Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a stress-related plant hormone, which is reported to confer drought tolerance. A key enzyme in ABA biosynthesis is 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase. In this study, changes in morphological, physiological response, HbNCED3, and ABA accumulation of RRIM 623 and PB 5/51 rubber clones were observed at different time points of water deficit conditions (0, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days of withholding water). During water deficit, the relative water content (RWC), photosynthetic rate (Pn), and stomatal conductance (Gs) decreased, whereas the electro leakage (EL) increased. The magnitudes of the changes in these parameters were greater for PB 5/51 than for RRIM 623. Therefore, RRIM 623 was designated as representative of drought-tolerant clone and PB 5/51 as a drought-sensitive clone. The HbNCED3 transcription level of RRIM 623 showed lower expression compared with that of PB 5/51, which corresponded to the accumulation of ABA. RRIM 623 accumulated less ABA than PB 5/51. The ABA in RRIM 623 gradually increased, especially on the 7th day of withholding water, whereas that in PB 5/51 rapidly increased during the early periods of drought conditions. Additionally, the sensitivity of stomatal response to ABA showed that RRIM 623 had a higher sensitivity than PB 5/51. These results demonstrate that the drought-tolerant rubber clone, RRIM 623, was characterized by lower ABA accumulation during drought stress than the drought-sensitive clone, PB 5/51. The drought tolerance mechanism of the RRIM 623 might be associated with stomatal sensitivity to ABA accumulation under drought stress.

Keywords: Hevea brasiliensis, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase3, Abscisic acid, Stomatal sensitivity, Drought stress

Introduction

There are many impacts of global climate change, especially in agriculture. Drought stress is the most crucial abiotic stress affecting plant growth and production (Fahad et al. 2017). Additionally, rubber trees need to be adapted to being planted in new growing areas where water may be less prevalent than in traditional growing areas. Nontraditional growing areas can be found in parts of several countries, such as northeastern India, northern and northeastern Thailand, East Java in Indonesia, Yunnan in China, or Mato Grosso in Brazil (Sanier et al. 2013). One alternative solution to drought stress is through the use of a drought-tolerant rubber clone.

Understanding Hevea brasiliensis drought response mechanisms is important for breeding drought-tolerant rubber clones. Several studies have been conducted on water stress in rubber trees. Many studies have been undertaken to select drought-tolerant rubber clones, such as drought-tolerant rubber rootstock (Ahamad 1999) and rubber leaves with a higher amount of epicuticular wax (Rao et al. 1988). Transcription levels of drought-responsive transcription factors have been quantified such as WRKY transcription factor (WRKY) and CRT/DRE binding factor (CRT/DRE bf) (Sathik et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2012, 2011). Moreover, functional genes related to drought-tolerant mechanisms have been studied in H. brasiliensis. HbCuZnSOD superoxide dismutase over-expression in the PB260 was found to enhance drought tolerance (Leclercq et al. 2012). Additionally, the expression of energy biosynthesis (HbCOA, HbATP, HbRbsS, and HbACAT) and ROS detoxifying systems (HbAPX, HbCAT, HbCuZnSOD, and HbMnSOD) related genes is meaningfully upregulated by drought stress in the GT 1 clone (Wang 2014).

As multiple strategies are adopted by plants during drought stress, stomatal closure is the first reaction in most plants to drought conditions. It is widely accepted that stomatal closure is induced by endogenous abscisic acid (ABA), which is swiftly produced during drought stress. ABA concentrations increase under drought pressure because of the induction of ABA biosynthesis genes (Iuchi et al. 2001). The rate-limiting enzyme in ABA biosynthesis is the catalytic breakdown of 9-cis-neoxanthin or 9-cis-violaxanthin by a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), which generates C15 intermediate xanthoxin, which is converted by a two-step reaction to ABA (Nambara and Marion-Poll 2005). Therefore, much attention has been focused on NCED gene expression. Drought stress conditions have been shown to induce NCED expression in maize (Tan et al. 1997), bean (Qin and Zeevaart 1999), tomato (Burbidge et al. 1999), Arabidopsis (Iuchi et al. 2001), avocado (Chernys and Zeevaart 2000), and cowpea (Iuchi et al. 2000). However, the functions of the NCED3 gene, ABA accumulation, and stomatal sensitivity to ABA in drought tolerance mechanisms have not been studied in Hevea. To our knowledge, this is the first study on HbNCED3 gene expression to gain novel insights into the role of this gene in response to water stress conditions. Moreover, the reaction of two rubber clones to drought stress was compared through the investigation of the physiological parameters, ABA accumulation, and their stomatal sensitivity to ABA.

Materials and methods

Plant material and drought treatment

Six rubber clones were evaluated for drought-tolerant levels in the preliminary study. Based on the morpho-physiological responses, RRIM 623 was the most tolerant of drought, whereas PB 5/51 was among the clones adversely affected by water stress. Therefore, these two rubber clones were selected for further investigation. Two rubber clones comprising PB 5/51 and RRIM 623 seedlings were grown in plastic pots with latosolic red soil in a greenhouse at Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla Province, Thailand. The temperature and humidity were approximately 37 °C and 85%, respectively. Six-month-old seedlings were subjected to drought stress by withholding water, and then leaves in the mature stage were collected at various time points (after 0, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days of withholding water) for relative water content (RWC) and electro leakage (EL) measurements. Additionally, the collected leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at − 80 °C until ABA analysis and RNA extraction. Twenty seedlings for each clone were used to calculate the survival rate after 9 days withholding water and re-watering for 2 weeks.

RWC

The leaf samples were weighed (FW) and then soaked in distilled water for 4 h, blotted dry before the turgid weight measurement (TW). The leaves were kept at 70 °C for 48 h, and the dry weights (DW) were recorded. The RWC was calculated based on the following formula:

Electrolyte leakage

Leaf samples of approximately 0.3 g were washed with deionized water and incubated in deionized water for 2 h at 25 °C. The initial conductivity of the solution (L1) was measured by a conductivity meter. Subsequently, samples were autoclaved at 100 °C for 30 min, and after cooling down, the final conductivity (L2) was measured. EL was calculated by the following formula:

Measurement of physiological parameters

The photosynthesis rate (Pn) and stomatal conductance (Gs) were measured at 0, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days of withholding water, using an LCi Portable Photosynthesis System (ADC BioScientific Ltd., United Kingdom). The measurement of Pn and Gs was recorded between 09:00 and 12:00 am. All measurements were determined on the first pair of fully expanded leaves with three replications.

Measurement of endogenous ABA content

For the determination of ABA content, leaf samples were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Endogenous ABA content was measured using the method described by Kim et al. (2012) with a slight modification. The leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted overnight in an ABA extraction buffer (methanol, containing 100 mg butylated hydroxyl toluene and 0.5 g citric acid monohydrate) with constant shaking at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was passed through a Sep Pak C18-cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The supernatant was evaporated using a speed vac until approximately 50 μL of liquid remained. The sample was resuspended in TBS buffer (50 mM Tris, 1 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl, at pH 7.8). The ABA concentration was quantified with a Phytodetek ABA enzyme immunoassay test kit (Agdia Inc., Elkhart, IN, USA).

Stomatal ABA sensitivity

Stomatal measurements were conducted using the protocol described by Liu et al (2016) with intact leaves from two rubber clones. The samples were soaked in the stomatal opening buffer (10 mM MES, pH 6.2, and 10 mM KCl, 7.5 mM iminodiacetic acid) for 2 h in the presence of light. Subsequently, the samples were incubated in stomatal opening buffer supplemented with 0, 10, 20, 50, or 100 µmol L−1 ABA for 30 min. Additionally, a time course of 20 µmol L−1 ABA-induced stomatal closing was observed. For stomata aperture measurement, each replicate is the average aperture of 30 randomly selected stomata under each treatment. The stomata aperture was determined using a microscope equipped with a digital camera (BX61, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated using a modified CTAB method as previously described by Prabpree et al. (2018). Subsequently, the sample was precipitated overnight with 8 M LiCl at 4 °C. The RNA pellets were dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water (Applichem, Germany). The quality and quantity of extracted RNA were assessed using a BioDrop DUO spectrophotometer. RQ1 RNase-free DNase was used to treat RNA samples to eliminate genomic DNA (Promega, USA). The first strand cDNA was amplified using Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using three biological replicates and three technical replicates. NCED3 primers were designed based on the GenBank nucleotide database (accession number MW847706. The gene-specific primers HbNCED3-F: GAGCAAACCCGCTTCACGAG and HbNECD3-R: GAAGCGGCAAGCGTAACTCAC were used to analyze NCED3 transcription levels. rRNA primers (18S) (F: AAGCCTACGCTCTGGATACATT and R: CCCGACTGTCCCTGTTAATC) were used to normalize the reactions (Sangsil et al. 2016). The amplicon sizes were 110 bp for HbNCED3 and 100 bp for 18 s rRNA. All reactions were performed according to the instructions provided for the ABI Prism 7000 system with Fast Start and Universal SYBR Green Master Mix. The transcription levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method (Pfaffl 2001). Ct values from 18S rRNA were used to normalize Ct data obtained from HbNECD3.

Statistical analysis

The experiment had a completely randomized design with three biological replications. All data were subjected to statistical analysis of variance, and the means were compared using Tukey’s test (R Statistical Software v.3.5.1) at a 0.05 probability level.

Results

Morphological and physiological responses during drought conditions

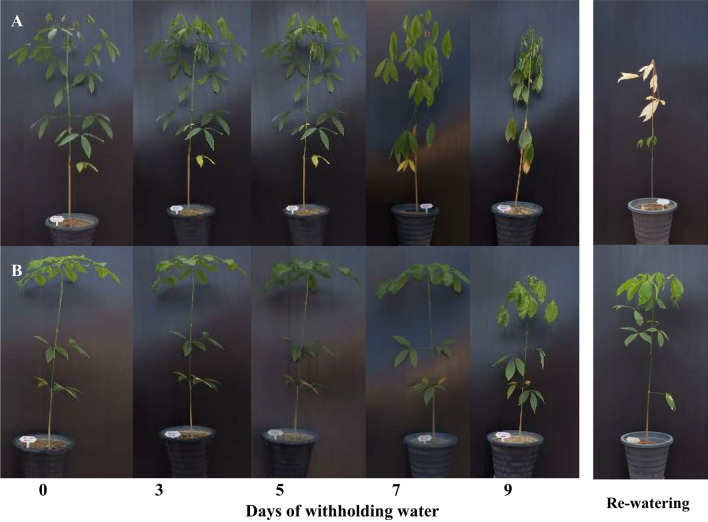

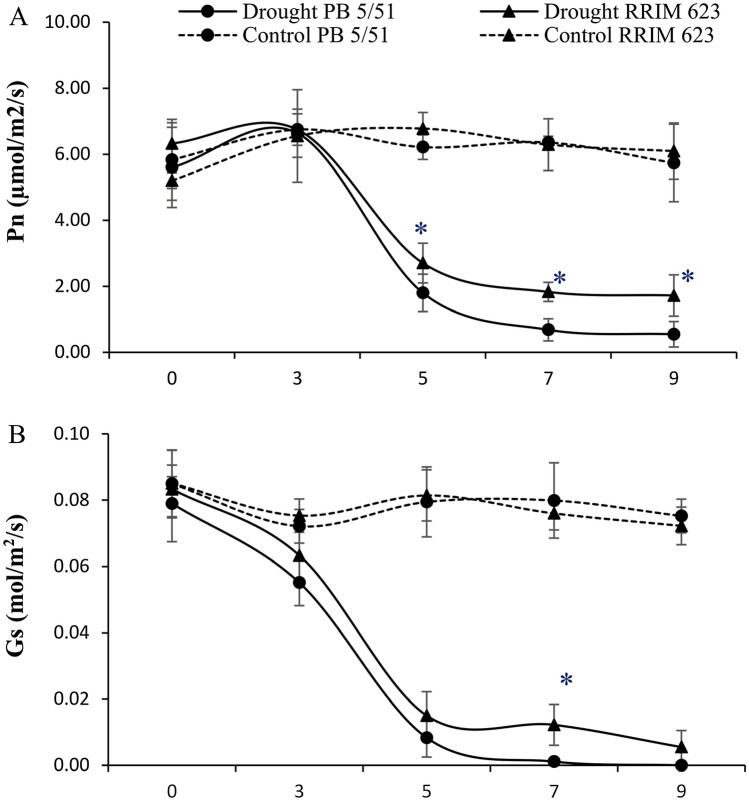

The rubber clones started to show yellowing of some older leaves, and their young leaves displayed wilting symptoms but remained green. After withholding water for 7 days, the leaves of the RRIM 623 plants displayed no wilting symptoms, whereas those of PB 5/51 showed wilting signs (Fig. 1). After 9 days of water retention, the upper leaves of RRIM 623 started to show wilting symptoms, whereas those of PB 5/51 showed severe wilting symptoms. The RWC declined during the progressive drought in all leaves of rubber clones. However, the decline was more pronounced for PB 5/51 than for RRIM 623 (Table 1). Additionally, the EL of leaf increased in drought stress in both rubber clones (Table 1). PB 5/51 had significantly higher EL than RRIM 623. When the plants were re-watered for 2 weeks after drought treatment, only 55% of the PB 5/51 plants could recover, whereas all RRIM 623 plants were revived. By the end of drought treatment, almost all leaves of the PB 5/51 plants were desiccated and brown, whereas some of the leaves of RRIM 623 plants remained turgid and green. Moreover, RRIM 623 exhibited a higher photosynthetic rate (Pn) and stomatal conductance (Gs) than did PB 5/51 during drought treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Morphological changes in two rubber clones comprising PB 5/51(A) and RRIM 623 (B) Pictures of the plant were taken at 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 days of withholding water and then re-watering for 2 weeks

Table 1.

Leaf relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage (EL) measured for two rubber clones at 0, 3, 5, 7, 9 days after water withholding

| Physiological parameters | Days after water withholding (days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| RWC (%) | |||||

| PB 5/51 | 89.77 ± 2.25a | 84.56 ± 2.22 a | 78.98 ± 4.17 a | 63.15 ± 2.04 b | 23.98 ± 3.46b |

| RRIM 623 | 86.25 ± 1.85 a | 85.26 ± 4.99 a | 85.08 ± 4.45 a | 84.19 ± 3.21 a | 76.70 ± 4.83a |

| EL (%) | |||||

| PB 5/51 | 6.39 ± 0.39 a | 12.20 ± 0.41 a | 11.04 ± 0.63 a | 17.33 ± 2.62 a | 33.09 ± 6.18 b |

| RRIM 623 | 6.04 ± 0.51 a | 13.69 ± 1.71 a | 11.19 ± 1.10 a | 12.22 ± 1.09 a | 12.39 ± 0.53 a |

Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE)

Different letter indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) according to the Tukey’s test

Fig. 2.

Changes in photosynthetic rate (Pn, A) and stomatal conductance (Gs, B) of PB 5/51 and RRIM 623 rubber clones under drought stress conditions. Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE). * indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

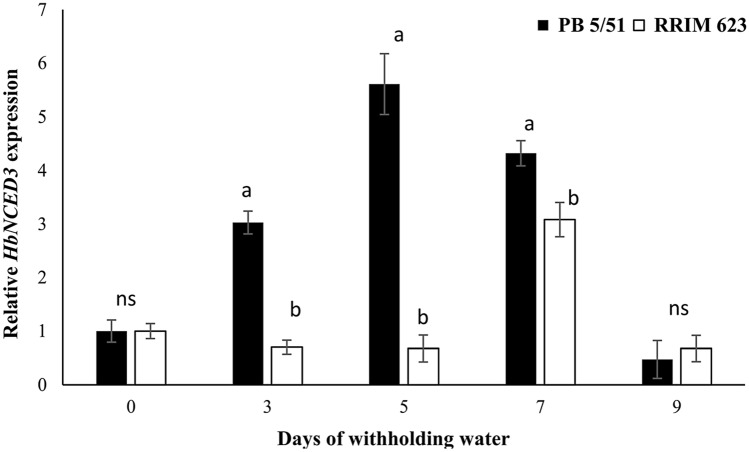

Expression levels of HbNCED3 during drought stress conditions

In this study, the two rubber clones were used for studying the expression profile of the NCED3 gene at 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 days of retaining water. The 18S gene was used as an internal control for all samples. Differential expression of HbNCED3 was found in both rubber clones studied. The increase in HbNCED3 expression in PB 5/51 during drought was higher than that in RRIM 623, which exhibited stable expression at 0, 3, and 5 days and increased to the highest level after 7 days of withholding water. PB 5/51 showed increased expression of the NCED3 gene after withholding water for 3 days and reached its maximum level after 5 days of withholding water then decreased, especially on the 9th day of water retention as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Expression pattern of HbNCED3 in PB 5/51 and RRIM 623 rubber clones after withholding water for 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 days. Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE). Different letters denote significant differences between two rubber clones within each time point (p < 0.05) according to the Tukey’s test

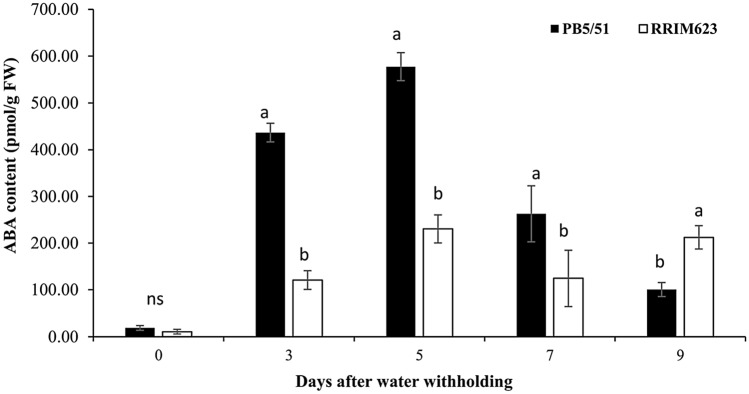

ABA accumulation during drought conditions

Under well-watered conditions, the content of ABA remained at low levels in the leaves of two rubber clones, as shown in Fig. 4. It increased in drought stress, which was associated with increases in the NCED3 expression level for both rubber clones. During drought treatment, RRIM 623 had significantly less ABA accumulation compared with PB 5/51. The leaf ABA content of PB 5/51 increased progressively with drought (Fig. 4). There was a 12.5-fold increase in ABA content in leaves after 3 days of drought and up to a 17.5-fold rise to the highest level on day 5 of retaining water. Alternatively, the leaf ABA content of RRIM 623 remained stable at the early stages of withholding water but gradually increased significantly on the 7th day of water retention.

Fig. 4.

Leaf ABA accumulation of PB 5/51 and RRIM 623 rubber clones after withholding water for 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 days. Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE). Different letters denote significant differences between two rubber clones within each time point (p < 0.05) according to the Tukey’s test

Stomatal sensitivity to ABA

To test whether stomatal movements of rubber clones were related to their sensitivity to ABA, the stomatal closure of intact leaves induced by exogenous ABA at different concentrations was then compared. At 0 µM ABA, the stomatal aperture of RRIM 623 was similar to or slightly smaller than PB 5/51 (Fig. 5A and Table 2). The result showed that the stomata in the leaves of RRIM 623 slightly closed at a concentration of as low as 10 µmol L−1, but it needed more than 20 µmol L−1 exogenous ABA to induce stomatal closure in PB 5/51 leaves. Time course of 20 µmol L−1 ABA-induced stomatal closing showed that PB 5/51 leaves needed more than 20 min to enhance stomatal closure, whereas stomata in the leaves of RRIM 623 start to close in 10 min (Fig. 5B and Table 3). These results suggest that the stomata in RRIM 623 had higher sensitivity to ABA than those in the PB 5/51 clone. This may result in better drought adaptation in RRIM 623 even though ABA accumulation was less than that in PB 5/51 during drought conditions.

Fig. 5.

The effect of ABA concentrations (A) and time-course changes in response to 20 μM ABA (B) on the sensitivity of stomatal aperture in PB5/51 and RRIM 623 rubber clones. Scale bar = 10 μm

Table 2.

Stomatal aperture in detached leaves of two rubber clones at different ABA concentrations

| Clones | ABA concentrations (µM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 100 | |

| PB 5/51 | 1.81 ± 0.07a | 1.69 ± 0.16a | 1.31 ± 0.52a | 1.29 ± 0.41a | 1.21 ± 0.05a |

| RRIM 623 | 1.61 ± 0.05a | 1.35 ± 0.07b | 1.19 ± 0.22b | 1.01 ± 0.08b | 0.89 ± 0.07b |

Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE)

Different letter indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) according to the Tukey’s test

Table 3.

Stomatal aperture in detached leaves of two rubber clones at time-course changes in response to 20 μM ABA

| Clones | Time after ABA treatment (min) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 40 | |

| PB 5/51 | 1.78 ± 0.05a | 1.57 ± 0.12a | 1.34 ± 0.32a | 1.23 ± 0.11a |

| RRIM 623 | 1.75 ± 0.05a | 1.48 ± 0.09a | 1.10 ± 0.26ab | 0.88 ± 0.09b |

Data are presented as the mean of three biological replication (± SE)

Different letter indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) according to the Tukey’s test

Discussion

Physiological drought stress-related traits, RWC, and EL were determined during the drought stress treatment. RWC is one of the most potent parameters representing turgor pressure and is easily measured. Moreover, it may even be more beneficial than total water potential in the case of tissue stress determination. Wang (2014) reported that the RWC in the leaves of GT1 seedlings continuously reduced with the drought stress severity, decreasing by almost 20% at 9 days without water compared with that before withholding water (day 0), which is similar to our result. RWC in PB 5/51 decreased by almost 40% at 9 days without water, whereas RWC in RRIM 623 decreased only by 10% compared with that before withholding water (Table1). Therefore, it is unsurprising that RRIM 623 started to show wilting symptoms 9 days after water withholding. Electrolyte leakage is an inexpensive and nondestructive method that determines the damages of the cell membrane during drought stress (Bajji et al. 2002). EL increased 9 days after retaining water. RRIM 623 exhibited lower EL as compared with the sensitive clones during the drought period. The results supported the fact that a significant indicator of drought-tolerant plants is the maintenance of cell integrity and stability under drought stress (Tint et al. 2011).

ABA is involved in mediated response to drought stress by induced stomatal closure. NCED3 is a critical enzyme involved in ABA hormone biosynthesis, which has been shown to accumulate in cells undergoing drought response. Previous works revealed that roots and leaves of several plant species could be triggered for NCED transcript accumulation during drought stress (Nambara and Marion-Poll 2005). NCED3 gene expression has been investigated in various plants. The expression of AtNCED3 was predominantly induced by drought treatment, unlike the other seven NCED genes from Arabidopsis (Iuchi et al. 2001). Moreover, the expression of AtNCED3 was upregulated significantly, and the production of ABA was increased under drought stress (Seki et al. 2002). JaNCED3 and JaNCED5 were observed to be strongly upregulated in the roots of Jatropha curcas (Zhang et al. 2015). A similar result was observed in Fraxinus velutina, which indicated that FvNCED3 expression increased under drought stress (Li et al. 2019). In Malus prunifolia, MpNCED2 expression was gradually upregulated with time and peaked on day 4 of withholding water to about 40 times greater than that at the beginning, whereas the face of MpNCED1 showed a slightly downregulated transcription level (Xia et al.2014). In this research, we found that drought stress leads to upregulation of the HbNCED3 gene, which agrees with earlier reports. Drought-sensitive clones (PB 5/51) showed a higher transcription level of HbNCED3 gene than drought-tolerant clones (RRIM 623). The HbNCED3 induction rates in leaves correlated with leaf ABA accumulation. Endogenous ABA content dramatically increased in PB 5/51 which showed more rapid upregulation of HbNCED3 than that in RRIM 623. In this regard, our observations are similar to the ones reported in Manihot esculenta (Arango et al. 2010). MeNCED induction was associated with increased ABA levels with an almost collinear trend under drought stress.

Several studies have confirmed that an increase in leaf ABA content is associated with reduced Gs under drought stress (Pirasteh‐Anosheh et al. 2016; Saradadevi et al. 2017; Brunetti et al. 2019). These reports revealed that the hormone ABA has an essential function in drought stress response in Hevea seedlings. The association between drought tolerance and low ABA accumulation has been demonstrated in grass family plants. In orchard grass, drought-susceptible cultivar exhibited higher leaf ABA accumulation compared with a drought-tolerant cultivar (Volaire et al. 1998). Wang and Huang (2003) reported that a Kentucky bluegrass that exhibited lower ABA content had better turf grass performance, RWC, and Pn under drought stress than drought-susceptible cultivars that had higher ABA accumulation. In another study on cowpea, Lei et al. (2016) found that the drought-sensitive variety had higher ABA content than drought-resistant variety. Moreover, Michelle and Huang (2007) suggested that enhanced ABA accumulation in the drought-susceptible cultivar of bentgrass could be associated with lower Gs that leads to earlier declines in Pn compared with drought-tolerant cultivar. In the present study, RRIM 623 maintained significantly higher Pn and Gs at 5 and 7 days of drought treatment compared with PB 5/51 (Fig. 2). The continued carbon assimilation and photosynthesis rate could extend plant survival during drought stress (Michelle and Huang 2007).

In addition to leaf ABA accumulation under drought stress, Saradadevi et al. (2017) suggested that the diversity in ABA accumulation among wheat genotypes (Triticum aestivum L.) might be related to stomatal sensitivity to ABA concentration. Liu et al. (2016) demonstrated that cucumber grafted onto luffa rootstock (Cs/Lc) had an increased sensitivity to ABA, which contributed to its higher tolerance to drought. Our experiments show that the stomata of RRIM 623 had higher sensitivity to ABA than those of the PB 5/51 clone. Therefore, low ABA accumulation observed during drought treatment in RRIM 623 can lead to partial stomatal closure and help sustain photosynthesis. Furthermore, Li et al. (2017) reported that thinner cuticles in KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 (kai2) mutant might be enhanced non-stomatal water loss under drought conditions. Leaf cuticular wax and cuticle thickness appear to protect plants against water loss, such as rubber tree (Rao et al. 1988), Arabidopsis (Aharoni et al. 2004), and wheat (Bi et al.2017). Future studies on the potential role of leaf cuticular wax production will probably be helpful in the understanding of drought stress-tolerant mechanisms in rubber trees.

Conclusion

The transcription level of the HbNCED3 gene involved in ABA biosynthesis is associated with leaf ABA accumulation. Besides ABA biosynthesis, stomatal sensitivity to ABA might play an essential role in rubber drought tolerance since drought-tolerant rubber clones were characterized by lower ABA accumulation during drought stress. Moreover, the stomata of RRIM 623 had higher sensitivity to ABA than those of the PB 5/51 clone. Taken together, the results offer an exciting insight into the ABA regulation of drought-tolerant rubber trees. RRIM 623 could be significantly exploited to use as germplasm in drought-tolerant breeding programs.

Acknowledgements

This research was granted by the Center of Excellence on Agricultural Biotechnology, Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (AG-BIO/MHESI), the Center of Excellence in Agricultural and Natural Resources Biotechnology (CoE-ANRB): phase 3, Faculty of Natural Resources, Prince of Songkla University. This research was also supported by Prince of Songkla University (Grant no. NAT600522S). The authors gratefully acknowledge the Publication Clinic, Research and Development Office, Prince of Songkla University, for technical comments and improving the manuscript.

Author contributions

KN was responsible for design the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. NW performed the experiment, analysis the data and edited the manuscript. CS and OK participated in the experiment. CN supervised the experiment and reviewed the manuscript. TR were responsible for planning and edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahamad B. Effect of rootstock on growth and water use efficiency of Hevea during water stress. J Rubber Res. 1999;2:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A, Dixit S, Jetter R, Thoenes E, van Arkel G, Pereira A. The SHINE clade of AP2 domain transcription factors activates wax biosynthesis, alters cuticle properties, and confers drought tolerance when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango J, Wüst F, Beyer P, Welsch R. Characterization of phytoene synthases from cassava and their involvement in abiotic stress-mediated responses. Planta. 2010;232:1251–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajji M, Kinet JM, Lutts S. The use of the electrolyte leakage method for assessing cell membrane stability as a water stress tolerance test in durum wheat. Plant Growth Regul. 2002;36:61–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1014732714549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bi H, Kovalchuk N, Langridge P, Tricker PJ, Lopato S, Borisjuk N. The impact of drought on wheat leaf cuticle properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:85. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti C, Gori A, Marino G, Latini P, Sobolev AP, Nardini A, Haworth M, Giovannelli A, Capitani D, Loreto F, Taylor G, Mugnozza GS, Harfouche A, Centritto M. Dynamic changes in ABA content in water-stressed Populus nigra: effects on carbon fixation and soluble carbohydrates. Ann Bot. 2019;124:627–643. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcz005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge A, Grieve TM, Jackson A, Thompson A, McCarty DR, Taylor IB. Characterization of the ABA-deficient tomato mutant notabilis and its relationship with maize Vp14. The Plant J. 1999;17:427–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernys JT, Zeevaart JAD. Characterization of the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family and the regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis in Avocado. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:343–354. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahad S, Bajwa AA, Nazir U, Anjum SA, Farooq A, Zohaib A, Sadia S, Nasim W, Adkins S, Saud S, Ihsan MZ, Alharby H, Wu C, Wang D, Huang J. Crop production under drought and heat stress: plant responses and management options. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1147. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi S, Kobayashi M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. A stress-inducible gene for 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis under water stress in drought-tolerant cowpea. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:553–562. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi S, Kobayashi M, Taji T, Naramoto M, Seki M, Kato T, Tabata S, Kakubari Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Regulation of drought tolerance by gene manipulation of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, a key enzyme in abscisic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2001;27:325–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Malladi A, van Iersel MW. Physiological and molecular responses to drought in Petunia: the importance of stress severity. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:6335–6345. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq J, Martin F, Sanier C, Clément-Vidal A, Fabre D, Oliver G, Lardet L, Ayar A, Peyramard M, Montoro P. Over-expression of a cytosolic isoform of the HbCuZnSOD gene in Hevea brasiliensis changes its response to a water deficit. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;80:255–272. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei W, Huang S, Tang S, Shui X, Chen C. Determination of abscisic acid and its relationship to drought stress based on cowpea varieties with different capability of drought resistance. Am J Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;12:79–85. doi: 10.3844/ajbbsp.2016.79.85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Nguyen KH, Chu HD, Ha CV, Watanabe Y, Osakabe Y, Leyva-González MA, Sato M, Toyooka K, Voges L, Tanaka M, Mostofa MG, Seki M, Seo M, Yamaguchi S, Nelson DC, Tian C, Herrera-Estrella L, Tran LP. The karrikin receptor KAI2 promotes drought resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1007076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Sun JK, Li CR, Lu ZH, Xia JB. Cloning and expression analysis of the FvNCED3 gene and its promoter from ash (Fraxinus velutina) J for Res. 2019;30:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s11676-018-0632-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Li H, Lv X, Ahammed GJ, Xia X, Zhou J, Shi K, Asami T, Yu J, Zhou Y. Grafting cucumber onto luffa improves drought tolerance by increasing ABA biosynthesis and sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20212. doi: 10.1038/srep20212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelle D, Huang B. Drought survival and recuperative ability of bentgrass species associated with changes in abscisic acid and cytokinin production. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2007;132:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nambara E, Marion-Poll A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:165–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirasteh‐Anosheh H, Saed‐Moucheshi A, Pakniyat H, Pessarakli M (2016) Stomatal responses to drought stress. In: Ahmad P (ed) Water stress and crop plants. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, West Sussex, pp 24–40

- Prabpree A, Sangsil P, Nualsri C, Nakkanong K. Expression profile of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and phenolic content during early stages of graft development in bud grafted Hevea brasiliensis. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;14:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2018.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Zeevaart JAD. The 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage reaction is the key regulatory step of abscisic acid biosynthesis in water-stressed bean. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15354–15361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao G, Devakumar A, Rajagopal R, Annamma Y, Vijayakumar K, Sethuraj M. Clonal variation in leaf epicuticular waxes and reflectance: possible role in drought tolerance in Hevea. Indian J Nat Rubber Res. 1988;1:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sangsil P, Nualsri C, Woraathasin N, Nakkanong K. Characterization of the phenylalanine ammonia lyase gene from the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) and differential response during Rigidoporus microporus infection. J Plant Prot Res. 2016;56:381–388. doi: 10.1515/jppr-2016-0056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanier C, Oliver G, Clement-Vidal A, Fabre D, Lardet L, Montoro P. Influence of water deficit on the physiological and biochemical parameters of in vitro plants from Hevea brasiliensis Clone PB 260. J Rubber Res. 2013;16:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Saradadevi R, Palta JA, Siddique KHM. ABA-mediated stomatal response in regulating water use during the development of terminal drought in wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1251. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathik MBM, Luke LP, Thomas M, Sumesh KV, Satheesh PR (2011) Identification of drought tolerant genes by quantitative expression analysis in Hevea brasiliensis. IRRDB International Rubber Conference, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- Seki M, Narusaka M, Ishida J, Nanjo T, Fujita M, Oono Y, Kamiya A, Nakajima M, Enju A, Sakurai T, Satou M, Akiyama K, Taji T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Carninci P, Kawai J, Hayashizaki Y, Shinozaki K. Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. The Plant J. 2002;31:279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BC, Schwartz SH, Zeevaart JAD, McCarty DR. Genetic control of abscisic acid biosynthesis in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12235–12240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Sathik MBM, Saha T, Jacob J, Schaffner AR, Luke LP, Kuruvilla L, Annamalainathan K, Krishnakumar R. Screening of drought responsive transcripts of Hevea brasiliensis and identification of candidate genes for drought tolerance. J Plant Biol. 2011;38:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Sathik MBM, Luke LP, Sumesh KV, Satheesh PR, Annamalainathan K, Jacob J. Stress responsive transcripts and their association with drought tolerance in Hevea brasiliensis. J Plant Crops. 2012;40:180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tint AMM, Sarobol E, Nakasathein S, Chaiaree W. Differential responses of selected soybean cultivars to drought stress and their drought tolerant attributions. Kasetsart J (natural Science) 2011;45:571–582. [Google Scholar]

- Volaire F, Thomas H, Bertagne N, Bourgeois E, Gautier MF, LeliÈVre F. Survival and recovery of perennial forage grasses under prolonged Mediterranean drought: II. Water status, solute accumulation, abscisic acid concentration and accumulation of dehydrin transcripts in bases of immature leaves. New Phytol. 1998;140:451–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1998.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LF. Physiological and molecular responses to drought stress in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;83:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZL, Huang B. Genotypic variation in abscisic acid accumulation, water relations, and gas exchange for Kentucky bluegrass exposed to drought stress. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2003;128:349–355. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.128.3.0349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Wu S, Ma F. Cloning and expression of two 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase genes during fruit development and under stress conditions from Malus. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:6795–6802. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3565-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang L, Zhang S, Zhu S, Wu P, Chen Y, Li M, Jiang H, Wu G. Global analysis of gene expression profiles in physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) seedlings exposed to drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0397-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]