Abstract

A 63-year-old woman presented with headache, progressive somnolence, neurocognitive decline and urinary incontinence through a year. Medical history was unremarkable except for hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. Neurological examination was normal. Brain MRI showed findings typical for spontaneous intracranial hypotension (subdural fluid collection, pachymeningeal enhancement, brain sagging) and pituitary tumour. The patient’s complaints improved dramatically but temporarily after treatment with each of repeated targeted as well as non-targeted blood patches and a trial with continuous intrathecal saline infusion. Extensive work up including repeated MRI-scans, radioisotope cisternographies, CT and T2-weighted MR myelography could not localise the leakage, but showed minor root-cysts at three levels. Finally, lateral decubitus digital subtraction dynamic myelography with subsequent CT myelography identified a tiny dural venous fistula at the fourth thoracic level. After surgical venous ligation, the patient fully recovered. Awareness of spontaneous dural leaks and their heterogeneous clinical picture are important and demands an extensive workup.

Keywords: memory disorders, headache (including migraines), neuroimaging, pain (neurology)

Background

Spontaneous orthostatic headache with cognitive impairments and without a history of previous dural trauma can be a diagnostic pitfall. Patients may be misdiagnosed with chronic tension-type headache, chronic migraine or new daily persistent headache, depression, dementia, viral meningitis and malingering before being diagnosed with spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) and get the right treatment. It is crucial to suspect SIH and use relevant neuroradiological modalities to confirm the diagnosis in patients with orthostatic headache or cognitive dysfunction with coexisting headache symptoms.

SIH is categorised as a secondary headache, and was first described in 1938 by Schaltenbrand, a German neurologist. Since a study in 2002 documented that SIH commonly was misdiagnosed,1 this syndrome is increasingly reported, thanks to advancement in radiologic diagnostic techniques and greater awareness about SIH among healthcare professionals.2

A systemic review in USA published in 2006 reported the incidence of SIH is considered to be 5 per 100 000 persons per year and the peak incidence is around age 40 with a female to male ratio of 2:1.3

We report an atypical SIH case presenting with symptoms of behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and discuss clinical investigations, differential diagnoses and treatment, based on review of relevant literature.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old woman, recently retired from a full-time job and active participant in various hobby groups, presented with increasing fatigue, bilateral tinnitus, new daily persistent headache and neck stiffness through 3 months. The headache was dull, bilateral, of moderate intensity, worst in the afternoon and not orthostatic but aggravated with certain activities such as the Valsalva manoeuvre, bending forward, coughing and sneezing. She had no history of previous spinal procedures nor head/back trauma. Before admission to hospital, she had tried over-the-counter analgesics and massage without effect.

Medical history included well-controlled hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. Neurological examination was normal apart from cognitive dysfunction with apathia and latency.

Brain CT revealed bilateral subdural fluid collection and it was initially considered as chronic complication of an unknown previous trauma and watchful waiting begun, as there was no indication for surgical intervention.

Through the next 6 months, the patient was readmitted three times because of acroparesthesia, headache and worsening of cognitive functions, with affection of memory and increasing apathy. She gradually developed urinary incontinence, was somnolent and unable to perform daily activities including her leisure time activities and became progressively socially isolated. General neurological examination was still normal whereas formal neuropsychological consultation showed difficulties in concentration, memory and fine motor skills.

Investigations

Brain CT scanning is the most available imaging modality in emergency departments and can sometimes demonstrate features suggesting the SIH diagnosis; including subdural fluid collections, slit-shaped ventricles, tight basal cisterns, scant CSF over the cortex or increased tentorial enhancement.4

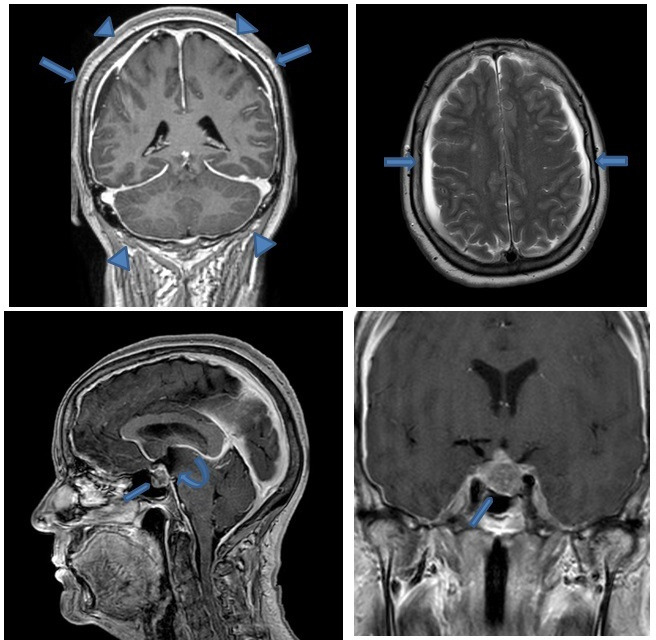

Brain MRI is the modality of choice in diagnosis confirmation of SIH, which in addition to the CT scan shows: bilateral subdural effusions, diffuse meninngeal enhancement, brain sagging, engorgement of cerebral venous sinuses, flattening of optic chiasm and increased anteroposterior diameter of the brainstem.4 Brain MRI in our patient showed all of the typical findings in SIH. Another finding was a 1.5 cm pituitary tumour (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brain MRI with contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence shows diffuse smooth pachymeningeal enhancement (arrowheads), bilateral small subdural effusions arrows), and brain sagging with narrowed prepontine cistern, downslope third ventricle (curved arrow) and cerebellar tonsils, small pontomesencephalic angle. Note also pituitary macroadenoma (pentagon).

After clinical and radiological confirmation of the SIH diagnosis, the challenge was to localise the exact site of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, with spine MRI and CT or MR myelography.

Spine MRI may identify extradural fluid collections or meningeal diverticula. However, in this case, spine MRI could not identify the leak.

MR myelography using T2-weighted sequences can be used to detect the level of CSF leaks.5 In our case, MR myelography showed a 4 mm root cyst in the right Th4–Th5 level as well as small perineural cysts on the left side on the level Th8/Th9 and Th9/Th10, but failed to identify the location of CSF leakage or any fluid collection around the spinal cord.

Spine CT may show degenerative changes, such as osteophytes and calcified disc protusions, which can directly tear the dura. Initial CT myelography and dynamic CT myelografi showed the small perineural cysts which was previously detected with MR of spine, but could not identify discogenic microspurs or extra dural fluid collections.

Radioisotope cisternography is the next step, when suspecting a CSF leak with a normal or non-diagnostic MRI. This procedure studies the dynamic flow of a radioisotope, which is injected intrathecally, with scanning at predetermined intervals, usually 24 or 48 hours.6

In our case, a 99m Technetium-99m diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (TC-DTPA) cisternography was performed and showed low pressure in the spinal fluid, compatible with intracranial hypotension, and early bladder activity which occurs in active leaks,4 but it could not reveal any leaks in the spinal canal or sinuses.

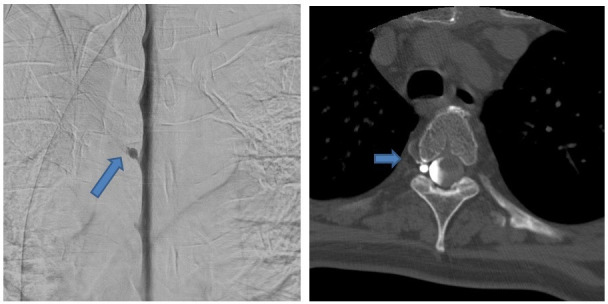

Finally, dynamic lateral decubitus digital subtraction myelography was decided to be performed. Left lateral decubitus myelography was negative, but right lateral decubitus myelography, performed 7 days later finally revealed a tiny CSF venous fistula at the right fourth thoracic level (figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Right-sided lateral decubitus digital subtraction myelography shows a CSF venous fistula around a perineural cyst on the level Th4/Th5 on the right. (B) Subsequent CT myelography on right lateral decubitus position confirms the CSF venous fistula. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Recently, a case report has emphasised the importance of suspecting a CSF venous fistula in SIH patients, particularly, when conventional neuroimaging failed to identify leakage site. Visualisation of the fistula requires dynamic positive pressure CT myelography with lateral decubitus positioning.7

Differential diagnosis

Headache attributed to SIH is usually, but not invariably orthostatic. When our patient initially presented with new daily persistent headache for several months, the orthostatic features had been present at onset, but were dissipated over time, and as the neurological examination was normal, the patient was initially diagnosed, and treated for tension-type headache without further workup. The patient had mentioned that headache worsens in the afternoon. Although this characteristic is also seen in tension-type headache, some patients suffering from SIH report, that headache severity increases in the afternoon as more time is spent upright.8 All headache patients should be asked about orthostatic nature of the headache at its onset, as this feature may become much less obvious over time.

As the patient’s headache worsened, and she developed increasing cognitive impairment, she was referred to our hospital. Initial workup with brain CT showing bilateral hygromas raised suspicion about chronic post-traumatic headache, which could also explain problems with concentration and short-term memory, but the patient did not report any head trauma in the past year.

As cognitive symptoms progressed, and the patient developed urinary incontinence, apathy and social withdrawal, an underlying dementia such as bvFTD was suspected. However, brain MRI showed no atrophy in the frontotemporal region but the characteristic findings of SIH.

Treatment

Some cases of SIH resolve with conservative treatment, which includes: bed rest, caffeine and oral hydration. The most common employed treatment for SIH is epidural blood patch (EBP), which can be targeted to CSF leak site or administered non targeted. In many cases, multiple EBPs are needed.9

In our case conservative treatment had limited effect. The patient was over a year treated with more than ten autologous lumbar EBP and three targeted thoracic EBP, each with immediate dramatic but short-lasting effect on both headache and cognitive symptoms. Initially EBP had an effect for up to 4 weeks but over time the duration of following EBPs’ effect was reduced to few hours.

Neuropsychological consultation at each hospital admission showed decline in patient’s concentration, memory and concrete thinking, which was reversed surprisingly to normal after each blood patch.

The pituitary tumour was regarded as an incidental finding at first, but as patient’s symptoms persisted despite treatment, and CSF leakage site was not found, the pituitary tumour and a following skull base defect was considered as the primary CSF leakage site. After direct questioning, the patient reported subjective symptom of rhinorrhea for a long time, although it was not possible to verify clinically.

Hormonal analyses revealed no endocrinopathy and neuro-ophthalmological examination including perimetry was also normal. After consultation with neurosurgeons, she was referred to pituitary tumour surgery, as the most probable site of CSF leak due to additional subjective symptoms of rhinorrhea. Pathological examination confirmed benign pituitary tumour. The patient was free of symptoms for 14 days after pituitary adenoma resection surgery, and then she was readmitted. This time the headache was only present when coughing, but the patient’s family was concerned about the patient’s progressive somnolence, indifference and apathy.

As the headache and cognitive dysfunction still hindered the patient from daily activities, it was decided to try continuous intrathecal saline infusion, as suggested by some case reports,10 11 but again without persistent effect.

After repeated neuroradiological investigations with brain and spine MRI, finally, right lateral decubitus dynamic digital subtraction myelography with subsequent CT myelography was performed and revealed the leakage site; a CSF venous fistula at the fourth thoracic level.

The patient was now referred for spinal surgery and the venous fistula was ligated.

Outcome and follow-up

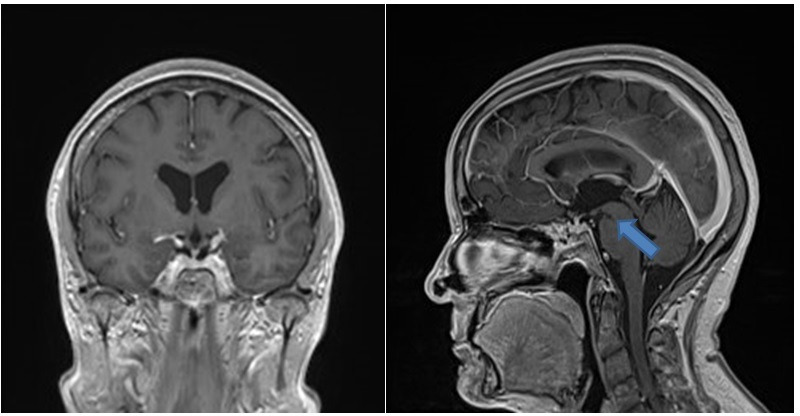

At 3 months follow-up, the patient was fully recovered. She reported just mild symptoms and was satisfied with the treatment. Control MRC after 3 months showed no hygromas, no dural enhancement and no brain sagging and reduced anteroposterior diameter of the brainstem (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Control brain MRI with contrast enhanced T1-weighted sequence after surgical treatment of the CSF venous fistula shows nearly complete resolution of the signs of SIH. There is only smaller pontomesencephalic angle. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Discussion

The aetiology of spontaneous CSF leaks is largely unknown, but considered to be a combination of weakness in thecal sac and a minor trauma. Possible aetiologies are listed in Box 1.2 4

Box 1. Typical detectable etiologies of spontaneous CSF leak2 4 18.

1. Dural tears due to

Minor/trivial trauma

A sudden twist, stretch or sneeze

Fall

Sexual intercourse or orgasm

Sports activity

Degenerative disc disease

Osseous spurs or microspurs

2. Weakness in thecal sac

Defects of dura

Epidural/perineural cysts

Meningeal diverticula

Connective tissue disorders

Marfan syndrome

Autosomal dominant ploy cystic kidney disease

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type II

Isolated skeletal features of Marfan syndrome

Isolated joint hypermobility

Joint hypermobility with facial thining

Spontaneous retinal detachment

3. CSF venous fistula

The patient presented in our case could not recall any traumas, although it was a very likely diagnosis with the bilateral subdural haematomas on brain CT. However, in the prospective cohort study on chronic subdural haematoma in non-geriatric patients by Beck et al, CSF leaks were the underlying cause in 25.9% of patients.12

Dobrocky et al13 suggested a new brain MRI scoring system based on six typical findings in SIH, where pachymeningeal enhancement, and effacement of supracellar sinus is considered a major sign (two points) and subdural fluid collection, effacement of the prepontine cistern of 5.0 mm or less, and mamillopontine distance of 6.5 mm or less are considered minor (one point). Furthermore, they classify patients in three groups based on their total brain MRI scores (2 points or fewer, 3–4 points and 5 points or more, on a scale of 9 points), claiming detecting a CSF leakage site is more probable with higher scores. Based on this scoring system, our patient can be classified with a high probability of having a spinal CSF leak.

Dobrocky et al13 have also reported that SIH patients with confirmed spinal CSF leak tend to have a pituitary gland superior border with convex shape on brain MRI compared with the control group (respectively, 63% and 8%). However, MRI of the brain in our patient showed additionally to typical SIH findings a pituitary tumour, which was confirmed to be a benign adenoma.

Nevertheless, pituitary hyperplasia is a common cofinding in SIH, and there are reports of misdiagnosing it as pituitary adenoma.14 There is only one case report of a patient with SIH and pituitary adenoma, but here no myelography was performed as the patient refused further investigation and therapy.15 A review of 29 articles presenting CSF leakage in the setting of pituitary adenoma, published in 2012, reported CSF leakage in 27% of patients, but did not report SIH in any of the patients.16 The presumed mechanism of CSF leaks due to pituitary adenomas may be due to adenoma invasion into the sella, which does not have clinical significance at first, but later an infarction or haemorrhage in the tumour can result in shrinkage and subsequently provide a conduit for CSF leak.

It is considered that the location of CSF leak is almost exclusively spinal. A study of 273 patients with SIH in 2012, could not show any association between SIH and skull base leaks.17 Schievink et al published a systematic review in 2016 and classified SIH in four categories based on CSF leak types (table 1).18 After an extensive and challenging workup in our patient, we finally identified a type 3, CSF venous fistula.

Table 1.

Classification of spinal CSF leaks22

| Type 1 | Dural tear (a. ventral, b. dorsolateral) |

| Type 2 | Meningeal diverticulum (a.simple, b.complex) |

| Type 3 | CSF-Venous fistula |

| Type 4 | Indeterminate/unknown |

Pathophysiology of SIH is long considered to be low CSF pressure, but studies have showed that the majority of patient with SIH have a CSF opening pressure within the normal range, and the pathophysiology of SIH may rather be reduced intracranial CSF volume rather than CSF hypotension.19

The cardinal manifestation of SIH is orthostatic headaches, that is, the headache is aggravated in standing position and by Valsalva type manoeuvres. During the course of illness, orthostatic headaches may be replaced by a more chronic unspecific daily headache. Other common symptoms include: dizziness, nausea and vomiting, visual blurring, change in hearing (eg, hyperacusis, echoing, tinnitus), diplopia and neck pain or stiffness.4 Less frequent or rare manifestations associated with SIH include: movement disorders (parkinsonism, tremor, chorea and dystonia), ataxia, galactorrhea and hyperprolactinaemia, quadriparesis, frontotemporal dementia, decreased level of consciousness, stupor and coma.2 20 The presentation of SIH with clinical symptoms like frontotemporal dementia, as in our case, is very rare.20–23 Wicklund et al in a case series in 2011 reported eight SIH patients with presentations mimicking bvFTD, and termed the condition frontotemporal brain sagging syndrome.20 Interestingly five of these patient had underwent Brain positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), which showed relative hypometabolism of the frontal or temporal lobes, but no frontotemporal atrofi.

SIH patients suffering from atypical clinical presentations including those mimicking bvFTD seem to have a more chronic syndrome presenting with severe brain sagging, lower rates of clinical response, frequent relapses, less often demonstrated CSF leak on spinal imaging, and more often undergo surgery compared with classic SIH patients.21 22

EBP is the mainstay of treatment for SIH.2 It is assumed that EBP works through volume replacement initially, and sealing a dural defect within 3 weeks by fibrin deposition and scar formation. However, approximately 50% of SIH patients require more than one EBP treatment.24 In an interesting case report, a patient with frontotemporal cognitive dysfunction during 6 years come to reverse his symptoms by an accidentally fall with contusion injury subsequently resulting in an autoblood patch.24

In patients where repeated lumbar and targeted epidural patchings are unsuccessful, other treatment options include epidural fibrin glue, continuous intrathecal saline infusion and finally surgical repair which, however, demands identification of the site of the dural leak.4

Learning points.

The most common initial clinical manifestation of spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) is orthostatic headache, that is, headache that worsens soon after sitting/standing upright and improves in recumbency. The orthostatic nature of the headache at its onset may dissipate over time.

Evidence of SIH is needed for diagnosis confirmation, and require brain MRI with gadolinium and intensive search for a CSF leak on spine MRI and/or CT/MR myelography.

The five characteristic findings in brain MRI of SIH patients are: subdural fluid collections, enhancement of the pachymeninges, engorgement of venous structures, pituitary hyperaemia and sagging of the brain.

Based on severity of patient’s symptoms treatment can vary from conservative treatment (bed rest and caffeine intake), epidural blood patch (mainstay of treatment) and continuous intrathecal saline infusion or surgery if the leak can be verified.

It is crucial to consider SIH as a differential diagnosis, when evaluating patients with cognitive impairments especially in copresence of headache, because it is a potentially reversible and fully treatable condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank our clinical coworkers Anna Stroemmen, MD, PhD, Maiken Tibaek, MD, PhD, and Sofia Santos MD, for very dedicated work and persistent support during the patient course.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors have all contributed to the case SSG contributed with planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, and acquisition of data. ES contributed with acquisition of imaging data and interpretation of imaging data and the report. BKR contributed with planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, and acquisition of data. RHJ contributed with planning, reporting, conception, acquisition of data analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Schievink WI. Misdiagnosis of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1713. 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kranz PG, Malinzak MD, Amrhein TJ, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2017;21:37. 10.1007/s11916-017-0639-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schievink WI, Maya MM, Moser F, et al. Frequency of spontaneous intracranial hypotension in the emergency department. J Headache Pain 2007;8:325–8. 10.1007/s10194-007-0421-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA 2006;295:2286–96. 10.1001/jama.295.19.2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai P-H, Fuh J-L, Lirng J-F, et al. Heavily T2-weighted Mr myelography in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension: a case-control study. Cephalalgia 2007;27:929–34. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokri B. Radioisotope cisternography in spontaneous CSF leaks: interpretations and misinterpretations. Headache 2014;54:1358–68. 10.1111/head.12421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah VN, Dillon WP. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension with brain sagging attributable to a cerebrospinal Fluid–Venous fistula. JAMA Neurol 2020;58:948–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leep Hunderfund AN, Mokri B. Second-half-of-the-day headache as a manifestation of spontaneous CSF leak. J Neurol 2012;259:306–10. 10.1007/s00415-011-6181-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schievink WI, Deline CR. Headache secondary to intracranial hypotension topical collection on secondary headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2014;18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam G, Mehta V, Zada G. Spontaneous and medically induced cerebrospinal fluid leakage in the setting of pituitary adenomas: review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2012;32:E2. 10.3171/2012.4.FOCUS1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pleasure SJ, Abosch A, Friedman J, et al. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension resulting in stupor caused by diencephalic compression. Neurology 1998;50:1854–7. 10.1212/WNL.50.6.1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck J, Gralla J, Fung C, et al. Spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak as the cause of chronic subdural hematomas in nongeriatric patients. J Neurosurg 2014;121:1380–7. 10.3171/2014.6.JNS14550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobrocky T, Grunder L, Breiding PS, et al. Assessing spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks in spontaneous intracranial hypotension with a scoring system based on brain magnetic resonance imaging findings. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:580–7. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luna J, Khanna I, Cook FJ, et al. Sagging brain masquerading as a pituitary adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3043. 10.1210/jc.2014-1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firat AK, Karakas HM, Firat Y, et al. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension with pituitary adenoma. J Headache Pain 2006;7:47–50. 10.1007/s10194-006-0269-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binder DK, Dillon WP, Fishman RA, et al. Intrathecal saline infusion in the treatment of obtundation associated with spontaneous intracranial hypotension: technical case report. Neurosurgery 2002;51:830–7. 10.1097/00006123-200209000-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schievink WI, Schwartz MS, Maya MM, et al. Lack of causal association between spontaneous intracranial hypotension and cranial cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Neurosurg 2012;116:749–54. 10.3171/2011.12.JNS111474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schievink WI, Maya MM, Jean-Pierre S, et al. A classification system of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks. Neurology 2016;87:673–9. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kranz PG, Tanpitukpongse TP, Choudhury KR. Imaging signs in spontaneous intracranial hypotension: prevalence and relationship to CSF pressure. in: American Journal of Neuroradiology. American Society of Neuroradiology 2016:1374–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wicklund MR, Mokri B, Drubach DA, et al. Frontotemporal brain sagging syndrome: an SIH-like presentation mimicking FTD. Neurology 2011;76:1377–82. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capizzano AA, Lai L, Kim J, et al. Atypical presentations of intracranial hypotension: comparison with classic spontaneous intracranial hypotension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:1256–61. 10.3174/ajnr.A4706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schievink WI, Maya MM, Barnard ZR, et al. Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia as a serious complication of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Oper Neurosurg 2018;15:505–15. 10.1093/ons/opy029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sencakova D, Mokri B, McClelland RL. The efficacy of epidural blood patch in spontaneous CSF leaks. Neurology 2001;57:1921–3. 10.1212/WNL.57.10.1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slattery CF, Malone IB, Clegg SL, et al. Reversible frontotemporal brain sagging syndrome. Neurology 2015;85:833. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]