Abstract

Since Skinner’s conceptualization of the mand, applied behavior analysis researchers have used the concept to develop stimulus control transfer procedures effective for addressing manding deficits. More recently, researchers have explored the clinical utility of reinforcing mand variability during mand training and functional communication training. However, limitations in the conceptual analysis of mand variability may have limited the kinds of questions addressed in this research and our understanding of the findings. The current article reconceptualizes mand variability as consisting of eight distinct dimensions and provides operational definitions of the dimensions that may be useful for more precisely characterizing the effects of reinforcement on mand variability in future research. The article concludes with a brief discussion of potential clinical and research implications.

Keywords: Manding, Lag schedules, Variability, Mand training

Within a selectionist framework (Skinner, 1981), variability is fundamental to the development of behavioral repertoires (Palmer, 2012). Operant variability is adaptive to the extent that behaving variably helps the organism maximize reinforcement and avoid aversive stimulation when contingencies change (e.g., Sidman, 1960). So, verbal operant variability should play a fundamental role in the development of verbal repertoires through operant and cultural selection (Greer, 2008). Operant variability can be controlled with reinforcement (Page & Neuringer, 1985). Accordingly, some researchers have suggested that reinforcing operant variability, such as mand variability, may produce clinically important outcomes in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013)—for example, in a general sense by addressing the repetitive and stereotyped behavior (i.e., invariance problems; Rodriguez & Thompson, 2015; Silbaugh et al., 2016) characteristic of the disorder, or in specific applications such as programming for the persistence of manding during challenges to treatment following functional communication training (FCT; e.g., Bloom & Lambert, 2015; Falcomata & Wacker, 2012). The predominant reinforcement schedule used in applied research for this purpose is the lag schedule. Lag schedules deliver reinforcement contingent on responding that varies along a target dimension. Specifically, under a lag schedule of reinforcement, a response or response sequence is reinforced if it differs from N prior responses, with N equal to the value of the lag schedule. For example, under a Lag 1 schedule of reinforcement for socially appropriate responses to social questions by individuals with ASD, researchers reinforced responses to social questions that were appropriate and different from the response evoked in the preceding trial (Lee et al., 2002). In the current conceptual analysis, I will try to argue persuasively that a new conceptual analysis of the precise dimensions along which a target verbal operant such as the mand can “differ” is critical for advancing our understanding of reinforced verbal variability.

Reinforcing Mand Variability

The mand is a verbal operant “in which the response is reinforced by a characteristic consequence and therefore is under the functional control of relevant conditions of deprivation or aversive stimulation” (Skinner, 1957, pp. 35–36). The form of the response often specifies the characteristic consequence. Mands are under the control of two general types of motivating operations (Michael, 1988): establishing operations (EOs) and abolishing operations (AOs; e.g., Miguel, 2013). An EO for reinforcement in relation to manding is any antecedent stimulus, operation, or condition that momentarily increases dimensional quantities (e.g., rate, latency) and variability in the mand, and increases the value or effectiveness of reinforcers produced by the mand. An AO for reinforcement has the opposite dimension- and value-altering effects. For example, when deprived of money (EO), we may be more likely to ask (response) a friend for money, and receiving money (consequence) from the friend will more effectively reinforce that response under such circumstances (EO) relative to other circumstances such as just having won a lottery (AO). Manding, like other verbal operants, can be vocal or nonvocal (Skinner, 1957). The concepts of the mand and other verbal operants (e.g., tact, intraverbal) provide the framework for many highly effective strategies such as mand training used by multiple disciplines to address verbal delays and deficits in individuals with disabilities (e.g., Sundberg & Partington, 1998).

Over the past decade, researchers have started to develop procedures (e.g., lag schedules) that increase mand variability during mand training. Silbaugh, Murray, et al. (2020) conducted a systematic synthesis of research on lag schedules in humans. In their synthesis they identified multiple studies that evaluated the effects of lag schedules on mand variability specifically. Characteristics of those studies, as well as a study by Carr and Kologinsky (1983) that arranged a contingency that reinforced mand variability but did not use a lag schedule of reinforcement, are summarized in Table 1. The findings from those studies converge to suggest that (a) participants were mostly children and adolescents with ASD, (b) the most common dependent variable was the rate of mand variability, (c) lag values ranged from Lag 1 to Lag 5, (d) studies targeted vocal and nonvocal (i.e., selection-based or sign manding) mand variability, (e) lag schedules can increase novel manding, (f) lag schedules may establish or expand mand response class hierarchies, (g) individuals with language delays or deficits receiving mand training with or without FCT can vary their manding across vocal and nonvocal modalities under contingencies selective for variability, and (h) lag schedules can reinforce mand variability within the context of manualized social skills treatment packages for children with ASD.

Table 1.

Summary of applied experiments on the reinforcement of mand variability

| Authors | Participants | Dependent variables | Independent variables | Modalities | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adami et al. (2017) | 2 males with ASD, ages 10 and 23 years | Responses per minute of variant manding | Lag 1 / FCT | Nonvocal selection-based and vocal | Lag 1 / FCT increased variant manding and decreased challenging behavior. |

| Brodhead et al. (2016) | 3 males with ASD, ages 4–5 years | Number of different mand frames | Lag 2 and Lag 3 with and without other components | Vocal topography based | Discriminated variability in mand frames was exhibited and maintained with lag schedules. |

| Carr and Kologinsky (1983), Experiment 1 | 3 males with ASD, ages 9–14 years | Number of different signs | Within sessions, “the adult reinforced only the first two instances of a given sign; additional instances were ignored” (p. 300) | Nonvocal topography based (i.e., sign) | Relative to baseline extinction of manding, sign manding was variable. |

| Falcomata et al. (2018) | 2 males with ASD, ages 8 & 10 years | Responses per minute of variant manding and challenging behavior | Lag 1 / FCT through Lag 5 / FCT | Nonvocal selection based and vocal | Lag 1 / FCT through Lag 5 / FCT increased variant manding and decreased challenging behavior. |

| Ferguson et al. (2019) | 2 males and 2 females with ASD, ages 3–13 years | Percentage of trials with variant manding | Lag 1 with a small or large magnitude (i.e., 1 or 4 edibles) | Nonvocal selection based | Larger magnitudes of reinforcement associated with the lag schedule produced relatively more variant manding. |

| Radley et al. (2017) | 1 male and 2 females with ASD, ages 5–7 years | Cumulative appropriate and variable responses (i.e., mands and other verbal operants) | Lag 2 with other components of a manualized social skills program | Vocal topography based | Lag schedules combined with supplemental visual stimuli increased appropriate and variable responding. |

| Radley et al. (2018) | 2 males and 1 female with ASD, ages 11 & 12 years | Number of appropriate and variable responses per session (i.e., mands and other verbal operants) and cumulative appropriate and variable responses per session | Lag 1–5 with other components of a manualized social skills program | Vocal topography based | Lag schedules increased appropriate and variable responding. |

| Radley et al. (2020) | 3 males with ASD, ages 11–12 years | Number of cumulative novel responses | Lag 2 with other components of a manualized social skills program | Vocal topography based | Lag schedules increased variable responding as indicated by novel responding. |

| Silbaugh et al. (2018) | 1 male and 1 female with ASD, ages 3–4 years | Responses per minute of prompted variant, independent variant, and independent invariant manding | Lag 1 plus progressive time delay | Vocal topography based | Lag 1 plus progressive time delay increased independent topographical vocal mand variability and expanded mand response class hierarchies. |

| Silbaugh and Falcomata (2019) | 1 male with ASD, age 5 years | Responses per minute of prompted variant, independent variant, and independent invariant manding | Lag 1 plus progressive time delay | Nonvocal topography based (i.e., sign) | Lag 1 plus progressive time delay established a mand response class hierarchy and increased independent nonvocal topography-based mand variability. |

| Silbaugh, Swinnea, and Falcomata (2020) | 4 males with ASD, ages 4–5 years | Responses per minute of independent variant, independent invariant, prompted variant, and total independent manding, and challenging behavior | FCT with Lag 1 plus progressive time delay; FCT with Lag 1 plus least-to-most prompting; FCT with Lag 1 | Vocal topography based | Increased independent variant vocal mand variability coincided with the Lag 1 schedule. |

Note. With the exception of Carr and Kologinsky (1983), this table of studies is based on the mand variability studies identified in a comprehensive systematic synthesis of human lag schedule research conducted in humans (Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020). Carr and Kologinsky (1983) arranged a contingency that increased mand variability but did not use a lag schedule of reinforcement. ASD autism spectrum disorder, FCT functional communication training

Despite those promising findings, this area of research is in its infancy and therefore warrants careful skepticism about the effects of mand variability training with lag schedules on adaptive behavior, language development, and related long-term outcomes. For example, researchers have yet to demonstrate the use of mand variability training used to target adaptive mand variability, as indicated by a lack of studies examining whether reinforced mand variability increases participants’ contact with reinforcement and avoidance of aversive stimulation when contingencies change in naturally occurring contexts where mand invariance was a clinically significant problem (Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020). Little is known about the effects, generality, maintenance, social validity, and social significance of behavioral interventions such as lag schedules that increase variability in verbal and nonverbal behavior (e.g., Rodriguez & Thompson, 2015; Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020; Wolfe et al., 2014; Wolfe et al., 2019). Furthermore, no studies have examined the effects of reinforced verbal variability on language development (i.e., longitudinal studies; Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020). The extent to which we can adequately address some of these questions in future research may hinge on how we conceptualize mand variability and the kinds of contingencies we arrange to reinforce it.

The Need for Further Conceptual Analysis of Mand Variability

By drawing attention to some easily overlooked nuances of the contingencies programmed in existing mand variability research, behavior analysts may see gaps in our understanding of exactly what happens to mand variability when we reinforce it (e.g., Brodhead et al., 2016; Falcomata et al., 2018), as well as concurrent reinforcement schedule arrangements in which there are no programmed contingencies for mand variability but mand variability nevertheless increases (e.g., Bernstein & Sturmey, 2008).

Falcomata et al. (2018) evaluated the effect of lag schedules on mand variability and challenging behavior across a series of increases in variability requirements during FCT in children with ASD. This study was important because it demonstrated that increasing variability requirements over time with mand variability training during FCT increased the use of multiple mand modalities without appreciable increases in challenging behavior. Following functional analyses and mand modality assessments, the researchers conducted baseline FCT sessions in which they reinforced challenging behavior on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement and placed manding on extinction. During baseline, no mand modalities (i.e., iPad with Proloquo2Go, iPhone, picture card, word card, and microswitch) were present. During FCT conditions with and without lag schedules, mand modalities were present. During FCT without lag schedules, the researchers delivered reinforcement for mands with the modalities (e.g., exchanging a picture card) regardless of which of the concurrently available mand modalities they used. During FCT with lag schedules, again the multiple mand modalities were concurrently available, but the researchers delivered reinforcement contingent on selecting a mand modality that differed from N preceding mand modality selections within sessions, with N equal to the value of the lag schedule (Lag 1–5; i.e., variability requirements). An exception, however, was that the researchers also reinforced vocal variant mands (i.e., asking for the reinforcer instead of selecting one of the nonvocal selection-based modalities) for participant Petyr. As I will discuss in what follows, varying across selection-based modalities, and varying across topography-based and selection-based modalities, may represent different mand variability dimensions that may be differentially affected by contingencies arranged for either or both. Because the researchers measured variant manding overall, specifically which dimensions of mand variability were strengthened or weakened by the contingency are unknown. However, readers may find it interesting to note that when variability requirements were low (i.e., low lag schedule value), vocal manding was infrequent, but when variability requirements were high (i.e., higher lag schedule values), vocal manding increased. This finding suggests that perhaps mand variability training in which a practitioner strategically manipulates lag schedule values and targets specific aspects of mand variability may help to increase vocal manding in otherwise minimally vocal individuals.

Bernstein and Sturmey (2008) used a reversal design across continuous and intermittent schedules of reinforcement of high-rate mands to evaluate the effects of the latter on mand variability. The participants were two children with ASD, and the study was conducted in a school setting. The dependent variable pertaining to variability was the number of alternate mands emitted per session. In baseline and treatment, multiple reinforcers were concurrently available. During baseline, the researchers reinforced all mands on an FR1 schedule. During treatment, the researchers reinforced a single, high-rate mand on an FR10 schedule (or FR25 for Jake) and other mands on an FR1 schedule. Critically, the participants used both vocal and picture-exchange mand modalities, and mands in both modalities were reinforced. However, the researchers did not measure variant manding in terms of switching between topography-based and selection-based responding, but rather variability across mands (i.e., across reinforcers). One participant (Jake) manded at higher rates overall during FR1/FR10 and FR1/FR25 conditions relative to FR1-only conditions. However, across-mand variability (i.e., “alternate mands emitted”) was higher for both participants under FR1/FR10 or FR1/FR25 conditions relative to FR1 only. These findings suggested that placing a previously high-rate mand on a relatively thin intermittent schedule of reinforcement in the presence of continuously reinforced alternative mands can increase across-mand variability. Yet, because the researchers did not distinguish between different dimensions of mand variability (e.g., topography-based variability, selection-based variability, or a combination), we cannot distinguish between the effects of the independent variable on across-mand (i.e., different reinforcers), across-modality (i.e., vocal and picture exchange), topographical (i.e., vocalize vs. reach, hold, and exchange picture), or selection-based (i.e., picture exchange) mand variability.

Brodhead et al. (2016) evaluated the effects of lag schedules on mand frame variability in children with ASD in the presence of multiple concurrently available preferred edibles. A mand frame (e.g., “I want . . . ,” “Can I have . . . ?”) was “an instance in which the participant emitted a vocal response that included a subject, verb, and noun that corresponded to an available edible item” (p. 37). Mand frame variability was assessed by measuring “different mand frames.” A mand frame was different if it “differed by more than the researcher’s name, nouns that corresponded to available edible items, rearranging the word order, specifying a number or color of an edible item, or adding or deleting the word ‘please.’” (p. 37). The researchers also examined script training and fading and discriminative stimulus control over mand frame variability, but those features are not relevant to the current discussion. During the Lag 2 schedule, a mand frame was reinforced if it differed from the previous two mand frames emitted in the session. Lag schedules increased the number of different mand frames emitted. However, due to the operational definition of different mand frames and the concurrent availability of multiple reinforcers within sessions, it is unclear whether lag schedules reinforced topographical variability within mands (e.g., saying “I want . . . ,” then “Can I have . . . ?” in a session for the same reinforcer), topographical variability across mands (e.g., saying “I want . . .” for one reinforcer, then saying “Can I have . . . ?” for a different reinforcer), or both of these, as well as implications of those different contingencies.

In summary, these and other studies on mand variability in individuals with ASD have expanded our understanding of the phenomenon. Yet this small representative sample suggests that how researchers (including this author) have conceptualized mand variability and arranged corresponding contingencies may have inadvertently masked potentially important and interesting effects of contingencies on mand variability in this population. Perhaps even more importantly, no studies have examined the effects of reinforced mand variability in individuals with typical language (Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020), thereby significantly limiting our ability to understand which effects of reinforced mand variability are applicable generally to manding, or specific to manding in individuals with the kinds of verbal deficits and delays common in ASD. Thus, further conceptual analyses of mand variability that expand the range of questions we ask about reinforced variability in individuals with typical language and those with verbal delays and deficits may have important implications for clinical outcomes and advance our understanding of the variables that control manding generally.

Next, I define and describe two general types of speaker responses (selection based and topography based) and two general listener behaviors (manded stimulus selection and manded compliance), as conceptualized by Jack Michael (2004). Then I distinguish between mand variability across mands and within mands. Then, I propose and provide examples of eight potential dimensions of mand variability, each of which may serve as a distinct dependent variable in studies on the reinforcement of mand variability. Throughout this analysis, I discuss some implications of the current conceptualization of mand variability for future research and practice.

Selection-Based and Topography-Based Manding

Based on Jack Michael’s (2004) conceptualization of selection-based and topography-based speaker responses, we can identify two overarching categories of mand variability: selection based and topography based. Selection-based mands alter the probability of listener-mediated reinforcement by selecting a stimulus in the environment. The topography is constant across a range of stimuli, but stimulus selection varies. The listener provides different reinforcers depending on the stimuli selected by the speaker. For example, a nonvocal child may give someone a picture of a ball in exchange for a ball to play with, or the same child may give a picture of a car in exchange for a toy car. The topography of the card exchange can be classified as invariant (e.g., always a reach, grasp, and handoff with the right hand) if our concern in this scenario is with card exchange responses, not subtle variations in muscle movements, which may only be reliably and accurately detected with technology. That is, classifying card exchange as an invariant response despite slight variations in perhaps the trajectory of the reach or other subtle variations in motion or force can be sufficient to enable experimental analyses aimed at distinguishing between these types of speaker responses. Critically, with topographically invariant selection-based manding, picture selections vary, and the listener provides a different reinforcer (e.g., toy ball or toy car) based on the picture selected. Characteristics of selection-based responding that distinguish it from topography-based responding include (a) the speaker is presented with one or more stimuli, the evocative effects of which are controlled by the relevant EO; (b) a conditional discrimination repertoire is required; (c) a scanning repertoire is required when multiple stimuli are concurrently available; (d) the selection response is usually already part of the learner’s repertoire; (e) there is no point-to-point correspondence between the response and response-produced stimuli that affect listener behavior; (f) some environmental arrangements are necessary (i.e., stimulus presentation); and (g) stimulus control over responding may be weakened as the stimulus array increases in size (Potter & Brown, 1997).

In contrast, topography-based mands alter the probability of listener-mediated reinforcement by varying the form of the response. In the pure form of this kind of manding, the topography varies across instances, and no stimuli are selected, such as signing “ball” and receiving a ball, then saying “car” and receiving a toy car. As a result of the speaker varying responses topographically, the listener provides different reinforcers. Characteristics of topography-based responding that distinguish it from selection-based responding include (a) the response is evoked by an EO independent of a stimulus array, (b) responses are formally distinguishable from one another, (c) a scanning repertoire or conditional discriminations with respect to antecedent stimulus arrays are not required, (d) there is point-to-point correspondence between the response and response-produced stimulus that controls the listener’s behavior, and (e) no material preparation is required (Potter & Brown, 1997).

Manded Stimulus Selection and Manded Compliance

Listeners reinforce mands through manded stimulus selection or manded compliance (Michael, 2004). When a listener reinforces a speaker’s mand by selecting a named stimulus (e.g., a speaker says “pass the mustard” and the listener gives the speaker the mustard bottle), we call the listener’s behavior manded stimulus selection. When a listener reinforces a speaker’s mand by engaging in behavior specified by the mand (e.g., a speaker says “stop, that’s enough, thanks” and the listener stops applying the mustard to the sandwich), we call the listener’s behavior manded compliance. As such, topographical or stimulus selection-based mand variations alter the current probability (i.e., evoke or abate) that the listener will deliver a given reinforcer through compliance or manded stimulus selection depending on the current reinforcement contingencies.

This logic suggests that mand variations alter the current probability that the same reinforcer will be delivered in a context in which the reinforcer delivered for a prior response was withheld, such as when (a) the probability of the listener delivering the reinforcer is low due to contingencies competing for the listener’s behavior (e.g., the listener is on a phone call), (b) stimulus control over manded stimulus selection or manded compliance by the listener is weak, or (c) the listener reinforces manding contingent on manding differently (i.e., a naturally occurring schedule of reinforcement for mand variability). The probability the listener will mediate reinforcement for the mand can also depend on the specific topography (e.g., saying the Polish word for help, “wsparcie,” will have a different effect on a non-English-speaking Polish listener compared to the English word “help”) or stimulus selection (e.g., a specific picture icon selected by a nonvocal individual with ASD) emitted by the speaker. In such cases, manding is adaptive to the extent that it varies sufficiently to evoke listener-mediated reinforcement. For example, in clinical contexts in which FCT is applied to treat challenging behavior in children with ASD, challenging behavior can recur when invariant vocal manding reinforced on a continuous schedule of reinforcement contacts a lag schedule of reinforcement (Silbaugh, Swinnea, & Falcomata, 2020, Figs. 2 and 4). Within this context, we might think of adaptive mand variability as the extent to which the speaker emits socially appropriate mand variations without challenging behavior over time as contingencies for manding change. Adaptive mand variability would consist of highly proficient mand variability without challenging behavior, and maladaptive mand variability would consist of continued invariant manding (despite the contingency change) and the recurrence of challenging behavior, to the extent that the former, relative to the latter, maximizes reinforcement and minimizes aversive stimulation.

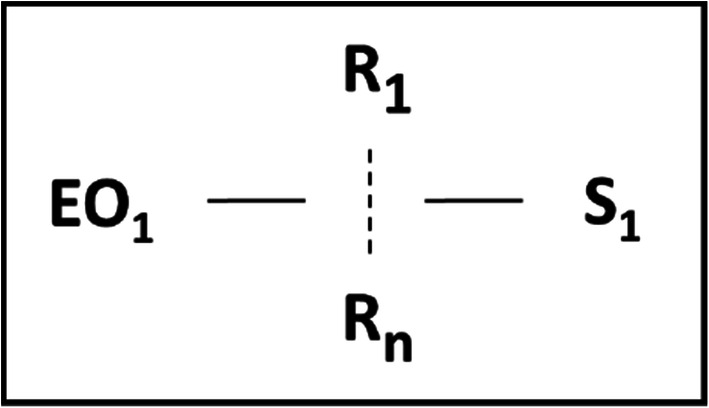

Fig. 2.

Contingency diagram of topography-based within-mand variability. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variation in response topographies. EO = establishing operation; R = response topography; S = reinforcer

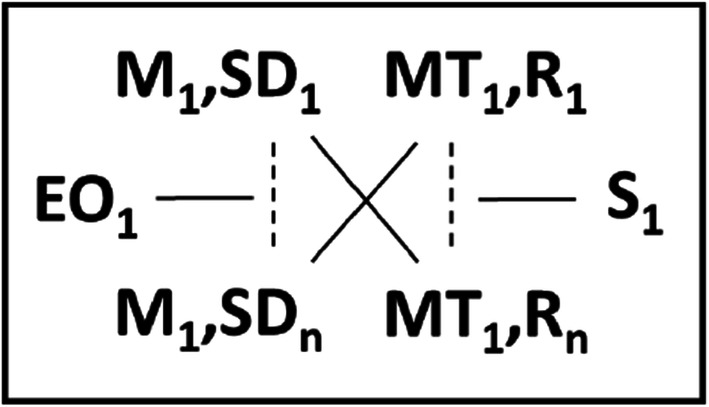

Fig. 4.

Contingency diagram of selection-based mand variability. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variation in selection-based modality. EO = establishing operation; M = selection-based modality; R = response; S = reinforcer

Across- and Within-Mand Variability

Manding can vary within a mand or across mands (Silbaugh & Falcomata, 2019). Manding across mands is the emission of mands for different reinforcers over time. A contingency diagram of across-mand variability is displayed in Fig. 1. Studies that examine across-mand variability present participants with multiple reinforcers in a concurrent schedule arrangement (e.g., Brodhead et al., 2016). Types of across-mand variability are beyond the scope of this article. Manding can also vary within a mand, meaning a mand may consist of a functional response class and instances of the mand over time may vary across members of the response class. Effective programming for adaptive manding in individuals with delayed or impaired manding repertoires may benefit from assessing and selectively targeting deficiencies along one or more specific dimensions of mand variability inherent to common manding-intervention contexts. Theoretically, selectively targeting one or more dimensions of mand variability relative to others, or selectively targeting a particular combination of mand variability dimensions, may be more or less effective at strengthening a deficient manding repertoire. In other words, the mand variability dimension targeted by a practitioner, advertently or inadvertently, might determine the effectiveness of manding interventions and in some cases determine whether a learner acquires a vocal or nonvocal manding repertoire.

Fig. 1.

Contingency diagram of across-mand variability. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. EO = establishing operation (the diagram depicts three different EOs); R = response; S = reinforcer (the diagram depicts three different mands)

Dimensions of Within-Mand Variability

Eight hypothesized dimensions of within-mand variability, the primary topic of this article, are the following: (a) across vocal topographies, (b) across nonvocal topographies, (c) a combination of across topographies and across topographical modalities, (d) across nonvocal selection-based modalities, (e) a combination of across topographies and across selection-based modalities, (f) across stimuli within a selection-based modality, (g) a combination of across topographies and across stimuli, and (h) across nonvocal topographies and across selection-based modalities.

Topography-Based Within-Mand Variability

A contingency diagram of emitted topography-based within-mand variability is displayed in Fig. 2. A mand is maintained and therefore defined by a specific form of reinforcement (Skinner, 1957). A request for juice is one mand, and a request for milk is another mand. When one mands for juice and then mands for milk, two mands have occurred. Thus, if one asked for juice three times in a day, it would be incorrect to say that three mands occurred. Rather, each request for juice would be counted as an instance of a single mand for juice (i.e., three instances of one mand). Topographically variant within-mand variability consists of exhibiting a different response form or structure across instances of a single mand. For example, while access to a video is temporarily withheld, a child might emit “play,” “watch,” or “movie” until a response is reinforced (Silbaugh et al., 2018). No precision is lost when talking about variability in the topography of a behavior by using descriptions such as “topographical variability,” “variant topographies,” “topographically variant,” or “variant responding,” particularly when one specifies the functional response class within which topographies vary. The same child asking to play the video could be said to have emitted topographical variability, exhibited variant topographies, emitted topographically variant responses, or engaged in variant responding. If the same topography is exhibited across instances of a mand, the pattern of responding is invariant, as in “topographically invariant manding,” “topographically invariant responding,” or engaging in “invariant responding.” Invariant manding may be classified as an invariance problem that warrants intervention (Carr & Kologinsky, 1983; Rodriguez & Thompson, 2015). Varying the reinforcers requested across instances of manding—such as asking a spouse for help carrying the groceries from the car into the house, and then asking them to help place groceries into the refrigerator—is a nonexample of within-mand topographical variability, within or across modalities, because the mands are by definition controlled by different reinforcers (i.e., carrying groceries into the house vs. moving grocery items from bags to the refrigerator). This would instead be an example of across-mand variability.

Variant mand topographies may be evoked or emitted. Discriminative stimuli for reinforcement evoke variant mand topographies. Discriminative stimulus control is demonstrated when, relative to a context in which the discriminative stimulus is absent, in the presence of an antecedent stimulus correlated with a schedule of reinforcement selective for variant responding, responses are more likely to be different from prior instances. For example, due to a history of differential reinforcement for varying the form of the mand for cookies given by his grandmother, a child may learn to vary between “Can I have a cookie?” and “May I have a cookie?” in the presence of his grandmother but repeatedly insist “I want a cookie!” in the presence of his grandfather. Brodhead et al. (2016) provided an example of discriminated mand variability reinforced by lag schedules (also see Silbaugh et al., 2018).

Topography-based within-mand variability may or may not result in a permanent product. For example, varying spoken words to produce access to reinforcement does not leave a permanent product unless the verbal auditory stimulus is recorded by technology. Written or typed mands produce permanent products (i.e., a written word or digitally displayed word, respectively). Similarly, some types of topography-based mand variability that produce products are extremely rare, such as writing requests in the sand (e.g., “Help!” while stranded on an island), but nevertheless may occur. Topography-based variability may occur within or across vocal and nonvocal topographical modalities.

Across Vocal Topographies

A speaker may vary mand topographies within a vocal topographical modality but across topographies, such as a student vocalizing “teacher,” “hey,” “excuse me,” or “call on me” when attention is withheld by a teacher (see Fig. 2). Mands composed of multiple response topographies are functional response classes that may in some cases consist of a response class hierarchy (Baer, 1982; Silbaugh et al., 2018).

For example, Silbaugh et al. (2018) evaluated the effects of a Lag 1 schedule of positive reinforcement on within-mand vocal topographical variability in two children with ASD. First, the researchers conducted a mand topography invariance assessment for each participant to identify two existing repetitive mands and to select two new vocal mand topographies to target for incorporation into those mands as alternative topographies with lag schedules during the treatment evaluation. Sessions began after a brief period of access to the reinforcer and were 5 min in duration. Jack’s reinforcers were cupcake sprinkles and brief access to a tabletop DVD video (i.e., movie). Only one reinforcer (i.e., either cupcake sprinkles or DVD) was available each session. The invariant topography for cupcake sprinkles was “sprinkles,” and the invariant topography for DVD access was “movie.” Alternative topographies were “candy” and “share” for sprinkles and “watch” and “play” for DVD access. Each trial began when the experimenter terminated access to the reinforcer (i.e., EO). During Lag 0 (i.e., baseline), the experimenter reinforced every instance of independent vocal manding regardless of variance. During the Lag 1 plus progressive time-delay condition (i.e., the delay to a prompt systematically increased by 2 s based on predetermined criteria), if a vocal response topography differed from the previous vocal response topography before the end of the time delay, the experimenter reinforced the response. If a variant response did not occur, the experimenter prompted a variant vocal topography by modeling one of the two target alternative topographies selected prior to the treatment evaluation, and reinforced the prompted variant response. The results for Jack (and participant two) displayed in equal-interval line graphs showed that the Lag 1 plus progressive time-delay condition increased variability in vocal topographical mand variability in both mands (i.e., for Jack, the mand for cupcake sprinkles and the mand for DVD access) and decreased invariant manding.

Across Nonvocal Topographies

A speaker may vary mand topographies within a nonvocal topographical modality (e.g., sign), but across topographies, such as a student signing “later,” “break please,” or “not now” when presented with a demand such as a chore or academic task (see Fig. 2). Some variations in this dimension may result in permanent products, such as if a speaker emitted those same mand topographies in writing.

Silbaugh and Falcomata (2019) replicated the lag schedule plus progressive time-delay procedures Silbaugh et al. (2018) used to reinforce mand variability, but targeted sign mand variability and the acquisition of a mand response class hierarchy. The participant was a largely nonvocal boy with ASD. Before the treatment evaluation, researchers used a semistructured play session to identify toy or activity reinforcers and assess the participant’s responsiveness to sign mand training. The training demonstrated the participant could rapidly acquire an arbitrary sign mand topography, suggesting he might subsequently be responsive to treatment. The experimenter selected three novel sign mand topographies for producing access to Play-Doh as the target sign mand topographies for the treatment evaluation. All sessions were 5 min in duration. During the Lag 0 (i.e., baseline) condition, the experimenter delivered 20 s of Play-Doh access and descriptive praise contingent on independent instances of manding with the sign “want.” During the Lag 1 plus progressive time-delay condition, the experimenter delivered 20 s of Play-Doh access and descriptive praise contingent on prompted and independent variant sign mand topographies (constrained to only those target mand topographies selected before the treatment evaluation). The results displayed in equal-interval line graphs showed that the Lag 1 plus progressive time-delay condition increased variability in sign manding but did not decrease invariant sign manding. Subsequent analyses, similar to the prior study, suggested that the treatment established a sign mand response class hierarchy and altered the relative response strength of members of the response class across sessions.

Combination of Across Topographies and Across Topographical Modalities

Alternatively, a speaker may vary mand topographies across topographical modalities while requesting a glass of water by vocalizing the word, signing (nonvocal), or writing (nonvocal) the word (Fig. 3). Some variations along this dimension may result in permanent products, such as printed words. To the best of my knowledge, no studies have measured or arranged a contingency selective for this mand variability dimension.

Fig. 3.

Variability across topographical modalities (i.e., vocal × gestural). Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variation in response topographies. Diagonal solid lines represent variation across modality and topography. EO = establishing operation; MT = topographical modality; R = response topography; S = reinforcer

Selection-Based Within-Mand Variability

A contingency diagram of selection-based mand variability is displayed in Fig. 4. Variant responding consists of the selection of different selection-based modalities, across instances of the mand. For example, to request a break from academic work, a child may press a microswitch, exchange a picture card, tap an icon on a tablet, or point to a break card. Note also that small topographical variations may accompany variation across the stimuli selected (e.g., point, touch, or pick up, reach, and release) but that reinforcement is specifically dependent on the stimuli selected. Selection-based within-mand variability may or may not result in a permanent product. For example, mand variations that comprise the pictures or printed word icons arranged on an “I want” strip using the Picture Exchange Communication System produce permanent products. However, mand variations that comprise pressing a microswitch with a prerecorded message saying “toys please” do not produce a permanent product.

In the context of FCT to treat challenging behavior, Adami et al. (2017) evaluated the effects of a lag schedule of reinforcement on mand variability and challenging behavior in two males with ASD. This study is important because it was the first to show that FCT could reduce challenging behavior to clinically significant levels while reinforcing within-mand selection-based mand variability. The treatment evaluation was preceded by functional analyses and mand modality assessments to identify the function of the participants’ challenging behavior and assess mand proficiency. The mand modalities were nonvocal selection based (i.e., iPad activation, card exchange, microswitch) and topography based (i.e., vocal). During baseline, no modalities were present, mands were extinguished, and the experimenters reinforced challenging behavior on an FR1 schedule. During the FCT/Lag 0 condition, mand modalities were concurrently available, challenging behavior was extinguished, and the experimenters reinforced manding, regardless of modality, on an FR1 schedule. During the FCT/Lag 1 condition, again mand modalities were concurrently available and challenging behavior was extinguished, but the experimenters reinforced variant manding across the nonvocal selection-based modalities and vocal manding. For both participants, FCT/Lag 1 increased rates of variant manding. Despite the availability of multiple modalities, manding was highly repetitive (i.e., restricted largely to one modality) during Lag 0 conditions, consistent with the notion that some individuals with ASD who receive conventional mand training may trend toward highly repetitive manding when contingencies selective for variability are not arranged. The authors did not assess vocal and nonvocal selection-based mand variability separately, so the effects of the lag schedule on specific dimensions of the participants’ mand variability are unknown.

Similarly, Ferguson et al. (2019) compared the effects of small and large magnitudes (i.e., actual quantities) of edible reinforcement on mand variability in four individuals with ASD. For each nonvocal participant, five modalities were present during sessions. Reinforcement was contingent on variant mands across the nonvocal modalities. The researchers observed relatively more variability during Lag 1 schedule sessions when giving the reinforcer in larger quantities (i.e., four edibles instead of one), suggesting this particular mand variability dimension is sensitive to reinforcer quantity.

Combination of Across Topography-Based and Across Selection-Based Modalities

A contingency diagram of the combination of topographies and stimulus modality mand variability is displayed in Fig. 5. Variant responding consists of varying across topography-based and selection-based modalities across instances of manding. For example, a child with language delays who is taught multiple responses to obtain attention might request attention from an adult by first saying the adult’s name (i.e., topography based), then exchanging a picture card (i.e., selection based) if the listener does not respond. This dimension of mand variability differs from that illustrated in Fig. 3 in that the speaker must alternate between topography- and selection-based modalities (i.e., in Fig. 3, the speaker alternates between vocal and nonvocal topography-based modalities). Variations along this dimension of mand variability may produce permanent products, such as picture cards arranged on an “I want” strip or words or pictures displayed on a tablet or similar augmentative alternative communication device. Studies are needed to examine the effects of contingencies selective for this mand variability dimension.

Fig. 5.

Contingency diagram of variability across topography-based and selection-based modalities. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variation in responding. Diagonal solid lines represent variation across modality and topography. EO = establishing operation; M = selection-based modality; MT = topographical modality (i.e., vocal or nonvocal); R = response topography; S = reinforcer

Across Stimuli Within a Selection-Based Modality

A contingency diagram of mand variability across stimuli within a selection-based modality is displayed in Fig. 6. Variant responding consists of varying selections across stimuli embedded in a given nonvocal modality across instances of manding, and may or may not include topographical variations. For an example of this dimension without topographical variations, in a communication application on an electronic tablet, a nonvocal individual uses their index finger to tap icons corresponding to “Want to play,” then again with their index finger taps the icons corresponding to “Can we play now?” This type of variability most closely resembles the kind of sequence variability most commonly studied in basic research on the reinforcement of variability (e.g., Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020). Some variations along this dimension may produce permanent products, such as pictures or words displayed on a tablet-based communication application. To the best of my knowledge, no studies have measured or arranged contingencies specifically for this mand variability dimension. Future research could draw knowledge from the basic literature and examine how reinforcing this dimension of mand variability may promote the expansion of one’s verbal repertoire (i.e., use of more icons, longer sequences, etc.).

Fig. 6.

Contingency diagram of across-stimuli variability within a selection-based mand modality. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variability in discriminative stimuli selected. SD = discriminative stimulus; EO = establishing operation; M = selection-based modality; R = response; S = reinforcer

Combination of Across Topographies and Across Stimuli Within a Selection-Based Modality

A contingency diagram of the mand variability across topography and across stimuli is displayed in Fig. 7. Variant responding consists of varying across topographies and stimuli embedded in a given selection-based modality across instances of manding. For example, in a communication application on an electronic tablet, a nonvocal individual uses their thumb to tap icons corresponding to “Want to play,” then with their index finger taps the icons corresponding to “Can we play now?” Variations along this dimension of mand variability may produce permanent products, such as changes in the pictures or text displayed on a tablet-based communication application. It does not appear that any studies that have measured or arranged a contingency selective for this mand variability dimension.

Fig. 7.

Contingency diagram of variability across nonvocal topographies and variability across stimuli within a selection-based modality. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variability in discriminative stimuli selected (left) or response topography variability (right). Diagonal solid lines represent variability across nonvocal topographies and discriminative stimuli. SD = within-modality discriminative stimulus; EO = establishing operation; MT = topographical modality; R = response topography; S = reinforcer.

Variability Across Nonvocal Topographies and Selection-Based Modalities

A contingency diagram of variant manding across nonvocal topographies and across selection-based modalities is displayed in Fig. 8. Variant responding consists of varying across topographies and across selection-based mand modalities—for example, using the index finger to tap an icon in a communication application on an electronic tablet, then grasping and exchanging a written text card. The second response is variant because it differs in topography and the selection-based modality. If a speaker grasped a written text card and exchanged it on one trial, then touched the written text card with their index finger on the next trial, the second trial response would be invariant because although the topography varied, the selection-based modality was the same. Variations along this dimension of mand variability may produce permanent products, such as changes in the placement of pictures or written text cards, or text displayed on a tablet-based communication application. To the best of my knowledge, no studies have measured or arranged a contingency selective for this mand variability dimension.

Fig. 8.

Contingency diagram of variability across nonvocal topographies and variability across selection-based modalities. Note. Solid horizontal lines represent controlling relations between responses and stimuli. Broken vertical lines represent variation in selection-based modalities (left) and variation in nonvocal topography-based responding (right). Diagonal solid lines represent variation across nonvocal topographies and selection-based modalities. SD = within-modality discriminative stimulus; EO = establishing operation; M = selection-based modality; MT = topographical modality; R = response topography; S = reinforcer

Discussion

This article examined the concept of mand variability and its reinforcement. The proposed eight mand variability dimensions are the products of my conceptual analysis and may be considered an attempt to extend Skinner’s conceptualization of the mand by focusing on how manding can vary. Researchers interested in applying the new proposed mand variability dimensions in future experimental analyses of mand variability can refer to Table 2 for a hypothetical set of operational definitions and examples corresponding to each mand variability dimension. Figures 1–8 may assist researchers and practitioners in discriminating between the proposed mand variability dimensions and facilitate teaching these concepts to students. Together, the mand variability dimensions, accompanying figures, and operational definitions developed in the current article comprise a framework. In theory, this framework could be applied in future research to experimentally evaluate the effects of environmental manipulations on specific mand variability dimensions, and study the adaptive quality (i.e., extent to which it increases contact with reinforcement, minimizes contact with aversive stimuli, or both) and social validity of the changes in mand variability. Ultimately, the current conceptual analysis of mand variability dimensions may advance the analysis of verbal behavior by enabling a more precise empirical characterization of the variables that control manding.

Table 2.

Some hypothetical dependent variables in the experimental analysis of mand variability

| Dependent variable | Operational definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Overall manding | The combination of independent variant and independent invariant manding. | See Adami et al. (2017; i.e., “total mands”). |

| Invariant manding | A response that is the same as the previous response in terms of topography, the stimulus selected, the modality selected, or a combination of these based on the experimental arrangement. | See Silbaugh et al. (2018; i.e., “independent invariant manding”). |

| Topographically variant vocal manding | A vocal mand topography that differs from the last vocal mand topography. A vocal mand topography is different if one or more words differ from the last vocal mand topography and begin following a 1-s or longer pause in vocalizations. | Saying “Apple please,” then 1 s later saying “Can I have a slice?” (see Fig. 2). |

| Topographically variant nonvocal manding | A nonvocal mand topography that differs from the last nonvocal mand topography, following a 1-s or longer pause in nonvocal manding. | Sign manding “I want apple,” then sign manding “Apple slice please” after no less than a 1-s pause (see Fig. 2). |

| Variant manding across topographical modalities | A mand topography that differs in modality (e.g., sign or vocal) from the last mand topography, following a 1-s or longer pause in manding, even if two modalities co-occurred. | If a speaker gestures to apple slices, then asks “Can I have one?” the second response is variant because the participant switched topographical modalities. Similarly, if a participant gestures to apple slices, then simultaneously gestures and says “Apple please,” the second response consists of a combination of vocal and nonvocal modalities and therefore differs from the prior response, which occurred in only one topographical modality (see Fig. 3). |

| Variant manding across nonvocal selection-based modalities | A mand modality selection that differs from the last mand modality selection, after no less than a 1-s pause, regardless of the topography (e.g., touching, picking up) of the selection. | Selecting a picture card that says “Apple please,” then pressing a microswitch that plays a prerecorded message “Apple please.” Or pressing a red microswitch, then tapping an icon on a tablet application (see Fig. 4). |

| Variant manding across topographical modalities and selection-based modalities | An instance of manding that differs in the overarching category of modality (i.e., topography based or selection based) from the last instance of manding, following a 1-s or longer pause in manding. | Saying “apple,” then pressing a microswitch that says “apple.” Or tapping an icon on a tablet application that says “apple,” then signing “apple” (see Fig. 5). |

| Variant nonvocal manding across stimuli within a selection-based modality | An instance of selection-based manding that differs in the stimuli selected within a given modality (e.g., tablet application displaying multiple icons) from the last instance of manding, regardless of topography, following a 1-s or longer pause in manding. | If a participant taps the “please” icon to mand for an apple, then taps a series of icons to form the sentence “I want apple,” the second response is variant because different stimuli within the tablet application were selected. However, if the participant taps the “please” icon once, then taps the “please” icon again, the second response is invariant (see Fig. 6). |

| Variant manding across nonvocal topographies and across stimuli within a selection-based modality | An instance of nonvocal manding that differs in the stimuli selected within a given modality (e.g., tablet application displaying multiple icons) from the last instance of manding, and differs in topography, following a 1-s or longer pause in manding. | For example, if a participant taps the “please” icon with their index finger, then taps a series of icons to form the sentence “I want apple” with their thumb, the latter is variant because different stimuli within the tablet application were selected by a different topography. However, if the participant taps the “please” icon with their elbow once, then taps the “please” icon with their elbow again, the latter response is invariant because the response did not differ in terms of both modality and topography. Similarly, if the participant taps the “please” icon with their elbow, then taps the “apple” icon with their elbow, the second response is still invariant because the topography did not vary (see Fig. 7). |

| Variant manding across nonvocal topographies and across selection-based modalities | An instance of manding that differs in nonvocal topography and selection-based modality from the last instance of manding, following a 1-s or longer pause in manding. | If a participant selects a picture card by pointing to it, then presses a microswitch with their hand, the second response is variant because it differed both in terms of the nonvocal topography and the selection-based modality. However, if the participant taps an icon on the tablet with their pointer finger, then taps the picture card with their pointer finger, the second response is invariant because although the selected modality varied, the topography did not vary (see Fig. 8). |

Another implication of the current conceptual analysis of mand variability is that by more precisely defining, assessing, and reinforcing select dimensions of mand variability, practitioners may more effectively predict and control mand variability when it is helpful to do so in education, clinical service, or other socially important contexts. For example, some individuals with manding deficits or delays could be more responsive to mand training following mand variability training targeting specific dimensions. When individuals with ASD are underresponsive to mand training, assessments may be used to develop mand variability deficit profiles prescriptive for mand variability training that enable a more individualized mand training approach. Preliminary findings from Silbaugh and Falcomata (2019) suggested mand variability training at the early onset of mand training may be used to teach multiple topographies within a single mand response class more quickly than conventional methods. The extent to which reinforcing mand variability may result in socially meaningful outcomes for individuals with ASD is not readily apparent for some of the dimensions. For example, it is not clear why we would expect differentially reinforcing “variant manding across nonvocal topographies and across selection-based modalities,” such as tapping the “want” icon with an index finger and subsequently tapping it with a thumb, to produce socially meaningful outcomes. Nevertheless, future research could address this and similar questions. For example, future research could evaluate the extent to which the effects of differential reinforcement of one or more specific mand variability dimensions may generalize in beneficial ways to nontargeted mand variability dimensions or perhaps variability in other verbal operants.

The current conceptual analysis may have important implications for research on variables that mitigate resurgence during challenges to treatment following FCT. Resurgence “refers to a procedure, outcome, and process by which previously suppressed responding recurs following discontinuation of reinforcement of an alternative response” (St. Peter, 2015, p. 253). In a three-phase resurgence paradigm, during Phase 1, target responding (i.e., challenging behavior) is reinforced. During Phase 2, target responding is extinguished, whereas alternative responding (i.e., manding) is reinforced. During Phase 3, all responding is placed on extinction, and the recurrence of challenging behavior above Phase 2 levels is called resurgence (St. Peter, 2015). Some researchers have suggested that differentially reinforcing multiple alternative responses during Phase 2 could mitigate the resurgence of challenging behavior by promoting the persistence of manding that competes with challenging behavior (e.g., Falcomata & Wacker, 2012). Two general approaches to reinforcing multiple alternative responses during FCT (i.e., equivalent to Phase 2 of a three-phase resurgence model) have emerged: serial differential reinforcement of multiple functional communication responses (e.g., Lambert et al., 2015) and differential reinforcement of mand variability with lag schedules (e.g., Falcomata et al., 2018). By identifying multiple dimensions of mand variability, the current conceptual analysis might prompt researchers to pose different questions about the effects of Phase 2 reinforced mand variability on resurgence or other recurrence phenomena by examining a wider range of mand variability contingencies. For example, because multiple schedules embedded in FCT can affect rates of resurgence of challenging behavior during an extinction challenge (e.g., Fisher et al., 2019), the current conceptual analysis raises new questions such as whether the effects of lag reinforcement of mand variability within or across selection-based mand modalities (which require conditional discriminations) on resurgence might differ from the effects of lag reinforcement of mand variability within or across topographical mand modalities that do not involve conditional discriminations.

By comparing responsiveness to mand variability between typically language individuals and individuals with ASD, we might find subtypes of manding deficiencies characterized by deficits in or more specific mand variability dimensions. Additionally, future research could examine whether targeting one or more specific mand variability dimensions may be more effective at increasing vocal mand variability for some individuals with manding deficiencies. The idea that reinforcing mand variability, even when vocal manding is not required, may increase vocal manding is supported by the observation noted earlier in Falcomata et al. (2018) that vocal manding increased in a relatively nonvocal boy with ASD during FCT coinciding with extended contact with escalating lag schedule values.

As has been discussed in prior lag schedule research (Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020), more research is needed to assess the social validity of interventions that reinforce operant variability, and such is the case for mand variability as well. Future research could evaluate whether changes in specific targeted dimensions of mand variability correlate with stakeholders’ perceptions of social validity (Wolf, 1978) or intervention recipients’ choice of treatment (Hanley, 2010). Everything we know about mand variability and its reinforcement comes from studies with individuals with language delays or deficits. Thus, studies of reinforced mand variability in individuals with typical language are essential for advancing our knowledge in this area.

One limitation of the current study is that I did not consider temporal dimensions of mand variability, although that too could be further examined. Conceptual analyses of variability in other verbal operants are also needed. Most of the studies selected to illustrate each dimension of mand variability were identified in a previously published systematic synthesis of lag schedule research in humans (Silbaugh, Murray, et al., 2020). However, some studies were not (e.g., Carr & Kologinsky, 1983). Therefore, to the extent that the current study is conceptualized as a narrative review, the subjectivity with which those studies were selected (and other studies were not) may be considered a limitation on replicability and generality (King et al., 2020).

Declaration

Conflict of interest

I report no potential conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

This study did not involve human participants or animals. Accordingly, informed consent does not apply to this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adami, S., Falcomata, T. S., Muething, C. S., & Hoffman, K. (2017). An evaluation of lag schedules of reinforcement during functional communication training: Effects on varied mand responding and challenging behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10, 209–213. 10.1007/s40617-017-0179-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Baer, D. M. (1982). The imposition of structure on behavior and the demolition of behavior structures. In H. E. Howe (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press. [PubMed]

- Bernstein, H., & Sturmey, P. (2008). Effects of fixed-ratio schedule values on concurrent mands in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(2), 362–370. 10.1016/j.rasd.2007.09.001

- Bloom SE, Lambert JM. Implications for practice: Resurgence and differential reinforcement of alternative responding. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48:781–784. doi: 10.1002/jaba.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead, M. T., Higbee, T. S., Gerencser, K. R., & Akers, J. S. (2016). The use of a discrimination-training procedure to teach mand variability to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(1), 34–48. 10.1002/jaba.280 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carr, E. G., & Kologinsky, E. (1983). Acquisition of sign language by autistic children: II. Spontaneity and generalization effects. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16(3), 297–314. 10.1901/jaba.1983.16-297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Falcomata, T. S., & Wacker, D. P. (2012). On the use of strategies for programming generalization during functional communication training: A review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25(1), 5–15. 10.1007/s10882-012-9311-3

- Falcomata, T. S., Muething, C. S., Silbaugh, B. C., Adami, S., Hoffman, K., Shpall, C., & Ringdahl, J. E. (2018). Lag schedules and functional communication training: Persistence of mands and relapse of problem behavior. Behavior Modification, 42(3), 314–334. 10.1177/0145445517741475 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, R. H., Falcomata, T. S., Ramirez-Cristoforo, A., & Landono, F. V. (2019). An evaluation of the effect of varying magnitudes of reinforcement on variable responding exhibited by individuals with autism. Behavior Modification, 43(6), 774–789. 10.1177/0145445519855615 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fisher, W. W., Fuhrman, A. M., Greer, B. D., Mitteer, D. R., & Piazza, C. C. (2019). Mitigating resurgence of challenging behavior using the discriminative stimuli of a multiple schedule. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113(1), 263–277. 10.1002/jeab.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer, R. D. (2008). The ontogenetic selection of verbal capabilities: Contributions of Skinner’s verbal behavior theory to a more comprehensive understanding of language. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Theory, 8(3), 363–386 https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen8/num3/

- Hanley GP. Toward effective and preferred programming: A case for the objective measurement of social validity with recipients of behavior-change programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03391754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, S. A., Kostewizc, D., Enders, O., Burch, T., Chitiyo, A., Taylor, J., DeMaria, S., & Reid, M. (2020). Search and selection procedures of literature reviews in behavior analysis. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 43, 725-760. 10.1007/s40614-020-00265-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lambert JM, Bloom SE, Samaha AL, Dayton E. Serial functional communication training: Extending serial DRA to mands and problem behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2015;32(4):311–325. doi: 10.1002/bin.1493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, McComas JJ, Jawor J. The effects of differential and lag reinforcement schedules on varied verbal responding by individuals with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(4):391–402. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Establishing operations and the mand. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1988;6:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03392824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael, J. (2004). Concepts & principles of behavior analysis. Association for Behavior Analysis International.

- Miguel CF. Jack Michael’s motivation. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2013;29:3–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03393119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S, Neuringer A. Variability is an operant. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1985;11(3):429–452. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.11.3.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DC. Is variability an operant? Introductory remarks. The Behavior Analyst. 2012;35(2):209–211. doi: 10.1007/bf03392279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter B, Brown DL. A review of studies examining the nature of selection-based and topography-based verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1997;14:85–104. doi: 10.1007/BF03392917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley KC, Battaglia AA, Dadakhodjaeva K, Ford WB, Robbins K. Increasing behavioral variability and social skill accuracy in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2018;27:395–418. doi: 10.1007/s10864-018-9294-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radley KC, Dart EH, Helbig KA, Schrieber SR. An additive analysis of lag schedules of reinforcement and rules on novel responses of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2020;32:395–408. doi: 10.1007/s10882-018-9606-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radley KC, Dart EH, Moore JW, Lum JDK, Pasqua J. Enhancing appropriate and variable responding in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2017;20:538–548. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2017.1323973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez NM, Thompson RH. Behavioral variability and autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(1):1–21. doi: 10.1002/jaba.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman, M. (1960). Tactics of scientific research. Basic Books.

- Silbaugh BC, Falcomata TS. Effects of a lag schedule with progressive time delay on sign mand variability in a boy with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00273-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbaugh BC, Falcomata TS, Ferguson RH. Effects of a lag schedule of reinforcement with progressive time delay on topographical mand variability in children with autism. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2018;21:166–177. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2017.1369190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbaugh, B. C., Murray, C., Kelly, M. P., & Healy, O. (2020). A systematic synthesis of lag schedule research in individuals with autism and other populations. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8, 92-107. 10.1007/s40489-020-00202-1

- Silbaugh, B. C., Swinnea, S., & Falcomata, T. S. (2020). Replication and extension of the effects of lag schedules on mand variability and challenging behavior during functional communication training. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 36, 49-73. 10.1007/s40616-020-00126-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Silbaugh BC, Wingate HV, Falcomata TS. Effects of lag schedules and response blocking on variant food consumption by a girl with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2016;32(1):21–34. doi: 10.1002/bin.1453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner BF. Selection by consequences. Science. 1981;213(4507):501–504. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0002673X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter CC. Six reasons why applied behavior analysts should know about resurgence. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2015;41(2):252–268. doi: 10.5514/rmac.v41.i2.63775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, M. L., & Partington, J. W. (1998). Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. AVB Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wolf MM. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11(2):203–214. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K, Pound S, McCammon MN, Chezan LC, Drasgow E. A systematic review of interventions to promote varied social-communication behavior in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification. 2019;43(6):790–818. doi: 10.1177/0145445519859803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K, Slocum TA, Kunnavatana S. Promoting behavioral variability in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A literature review. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2014;29(3):180–190. doi: 10.1177/1088357614525661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]