Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES:

Medicare has become an increasingly complex program to navigate with numerous choices available to beneficiaries with important implications for their financial exposure and access to care. Although research has identified poor health literacy as a barrier to understanding Medicare, little information is available on the experience of individuals with hearing loss. This study examined how hearing loss impacts Medicare beneficiaries in understanding the program, their ability to compare and review plan options, and their satisfaction with available information.

DESIGN:

Cross-sectional analysis using multivariate ordinal logistic regression.

SETTING:

Nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States (Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey [MCBS]) 2017.

PARTICIPANTS:

A total of 10,510 Medicare beneficiaries were analyzed, representing 50,084,169 beneficiaries with survey weights applied.

MEASUREMENTS:

The primary outcome was difficulty understanding Medicare, determined by this MCBS question: “Overall, how easy or difficult do you think the Medicare program is to understand?” The predictor of interest was self-reported hearing loss measured categorically as no trouble, a little trouble, and a lot of trouble hearing. Covariates included age, sex, race, educational attainment, household income relative to the federal poverty level, enrollment in either traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage, dementia diagnosis, trouble with vision, and number of chronic conditions.

RESULTS:

Medicare beneficiaries with a little or a lot of trouble hearing had 18% (95% confidence interval [CI] odds ratio [OR] = 1.10–1.27) and 25% (95% CI OR = 1.07–1.47) increased odds of reporting greater difficulty with understanding Medicare, respectively, compared with those with no hearing trouble. About one in five Medicare beneficiaries with hearing loss identified that their hearing made it difficult to find Medicare information.

CONCLUSION:

The existing tools to support Medicare beneficiaries’ understanding and navigation of the program must evolve to meet the needs of those with hearing loss, a highly prevalent condition among Medicare beneficiaries.

Keywords: hearing loss, Medicare, health literacy

It has long been acknowledged that Medicare is a complex program.1 This complexity is related to both its structure and content. Although the structure continues to become more complex, efforts are ongoing to improve beneficiaries’ understanding of the program and their options.2 These efforts aim to address concerns of low health literacy among older adults3 by focusing on using simplified language across multiple mediums and stressing the need to be linguistically and culturally competent.4 Left out of the conversation to improve the understanding of the Medicare program are the barriers related to hearing loss, a condition experienced by two-thirds of Medicare beneficiaries aged 70 and older.5 This study examined the association between self-reported hearing loss and understanding Medicare, the availability of information, and satisfaction with the information available.

Medicare beneficiaries are confronted annually with multiple options regarding their health insurance. For those in the traditional Medicare program, beneficiaries have the choice of purchasing Medigap supplementary insurance plans. Most states offer 10 different types of Medigap plans, all with different levels of financial protection (i.e., deductibles and copayments). For beneficiaries who choose to be in Medicare Advantage (MA), the average number of plans available to choose from in 2019 was 24; some beneficiaries had as many as 50 choices of plans.6 For coverage of prescription drugs in 2019, those in traditional Medicare had, on average, 27 different plans to choose from, whereas in MA plans, the average number of prescription drug plans available in a county was 21 (among the 90% of MA plans offering prescription drug benefits).7 And finally, beneficiaries are also having to navigate alternatives for services that are not covered by Medicare including dental, vision, hearing, and long-term services and supports. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have long endeavored to support beneficiaries in making these decisions through multiple mediums including the Medicare and You book, 1-800-MEDICARE, and www.medicare.gov, and closed captioned YouTube videos.

To make informed decisions regarding plan choices requires both knowledge and understanding of a complex health vocabulary (e.g., premiums, deductibles, co-insurance, copayments, out-of-pocket limits, drug formularies, provider networks) as well as an accurate assessment of health needs and risks. This knowledge and understanding are often referred to as health literacy. A 2018 workshop on health literacy3 hosted by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) defined health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”8 Many barriers to health literacy have been identified including individual factors such as age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, income, and cognitive impairment.4,9 Despite the numerous reports on health literacy among older adults highlighting the possible impact of hearing loss on health literacy, research is lacking on the association between hearing loss and health literacy.3,9,10

This lack of research may be partly explained by the focus on measuring health literacy by some of the skills required to understand, such as numeracy and literacy,11,12 rather than the outcome of obtaining, processing, and understanding health information. The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) that conducts a nationally representative study of health literacy recognizes that it misses an important part of health literacy in its own tool. “Another aspect of health literacy is oral communication. … However, NAAL is not designed to assess the skills associated with listening and speaking because of the costs and difficulty of measuring them.”12 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently introduced three screening questions to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System that aim to capture three components of health literacy: finding information, understanding oral information, and understanding written information.13

Hearing loss may affect health literacy both in the way Medicare beneficiaries obtain the information, as well as how that information can be processed and understood. Hearing loss limits the ability to access auditory information that affects communication both in person and via tele-communications. Importantly, the encoding of auditory information for processing is the first step in communication, and poor access to auditory information may exacerbate health literacy issues stemming from other factors mentioned earlier such as education, language, and culture. Moreover, hearing loss is associated with cognitive impairment that could impact the processing of health information.14,15 Hearing loss overextends cognitive resources as the brain attempts to decode poor auditory signals and contributes to increased fatigue from continuous listening effort. Notably, research shows the association of hearing and cognitive processing is evident even on nonauditory cognition tasks that may reflect the cumulative impact of hearing loss on the brain over time.16

Identifying hearing loss as a barrier to understanding the Medicare program could provide an opportunity for future CMS policy to improve health literacy and access to information. A systematic review of studies evaluating the impact of low health literacy on health outcomes has shown low health literacy to be associated with more hospitalizations and emergency department visits, less use of preventive care, poor overall health status, and higher mortality rates.17 The objective of this study to examine how hearing loss impacts Medicare beneficiaries’ understanding of the program, ability to compare and review plan options, and satisfaction with available information.

METHODS

Data Source and Analytic Sample

Using the 2017 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries, we examined self-reported understanding of the Medicare program across different characteristics associated with health literacy. In 2017, the MCBS surveyed 11,401 Medicare beneficiaries regarding their understanding of Medicare. Individuals were excluded from this analysis for the following reasons: if they were deaf (n = 22), if they did not answer the primary outcome of understanding Medicare (n = 450), and if they were living in a facility or were not continuously enrolled in Medicare in 2017 (n = 419). The final sample was 10,510 Medicare individuals, representing 50,084,169 continuously enrolled beneficiaries, not residing in a facility with survey weights applied. These survey weights account for the sampling design in the MCBS including the oversampling of Hispanics and those aged 85 years and older, as well as nonresponse from the initial sample.18

Measures

The primary outcome of interest of this study was difficulty understanding Medicare, determined by this MCBS question: “Overall, how easy or difficult do you think the Medicare program is to understand?” Response options including “very easy,” “somewhat easy,” “somewhat difficult,” and “very difficult.” We also explored secondary outcomes that included additional health literacy questions regarding the availability of information and the ability of respondents to compare and review options, as well as information-seeking behaviors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomesa

| Question | Responses |

|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |

| “Overall, how easy or difficult do you think the Medicare program is to understand?” | -Very easy -Somewhat easy -Somewhat difficult -Very difficult |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| “How much do you think you know about the Medicare program?” | -Just about everything you need to know -Most of what you need to know -Some of what you need to know -A little of what you need to know -Almost none of what you need to know |

| “How easy of difficult would you say it is for you to review and compare your Medicare coverage options?” | -Very easy -Somewhat easy -Somewhat difficult -Very difficult |

| “How often do you review or compare your Medicare coverage options?” | -At least once every year -Once every few years -Rarely -Never |

| “I have the information I need to make an informed comparison among different health insurance choices.” | -Completely agree -Somewhat agree -Somewhat disagree -Completely disagree |

| “How satisfied are you in general with the availability of information about the Medicare program when you need it?” | -Very satisfied -Satisfied -Dissatisfied -Very dissatisfied |

| “Have you ever visited or ever accessed the official website for Medicare information, www.medicare.gov?” | -Yes -No |

| “Have you ever called 1-800-MEDICARE to get information about Medicare?” | -Yes -No |

From Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2017.

The predictor of interest for our study was self-reported hearing loss measured categorically as no trouble, a little trouble, and a lot of trouble hearing. Our covariate selection was informed through the health literacy literature.3,9,19,20 We included the following covariates in our analytic models: age, sex, race, educational attainment, household income relative to the federal poverty level (FPL), enrollment in either traditional Medicare or MA, dementia diagnosis, vision impairment, and number of chronic conditions.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive analytic methods to present the difficulties experienced across different subpopulations within Medicare to understand the program. In the MCBS there is a question targeted to those who self-reported either a little or a lot of trouble hearing that queried, “How much trouble do you have finding out things you need to know about Medicare because of your difficulty hearing?”

We report the findings of this question in our descriptive analyses. However, because this question is only asked of the subpopulation reporting hearing difficulty, we used the broader question (primary outcome of interest) to evaluate factors associated with difficulty understanding Medicare in the multivariate regressions.

Most of the primary and secondary outcomes of interest are ordinal categorical responses (e.g., very easy, somewhat easy, somewhat difficult, very difficult). In these instances, we used multivariate ordinal logistic regression to determine whether self-reported trouble hearing was associated with greater odds of the outcome. Two secondary outcomes were binary (yes/no) responses, and we therefore used multivariate logistic regression to assess those associations. All analyses used survey weights to account for MCBS survey design.

We conducted sensitivity analyses that stratified the population by those who did and did not call 1-800-MEDICARE for information, as well as by those who did and did not visit www.medicare.gov for more information. These sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore whether the association between hearing loss and understanding Medicare differed across those who sought out information and those who did not.

RESULTS

Descriptive Characteristics

Almost one-third of Medicare beneficiaries reported that Medicare was difficult to understand (25% somewhat difficult and 7% very difficult). As shown in Table 2, Medicare beneficiaries who reported that Medicare was somewhat difficult or very difficult to understand were more likely to be younger, Hispanic, have less than a high school education, and have lower household incomes relative to the FPL. They were also more likely to have a little or a lot of vision trouble, and they had a higher number of chronic conditions. Individuals reporting that Medicare was very difficult to understand were more likely to have a little (42%) or a lot of trouble hearing (7%), compared with those who said Medicare was very easy to understand (37% reported a little trouble hearing and 4% a lot of trouble hearing).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries by Ease of Understanding Medicarea

| How easy is Medicare to understand? |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very easy | Somewhat easy | Somewhat difficult | Very difficult | |

| Sample, unweighted | 2,531 | 4,817 | 2,454 | 708 |

| Population count, weighted | 11,399,731 | 22,590,973 | 12,646,791 | 3,446,673 |

| Population distribution, weighted | 23% | 45% | 25% | 7% |

| Age in 2017, y | Column percentages | |||

| <65 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 23 |

| 65–74 | 47 | 49 | 50 | 46 |

| 75–84 | 29 | 26 | 25 | 25 |

| 85+ | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48 | 46 | 45 | 43 |

| Female | 52 | 54 | 55 | 57 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 80 | 82 | 83 | 80 |

| Black | 13 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Other | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 15 | 15 | 16 | 24 |

| High school graduate | 50 | 51 | 48 | 47 |

| Completed college | 35 | 33 | 36 | 29 |

| Household income relative to federal poverty threshold, % | ||||

| <100 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 21 |

| 100–149 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 150–199 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| 200–399 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 24 |

| 400+ | 36 | 35 | 33 | 28 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Traditional Medicare | 62 | 66 | 67 | 64 |

| Medicare advantage | 38 | 34 | 33 | 36 |

| Dementia diagnosis | ||||

| No | 97 | 96 | 96 | 95 |

| Yes | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Hearing trouble | ||||

| No trouble | 58 | 56 | 51 | 51 |

| A little trouble | 37 | 39 | 43 | 42 |

| A lot of trouble | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Vision trouble | ||||

| No trouble | 71 | 66 | 59 | 53 |

| A little trouble | 26 | 31 | 36 | 38 |

| A lot of trouble | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| No. of chronic conditions | ||||

| None | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| 1–2 | 42 | 41 | 36 | 39 |

| 3–5 | 40 | 41 | 44 | 42 |

| ≥6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 12 |

From authors’ analysis of data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2017.

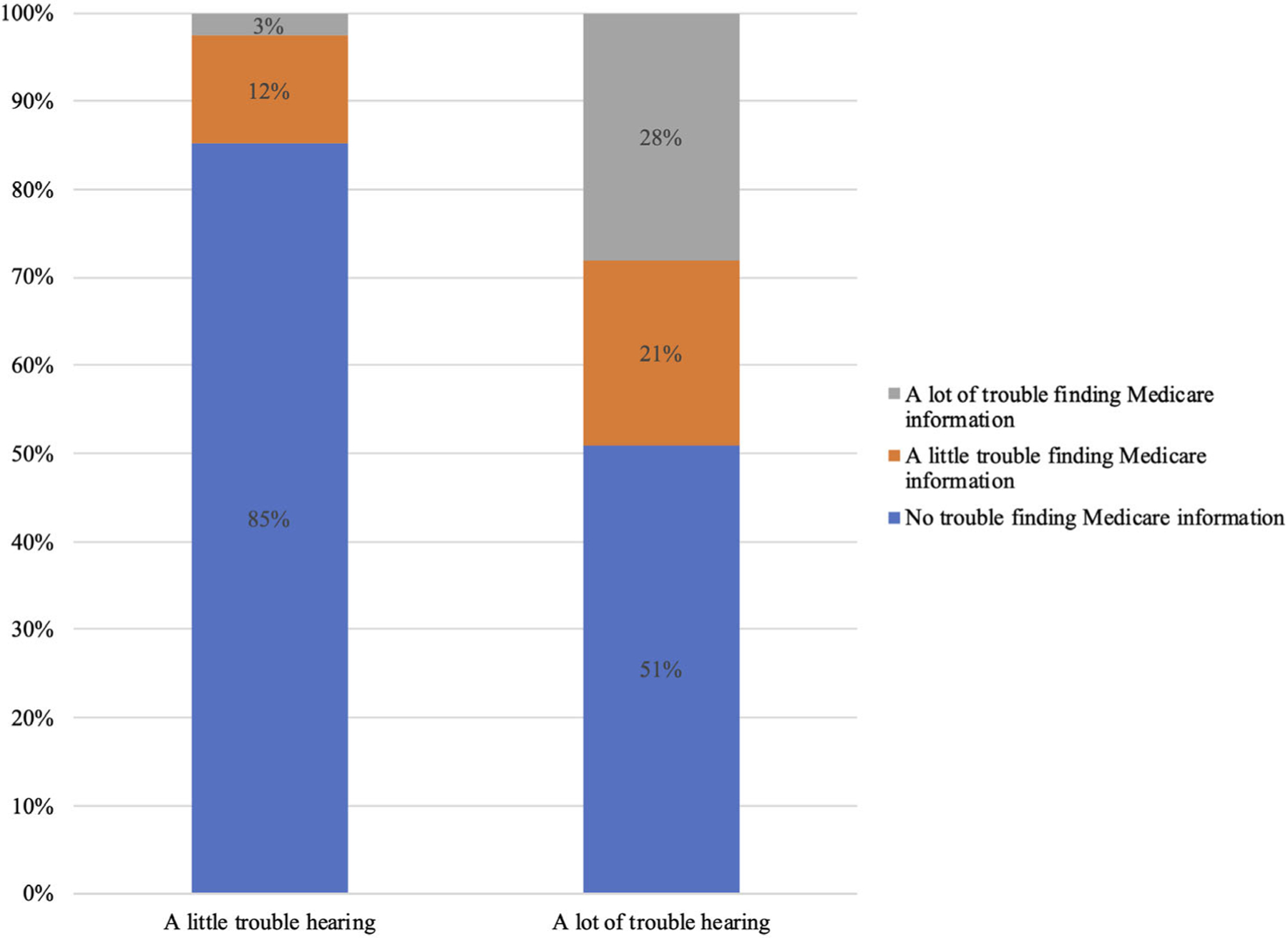

When asked specifically whether they had trouble finding Medicare information because of their hearing loss, almost one-half (49%) of those with a lot of difficulty hearing responded in the affirmative (Figure 1). Among those with a lot of difficulty hearing, 21% reported that they had a little trouble, and 28% reported they had a lot of trouble finding Medicare information because of their hearing. For those with a little trouble hearing, 12% and 3% said they had a little trouble and a lot of trouble finding Medicare information because of their hearing, respectively. A total of 18% of Medicare beneficiaries with any trouble hearing reported that they had at least a little trouble finding Medicare information because of it (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with hearing loss who report difficulty finding Medicare information due to hearing. Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2017.

Hearing Loss and Understanding Medicare

When controlling for covariates associated with health literacy, those who self-reported having a little trouble hearing and a lot of trouble hearing were at 18% (95% confidence interval [CI] odds ratio [OR] = 1.10–1.27) and 25% (95% CI OR = 1.07–1.47) higher odds, respectively, of reporting greater difficulty understanding Medicare (Table 3). Similarly, among the secondary outcomes, Medicare beneficiaries who reported a little and a lot of trouble hearing had 15% (95% CI OR = 1.08–1.23) and 16% (95% CI OR = 1.01–1.34) greater odds, respectively, of reporting that they felt they did not know much about Medicare compared with those with no trouble hearing, and 27% (95% CI OR = 1.19–1.36) and 49% (95% CI OR = 1.26–1.75) greater odds, respectively, of reporting difficulty with reviewing and comparing Medicare options. However, there was no difference in the frequency they reported reviewing their Medicare options compared with those with no trouble hearing.

Table 3.

Association Between Exposure of Self-Reported Trouble Hearing and Outcomes Related to Understanding Medicare from Adjusted Multivariate Analysisa

| Self-reported trouble hearing (Ref: no trouble) |

||

|---|---|---|

| A little trouble Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

A lot of trouble Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Primary outcome | ||

| How easy is Medicare to understand (1, very easy; 4, very difficult) | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| What they think they know about Medicare (1, everything you need; 5, Almost none of what you need) | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | 1.16 (1.01–1.34) |

| How easy to review compare Medicare options (1, very easy; 4, very difficult) | 1.27 (1.19–1.36) | 1.49 (1.26–1.75) |

| How often review Medicare options (1, at least one every year; 4, never) | .98 (.91–1.05) | 1.06 (.91–1.25) |

| Enough info compare health insurance options (1, completely agree; 4, completely disagree) | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) | 1.34 (1.13–1.59) |

| Satisfied with Medicare info availability (1, very satisfied; 5, very dissatisfied) | 1.21 (1.14–1.28) | 1.28 (1.07–1.53) |

| Has called 800-MEDICARE for information (Ref: No) | 1.06 (.97–1.16) | 1.08 (.90–1.30) |

| Has visited www.medicare.gov (Ref: No) | 1.02 (.95–1.09) | 1.26 (1.06–1.50) |

Note: All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, dementia, insurance, vision impairment, and number of chronic conditions.

From authors’ analysis of data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2017.

Regarding availability of information, those with a little or a lot of trouble hearing had 29% (95% CI OR = 1.20–1.39) and 34% (95% CI OR = 1.13–1.59) greater odds of disagreeing, respectively, that there was enough information to compare health options, compared with Medicare beneficiaries with no trouble hearing. Medicare beneficiaries with a little and a lot of trouble hearing have 1.21 (95% CI OR = 1.14–1.28) and 1.28 (95% CI OR = 1.07–1.53) times greater odds of being less satisfied, respectively, with the availability of information on Medicare. There is no difference in the odds of calling 1-800-MEDICARE among those who have trouble and do not have trouble hearing. However, those with a lot of trouble hearing are more likely to visit the www.medicare.gov website to receive more information than those with no trouble hearing. Full regression results are available in Supplementary Table S1.

The results of the sensitivity analysis comparing those who did and did not call 1-800-MEDICARE or visit medicare.gov for information showed the association between trouble hearing and understanding Medicare remains across all subpopulations. Results of the sensitivity analyses are available in Supplementary Table S2.

DISCUSSION

This analysis shows that Medicare continues to be difficult for almost one-third of Medicare beneficiaries to understand and navigate. Importantly, from this analysis it is clear that hearing loss is an important factor when considering barriers to understanding the Medicare program and appropriate solutions to address these challenges. For individuals with hearing loss there may be two reasons why Medicare is particularly difficult to understand. First, the existing tools available to facilitate understanding of the program are not designed for those with trouble hearing. One in five Medicare beneficiaries with hearing loss identified that their hearing made it difficult to find Medicare information. Efforts to address poor health literacy are often focused on using more accessible language that would not resolve the challenges in receiving and processing information for those with hearing loss.

Second, the coverage choices to address hearing loss in the Medicare program are limited, variable, and often buried in the small print. Treatment for hearing loss is not a covered service under traditional Medicare, but some MA programs are offering treatment for hearing loss as a supplementary benefit in their plans. In fact, in 2016, more than one-half (56%) of non-Medicaid MA enrollees were in plans with a hearing benefit.21 As evidenced in the analysis, compared with those without hearing loss, Medicare beneficiaries with hearing loss are more likely to be actively searching for coverage information through existing tools such as www.medicare.gov but feeling dissatisfied with what information is available. The inconsistency of hearing treatment coverage across the program may be adding to the difficulty and complexity of the Medicare program for beneficiaries with hearing loss who may be seeking treatment solutions.

Three-quarters of Medicare beneficiaries aged 70 years and older have clinically relevant hearing loss.5 Untreated hearing loss is associated with poor health outcomes22 and higher healthcare utilization and spending.23 Given this, it could be argued that the need for finding the most appropriate plan to address their needs is even more imperative for those with hearing loss to either receive treatment for their hearing loss and/or to be better protected from the out-of-pocket costs that may come with higher healthcare utilization. Further studies on the impact of hearing loss and health literacy on insurance plan selection and out-of-pocket spending outcomes is warranted.

Limitations

First, this study relied on self-reported hearing loss that likely underrepresents the Medicare population with hearing loss. Studies using objective hearing measures report a higher prevalence of clinically relevant hearing loss than self-reported levels in the population. However, having people with hearing loss not self-reported in the no trouble hearing group would likely dampen the effect of hearing loss on understanding Medicare if that association does exist.

Second, the question for trouble hearing is asked in the context of using a hearing aid for those who usually would wear one. We can therefore not determine whether using a hearing aid would assist in better understanding the Medicare program for those with hearing loss because we do not have information on their hearing ability or their understanding of Medicare without the use of the hearing aid.

Third, health literacy, defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,”8 is represented in this analysis by the limited questions available through the MCBS. These questions are not a validated instrument to measure health literacy in older adults. However, as identified in the NASEM workshop, there are no validated instruments to measure health literacy among older adults that capture the construct comprehensively.3

Finally, although we adjusted for cognitive impairment (diagnosis of dementia) in our multivariate model, it is likely that we were not able to fully account for the impact of cognitive impairment on understanding Medicare because many people with cognitive impairment go undiagnosed.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The CMS, with an awareness of low health literacy in the population, offer many resources for beneficiaries to better understand the Medicare program. However, health literacy has been considered through the narrow lens of simplifying language, which has not resolved some of the barriers to understanding Medicare for those with hearing loss. A crucial next step to addressing the barriers of health literacy among Medicare beneficiaries is to first measure it appropriately. Screening tools, particularly those used to quantify health literacy at the state or national level, need to encompass other barriers such as hearing loss by also considering oral communication challenges. In addition to measurement, greater outreach to individuals with hearing loss is required to develop appropriate materials and to ensure sufficient resources are made available to navigate and understand the program.

Finally, more needs to be done to make Medicare an understandable and accessible program for all beneficiaries. Combining the multiple parts of traditional Medicare (Parts A, B, and D) under one program with a single premium, deductible, and cost-sharing arrangement, and ensuring consistency of benefits across traditional Medicare and MA would substantially reduce the complexity of the program for beneficiaries.24,25

In conclusion, hearing loss impacts the lives of Medicare beneficiaries in many ways. This study found that hearing loss is associated with the ability to understand the Medicare program, review and compare options, and find necessary information to make informed choices. Choosing the appropriate health plan for one’s needs has significant implications on healthcare utilization and costs. Greater attention should be paid to the barriers in understanding the Medicare program for those with hearing loss. Further research is required to confirm and investigate the impact of hearing loss on lower health literacy, and to advance the measurement of health literacy to capture all elements of obtaining, processing, and understanding information.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1: Full Results for Multivariate Regression Models on the Association between Hearing Trouble and Health Literacy Outcomes.

Supplementary Table S2: Sensitivity Analysis Regression Stratified by Those Who Did and Did Not Seek Information on Medicare

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest: This study was funded in part by the Commonwealth Fund (Grant No. 20192345) and the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. Amber Willink received an honorarium from the American Speech and Hearing Association to speak at the ASHA convention. Nicholas S. Reed is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Clearwater Clinical.

Sponsor’s Role: The Commonwealth Fund and the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenthal D, Davis K, Guterman S. Medicare at 50—moving forward. N Engl J Med 2015;372(7):671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare plan finder gets an upgrade for the first time in a decade [2019. press release]. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/medicare-plan-finder-gets-upgrade-first-time-decade. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 3.National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Health Literacy and Older Adults: Reshaping the Landscape: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Quick guide to health literacy. https://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsbasic.htm. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- 5.Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1820–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage 2019 Spotlight: First Look. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cubanski J, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Part D: A First Look at Prescription Drug Plans in 2019. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Vol NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000–1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesser AK, Keene Woods N, Smothers K, Rogers N. Health literacy and older adults: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2016;2: 2333721416630492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speros CI. More than words: promoting Health literacy in older adults. J Issues Nurs 2009;14(3):5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10(10):537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Education Statistics. Health Literacy—Development and Administration. National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL); 2020. https://nces.ed.gov/naal/health_dev.asp. Accessed May 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baur C, Rubin D. Putting health literacy questions on the Nation’s Public Health Report Card. Paper presented at: 8th Annual Health Literacy Research Conference; October 13, 2016; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin FR. Hearing loss in older adults: who’s listening? JAMA 2012;307(11): 1147–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(4):293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCoy SL, Tun PA, Cox LC, Colangelo M, Stewart RA, Wingfield A. Hearing loss and perceptual effort: downstream effects on older adults’ memory for speech. Q J Exp Psychol A 2005;58(1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017 Data Userʼs Guide: Survey File. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav 2007;31(suppl 1)):S19–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willink A The high coverage of dental, vision, and hearing benefits among Medicare advantage enrollees. Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019861554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deal JA, Reed NS, Kravetz AD, et al. Incident hearing loss and comorbidity: a longitudinal administrative claims study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;145(1):36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed NS, Altan A, Deal JA, et al. Trends in health care costs and utilization associated with untreated hearing loss over 10 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;145(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis K, Schoen C, Guterman S. Medicare essential: an option to promote better care and curb spending growth. Health Aff 2013;32(5):900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willink A, DuGoff EH. Integrating medical and nonmedical services- the promise and pitfalls of the CHRONIC Care Act. N Engl J Med 2018;378 (23):2153–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Full Results for Multivariate Regression Models on the Association between Hearing Trouble and Health Literacy Outcomes.

Supplementary Table S2: Sensitivity Analysis Regression Stratified by Those Who Did and Did Not Seek Information on Medicare