To the Editor:

Sofosbuvir is considered as a paradigm shift in treating hepatitis C viral infection (HCV) [1]. Patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) usually receive both anti-HCV and antiretroviral therapy [2]. Emerging evidence, recently reported by this and other journals, has linked sofosbuvir-containing regimens to liver or kidney toxicity when co-administered with anti-HIV drugs [2–6]. Interestingly, sofosbuvir and some anti-HIV drugs such as tenofovir disoproxil contain ester and/or amide bonds. These chemical bonds are hydrolyzed by carboxylesterases. In humans, there are two major carboxylesterases: CES1 and CES2 [7].

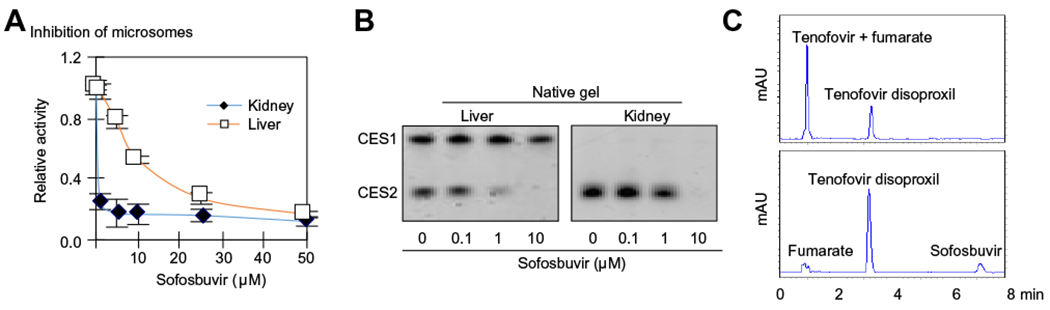

This study reports that sofosbuvir is a potent and covalent CES2 inhibitor. Human liver or kidney microsomes were preincubated with sofosbuvir at 0–50 μM. The colorimetric substrate p-nitrophenylacetate (PNPA) was subsequently added. The hydrolysis of PNPA was monitored with a microplate-reader by an increase in the absorbance at 400 nm [8]. The liver microsomes were pooled from 20 donors including 12 males and 8 females. The kidney microsomes were pooled from 12 including 7 males and 5 females. As shown in Fig. 1A, sofosbuvir potently inhibited the hydrolysis by both liver and kidney microsomes. The inhibition of kidney hydrolysis was more profound. At 5 μM, sofosbuvir inhibited kidney hydrolysis by 82%.

Fig. 1. Inhibition of CES2 by sofosbuvir.

(A) Inhibition of microsomal hydrolysis by sofosbuvir microsomes for human liver (0.25 μg/per well) or kidney (1 μg/per well) were incubated with sofosbuvir for 120 min at 0–50 μM in a total volume of 90 μl and then 10 μl of p-nitrophenylacetate (PNPA) was added at a final concentration of 1 mM. The hydrolysis of PNPA was monitored with a microplate-reader from an increase in the absorbance at 400 nm. (B) Native-gel electrophoresis stained for hydrolytic activity microsomes (0.25 μg) were incubated with sofosbuvir at 0–10 μM and subjected to native gel electrophoresis and stained for esterase activity with 4-methylumbelliferylacetate. (C) Inhibited hydrolysis of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate lysates from CES2 transfected cells were pre-incubated with sofosbuvir at 20 μM or the reaction buffer at 37 °C for 120 min, followed by addition of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at a final concentration of 20 μM. The incubations lasted for an additional 30 min and were then mixed with acetonitrile at a final concentration of 66%. The reactions were centrifuged to remove the proteins and the supernatants were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (Hitachi-300). (This figure appears in colour on the web.)

The kidney predominantly expresses CES2 but not CES1 [7], and the profound inhibition of the kidney hydrolysis suggested that CES2 was a sensitive target of sofosbuvir. It has been reported that sofosbuvir was a CES1 substrate [9]. These observations pointed to the possibility that sofosbuvir inhibited CES2 through a mechanism other than competitive inhibition. We next tested whether covalent modification was involved in the inhibition. Liver and kidney microsomes were incubated with sofosbuvir at 0–10 μM. The reaction mixtures were subjected to electrophoresis (native gel) to remove unbound sofosbuvir. The gel was then stained for carboxylesterase activity [8]. As expected, this method detected two activity bands in liver microsomes (Fig. 1B). The activity band with the slower mobility corresponded to CES1 and was not affected by sofosbuvir except at 10 μM (~15% inhibition). In contrast, the activity band with the faster mobility (i.e., CES2) was drastically reduced by 1 μM sofosbuvir and completely eliminated by 10 μM (Fig. 1B). Similar observations were made on CES2 in kidney microsomes (i.e., CES2).

To shed light on the significance of the inhibition in relation to interactions with anti-HIV drugs, lysates from CES2-transfected cells were pre-incubated with sofosbuvir or solvent and tested for the hydrolysis of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (fumaric acid salt), a widely used anti-HIV agent that has been implicated in organ toxicity with sofosbuvir [2–6]. The reactions were precipitated with acetonitrile and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography. As shown in Fig. 1C (top), incubation with CES2 caused ~70% conversion of tenofovir disoproxil into its hydrolytic metabolite: tenofovir. However, the hydrolytic conversion was inhibited by sofosbuvir. The incubations were performed at pharmacological concentrations in the liver for both tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and sofosbuvir [5].

Sofosbuvir is a substrate of drug transporters [10]. Therefore, it has been assumed that sofosbuvir interacts with drugs that share these transporters. In this study, we have demonstrated that sofosbuvir is also a potent and covalent CES2 inhibitor, providing a novel mechanism for interactions with drugs that are CES2 substrates such as tenofovir. Indeed, it has been reported that sofosbuvir-containing regimens increased the blood exposure of tenofovir by as much as 98% [10]. The toxicological consequences of the hydrolytic interactions, on the other hand, depend on the relative toxicity between a parent drug and its hydrolytic metabolite. As for tenofovir disoproxil, the inhibition of its hydrolysis may decrease the toxicity if its hydrolytic metabolite is more toxic than the parent drug. In this case, organ-based hydrolysis may come into play. For example, sofosbuvir at a certain dose inhibits liver and kidney CES2 with the liver enzyme being inhibited to a greater extent. The blood concentration of tenofovir disoproxil will elevate, the kidney hydrolysis will increase, and kidney toxicity might be more evident. Alternatively, predominant inhibition of intestinal CES2 by sofosbuvir may facilitate the absorption of tenofovir disoproxil, leading to elevated levels of this anti-HIV drug in the liver with increased risk of hepatic toxicity upon hydrolysis.

Another major variable is the overall activity of drug transporters for a parent drug and its metabolite. Hydrolysis of an ester, for example, produces a carboxylic acid species [7]. This molecular species is negatively charged at physiological conditions and effluxed out by transporters. As a result, cells with high level expression of relevant transporters may not exhibit severe toxicity. Therefore, the toxicological consequences of the hydrolytic interactions depend on the interplay between CES2 and drug transporters, and the interplay may vary depending on an organ. In addition, sofosbuvir is commonly used together with other anti-HCV drugs, particularly with the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir [5]. It remains to be determined whether ledipasvir contributed to the observed toxicity [2–5]. Nevertheless, clinical trials are required to fully assess the pharmacological and toxicological significance of the potent and covalent inhibition of CES2 by sofosbuvir. The authors have been actively pursuing this possibility.

Financial support

This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM61988, R01EB018748 and R15AT007705.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

References

- [1].deLemos AS, Chung RT. Hepatitis C treatment: an incipient therapeutic revolution. Trends Mol Med 2014;20:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Poizot-Martin I, Naqvi A, Obry-Roguet V, Valantin MA, Cuzin L, Billaud E, et al. Hepada’AIDS Study Group. Potential for drug-drug interactions between antiretrovirals and HCV direct acting antivirals in a large cohort of HIV/HCV coinfected patients. PLoS One 2015;10 e0141164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marchan-Lopez A, Dominguez-Dominguez L, Kessler-Saiz P,Jarrin-Estupiñan ME. Liver failure in human immunodeficiency virus – Hepatitis C virus coinfection treated with sofosbuvir, ledipasvir and antiretroviral therapy. J Hepatol 2016;64:752–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wanchoo R, Thakkar J, Schwartz D, Jhaveri KD. Harvoni (ledipasvir with sofosbuvir)-induced renal injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:148–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bunnell KL, Vibhakar S, Glowacki RC, Gallagher MA, Osei AM, Huhn G. Nephrotoxicity associated with concomitant use of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and tenofovir in a patient with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36:e148–e153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tseng A, Wong DK. Hepatotoxicity and potential drug interaction with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in HIV/HCV infected patients. J Hepatol 2016;65:651–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dyson JK, Hutchinson J, Harrison L, Rotimi O, Tiniakos D, Foster GR, et al. Liver toxicity associated with sofosbuvir, an NS5A inhibitor and ribavirin use. J Hepatol 2016;64:234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xiao D, Shi D, Yang D, Barthel B, Koch TH, Yan B. Carboxylesterase-2 is a highly sensitive target of the antiobesity agent orlistat with profound implications in the activation of anticancer prodrugs. Biochem Pharmacol 2013;85:439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Murakami E, Tolstykh T, Bao H, Niu C, Steuer HM, Bao D, et al. Mechanism of activation of PSI-7851 and its diastereoisomer PSI-7977. J Biol Chem 2010;285:34337–34347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].DATA SHEET HARVONI at www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/h/HarvoniTab.PDF.