Abstract

Introduction

Although a considerable proportion of Asians in the USA experience depression, anxiety and poor sleep, these health issues have been underestimated due to the model minority myth about Asians, the stigma associated with mental illness, lower rates of treatment seeking and a shortage of culturally tailored mental health services. Indeed, despite emerging evidence of links between psychosocial risk factors, the gut microbiome and depression, anxiety and sleep quality, very few studies have examined how these factors are related in Chinese and Korean immigrants in the USA. The purpose of this pilot study was to address this issue by (a) testing the usability and feasibility of the study’s multilingual survey measures and biospecimen collection procedure among Chinese and Korean immigrants in the USA and (b) examining how stress, discrimination, acculturation and the gut microbiome are associated with depression, anxiety and sleep quality in this population.

Method and analysis

This is a cross-sectional pilot study among first and second generations of adult Chinese and Korean immigrants in the greater Atlanta area (Georgia, USA). We collected (a) gut microbiome samples and (b) data on psychosocial risk factors, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance using validated, online surveys in English, Chinese and Korean. We aim to recruit 60 participants (30 Chinese, 30 Korean). We will profile participants’ gut microbiome using 16S rRNA V3-V4 sequencing data, which will be analysed by QIIME 2. Associations of the gut microbiome and psychosocial factors with depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance will be analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics, including linear regression.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University (IRB ID: STUDY00000935). Results will be made available to Chinese and Korean community members, the funder and other researchers and the broader scientific community.

Keywords: public health, social medicine, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to examine psychosocial and biological mechanisms underlying mental health and sleep quality among Chinese and Korean immigrants.

The study will collect data among Asians in the USA, who have been historically under-represented in biomedical research.

The study is timely, as the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly increased stress and racial discrimination among Asians in the USA.

The study uses a state-of-the-art measure of lifetime stress exposure (ie, the Stress and Adversity Inventory) and several other culturally valid assessment instruments.

The cross-sectional study design will limit the testing of directionality and causal associations but will help inform future longitudinal research.

Introduction

Asians are the fastest-growing racial group in the USA,1 with Chinese (23%) and Koreans (9%) combined representing the largest subgroup of Asians. The increasing size of the Asian population nationwide calls for more attention to be paid to the unique health needs of this population, which has been historically underestimated and under-represented, partly because of the ‘model minority myth’ that characterises Asians as being relatively successful with few problems.2 However, Asian Americans experience many mental health problems including depression and anxiety in high proportions,3 4 making this topic an important public health priority, especially during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Although depressive and anxiety disorders are the most common and debilitating psychiatric illnesses in the US adult population,5 6 the literature investigating these illnesses among Asians is limited.3 This has occurred despite the fact that depression is the most frequently diagnosed mental disorder in Asian Americans. The pooled prevalence rate of depression ranges from 26.9% to 35.6%3 and the lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 9.1%.4 Asian Americans, as compared with their white peers, tend to manifest more prevalent, persistent and recurrent depressive symptoms.3 4 7 This is a critical point, as depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and can lead to other severe health problems, including chronic physical health conditions8 9 and suicide. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death for Asian Americans aged 15–24 years.10 Additionally, anxiety disorders—including panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder—are experienced by 10.2% of Asian Americans.4 Moreover, due to the stigma attached to mental illness and the lack of culturally competent mental health services, Asian Americans are less likely than their white peers to ask for help and seek treatment,4 8 which further contribute to the racial and ethnic disparities in mental health outcomes that are evident for Asian Americans living in the USA.

Understanding depression and anxiety among Asian immigrants is complicated by the fact that their mental health is determined by several factors, including chronic stress exposure, racial discrimination and level of acculturation.3 7 11 It has been reported that the more Asian Americans are exposed to discrimination and acculturative life stress, the more likely they are to experience depression and anxiety.12 Additionally, Asian Americans experience racial discrimination on multiple levels (ie, cultural, structural, interpersonal and internalised).13–15 Moreover, racial discrimination and aggression toward Asians has substantially increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Relative to white, black and Hispanic peers, for example, Asian Americans are more likely to report that since the COVID-19 pandemic, people acted as if they were uncomfortable around them (39%), that they have been subjected to slurs or jokes (31%) and that they have feared someone might threaten or physically attack them (26%).16 Finally, 60% of Asian immigrants, including those with high educational attainment, experience acculturative stress associated with learning and fitting into a new culture, concerns about legal status, cultural conflicts and language barriers.17

Given the complexity of the psychosocial determinants underlying depression and anxiety, it is challenging to identify Asian Americans at high risk of developing these psychiatric disorders, particularly given that they are more reluctant to disclose their mental health status to others.3 17 Thus far, a few biomarkers have been used to predict depression, including cytokines and inflammatory markers, oxidative stress markers, endocrine markers, energy balance hormones, genetic/epigenetic factors and structural and functional brain imaging.18 Emerging evidence suggests that the gut microbiome also plays an important role in human mental health via the microbiome–gut–brain axis, a bidirectional network that enables the gut microbiome to affect the brain and mental health through immune, neural and hormonal pathways.19 The gut microbiome is the collection of all genomes of the microbes in the human gastrointestinal tract.20 The human gut hosts tens of trillions of microbes, representing 500 species on average.21 22 Notably, it is heavily influenced by an individual’s sociodemographic characteristics, changes in diet, lifestyle, stress and geographic environment, all of which represent significant risk factors for depression and anxiety among Asian immigrants.23 24 More specifically, migration from non-Western nations to the USA is associated with a loss in the gut microbial diversity and function in a manner that may predispose Asian immigrants to high risk of metabolic diseases and mental disorders.23 Therefore, subsequent changes in both the diversity and function of the gut microbiome after migration provide a unique opportunity to study how living environment in the USA represents an external stimulus that affects immigrants’ mental health in the context of stress, discrimination and acculturation.23 25 26

Finally, when exploring the impact of psychosocial determinants and the gut microbiome on mental health, it is important to address sleep quality.27 Asian Americans are more likely to report short sleep duration than their white peers (33% vs 28%).28 Sleep disturbance is one of the most prominent symptoms experienced by those with depression and anxiety disorder and is incorporated into the diagnostic criteria and definitions of these disorders.29–31 Moreover, chronic stress frequently manifests as increases in sleep disturbance and/or changes in sleep patterns.32 Daily racial microaggressions have been associated with poorer sleep quality and shorter sleep duration the following day among Asian Americans.33 Additionally, the gut microbiome has been associated with sleep disturbance and metabolic disorders.34 35 Considered together, therefore, it is critical to examine psychosocial and biological pathways that might underlie depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance in Asian Americans in the context of migration and acculturation among Asian immigrants in the USA.

Present study

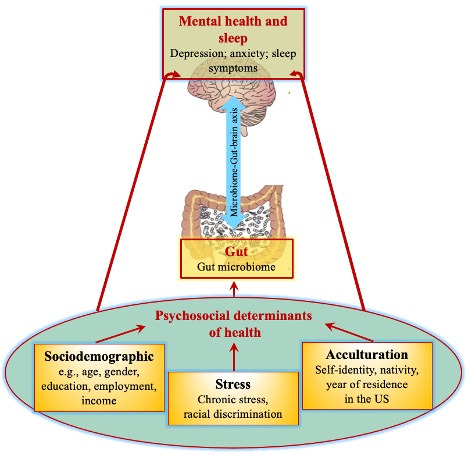

The goal of the present study (1 June 2020–31 May 2021) is to study psychosocial and biological mechanisms of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance to help inform early prevention and personalised treatment strategies for these conditions for Asian immigrants who commonly underuse mental health services. Of many Asian subgroups, we chose to focus on Chinese and Korean as the target populations for two main reasons: (a) together, they represent the largest subgroup of Asian Americans in the USA, as well as in the Greater Atlanta area where the study is located, and (b) as a result, they experience the greatest proportion of disease burden associated with depressive and anxiety disorders among Asian Americans. This work is guided by the conceptual framework presented in figure 1. In conducting this research, we have two primary aims: (a) test the usability and feasibility of the study’s multilingual survey measures and biospecimen collection procedures among Chinese and Korean immigrants living in the USA and (b) collect pilot data for a subsequent larger study to examine the roles that psychosocial factors and the gut microbiome play in depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance in this population.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Method

Study design and participants

An observational, cross-sectional study design will be used. The inclusion criteria for the sample population are: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) self-identify as Chinese or Korean; (3) live in the greater Atlanta area in Georgia, USA, and (4) can read and write English, traditional and simplified Chinese or Korean. Because this study aims to sample first and second generation Chinese and Korean immigrants, we define first generation immigrants as those who are foreign born living in the USA, regardless of the duration and purpose of residence in the USA, and we define second generation immigrants as those who are USA born living in the USA. The exclusion criteria include having used antibiotics during the past month and being a pregnant woman, as they undergo considerable psychosocial and biological changes during pregnancy that can affect their physical and mental health status. We will sample a total of 60 participants, including 30 Chinese and 30 Korean. This is based on data showing that a sample size of 24–40 is optimal as a pilot study for helping inform subsequent research.36 37

Recruitment

First, we will use both online and offline recruitment strategies. The former will involve posting study advertisements on social media (eg, Twitter, Facebook), craigslist, ResearchMatch and Chinese and Korean online communities (eg, online Chinese Church Group via WeChat, Georgia Tech Korean Student Association), websites and blogs. The latter recruitment strategy will involve working with community partners, including a Korean church in Atlanta, an Emory Clinic in Atlanta and a local clinic in Johns Creek, Georgia. They will introduce our study to their Chinese or Korean congregation, patients or members. This recruitment strategy is consistent with prior work showing that collaborating with gatekeepers is one of the most effective ways to reach and conduct high-quality research with Asian populations in the USA.38

Patient and public involvement

We have established an advisory board comprised of not only academics with expertise in immigrant populations and mental health but also community members from churches and clinics. The demographic characteristics of the advisory board members are: (1) professor (male, Caucasian, expertise: mental health), (2) professor (female, Caucasian, expertise: international social demography), (3) pastor (male, Korean), (4) professor/clinician #1 (male, Caucasian, medical doctor) and (5) clinical instructor/clinician #2 (female, Chinese, nurse practitioner). The community members are Chinese or Korean themselves or serve Chinese or Koreans in the Greater Atlanta area. The goal of the advisory board is to demonstrate and improve the research team’s engagement with and accessibility to the target population. The board members in academia will share their knowledge and experience of working with racial/ethnic minority populations and those in communities will provide the study’s information and refer interested individuals to the research team. The board will convene as a group 1–2 times a year via conference calls, although the research team can contact individual board members for consultation as needed. The agenda of the advisory board meetings will include (but not be limited to) recruitment strategies to reach out to Chinese and Korean communities, motivational strategies, how each board member can help connect the communities to the research team and the board’s expectations after their service (eg, authorship in papers, sharing the study findings with the community members they serve).

Data collection

First, when potential participants contact the research team directly or via referral, the research staff will email them back to make an appointment. Then, on the scheduled date and time, we will call them to screen their eligibility and obtain their verbal consent to participate in the study. To accomplish this, we have hired and trained culturally matched research staff members who are fluent in English, Chinese or Korean to perform the consent process in the participant’s preferred language. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there will not be any in-person interactions with participants. Second, on obtaining participants’ informed consent and agreement to participate in the study, the research team will send an online survey link via email. Participants will administer the survey in their preferred language. During the survey, participants will provide their name, mailing address, phone number and email address. Participants’ names and mailing addresses will be used to ship the gut microbiome data collection kits, which will include pictorial and written instructions in English, Chinese or Korean. Compensation for participating will be provided after completing the study. The compensation will be prorated: participants who complete both the online survey and specimen collection will receive a $30 e-gift card, whereas those completing only the online survey will receive a $10 e-gift card. E-gift cards will be emailed to the email addresses provided by the participants.

Consistent with ethical guidelines, participants will be allowed to opt out of any parts of the data collection that they wish (eg, specific online survey questions, specimen collection) and continue with other parts of the study protocol as they wish. If a participant does opt out, they will be encouraged to provide a reason so we can better understand the situation. Their feedback on the usability of the study methods will help the research team modify and tailor the current data collection procedure further to Chinese and Korean immigrants for future research. If participants withdraw their consent or if the research team learns that a participant does not meet the inclusion or exclusion criteria during the study, data collection will be stopped and all collected biological material and data will be destroyed.

Self-report measures and their translation

This study will use the battery of validated instruments described in table 1. The battery will include the Demographics Short Form (DSF), Suinn-Lew Self Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA), Acculturative Stress Scale, Subtle and Blatant Racism Scale for Asian Americans (SABR-A2), Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN), Pandemic Stress Index (PSI), PROMIS Short Form—Depression, PROMIS Short Form–Anxiety, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and PrimeScreen, a brief dietary screening tool. All these instruments have already been validated and are widely used in English.

Table 1.

Study measures

| Variable | Measure | Instrument | Need for translation |

| Sociodemographic and clinical factors | Demographics Short Form (eg, sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviours, medical history) | Yes | |

| Psychosocial factors | Acculturation | Suinn-Lew Self Identity Acculturation Scale | Yes |

| Demographic Short Form (eg, foreign-born status, duration of US residence, age at immigration) | Yes | ||

| Stress | Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults | Yes | |

| Pandemic Stress Index | Yes | ||

| Acculturative Stress Scale | No | ||

| Subtle and Blatant Racism Scale for Asian Americans | Yes | ||

| Diet | PrimeScreen Survey | Yes | |

| Biological factor | Gut microbiome | Faecal specimen | Yes (instructions) |

| Mental health outcomes | Depression | PROMIS Short Form–Depression | No |

| Anxiety | PROMIS Short Form–Anxiety | No | |

| Sleep symptoms | Sleep quality | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | No |

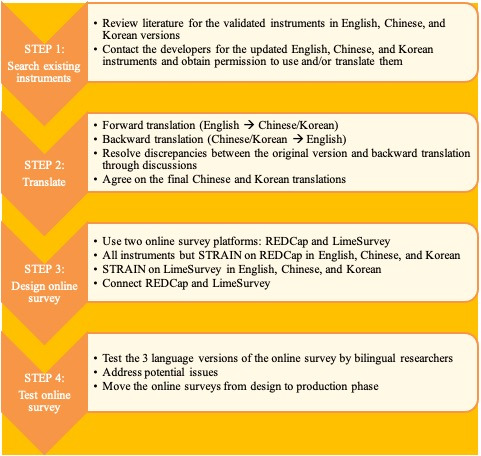

For measures that have not yet been translated into Chinese and/or Korean, we contacted the instrument developers to obtain permission to use and translate them. We translated SABR-A2, Adult STRAIN, PSI and PrimeScreen into Chinese and Korean following the guideline of cultural translation and adaptation of instruments from the WHO, which involves: forward translation, expert panel back translation, pretesting and cognitive interviewing and final version.39 Our instrument translation team included three research team members and one external member who were bilingual (fluent in English and Simplified or Traditional Chinese or Korean) with PhD degrees in nursing or sociology and extensive experience with Asian immigrants, demography, mental health and stress. Specifically, after one member translated all of the instruments into Chinese or Korean versions, another member translated them back into English. Then, both members compared the original English and back-translated English versions to evaluate the quality of the translation. Discrepancies in the translation and meanings were solved by consensus discussions between these two members to ensure conceptual equivalence across the translations. The steps taken as part of this multilingual survey development process are depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Multilingual survey development and testing process.

DSF

The DSF is a 27-item questionnaire used to collect participants’ general sociodemographic and health characteristics. Most of the items were derived from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Data Elements.40 The questionnaire has been used in an ongoing study sponsored by the NIH (1K99NR017897-01, PI: JB). The sociodemographic variables include age, gender, self-identified race, marital status, living arrangement, immigration, religious belief, education and household income. Health-related variables include height, weight, lactose intolerance, use of antibiotics and probiotics, disease history and the use of mental health services.

SL-ASIA

The original version41 of the SL-ASIA is a 26-item questionnaire used to assess a person’s level of acculturation, specifically historical background and cultural identity. We chose five items to measure participants’ preference for food, music, custom, language proficiency and the racial composition of close friends on a 5-point Likert Scale. This adapted version has been used in other studies.42 We will average the assigned values across the questions into a total acculturation score. A higher total score indicates more Westernisation or acculturation.

Acculturative Stress Scale

The Acculturative Stress Scale is a 36-item questionnaire used to measure acculturative stress on a 5-point Likert Scale. Not counting the miscellaneous group, there are six subscales assessing perceived discrimination, homesickness, perceived hate, fear, stress due to change/culture shock and guilt. In this study, an 8-item questionnaire from two domains of task-oriented stress (three items) and emotion-oriented stress (five items) will be adopted. Items for task-oriented stress include: ‘I feel nervous when communicating in English’ and ‘I feel uncomfortable adjusting to new foods’. Sample items for emotion-oriented stress include: ‘Homesickness bothers me’ and ‘I feel sad living in unfamiliar surroundings’. Acculturative stress in the adapted instrument will also be measured on a 5-point Likert Scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Individual scores will be summed to create a total score for each domain where a task-oriented stress score can range 0–12, and an emotion-oriented stress score can range 0–20. Higher scores indicate greater levels of acculturative stress. The adapted instrument has shown high internal consistency for both scales tested among Korean American older adults (Cronbach’s α=0.73 for task-oriented stress and 0.87 for emotion-oriented stress).43

SABR-A2

The SABR-A2 is a 10-item questionnaire that asks about personal experience of subtle and blatant racism.44 The subtle racism subscale (four items) refers to instances of discrimination due implicitly to racial bias or stereotype (eg, treated differently, overlooked). The blatant racism subscale (four items) refers to instances of discrimination due explicitly to racial bias or stereotype (eg, called names, commented about English proficiency). However, 2 out of 10 items were not included in this study because according to the instrument’s author, they were developed as exploratory items. Responses are measured on a 5-point Likert Scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). All eight items will be averaged into a total racism score, and each set of the four items will be averaged into a subtle and blatant racism score, with higher scores indicating greater perceived racism. The internal consistency of the total, subtle and blatant racism (sub)scales tested among self-identified Asian American undergraduate students was 0.84–0.88, 0.76–0.82 and 0.77–0.82, respectively.44

Adult STRAIN

The Adult STRAIN45 measures a person’s lifetime exposure to 55 different types of acute (eg, deaths of relatives, job loss) and chronic stressors (eg, persistent health, work, relationship, financial problems) (see https://www.strainsetup.com). Participants’ responses will be used to calculate a standard set of 20 lifetime stress exposure scores, which are based on the type of stressors experienced, when they were experienced, their primary life domain and their core social-psychological characteristic. More specifically, these summary score data will include the following computed variables: lifetime stressor count, lifetime stressor severity, early life (before age 18) stressor count, early life (before age 18) stressor severity, adulthood stressor count, adulthood stressor severity, lifetime count of acute life events, lifetime count of chronic difficulties, lifetime severity of acute life events, lifetime severity of chronic difficulties, lifetime stressor count and severity by primary life domain (ie, housing, education, work, treatment/health, marital/partner, reproduction, financial, legal/crime, other relationships, death, life-threatening situations, possessions) and lifetime stressor count and severity by core social-psychological characteristic (ie, interpersonal loss, physical danger, humiliation, entrapment, role change/disruption). Higher scores indicate greater life stress exposure across these categories. The STRAIN has been extensively validated in relation to a variety of cognitive, mental and physical health outcomes46–50 and has excellent test–retest reliability over time for the main stress exposure outcomes (r values≥0.904).45

PSI

The PSI51 is a 3-item measure of behaviour changes and stress that individuals may have experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The questions are: ‘What are you doing/did you do during COVID-19 (coronavirus)?’ with a checklist of items about behaviours, such as social distancing; ‘How much is/did COVID-19 (coronavirus) impact your day-to-day life?’ and ‘Which of the following are you experiencing (or did you experience) during COVID-19 (coronavirus)?’ with a checklist of items about emotional distress, substance use, sexual behaviour, financial stress, stigma and support.

PROMIS Short Form–Depression

The 28-item PROMIS Depression Item Bank assesses negative mood (eg, sadness, guilt), negative views of the self (eg, self-criticism, worthlessness), negative social cognition (eg, loneliness, interpersonal alienation) and decreased positive affect and engagement (eg, loss of interest, meaning, and purpose).52 Of these 28 items, six have been selected to create the PROMIS Short Form–Depression, which has high reliability and precision that is comparable to the original 28-item scale.52 The 6-item scale assesses depressive symptoms over the past 7 days and has response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The raw scores will be transformed into T scores, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms.52

PROMIS Short Form–Anxiety

The PROMIS Anxiety Item Bank assesses self-reported fear, anxious misery, hyperarousal and somatic symptoms related to arousal.53 The PROMIS Short Form–Anxiety includes six items, which have reliability and precision estimates that are high and comparable to the full item bank.53 The correlation of the adult full bank with the 6-item short form is between 0.90 and 0.95. The six items assess anxiety symptoms over the past 7 days and have response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The raw scores will be transformed into T scores, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety.53

PSQI

The PSQI is a 10-item scale including 19 self-rated questions. It assesses sleep quality over a 1-month time interval. The instrument evaluates both objective (eg, how often participants wake up during the night) and subjective aspects of sleep quality (eg, how rested they typically feel after a night of sleep). These 19 questions are combined to form seven ‘component’ scores, each of which has a range of 0–3 points, from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty). Then, the seven component scores are summed to create a global PSQI Score, ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality. In primary insomnia patients, the overall PSQI global score exhibited an excellent test–retest reliability of 0.87.54 The total score of the Korean version of PSQI showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.84).55

PrimeScreen

The PrimeScreen is a 23-item dietary assessment questionnaire.56 This self-reported measure evaluates the average frequency of consumption of specified foods and food groups, as well as 13 nutrients (eg, vitamin and supplements) over the past 6 months.56 57 Each item has five response categories: ‘less than once per week’, ‘once per week’, ‘2–4 times per week’, ‘nearly daily or daily’ or ‘twice or more per day’. This measure has great reliability and validity for use in adults aged 19–65 years, including excellent reproducibility (r=0.70) and comparability with the Semiquantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (SFFQ) in foods and food groups (r=0.61), as well as excellent reproducibility (r=0.74) and comparability (r=0.60) with the SFFQ for nutrients.56

Gut microbiome

To profile the gut microbiome, we will collect faecal specimens using the sample collection procedure used in the Human Microbiome Project protocol.58 Specifically, we will coach participants to use the home-based specimen collection kits to obtain faecal samples. The kits will include one pair of gloves, one toilet basin and one biohazard bag with four small stool collection tubes (Fisher Scientific Co. LLC., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA). Faecal samples will be collected using pictorial instruction. Specifically, after voiding stool into the toilet basin, the participant will use the spoon in the cap of the stool collection tube to collect stool and then cap the tube. This stool specimen collection process is repeated two more times with the same voided stool specimen for a total of three tubes (one for gut microbiome analysis, one for quality control and one for backup).

All the instructions for the sample collection will be prepared in English, Chinese and Korean. On completion of the specimen collection, participants will follow the packaging instructions (eg, store in a refrigerator for 24 hours before shipping). The samples will be put in the biohazard bag and then into a padded, labelled freezer bag with an ice pack. Participants will ship the samples to the Nursing Biobehavioral Laboratory at Emory University using prepaid FedEx shipping, which takes approximately 24 hours to arrive at the lab. All faecal samples will be stored at a −80°C freezer until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and sequencing of the gut microbiome

According to the Human Microbiome Project protocol, the microbial DNA will be extracted from faecal specimens using the PowerSoil isolation kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, California, USA). The 16S rRNA V3-V4 gene regions59 60 will be extracted and sequenced. 16S rRNA amplicons will be generated using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, KK2600) and primers specific to 16S V3-V4 region of bacteria 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′)−805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). The PCR clean up will be performed using AMPure XP beads (Beckman, A63880) and indices will be attached using the Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina, FC-131-1001). Final library pools will be quantitated via qPCR (Kapa Biosystems, catalogue KK4824). The pooled library will be sequenced on an Illumina miSeq using miSeq v3 600 cycle chemistry (Illumina, catalogue MS-102-3003) at a loading density of 8 pM with 20% PhiX, at PE300 reads. This process will be conducted at the Integrated Genomics Core at Emory University. The microbial sequencing will lead to paired-end sequences for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Prior to analysis, all data will be reviewed for quality, distributions and missing data bias (eg, missing at random). Mathematical transformations will be performed when necessary to normalise scores. Descriptive statistics (eg, Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test because of the limited sample size) will be adopted to describe participants’ characteristics, as well as associations between the psychosocial and biological factors and the outcome variables (ie, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance).

For the gut microbiome data, 16S rRNA sequences will be analysed to obtain microbial diversity (ie, α-diversity and β-diversity), taxonomic composition and abundance. QIIME 2 default parameters will be used to identify amplicon sequence variants and filter the sequences quality using DADA2.61 62 Taxonomies will be assigned by the pretrained classifier using Silva. Differences between the microbiomes across samples will be characterised by α-diversity metrics (Shannon, Chao-1, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity and Pielou’s evenness) and β-diversity distances (Bray-Curtis distance, unweighted and weighted UniFrac distance). Pearson or Spearman correlations will be used to determine associations among microbial diversity indices (α-diversity and β-diversity) and the outcome variables. The principal coordinates analysis will also be used to visualise diversity patterns. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe)63 will be used to characterise the taxa differences between different levels of outcome variables: (a) Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test will be adopted to detect features with significant differential abundance between the levels of outcome variables; (b) Wilcoxon rank-sum test will be adopted to further investigate significances of taxa through a set of pairwise tests among subclasses (eg, psychosocial factors) and (c) LEfSe will estimate the effect size of each differentially abundant feature. All analyses will be conducted using QIIME 264–66 and R V.3.3.3. The statistical significance level will be set at p<0.05.

Data storage and security

All of the survey data will be managed using REDCap,67 which evaluates data errors, completeness and validation checks to ensure maximum data quality. All faecal specimens will be stored in the Nursing Biobehavioral Laboratory at Emory University. These specimens will only be used to address our research aims. All the survey data and specimens will be destroyed 3 years after the entire study is finished. The confidentiality of all data will be maintained within legal limits.

Discussion

Although numerous studies have examined risk processes associated with mental health and poor sleep, there is a distinct paucity of research on Asian immigrants in the USA, despite the fact that this population is underserved and experiences substantial mental health-related disease burden in America. To address this important issue, we will conduct the present study, which will be the first to examine psychosocial and biological mechanisms underlying depression, anxiety and sleep symptoms among Chinese and Korean immigrants in the USA. Considering that these populations are growing quickly, we expect that the findings will help advance our knowledge on racial and ethnic differences in mental health outcomes and the biopsychosocial pathways that underlie these effects.

Although these associations would be important to understand at any time, we believe these issues are particularly critical to study during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the increased rates of social conflict, discrimination and, in some cases, injustice that have been experienced by Asians in the USA during this time. Indeed, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Asian immigrants has been extensive.68 Public health measures designed to curb the spread of the virus, which have included lockdown, school and business closures and travel restrictions, have had a tremendous impact on the stress levels and mental health of the general population.69 70 Beyond this, though, Asians living in the USA have been stigmatised and victimised by media coverage perpetuating the naming of the COVID-19 virus as the ‘Chinese Virus’ or ‘Kung Flu’, which has in turn led to racial discrimination and other social threats68 that have been shown to strongly affect mental and physical health.71 The cumulative social stress and threat experienced by Asian immigrants, which include aggravated racial discrimination in addition to ongoing health, employment and financial worries, will provide a unique opportunity to better understand how psychosocial factors and the microbiome affect mental health and sleep symptoms during a time of maximal importance and relevance.

In assessing Asian immigrants’ cumulative life stress exposure, the Adult STRAIN and PSI will help assess acute and chronic stressors of participants who have been going through the pandemic for an extended period of time. Importantly, some of the measures we have selected are tailored to Asian populations, which will enable us to collect more valid and reliable data that are reflective of Asians’ lived experiences, including racial discrimination and acculturation. These culturally adapted measures will yield a unique and timely perspective on mental health and sleep outcomes in Asian immigrants.

This study has some limitations. They include a limited sample size and cross-sectional study design. The small sample size limits power and data analysis options at the more granular level (eg, stratified analysis by immigrant generation). Also, the sample limits generalisability to other Asian subgroups due to studying only Chinese and Koreans. In terms of the measures, although diet is culture specific, the PrimeScreen has not been extensively validated among Chinese or Korean populations. Despite some dietary intake not captured by the PrimeScreen, we expect its impact on the study findings to be minimal, as diet will be treated as a control variable in analyses. Lastly, the demographic characteristics may differ between those recruited online and offline. Considering many of the recruitment strategies use online platforms, the participants could be skewed toward a younger population with a shorter duration of US residence, resulting in limited variation for these data. Therefore, a future study should collect information on how participants were recruited (online vs offline) and consider this in statistical analyses. Nevertheless, looking forward, we expect this study to provide important preliminary data that can in turn be used to inform the development of a larger longitudinal study aimed at investigating associations between psychosocial and biological determinants of health, and mental health and sleep symptoms among Asian immigrants in the USA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daesung Choi for assisting the translation of survey instruments, Rema Henry for helping build the online survey and the advisory board members Kevin Park, Brooke Yang and Kathryn Yount for their feedback and support to recruit our target populations.

Footnotes

Twitter: @jasminekoaqua

Contributors: The study’s concept and design were conceived by SK, WZ, VP, VSH and JB. Author GS produced a secure online STRAIN portal, monitored stress data collection and implemented and managed the stress data collection protocol. SK, WZ and JB translated the survey instruments and other study materials into Chinese or Korean. SK, WZ, JKA, JB and CMS developed the online survey and managed the online survey platforms. SK, WZ, VP, JKA and JB were involved in participant recruitment. SK, WZ, JKA and JB collected data and consented participants. SK, WZ, JKA and JB will analyze the data and VSH and GS will guide and supervise data analysis. SK prepared the first draft of this manuscript. All authors provided critical edits, critiqued the manuscript for intellectual content and read and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: This work was supported by the Office of the Senior Vice President for Research at Emory University (Bidirectional Global Health Disparities Research Pilot Grant, JB and SK) and National Institute of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (1K99NR017897-01, 4R00NR017897-03, JB). GS was supported by a Society in Science—Branco Weiss Fellowship, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant #23958 from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation and National Institutes of Health grant K08 MH103443.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center . Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S, 2019. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/22/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/

- 2.Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, et al. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:1354–81. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HJ, Park E, Storr CL, et al. Depression among Asian-American adults in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127760. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong S, Walton E, Tamaki E, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders among Asian Americans: Nativity, gender, and sociodemographic correlates. Asian Am J Psychol 2014;5:353–63. 10.1037/a0035680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Psychiatric disorders: a global look at facts and figures. Psychiatry 2010;7:16–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke T, Schiller J, Boersma P. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2019 National health interview survey: division of health interview statistics. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams NJ, Grandner MA, Wallace DM, et al. Social and behavioral predictors of insufficient sleep among African Americans and Caucasians. Sleep Med 2016;18:103–7. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull 2014;140:774–815. 10.1037/a0035302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slavich GM. Psychoneuroimmunology of stress and mental health. In: Harkness KL, Hayden EP, eds. The Oxford Handbook of stress and mental health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020: 519–46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National center for injury prevention and control. web based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS), 2016. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 11.Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: the impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Dev Psychol 2008;44:787–800. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gee GC, Spencer M, Chen J, et al. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1984–96. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: ethnic identity and Other-Group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. J Couns Psychol 2005;52:36–44. 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Ment Health J 2006;42:555–70. 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychological Association Working Group on Stress and Health Disparities . Stress and health disparities: contexts, mechanisms, and interventions among racial/ethnic minority and low-socioeconomic status populations, 2017. Available: http://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/stress-report.aspx

- 16.Ruiz NG, Horowitz JM, Tamir C. Many black and Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid the COVID-19 outbreak: Pew research center, 2020. Available: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/07/01/many-black-and-asian-americans-say-they-have-experienced-discrimination-amid-the-covid-19-outbreak/

- 17.Nagayama Hall GC, Yee A. U.S. mental health policy: addressing the neglect of Asian Americans. Asian Am J Psychol 2012;3:181–93. 10.1037/a0029950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacimusalar Y, Eşel E. Suggested biomarkers for major depressive disorder. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 2018;55:280–90. 10.5152/npa.2017.19482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:306–14. 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012;13:701–12. 10.1038/nrn3346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Microbiol 1977;31:107–33. 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knight R, Buhler B. Follow your gut: the enormous impact of tiny microbes. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vangay P, Johnson AJ, Ward TL, et al. Us immigration Westernizes the human gut microbiome. Cell 2018;175:962–72. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan RC, Wang Z, Usyk M, et al. Gut microbiome composition in the Hispanic community health Study/Study of Latinos is shaped by geographic relocation, environmental factors, and obesity. Genome Biol 2019;20:219. 10.1186/s13059-019-1831-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montiel-Castro AJ, González-Cervantes RM, Bravo-Ruiseco G, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: neurobehavioral correlates, health and sociality. Front Integr Neurosci 2013;7:70. 10.3389/fnint.2013.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strasser B, Becker K, Fuchs D, et al. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and immune activation: peripheral measurements in psychiatric and co-morbid conditions. Neuropharmacology 2017;112:286–96. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cashion AK, Gill J, Hawes R, et al. National Institutes of health symptom science model sheds light on patient symptoms. Nurs Outlook 2016;64:499–506. 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson CL, Kawachi I, Redline S, et al. Asian-White disparities in short sleep duration by industry of employment and occupation in the US: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:552. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rumble ME, White KH, Benca RM. Sleep disturbances in mood disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2015;38:743–59. 10.1016/j.psc.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MJ, Peterson MJ. Sleep disturbances in depression. Sleep Med Clin 2015;10:17–23. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox RC, Olatunji BO. A systematic review of sleep disturbance in anxiety and related disorders. J Anxiety Disord 2016;37:104–29. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NPR/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health . The burden of stress in America, 2014. Available: https://media.npr.org/documents/2014/july/npr_rwfj_harvard_stress_poll.pdf

- 33.Ong AD, Cerrada C, Lee RA, et al. Stigma consciousness, racial microaggressions, and sleep disturbance among Asian Americans. Asian Am J Psychol 2017;8:72–81. 10.1037/aap0000062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson B, Knutsson A, Lindahl B. Is there an association between shift work and having a metabolic syndrome? results from a population based study of 27,485 people. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:747–52. 10.1136/oem.58.11.747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turek FW, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian clock mutant mice. Science 2005;308:1043–5. 10.1126/science.1108750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat 2005;4:287–91. 10.1002/pst.185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kieser M, Wassmer G. On the use of the upper confidence limit for the variance from a pilot sample for sample size determination. Biometrical Journal 1996;38:941–9. 10.1002/bimj.4710380806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Im E-O, Kim S, Xu S, et al. Issues in recruiting and retaining Asian American breast cancer survivors in a technology-based intervention study. Cancer Nurs 2020;43:E22–9. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . Process of translation and adaptation of instruments, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 40.National Library of Medicine . NIH CDE repository. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine, 2021. https://cde.nlm.nih.gov/cde/search [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suinn RM, Ahuna C, Khoo G. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity Acculturation scale: concurrent and factorial validation. Educ Psychol Meas 1992;52:1041–6. 10.1177/0013164492052004028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Im E-O, Kim S, Ji X, et al. Improving menopausal symptoms through promoting physical activity: a pilot web-based intervention study among Asian Americans. Menopause 2017;24:653–62. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang Y, Chiriboga DA. Living in a different world: Acculturative stress among Korean American elders. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2010;65B:14–21. 10.1093/geronb/gbp019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoo HC, Steger MF, Lee RM. Validation of the subtle and blatant racism scale for Asian American college students (SABR-A(2)). Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2010;16:323–34. 10.1037/a0018674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slavich GM, Shields GS. Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the stress and adversity inventory for adults (adult strain): an overview and initial validation. Psychosom Med 2018;80:17–27. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sturmbauer SC, Shields GS, Hetzel E-L, et al. The stress and adversity inventory for adults (adult strain) in German: an overview and initial validation. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cazassa MJ, Oliveira MdaS, Spahr CM, et al. The stress and adversity inventory for adults (adult strain) in Brazilian Portuguese: initial validation and links with executive function, sleep, and mental and physical health. Front Psychol 2019;10:3083. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banica I, Sandre A, Shields GS, et al. The error-related negativity (ERN) moderates the association between interpersonal stress and anxiety symptoms six months later. Int J Psychophysiol 2020;153:27–36. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith T, Johns-Wolfe E, Shields GS, et al. Associations between lifetime stress exposure and prenatal health behaviors. Stress Health 2020;36:384–95. 10.1002/smi.2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLoughlin E, Fletcher D, Slavich GM, et al. Cumulative lifetime stress exposure, depression, anxiety, and well-being in elite athletes: a mixed-method study. Psychol Sport Exerc 2021;52:101823. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harkness A, Behar-Zusman V, Safren SA. Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on Latino sexual minority men in a US HIV hot spot. AIDS Behav 2020;24:2017–23. 10.1007/s10461-020-02862-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System . Depression: a brief guide to the PROMIS© depression instruments 2019, 2019. Available: https://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures?task=Search.search

- 53.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System . Anxiety: a brief guide to the PROMIS© anxiety instruments 2019, 2019. Available: https://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures?task=Search.search

- 54.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, et al. Test-Retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:737–40. 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sohn SI, Kim DH, Lee MY, et al. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Sleep Breath 2012;16:803–12. 10.1007/s11325-011-0579-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rifas-Shiman SL, Willett WC, Lobb R, et al. PrimeScreen, a brief dietary screening tool: reproducibility and comparability with both a longer food frequency questionnaire and biomarkers. Public Health Nutr 2001;4:249–54. 10.1079/phn200061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun S, Lulla A, Sioda M, et al. Gut microbiota composition and blood pressure. Hypertension 2019;73:998–1006. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Human Microbiome Project Consortium . A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012;486:215–21. 10.1038/nature11209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Z, Hui PC, Hui M, et al. Impact of preservation method and 16S rRNA hypervariable region on gut microbiota profiling. mSystems 2019;4:e00271–18. 10.1128/mSystems.00271-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bukin YS, Galachyants YP, Morozov IV, et al. The effect of 16S rRNA region choice on bacterial community metabarcoding results. Sci Data 2019;6:190007. 10.1038/sdata.2019.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016;13:581–3. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Holmes SP. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. Isme J 2017;11:2639–43. 10.1038/ismej.2017.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 2011;12:R60. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:852–7. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bai J, Jhaney I, Daniel G, et al. Pilot study of vaginal microbiome using QIIME 2™ in women with gynecologic cancer before and after radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2019;46:E48–59. 10.1188/19.ONF.E48-E59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bai J, Jhaney I, Wells J. Developing a reproducible microbiome data analysis pipeline using the Amazon web services cloud for a cancer research group: proof-of-concept study. JMIR Med Inform 2019;7:e14667–e67. 10.2196/14667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aqua JK. Hiding behind a mask: perspectives from an Asian American epidemiologist. Epidemiology 2020;32:147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Czeisler Mark É, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1049. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dedoncker J, Vanderhasselt M-A, Ottaviani C, et al. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: the importance of the vagus nerve for biopsychosocial resilience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;125:1–10. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slavich GM. Social safety theory: a biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2020;16:265–95. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.