Abstract

BACKGROUND

Scant research explores the association between women’s employment and fertility on a truly global scale due to limited cross-national comparative standardized information across contexts.

METHODS

This paper compiles a unique dataset that combines nationally representative country-level data on women’s wage employment from the International Labor Organization with fertility and reproductive health measures from the United Nations and additional information from UNESCO, OECD, and the World Bank. This dataset is used to explore the linear association between women’s employment and fertility/reproductive health around the world between 1960 and 2015.

RESULTS

Women’s wage employment is negatively correlated with total fertility rates and unmet need for family planning and positively correlated with modern contraceptive use in every major world region. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that these findings hold for nonagricultural employment only.

CONTRIBUTION

Our analysis documents the linear association between women’s employment and fertility on a global scale and widens the discussion to include reproductive health outcomes as well. Better understanding of these empirical associations on a global scale is important for understanding the mechanisms behind global fertility change.

1. Introduction

There have been dramatic global transformations in women’s status around the world in recent history. One particularly striking transformation has been global changes in women’s labor force participation, which has increased around the world over the last century (ILO 2018a).3 Globally, women make up about 40% of the world’s workforce, including an increasing number of women in low- and middle-income countries, especially in agriculture, manufacturing, and service sectors (ILO 2015). Over a similar time period, there have also been important changes in global fertility patterns, including falls in total fertility rates (TFRs) in most major regions of the world (de Silva and Tenreyro Forthcoming; Dorius 2008; Morgan 2003; Wilson 2001). Estimates suggest that global TFR fell from about 5 in 1960 to just under 2.5 in 2015, representing a staggering transformation in global fertility trends (de Silva and Tenreyro Forthcoming).

Given that both employment and fertility are intimately tied to women’s economic and social statuses in families and societies, there has been enormous interest in the correlation between women’s employment and fertility. In high-income countries, the negative correlation between women’s wage employment and fertility has been well documented (Ahn and Mira 2002; Bernhardt 1993; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Moen 1991; Waite 1980), although there has been some evidence of a reversal in these trends in some contexts in recent decades due to adoption of policies that reconcile employment and family conflict (Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Rindfuss and Brewster 1996). There has been less research overall on the employment–fertility correlation in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries, perhaps due to the enormous heterogeneity in prevalence and type of employment across these contexts. In one notable exception, Bongaarts and colleagues document a negative association between having children at home and women’s employment in low- and middle-income countries, albeit with heterogeneity by region and type of employment (Bongaarts, Blanc, and McCarthy 2019). For example, employment in agriculture has close to a null relationship with having children at home, but employment in transitional sectors (e.g., household/domestic service) or modern sectors (e.g., professional, managerial, clerical) is negatively associated with the number of children at home.

To the best of our knowledge, there is limited to no work that explores the correlation between women’s employment and fertility on a truly global scale. In part, this lack of global exploration on the topic is due to data constraints, since it is difficult to find cross-national comparative standardized information about employment, fertility, and reproductive health in survey data across high- and low-income contexts. For example, standardized IPUMS census micro-data contain information about current employment and children residing in the household but not total fertility or reproductive health outcomes. Other commonly used cross-national data sources – such as the Luxemburg Income Study or Demographic and Health Surveys – are only available for a subset of countries that are typically at similar levels of socioeconomic development. Furthermore, because measures vary substantially across surveys, it is challenging to find standardized measures of women’s employment, including both salaried employment and informal piecemeal employment, the latter of which is particularly common in low- and middle-income countries (ILO 2018b).

This paper compiles a unique global dataset that combines nationally representative data on women’s wage employment from the International Labor Organization (ILO) with fertility measures from the United Nations (UN) and additional information from UNESCO, OECD, and the World Bank. All our analyses are conducted at the country level and thus explore aggregated – and not micro-level – associations between employment and fertility/reproductive health. The advantage of using aggregated data is that the experience of living in a country where many women are employed may have important spillover effects even among unemployed women, and these may be captured in our analyses. For example, high levels of women’s employment in a society may correspond with broader sociocultural shifts in norms about gender, fertility, and fertility regulation even among women who are not employed but who are exposed to new role models, norms, and ideas by seeing other women in the public sphere.

In what follows we highlight dominant approaches that have been used to understand the associations between women’s employment and fertility/reproductive health in literature from high- and low-income countries. Although these explanations sometimes focus on a unidirectional relationship (e.g., the effects of fertility on employment or the effects of employment on fertility), we emphasize that this relationship could run in either direction (or both). Next we explore the linear associations between women’s wage employment and TFR at the country-level from 1960 onward for four major world regions, encompassing both high-, middle-, and low-income countries. Because women’s abilities to regulate their fertility via modern contraceptive methods could be an important cause and consequence of their entrance into the labor force, we also explore the linear associations between women’s modern contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning. In doing so, our analysis widens the discussion of the fertility and employment correlation to include reproductive health outcomes beyond fertility. Finally, we explore the linear associations between employment and TFR, contraceptive use, and unmet need for family planning, disaggregating by whether or not the employment is in the agriculture sector, thus providing insight into whether the type of employment matters for these linear associations. Although we are not able to estimate causal impacts in this paper, descriptive associations are nonetheless important for furthering understandings of the relationship between employment and fertility across diverse global settings.

2. Approaches to the employment–fertility correlation

2.1. The incompatibility approach

The dramatic expansion of women’s labor force participation in high-income countries in the last century represented a major change in women’s status within families and societies and corresponded with important shifts in fertility and family formation (Goldin 1995, 2006). A fairly extensive body of literature has examined the premise that the incompatibility between employment and child-rearing leads to reductions in fertility (Brinton and Lee 2016; McDonald 2000b, 2006), reductions that in some cases have led to the lowest fertility levels documented in several European contexts (Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Kohler, Billari, and Ortega 2002). Although this approach sometimes assumes that that employment will affect fertility decision-making, women’s abilities to regulate and lower their fertility are also important precursors to their employment (Aguero and Marks 2008; Angrist and Evans,1998; Bailey 2006; Bloom et al. 2009; Cáceres-Delpiano 2012; Cruces and Galiani 2007; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1980). For example, it has been shown that the introduction of hormonal birth control was important for expanding women’s labor force participation in the United States (Bailey 2006; Goldin and Katz 2002).

The incompatibility hypothesis hinges on the nature of employment in industrialized economies. The idea is that in industrialized economies, unlike other economies, employment and moneymaking activities are more incompatible with child-rearing because they take place outside the house and under a time schedule that is more inflexible than employment performed in the house (Stycos and Weller 1967; Weller 1977). The implication is that women’s employment is compatible with high fertility in preindustrial agricultural settings but less so in industrialized economies. At the individual level, research in high-income countries shows that women who are employed have fewer children that women who are not employed (Spain and Bianchi 1997). Furthermore, pursuing a career tends to delay the onset of fertility for logistical or social reasons, which ultimately lowers completed fertility (Rindfuss and Brewster 1996).

At the aggregate level, the incompatibility hypothesis suggests that there should be lower levels of fertility in countries with higher levels of women’s employment. Studies show, however, that the translation of the individual-level mechanism to the aggregate level is not always straightforward. Research in high-income countries shows that high levels of women’s employment have been correlated with lower fertility in the past, but in recent decades there has been a positive association between levels of women’s employment and fertility in some contexts (Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Rindfuss and Brewster 1996). The main explanation developed to account for this reversal and the compatibility/coexistence of very high levels of employment and relatively “high” fertility has focused on social policy and institutions, and changes in gender relations. On the one hand, countries might set up institutions that reduce some of the incompatibilities between employment and child-rearing (e.g., parental leave, child-care centers, part-time and flexible employment) (Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård 2015). At the same time, changes in gender relations that result in men’s increased involvement in child-rearing might similarly reduce the negative association between employment and fertility. Nonetheless, the relationship between institutions and changes in gender relations is partly endogenous, as certain forms of social policy can trigger changes in gender relations and shifts in gender relations can increase demand for institutional change.

Of course, there is considerable complexity in the social meanings of employment, and these may change over time as women’s economic opportunities are transformed by changing social and economic circumstances. For example, as more and more women join the labor force, increasing numbers of women may come to see employment as a viable possibility, thus leading to higher opportunity costs for childbearing and lower preferences for fertility (Becker and Lewis 1974). At the same time, increases in women’s labor force participation at the national level may change women’s perceptions about the possibility or acceptability of working while a child is young (particularly if there are family policies that help facilitate work–family incompatibilities), which could actually lead women to perceive lower opportunity costs and higher childbearing desires. Whether or not increases in women’s labor force participation lead women to perceive higher or lower opportunity costs to childbearing may be heterogenous across contexts and may depend on the starting level of women’s employment in society. Furthermore, this may change over time as policies and norms also change.

Although the incompatibility approach is typically applied to industrialized settings where women are employed outside the home, it could also be useful in low-income preindustrial settings where women must simultaneously balance many different types of paid and unpaid labor. For example, a randomized control trial in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya, found that subsidized child care led to significant increases in poor urban women’s employment (Clark et al. 2019). This finding runs counter to the assumption that women’s child-care responsibilities are not obstacles to their employment in low-income preindustrial settings, where women are assumed to have more flexibility and nearby family to help. This suggests that incompatibility may be a more important part of the fertility–employment explanation than is often considered in low-income settings where women engage in paid employment in both formal and informal situations.

2.2. The empowerment approach

Another approach suggests that earned income is an important determinant of women’s autonomy; thus women’s employment is an important form of economic empowerment that is important for fertility reduction (Upadhyay et al. 2014; Upadhyay and Hindin 2005). Although there has been debate on what exactly empowerment entails (Kabeer 1999), it has been a widely utilized concept in research on low-income contexts. The idea underlying this approach is that women’s employment can lead to a radical transformation in their options for economic survival and their bargaining power within families, including the ability to advocate for their own fertility desires (Anderson and Eswaran 2009; Duflo 2012; Narayan-Parker 2005). Just as the opening of jobs for young men lowers fathers’ patriarchal power over them (Ruggles 2015), women’s employment reduces their dependency on family ties (including fathers as well as husbands) by providing them with independent sources of income.

In contexts where women’s lack of choice over their reproduction is part of a broader patriarchal regime, where women often also lack access to reproductive health care, contraceptives, and abortion (Barber et al. 2018), women’s increased financial resources could give them more bargaining power to advocate for their reproductive preferences (Allendorf 2007; Beegle, Frankenberg, and Thomas 2001; Behrman 2017; Doss 2005; Quisumbing and Maluccio 2003). In further support of this, there is evidence linking women’s economic autonomy (measured as access to paid employment or micro-credit loans) to higher family planning use in South Asia (Dharmalingam and Morgan 2004; Schuler, Hashemi, and Riley 1997). At the same time, the reverse may be true as well, as increased access to reproductive control and lowered fertility may empower women in new dimensions, including by allowing them to enter the wage labor market.

Nonetheless, women’s employment is not always empowering, particularly given the considerable heterogeneity in types of employment women perform across contexts. Many women around the world are employed in the informal economy in jobs that lack security or stability and are physically and mentally strenuous (ILO 2018b). Many women are also disadvantaged in maintaining control over employment-related resources and earnings (Ferber, Green, and Spaeth 1986). Throughout low- and middle-income countries, the proportion of women engaged in informal employment is higher than the proportion of men, which has implications for women’s abilities to obtain and negotiate for decent income and safe labor conditions.4 In many regions – including South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa – a considerably higher proportion of women’s employment than men’s employment is concentrated in agriculture (ILO 2015) because men have left agriculture to pursue better opportunities in service and manufacturing sectors. Informal and/or poorly paid jobs (which are in many regions concentrated in agriculture) may be less effective at changing women’s preferences or bargaining abilities because the women holding these jobs lack financial security and/or personal autonomy.

It is also plausible that only jobs that take women outside the direct patriarchal authority of male relatives are effective at increasing women’s autonomy. For example, Anderson and Eswaran (2009) find that employment does not inherently lead to increased women’s autonomy in Bangladesh. Rather, employment needs to be outside of husbands’ farms to positively affect female autonomy outcomes. This is relevant because around the world, a disproportionate share of women also can be considered “contributing family workers” (e.g., employed in a market-oriented enterprise owned by a household member) (ILO 2016). This is particularly the case in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia, where the percentage of women who are contributing family workers exceeds that of men by 18 percentage points and 23 percentage points, respectively (ILO 2016).

Although the empowerment approach has primarily been applied to low-income countries where many women are entering the labor market for the first time, there are aspects of the empowerment perspective that could be useful for high-income countries as well. Policy makers often assume that incompatibility between child-rearing and employment is the main cause of low fertility in high-income settings. While policies that promote work–family balance can indeed have important social benefits, the introduction of generous family policy is not a panacea for low levels of fertility (Chesnais 1996; Hoem 1990; McDonald 2006). This could reflect that men’s care burden has been slow to change in many contexts, but it could also speak to the fact that the wide-scale entrance of women into the labor market has led to broader changes in values and norms about desired childbearing. Women might want fewer children (at least partially) not just because of incompatibility but because they find social meaning in other aspects of life outside of motherhood and have the resources to realize their goals (Blackstone and Stewart 2012).

3. Data, measures, and methods

3.1. Data

We draw on multiple sources to construct a unique global time-series dataset on women’s employment, fertility, and reproductive health trends for low-, middle-, and high-income countries. All measures and analyses are conducted at the country level, and we strive to include as many country-years as possible. Data on employment are taken from the International Labor Organization; data on fertility and reproductive health are taken from Global UN; and data on economic and schooling conditions are taking from UNESCO, OECD, and the World Bank (via the World Bank data archive). Our current sample focuses on adult populations and includes 174 countries ranging across the years 1960–2015, representing 89% of the 195 countries in the world. Table 1 presents a summary of key measures by region. Our dataset has information on most of the largest countries in the world (including China, India, the United States, and Brazil). We present estimates for the pooled global sample and also aggregate countries into four major regions: (a) Europe, United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (which for simplicity we refer to as Europe/North America), (b) Latin America, (c) Africa, and (d) Asia. The regions are grouped using a modified version of the UNSD M49 region code, although for reasons of linguistic and sociocultural similarity we include Australia and New Zealand with the United States and Europe rather than Asia. Appendix Table A-1 lists countries included in each region.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics

| Women’s employment rate | Total fertility rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N countries | Mean value | Mean # observations (min.–max.) | Mean value | Mean # observations (min.–max) | |

| Total | 174 | 53.2 | 40.0 | 3.7 | 50.9 |

| (1–59) | (19–56) | ||||

| 1: Europe/North America | 42 | 64.4 | 47.8 | 1.7 | 55.2 |

| (8–59) | (43–56) | ||||

| 2: Latin America | 32 | 46.7 | 42.8 | 3.2 | 51.5 |

| (1–59) | (23–56) | ||||

| 3: Africa | 48 | 55.1 | 33.1 | 5.7 | 48.8 |

| (1–59) | (28–56) | ||||

| 4: Asia | 52 | 46.0 | 38.8 | 3.6 | 49.1 |

| (4–59) | (19–56) | ||||

Sources: IPUMS International, ILO, DHS, LIS, UN Population.

Notes: See Appendix Table A-1 for the list of countries included in each region.

3.2. Measures

Women’s employment

Women’s employment is a central measure in our analysis because it has long been hypothesized to be both a cause and a consequence of fertility change. We measure women’s employment using ILO data on the employment-to-population ratio for women, which is calculated by dividing the number of women employed by the number of women in the working-age population (i.e., aged 15–65) and multiplying by 100. The ILO defines the employed as “all persons of working age who during a specified brief period, such as one day or one week, were in the following categories (a) paid employment (whether at work or with job but not at work); or (b) self-employment (whether at work or with an enterprise but not at work)” (ILO 2019). Typically, the working-age population is 15 to 65, although there is some country-level variation in what is considered working age. A high ratio of employment to population means that a large share of the population of working-age women is employed, whereas a low ratio of employment to population means that a large share of the population of working-age women is either unemployed or out of the labor market. ILO estimates are based on country labor force surveys. For detailed information on ILO’s standardization process. see Bourmpoula, Kapsos, and Pasteels (2016).

Employment is highly heterogenous (i.e., there are differences in skill sets, compensation, levels of formality, and so on), so we also explore whether the type of employment matters for the employment–fertility correlation. Because available literature suggests that the central fissure is between agricultural and nonagricultural employment (particularly in low- and middle-income countries) (Bongaarts, Blanc, and McCarthy 2019), we also conduct analyses with alternative employment measures (also taken from the ILO) that capture women’s employment in agricultural versus nonagricultural activities. The measures are the share of women employed in agriculture over all women employed, and the share of women in nonagriculture over all women employed. Linear interpolation is used for country-years with missing values in both employment variables.5 Because not all countries have agricultural employment data, as a robustness check, we rerun all our main models, restricting the sample to the countries that do have agricultural data; results are substantively the same and are available upon request.

Fertility

Fertility is hypothesized to be important because employment might lead women to lower their childbearing (due to incompatibility, empowerment, or some combination of both) or because lowered childbearing allows women to seek employment. In our analysis, fertility is measured as the TFR in any given year. The TFR is a synthetic measure of fertility that approximates the number of children a woman would have if she were to experience age-specific fertility levels in a given year. It is important to note that TFR is age standardized (other measures used in this analysis are not). TFR data come from UN Population (2017). The UN calculates the TFR using data from civil registration systems, household surveys, and censuses.6 Linear interpolation is used for country-years with missing values of this variable using the same strategy as described above.

Modern contraceptive use

Modern contraceptive use is an important proximate determinant of fertility: Increased usage of modern contraception might allow women to seek employment. Alternatively, employment might lead women to adopt modern contraceptive measures by providing them with the financial autonomy necessary to access contraceptives or the motivation to regulate conception. Modern contraceptive use could be an active choice of women who want to regulate fertility, but women may also use modern contraceptives with limited volition at the instruction of partners, medical professionals, or NGO workers. Modern contraceptive use is measured as the proportion of women of reproductive age (15–49) who report current use of any modern contraceptive methods, including oral contraceptive pills, implants, injectables, intrauterine devices, male condoms, female condoms, male sterilization, female sterilization, lactational amenorrhea, and emergency contraception. These estimates are taken from UN Population and are calculated using nationally representative survey data (Kantorova 2019).

Unmet need for family planning

Unmet need for family planning is an important measure of whether women want to stop or limit childbearing but are not using modern methods, presumably due to factors such as lack of access or knowledge. This is relevant because employment might lead to lower unmet need for family planning if employment corresponds with women’s autonomy and control over resources. At the same time, low unmet need for family planning might also lead to higher women’s employment because women are confident they can regulate fertility in ways that allow them to pursue paid employment without interruption. Although unmet need for family planning is related to modern contraceptive use, it is conceptually distinct because it captures unrealized needs, whereas contraceptive use captures actual usage (although usage might be determined by oneself or another person). Unmet need is measured in accordance with international standards as the proportion of women of reproductive age (15–49) who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using a modern method of contraception.7 These estimates are taken from UN Population and are calculated using nationally representative household survey data (Kantorova 2019).

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is important because underlying economic conditions are likely correlated with both women’s employment opportunities and their fertility outcomes. GDP could also be causally intermediate, because expanded women’s work might impact GDP, which in turn might impact fertility. GDP is a time-varying country-level measure of economic conditions that is calculated in current US dollars and is retrieved from the World Bank based on calculations using World Bank national accounts data and OECD national accounts data.

Schooling

Schooling is positively correlated with both women’s labor force participation and negatively correlated with women’s fertility. Schooling is measured by the school enrollment secondary (gross) gender parity index (GPI). GPI is calculated as the ratio of girls to boys enrolled at the secondary level in public and private schools. A GPI of less than 1 suggests that girls have a disadvantage in secondary education, and a GPI of greater than 1 suggests that girls have an advantage in secondary education. GPI is retrieved from the World Bank and based on data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. As a robustness check, we rerun all models, substituting GPI with a measure of the percent of women who completed secondary education; this measure is retrieved from the World Bank using data from UNESCO. We do not include secondary education in our main models because we lose about 800 observations from 20 countries due to missing data on this measure (although all general patterns are robust to including this measure).

3.3. Methods

We start by graphing country-level trends in employment and TFR to provide a descriptive overview of how employment and fertility are changing globally. As a next step, we assess the linear associations between country-level women’s employment and TFRs (including country fixed effects). Because the relationship between employment and fertility is likely bidirectional – employment might influence fertility, but fertility could also influence employment – our estimates capture a linear association but with no assumptions about directionality. (In other words, we make no assumptions about whether women’s employment affects fertility or vice versa.8) We run these models for a pooled global sample of all countries in our analysis and disaggregated by the four regions. While the estimates we use are representative at the country level (using country weights when appropriate), because country-years are the main units of the main analysis, we do not weight by country size when pooling countries in the regional and global analyses. Instead, we treat each country equally, which ensures that changes in employment/fertility in large countries do not disproportionately affect our pooled estimates. This strategy has been employed by others conducting similar analyses (Pesando et al. 2019).

Changes in both women’s employment and fertility likely correspond with myriad other social and economic changes. Thus, as a supplement, we also run a second set of models where we include controls for time-varying country-level factors such as GDP and GPI. Because there are many unobserved time-varying factors not included in our models (e.g., population age structures, governmental or policy changes, patterns of internal or external migration), it is important to emphasize that these analyses capture associations and not causal effects.

The literature suggests that the type of employment is consequential for fertility outcomes and that only certain types of employment (such as nonagricultural, salaried, and outside the family) might be correlated with women’s financial autonomy and/or fertility and reproductive health outcomes (Anderson and Eswaran 2009; Finlay 2019). Given this, we also run models where we disaggregate the correlations by agricultural versus nonagricultural employment.

Because women’s ability to regulate their fertility via modern contraceptive methods could be an important cause and consequence of entrance into the labor force, we also explore the linear associations between women’s unmet need for family planning and modern contraceptive use, using the same empirical strategy. This provides a fuller analysis of the association between women’s employment and reproductive health beyond just fertility.

While the age ranges for the variables of interest differ (employment measures are calculated for the working-age population of 15 to 65, and contraception measures are calculated for the reproductive age population of 15 to 49), we do not necessarily see this as a limitation, since we use aggregated measures of these variables. For example, it is plausible that women in the reproductive years may be influenced by large numbers of older women who are still employed. By including country fixed effects, we make sure that the estimates are an average of within-country variation in associations between employment and fertility/reproductive health, but these estimates do not draw on between-country differences in other characteristics, such as population age structure.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results: Women’s employment and fertility in a global perspective

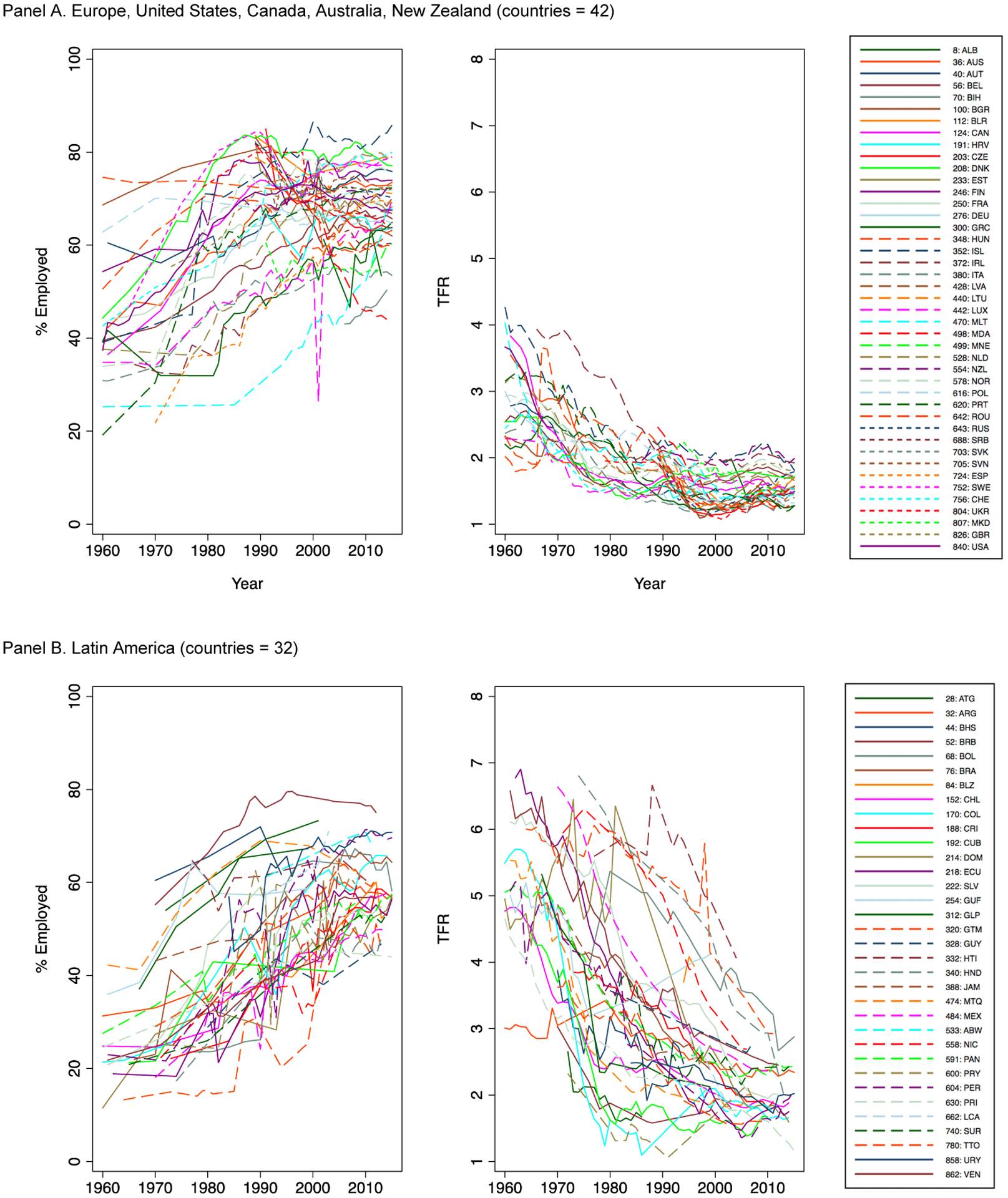

Figure 1 shows women’s employment and total fertility rates for all country-years by geographic region. Despite variation in levels and trends, these descriptive results overall suggest both increasing women’s employment and declining fertility across regions. Panels A and B (Europe/North America and Latin America) show this pattern most clearly, while Panels C and D (Africa and Asia) display more heterogeneity.

Figure 1:

Global employment and fertility trends, 1960–2015

Source: Created by the authors using data from ILO and UN.

Panel A (Europe/North America) shows the well-known increase in women’s employment, which begins as early as the pre-1960s for some countries and as late as the 1980s for others. These changes in employment coincide with moderate but meaningful declines in fertility, as fertility levels drop well below replacement levels. Our data also show a timid rebound in total fertility in the 2000s, which other researchers have used to suggest that shifts in policies and gender norms can work to mitigate the incompatibility between employment and fertility (Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård 2015). Panel B, on Latin America, also shows striking increases in women’s employment and declines in fertility levels. Unlike Panel A, however, declines in fertility begin from much higher levels and do not generally drop below replacement levels in most places. The overall increase in women’s employment in this period is comparable to that experienced in high-income countries (Panel A), although the overall levels are generally lower.

Panels C and D show trends in Africa and Asia. Employment levels and trends are highly heterogeneous in both regions. In Africa, women’s employment rates are generally flat. Some countries have high employment rates (such as Malawi and Kenya, at 70%), while others have very low employment rates (such as Egypt and Algeria, at about 10%–25%). The enormous heterogeneity in Africa likely reflects that many employment opportunities in Africa are informal and piecemeal in nature (e.g., agricultural labor and selling in markets) (Al Samarrai and Bennell 2007; Hino and Ranis 2014). In Asia, employment rates are similarly varied, which also likely reflects the high level of informal and often precarious labor. Nonetheless, there are small increases over time in women’s employment, which could reflect rises in female-oriented service and manufacturing jobs and also rising urbanization. Fertility trends in Africa and Asia are also heterogeneous. Most countries show moderate declines, although fertility levels vary greatly. For instance, in Cape Verde, the total fertility rate drops from 6.2 to 2.3 between 1978 and 2013, whereas in Cameroon, drops were more moderate (e.g., from 6.6 to 5.7) over a similar period. Nonetheless, the overall high levels of fertility and the great heterogeneity in levels of women’s employment mean the correlation between women’s employment and fertility is less clear in these two regions.

4.2. Linear associations between women’s employment and TFR

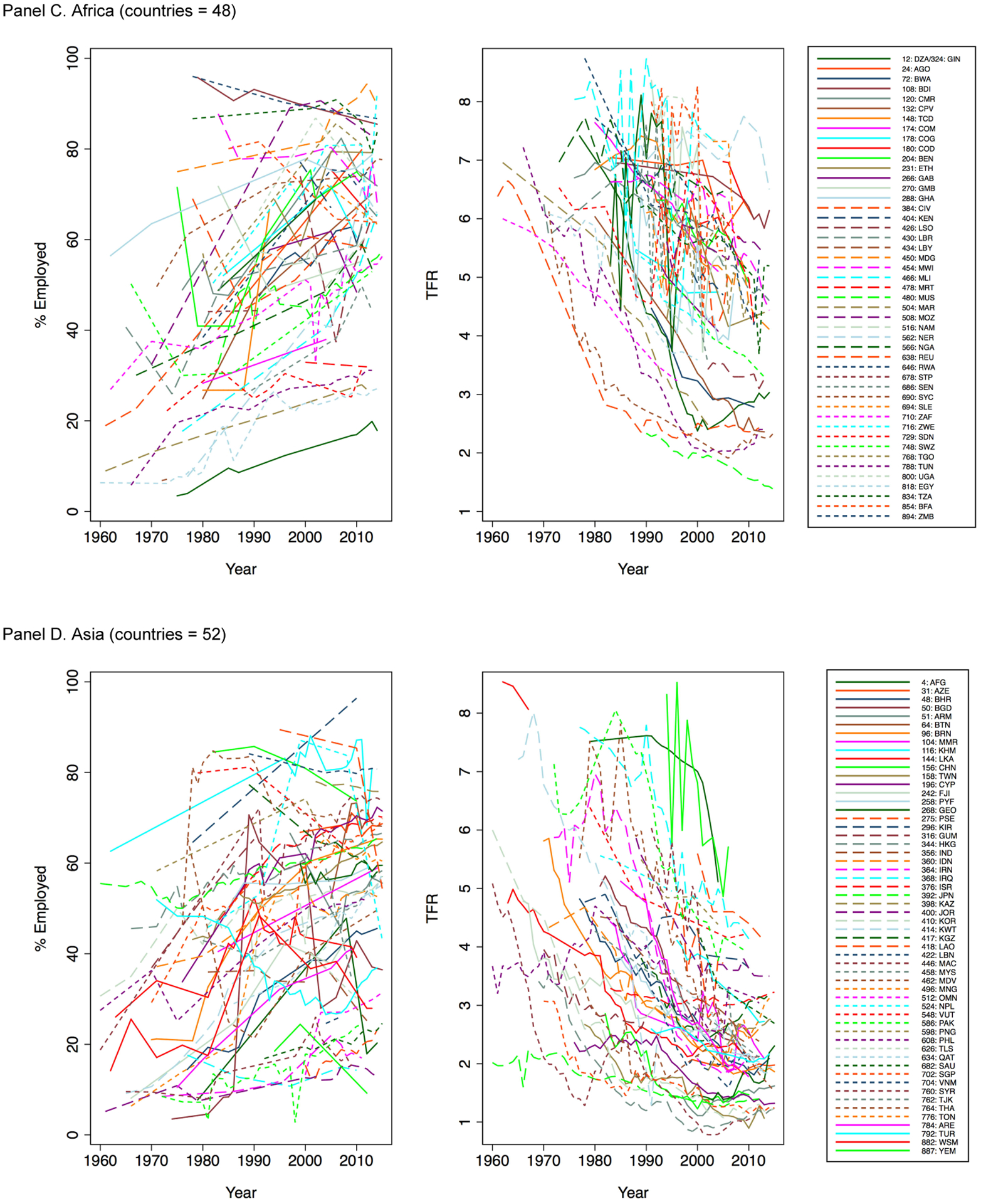

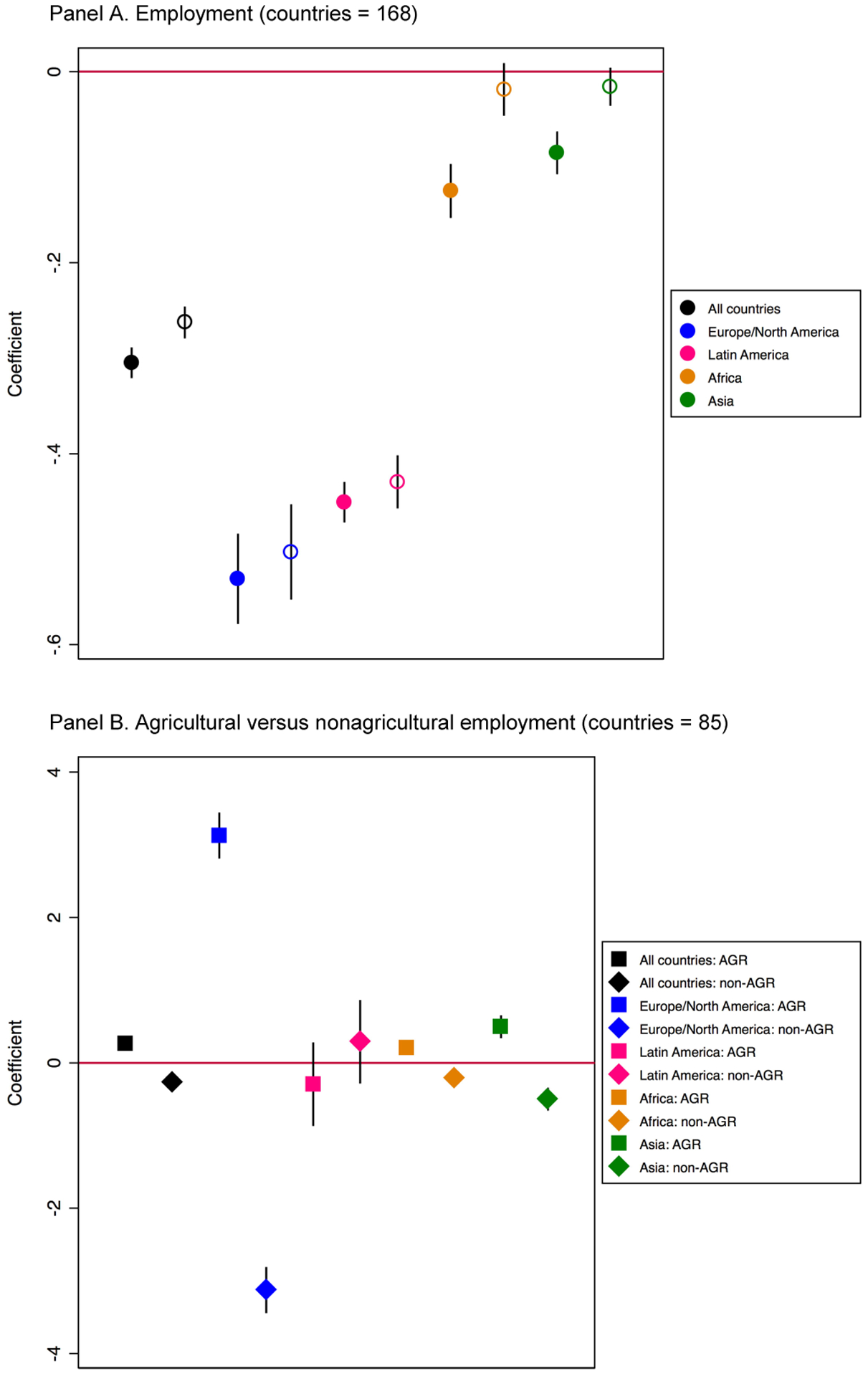

The preceding section showed descriptive evidence that women’s employment increased, and fertility decreased, in all four major world regions, albeit with within-region heterogeneity. In Figure 2, Panel A reports results from regressions that test for a statistically significant linear association between women’s wage employment and TFR at the country level. Our main model, Model 1, adjusts only for country fixed effects and is represented by the solid dot. Model 2 includes controls for GDP and GPI and is represented by the hollow dot. We run Models 1 and 2 for the pooled sample of all countries and for each of the four regions in our analysis. We present results as a series of figures; corresponding regression tables can be found in Appendix Tables A-2 to A-7.

Figure 2:

Linear association between wage employment and TFR with country fixed effects (1960–2015). Panel A shows the empty model (solid dots) and the model with controls for GDP and GPI (hollow dots). Panel B disaggregates by agricultural versus nonagricultural employment.

Source: Created by the authors using data from ILO, UN, and World Bank.

In the pooled estimates – represented by the black dot – there is a statistically significant negative association between women’s employment and TFR in both Model 1 and Model 2. When we disaggregate by region, we see there is a negative association between employment and TFR in all four regions. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the employment–fertility correlation is considerably smaller in Europe/North America – represented by the solid blue dot – than in the other three world regions, which may reflect more work–family reconciliation policies in this region. The larger confidence intervals on the point estimates for Latin America (pink), Africa (orange), and Asia (green) compared to Europe/North America likely reflect the larger heterogeneity in levels of women’s employment and TFRs across contexts in these regions. Including controls for GPI and GDP in Model 2 does little to alter the magnitude or the significance of coefficients for Europe/North America or Latin America. In Africa and Asia, the magnitude of the employment–fertility correlation becomes smaller upon adding these controls (though it retains statistical significance).

In Figure 2, Panel B presents results of the linear association between women’s employment and TFR, disaggregating by agricultural employment versus nonagricultural employment. In the pooled model of all regions, women’s agricultural employment is positively associated with TFR (black square), but women’s nonagricultural employment is negatively associated with TFR (black diamond). The general pattern of a positive correlation between agricultural employment and TFR and a negative correlation between nonagricultural employment and TFR is echoed in the region-specific analyses, although not all of these coefficients are statistically significant at p < 0.05. This may be due to reduced sample sizes for the agricultural/nonagricultural employment analysis, which falls from 174 countries to 85 countries in the pooled analysis due to less data about type of employment being available in many countries. This may limit statistical power, particularly in the region-specific analyses, where samples fall even further.

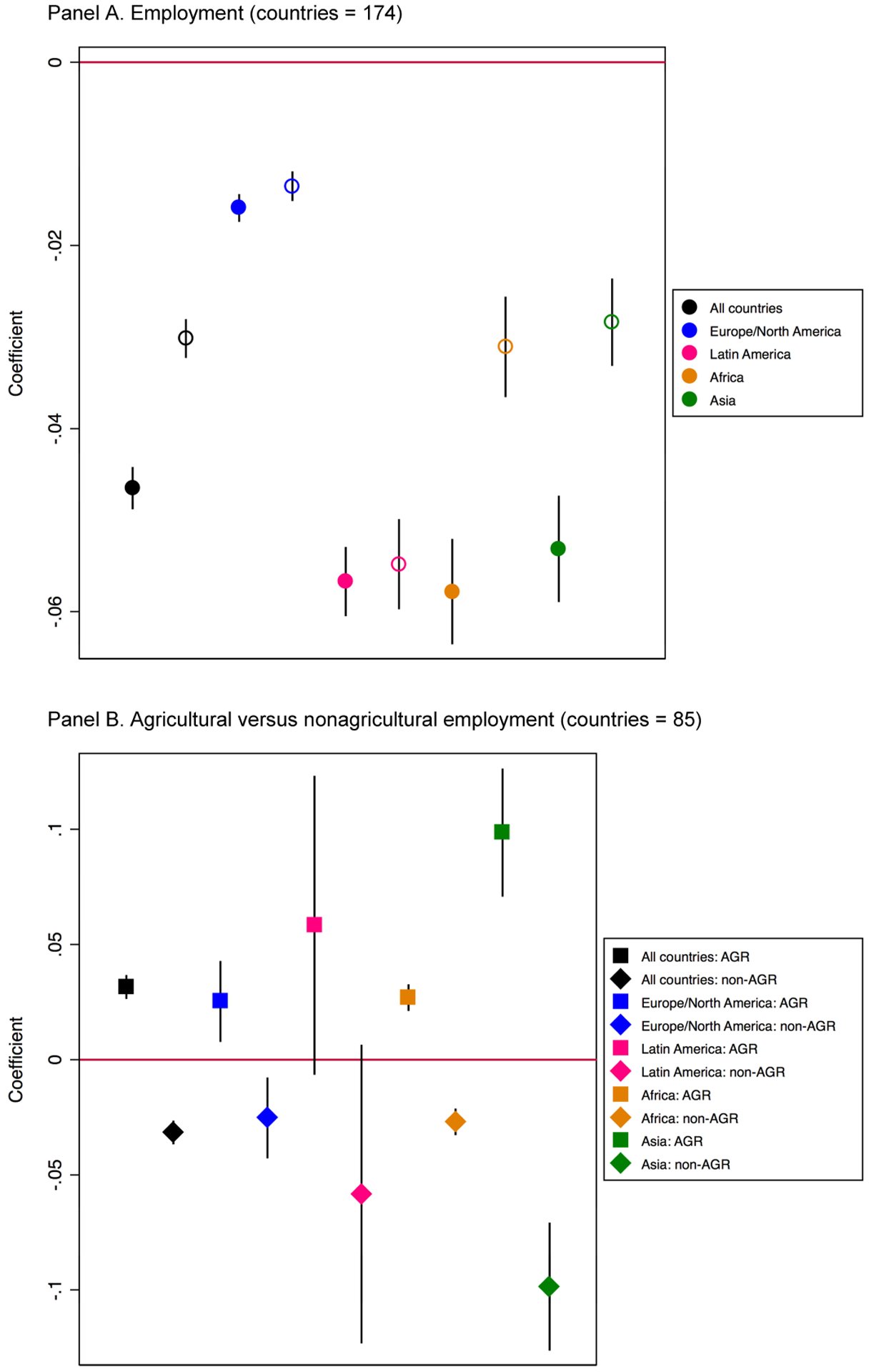

4.3. Linear associations between women’s employment, contraceptive use, and unmet need for family planning

Our next set of models uses the same empirical strategies to explore linear associations between women’s employment and fertility regulation via contraceptive use. As Figure 3, Panel A, shows, there is a significant positive association between women’s employment and modern contraceptive use in both the pooled sample and in all four regional analyses (this is true with and without controls). Nonetheless there is important regional heterogeneity in the magnitude of the coefficients: The association between women’s employment and modern contraceptive use is significantly higher in Latin America (pink dot) and lower in Africa and Asia (orange and green dots), net of controls for GDP and GPI. Similar to what we documented with TFR, the relationship of interest varies by type of employment. Figure 3, Panel B, shows that women’s agricultural employment is negatively associated with modern contraceptive use (black square) and that women’s nonagricultural employment is positively associated with modern contraceptive use (black diamond) in the pooled model. This general pattern holds in the region-specific analyses as well, although some of the coefficients fail to reach statistical significance at p < 0.05, likely due to reduced sample size, which falls from 168 countries to 85 in the pooled analysis due to lack of data on type of employment.

Figure 3:

Linear association between wage employment and modern contraceptive use with country fixed effects (1960–2015). Panel A shows the empty model (solid dots) and the model with controls for GDP and GPI (hollow dots). Panel B disaggregates by agricultural versus nonagricultural employment.

Source: Created by the authors using data from ILO, United Nations, and World Bank.

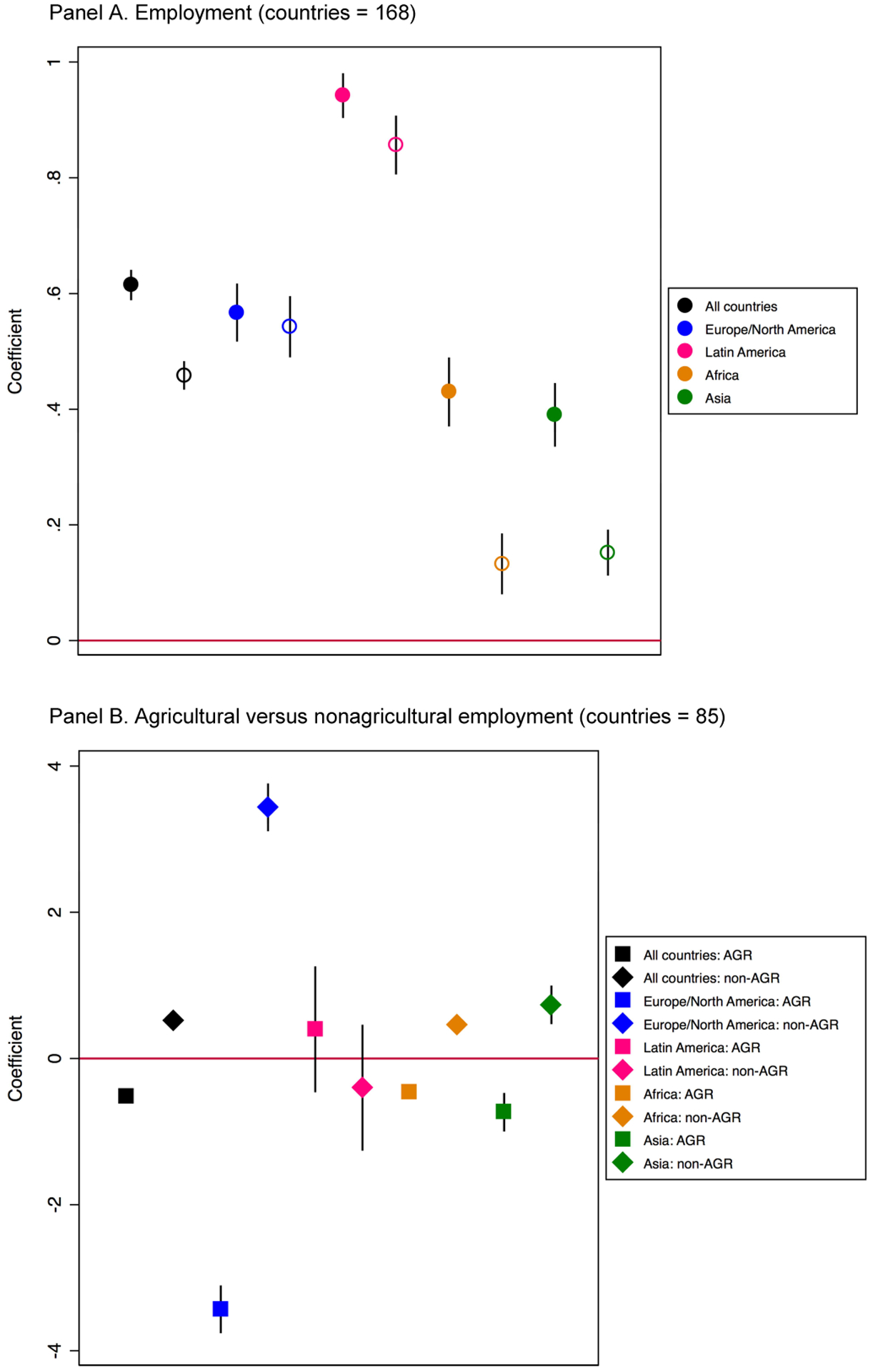

Figure 4, Panel A, presents results of the linear association between women’s wage employment and unmet need for family planning, documenting a significant negative association between women’s employment and unmet need for family planning in both the pooled sample and all four regions (although the Africa and Asia coefficients fail to achieve significance at p < 0.05 upon including controls for GDP and GPI). Also of note is that the magnitude of the employment–unmet need correlation is significantly larger in Latin American (pink dot) and Europe/North America (blue dot) than in the other regions. Once we disaggregate by type of employment in Figure 4, Panel B, we see that agricultural employment is positively associated with unmet need for family planning and that nonagricultural employment is negatively associated with unmet need for family planning in the pooled analysis, a pattern that holds in the region-specific analyses as well, although some of the coefficients fail to reach statistical significance at p < 0.05, likely due to reduced sample size in this sub-analysis.

Figure 4:

Linear association between wage employment and unmet need for modern methods of family planning with country fixed effects (1960–2015). Panel A shows the empty model (solid dots) and the model with controls for GDP and GPI (hollow dots). Panel B disaggregates by agricultural versus nonagricultural employment.

Source: Created by the authors using data from ILO, United Nations, and World Bank.

5. Discussion

This paper expands the scope of the literature on women’s employment and fertility to a truly global scale by compiling a unique dataset on women’s wage employment and reproductive outcomes in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Our analyses document a significant negative linear association between women’s wage employment and the total fertility rate at the country level in every major world region. Furthermore, there is a negative association between women’s employment and unmet need for family planning and a positive association between women’s country-level employment and modern contraception use in all regions. Nonetheless, our results suggest important variation depending on the type of employment. Generally speaking, there is a negative correlation between nonagricultural employment and TFR and unmet need for family planning, and a positive correlation between nonagricultural employment and contraceptive use. On the other hand, there is a positive correlation between agricultural employment and TFR and unmet need for family planning, and a negative correlation between agricultural employment and contraceptive use.

While our main findings are similar cross-regionally, there are a number of important regional differences in the magnitude of these associations. On one hand, the negative associations between women’s employment and TFR and unmet need for family planning are significantly larger for Latin America than any other region, as is the positive association between women’s employment and modern contraceptive use. In part, this could be related to the fact that Latin American countries in our study underwent both a large fertility transition and a dramatic increase in women’s employment during the period of our study. On the other hand, most of the countries in Europe/North America had already undergone the fertility transition by the time period covered in our study, and many already had work–family reconciliation policies that helped ease potential incompatibilities. At the other extreme, many countries in Asia and Africa did not undergo such dramatic transformations, and the fact that a high share of women’s employment continues to be concentrated in agriculture in these regions could help explain why magnitudes of the correlation between employment and fertility/reproductive health outcomes are significantly smaller than in other regions.

Although our study provides an important global overview of employment and fertility, it has a number of limitations. First, our use of aggregate data prevents us from making individual-level inferences about associations between women’s employment and fertility. However, the use of aggregate data also has advantages: the experience of living in a country where many women are employed may have important spillover effects even among unemployed women; these could be captured by our analyses. A second limitation of our analysis is that we cannot address the directionality of the employment and fertility correlation, and in particular whether employment leads to higher fertility or fertility leads to more employment. It is possible (and likely) that both could be true. (The same goes for correlations between employment and modern contraceptive use/unmet need for family planning.) A third limitation of our analysis is that our measure of fertility (TFR) is age standardized but our other measures (such as employment) are not, which implies that changes in a country’s age structure could have some bearing on the empirical associations presented here.

Finally, it is important to note that our results represent associations only; there may be unobserved time-varying factors at the country level that help explain the correlations between employment and fertility/contraceptive use reported in our paper. For example, population age structures could change in ways that are favorable for economic growth and changes in living standards, both of which often correlate with employment and fertility (although since age structure is partly endogenous to TFR, it might be complicated to look at a correlation between employment and TFR net of age structure). At the same time, there could be government or policy changes related to reproduction, contraceptive dissemination, or women’s economic empowerment, all of which would be relevant for the variables of interest in our study. Likewise, over time, patterns of both internal and external migration could change, which would be relevant, since migration is often correlated with both employment and fertility outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, this paper represents the most complete global exploration of the employment and fertility correlation to date, covering a wide range of countries and data sources. We have widened the employment–fertility debate to include a greater range of reproductive health outcomes as opposed to the narrower focus on fertility that is common in the literature. Our analysis also enhances conversations about the mechanisms through which employment is associated with fertility change by bringing together literature from low- and high-income countries. The dominant approach in the sociological literature on high-income countries attributes the negative correlation between women’s employment and fertility to the logistical incompatibilities women face in combining child care and employment outside the home (Brinton and Lee 2016; McDonald 2000a, 2000b). On the other hand, in low-income countries, wage employment is often conceptualized as empowering by improving women’s ability to bargain over fertility and family decisions (Anderson and Eswaran 2009; Duflo 2012; Narayan-Parker 2005). Bringing these literatures into conversation with each other raises the important possibility that empowerment may help explain some of what we see in high-income countries and that incompatibility may explain some of what we see in low-income countries. Taken together, these approaches provide a more complete and nuanced understanding of the mechanisms between employment and fertility in a truly global context.

6. Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hans-Peter Kohler, Sarah Hayford, Ann Orloff, Mónica Caudillo, Abigail Weitzman, and the participants at the 2019 Gender, Power, Theory Workshop, the 2019 Global Family Change workshop, and the 2019 American Sociological Association Annual Meeting for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge support for this paper through the Global Family Change (GFC) project (http://web.sas.upenn.edu/gfc), which is a collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania, University of Oxford (Nuffield College), Bocconi University, and the Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics (CED) at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Appendix

Table A-1:

List of countries by region and number of observations

| 1: Europe/North America, NZ, Australia | 2: Latin America | 3: Africa | 4: Asia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO3 | Country | # | ISO3 | Country | # | ISO3 | Country | # | ISO3 | Country | # |

| 8: ALB | Albania | 12 | 28: ATG | Antigua and Barbuda | 30 | 12: DZA | Algeria | 40 | 4: AFG | Afghanistan | 36 |

| 36: AUS | Australia | 55 | 32: ARG | Argentina | 56 | 24: AGO | Angola | 29 | 31: AZE | Azerbaijan | 17 |

| 40: AUT | Austria | 55 | 44: BHS | Bahamas | 25 | 72: BWA | Botswana | 21 | 48: BHR | Bahrain | 38 |

| 56: BEL | Belgium | 55 | 52: BRB | Barbados | 43 | 108: BDI | Burundi | 36 | 50: BGD | Bangladesh | 42 |

| 70: BIH | Bornia | 9 | 68: BOL | Bolivia | 40 | 120: CMR | Cameroon | 39 | 51: ARM | Armenia | 19 |

| 100: BGR | Bulgaria | 51 | 76: BRA | Brazil | 50 | 132: CPV | Cabo Verde | 34 | 64: BTN | Bhutan | 8 |

| 112: BLR | Belarus | 26 | 84: BLZ | Belize | 21 | 148: TCD | Chad | 14 | 96: BRN | Brunei | 46 |

| 124: CAN | Canada | 53 | 152: CHL | Chile | 55 | 174: COM | Comoros | 25 | 104: MMR | Myanmar | 32 |

| 191: HRV | Croatia | 25 | 170: COL | Colombia | 51 | 178: COG | Congo | 27 | 116: KHM | Cambodia | 52 |

| 203: CZE | Czechia | 25 | 188: CRI | Costa Rica | 43 | 180: COD | Dem Rep Congo | 8 | 144:LKA | Sri Lanka | 48 |

| 208: DNK | Denmark | 56 | 192: CUB | Cuba | 41 | 204: BEN | Benin | 37 | 156: CHN | China | 29 |

| 233: EST | Estonia | 27 | 214: DOM | Dominican Republic | 56 | 231: ETH | Ethiopia | 20 | 158: TWN | Taiwan | 38 |

| 246: FIN | Finland | 56 | 218: ECU | Ecuador | 54 | 266: GAB | Gabon | 18 | 196: CYP | Cyprus | 40 |

| 250: FRA | France | 54 | 222: SLV | El Salvador | 53 | 270: GMB | Gambia | 29 | 242: FJI | Fiji | 43 |

| 276: DEU | Germany | 33 | 254: GUF | French Guiana | 30 | 288: GHA | Ghana | 52 | 258: PYF | French Polynesia | 29 |

| 300: GRC | Greece | 55 | 312: GLP | Guadeloupe | 32 | 324: GIN | Guinea | 20 | 268: GEO | Georgia | 17 |

| 348: HUN | Hungary | 56 | 320: GTM | Guatemala | 50 | 384: CIV | Cote d’Ivoire | 33 | 275: PSE | Palestine | 15 |

| 352: ISL | Iceland | 56 | 328: GUY | Guyana | 34 | 404: KEN | Kenya | 7 | 296: KIR | Kiribati | 33 |

| 372: IRL | Ireland | 50 | 332: HTI | Haiti | 35 | 426: LSO | Lesotho | 15 | 316: GUM | Guam | 21 |

| 380: ITA | Italy | 55 | 340: HND | Honduras | 40 | 430: LBR | Liberia | 50 | 344: HKG | Hong Kong | 50 |

| 428: LVA | Latvia | 27 | 388: JAM | Jamaica | 22 | 434: LBY | Libya | 2 | 356: IND | India | 32 |

| 440: LTU | Lithuania | 27 | 474: MTQ | Martinique | 48 | 450: MDG | Madagascar | 40 | 360:IDN | Indonesia | 44 |

| 442: LUX | Luxembourg | 56 | 484: MEX | Mexico | 45 | 454: MWI | Malawi | 32 | 364:IRN | Iran | 40 |

| 470: MLT | Malta | 31 | 533: ABW | Aruba | 21 | 466: MLI | Mali | 39 | 368: IRQ | Iraq | 34 |

| 498: MDA | Moldova | 26 | 558: NIC | Nicaragua | 39 | 478: MRT | Mauritania | 13 | 376: ISR | Israel | 33 |

| 499: MNE | Montenegro | 5 | 591: PAN | Panama | 56 | 480: MUS | Mauritius | 33 | 392: JPN | Japan | 56 |

| 528: NLD | Netherlands | 56 | 600: PRY | Paraguay | 37 | 504: MAR | Morocco | 52 | 398: KAZ | Kazakhstan | 14 |

| 554: NZL | New Zealand | 30 | 604: PER | Peru | 55 | 508: MOZ | Mozambique | 44 | 400: JOR | Jordan | 54 |

| 578: NOR | Norway | 55 | 630: PRI | Puerto Rico | 56 | 516: NAM | Namibia | 22 | 410: KOR | South Korea | 56 |

| 616: POL | Poland | 56 | 662: LCA | Saint Lucia | 13 | 562: NER | Niger | 38 | 414: KWT | Kuwait | 51 |

| 620: PRT | Portugal | 56 | 740: SUR | Suriname | 50 | 566: NGA | Nigeria | 48 | 417: KGZ | Kyrgyzstan | 27 |

| 642: ROU | Romania | 50 | 780: TTO | Trinidad and Tobago | 43 | 638: REU | Reunion | 52 | 418: LAO | Laos | 21 |

| 643: RUS | Russia | 27 | 858: URY | Uruguay | 32 | 646: RWA | Rwanda | 37 | 422: LBN | Lebanon | 4 |

| 688: SRB | Serbia | 10 | 862: VEN | Venezuela | 52 | 678: STP | Sao Tome | 11 | 446: MAC | Macao | 56 |

| 703: SVK | Slovakia | 25 | 686: SEN | Senegal | 26 | 458: MYS | Malaysia | 36 | |||

| 705: SVN | Slovenia | 25 | 690: SYC | Seychelles | 45 | 462: MDV | Maldives | 38 | |||

| 724: ESP | Spain | 46 | 694: SLE | Sierra Leone | 12 | 496: MNG | Mongolia | 13 | |||

| 752: SWE | Sweden | 51 | 710: ZAF | South Africa | 54 | 512: OMN | Oman | 16 | |||

| 756: CHE | Switzerland | 56 | 716: ZWE | Zimbabwe | 33 | 524: NPL | Nepal | 35 | |||

| 804: UKR | Ukraine | 36 | 729: SDN | Sudan | 39 | 548: VUT | Vanuatu | 31 | |||

| 807: MKD | Macedonia | 23 | 748: SWZ | Eswatini | 48 | 586: PAK | Pakistan | 40 | |||

| 826: GBR | United Kingdom | 43 | 768: TGO | Togo | 32 | 598: PNG | Papua New Guinea | 34 | |||

| 840: USA | United States | 56 | 788: TUN | Tunisia | 48 | 608: PHL | Philippines | 53 | |||

| 800: UGA | Uganda | 22 | 626: TLS | Timor-Leste | 10 | ||||||

| 818: EGY | Egypt | 55 | 634: QAT | Qatar | 30 | ||||||

| 834: TZA | Tanzania | 37 | 682: SAU | Saudi Arabia | 24 | ||||||

| 854: BFA | Burkina Faso | 30 | 702: SGP | Singapore | 46 | ||||||

| 894: ZMB | Zambia | 33 | 704: VNM | Viet Nam | 26 | ||||||

| 760: SYR | Syria | 45 | |||||||||

| 762: TJK | Tajikistan | 6 | |||||||||

| 764: THA | Thailand | 40 | |||||||||

| 776: TON | Tonga | 29 | |||||||||

| 784: ARE | Arab Emirates | 35 | |||||||||

| 792: TUR | Turkey | 44 | |||||||||

| 882: WSM | Samoa | 52 | |||||||||

| 887: YEM | Yemen | 19 | |||||||||

Note: The number of observations is the number of years for which both women’s employment and fertility measures are available.

Table A-2:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between wage employment and TFR, 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Women’s employment rate | −0.0465*** | −0.0302*** | −0.0159*** | −0.0135*** | −0.0567*** | −0.0548*** | −0.0578*** | −0.0311*** | −0.0531*** | −0.0284*** |

| (0.00119) | (0.00108) | (0.000772) | (0.000824) | (0.00193) | (0.00251) | (0.00293) | (0.00280) | (0.00297) | (0.00243) | |

| GDP | −0.000145*** | 7.34e-05 | 0.000450* | −0.00449 | −0.000150*** | |||||

| (3.78e-05) | (0.000283) | (0.000243) | (0.00361) | (4.43e-05) | ||||||

| Gender inequality in secondary education access | −6.458*** | −2.431*** | −2.209*** | −5.701*** | −7.609*** | |||||

| (0.150) | (0.293) | (0.781) | (0.267) | (0.250) | ||||||

| Constant | 5.902*** | 11.09*** | 2.691*** | 4.970*** | 5.745*** | 7.804*** | 8.624*** | 11.95*** | 5.926*** | 11.88*** |

| (0.0638) | (0.132) | (0.0497) | (0.280) | (0.0910) | (0.731) | (0.164) | (0.216) | (0.139) | (0.223) | |

| Country fixed effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 5,062 | 5,062 | 1,341 | 1,341 | 1,007 | 1,007 | 1,296 | 1,296 | 1,418 | 1,418 |

| R-squared | 0.239 | 0.448 | 0.247 | 0.285 | 0.471 | 0.479 | 0.238 | 0.445 | 0.190 | 0.518 |

| Number of countries | 174 | 174 | 42 | 42 | 32 | 32 | 48 | 48 | 52 | 9 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Table A-3:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between women’s employment and modern contraceptive use, 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Women’s employment rate | 0.615*** | 0.459*** | 0.567*** | 0.543*** | 0.942*** | 0.857*** | 0.430*** | 0.132*** | 0.390*** | 0.152*** |

| (0.0134) | (0.0125) | (0.0255) | (0.0270) | (0.0197) | (0.0258) | (0.0304) | (0.0268) | (0.0281) | (0.0203) | |

| GDP | 0.00371*** | 0.0256 | 0.0118*** |

0.191*** | 0.00272*** | |||||

| (0.000433) | (0.0284) | (0.00204) | (0.0355) | (0.000359) | ||||||

| Gender inequality in secondary education access | 61.24*** | 25.67*** | 19.70** | 66.44*** | 74.11*** | |||||

| (1.690) | (9.711) | (8.056) | (2.614) | (1.941) | ||||||

| Constant | 6.519*** | −42.95*** | 18.53*** | −5.914 | 4.086*** | −13.74* | −4.734*** | −47.61*** | 18.73*** | −40.01*** |

| (0.715) | (1.501) | (1.646) | (9.349) | (0.940) | (7.538) | (1.688) | (2.125) | (1.284) | (1.763) | |

| Country fixed effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 5,032 | 5,032 | 1,300 | 1,300 | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,300 | 1,300 | 1,392 | 1,392 |

| R-squared | 0.303 | 0.456 | 0.282 | 0.286 | 0.694 | 0.704 | 0.138 | 0.450 | 0.126 | 0.587 |

| Number of countries | 168 | 168 | 40 | 40 | 31 | 31 | 47 | 47 | 50 | 50 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Table A-4:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between women’s employment and unmet need for modern family planning, 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Women’s employment rate | −0.305*** | −0.263*** | −0.531*** | −0.503*** | −0.451*** | −0.430*** | −0.125*** | −0.0187 | −0.0851*** | −0.0159 |

| (0.00820) | (0.00851) | (0.0241) | (0.0255) | (0.0109) | (0.0142) | (0.0144) | (0.0141) | (0.0114) | (0.0102) | |

| GDP | −0.00186*** | −0.0529** | −0.00653*** | −0.106*** | −0.00143*** | |||||

| (0.000293) | (0.0268) | (0.00113) | (0.0186) | (0.000180) | ||||||

| Gender inequality in secondary education access | −15.86*** | −27.32*** | 5.903 | −23.44*** | −21.16*** | |||||

| (1.147) | (9.161) | (4.437) | (1.371) | (0.973) | ||||||

| Constant | 44.06*** | 56.92*** | 58.74*** | 84.94*** | 46.71*** | 40.94*** | 38.52*** | 54.53*** | 33.03*** | 50.01*** |

| (0.439) | (1.018) | (1.555) | (8.820) | (0.519) | (4.151) | (0.799) | (1.114) | (0.522) | (0.884) | |

| Country fixed effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 5,032 | 5,032 | 1,300 | 1,300 | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,300 | 1,300 | 1,392 | 1,392 |

| R-squared | 0.221 | 0.256 | 0.279 | 0.285 | 0.630 | 0.644 | 0.057 | 0.263 | 0.040 | 0.309 |

| Number of countries | 168 | 168 | 40 | 40 | 31 | 31 | 47 | 47 | 50 | 50 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Table A-5:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between women’s employment and TFR by employment type (agricultural versus nonagricultural), 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | |

| Women’s employment rate | 0.0316*** | −0.0316*** | 0.0253*** | −0.0253*** | 0.0584* | −0.0584* | 0.0270*** | −0.0270*** | 0.0986*** | −0.0986*** |

| (0.00264) | (0.00264) | (0.00893) | (0.00893) | (0.0329) | (0.0329) | (0.00291) | (0.00291) | (0.0141) | (0.0141) | |

| Constant | 2.080*** | 5.237*** | 1.678*** | 4.207*** | 2.268*** | 8.104** | 2.736*** | 5.432*** | 1.792*** | 11.65*** |

| (0.0135) | (0.253) | (0.0140) | (0.880) | (0.0888) | (3.207) | (0.0376) | (0.264) | (0.108) | (1.303) | |

| Country fixed-effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 1,044 | 1,044 | 462 | 462 | 242 | 242 | 140 | 140 | 200 | 200 |

| R-squared | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.409 | 0.409 | 0.219 | 0.219 |

| Number of countries | 85 | 85 | 28 | 28 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 24 | 24 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Table A-6:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between women’s employment and modern contraceptive use by employment type (agricultural versus nonagricultural), 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | |

| Women’s employment rate | −0.514*** | 0.514*** | −3.434*** | 3.434*** | 0.399 | −0.399 | −0.459*** | 0.459*** | −0.734*** | 0.734*** |

| (0.0364) | (0.0364) | (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.437) | (0.437) | (0.0369) | (0.0369) | (0.134) | (0.134) | |

| Constant | 58.05*** | 6.659* | 66.37*** | −277.1*** | 58.55*** | 98.44** | 49.50*** | 3.600 | 53.62*** | −19.83 |

| (0.190) | (3.492) | (0.267) | (16.39) | (1.197) | (42.56) | (0.462) | (3.348) | (1.049) | (12.34) | |

| Country fixed-effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 1,081 | 1,081 | 456 | 456 | 255 | 255 | 149 | 149 | 221 | 221 |

| R-squared | 0.167 | 0.167 | 0.498 | 0.498 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.542 | 0.542 | 0.133 | 0.133 |

| Number of countries | 85 | 85 | 26 | 26 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 23 | 23 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Table A-7:

Multivariate regression analysis of the association between women’s employment and unmet need for modern family planning by employment type (agricultural versus nonagricultural), 1960–2015, including country fixed effects

| Pooled | Pooled | Region 1 | Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | All countries | Europe/North America | Europe/North America | Latin America | Latin America | Africa | Africa | Asia | Asia | |

| Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | Agr | non-Agr | |

| Women’s employment rate | 0.265*** | −0.265*** | 3.127*** | −3.127*** | −0.292 | 0.292 | 0.205*** | −0.205*** | 0.498*** | −0.498*** |

| (0.0267) | (0.0267) | (0.161) | (0.161) | (0.291) | (0.291) | (0.0225) | (0.0225) | (0.0799) | (0.0799) | |

| Constant | 20.69*** | 47.24*** | 14.33*** | 327.0*** | 21.34*** | −7.819 | 23.59*** | 44.13*** | 22.64*** | 72.41*** |

| (0.139) | (2.562) | (0.259) | (15.88) | (0.798) | (28.38) | (0.282) | (2.044) | (0.627) | (7.380) | |

| Country fixed-effects | ||||||||||

| Observations | 1,081 | 1,081 | 456 | 456 | 255 | 255 | 149 | 149 | 221 | 221 |

| R-squared | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.467 | 0.467 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.389 | 0.389 | 0.165 | 0.165 |

| Number of countries | 85 | 85 | 26 | 26 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 23 | 23 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1

Footnotes

In the last two decades, the labor force participation of both women and men has decreased (ILO 2016).

Informal employment is characterized by jobs that are not covered by labor law or social protection and are often poorly compensated (ILO 2015).

We use linear interpolation to fill gaps between observed years of data, and we do not extrapolate outside the range of years included in the data. For instance, if we had data for France between 1975 and 2010 in five-year intervals, the linear interpolation method would only impute values between those five-year intervals, resulting in a yearly series from 1975 to 2010. Thus this method imputes values to complete the time series between the first and the last year of observed data, but it does not generate single-year data between 1960 and 2015 for all countries. This linear interpolation method on average adds only one year of data in the analysis of the association between employment and TFR and about 1.3 years of data in analysis of the association between employment type and TFR. Linear interpolation does not add additional years of data on analyses that look at contraceptive use or unmet need for contraception because these data are already imputed in the original source.

In some instances, different methods are used to calculate TFR. To ensure consistency, we select one method per country, preferring the direct method when available. Results (available upon request) are robust due to including only countries that use the direct method.

Formally, unmet need for family planning is calculated by summing (a) the number of women of reproductive age (married or in unions) who are not using contraception, are fecund, and desire to either stop childbearing or to postpone their next birth for at least two years; (b) pregnant women whose current pregnancies were unwanted or mistimed; and (c) women in postpartum amenorrhea who are not using contraception and, at the time they became pregnant, had wanted to delay or prevent the pregnancy. This total is divided by the number of women of reproductive age (15–49) who are married or in a union. The result is multiplied by 100.

While employment is on the right-hand side in the linear associations in our paper, results are substantively the same if fertility is instead on the right-hand side.

References

- Aguero J and Marks MS (2008). Motherhood and female labor force participation: Evidence from infertility shocks. The American Economic Review 98(2): 500–504. doi: 10.1257/aer. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn N and Mira P (2002). A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. Journal of Population Economics 15(4): 667–682. doi: 10.1007/s001480100078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf K (2007). Couples’ reports of women’s autonomy and health-care use in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning 38(1): 35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Samarrai S and Bennell P (2007). Where has all the education gone in sub-Saharan Africa? Employment and other outcomes among secondary school and university leavers. Journal of Development Studies 43(7): 1270–1300. doi: 10.1080/00220380701526592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S and Eswaran M (2009). What determines female autonomy? Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Development Economics 90(2): 179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD and Evans WN (1998). Children and their parents’ labor supply: Evidence from exogenous variation in family size. The American Economic Review 88(3): 450–477. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M (2006). More power to the pill: The impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s life cycle labor supply. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(1): 289–320. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2006.121.1.289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JS, Kusunoki Y, Gatny HH, and Budnick J (2018). The dynamics of intimate partner violence and the risk of pregnancy during the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review 83(5): 1020–1047. doi: 10.1177/0003122418795856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS and Lewis HG (1974). Interaction between quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy 81(2): S279–S288. doi: 10.1086/260166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beegle K, Frankenberg E, and Thomas D (2001). Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia. Studies in Family Planning 32(2): 130–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JA (2017). Women’s land ownership and participation in decision-making about reproductive health in Malawi. Population and Environment 38(4): 327–344. doi: 10.1007/s11111-017-0272-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt EM (1993). Fertility and employment. European Sociological Review 9(1): 25–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone A and Stewart MD (2012). Choosing to be childfree: Research on the decision not to parent. Sociology Compass 6(9): 718–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2012.00496.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Canning D, Fink G, and Finlay JE (2009). Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. Journal of Economic Growth 14(2): 79–101. doi: 10.1007/s10887-009-9039-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, Blanc AK, and McCarthy KJ (2019). The links between women’s employment and children at home: Variations in low- and middle-income countries by world region. Population Studies 73(2): 149–163. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2019.1581896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourmpoula E, Kapsos S, and Pasteels J-M (2016). ILO labor force estimates and projections: 1990–2050 methodological description. Geneva: International Labour Organization; (2015 edition). [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL and Rindfuss RR (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology 26(1): 271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton MC and Lee D-J (2016). Gender-role ideology, labor market institutions, and post-industrial fertility. Population and Development Review 42(3): 405–433. doi: 10.1111/padr.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres-Delpiano J (2012). Can we still learn something from the relationship between fertility and mother’s employment? Evidence from developing countries. Demography 49(1): 151–174. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnais J (1996). Fertility, family, and social policy in contemporary Western Europe. Population and Development Review 22(4): 729–739. doi: 10.2307/2137807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Kabiru CW, Laszlo S, and Muthuri S (2019). The impact of childcare on poor urban women’s economic empowerment in Africa. Demography 56(4): 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s13524-019-00793-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruces G and Galiani S (2007). Fertility and female labor supply in Latin America: New causal evidence. Labour Economics 14(3): 565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2005.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva T and Tenreyro S (Forthcoming). The fall in global fertility: A quantitative model. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmalingam A and Morgan P (2004). Pervasive Muslim-Hindu fertility differences in India. Demography 41(3): 529–545. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorius SF (2008). Global demographic convergence? A reconsideration of changing intercountry inequality in fertility. Population and Development Review 34(3): 519–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doss C (2005). The effects of intrahousehold property ownership on expenditure patterns in Ghana. Journal of African Economies 15(1): 149–180. doi: 10.1093/jae/eji025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duflo E (2012). Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50(4): 1051–1079. doi: 10.1257/jel.50.4.1051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G and Billari FC (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review 41(1): 1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00024.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber M, Green CA, and Spaeth JL (1986). Work power and earnings of women and men. The American Economic Review 76(2): 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay JE (2019). Fertility and women’s work in the context of women’s economic empowerment: Inequalities across regions and wealth quintiles. Paper presented at Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Austin TX, April 10–13 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C (1995). Career and family: College women look to the past. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. (NBER Working Paper 5188). doi: 10.3386/w5188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C (2006). The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. (NBER Working Paper 11953). doi: 10.3386/w11953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C and Katz LF (2002). The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. Journal of Political Economy 110(4): 730–770. doi: 10.1086/340778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Bernhardt E, and Lappegård T (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review 41(2): 207–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hino H and Ranis G (eds.). (2014). Youth and employment in sub-Saharan Africa. Abingdon, Oxon and New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203798935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J (1990). Social policy and recent fertility change in Sweden. Population and Development Review 16(4): 735–748. doi: 10.2307/1972965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2015). Export-led development, employment and gender in the era of globalization. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO Report 197). [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2016). Women at Work: Trends 2016. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2018a). World employment and social outlook – Trends for women 2018 – Global snapshot. Geneva: International Labour Organization. doi: 10.1002/wow3.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2018b). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2019). Employment-to-population ratio. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30(3): 435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantorova V (2019). Contraceptive prevalence. New York: United Nations Population Division. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Billari FC, and Ortega JA (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review 28(4): 641–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00641.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P (2000a). Gender equity, social institutions and the future of fertility. Journal of Population Research 17(1): 1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03029445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P (2000b). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review 26(3): 427–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00427.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P (2006). Low fertility and the state: The efficacy of policy. Population and Development Review 32(3): 485–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00134.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P (1991). Transitions in mid-life: Women’s work and family roles in the 1970s. Journal of Marriage and Family 53(1): 135–150. doi: 10.2307/353139?refreqid=search-gateway:c65b4bb1ee72a1248a5497805bbbdc98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP (2003). Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography 40(4): 589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan-Parker D (ed.). (2005). Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. doi: 10.1037/e597202012-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pesando LM and GFC Team (2019). Global family change: Persistent diversity with development. Population and Development Review 45(1): 133–168. doi: 10.1111/padr.12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing A and Maluccio JA (2003). Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 65(3): 283–327. doi: 10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR and Brewster KL (1996). Childrearing and fertility Population and Development Review 22(Supplement: Fertility in the United States: new patterns, new theories): 258–289. doi: 10.2307/2808014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig MR and Wolpin KI (1980). Testing the quantity-quality fertility model: The use of twins as a natural experiment. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 48(1): 227–240. doi: 10.2307/1912026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S (2015). Patriarchy, power, and pay: The transformation of American families, 1800–2015. Demography 52(6): 1797–1823. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0440-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, and Riley AP (1997). The influence of women’s changing roles and status in Bangladesh’s fertility transition: Evidence from a study of credit programs and contraceptive use. World Development 25(4): 563–575. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00119-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spain D and Bianchi SM (1997). Balancing act: Motherhood, marriage, and employment among American women. New York: Russel Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Stycos JM and Weller RH (1967). Female working roles and fertility. Demography 4(1): 210–217. doi: 10.2307/2060362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay UD, Gipson JD, Withers M, Lewis S, Ciaraldi EJ, Fraser A, Huchko MJ, and Prata N (2014). Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine 115(C): 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay UD and Hindin MJ (2005). Do higher status and more autonomous women have longer birth intervals? Social Science and Medicine 60(11): 2641–2655. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ (1980). Working wives and the family life cycle. American Journal of Sociology 86(2): 272–294. doi: 10.2307/2778665?refreqid=search-gateway:295b6f4b3c2aae78e6d456d2d50053d4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller RH (1977). Wife’s employment and cumulative family size in The United States, 1970 and 1960. Demography 14(1): 43–65. doi: 10.2307/2060454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]