Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of embolic diameter on the achievement of hypoxia following embolization in a preclinical model of liver tumors.

Materials and Methods

Inoculation of Vx2 tumors in the left liver lobe was performed successfully in 12 new Zealand white rabbits weighing 3.7 kg ± 0.5kg (mean + SD). Tumors were deemed eligible for oxygen measurements when the maximum transverse diameter measured 15mm or more by ultrasound examination. Direct monitoring of oxygenation of implanted rabbit hepatic Vx2 tumors was performed with a fiberoptic electrode during and following transarterial embolization of the proper hepatic artery to angiographic flow stasis with microspheres measuring 70–150, 100–300, or 300–500 microns in diameter.

Results

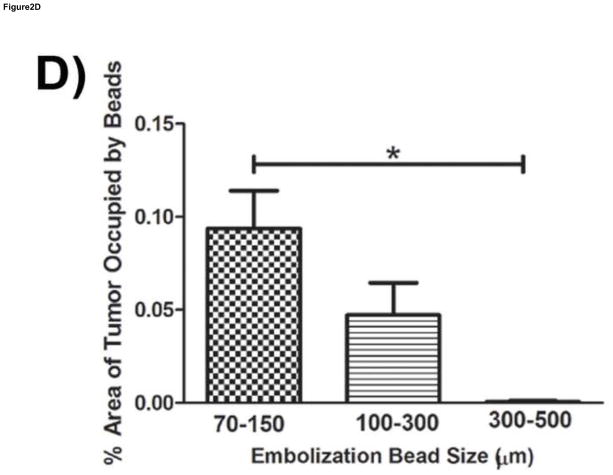

Failure to achieve tumor hypoxia as defined despite angiographic flow stasis was observed in ten of eleven total animals. Embolization microsphere size effect failed to demonstrate a significant trend on hypoxia outcome among the diameters tested, and pair-wise comparisons of different embolic diameter treatment groups showed no difference in hypoxia outcome. All microsphere diameters tested resulted in similar absolute reduction (24.3 ± 18.3, 29.1 ± 1.8, and 19.9 ± 9.3 mm Hg, p=0.66) and percentage drop in oxygen (56.0 ± 23.9, 56.0 ±6.4, and 35.8 ± 20.6 mm Hg, p=0.65) Pairwise comparisons for percent tumor area occupied by embolics showed a significantly reduced fraction for 300–500 μm compared to 70–150 μm diameters (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

In the rabbit Vx2 liver tumor model, three tested microsphere diameters failed to cause tumor hypoxia measured by a fiberoptic probe sensor according to the adopted hypoxia definitions, although an influence of embolic diameter upon achieved post-embolization hypoxia severity was determined.

Introduction

Tissue hypoxia is defined as inadequate local oxygen concentration to maintain life-sustaining cellular functions (1). Solid tumor tissue is often poorly oxygenated, due to abnormal, disorganized vasculature that does not deliver sufficient oxygen to meet cellular demand (2). Solid tumors may outgrow their blood supply, resulting primarily in diffusion-limited hypoxia. Transarterial embolization theoretically increases tumor hypoxia further by reducing tumor perfusion.

Transarterial embolization (TAE) or chemoembolization (TACE) are widely practiced therapeutic options for nonsurgical treatment of benign and malignant tumor control. However, reports describing the magnitude and distribution of the acute hypoxia occurring following arterial embolization are limited (3, 4). This knowledge is important because hypoxia may lead to apoptotic cell death or cause resistance to chemo- and radiation therapy (5).

Dreher et al provide a rationale to adopt smaller diameter embolics for TAE and drug eluting embolic TACE (DEB-TACE) including 1) to permit more distal drug delivery, and 2) greater and potentially more uniform drug coverage (6). It is widely believed that a greater local ischemic effect is obtained by occluding smaller diameter distal arteries and preventing the development of collaterals, (7, 8).

The data from this study in a pre-clinical liver tumor model provides an estimate of the relationship between embolization embolic diameter and severity of embolization-related tumor oxygenation changes.

Materials and methods

Animal care and experimental design were approved by an NIH Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Vx2 tumors were propagated as described by Lee et al and Geschwind et al. and modified by Ranjan et al. (9–11). Briefly, Vx2 was propagated in a donor rabbit and inoculated into subsequent donor (hindlimb) rabbits as a single cell suspension under ultrasound guidance. Vx2 intrahepatic tumors were established by percutaneous injection of tumor fragments into the left lobe of the liver of female New Zealand white rabbits weighing 3.7 ± 0.5kg under ultrasound guidance and monitored with ultrasound for 2–3 weeks until tumor diameter measuring 1.5cm or greater in diameter was confirmed. After induction of anesthesia with ketamine (20mg/kg; Vedco Inc., St. Joseph, MO), Acepromazine (0.75mg/kg IM; Vedco), Glycopyrolate (0.12mg IM; Baxter Healthcare, Dearfield, IL) and Ketofen (5mg; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA), animals were maintained under general anesthesia with isoflurane 0.5 to 1.5% and oxygen at 2L/min by mask. Catheterization of the proper hepatic artery was achieved via femoral artery cutdown and cannulation with a 3F vascular sheath (Cook, Bloomington, IN). The proper hepatic artery was selectively catheterized with a 2.4F microcatheter (Progreat™, Terumo, Somerset, NJ). Digital subtraction arteriography was then performed using a 9900 Elite Digital Mobile Super C-arm (GE Healthcare/OEC Medical Systems, Inc., Waukesha, WI) to confirm satisfactory catheter tip position for embolization in addition to determining the angiographic appearance of the tumor and presence of vasospasm.

Animals were randomly assigned to receive 300–500 μm, 100–300 μm or 70–150 μm LC Bead® (Biocompatibles UK Ltd, a BTG International group company, Farnham, UK), composed of acrylamido polyvinyl alcohol– co –acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonate hydrogel. Embolization particles were injected with the catheter tip in the proper hepatic artery. The beads were diluted to 1:20 by volume in saline/Isovue 300 contrast (1:1) mixture, and 0.5cc aliquots of the assigned bead mixture was delivered every five minutes followed by a saline flush until flow stasis was achieved. In the event that flow stasis was not achieved following the administration of 4cc of the bead suspension (a total of 0.2cc packed bead volume), a larger volume of bead suspension was injected (a maximum of 2cc bead suspension per aliquot) at the discretion of the operator. The angiographic embolization endpoint was complete flow stasis, defined as no contrast delivery visible in the left hepatic artery or its proximal branches. Animals were euthanized no less than five minutes following documentation of flow stasis and the tumor tissue harvested and flash frozen.

Oxygen measurements

The Oxylite™ fiber-optic oxygen sensor induces pulsatile fluorescence of a ruthenium lumiphor in the tip of the needle-like probe using a 525nm blue light-emitting diode. The duration or lifetime of the 650nm fluorescent pulse is inversely proportional to the oxygen tension at the probe tip. The probe measurement range is 0–200mm Hg, or 0–26.6kPa over a temperature range of 0–50° C. The measurement precision and accuracy reported by the manufacturer is ± 0.7mm Hg (0–7mm Hg), and ± 10% of oxygen value (7–150mm Hg). The feasibility of fluorescent probe tissue oxygen measurement has been previously established (12, 13). An Oxylite™ LAS 1 probe (Oxford Optronix, Oxford, UK) was percutaneously placed into the tumor targeting the tumor periphery under ultrasound guidance using a coaxial technique; a 21guage 1.25 inch Jelco catheter (Medex Medical Ltd., Rossendale, UK) was placed into the tumor, the introducer needle was removed, and the oxygen probe was then introduced in coaxial fashion. The Jelco catheter was withdrawn approximately 10mm to expose the measurement surface of the probe. Sonography following probe placement confirmed satisfactory probe position within the tumor. Continuous oxygen measurements were recorded in order to obtain an intratumor baseline oxygen level. An adequate baseline oxygen level was established only after observing a steep decline in oxygen content from 100 mmHg (atmospheric) to an equilibrium value which stabilized with less than 10% variance for at least five minutes after probe placement. Minimum baseline oxygen of greater than 20mmHg was required as even small variations in oxygen measurements below this level would exceed the 10% maximum allowed variation. Failure to achieve the minimal pO2 value required probe replacement. After achieving an adequate baseline, tumor oxygen pO2 was recorded continuously during embolization. Hypoxia was defined as a measured tumor pO2 of ≤5mm Hg. Results were tabulated as the number of tumors which achieved pO2 of ≤10mm Hg as well as pO2 ≤5mm Hg as the lowest oxygen level resulting in disruption of different cellular functions leading to cell death is disputed in the literature.

Histological evaluation

Frozen tissues were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and sliced into 5μm thick sections. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on serial sections from 2–5 equidistantly spaced regions throughout the tumor volume, depending upon tumor size. Whole section digital H&E histological scans were acquired with a 20× objective on a ScanScope CS (Aperio, Vista, CA) equipped with a color CCD camera. Image processing software (ImageScope, Aperio) was used to conduct microsphere count and area calculations. The microspheres were manually counted by a single staff scientist (C.G.) trained in identifying the beads in the tumor cross-sections (Figure 3). The ImageScope software allowed for zoomed viewing of the cross-sections and marking (green outline as shown in the figure) to ensure each bead was counted only once. An Excel spreadsheet was used to tally the information.

Data and statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism™ 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.) or StatXact™ v6.0 (Cytel Software Inc.). The Spearman correlation test was used to assess the trend observed between the microsphere diameter and achievement of hypoxia (pO2≤5mmHg) in animals embolized to stasis. For other parameters, groups were compared for homogeneity using ANOVA, followed by a Student-Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test (n=3–4). All p-values were two-sided and a p-value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Values are reported as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated.

Results

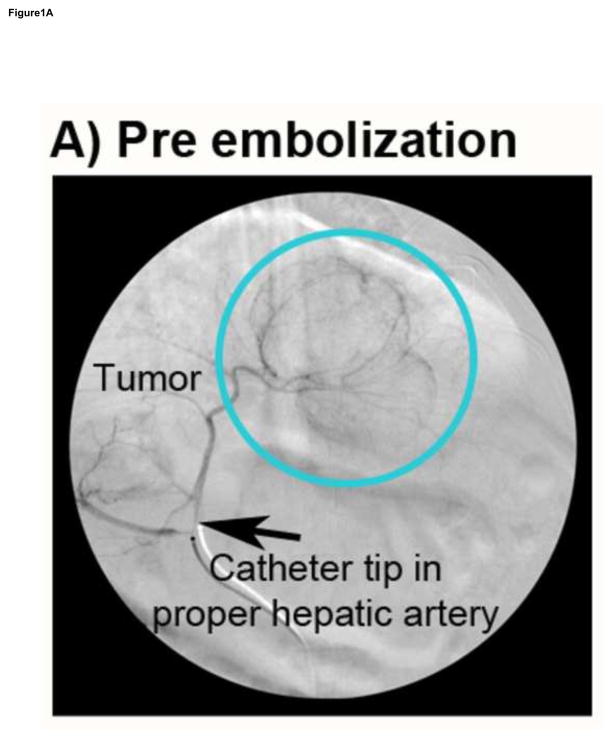

Eleven animals met all inclusion criteria for liver tumor size and oxygen measurements (n=3–4 per group). The overall mean Vx2 tumor size treated was 2.05 cm ± 0.4cm, and individual cohort means as determined sonographically (maximum dimension) were 2.47 ± 0.51 cm (70–150 μm), 2.00 ± 0.22 cm (100–300 μm), and 1.78 ± 0.21cm (300–500μm), with no statistical difference between groups (p=0.19). The distribution of hypovascular tumors was similar and there was no difference in baseline tumor oxygen level (Figure 1A) among the three embolization groups.

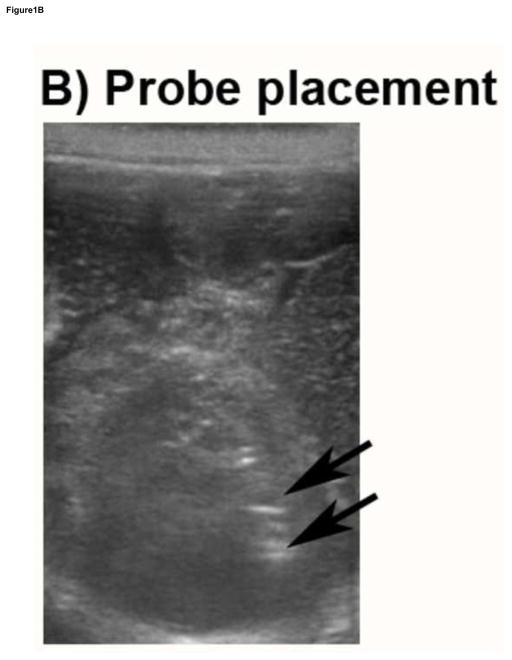

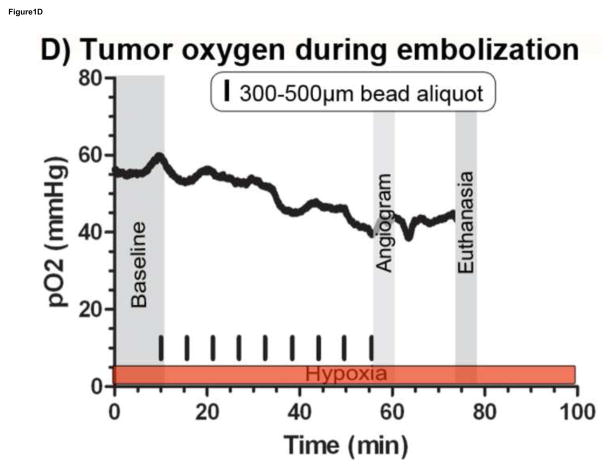

Figure 1.

Oxygen measurements of a rabbit Vx2 intrahepatic tumor during embolization to angiographic stasis. A) Proper hepatic DSA showing a hypervascular tumor (circle). B) Oxygen probe within the tumor localized by ultrasound (black arrows indicating echogenic oxygen probe in the tumor). C) DSA showing complete angiographic stasis in the hepatic arteries. D) Oxygen measurements obtained during embolization with 300–500μm beads (0.5cc aliquots every 5 minutes) demonstrating that pO2 ≤5mm Hg was not achieved following embolization to angiographic stasis.

All groups received a similar total volume of embolic suspension except the 300–500 micron group (p<0.05 for 300–500 μm group compared to all other groups). The bead suspension volumes delivered were 8.3 ± 0.6, 6.5 ± 1.2 and 3.6 ± 0.4cc for the 70–150 μm, 100–300 μm and 300–500 μm bead groups, respectively. There was a general trend to use a smaller diluted embolic volume for larger bead diameters to achieve angiographic stasis, but an angiogram was not performed after each aliquot injection to determine the exact volume required. The mean sedimented volume of embolic administered was 0.5ml, 0.3ml, and 0.2ml for the 70–150 μm, 100–300 μm and 300–500 μm diameter beads, respectively.

Oxygen changes due to embolization

Oxygen probe placement in the tumor was confirmed with ultrasound (Figure 2B) and at necropsy. Apparent differences in baseline pre-treatment oxygen levels among the three treatment cohorts were not statistically significantly different. Each aliquot of beads delivered did not result in an observable oxygen change. In approximately 50% of instances, administration of individual embolic aliquots (0.5 cc of bead suspension) resulted in a <5% change in tumor oxygen tension. A representative pO2 curve obtained during an embolization procedure with 300–500μm embolics is shown in Figure 2D. Oxygen data from one animal treated with 70–150μm beads was omitted from the analysis due to an outlier value for mean pO2 <1. The oxygen tension in this single animal was observed to drop precipitously after administration of a single aliquot of microspheres; although additional microspheres were administered, partial catheter occlusion of the hepatic artery was suspected and confirmed angiographically

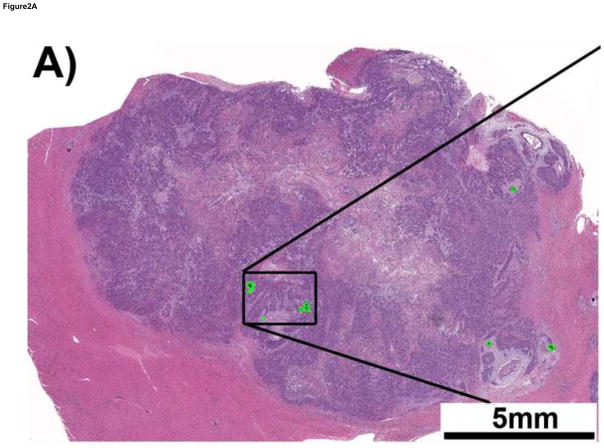

Figure 2.

Histological evaluation of embolization bead accumulation into Vx2 tumors. A) A representative H&E image of a Vx2 intrahepatic tumor that was embolized to angiographic stasis (70–150μm beads). The beads (dark purple) are encircled with green to make them more apparent at this low magnification. B) and C) are regions of the tumor that are occupied by beads; the boxes illustrate the zoomed regions. D) The per cent tumor area occupied by beads for each of the embolization bead sizes(mean ±SEM; n=3–4); 0.0937±0.0204 (70–150 μm), 0.0472±0.0174(100–300 μm), 0.000604±0.000604 (300–500μm); * indicates p<0.05.

Overall, a trend toward more frequent achievement of hypoxia (defined as measured tissue oxygen ≤5mm Hg) at angiographic stasis was observed with smaller diameter beads than larger bead diameters as shown in Table 1. The influence of the size of the embolic on the hypoxia outcome failed to demonstrate statistical significance (p=0.2727). Additionally, no significant difference was observed with pair-wise comparisons of the different bead diameter treatment groups. All bead diameters resulted in a similar absolute reduction (p=0.8013) and percent change (drop) in oxygen (p=0.3001) as show in Figure 1B and 1C. Using the hypoxic pO2 defintion of <5mm Hg, only one animal studied demonstrated significant hypoxia following embolization to flow stasis (70–150μm microsphere cohort).

Table 1.

Number of Tumors with Oxygen Measurements Approximating 5mm Hg at Angiographic Flow Stasis

| Bead Diameter | pO2≤5mm Hg | pO2>5mm Hg |

|---|---|---|

| 70–150 micron | 1 | 2 |

| 100–300 micron | 0 | 4 |

| 300–500 micron | 0 | 4 |

No significant main effect (p > 0.99)

No significant trend in hypoxic proportions p = 0.2727)

Histological evaluation

Histological evaluation of the Vx2 tumors (Figure 3) showed that there was a significant influence of embolic diameter on accumulation within the tumor (p=0.007). The percent area of the tumor occupied by embolics was significantly greater for the 70–150μm roup compared to the 300–500μm group (p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons).

Discussion

There is considerable variation in the reported critical thresholds for the pO2 in tissue below which vital cellular functions cease (1,14–16). In vitro studies have shown that oxidative phosphorylation for ATP can still take place despite cellular pO2 of 0.5–10mm Hg ((14–16). Höckel and Vaupel reported critical pO2 thresholds for solid tumors and concluded that below a pO2 of 8–10mm Hg detrimental changes in metabolic functions resulted (1). Vaupel et al (17), have identified significantly different metabolic energy status in animal tumors with median pO2 <10 mm Hg compared to those with median pO2 >10 mm Hg. These authors also found on average, median pO2 values < 10 mmHg coincided with intracellular acidosis, ATP depletion, a drop in energy charge and rising Pi levels. Carreau et al (18) describe median resting liver oxygenation status of 30mmHg, with 5% below HF5 (meaning 5% of normal liver readings are below 5mm Hg), and 13 % of normal liver readings are below HF10 (10mmHg). Using standard statistical rationale, a threshold level of 5 mmHg would yield more robust post-embolization results due to less “noise” from expected low normal liver values. We defined tumor hypoxia at ≤5mm Hg in order to document a post-treatment effect attributable to embolization which might be more universally applicable to other liver tumors, but we observed a similarly significant trend related to embolic diameter using a <10mm Hg oxygen pressure threshold.

Our study was designed to evaluate the effect of the embolic size upon the development of tumor hypoxia at angiographic flow stasis following embolization. Importantly, pO2 was measured during the embolization procedure to monitor the dynamic change in oxygenation. We observed that the diluted volume of embolic required to achieve the angiographic stasis endpoint was similar for all groups except for the 300–500μm diameter embolic, likely a result of more rapidly achieved proximal vessel obstruction with the larger beads. This proposed difference is supported by the histological observation that very few 300–500 μm embolic were observed within tumors in comparison to smaller diameter beads. Among the embolic diameters tested, no trend was observed for the greater occurrence of tumor hypoxia with the most distal embolic delivery (i.e. smaller diameter embolics were more frequently found in the tumor). It is important to remember, however, that the influence of embolic size on distribution within the vasculature of a rabbit tumor is not directly comparable with the human situation (19).

The tumor pO2 following embolization is related to 1) the degree of target vessel occlusion, 2) the presence of collateral circulation to the affected tissues, 3) the oxygen content of the perfusing blood and 4) the rate of oxygen consumption by the affected tissues. Although all sizes of embolics s caused target vessel (proper hepatic artery) stasis, differences in tissue perfusion may occur as a consequence of persistent flow despite embolization, portal blood flow not embolized, and the development of collateral circulation that is too small to be resolved angiographically. Cho and Lunderquist performed embolization of the hepatic artery in rabbits with a Gelfoam powder suspension to angiographic flow stasis (20). They determined by microscopy that no vessels smaller than 50μm in diameter appeared to be occluded. However, in 3/5 animals, they detected arterial perfusion of the liver occurring one hour after embolization from microcollaterals including capsular branches, the peribiliary arterial plexus and the vasa vasora of the portal vein. Thus, it could be expected that particulate embolization of the hepatic arteries in the Vx2 model would result in significant tumor hypoxia if the particles occluded the smallest vessels (<50 μm) which might be supplied by microcollaterals. It is possible that collateral vessels described by Cho and Lunderquist could be responsible for the continued oxygenation of Vx2 tumors embolized with 70–150μm, 100–300μm and 300–500μm diameter embolics, as flow stasis and final oxygen measurements were obtained approximately one hour after the start of embolization in our experiments. Alternatively, in the case of the larger diameter embolics a small degree of antegrade flow in the hepatic artery may have persisted which was not detectable by contrast arteriography, leading to oxygen measurements exceeding our hypoxia threshold in these groups.

There is a trend toward using smaller diameter embolics for bland embolization or chemoembolization of tumors in practice, although evidence for enhanced efficacy is sparse (8, 21). More distal drug delivery attributable to smaller embolics has been proposed for hepatic chemoembolization with drug-eluting embolics; Padia et al (8) observed a trend toward a higher incidence of EASL complete response for HCC treated with 100–300μm vs 300–500μm diameter drug-eluting embolic ss, although a statistically significant difference was not confirmed. Malagari et al (22) cite the work of Koybashai et al (23) and Wang et al(24) to suggest that more distal tumor vessel occlusion with smaller caliber embolics may avoid hypoxia-induced tumor neoangiogenesis as a mechanism for treatment failure. The results of this study in the Vx2 rabbit liver tumor model suggest that embolization with several clinically popular spherical embolic diameters yields a similar degree of residual hypoxia, which, if duplicated in human liver tumors, might help explain similar response rates observed by Padia et al(8).

This study is limited in several important respects. First, the small number of animals contributed to the limited evaluation of pair-wise bead diameter comparisons. Second, there are significant technical challenges regarding the measurement of tumoral oxygen levels in the rabbit hepatic Vx2 tumor. The animals typically have a respiratory rate of approximately sixty per minute, which results in motion of the probe tip in the tumor at a similar frequency. This motion can result in probe dislodgement; we attempted to counter this by confirming satisfactory probe tip position by sonography and during necropsy at the conclusion of each procedure. Probe motion may also cause hemorrhage, which resulted in a slow decline of measured oxygen pressure after probe placement; this pattern of oxygen measurements was excluded from analysis and required probe replacement. Third, only acute hypoxia was measured immediately following angiographic stasis and it is unknown if this hypoxia would resolve over additional time with the opening and development of collaterals. Fourth, the point based oxygen measurements do not permit any conclusion regarding the volume of tumor tissue experiencing profound hypoxia after embolization. Fifth, the study methodology provides direct measurement of tumor oxygen pressure, but not an assessment of the biological effects of hypoxia.

The results of this study suggest that transarterial embolization using spherical embolics with different diameters yields measureable sublethal levels of hypoxia in the selected animal liver tumor model. Future studies will address the question of the ideal size for micro-embolics in clinical practice, and severity and distribution of hypoxia in addition to delivered drug dose will need to be considered. Although somewhat speculative, a better understanding and localization of the dynamic process of focal hypoxia could have important treatment implications. Correlation of hypoxia with cross-sectional imaging features could help develop and validate surrogate imaging features of hypoxia (or lack of hypoxia) with the added potential for implementation during the TACE procedure itself.

This knowledge could guide direction of adjunctive therapy during the procedure by illustrating where to target a catheter, blood supply, or ablation needle towards tumor tissue at risk for under-treatment. Such surrogate imaging biomarkers could help optimize TACE or TAE to conform to a specific patient’s or tumor’s features, potentially personalizing the TACE process.

Table 2.

Number of Tumors with Oxygen Measurements Approximating 10mm Hg at Angiographic Flow Stasis

| Bead Diameter | pO2 ≤10mm Hg | pO2 > 10mm Hg |

|---|---|---|

| 70–150 micron | 1 | 2 |

| 100–300 micron | 1 | 3 |

| 300–500 micron | 0 | 4 |

No significant main effect (p = 0.71)

No significant trend in hypoxic proportions (p = 0.3818)

Table 3.

Tumor oxygen before and after embolization to angiographic stasis for each spherical embolic size

| 70–100μm | 100–300μm | 300–500μm | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Tumor Oxygen (mm Hg) (mean ± SD)a | 52.4 ± 18.3 | 54.5 ± 14.7 | 46.0 ± 16.5 | 0.758 |

| Absolute Change in Tumor Oxygen (mm Hg) (mean ± SD)b | 24.3±9.0 | 29.1±1.8 | 19.9±9.3 | 0.658 |

| Percent Change in Tumor Oxygen (percent)(mean ± SD)c | 55.9±41.6 | 56.0±13.0 | 35.4±41.4 | 0.368 |

Mean baseline pO2 measured 5min prior to the first embolic aliquot delivery

The total change in pO2 measured 5min after the last embolic aliquot was delivered

The percent change in pO2 observed normalized to the respective baseline pO2 measurement

Table 4.

Final oxygen measurements obtained five minutes following embolization to complete flow stasis in all study subjects

| Subject No. | Bead Diameter | Baseline pO2(mm Hg) | Postembolization mean pO2(mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G113 | 70–150μm | 42.72 | 12.00 |

| G253 | 70–150μm | 73.57 | 67.20 |

| L62 | 70–150μm | 41.04 | 5.30 |

| L117 | 100–300μm | 55.72 | 28.62 |

| L78 | 100–300μm | 59.13 | 28.89 |

| L33 | 100–300μm | 34.00 | 8.36 |

| L73 | 100–300μm | 68.95 | 35.39 |

| L81 | 300–500μm | 45.14 | 10.42 |

| L80 | 300–500μm | 59.22 | 24.71 |

| L65 | 300–500μm | 56.62 | 42.53 |

| L57 | 300–500μm | 23.05 | 26.97 |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Center for Interventional Oncology in the Intramural Research Program (ZID BC 011242-06) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH and Biocompatibles BTG are parties to a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. This research was performed while M.R.D was at the Center for Interventional Oncology at NIH but M.R.D. is now a paid employee of Biocompatibles Inc. A.L.L. is a paid employee of Biocompatibles UK Ltd. We thank the Division of Veterinary Resources staff for their expertise and assistance with the animal studies, Dr. Mariam Anver and the National Cancer Institute Pathology/Histotechnology Laboratory Staff for assistance with histological sample preparation, and Dr. Robert Wesley of the NIH for assistance in statistical analyses. Also, we thank Drs. Jeff Geschwind, Eleni Liapi and others from Johns Hopkins University for providing Vx2 cells and propagation expertise.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hockel M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. JNCI. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davda S, Bezabeh T. Advances in methods for assessing tumor hypoxia in vivo: implications for treatment planning. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2006;25(3):469–80. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang B, Zheng C, Feng G, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in liver tumors after transcatheter arterial embolization in an animal model. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2009;29(6):776–781. doi: 10.1007/s11596-009-0621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virmani S, Rhee TK, Ryu RK, et al. Comparison of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a expression before and after transcatheter arterial embolization in rabbit Vx2 liver tumors. JVIR. 2008;19:1483–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vauple P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreher MR, Sharma KV, Woods DL, et al. Radiopaque drug-eluting beads for transcatheter embolotherapy: experimental study of drug penetration and coverage in swine. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2012;23(2):257–64. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doppman JLGM, Kahn R. Proximal versus peripheral hepatic artery embolization experimental study in monkeys. Radiology. 1978;128(3):577–88. doi: 10.1148/128.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padia SA, Shivaram G, Bastawrous S, et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting bad chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of small-versus medium-size particles. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranjan A, Jacobs GC, Woods DL, et al. Image-guided drug delivery with magnetic resonance guided high intensity focused ultrasound and temperature sensitive liposomes in a rabbit Vx2 tumor model. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2012;158(3):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KH, Liapi E, Ventura VP, et al. Evaluation of different calibrated spherical polyvinyl alcohol microspheres in transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: VX2 tumor model in rabbit liver. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2008;19(7):1065–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geschwind JF, Artemov D, Abraham S, et al. Chemoembolization of liver tumor in a rabbit model: assessment of tumor cell death with diffusion-weighted MR imaging and histologic analysis. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2000;11(10):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collingridge DR, Young WK, Vojnovic B, et al. Measurement of tumor oxygenation: a comparison between polarographic needle electrodes and a time-resolved luminescence-based optical sensor. Radiat Res. 1997;147:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun C-J, Chao LI, Hai-Bo LV, et al. Comparing CT perfusion with oxygen partial pressure in a rabbit Vx2 soft-tissue tumor model. J Radiat Res. 2014;55:183–190. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrt092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall RS, Koch CJ, Rauth AM. Measurement of low levels of oxygen and their effect on respiration in cell suspensions maintained in an open system. Radiation research. 1986;108(1):91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starlinger H, Lubbers DW. Methodical studies on the polarographic measurement of respiration and “critical oxygen pressure” in mitochondria and isolated cells with membrane-covered platinum electrodes. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 1972;337(1):19. doi: 10.1007/BF00587868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robiolio M, Rumsey WL, Wilson DF. Oxygen diffusion and mitochondrial respiration in neuroblastoma cells. The American journal of physiology. 1989;256(6 Pt 1):C1207–C1213. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.6.C1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaupel P, Schaefer C, Okunieff P. Intracellular acidosis in murine fibrosarcomas coincides with ATP depletion, hypoxia, and high levels of lactate and total Pi. NMR Biomed. 1994;7:128–136. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molls M, Vaupel P, Nieder C, Anscher MS, editors. The impact of tumor biology on cancer treatment and multidisciplinary strategies. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namur J, Citron SJ, Sellers MT, et al. Embolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug-eluting beads: doxorubicin tissue concentration and distribution in patient liver explants. J Hepatol. 2011;55(6):1332–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho KJ, Lunderquist A. Experimental hepatic artery embolization with Gelfoam powder. Microfil perfusion study of the rabbit liver. Investigative radiology. 1983;18(2):189–193. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198303000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deipolyi AR, Oklu R, Zhu AX, et al. Safety and efficacy of 70–150 μm and 100–300 μm drug-eluting bead transafterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. JVIR. 2015;26(4):516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malagari K, Pomoni M, Moschouris H, et al. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with HepaSphere 30–60μm. Safety and efficacy study. CVIR. 2014;37:165–175. doi: 10.1007/s00270-013-0777-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koybashai N, Ishii M, Ueno Y, et al. Co-expression of Bcl-2 protein and vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinomas treated by chemoembolization. Liver. 1999;19(1):25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Xu H, Gao Zq, Ning HF, Sun YQ, Cao GW. Increase expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(5):523–529. doi: 10.1080/02841850801958890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]