exon 5–11 duplication); both in BRCA2 gene and were detected in 11 and 8 different patients, respectively.

Table 3.

Types of BRCA1 mutations.

| Gene | Exon/intron | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Variant type | Database report | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA 1 | Exon 1–2 | Deletion (exons 1–2) | Absent or disrupted protein product | Large deletion | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 2 | c.66dup | p.Glu23Argfs | Duplication/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 3 | c.121C > T | p.His41Tyr | Missense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 10 | c.3835del | p.Ala1279Hisfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.3436_3439del | p.Cys1146LeufsTer | Deletion/fs | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.798_799del | p.Ser267Lysfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.2761C > T | p.Gln921Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.1961del | p.Lys654Serfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.809del | p.His270Leufs | Deletion/ fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 11 | c.4065_4068del | p.Asn1355Lysfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 12 | c.4117G > T | p.Glu1373Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 4 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 15 | c.4524G > A | p.Trp1508Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 17 | c.5030_5033del | p.Thr1677Ilefs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 18 | c.5123C > A | p.Ala1708Glu | Missense | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 18 | c.5095C > T | p.Arg1699Trp | Missense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Exon 19 | c.5161C > T | p.Gln1721Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 1 | Intron 17 | c.5074 + 3A > G/ IVS17 + 3 | Splice acceptor | Intervening sequence | Yes | 3 |

Table 4.

Types of BRCA2 mutations.

| Gene | Exon/intron | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Variant type | Database report | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA 2 | Exons 5–11 | exon 5–11 duplication | Absent or disrupted protein product | Large duplication | Yes | 8 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 8 | c.658_659del | p.Val220Ilefs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 10 | c.1233dup | Pro412Thrfs | Duplication/fs | Yes | 5 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 10 | c.1013del | p.Ala338Metfs | Deletion/fs | No | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.2254_2257del | p.Asp752Phefs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 11 |

| BRCA 2 |

Exon11/ Exon11 |

c.2254_2257del & c.5351dup | p.Asp752Phefs & p.Asn1784Lysfs | Deletion/fs-Duplication/fs | No | 5 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6685G > T | p.Glu2229Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 3 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6486_6489del | p.Lys2162Asnfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.4222_4223del | p.Gln1408Argfs | Deletion/fs | No | 2 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6627_6634del | p.Ile2209Metfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.2677C > T | p.Gln893Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6193C > T | p.Gln2065Ter | Nonsense | No | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.2808_2811del | p.Ala938Profs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.4936_4939del | p.Glu164Gln6fs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.5722_5723del | p.Leu1908Argfs | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6445_6446del | p.Ile2149Ter | Deletion/fs | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 11 | c.6022A > T | p.Lys2008Ter | Missense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 13 | c.7007G > A | p.Arg2336His | Missense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 18 | c.8140C > T | p.Gln2714Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 22 | c.8878C > T | p.Gln2960Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 2 |

| BRCA 2 | Exon 22 | c.8760 T > G | p.Tyr2920Ter | Nonsense | Yes | 1 |

| BRCA 2 | Intron 24 | c.9257-1G > A/ IVS24-1G > A | Splice acceptor | Intervening sequence | Yes | 3 |

Discussion

Our study confirms that younger patients are at a higher risk of harboring pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations and such risk is higher for patients younger than 30 years at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. However, differences in mutation rates between patients above or below 40 years is less obvious. In one of our previous studies, the mutation rate among 333 younger patients (≤ 40 years) was 13.2% compared to 15.2% among 184 older ones, P = 0.5323.

Our findings of two novel mutations that have been detected in our database as well as a higher frequency of certain mutations like (c.2254_2257del) and (exon 5–11 duplication) will probably have an important consequence for the genetic testing of BRCA genes in Jordan where consanguineous marriage is relatively common. In one study, researchers reviewed published and unpublished data to identify population‐specific founder BRCA pathogenic sequence variants (PSVs) in Middle East, North Africa, and Southern Europe; 232 PSVs in BRCA1 and 239 in BRCA2 were identified27.

It is also worth highlighting that our study identifies three risk factors, the presence of any of which in younger patients increases the pathogenic variant carrier rate to almost one in three tested patients. These include, patients with triple-negative disease, women with at least two breast primaries, and those with a family history of breast cancer in two or more close relatives diagnosed at any age. Such findings might help simplify our efforts to educate both patients and health care providers about the importance of genetic testing and counseling for such patients.

Our VUS rate (9.3%) is higher than what had been reported among Caucasian patients28. This rate will probably go even higher with the wider implementation of multi-gene testing. Several studies had shown higher VUS rates among African-Americans, Hispanics and patients of Ashkenazi–Jewish descent29–31.

We have built a good experience in dealing with patients before and after testing. Ensuring confidentiality was never a problem in our current daily practice. Very few patients refused genetic testing and counseling because of their fear of stigmatization and labeling. However, prophylactic bilateral mastectomies and oophorectomies with reconstructive surgery can be a challenge. Studies addressing the psychosocial consequences of pathogenic variants especially among younger patients in our region, are highly needed.

Though our study represents a single-center, we believe it reflects the whole country as our institution treats most of the country’s breast cancer cases. However, our study is not without limitations; issues related to psychosocial aspects related to pathogenic variant carrier state, risk-reduction surgeries, fertility-related issues, and outcome of family members at-risk of index cases need to be followed and addressed.

Conclusions

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation rates among patients 40 years or younger are relatively high but not necessarily higher than older patients. However, personal and family risk factors can identify subgroups of younger patients with much higher mutation rates.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Razan Abu Khashabeh from the Department of Cell Therapy & Applied Genomics, our IRB, and the research office for their help in conducting this research.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence intervals

- ER

Estrogen receptors

- FISH

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IRB

Institutional review board

- MLPA

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- NCCN

National comprehensive cancer network

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- OR

Odds ratio

- PR

Progesterone receptors

- PARP

Poly ADP ribose polymerase

- VUS

Variant of uncertain significance

Author contributions

H.A. conceived the research idea, planned it, supervised data collection, and took the lead in writing the manuscript. L.A. consulted with patients, supervised informed consent, sample collection, genetic counseling, and participated in analyzing the data. M.A., S.E., and R.B. participated in analyzing the data and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

Data will not be available online as it might contain sensitive information. Data will be available through the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-94403-1.

References:

- 1.Torre L, Islami F, Siegel R, Ward E, Jemal A. Global cancer in women: Burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2017;26:444–457. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer incidence in Jordan- Ministry of Health. Moh.gov.jo (2015). at https://www.moh.gov.jo/Pages/viewpage.aspx?pageID=240

- 4.Bidoli E, Virdone S, Hamdi-Cherif M, et al. Worldwide age at onset of female breast cancer: A 25-year population-based cancer registry study. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50680-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Razeq H, Mansour A, Jaddan D. Breast cancer care in Jordan. J. Glob. Oncol. 2020;6:260–268. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson ET. Breast cancer acial differences before age 40–implications for screening. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2002;94:149–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chouchane L, Boussen H, Sastry K. Breast cancer in Arab populations: Molecular characteristics and disease management implications. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e417–e424. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Saghir N, Khalil M, Eid T, et al. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing Arab countries: A literature and registry analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2007;5:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen M, Thomassen M, Gerdes A, Kruse T. Hereditary breast cancer: Clinical, pathological and molecular characteristics. Breast Cancer: Basic Clin. Res. 2014;8:8715. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S18715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh T, Casadei S, Coats K, et al. Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295:1379. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rainville I, Rana H. Next-generation sequencing for inherited breast cancer risk: Counseling through the complexity. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2014;16:2. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0371-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoniou A, Casadei S, Heikkinen T, et al. Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:497–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCCN Guidelines, Genetic/Familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian. Version1. 2020. at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf

- 14.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machackova E, Claes K, Mikova M, et al. Twenty years of BRCA1 and BRCA2 molecular analysis at MMCI—current developments for the classification of variants. Klin Onkol. 2019;32(Supplementum2):51–71. doi: 10.14735/amko2019S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner N, Telli M, Rugo H, et al. A phase II study of talazoparib after platinum or cytotoxic nonplatinum regimens in patients with advanced breast cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutations (ABRAZO) Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;25:2717–2724. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litton J, Rugo H, Ettl J, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:753–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turk A, Wisinski K. PARP inhibitors in breast cancer: Bringing synthetic lethality to the bedside. Cancer. 2018;124:2498–2506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Razeq H, Al-Omari A, Zahran F, Arun B. Germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations among high risk breast cancer patients in Jordan. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troudi W, Uhrhammer N, Romdhane K, et al. Complete mutation screening and haplotype characterization of BRCA1 gene in Tunisian patients with familial breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2008;4:11–18. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2008-4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasan T, Shafi G, Syed N, Alsaif M, Alsaif A, Alshatwi A. Lack of association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants with breast cancer in an ethnic population of Saudi Arabia, an emerging high-risk area. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5671–5674. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.10.5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jalkh N, Nassar-Slaba J, Chouery E, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in familial breast cancer patients in Lebanon. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2012;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Razeq H, Abujamous L, Al-Omari A, Tbakhi A, Jadaan D. Abstract P2–09-06: Genetic counseling and genetic testing for germline BRCA1/2 mutations among high risk breast cancer patients in Jordan: A study of 500 patients. Poster Sess. Abstracts. 2020 doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.sabcs19-p2-09-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solano A, Liria N, Jalil F, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than the founder alleles among Ashkenazi Jewish in the population of Argentina. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:2. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janavičius R. Founder BRCA1/2 mutations in the Europe: Implications for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer prevention and control. EPMA J. 2010;1:397–412. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0037-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farra C, Dagher C, Badra R, et al. BRCA mutation screening and patterns among high-risk Lebanese subjects. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2019;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s13053-019-0105-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laitman Y, Friebel TM, Yannoukakos D, et al. The spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic sequence variants in Middle Eastern, North African, and South European countries. Hum. Mutat. 2019;40:e1–e23. doi: 10.1002/humu.23842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chern J, Lee S, Frey M, Lee J, Blank S. The influence of BRCA variants of unknown significance on cancer risk management decision-making. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019;30:2. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Culver J, Brinkerhoff C, Clague J, et al. Variants of uncertain significance inBRCAtesting: Evaluation of surgical decisions, risk perception, and cancer distress. Clin. Genet. 2013;84:464–472. doi: 10.1111/cge.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calò V, Bruno L, La Paglia L, et al. The clinical significance of unknown sequence variants in BRCA genes. Cancers. 2010;2:1644–1660. doi: 10.3390/cancers2031644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eccles D, Mitchell G, Monteiro A, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing—pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:2057–2065. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be available online as it might contain sensitive information. Data will be available through the corresponding author on reasonable requests.