Media is a collective term for various means of mass communication with the primary function of disseminating and receiving information. Television, radio, cinema, print, and internet are the sources through which people come to know what is happening around them. Due to the omnipresence of media, people absorb the received information and sometimes critically examine the received messages, using information received through multiple other sources. In short, the media constructs the belief, opinion, and attitude which facilitate social change.1, 2

Cinema is a powerful medium of building a public belief system, and when it comes to mental illness, cinema has always played and will keep playing a crucial role in disseminating knowledge and forming beliefs and attitude towards mental illness.3–6 Like international cinema, Hindi cinema also has an old relationship with mental illness. However, the depiction of mental illness in Hindi cinema has undergone several changes. During the 20th century, mental illness was misrepresented in the Hindi cinema.7–9 With the advent of media convergence, that is, the amalgamation of audiovisual and print media on digital platforms,10 Hindi cinema gradually portrayed a much more realistic picture of mental illness, but not wholly. Assuming the 20th century as a pre-media convergence period and focusing on the role of cinema in building the attitude and belief on the issue of mental illness, we analyze the portrayal of the same in Hindi cinema through the lens of production and representation in the pre-media convergence and post-media convergence eras. Subsequently, the article looks into the building up of the wrong conception in the mind of the audience regarding mental illness through the Hindi cinema. Further, it also tries to explore the factors responsible for the differences in the depiction of mental illnesses in pre- and post-media convergence periods.

Methodology

The authors have collected articles from websites such as ResearchGate and Google Scholar by using keywords such as “Indian Hindi Cinema,” “production,” “representation,” and “reception,” along with terms “health” and “mental illness.” Along with these, the authors have gone through different Hindi cinemas that used the mental illness concept. We selected such movies in which the protagonist is a sufferer or mental illness is used as a central theme, and we avoided the movies in which such characters were used as fillers or for making a comic scene.

An Introduction to Production, Representation, and Reception

Cinema involves three major processes starting from bringing the concept into reality to making of attitude, belief, and knowledge around it among people. These three processes, that is, production, representation, and reception, help us to understand the purpose and content and facilitate interpretation. While the first two are essential from the producer’s point of view, the last one delves into the audience’s point of view. How these three processes interplay in the context of media convergence is discussed further.

“Production” refers to building, creating, and executing the content through audio or audiovisual format. Clive11 extended and gave a more profound meaning to the word “production” and stated that it is the process of studying and observing the behavior of a producer of a media house. This process of media studies tries to learn the commercial environment of any media institution. Further, it peeps into the nature of the government’s and other corporate houses’ influence on media and how these media houses serve their interests.

“Representation” works with analysis and understanding of messages conveyed by the different forms of media. It tries to pick up the extent of subjectivity and forceful imposition of themes and to trace the formation and consequence of themes. With regard to mental health, studies on representation analyze the concerning actors such as medical professionals and patients with mental illness and the portrayal of treatment in cinemas and soap operas.11

“Reception” primarily deals with the nature of the involvement of the audience with the media. Theories give the foundation to reception and divide the view of the audience into passive and active. An article titled “media effect theory” has divided the media audience theories into four phases, starting with strong to mild influence on the audience.12 Among those theories, Lasswell’s “Magic Bullet Theory” labelled “audience” to be passive and receptive to whatever is thrown at them.13 “Individual Difference/Attitude Change Theory” claimed the audience to be active.14 Lowery gave insights on the gradual shift from blind faith to subjectivity and individuality in interpreting messages.15 This process envelops the stakeholders of the society who themselves are producers and representatives of the media. The “reception” process studies the layman’s response to health messages received through different media organs, their usage of those messages, and the impact it creates on their decisions regarding their health.

Production and Representation of Mental Illness by Hindi Cinema in Pre-media Convergence Era

The pre-media convergence era is a long period. One should not forget the varied pre-existing beliefs on mental illness causation, treatment, and outcome that were existing in the mid-20th century.16–26 The period marked dramatic advancement in Hindi cinema and pharmacotherapy for mental illness parallelly. Therefore, producers of the films captured and presented all popular ideas and beliefs on mental illness, such as incurable nature and miracle through religious rituals, in front of a receptive audience. This led to misunderstanding and common opinion on mental illness.27 Further, cinema makers audaciously generalized a single symptom as an entire mental illness. The symptom “retrograde amnesia” was used in the movies over three decades.28–30

The protagonist in such movies made during this period suffered from a mental disorder, and the story revolved around him or her. The person with mental illness is characterized as naive, careless, forgetful, destructive, childish, life-threatening, and incompetent. Several movies across the world have depicted the same symptoms of mental illness.31–36 Several studies across the world on movies have the same depiction of the sufferers.{30–35} Along with this, Indian Hindi Cinema relies a lot on the magicoreligious belief prevalent in our society as the cause and cure of mental illness.37, 38 Most of the movies relate mental illness with paranormal elements and depict mental health professionals as eccentric, weird, unprofessional, apathetic, holding grudges against the patient, and shaman in a white apron.37, 38

In movies, psychiatric treatments were shown as modes of punishment, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been presented as “electric shock” and a tool of torture, and psychotropic drugs have been portrayed with lots of dramatization and inaccuracy. Scientifically, ECT is one of the best measures of treatment and acts as a lender of the last resort for severe mental illness.39 However, it has been prominently used as a tool for creating insanity in movies.40–42 ECT in the films has been used by a negative character to erase memories or to bolster the insanity of the protagonist or supporting actor.43

Lobotomy (which is hardly in use as a treatment method for mental illness) has been depicted as a standard weapon for a psychiatrist to fulfill his/her grudge. Like in the movie Kyon Ki where the female protagonist’s father played the negative character of a psychiatrist and performed a lobotomy on the male protagonist as a punishment for loving his daughter, the female lead. Thus, the Indian Hindi cinema in the late 20th century and early 21st century minted money by solidifying the existing beliefs on mental illness.38

Why Such Representations?

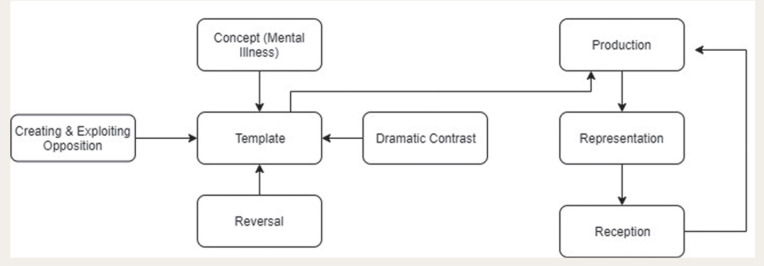

A study on reality television brought out the concept of people seeking entertainment out of “dramatized contrast,” such as people’s indulgence in movies that create anxiety and fear rather than security and pleasure. Therefore, portraying a person with mental illness as naive and violent sustains the dramatic effect.44

The overall impression over the audience through such a concept creates a “template.” The “template” is not a readymade construct applied by the producer. It is an existing notion about any object or subject among the viewers which is tested by program and film producers. If they get a favorable response from the viewers, they get encouraged to repeat them.45, 44 The movies are also fond of exploiting the possibilities of mental illness juxtaposed with the idea of “creating and exploiting opposition” such as good and evil, disaster and restoration, life and death, etc.46, 47 Especially in the case of life and death, a doctor is seen as a figure of paramount importance since he is the savior and possibly can also be Satan who can sabotage the lifeline. Such alteration of attributes associated with the character is the result of “reversal” applied by the production crew with the intention of unexpected representation of a psychiatrist as the villain to sustain the interest of the viewers.48 The psychiatrists shown in the intense hospital scene in most of the cinemas are placed with such a concept to get the desired effect of drama to meet the expectation of the audience. Hence, the unrealistic representation of mental illness in the Indian Hindi Cinema in the pre-media convergence era happened to sustain the interest of the audience.

As depicted in Figure 1, a template on mental illness was formulated, comprising the “concept,” “creating and exploiting opposition,” “reversal,” and “dramatic contrast.” The template was then sent to the production segment to represent mental illness through the Hindi cinema, followed by the positive receptivity of the audience, leading to the continuation of a model for production.

Figure 1. Production and Representation of Mental Illness by Indian Hindi cinema in Pre-Media Convergence Era.

Consequences of the Unrealistic "Representations"

Over the years, mental illness has supplied the Hindi cinema with engaging content. The sole motive was to amuse and surprise the viewers, but that resulted in the formation of wrong concepts on mental illness. As a result, the resentment of clinicians and academicians over the superficial content on mental illness grew gradually. The discourses among the clinicians and academicians were more concerned with the sufferers and their caregivers. Cinema gave very little insight on the sufferers and their caregivers and held the taboo associated with mental illness high. A taboo or formidable concept in society eventually results in stigma. Stigma, according to the Cambridge Dictionary, is “a strong sense of detachment or disapproval on something, which brings disgrace or shame.”49 Stigma persists because the family of the patient assumes that revealing the mental condition of their family member will harm their reputation in society.50–52 Though cinema took the topic for entertainment, it strengthened the existing belief on mental illness by showing that it has relations with black magic and ghosts, which had led to ignoring of a medical condition by people and also they often mistreated and still mistreat persons with mental illness. Studies have reported sufferers as being the victim of inhumane behavior by the general population and by family members.53–55 Further, they are labelled as life-threatening, criminal, aggressive, and violent, which is an act of boosting the prejudices, resulting in fear, anxiety, and stigma. A study reported that compared to people receiving information through print media, those who are frequently exposed to mental health issues through television and cinema are more intolerant towards a person with mental illness.56

As previously discussed, movies relate supernatural elements and magicoreligious beliefs with mental illness and spread stigma.57 Such depictions boost unscientific explanations and fear and provide people an additional excuse to alienate patients with mental illness from the community.58 Movies with such plot hamper and delay the treatment process as caregivers and patients themselves get pessimistic and perceive psychiatric treatment as a waste of time and attribute the causes of mental illness to paranormal phenomena.59 Hindi cinemas, by using the concept of “creating and exploiting opposition,” showed mental health professionals as “conspirators” and psychiatric treatment as a “conspiracy” to erase the memory or to make people insane and, in the process, deepened fears and prevented the public from approaching mental health professionals. Thus, mental health professionals are the victim of utopian concepts presented in the movies. Further, people believe that mental illness has a connection with paranormal elements and has no cure.

Production and Representation of Mental Illness by Hindi Cinema in Post-Media Convergence Period

The post-media convergence period marked a gradual shift in Hindi cinema from entertainment to infotainment. Popular movies gained the attention of not only the viewers but also the caregivers of people with mental illness.59–62 These movies have substantially portrayed different facets of mental illness such as dyslexia, Asperger’s syndrome, depression, and Tourette syndrome.

Dear Zindagi63 the story of an urban middle-class female suffering from depression, carefully brings scenes one by one where lifestyle adversities and flashback of childhood isolation put the protagonist into depression. The movie then advances by breaking stereotypical thoughts prevalent about patients with mental illness and the therapists. The movie is the first of its kind, which has correctly shown the therapeutic relationship between the mental health professional and the patient. A therapist, as a facilitator of the therapeutic process, comforts the client in a nondirective way than by giving advice or instructions.

On the other hand, title of the movie Judgementall Hai Kya was earlier Mental Hai Kya.64 That title was derogatory and invited widespread criticism from the professionals and public, which led to the change in the title. The movie, however, became an exception to the post-media convergence period and depicted the use of ECT without anesthesia, which is rarely done nowadays. Though the wrong diagnosis has been shown in Judgementall Hai Kya, the movie focused on psychotic symptoms and the protagonist beautifully executed those symptoms through her act. But the inaccurate representation of the symptoms suggests that the filmmakers have to do more thorough research on mental illness. Nevertheless, a hidden message that the film gave was that though a patient who has a chronic mental illness can make a family feel he or she is troublesome, bothersome, and a burden to them, the person can also be a helping hand in a few and important occasions. The protagonist’s uncle’s concern over regular intake of medication and frequent prompting also gives a positive message of family support system and adequate management of illness. Despite all the pros and cons, it has to be understood that producers solely do not make cinema to educate or to make people aware by serving accurate information. Scientists, health professionals, and educators are well aware of this fact.65

The cyberconnectivity led media convergence to make all organs of media portable, making information available through multiple sources. Therefore, reiterating the “unrealistic representation” will lead to monotony and gradual aloofness, which might hinder the minting of money by the producers. Because the producers are well aware of this, they have retired the existing “template” and applied the “twitch.”45, 48

“Twitch” is meant to sustain the unpredictability and the viewers’ interest.48 Kitzinger stressed to retire templates at regular intervals to combat the predicting ability of the viewers and predictability of the plots. 45 Today, the producers in Hindi cinema are focusing on the hardship of sufferers and their caregivers. With this change, they have now entered the niche segment of sufferers and caregivers. A few movies have shown the patients’ and their caregivers’ feelings such as agony, pain, and suffering and done well at the box office. This successful experimentation has led to the establishment of the new “template” for Hindi cinema. So, the current template projects mental health professionals as devoted to humanity and the protagonist from an ordinary background as successfully combatting life adversities and overcoming their disabilities.62, 63 This template is now successfully catering to the needs of the Hindi cinema. The overall discourse has been based on media-mental health from the psychosocial point of view. It is to be noted that Hindi cinema somehow managed to operate the same portrayal of a person with mental illness in the pre-media convergence era, which gives a hint of the dominant presence of the “Magic Bullet Theory” on the viewers.13 However, the post-media convergence era is witnessing the change in the template of the Hindi cinema. Thus, this transformation suggests the existence of the “Attitude Change Theory.”14

Due to the advent of various digital multimedia platforms, the audience is well informed prior to the release of a movie. Hence, the ongoing production through the existing template on mental illness is now unwelcomed by the audience (see Figure 2). Thus, the producers tend to retire the current template, and inclusion of the new template with a combination of “twitch” leads to the new model for representing mental illness in Hindi Cinema. In short, the producers are trying their hands on realistic representation of mental illness and need to be well informed and educated on the types of mental illness.

Figure 2. Production and Representation of Mental Illness by Hindi Cinema in Post-media Convergence Period.

Guidelines for Movie Making Concerning Psychiatric Issues

Sufficient exposure to signs and symptoms of any particular disorder seems necessary for scriptwriters and director before conceptualizing and finalizing the script.

Script finalizing in the presence of chosen representatives of different stakeholders, that is, caregivers, patients, and mental health professionals seems desirable. Incorporation of multiple opinions in the script will make it more sensible.

Though recent movies have particularly portrayed the hardships of the urban middle class, the struggle of the rural families and patients from lower strata is still absent from the silver screen. Therefore, filmmakers can utilize the opportunity to take up the issue of rural India and the rural people’s perspectives on mental illness.

Movies must not be made with an aim to label people with different kinds of mental illness. Instead, they should aim at informing and developing empathy. We need more social integration of people with mental illness, and movies are one of the important vehicles to do that.

Table 1 talks about the representation of psychiatry in pre- and post-media convergence periods. During the pre-media convergence era, the patient has been shown as troublesome, a burden to the family. The depiction of the psychiatrist as Mr Evil, unprofessional, insensitive, apathetic, and comic filler was prevalent in the pre-media convergence era. When it comes to treatment methods, psychotropic medicines were shown as ineffective, mostly harming the patient, or as a tool for erasing memory. Psychiatrist performing lobotomy, which is no longer the treatment of a patient with severe mental illness, has been shown in the movie Kyon Ki. A wrong depiction of ECT has also created a widespread stigma among the community.

Table 1. Representation of Psychiatry in Hindi Cinema.

| Representation of psychiatry in pre-media convergence era | |||

| Themes | Movies | Year | Identified characteristics |

| Portrayal of patient |

Khilona

Sadma Dilwale |

1970 1983 1994 |

Childish, naive, violent, destructive, ignorant, reckless, etc. |

| Portrayal of mental health professional (mainly psychiatrist) |

Damini Dilwale Kyon Ki |

1993 1994 2005 |

Apathetic, unprofessional, unscientific, used as comic fillers and boundary violators. |

| Portrayal of psychiatric

treatment (mainly psychotropic medicine, electro convulsive therapy and lobotomy) |

Khamoshi Damini Raja Kyon Ki |

1970 1993 1995 2005 |

Erasing of memories, tools of punishment. |

| Representation of psychiatry in post-media convergence period | |||

| Portrayal of patient |

Taare Zameen

Par My Name Is Khan Dear Zindagi Hichki |

2007 2010 2017 2018 |

Empowered, contributor to the community. |

| Portrayal of mental health professional |

Taare Zameen

Par Kartik Calling Kartik My Name Is Khan Dear Zindagi |

2007 2010 2010 2017 |

Empathetic, polite, sensitive, committed to help. |

| Treatment method |

Taare Zameen

Par Dear Zindagi |

2007 2017 |

Focused on one to one intervention, inclusion of other stakeholders like family, community, workplace, etc. |

On the other hand, though a handful, there have been movies in the post-media convergence period that beautifully depicted a patient’s struggle with self and also with society in which he or she lives and their accomplishments. The therapist is represented more sensibly, with attributes such as sensitivity, empathy, and concern for the patient’s well-being. The depiction of an overt and covert message that the family is important in the patient’s path of recovery is a great leap the Hindi cinema has taken in recent times.

Conclusion

The representation of mental illness is not as simple as it seems. As discussed earlier, through the production process of media studies, producers try to find out the perception of the viewers on any subject and represent what the majority of viewers think. In this way, they sustain the perception and earn out of it. However, cinema producers should also understand their fundamental duties prescribed in Article 51A(h) of the Indian Constitution to develop the scientific temper among the citizens. Though contemporary cinema has shown some progressive gestures in this direction, it will be more appreciable if the momentum of scientific temper could be maintained by serving the right information, especially on mental health and illness, without losing the entertainment quotient of the content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Philo G. Active audiences and the construction of public knowledge. Journal Stud; 2008; 9(4): 535–544. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Happer C, Philo G. The role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. J Soc Polit Psychol; 2013; 1(1): 321–336. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmerle J, Cress U. The effect of tv and film exposure on knowledge about and attitude towards mental disorder. J Community Psychol; 2013; 41(8): 931–943. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diefenbach DL. The portrayal of mental illness on prime-time television. J Community Psychol; 1997; 25: 289–02. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabbard GO, Gabbard K. Psychiatry and the cinema. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orchowski LM, Spickard BA, McNamara JR. Cinema and the valuing of psychotherapy: implications for clinical practice. Prof Psychol-Res Pr; 2006; 37: 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandramouleeshwaram S, Edwin NC, Rajaleelan W. Indie insanity—misrepresentation of psychiatric illness in mainstream Indian cinema. Indian J Med Ethics; 2016; 1(1): 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padhy SK, Khatana S, Sarkar S. Media and mental illness: relevance to India. J Postgrad Med; [serial online]. 2014; 60: 163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swaminath G, Bhide A. “Cinemadness”: in search of sanity in films. Indian J Psychiatry [serial online]. 2009; 51: 244–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakaveh S, Bogen M. Media convergence: an introduction. In: Jacko JA, ed. Human-computer interaction, HCI intelligent multimodal interaction environments. Berlin: Springer, 2007: 811–814. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seale C. Health and media: an overview. Sociol Health ill; 2003; 25(6): 513–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borah P. Media effects theory. In: Barnhurst KG, Ikeda KI, Maia RC. et al. , eds. The international encyclopedia of political communication. 1st ed. London: John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasswell HD. Propaganda technique in the world war. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co. Ltd, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan L. Applying an attitude change theory and a western media education instrument in the eastern setting. Med Psy Rev [n.a.]. 2008; 1(1): 15p. http://mprcenter.org/review/chanattitude-change/. Accessed November 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowery SA, DeFleur ML. Milestones in mass communication research: media effects. New York: Longman, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das S, Saravanan B, Karunakaran KP. et al. The effect of a structured educational intervention on explanatory models of relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a parallelly controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry; 2006; 188: 286–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James CC, Peltzer K. Traditional and alternative therapy for mental illness in Jamaica: patients’ conceptions and practitioners’ attitudes. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med; 2011; 9(1): 94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joel D, Sathyaseelam M, Jayakaran R. et al. Explanatory models of psychosis among community health workers in South India. Acta Psychiat Scand; 2003; 108(1): 66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med; 1978; 88: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulhara P, Avasthi A, Sharma A. Magical-religious beliefs in schizophrenia: a study from North India. Psychopathology; 2000; 33(2): 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nambi SK, Prasad J, Singh D. et al. Explanatory models and common mental disorders among patients with unexplained somatic symptoms attending a primary care facility in Tamil Nadu. Natl Med J India; 2002; 15(6): 331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poreddi V, Blrudu R, Thimmaiah R. et al. Mental health literacy among caregivers of persons with mental illness: a descriptive survey. J Neurosci Rural Pract; 2015; 6(3): 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangeeta SJ, Mathew KJ. Community perception of mental illness in Jharkhand, India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry; 2017; 27(3): 97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoonover J, Lipkin S, Javid M. et al. Perceptions of traditional healing for mental illness in rural Gujarat. Ann Glob Health; 2014; 80(2): 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scolari CA. Media evolution: emergence, dominance, survival and extinction in the media ecology. Int J Commun; 2013; 7: 24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorsdahl KR, Flisher AJ, Wilson Z. et al. Explanatory models of mental disorders and treatment practices among traditional healers in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2010; 13(4): 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson CA, Communities I. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. 2nd ed. London: Verso, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khilona. Directed by Vohra C. [film]. Mumbai: Prasad Production Pvt Ltd, 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadma. Directed by Mahendra B. [film]. Mumbai: R.S. Entertainment, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dilwale. Directed by Baweja H. [film]. Mumbai: S.P. Creations, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Psychology: the effects of media violence on society. Science; 2002; 295: 2377–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cutcliffe JR, media Hannigan B. Mass media, ‘monsters’ and mental health clients: the need for increased lobbying. J Psy Ment Health Nurs; 2001; 8: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diefenbach DL, West MD. Television and attitudes toward mental health issues: cultivation analysis and the third-person effect. J Community Psychol; 2007; 35: 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olstead R. Contesting the text: Canadian media depictions of the conflation of mental illness and criminality. Sociol Health ill; 2002; 24: 621–643. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Signorielli N. The stigma of mental illness on television. J Broadcast Electron; 1989; 33: 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahl OF, Roth R. Television images of mental illness: results of a metropolitan Washington media watch. J Broadcast; 1982; 26: 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ragini MMS 2. Directed by Patel B. [film]. Mumbai: Balaji Motion Pictures, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kyon Ki. Directed by Priyadarshan [film]. Mumbai: Orion Pictures, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S. et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT; 2004; 20: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damini. Directed by Santoshi R. [film]. Mumbai: Red Chillies Entertainment, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raja. Directed by Kumar I. [film]. Mumbai: Maruti International, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khamoshi. Directed by Sen A. [film]. Mumbai: Geetanjali, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swaminath G, Bhide A. “Cinemadness”: In search of sanity in films. Indian J Psychiatry; 2019; 51: 244–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill A. Fearful and safe: audience response to British reality programming. Telev New Media; 2000; 1(2): 193–113. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitzinger J. Media templates: patterns of association and the (re)construction of meaning over time. Media Cult Soc; 2000; 22(1): 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Labov W. Language in the inner city: studies in the Black English Vernacular. Philadelphia: University of Pennysylvania Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Propp VI. Morphology of the folktale. Austen: University of Texas Press, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langer J. Tabloid television: popular journalism and the “other news.” Oxon: Routledge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cambridge Dictionary [homepage on the internet]. Cambridge: Stigma, n.d. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/stigma. Accessed November 28, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magaña SM, Ramirez Garcia JI, Hernández MG. et al. Psychological distress among Latino family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: the roles of burden and stigma. Psychiat Serv; 2007; 58(3): 378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venkatesh BT, Andrews T, Mayya SS. et al. Perception of stigma toward mental illness in South India. J Fam Med Prim Care; 2015; 4(3): 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med; 2006; 11(3): 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choe JY, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Perpetration of violence, violent victimization, and severe mental illness: balancing public health concerns. Psy Serv; 2008; 59: 153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamperman AM, Henrichs J, Bogaerts S. et al. Criminal victimisation in people with severe mental illness: a multi-site prevalence and incidence survey in the Netherlands. Plos One; March 2014; 9(3): e91029, 13p. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0091029. Accessed November 26, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. et al. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry; 2005; 62(8): 911–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granello DH, Pauley PS, Carmichael A. Relationship of the media to attitudes toward people with mental illness. J Humanist Couns Educ Dev; 1999; 38: 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Das S, Doval N, Mohammed S. et al. Psychiatry and cinema: what can we learn from the magical screen? Shanghai Arch Psychiatry; October 2017; 29(5): 310–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson M. “One flew over the psychiatric unit”: Mental illness and the media. J Psy Ment Health Nurs; 2003; 10: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aina OF. Mental illness and cultural issues in West African films: implication for orthodox psychiatric practice. J Med Ethics; 2004; 30: 23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taare Zameen Par. Directed by Khan A. [film]. Mumbai: Amir Khan Productions, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.My Name Is Khan. Directed by Johar K. [film]. Mumbai: Dharma Productions, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hichki. Directed by Malhotra S.P. [film]. Mumbai: Yash Raj Films, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dear Zindagi. Directed by Shinde G. [film]. Mumbai: Red Chillies Entertainment, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Judgementall Hai Kya. Directed by Kovelamudi P. [film]. Mumbai: Balaji Motion Pictures, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naidoo J, Wills J. Health promotion: foundations for practice. London: Balliere Tindall, 2000. [Google Scholar]