Abstract

Quantifying deadwood decomposition is prioritized by forest ecologists; nonetheless, uncertainties remain for its regional variation. This study tracked variations in deadwood decomposition of Korean red pine and sawtooth oak in three environmentally different regions of the Republic of Korea, namely western, eastern, and southern regions. After 24 months, dead pine and oak woods lost 47.3 ± 2.8% and 23.5 ± 1.6% in the southern region, 13.3 ± 2.6% and 20.2 ± 2.8% in the western region, and 11.9 ± 7.9% and 13.9 ± 2.3% in the eastern region, respectively. The regional variation in the decomposition rate was significant only for dead pine woods (P < 0.05). Invertebrate exclusion treatment reduced the decomposition rate in all region, and had the greatest effect in the southern region where warmer climate and concentrated termite colonization occurred. The strongest influential factor for the decomposition of dead pine woods was invertebrate exclusion (path coefficient: 0.63). Contrastingly, the decomposition of dead oak woods was highly controlled by air temperature (path coefficient: 0.88), without significant effect of invertebrate exclusion. These findings reflect the divergence in regional variation of deadwood decomposition between pine and oak, which might result from the different sensitivity to microclimate and decomposer invertebrates.

Subject terms: Ecology, Biogeochemistry

Introduction

Deadwoods are significant in forest ecology, given their crucial roles in forest ecosystem functions1. They participate in terrestrial carbon budgets to store dead organic carbon and serve as a carbon dioxide efflux source2–4. The presence and decomposition of deadwoods also stimulate pedogenic processes by differentiating soil humidity from the surrounding areas and incorporating additional organic substrates into the soil5,6. Deadwoods provide feeding sources and microhabitats for soil fauna and flora, and thus, contribute to biodiversity conservation7.

Tracking the controlling factors of decomposition rate is a prioritized topic in deadwood studies. From this traditional perspective, microclimatic conditions dominate deadwood decomposition1. Temperature controls the decomposer communities in deadwoods and the surrounding environments, and strongly mediates the microbial degradation of organic carbon sources into carbon dioxide8,9. Alternatively, moisture is considered a counteracting factor against the stimulating effect of temperature because the deadwood decomposition can be hindered under excessive humidity and drought10,11. Such microclimatic effects can vary with woods' physical and chemical composition, the primary trait for each tree species12. These aspects have enabled forest ecologists to simulate the carbon dynamics using the species-specific average decay constants, modified by the temperature-dependent gradients (e.g., Q10 values) and the moisture functions13,14.

Several studies have reported the importance of uncertainties left behind spatial variations in the deadwood decomposition rate. In particular, Bradford et al.14 suggested that simple modification using microclimate possibly fails to represent local variation in deadwood decomposition due to spatial inconsistency in decomposer abundance, although it can predict the global patterns effectively. Shorohova and Kapitsa15 also reported that the deadwood decomposition could differ throughout European boreal forests because of regional inconsistency in site fertility and tree species as well as microclimatic conditions. Similar spatial variabilities have been detected in microsite levels from landscape-scale studies16–18. The simple aggregation of such variations into an average value may reduce overall accuracy of estimating deadwood dynamics and associated ecosystem processes14. Considering the limited knowledge about deadwood ecology, elucidating the decomposition variability of deadwoods can aid to understanding of forest sciences and efforts to predict forest carbon and nutrient budgets19.

Decomposer invertebrates like termites and beetles may affect the variation in deadwood decomposition20. The colonization of wood decomposing invertebrates potentially creates hot-spots showing a faster decomposition rate relative to the area without such species20,21. The invertebrates sometimes distort the climatic gradients in deadwood decomposition rate owing to their tolerance to the excessively harsh conditions for microbial decomposers22. Such effects of invertebrates may interact with the influences of wood species traits and abiotic environments, given the diversity in their feeding and habitat preferences12,23. However, most of these findings have focused chiefly on tropical and subtropical zones24, while the tendencies underlying the other climatic areas were often underrated despite some empirical evidence21,25,26.

The present study aimed at the variation in the deadwood decomposition of Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc.) and sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima Carruth). These tree species are common in both plantations and naturally regenerated forests of the cool and warm temperate climatic zones in Northeast Asia27. The primary hypothesis is that the variation in deadwood decomposition rate would occur across sites depending on the differences in environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, and soils) and decomposer invertebrate activities. This hypothesis was based on the facts that environmental conditions can control the decomposers’ physical (fragmentation) and chemical (respiration) decay processes11,28 and the areas with a high incidence of decomposer invertebrate can feature a relatively fast wood decomposition rate than the other areas20,21. To prove this hypothesis, pine and oak deadwoods were experimentally set to the nine study sites at the three environmentally distinct regions (western, eastern, and southern) in the Republic of Korea (Fig. 1). The mass loss rate of deadwoods was monitored at each study site for 24 months. Moreover, the mesh enclosing treatment was implemented in half of the deadwood samples, which has been broadly used to examine soil invertebrates' contributions to wood decomposition processes8,29–31.

Figure 1.

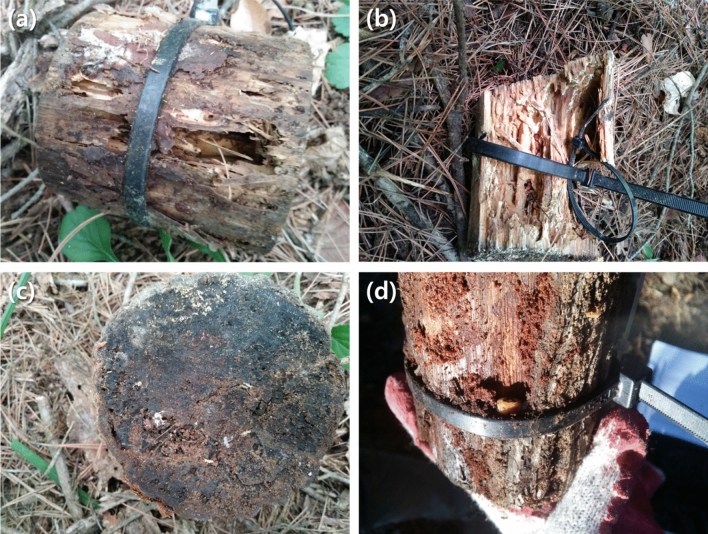

Photographs of the initial deadwood samples in site 1 (a) and site 8 (b) (photograph by Seongjun Kim).

Results

Deadwood decomposition patterns

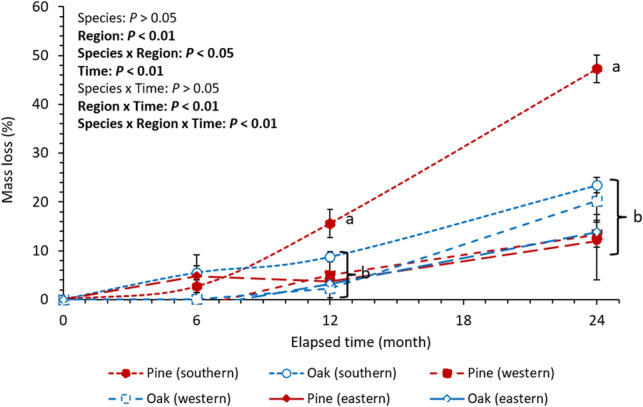

Pine and oak deadwood samples lost, on average, 24.2 ± 4.3% (k = 0.138 ± 0.017 year−1) and 19.1 ± 1.5% (k = 0.106 ± 0.005 year−1) of the initial mass throughout all regions after 24 months. Nevertheless, the mass loss rate was highly variable among regions. Mass loss after 24 months was 47.3 ± 2.8% (k = 0.320 ± 0.027 year−1), 13.3 ± 2.6% (k = 0.071 ± 0.015 year−1), and 11.9 ± 7.9% (k = 0.064 ± 0.045 year−1) for pine, and 23.% ± 1.6% (k = 0.134 ± 0.011 year−1), 20.2 ± 2.8% (k = 0.113 ± 0.018 year−1), and 13.9 ± 2.3% (k = 0.075 ± 0.013 year−1) for oak in the southern, western, and eastern regions, respectively (Fig. 2). The general linear mixed model exhibited that the effects of region and time were significant (P < 0.01), whereas tree species alone had no significant effect on deadwood mass loss (Fig. 2). Significant interaction effects were detected from the combinations of species and region (P < 0.05), region and time (P < 0.01), and species, region, and time (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). The post-hoc test reported that the mass loss of pine deadwoods was significantly higher in the southern region than in the western and eastern regions after 12 and 24 months (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Mass loss of oak deadwoods, however, did not significantly differ among the three regions, even though the average values presented a similar tendency with pine deadwoods (Fig. 2). The difference in mass loss between pine and oak was significant only in the southern region after 12 and 24 months (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mass loss of deadwood samples within the study period (24 months). Letters next to points show statistical differences between the mass losses within a given time (n = 9 for each species within a given region and time, P < 0.05). Vertical bars indicate standard errors.

Deadwood samples exhibited visible damages from invertebrates, including subterranean termites (Fig. 3a–c) and beetles larvae (Fig. 3d). The damage from subterranean termites (Reticulitermes speratus kyushuensis Morimoto) was common and highly intensive in the southern region (Fig. 3a–c), but such pattern did not occur in the western and eastern regions. Though the subterranean termites attacked both tree species in the southern region, pine deadwoods (Fig. 3a, b) received more severe visible damage than oak deadwoods (Fig. 3c). Conversely, the damages from the other decomposer invertebrates (e.g., Neocerambyx raddei Blessig, Tomicus piniperda Linnaeus, Platypus koryoensis Murayama, Scolytoplatypus tycoon Blandford, Dorcus titanus castanicolor Motschulsky, and Dorcus rectus rectus Motschulsky) were not as intensive as those from termites but widespread across tree species and regions (Fig. 3d). As intended, the invertebrate exclusion treatment prevented the access of invertebrates, and no visible invertebrate damage was found on the samples enclosed with mesh during the study period. The invertebrate exclusion effect was negative for all species and study sites, indicating that the exclusion treatment reduced deadwood mass loss in all regions (Table 1). Invertebrate exclusion generally had a greater effect size in the southern region than in the western and eastern regions (Table 1), which was in agreement with the visible damages from subterranean termites.

Figure 3.

Photographs of decomposer invertebrates on deadwood samples. Feeding damages by subterranean termites on pine (a, b) and oak (c) samples, and incidence of beetle larvae (d) after 24 months (photograph by Seongjun Kim).

Table 1.

The invertebrate exclusion effect and invertebrate damage on deadwood samples in each study site.

| Region | Study site | Invertebrate exclusion effecta | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Oak | ||

| Western | Site 1 | 0.42 ± 1.63 | 0.68 ± 1.67 |

| Site 2 | 0.71 ± 1.67 | 1.08 ± 1.77 | |

| Site 3 | 2.23 ± 2.22* | 0.85 ± 1.71 | |

| Eastern | Site 4 | 0.27 ± 1.61 | 4.42 ± 3.46* |

| Site 5 | 0.60 ± 1.65 | 1.34 ± 1.85 | |

| Site 6 | 0.29 ± 1.61 | 0.44 ± 1.63 | |

| Southern | Site 7 | 3.79 ± 3.07* | 1.30 ± 1.84 |

| Site 8 | 4.94 ± 3.78* | 4.74 ± 3.65* | |

| Site 9 | 2.77 ± 2.50* | 2.84 ± 2.54* | |

aEffect size based on Hedges’ d ± 95% confidence interval. Higher value indicates the larger decrease in mass loss of deadwood samples due to the invertebrate exclusion. Values with asterisk are statistically significant at P < 0.05 (the 95% confidence interval did not overlap with zero).

Influential factors for the decomposition rate

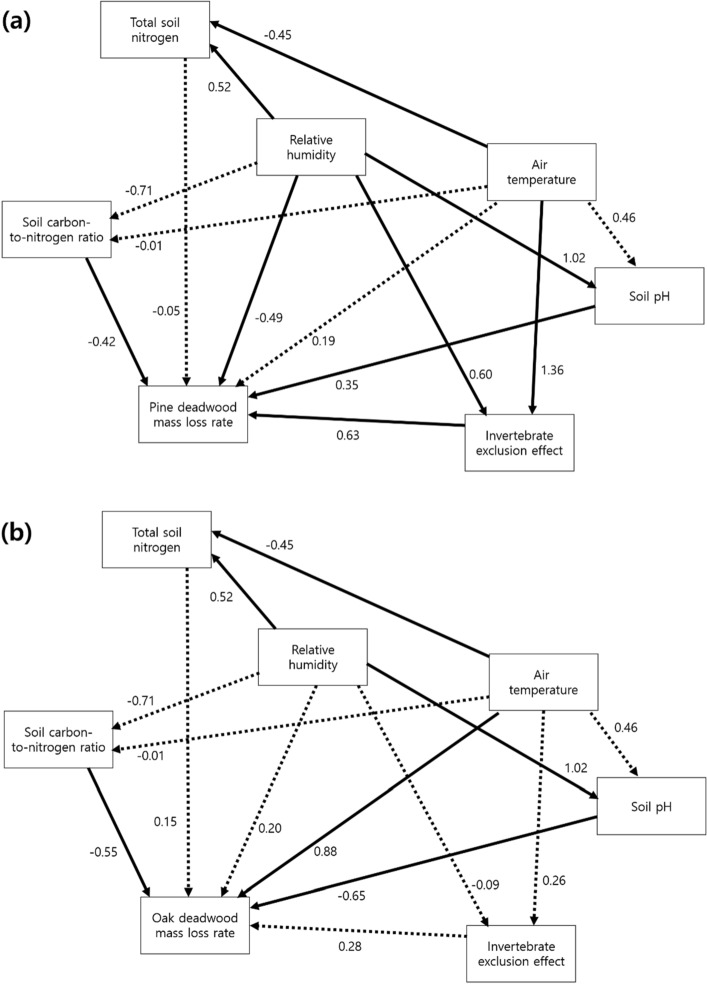

The structural equation model for pine showed that invertebrate exclusion effect was the strongest factor directly affecting the mass loss of pine deadwoods, with a path coefficient of 0.63 (Fig. 4a). Although air temperature had no significant effect on the mass loss of pine deadwoods, it indirectly contributed to the mass loss rate as the strongest influential factor for invertebrate exclusion effect (Fig. 4a). Conversely, the structural equation model for oak demonstrated that air temperature was the strongest factor affecting the mass loss of oak deadwoods, with a path coefficient of 0.88 (Fig. 4b). Invertebrate exclusion effect was not a significant influential factor of the mass loss of oak deadwoods (Fig. 4b), which was on the contrary to the pattern in pine deadwoods.

Figure 4.

Results of structural equation models for the mass loss of pine (a) and oak (b) deadwoods. Values next to each arrow show path coefficients. Straight and dashed arrows indicate significant and non-significant effects at P < 0.05.

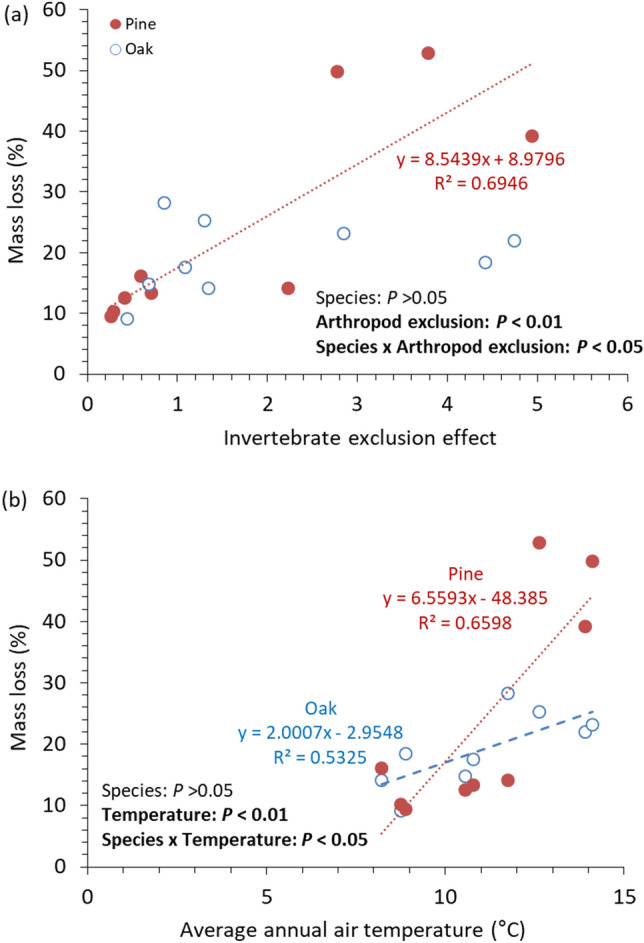

The univariate tests using the strongest influential factors for pine (invertebrate exclusion effect) and oak (air temperature) deadwoods reported that deadwood samples differed in sensitivity to air temperature and invertebrate exclusion (Fig. 5). The analysis of covariance demonstrated significant interaction effects between species and either invertebrate exclusion or air temperature (P < 0.05), and the slopes of the linear regression lines were steeper for pine deadwoods than for oak deadwoods (Fig. 5). These results suggest that oak deadwood decomposition was more tolerant to the gradient of air temperature and decomposer invertebrate activity than pine deadwood decomposition, which possibly led to the relatively low regional variation in the mass loss of oak deadwoods (Fig. 2).

Figure 5.

Relationships of mass loss of deadwood samples after 24 months to invertebrate exclusion effect (a) and average annual air temperature (b). Only significant regression lines are presented on each panel (n = 9, P < 0.05). Dots in each panel represent the average value from three plots within each study site. The higher invertebrate exclusion effect indicates the larger decrease in the mass loss rate of deadwood samples by invertebrate exclusion.

Discussion

The mass loss rate of pine deadwoods was significantly higher in the southern region than in the other regions (P < 0.05, Fig. 2). Results also demonstrate that invertebrate exclusion effect was the most influential factor for the variation in the mass loss of pine deadwoods (Fig. 4a). This pattern agrees with case studies that have reflected the regional difference in pine deadwood decomposition between central (k = 0.086–0.097 year−1)32,33 and southern regions (k = 0.267–0.506 year−1)34. Our results fit into previous studies, emphasizing wood decomposition mechanisms by decomposer invertebrates, including direct feeding and enzymatic digestion, wood structural change owing to tunneling and fragmentation, and biotic interaction with microbial community composition and activity35. Though microbial data were not available in the present study, tunnels and fragmentation by termites prevailed in the southern region only (Fig. 3a–c) as displayed in the invertebrate exclusion experiment by Ulyshen et al.26 for Pinus taeda L. logs. Such concentrated physical damage by decomposer invertebrates in the southern region might contribute to the regional difference in invertebrate exclusion effect (Table 1), and consequently intensify the variation in the mass loss of pine deadwoods as the strongest influential factor (Fig. 4a). This result is similar to Warren and Bradford20, who reported a significant increase in the mass loss of artificial wooden nests at the temperate mixed hardwood forests with termite colonization. Therefore, the results of the present study support the potential role of decomposer invertebrate activity in the spatial variation in temperate pine deadwood decomposition, as indicated in the tropical wet and dry environments17,21,22,36,37.

The mass loss of oak deadwoods, in contrast to pine deadwoods, exhibited only marginal regional variation (Fig. 2) and were unrelated to invertebrate exclusion effect (Figs. 4b, 5a). It was also found that air temperature was the strongest factor directly influencing the mass loss of oak deadwoods, but it was not related to invertebrate exclusion effect for oak (Fig. 4b). These results imply that oak deadwood decomposition might respond to the temperature-related decay mechanism except for an indirect process through decomposer invertebrate activity8. In the present study, oak samples were higher both in initial wood nitrogen concentration (pine: 0.05 ± 0.01%, oak: 0.11 ± 0.00%) and density (pine: 0.4 ± 0.0 g cm−3, oak: 0.6 ± 0.0 g cm−3) than pine samples. Such initial condition of oak deadwoods could be favorable to chemical decomposition by microbes to acquire nitrogen38, rather than invertebrate activity because of dense microfibril arrangement23. This is consistent with an indoor experiment by Yoon et al.39, who reported that microbial respiration from oak deadwoods was higher than that from pine deadwoods, and more sensitive to the surrounding temperature condition. Accordingly, our results indicate that the mass loss of oak deadwoods might correspond to the microbial decomposition level along the air temperature gradient, and be less sensitive to invertebrate activity than pine deadwood decomposition.

It is important to note that air temperature strongly affected invertebrate exclusion effect on pine deadwoods, the strongest influential factor for pine deadwood decomposition (Fig. 4a). Also, air temperature was positively related to the mass loss of pine deadwoods (Fig. 5b), despite no significance in the direct air temperature effect on pine deadwood decomposition (Fig. 4a). Although several studies suggested that the activity of decomposer invertebrate could confound the patterns in deadwood decomposition along a climatic gradient37, such tendency was not detected in the present study. These findings enable us to expect that air temperature might be important for pine deadwood decomposition as an indirect factor controlling decomposer invertebrate activity.

The general linear model revealed that there was a significant difference in regional variation in the mass loss rate between pine and oak deadwoods (interaction effect of region and species, Fig. 2). Mechanisms for such relationship between regional variability and tree species remain unclear due to the limited number of relevant literatures. However, our results show that only the mass loss of pine deadwoods was significantly correlated to the invertebrate exclusion effect (Fig. 5a), and both concentrated termite damage and atypically high mass loss of pine deadwoods occurred in the southern region rather than the western and eastern regions (Fig. 2). This pattern implies that inconsistent sensitivity to decomposer invertebrates possibly led to the different regional variations between pine and oak deadwoods. In fact, the differences in feeding preference are not uncommon in other termite studies12,40,41, and termites’ feeding preferences could intensify the effect of tissue density and recalcitrant compound content on wood decomposition rate23. Furthermore, the detected subterranean termite species, R. speratus kyushuensis is known to prefer P. densiflora than broadleaf tree species as a feeding source because of the difference in wood density and recalcitrant chemical content28. Oak deadwoods used in the present study actually had a higher wood density than pine deadwoods, and thus, could be more tolerant to physical damage by invertebrate decomposers19. Such preferences for pine deadwoods might create a significant difference between the mass losses of pine and oak deadwoods in the southern region accordingly. Inversely, the differential effects on tree species were not notable in the western and eastern regions because of the absence of termite feeding damages and the weaker invertebrate exclusion effect (Table 1), which might cause more distinct regional variation in deadwood decomposition for pine relative to oak. This explanation agrees with the binomial elevation of wood decomposition rate depending on whether Reticulitermes termite colonization exists or not in Warren and Bradford21.

This study’s findings should be carefully interpreted as our study period was limited only for 24 months. Deadwoods are traditionally considered to require an extended period of the decomposition process1. Previous studies have also reported either an increase26 or a decrease40 in the contribution of invertebrates to deadwood decomposition with the time frame. Hence, further monitoring should be followed to ensure if the divergence in the regional variation between pine and oak deadwood decomposition persists in the long term.

Overall results support our primary hypothesis on the regional variation in deadwood decomposition, which was mainly related to invertebrate activity (pine) and air temperature gradient (oak). However, pine deadwoods had a larger regional variation in the mass loss rate than oak deadwoods owing to the concentrated of decomposer invertebrates in the southern region and the higher sensitivity to such decomposer activity. This finding suggests that not only the temperature gradient, but distribution and activity of decomposer invertebrates might reshape the regional variation in deadwood decomposition among multiple temperate forest ecosystems. In terms of forest ecology, decomposing deadwoods are important sources of organic carbon and nutrients, which could result in spatial divergence in quality and fertility of the surrounding soil environments2,5. Therefore, the detected variation among regions and the two species might reflect the associated regional variability of the soil environment as well as tree growth, forest productivity, and carbon dynamics42. The subsequent long term monitoring should be followed to explore such aspect, considering the slow progression of deadwood decomposition.

Methods

Study sites

The present study targeted three environmentally different regions in the Republic of Korea, namely western, eastern, and southern regions (Table 2). The regions had under a temperate climate with a concentrated rainfall during summer and cold, dry winter. However, the southern region featured a warmer microclimate and lower altitude than the other regions, while the eastern region had a colder, moister microclimate and nitrogen rich soils (Table 2). The western region is characterized by an intermediate environment between the southern and eastern regions, although it contained the most acidic soils (Table 2). Such differences in microclimate and soils are expected to differentiate decomposer activity and deadwood mass dynamics across the regions42,43.

Table 2.

Environmental conditions in the study sites in the western, eastern, and southern regions.

| Region | Site | Location | Stand density (stem ha−1) | Altitude (m) | Air temperaturea (°C) | Relative humiditya (%) | Soil pH | Total soil Nb (g kg−1) |

Soil C/N ratiob | Major tree speciesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | Site 1 | 37°47′N, 127°10′E | 650 | 420 | 10.56 | 73.56 | 4.64 | 1.20 | 28.58 | Pinus densiflora, Quercus mongolica, Quercus serrata, Acer pseudosieboldianum |

| Site 2 | 37°46′N, 127°10′E | 1140 | 470 | 10.77 | 73.13 | 4.43 | 1.11 | 30.53 | P. densiflora, Q. mongolica, Q. serrata, A. pseudosieboldianum | |

| Site 3 | 37°44′N, 127°10′E | 2500 | 500 | 11.73 | 75.54 | 4.42 | 1.19 | 26.77 | P. densiflora, Q. serrata, A. pseudosieboldianum | |

| Eastern | Site 4 | 37°30′N, 128°56′E | 610 | 690 | 8.88 | 77.10 | 5.10 | 1.78 | 22.71 | P. densiflora, Quercus aliena, Quercus variabilis, Acer pictum subsp. mono |

| Site 5 | 38°02′N, 128°22′E | 1050 | 610 | 8.21 | 81.73 | 5.17 | 2.49 | 18.93 | P. densiflora, Q. mongolica. Carpinus cordata | |

| Site 6 | 38°03′N, 128°22′E | 900 | 590 | 8.74 | 81.60 | 5.21 | 1.69 | 21.23 | P. densiflora, Q. mongolica. C. cordata | |

| Southern | Site 7 | 35°21′N, 128°10′E | 1200 | 430 | 12.61 | 74.56 | 5.07 | 0.97 | 24.56 | P. densiflora, Q. variabilis, A. pictum subsp. mono, Toxicodendron vernicifluum |

| Site 8 | 35°12′N, 128°10′E | 600 | 170 | 13.90 | 72.83 | 4.77 | 1.02 | 35.42 | P. densiflora, Quercus dentata, Quercus acutissima | |

| Site 9 | 35°12′N, 128°10′E | 1560 | 180 | 14.11 | 71.64 | 4.89 | 0.64 | 23.44 | P. densiflora, Q. dentata, Q. acutissima, T. vernicifluum |

aThe average annual values during the study period (24 months).

bTotal soil N: total soil nitrogen; soil C/N ratio: soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio.

cTree species dominating canopy and sub-canopy layers.

Nine study sites were selected for the deadwood decomposition experiment. Three study sites were included for each region (western region: sites 1–3; eastern region: sites 4–6; southern region: sites 7–9) (Table 2). All study sites were located in the stands with the Korean red pine dominating canopy and broadleaf species (e.g., Quercus spp.) dominating mid-to-understory layers, which is the most common forest type in the country44. Study sites in the same region shared similar average annual air temperature, relative humidity, and soil properties, but differed in stand density (Table 2).

Deadwood decomposition experiments

Deadwoods for the decomposition experiment were collected from a mixed Korean red pine and sawtooth oak stand in Bonghwa, Republic of Korea. All the deadwood samples were thinned and harvested at a single site in March 2016 (2 months before the decomposition experiment) to focus on the regional variation in decomposition rate without heterogeneity in the initial deadwood conditions, such as decay class and soil nutrient, microclimate, and tree composition of the sampling site. The sample trees were also similar in age (20-year-old) and processed into the consistent cylindrical shape to reduce unexpected confounding influences (Fig. 1). Initial dry mass, diameter, length, wood density, carbon concentration, and nitrogen concentration were 361.4 ± 3.5 g, 11.1 ± 0.1 cm, 10.2 ± 0.0 cm, 0.4 ± 0.0 g cm−3, 48.9 ± 0.3%, and 0.05 ± 0.01% for pine deadwood samples and 427.7 ± 5.0 g, 9.4 ± 0.1 cm, 9.9 ± 0.0 cm, 0.6 ± 0.0 g cm−3, 48.4 ± 0.2%, and 0.11 ± 0.00% for oak deadwood samples, respectively. In total, 972 deadwood samples were prepared for each tree species.

Three plots (4 m × 10 m) were established in each study site to clarify the decomposition experiment area (Fig. 1, 27 plots in total). The plots within the same study site had a similar environment (e.g., topography and tree species composition) and were buffered by a 5–10 m wide strip area to avoid uncertainties by spatial distribution. In May 2016, 72 deadwood samples were allocated for each plot (36 samples × 2 tree species), and were fastened horizontally on a slope using strings and cable ties after removing the top litter and humus layer. Half of the deadwood samples were enclosed by a 0.26 mm stainless mesh screen to exclude the access of decomposer invertebrates, such as termites and beetles (Fig. 1). Similar mesh pore sizes have been used by the wood decomposition experiments aiming to eliminate the damage by soil micro- and meso-invertebrates8,18,29–31.

Fresh mass of all deadwood samples without invertebrate exclusion was quantified 6, 12, and 24 months after the plot establishment on each site. One pine and oak deadwood samples were collected from each plot and dried at 85 °C to determine the fresh-to-dry mass ratio. The dry mass of deadwood samples was estimated using fresh mass and fresh-to-dry mass ratio. Mass loss was calculated based on the percentage of decrease in the estimated dry mass relative to the initial dry mass. The decay constant (year−1) during the entire study period was also calculated to ease comparisons with the previous deadwood studies as follows;

Meanwhile, the final dry mass of deadwood samples with invertebrate exclusion was measured after 24 months to analyze the invertebrate exclusion effect (see statistical analyses subsection). Visible damage by invertebrate feeding on the deadwoods was recorded simultaneously.

Environmental data collection

Microclimate data (i.e., air temperature and relative humidity) were monitored every 1 h with an air temperature and humidity sensor (U23-001, Onset, USA) until 24 months after the experiment initiation. A temperature and humidity sensor was installed 30 cm above the soil surface in each study site. Between May and June 2017, mineral soil at 0–10 cm depth was sampled from 15 random locations within each study site, and was incorporated into one composite sample per study site. The soil samples were air-dried and sieved with a 2-mm mesh screen before use for soil analyses. Soil pH was measured under a 1:5 soil-to-water ratio using a refillable electrode (ROSS Ultra pH/ATC Triode, Thermo Scientific Orion, USA). Total soil carbon and nitrogen concentrations were determined using an elemental analyzer to calculate soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (vario Macro, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Germany).

Statistical analyses

The invertebrate exclusion effect on deadwood decomposition was quantified and standardized according to Hedges’ d and a 95% confidence interval45,46, as applied by the wood decomposition experiment of Ulyshen31;

where MLunexcluded and MLexcluded represent the average mass loss of deadwoods without and with invertebrate exclusion after 24 months, and nunexcluded and nexcluded denote the number of plots. Sunexcluded and Sexcluded are standard deviations for the mass loss of deadwoods without and with invertebrate exclusion. The positive invertebrate exclusion effect means the deceleration of the mass loss rate of deadwoods by the invertebrate exclusion. The 95% confidence interval for the invertebrate exclusion effect was estimated as follows45,46;

The general linear mixed model was conducted to compare deadwood mass loss among the tree species and regions along the time frame. This model comprised the fixed effects of tree species and region and the random effects of elapsed time and the study site within a region (block) on the mass loss of deadwood samples. A post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test followed this general linear mixed model, and a plot within each study site was used as the unit of replication (n = 9 for each tree species in each region at a given time frame; P < 0.05). The values were log-transformed for this analysis to achieve the normality criteria. The general linear mixed model was conducted with the proc glimmix procedure in SAS v.9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., USA).

Structural equation model was applied to summarize the contribution of controlling factors to the deadwood mass loss. Here, microclimate (air temperature and relative humidity), soil conditions (soil pH, total soil nitrogen, and soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio), and decomposer invertebrate activity (invertebrate exclusion effect) were set to affect deadwood mass loss rate. It was also assumed that microclimate influenced soil conditions and decomposer invertebrate activity. The fitness of the structural equation models was confirmed based on a chi-squared test (P > 0.05) and comparative fit index (> 0.90). Z-transformation was used for normalization of all variables. The structural equation models were conducted with the Lavaan package in R v.4.0.3 software (R Core Team, 2020).

Analysis of covariance and linear regression tests were implemented to show the univariate relationship between deadwood mass loss and the major controlling factors for each tree species (n = 9 for each tree species; P < 0.05). This analysis especially focused on the factors that had the highest path coefficient for either pine or oak deadwood mass loss in the structural equation model. The analysis of covariance and linear regression were conducted with the proc glimmix procedure in SAS v.9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., USA).

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the research grant of the National Research Foundation of the Republic of Korea (NRF2018R1A2B6001012, 2015R1D1A1A01057124). The authors gratefully thank the assistances from Jongyeol Lee, Hanna Chang, Jiae An, Hyungsub Kim, Gwangeun Kim, Jusub Kim, Sohye Lee, and Minji Park, and Jisoo Kim of Ecosystem Ecology Laboratory of Korea University during the field measurements and wood sample preparation. Prof. Choonsig Kim of Gyeongnam National University of Science and Technology helped select and establish the sites in southern region.

Author contributions

S.K. conceptualized the topic and methodology of the present study, led the deadwood decomposition experiment, and data processing and analysis, and wrote the original draft. S.H.H., G.L., Y.R., and H.J.K. participated in the field investigation and review and editing of the draft. Y.S. contributed to the study conceptualization and supervised overall processes, including funding acquisition, project administration, validation, and review and editing of the draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harmon ME, et al. Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1986;15:133–302. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60121-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagomarsino A, et al. Decomposition of black pine (Pinus nigra J. F. Arnold) deadwood and its impact on forest soil components. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:142039. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnússon RÍ, Tietema A, Cornelissen JHC, Hefting MM, Kalbitz K. Tamm review: Sequestration of carbon from coarse woody debris in forest soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016;377:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.06.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt K. Carbon budgets of temperate forest ecosystems. Tree Physiol. 1991;9:69–86. doi: 10.1093/treephys/9.1-2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stutz KP, Lang F. Potentials and unknowns in managing coarse woody debris for soil functioning. Forests. 2017;8:37. doi: 10.3390/f8020037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulyshen MD, et al. Below- and above-ground effects of deadwood and termites in plantation forests. Ecosphere. 2017;8:e01910. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siitonen J. Ecology of woody debris in boreal forests. Ecol. Bull. 2001;49:11–41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietsch KA, et al. Wood decomposition is more strongly controlled by temperature than by tree species and decomposer diversity in highly species rich subtropical forests. Oikos. 2019;128:701–715. doi: 10.1111/oik.04879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein MA, Crowther TW, Maynard DS, Schilling JS, Bradford MA. Decoupling direct and indirect effects of temperature on decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017;112:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Z, et al. Traits mediate drought effects on wood carbon fluxes. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020;26:3429–3442. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon TK, Noh NJ, Kim S, Han S, Son Y. Coarse woody debris respiration of Japanese red pine forests in Korea: controlling factors and contribution to the ecosystem carbon cycle. Ecol. Res. 2015;30:723–734. doi: 10.1007/s11284-015-1275-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu D, Pietsch KA, Staab M, Yu M. Wood identity alters dominant factors driving fine wood decomposition along a tree diversity gradient in subtropical plantation forests. Biotropica. 2021;53:643–657. doi: 10.1111/btp.12906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohtsuka T, et al. Role of coarse woody debris in the carbon cycle of Takayama forest, central Japan. Ecol. Res. 2014;29:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s11284-013-1102-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford MA, et al. Climate fails to predict wood decomposition at regional scales. Nat. Clim. Change. 2014;4:625–630. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shorohova E, Kapitsa E. Influence of the substrate and ecosystem attributes on the decomposition rates of coarse woody debris in European boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014;315:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crockatt ME, Bebber DP. Edge effects on moisture reduce wood decomposition rate in a temperate forest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015;21:698–707. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dossa GGO, et al. Quantifying the factors affecting wood decomposition across a tropical forest disturbance gradient. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020;468:118166. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichenberg D, et al. The effect of microclimate on wood decay is indirectly altered by tree species diversity in a litterbag study. J. Plant Ecol. 2017;10:170–178. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtw116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornwell WK, et al. Plant traits and wood fates across the globe: Rotted, burned, or consumed? Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009;15:2431–2449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01916.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren RJ, Bradford MA. Ant colonization and coarse woody debris decomposition in temperate forests. Insect Soc. 2012;59:215–221. doi: 10.1007/s00040-011-0208-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acanakwo EF, Sheil D, Moe SR. Wood decomposition is more rapid on than off termite mounds in an African savanna. Ecosphere. 2019;10:e02554. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veldhuis MP, Laso FJ, Olff H, Berg MP. Termites promote resistance of decomposition to spatiotemporal variability in rainfall. Ecology. 2017;98:467–477. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu G, et al. Termites amplify the effects of wood traits on decomposition rates among multiple bamboo and dicot woody species. J. Ecol. 2015;103:1214–1223. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maynard DS, Crowther TW, King JR, Warren RJ, Bradford MA. Temperate forest termites: ecology, biogeography, and ecosystem impacts. Ecol. Entomol. 2015;40:199–210. doi: 10.1111/een.12185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsen RM, Sverdrup-Thygeson A, Kauserud H, Mundra S, Birkemoe T. Exclusion of invertebrates influences saprotrophic fungal community and wood decay rate in an experimental field study. Funct. Ecol. 2018;32:2571–2582. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulyshen MD, Wagner TL, Mulrooney JE. Contrasting effects of insect exclusion on wood loss in a temperate forest. Ecosphere. 2014;5:47. doi: 10.1890/ES13-00365.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Box EO, Fujiwara K. A comparative look at bioclimatic zonation, vegetation types, tree taxa and species richness in northeast Asia. Bot. Pac. 2012;1:5–20. doi: 10.17581/bp.2012.01102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee K-S, Jeong S-Y. Ecological characteristics of termite (Riticulitermes speratus kyshuensis) for preservation of wooden cultural heritage. Conserv. Stud. 2004;37:327–348. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheesman AW, Cernusak LA, Zanne AE. Relative roles of termites and saprotrophic microbes as drivers of wood decay: A wood block test. Austral Ecol. 2018;43:257–267. doi: 10.1111/aec.12561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoklosa AM, et al. Effects of mesh bag enclosure and termites on fine woody debris decomposition in a subtropical forest. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2016;17:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2016.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulyshen MD. Interacting effects of insects and flooding on wood decomposition. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e101867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noh NJ, et al. Carbon and nitrogen accumulation and decomposition from coarse woody debris in a naturally regenerated Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora S. et Z.) forest. Forests. 2017;8:214. doi: 10.3390/f8060214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon TK, et al. Coarse woody debris mass dynamics in temperate natural forests of Mt. Jumbong, Korea. J. Ecol. Field Biol. 2011;34:115–125. doi: 10.5141/JEFB.2011.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park S-W, Baek G, Byeon H-S, Kim YS, Kim C. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics of wood stakes as affected by soil amendment treatments in a post-fire restoration area. Korean J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018;20:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulyshen MD. Wood decomposition as influenced by invertebrates. Biol. Rev. 2016;91:70–85. doi: 10.1111/brv.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentry JB, Whitford WG. The relationship between wood litter infall and relative abundance and feeding activity of subterranean termites Reticulitermes spp. in three southeastern coastal plain habitats. Oecologia. 1982;54:63–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00541109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuurman G. Decomposition rates and termite assemblage composition in semiarid Africa. Ecology. 2005;86:1236–1249. doi: 10.1890/03-0570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weedon JT, et al. Global meta-analysis of wood decomposition rates: A role for trait variation among tree species? Ecol. Lett. 2009;12:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon TK, et al. Effects of sample size and temperature on coarse woody debris respiration from Quercus variabilis logs. J. For. Res. 2014;19:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s10310-013-0412-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roh Y, et al. Changes in the contribution of termites to mass loss of dead wood among three tree species during 23 months in a lowland tropical rainforest. Sociobiology. 2018;65:59–66. doi: 10.13102/sociobiology.v65i1.1838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vasconcellos A, de Moura FMS. Wood litter consumption by three species of Nasutitermes termites in an area of the Atlantic coastal forest in northeastern Brazil. J. Insect Sci. 2010;10:72. doi: 10.1673/031.010.7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, et al. Differential effects of coarse woody debris on microbial and soil properties in Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc. forests. Forests. 2017;8:292. doi: 10.3390/f8080292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim R-H, et al. Coarse woody debris mass and nutrients in forest ecosystems of Korea. Ecol. Res. 2006;21:819–827. doi: 10.1007/s11284-006-0034-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korea Forest Service. Statistical Yearbook of Forestry. Korea Forest Service, Daejeon (2020) (in Korean)

- 45.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2007;82:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]