Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by aberrant expansion of monoclonal plasma cells with high mortality and severe complications due to the lack of early diagnosis and timely treatment. Circulating miRNAs have shown potential in the diagnosis of MM with inconsistent results, which remains to be fully assessed. Here we updated a meta-analysis with relative studies and essays published in English before Jan 31, 2021. After steps of screening, 32 studies from 11 articles that included a total of 627 MM patients and 314 healthy controls were collected. All data were analyzed by REVMAN 5.3 and Stata MP 16, and the quality of included literatures was estimated by Diagnostic Accuracy Study 2 (QUADAS-2). The pooled area under the curve (AUC) shown in summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) analyses of circulating miRNAs was 0.87 (95%CI, 0.81–0.89), and the sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were 0.79, 0.86, 5, 0.27, 22, respectively. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis exhibited that “miRNA cluster”, patient “detailed stage or Ig isotype” accounted for a considerable proportion of heterogeneity, revealing the importance of study design and patient inclusion in diagnostic trials; thus standardized recommendations were proposed for further studies. In addition, the performance of the circulating miRNAs included in MM prognosis and treatment response prediction was summarized, indicating that they could serve as valuable biomarkers, which would expand their clinical application greatly.

Systematic Review Registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=234297, PROSPERO, identifier (CRD42021234297).

Keywords: biomarker, diagnosis, meta-analysis, microRNAs, multiple myeloma

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM), the second most common hematological malignancy (1), develops from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), through the malignant transformation of long-lived plasma cells deriving from memory B cells and plasma-blasts (2). Normal interactions between plasma cells and their environment (the bone remodeling chambers) enable the stability of normal plasma cell genotypes and phenotypes, which may be disrupted by multiple factors at a precursor stage of MM (MGUS, pre-MGUS state) leading to MM tumorigenesis (3). The risk of progression for MGUS is about 1% yearly and 10% for SMM in the first 5 years (4). Early treatment is of benefit, inhibiting disease progression but with non-negligible side effects (5), and a novel biomarker with high accuracy for early diagnosis is imperative.

As a member of non-coding RNAs, miRNAs are small RNA molecules that function as negative regulators of gene expression. The decrease or increase of specific miRNAs in MM is associated with the dysregulation of the target gene expression, reflecting their impact on tumor-suppression or promotion (6, 7). Circulating miRNAs have been explored as valuable tools for various tumor diagnoses and prognoses by several studies (8). Similarly, the diversification of circulating miRNA expression in MM has been investigated, indicating that miRNAs could serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers (9, 10). However, not every miRNA was eligible, and there was significant heterogeneity among the findings. We updated a meta-analysis to address whether the circulating miRNAs could be promising biomarkers for early detection of MM with the latest evidence and try to resolve the problems that contributed to heterogeneity in previous studies.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the guidance of the PRISMA 2020 Statement: an Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews (11), and registered on PROSPERO prior to the start.

Literature Search

Multiple databases (Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, SinoMed, CQVIP database, Wan Fang database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Clinical Trials.gov) were systematically searched for related studies and essays published in English up to Jan 31, 2021. Subject headings and all the free words of ‘multiple myeloma’, ‘microRNAs’, ‘sensitivity’, ‘specificity’, ‘predictive value’, ‘accuracy’, ‘diagnostic’, and ‘AUC’ were applied for the regular advanced search. To minimize search omissions, we searched ScienceDirect and ResearchGate and pored over the reference list of the articles cited in this review to look for potential studies.

Study Selection

Studies that met the following criteria were included: 1) all the MM patients were diagnosed according to standard diagnostic criterion; 2) control subjects were analyzed concurrently; 3) miRNA measured by qRT-PCR and the process clearly described; 4) same outcome: sensitivity, specificity, AUC; 5) specimens are limited to serum or plasma; and 6) sample size was given. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) different control groups; 2) reviews and meta-analysis; 3) abstracts, editorials, conference papers, and letters without valid data; 4) repeated articles; 5) not conducted on humans; 6) sample size was insufficient; 7) non-English literature. To avoid any selection bias, two independent authors decided whether to include or exclude a study when they reach a consensus; otherwise, a third author reviewed the article again and resolved the disagreement.

Quality Assessment of Literature and Data Extraction

The quality of the selected studies was assessed according to QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2) on RevMan (version 5.3, London, UK, RRID: SCR_003581) by two authors and illustrated in a graph. Also, basic information from eligible articles/supplementary materials (first authors, publication year, specimen, sample size, miRNAs, expression mode, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, patient information including Ig isotype, stage, study design, gender structure, and age range) was extracted by two authors independently using a standardized form and then reviewed by a third author in detail.

Statistical Analysis

The data of true positives (TPs), false positives (FPs), true negatives (TNs), and false negatives (FNs) of 32 miRNAs extracted from 11 individual studies were analyzed in REVMAN 5.3 and STATA (version MP16, Texas, USA, RRID : SCR_012763). The sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and area under the curve (AUC) were pooled with the random effects meta-analysis model. Total diagnostic accuracy was assessed by summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve with the sensitivity and specificity data of each qualified study. To evaluate the existence of heterogeneity, I2 over 50% and/or P-value of Q-test under 0.05 were set as statistically significant. Meta-regression was executed with univariable model and multivariate model respectively. Subgroup analyses were employed to dissociate the heterogeneity among the studies using the random-effects inverse-variance model with DerSimonian–Laird estimate of tau². All P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature Selection, Quality Assessment, and Study Characteristics

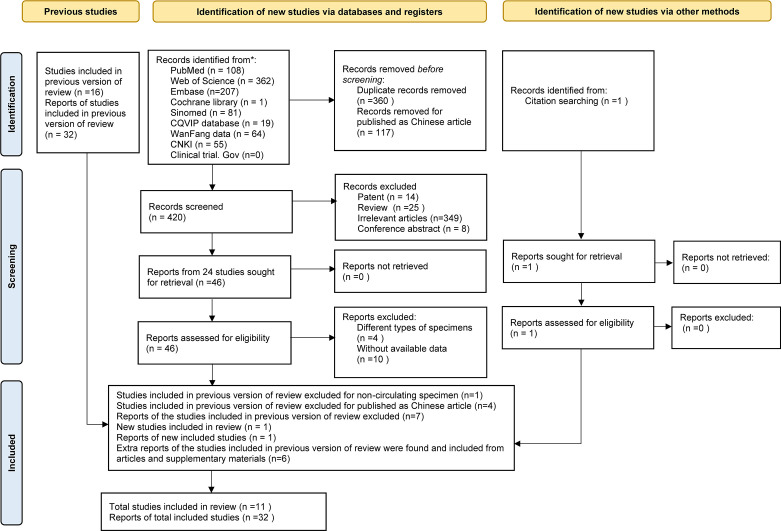

As the study search and selection process show in Figure 1 , a total of 898 articles were initially obtained; 897 studies were identified from Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, SinoMed, CQVIP database, Wan Fang Data, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Clinical Trials.gov, and 1 was acquired from reference lists of articles cited in this paper. All of the articles were imported into Zotero. After carefully screening for the title. abstract, and full-text, 117 Chinese articles, 360 duplicates, 14 patent, 25 reviews, 8 conference abstracts, 349 with irrelevant themes, 5 with different types of specimen, and 10 without available data were excluded. Finally, 32 miRNAs from 11 articles were included for this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

In comparison to the previous version of review (10), one report of a study for non-circulating specimen (12) and seven reports of four articles published in Chinese were excluded; and one report of a new study was included (13). The main information of circulating miRNA reports extracted from the qualified studies is displayed in Table 1 . Among these, six extra reports of the studies included in the previous version of review were found from the articles and supplementary materials (14, 18, 21, 22). Characteristics of MM patients and healthy controls are available in Table 2 . All the eligible articles were published before Jan 31, 2021 containing 627 MM patients and 314 healthy controls. The expression levels of miRNAs in serum (n = 27) or plasma (n = 5) were detected by qRT-PCR. Of these 32 studies, three studies evaluated miRNA clusters, whereas the others evaluated individual miRNA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies and the diagnostic power of miRNAs.

| No. | Author | Country | Year | Sample size | Sample | miRNA | Expression | Diagnostic power | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM | HC | AUC | SENC | SPEC | |||||||

| 1 | Li J (14) | China | 2020 | 23 | 18 | serum | miR-134-5P | ↑ | 0.812 | 0.870 | 0.667 |

| 2 | serum | miR-107 | ↑ | 0.766 | 0.564 | 0.889 | |||||

| 3 | serum | miR-15a-5p | ↑ | 0.804 | 0.870 | 0.610 | |||||

| 4 | Gupta N (15) | India | 2019 | 30 | 30 | serum | miR203 | ↓ | 0.930 | 0.833 | 0.833 |

| 5 | serum | miR143 | ↓ | 0.864 | 0.767 | 0.767 | |||||

| 6 | serum | miR144 | ↓ | 0.784 | 0.733 | 0.733 | |||||

| 7 | serum | miR199 | ↓ | 0.900 | 0.800 | 0.800 | |||||

| 8 | Shen X (16) | China | 2017 | 71 | 46 | serum | miR-4449 | ↑ | 0.885 | 0.789 | 0.913 |

| 9 | JIANG Y (17) | China | 2018 | 35 | 20 | plasma | miR-125b-5p | ↑ | 0.954 | 0.860 | 0.960 |

| 10 | plasma | miR-490-3p | ↑ | 0.866 | 0.600 | 0.850 | |||||

| 11 | Qu X (18) | China | 2014 | 40 | 20 | plasma | miR-483-5p | ↑ | 0.745 | 0.580 | 0.900 |

| 12 | plasma | miR-20a | ↓ | 0.740 | 0.630 | 0.850 | |||||

| 13 | Kubiczkova L (19) | Czech | 2013 | 103 | 30 | serum | miR-744 | ↓ | 0.715 | 0.728 | 0.667 |

| 14 | serum | miR-130a | ↓ | 0.722 | 0.575 | 0.900 | |||||

| 15 | serum | miR-34a | ↑ | 0.790 | 0.777 | 0.700 | |||||

| 16 | serum | let-7d | ↓ | 0.804 | 0.641 | 0.867 | |||||

| 17 | serum | let-7e | ↓ | 0.829 | 0.888 | 0.633 | |||||

| 18 | Yoshizawa S (20) | Japan | 2011 | 62 | 21 | plasma | miR-92a | ↓ | 0.981 | 0.919 | 0.991 |

| 19 | Jones Cl (21) | UK | 2012 | 24 | 13 | serum | miR-720 | ↑ | 0.911 | 0.872 | 0.923 |

| 20 | serum | miR-1308 | ↓ | 0.892 | 0.821 | 0.923 | |||||

| 21 | Hao M (22) | China | 2015 | 108 | 56 | Serum | miR-4254 | ↑ | 0.926 | 0.793 | 0.985 |

| 22 | Serum | miR-19a | ↓ | 0.910 | 0.773 | 0.897 | |||||

| 23 | Serum | miR-92a | ↓ | 0.830 | 0.724 | 0.869 | |||||

| 24 | Serum | miR-135b-5p | ↑ | 0.810 | 0.667 | 0.833 | |||||

| 25 | Serum | miR-214-3p | ↑ | 0.720 | 0.625 | 0.833 | |||||

| 26 | Serum | miR-3658 | ↑ | 0.720 | 0.714 | 0.667 | |||||

| 27 | Serum | miR-33b | ↑ | 0.630 | 0.633 | 0.815 | |||||

| 28 | Y u J (13) | China | 2014 | 40 | 30 | serum | miR-202 | ↓ | 0.711 | 0.800 | 0.600 |

| 29 | Sevcikova S (23) | Czech | 2013 | 91 | 30 | Serum | miR-29a | ↑ | 0.832 | 0.880 | 0.700 |

| miRNA cluster | |||||||||||

| 30 | Kubiczkova L (19) | Czech | 2013 | 103 | 30 | serum | miR-34a+let7e | N/A | 0.898 | 0.806 | 0.867 |

| 31 | Jones Cl (21) | UK | 2014 | 24 | 13 | serum | miR-1308/miR-720 | N/A | 0.986 | 0.974 | 0.923 |

| 32 | Hao M (22) | China | 2015 | 108 | 56 | Serum | miR-4254/miR-19a | N/A | 0.950 | 0.917 | 0.905 |

AUC, area under the curve; HC, health control; MM, multiple myeloma; N/A, Not applicable; SENS, sensitivity; SPEC, specificity; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients and health controls included.

| Author | MM Ig Isotype | MM stage | Newly diagnosed or untreated | Cohort study | Gender (male, female) | Age (median, range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM | HC | MM | HC | |||||

| Li J (14) | IgG: 9, IgA: 7, Light chain only: 7 | D-S, I: 3; II 5; III: 15 | NA | NA | 16, 7 | 11, 7 | 66.5 (42–86) | 65.6 (53–79) |

| Gupta N (15) | NA | ISS, I: 4; II 14; III: 12 | YES | NA | 17,13 | 22, 8 | 59 (33-76) | 44 (33-55) |

| Shen X (16) | NA | NA | YES | YES | 13, 10 | NA | 62 (39-86) | 63 (40-76) |

| JIANG Y (17) | NA | D-S, I: 10; II 16; III: 19 | YES | NA | 23, 12 | 8, 12 | 59 (35-75) | (17-63) |

| Qu X (18) | IgG: 18, IgA: 10, IgD: 1, Light chain only: 10, non-secretory: 1 | ISS, I: 7; II: 13; III: 20 | YES | NA | 23, 17 | 10, 10 | 59 (23-80) | 60 (35-75) |

| Kubiczkova L (19) | IgG: 54, IgA: 28, IgD: 3, IgM: 2,Light chain only: 11 | ISS, I: 35; II: 29; III: 39 | YES | YES | 51, 52 | 14, 16 | 66 (47-83) | 55 (45-64) |

| Yoshizawa S (20) | IgG: 26, IgA: 12, IgD:3, B-J protein: 14, non-secretory: 4; plasma cell leukemia: 3 | NA | YES | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jones Cl (21) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12, 12 | 5, 8 | 73.5 (58-89) | 47.7 (42-58) |

| Hao M (22) | IgG: 51, IgA: 29, IgD: 8, Light chain only: 18, non-secretory: 2 | ISS, I: 18; II: 39; III: 50, not classified: 1. | YES | YES | NA | NA | (33-83) | 52 (40-78) |

| Y u J (13) | IgG: 22, IgA: 13, IgD: 5 | NA | NA | NA | 25, 15 | 18, 12 | 62 (35-87) | 63 (40-86) |

| Sevcikova S (23) | IgG: 46, IgA: 22, IgD: 2 Light chain only: 16, non-secretory: 2, Biclonal:1 | ISS, I: 28; II: 32; III: 26, not classified: 5. | YES | YES | 49, 42 | 14, 16 | 63.9 (41-48) | 55.5 (45-64) |

D-S, Durie-salmon stage; HC, health control; ISS: International Staging System stage; MM, multiple myeloma; NA, not available.

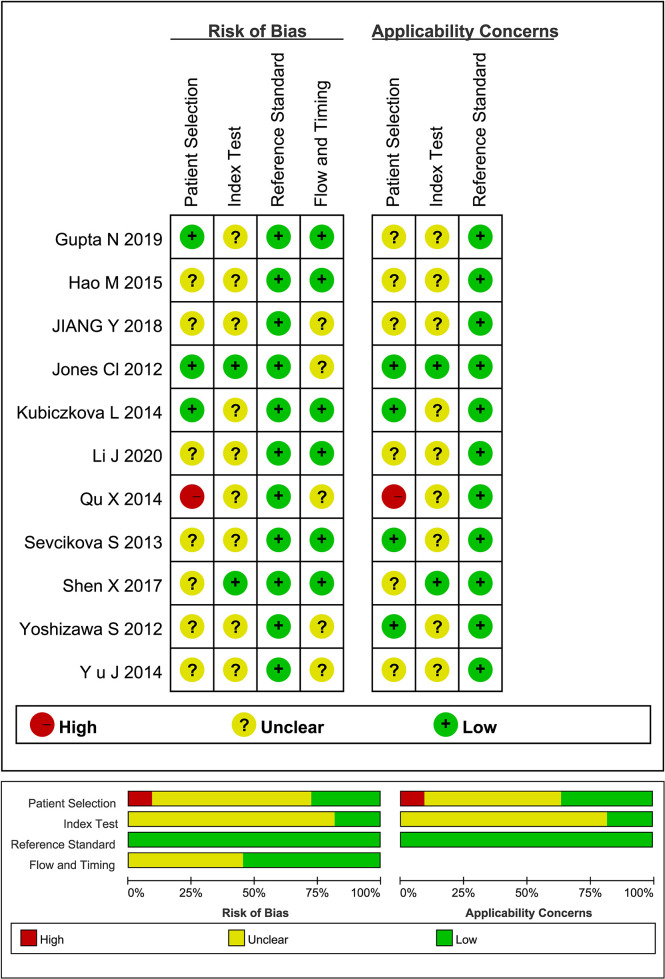

Quality assessment of qualified literatures by QUADAS-2 tool reveal that the overall quality of the studies included was acceptable, but with a few unignorable flaws and uncertainties ( Figure 2 ). Some of the literatures did not clarify the study design, the patient information (stage/Ig isotype/prior to any treatment), and whether there was an appropriate time interval between the reference standard and miRNA detection. Besides, the absence of suspected cases in some of the literatures may lead to bias in the evaluation of diagnostic power.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of qualified studies by QUADAS-2 tool.

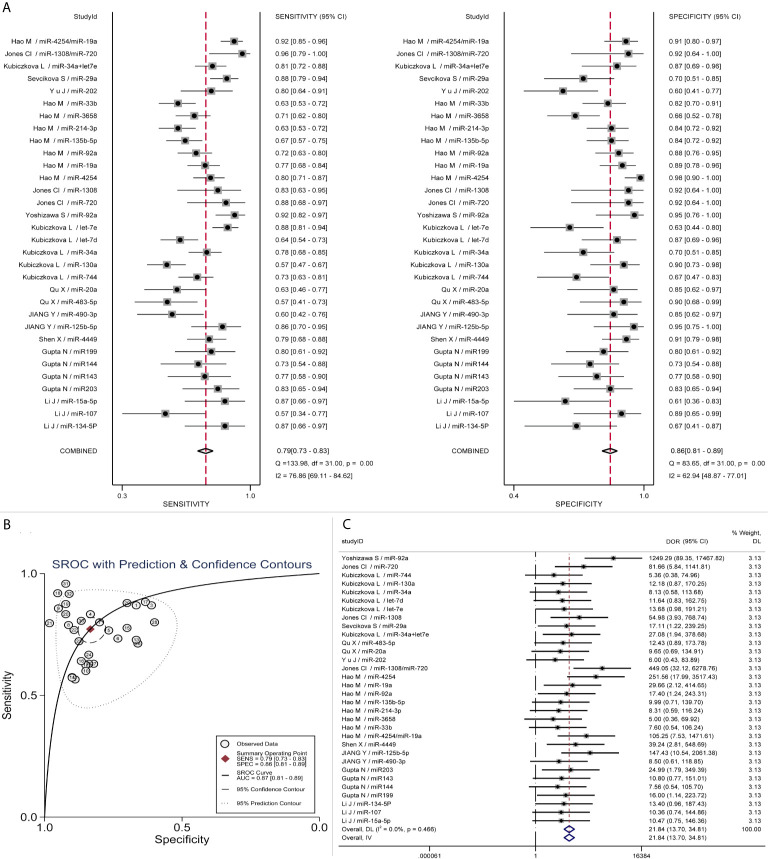

Diagnostic Performance Evaluation

All the data were included to calculate the combined diagnostic accuracy of miRNAs by STATA MP 16 software. As Forest plots present, the sensitivity and specificity of miRNAs in various studies were significantly heterogeneous (sensitivity: I2 = 76.86%, p < 0.01; specificity: I2 = 62.94%, p < 0.01). By recombining the data with random effect models, the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.79 (95%CI, 0.73–0.83) and 0.86 (95%CI, 0.81–0.89) respectively ( Figure 3A ). Spearman correlation analysis was performed on the Logit conversion values of sensitivity and false-positive rate to identify the source of heterogeneity, and no threshold effect was suggested (coefficient = −0.0817, p = 0.657). Based on the SROC curve, the pooled AUC of miRNAs in MM diagnosis was 0.87 (95%CI, 0.81–0.89), PLR 5 (95%CI, 4–6), NLR 0.27 (95%CI, 0.23–0.33) ( Figure 3B ). The pooled DOR was 22 (95%CI, 14–35) using a random effect model ( Figure 3C ).

Figure 3.

Pooled diagnostic parameters of all microRNA studies. (A) Forest plot of Sensitivity and Specificity; (B) SROC curve; (C) Forest plot of DOR.

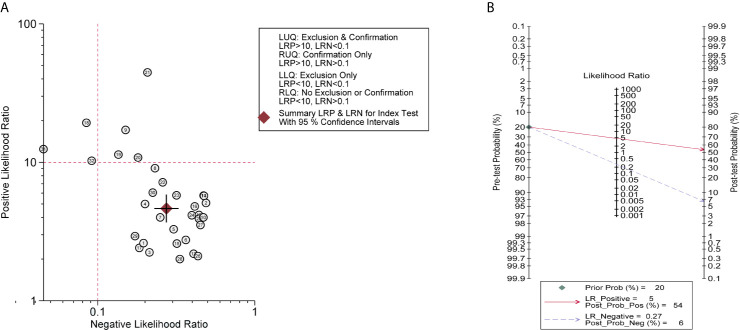

Summary LRP and LRN for Index Test are depicted in Figure 4A , demonstrating that a small number of miRNAs (No. 9/18/19/20/21/31/32) contribute to the confirmation or exclusion of MM, whereas the others appear to be under-achieving. The pre-test and post-test probabilities were evaluated by Fagan’s nomogram, presenting that when the prior probability was 20%, post-test probabilities were 54 and 6% for positive and negative circulating miRNAs in MM patients, respectively ( Figure 4B ).

Figure 4.

Clinical utility of circulating miRNAs. (A) Summary LRP & LRN for Index Test showed that a few miRNAs (No. 9/18/19/20/21/31/32) had relatively good clinical diagnostic value. LLQ, left lower quadrant; LRN, likelihood ratio negative; LRP, likelihood ratio positive; LUQ, left upper quadrant; RLQ, right lower quadrant; RUQ, right upper quadrant; (B) Fagan nomogram of Pre-test probability and post-test probability.

Sensitivity Analysis and Heterogeneity Exploration

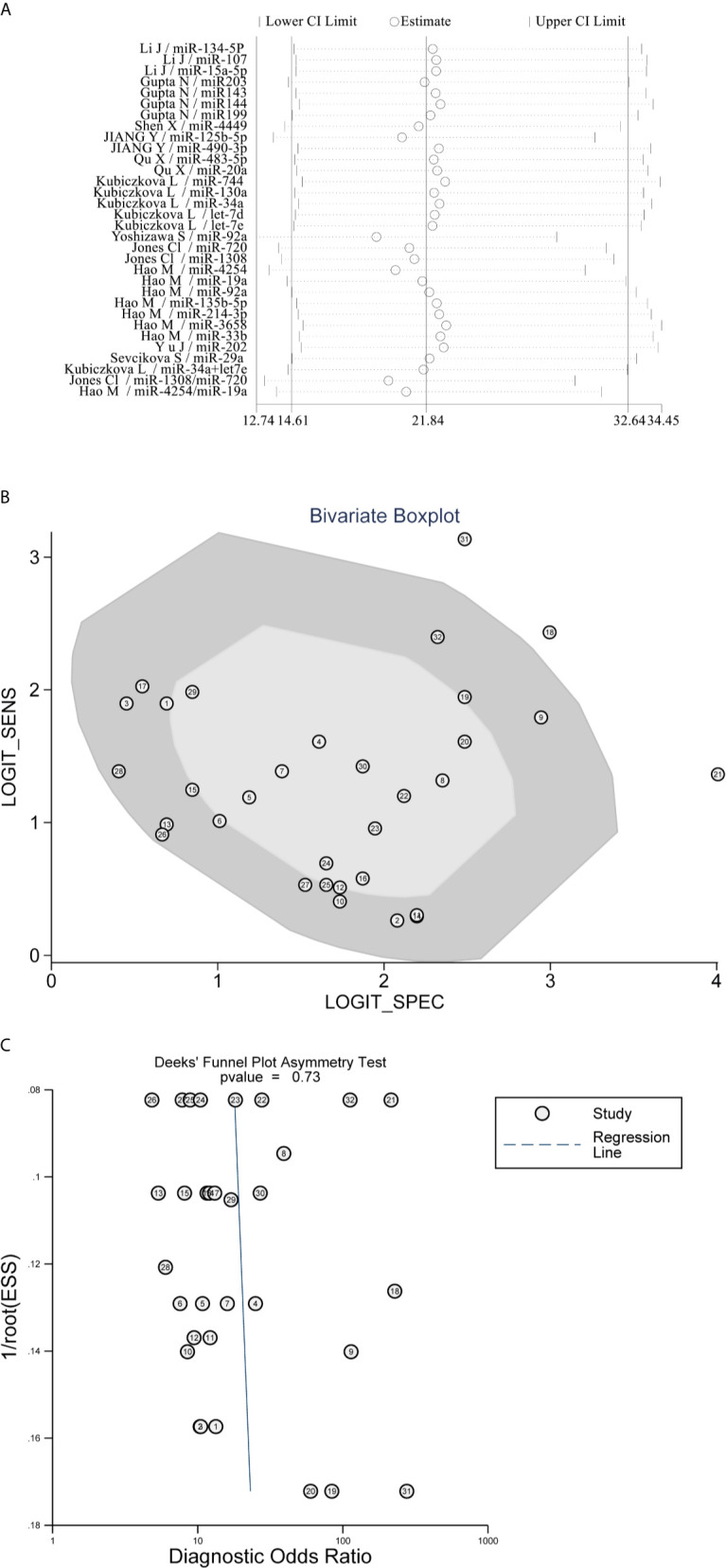

Then, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the combined DOR. After subtracting the No. 18 study with the maximal deviation, the DOR value changed from 22 to 19, presenting that there was no significant change in the results ( Figure 5A ). Similarly, other studies, excluding one, showed at the time consistent combinatorial DOR without significant fluctuations. However, the fixed-effect model had a greater influence on the pooled DOR than the random-effect model (DOR, 17 vs. 22), indicating that an improper data analysis method may have a great impact on the pooled results. Among these miRNAs, miR-4254 was the most promising diagnostic biomarker with 0.80 sensitivity (95%CI, 0.71–0.87), 0.98 specificity (95%CI, 0.90–1.0) and 252 DOR (95%CI, 18–3517). Bivariate boxplot revealed that some of the studies with relatively higher AUC (No.18/21/31) showed stronger heterogeneity ( Figure 5B ). Meanwhile, publication bias was not found by Deek’s funnel plot asymmetry test (P = 0.73) ( Figure 5C ).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis and Heterogeneity exploration. (A) Sensitivity Analysis showed that the combination results were stable; (B) Bivariate Boxplot revealed that No.18/21/31 studies presented strong heterogeneity; (C) Deek’s Funnel Plot Asymmetry Test found no publication bias.

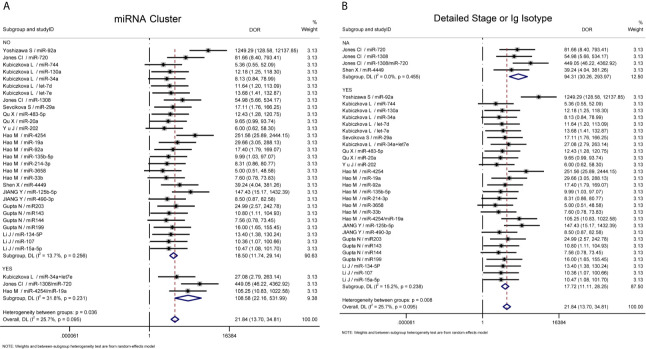

Further heterogeneity analysis by meta-regression according to “miRNA cluster”, “ detailed stage or Ig isotype”, “newly diagnosed or untreated”, “determined cohort study design”, “sample size>30”, “serum or plasma” and “ethnicity” were conducted with univariable model, demonstrating that “miRNA cluster”, “detailed stage or Ig isotype” and “determined cohort study design” reached statistical significance. Subsequently, these three variables were analyzed by meta-regression with multivariate model, and there were significant differences between the “miRNA cluster” subgroups and the “detailed stage or Ig isotype” subgroups ( Table 3 ). Then subgroup analyses based on sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and DOR were performed using the random-effects inverse-variance model with DerSimonian–Laird estimate of tau² to investigate the specific heterogeneity existing within and between subgroups, and the results are displayed in Table 4 . The diagnostic parameters of miRNA clusters were better than the single miRNA subgroup, whereas the parameters of the detailed patient information subgroup and determined cohort study design subgroup were inferior than their contrasts. The DOR-based subgroup analysis results are shown in Figure 6 .

Table 3.

Meta-regression with univariable model and multivariate model.

| Variable | Coef. | Std. Err | t | P>|t| | 95% CI | Tau² | I-squared res | Adj R-squared | exp(b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable model | |||||||||

| miRNA cluster | 1.77 | 0.76 | 2.32 | 0.028 | [0.21, 3.33] | 0.24 | 15.24% | 48.02% | 5.87 |

| _cons | 2.92 | 0.23 | 12.47 | 0.000 | [2.44, 3.40] | 18.5 | |||

| Detailed stage or Ig isotype | -1.67 | 0.66 | -2.52 | 0.017 | [-3.02, -0.31] | 0.20 | 12.92% | 57.11% | 0.19 |

| _cons | 4.54 | 0.62 | 7.31 | 0.000 | [3.27, 5.81] | 94.31 | |||

| Cohort study | -0.46 | 0.48 | -0.97 | 0.340 | [-1.43, 0.51] | 0.47 | 25.84% | -0.73% | 0.63 |

| _cons | 3.31 | 0.34 | 9.84 | 0.000 | [2.62, 4.00] | 27.51 | |||

| Multivariate Model | 0.00 | 0.00% | 100.00% | ||||||

| miRNA profile | 1.20 | 0.74 | 1.63 | 0.115 | [-0.35, 2.65] | 3.32 | |||

| Detailed stage or Ig isotype | -2.42 | 0.74 | -3.30 | 0.003 | [-3.75, -0.63] | 0.09 | |||

| Cohort study | -0.39 | 0.42 | -0.92 | 0.363 | [-1.72, 0.22] | 0.68 | |||

| _cons | 5.36 | 0.72 | 7.45 | 0.000 | [4.01, 6.99] | 213.70 |

Adj R-squared, Adjusted R-Squared; CI, confidence interval; Coef, coefficient; I-squared res, I-squared residual; Std. Err, standard error.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis.

| Subgroup | SENS [95% CI] | SPEC [95% CI] | AUC [95% CI] | DOR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA profile | ||||

| Single miRNA | 0.77 [0.70, 0.82] | 0.85 [0.80, 0.89] | 0.84 [0.79, 0.88] | 19 [12, 29] |

| I²/p-value | 0.0%/0.99 | 6.8%/0.361 | 0.0%/0.928 | 13.7%/0.256 |

| miRNA cluster | 0.92 [0.77, 0.98] | 0.90 [0.75, 0.97] | 0.96 [0.87, 0.99] | 109 [22, 532] |

| I²/p-value | 38.1%/0.199 | 0.0%/0.909 | 21.1%/0.282 | 31.8%/0.231 |

| P (between subgroup) | 0.047 | 0.440 | 0.021 | 0.036 |

| Stage or Ig isotype | ||||

| not detailed | 0.89 [0.74, 0.96] | 0.92 [0.81, 0.97] | 0.93 [0.84, 0.98] | 94 [30, 294] |

| I²/p-value | 31.7%/0.222 | 0.0%/1.000 | 21.6%/0.281 | 0.0%/0.455 |

| detailed | 0.77 [0.70, 0.82] | 0.84 [0.79, 0.89] | 0.84 [0.79, 0.88] | 18 [11, 28] |

| I²/p-value | 0.0%/0.968 | 6.1%/0.373 | 0.0%/0.863 | 15.2%/0.238 |

| P (between subgroup) | 0.099 | 0.152 | 0.071 | 0.008 |

| Cohort study design | ||||

| not detailed | 0.81 [0.74, 0.87] | 0.87[0.79, 0.92] | 0.88 [0.82, 0.93] | 28[13,60] |

| I²/p-value | 34.4%/0.442 | 17.6%/0.252 | 14.1%/0.292 | 46.2%/0.022 |

| detailed | 0.7 [0.68, 0.83] | 0.84 [0.77, 0.90] | 0.83 [0.75, 0.88] | 17 [10, 31] |

| I²/p-value | 0.0%/0.951 | 0.0%/0.648 | 0.0%/0.936 | 0.0%/0.635 |

| P (between subgroup) | 0.340 | 0.649 | 0.185 | 0.346 |

| Overall | 0.79 [0.73, 0.83] | 0.86 [0.81, 0.89] | 0.87 [0.81, 0.89] | 22 [14, 35] |

| I²/p-value | 0.0%/0.839 | 0.0%/0.475 | 0.0%/0.670 | 25.7%/0.095 |

AUC, area under the curve; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; SENS, sensitivity; SPEC, specificity.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis. (A) Subgroup analysis based on DOR sorted by “miRNA cluster”; (B) Subgroup analysis based on DOR sorted by “detailed stage or Ig isotype”. NA, not available.

Circulating miRNAs in MM, MGUS, and SMM

In order to investigate the ability of the included circulating miRNAs to discriminate MM from MGUS/SMM, we summarized their distributional and differential diagnostic data among those disease states. Between the MM and MGUS groups, the levels of miR-20, miR-15a, and miR-92a were significantly different. In ROC analysis, the individual miRNAs did not exhibit substantial discriminative performance, which would be improved by the combination of miRNAs and other clinical parameters. The combination of miR-107, miR-15a-5p, and hemoglobin gained the best differential performance with AUC = 0.954 (14), and the combination of miR-1246 and miR-1308 ranked second with AUC = 0.725 (21). For MM and SMM, the expression level of miR-92a was significantly different, but the differential diagnostic value remains to be verified (20). For MGUS and SMM, Manier et al. found significant differences in the expression levels of miR-107, miR-92a, and miR-125a in circulating exosomes (24); however, the included serum or plasma miRNAs have not shown any differential diagnostic value ( Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Circulating miRNAs in MM, MGUS, and SMM.

| Author | Sample size | miRNAs | Distributional or differential diagnostic data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM vs MGUS | MM | MGUS | ||

| Li J (14) | 23 | 16 | miR-134-5P | ROC: AUC=0.489 (p=0.909) |

| miR-107 | ROC: AUC=0.427 (p=0.441) | |||

| miR-15a-5p | ROC: AUC=0.557 (p=0.549) | |||

| miR-134-5P + miR-107 + miR-15a-5p | ROC: AUC=0.550 (p=0.095) | |||

| mir-107 + mir-15a-5p + Hb | ROC: AUC=0.954 (p=0.000), sensitivity=0.913, specificity=0.917 | |||

| Kubiczkova L (19) | 103 | 57 | miR-744 | MM: 473, MGUS: 371, fold change between MM/MGUS: 1.27 |

| miR-130a | MM: 5618, MGUS: 6232, fold change between MM/MGUS: 0.90 | |||

| miR-34a | MM: 176, MGUS: 192, fold change between MM/MGUS: 0.92 | |||

| let-7d | MM: 1944, MGUS: 1863, fold change between MM/MGUS: 1.04 | |||

| let-7e | MM: 4222, MGUS: 3521, fold change between MM/MGUS: 1.20 | |||

| Yoshizawa S (20) | 62 | 22 | miR-92a | One-way analysis of variance: p=0.0005 |

| Jones Cl (21) | 24 | 15 | miR-720 | ROC: AUC=0.528 (p=0.773) |

| miR-1308 | ROC: AUC=0.572 (p=0.453) | |||

| miR-1246 | ROC: AUC=0.628 (p=0.184) | |||

| miR-1308/miR-720 | ROC: AUC=0.597 (p=0.312) | |||

| miR-1246/miR-1308 | ROC: AUC=0.725(P< 0.05), sensitivity=0.792, specificity=0.667 | |||

| MM vs SMM | MM | SMM | ||

| Yoshizawa S (20) | 62 | 8 | miR-92a | One-way analysis of variance: p=0.0496 |

| Zhang Z (25) | 20 | 20 | let-7d-5p | Mann‐Whitney U test and one‐way analysis of variance: p=0.354 |

| miR-20a-5p | Mann‐Whitney U test and one‐way analysis of variance: p=0.402 | |||

| MGUS vs SMM | MGUS | SMM | ||

| Yoshizawa S (20) | 22 | 8 | miR-92a | One-way analysis of variance: p=0.2959 |

| Manier S (24) | 4 | 4 | miR-107 | p < 0.05 |

| miR-92a | p < 0.05 | |||

| miR-125a | p < 0.05 | |||

AUC, area under the curve; Hb, hemoglobin; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; ROC, receiver operator characteristic curve; SMM, smoldering multiple myeloma.

Discussion

Although survival of MM patients have been improved with the rapid advances of therapeutic strategy and supportive care, myriad patients still suffer from relapsed/refractory MM, entailing a reliable biomarker for early diagnosis. The remarkable impact of miRNA on protein expression is emerging with the discovery that about one-third of human encoding genes are regulated by miRNAs (26). Pioneering studies have found a mass of specific miRNAs carried by circulating microparticles significantly distinct from their maternal cells, depicting an interesting transfer pathway for the gene-regulating function of miRNAs from microparticles releasing cells to the target cells (27).

MicroRNAs transfer between MM plasma cells and bone marrow microenvironment, enabling the development and metastasis of malignancy through messenger RNA destruction or translation inhibition (28, 29). Circulating microRNAs have been applied in hematological diseases as diagnostic biomarkers due to their reliable stability and non-invasive properties (30). In recent years, the important role of circulating miRNAs in MM diagnosis has received considerable attention; however, the results vary and leave questions open (10). We updated this meta-analysis to figure out whether the circulating miRNAs could be promising means for early detection of MM with the latest evidence.

The diagnostic performance of miRNAs differed in this meta-analysis; among the top three individual miRNAs, miR-4254 was the highest [DOR = 252, 95% CI = (18,3517)] followed by miR-125b-5p [DOR = 147, 95% CI = (11,2061)], then miR-720 [DOR = 82, 95% CI= (6,1142)], whereas miR-3658 was the lowest [DOR = 5, 95% CI = (0.36,70)]. The miRNA cluster exhibited better diagnostic performance in subgroup analysis, with the combined parameters (sensitivity, 0.92; specificity, 0.90; AUC, 0.96; DOR 109) being far beyond individual miRNAs (sensitivity, 0.77; specificity, 0.85; AUC, 0.84; DOR 19).

The pooled sensitivity, specificity, AUC, PLR, NLR, and DOR were 0.79, 0.86, 0.87, 5, 0.27, and 22, respectively, consistent with the previous meta-analysis (10). Summary LRP and LRN for Index Test suggest a small number of studies have relatively high value for diagnosis conformation and/or exclusion. The Fagan nomogram of post-test probability also indicated that circulating miRNAs were of relatively good diagnostic value but still had room for improvement. Researchers found that the tests based on serum or plasma did not show significant differences, nor between ethnic groups; and our meta-analysis confirmed it.

However, the quality assessment of literatures presents a few ignorable flaws and uncertainties, which are somewhat inconsistent with the results of the previous meta-analysis (10), possibly because of the different versions of evaluation tools or the strictness in our assessment. We found that some of the literatures did not specify the study design, patient information (stage/Ig isotype/treatment information), or the time interval between the reference standard and miRNA detection. Besides, the absence of suspected cases in some of the studies may lead to bias in evaluation.

The combined diagnostic power did not fluctuate significantly in sensitivity analysis. The DOR value only changed from 22 to 19 even when the study with the greatest deviation was eliminated. To dissociate the sources of heterogeneity, a publication bias assessment was performed and no publication bias was found (p = 0.73). Inevitably, the exclusion of non-English literatures may also lead to selection bias. However, significant differences were found in the “miRNA cluster” and “detailed stage or Ig isotype” subgroups through meta-regression with univariable model and multivariate model (p < 0.05), but not in the “cohort study” and “newly diagnosed and untreated” subgroups, which may also be influenced by the limited number of studies included in each subgroup. Besides, no significant differences were found in the “specimen” and “ethnicity” subgroups, consistent with previous studies. These results reveal that the study design and the enrolment of patients and healthy controls may have an impact on the diagnostic value of the index to be assessed, and a standardized recommendation is imperative.

At present, the efficacy of early treatment determined by the free light chain ratio for the precursor-stage of MM (MGUS or SMM) to improve longevity and health-related quality of life is still unclear (31, 32), and distinguishing symptomatic multiple myeloma from those conditions is of great importance. In our summary, not much distributional or differential diagnostic evidence of circulating miRNAs in MM, MGUS and SMM were found. Although miRNA expression levels differed significantly, no individual miRNA exhibited excellent differential diagnostic ability, indicating that this area needs to be further explored with more meticulous design for subject enrolment. Moreover, a variety of diseases such as inflammation (33), cardiovascular diseases (34), or other non-cancerous illnesses (35) may also alter miRNA profile and level, which should be taken into account by researchers when setting up control groups.

The past decade has seen remarkable achievements in the understanding of miRNAs in MM, including their various targets, effects, and dysregulation modes in disease development and progression. Some miRNAs, such as miR-20a, miR-19a, miR-92a, and miR-214-3p act as oncomiR playing important roles in anti-apoptosis, proliferation, migration, and invasion. Other miRNAs, including miR-15a-5p, miR203, miR144, miR199, miR-483-5p, miR-34a, miR-33b, miR-202, and miR-29a act as tumor suppressors. Also, some miRNAs are involved in the development of bone marrow microenvironment in MM; for example, miR143 and miR-29a promote angiogenesis and osteoblast differentiation (36, 37), miR199 neutralizes the oncogenic effect of bone marrow stromal cells (38), and miR-92a is essential for B cell development (39). These results provide valuable resources for the investigation of the etiology and treatment methods for MM. Interestingly, the role of miR-125b-5p in MM is still controversial since it has the ability to inhibit the growth and survival of MM cell and promote apoptosis and autophagy-associated cell death by targeting IRF4 and its downstream effector BLIMP-1 (40), but miR-125b-5p may generate counterproductive effects through different target genes or signaling pathways; it promotes MM progress by increasing p53 mRNA and protein and attenuating MM cell death in response to dexamethasone (41). Further exploration of miRNAs may enrich our perspective. More details are listed in Table 6 .

Table 6.

Summary of studies on the targets and functions of miRNAs included.

| miRNA | Location | Targets | Functions of miRNA in multiple myeloma |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15a-5p | 13q14.2 | BCL-2, VEGF-A, PHF19, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, CDC25A | Cell growth suppression and apoptosis promotion (42, 43) |

| miR203 | 14q32.33 | CREB1, VCAN | Inhibit myeloma cell proliferation (44). |

| miR143 | 5q32 | HDAC7 | Promotes angiogenesis and osteoblast differentiation (36). |

| miR144 | 17q11.2 | c-MET, MEF2A, VCAN | Inhibits proliferation, angiogenesis, colony formation; promotes apoptosis (45, 46). |

| miR199 | 9q34.11 | VCAN | Neutralizes the oncogenic effect of bone marrow stromal cells (38). |

| miR-125b-5p | 11q24.1 or 21q21.1 | IRF4, BLIMP-1, TP53 | Inhibits the growth and survival of MM cell, promotes apoptosis and autophagy-associated cell death by targeting IRF4 and its downstream effector BLIMP-1 (40) |

| Promotes MM progress by increasing p53 mRNA and protein, and attenuates MM cell death in response to dexamethasone (41). | |||

| miR-483-5p | 11p15.5 | ZNF197, ABCF2 | Reduces cell viability, migration and colony formation (47). |

| miR-20a | 13q31.3 | PTEN, EGR2, SENP1, SOMO, cyclin D1 | Promotes cell proliferation and migration. inhibits cell apoptosis and alters cell cycle (48–50). |

| miR-34a | 1p36.22 | c-MYC, BCL-2, NoTCH1, CDK6, TP53, SIRT1, | Promotes apoptosis and represses proliferation (51, 52). |

| miR-19a | 13q31.3 | SOCS-1, BIM, RHOB, CLTC, PSAP, PPP6R2 | Inhibits apoptosis, promotes proliferation and migration (53, 54). |

| miR-92a | 13q31.3 | BIM | It’s essential for the development and survival of B cells, possess anti-apoptotic effect (39). |

| miR-214-3p | 1q24.3 | MCL1, PSMD10, ASF1B | Promotes MM progression by overexpression in myeloma fibroblasts (55). |

| miR-33b | 17p11.2 | PIM-1 | Inhibits cell viability, migration, and colony formation (56). |

| miR-202 | 10q26.3 | BAFF | Inhibits myeloma cell survival, growth, and adhesion (57). |

| miR-29a | 7q32.3 | VASH1, c-MYC | Promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis (37), mediates anti-tumor activities in MM cells by targeting c-Myc (58). |

MM, multiple myeloma.

Due to the important role of miRNAs in the tumorigenesis and progression of MM, circulating miRNAs have also shown their prognostic ability in MM, expanding their clinical application for identifying high-risk MM patients. As shown in Table 7 , several studies have demonstrated that patients with different levels of miR-483-5p, miR-744, let-7e, miR-19a, miR-92a, miR-33b, miR-214, or miR-20a appeared with quite different survival rates.

Table 7.

The prognostic value of circulating miRNAs in multiple myeloma.

| Author | Sample size | miRNA | Expression with Poor prognosis | PFS | OS | Other outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Low | High | ||||||

| Qu X (18) | 40 | 15 | 25 | miR-483-5p | High | High: 15 months Low: 20 months p=0.025 | Associated with ISS staging, p<0.05 | |

| 33 | 14 | 19 | miR-20a | N/A | High: 16 months Low: 15 months p>0.05 | |||

| Kubiczkova L (19) | 103 | 43 | 60 | miR-744 | Low | HR: 0.67 (95%CI, 0.55-0.82), p<0.0001 | TTP: HR 0.69 (95%CI, 0.58-0.82), p<0.0001 | |

| 103 | 52 | 51 | let-7e | Low | HR: 0.61 (95%CI, 0.42-8.83), p=0.002 | TTP: HR 0.55 (95%CI, 0.42-0.72), p<0.0001 | ||

| Hao M. (22) | 103 | 45 | 58 | miR-19a | Low | HR: 2.79 (95%CI, 1.42-5.47), p=0.003 | HR: 2.99 (95%CI, 1.17-7.69), p=0.023 | |

| Yoshizawa S (59) | 90 | 62 | 28 | miR-92a | Low | Low: 15.8 months High: 48 months p= 0.011 | ||

| Hao M (60) | 158 | miR-33b | High | Favorite PFS significantly | Favorite OS significantly | |||

| 158 | miR-19a | High | Favorite PFS significantly | Favorite OS significantly | ||||

| 158 | miR-4254 | N/A | Non-significance | Non-significance | Lower in healthy and complete remission patients compared to newly diagnosed and relapsed patients significantly | |||

| Hao M (61) | 108 | miR-135b | N/A | Non-significance | Non-significance | Correlated with grades of lytic bone lesions (r=0.404, p<0.001) | ||

| 108 | 35 | 73 | miR-214 | High | High: 8 months Low: 22 months p=0.015 | High: 15 months Low: 28 months p=0.002 | Correlated with grades of lytic bone lesions (r=0.455, p<0.0001). | |

| Huang J (62) | 28 | miR-20a | High | RFS: P=0.01 | ||||

| Ren Y (63) | 60 | 45 | 15 | miR-720 + miR-1246 | High | p<0.05 | ||

| Rocci A (64) | 234 | miR-720 | N/A | HR: 0.89 (95%CI, 0.79-1.01), p=0.077 | HR: 0.91 (95%CI, 0.77-1.07), p=0.26 | |||

CI, confidence interval; EFS, event-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; MM, multiple myeloma; N/A, Not applicable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, Relapse-free survival; TTP, time to progression.

More interestingly, the expression levels of miR-19a, miR-744-5p, miR-143-5p, and miR-92a, had significantly different outcomes in bortezomib-based treatment (22, 65–67). Patients with higher serum levels of miR-214 had extended overall survival upon bisphosphonate-based therapy (68). In patients with autologous stem-cell transplantation, the lower level of miR-15a on day 0 was associated with the shorter time to engraftment, and miR-20a decreased at complete remission (69, 70). These results demonstrate that the expression patterns of circulating microRNAs are valuable markers for predicting treatment response. See Table 8 for details.

Table 8.

Application of circulating miRNAs in specific treatment of multiple myeloma.

| Author | miRNA | Sample size | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang Y (17) | miR-125b-5p | Total: 35 | Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, followed by thalidomide Maintenance | EFS: High, 8 months; low, 13 months, p=0.02 |

| miR-490-3p | Total: 35 | EFS: High, 12 months; low, 13 months, p=0.23 | ||

| Hao M. (22) | miR-19a | High level: 23 Low level: 30 | Bortezomib-based | Patients with low miR-19a had significantly extended PFS (NR vs. 10.0 months), p=0.002 |

| miR-19a | High level: 28 Low level: 22 | Thalidomide-based | Non-significance | |

| Ren Y (63) | miR-720 + miR-1246 | Decreased:28 Increased: 8 | Bortezomib plus low-dose dexamethasone | Elevated levels were associated with worse PFS (p=0.0277) |

| Decreased:16 Increased: 8 | Vincristine, adriamycin, and dexamethasone | Elevated levels were associated with worse PFS (p=0.0184) | ||

| Robak P (65) | miR-744-5p | Refractory group: 19 Sensitive group:11 | Bortezomib-based | Distribution difference, p=0.0006; predict refractoriness: OR=0.06, p=0.0146 |

| miR-143-5p | Distribution difference, p=0.0051; predict refractoriness: OR=4.14, p=0.0157 | |||

| Narita D (66) | mir-92a | Newly diagnosed: 10; relapsed and/or refractory: 52 | Bortezomib plus low-dose dexamethasone | Had higher expression in relapsed and/or refractory MM than in newly diagnosed MM, and correlated with chemotherapy response and disease progression |

| Yoshizawa S (67) | miR-92a | Total: 138 | Bortezomib | Only up-regulated after therapy in responders |

| Hao M (68) | miR-214 | Total: 108 | Bisphosphonates | Higher level corelated with extended OS (NR vs 26.0 months, p=0.029) |

| Nowicki M (69) | miR-15a | Total: 42 | Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | Patients with low expression on day 0 had a shorter time to engraftment than those with high expression (11 vs 13 days), p=0.01 |

| Navarro A (70) | miR-20a | Total: 33 | Autologous stem cell transplant | Expression at diagnosis was lower than complete remission, p= 0.009 |

| Jung SH (71) | miR-19a | Good/poor responders: 19/19 | Lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone | Expressed between good responders and poor responders, p=0.073 |

| miR-20a | Between good responders and poor responders, p=0.241 | |||

| Jasielec JK (72) | miR-199 | Total: 30 | Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone | PFS: with decreased risk for progression, HR=0.41; p=0.04 |

| Manier S (73) | let-7e | Total: 156 | Bortezomib plus low-dose dexamethasone, followed by high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant | Low level, PFS: HR 2.01 (95%CI, 1.30-3.11), p=0.002; OS: HR 2.39 (95%CI, 1.09-5.24), p=0.030 |

| miR-125b | Low level, PFS: HR 1.02 (95%CI, 0.70-1.49), p=0.906; OS: HR 1.27 (95%CI, 0.60-2.72), p=0.533 | |||

| miR-15a | Low level, PFS: HR 1.37 (95%CI, 0.94-2.00), p=0.101; OS: HR 2.27 (95%CI, 1.02-5.06), p=0.046 | |||

| miR-19a | Low level, PFS: HR 0.13 (95%CI, 0.02-0.99), p=0.049 | |||

| miR-20a | Low level, PFS: HR 2.31 (95%CI, 1.52-3.53), p<0.001; OS: HR 2.91 (95%CI, 1.29-6.54), p=0.010 | |||

| miR-744 | Low level, PFS: HR 1.32 (95%CI, 0.91-1.93), p=0.144; OS: HR 2.10 (95%CI, 0.97-4.53), p=0.059 | |||

| miR-92a | Low level, PFS: HR 1.39 (95%CI, 0.95-2.02), p=0.089; OS: HR 2.15 (95%CI, 1.00-4.65), p=0.051 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MM, multiple myeloma; NR: not reached; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Strength and Limitations

The main strengths of this meta-analysis are the follows: 1) this is the first time that “cohort study design”, patient “stage or Ig isotype” and “newly diagnosed or untreated” information of MM patients were included in the subgroup analysis, summarizing the possible influencing factors of the current results; 2) it uses extensive but rigorous search strategies to optimize the quality of included literature; 3) it is stricter in assessing the quality of the included literature, providing a more detailed summary of included patients and healthy donors; 4) it structures a comprehensive review of the current understanding of circulating miRNAs in multiple myeloma, including the value of diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy-guiding. The major limitations are the following: 1) due to the insufficiency of miRNA studies included, the pooled diagnostic power of miRNA may be of some deviation, and the results of the subgroup analysis may also be biased to some extent; 2) some miRNAs are also dysregulated in other hematologic diseases; for example, miR-143, miR-144, and miR-199 are also under-expressed in child acute lymphoblastic leukemia, suggesting that circulating miRNAs may not be independent diagnostic biomarkers of MM, but can only be used as auxiliary and discriminatory diagnostic biomarkers (74).

Recommendations

For diagnostic markers, randomized controlled trials are hard to achieve due to the limitations on patient choice and the invasiveness of the gold standard test; many studies have adopted case–control study designs. However, the reproducibility of miRNA-based studies in the diagnosis of MM is conducive to the feasibility of clinical application. Optimizing the flow of miRNA diagnostic tests according to the following suggestions would enable researchers to conduct systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and draw more practical conclusions.

Patient Selection

“newly diagnosed or untreated patient” should be regarded as one of the criteria for the inclusion of diagnostic test, for circulating miRNA profile and level may change due to treatment. Pathological stage or IG isotype information of MM patients should be provided in detail, since the progression and Ig isotype of MM may affect circulating miRNA expression.

Study Design

Case–control study should not be perceived as a valid design for investigating the diagnostic value of miRNAs in MM patients. A cohort study may be a more applicable design initially, owing to the limited source of patients. Randomized controlled trials could be taken into consideration after the diagnostic power has been qualified.

Control Groups

To attenuate selection bias and avoid overestimation of diagnostic value, researchers should consider setting up control groups for suspected cases, individuals with MM precursor state, and patients with other conditions (such as inflammation, cardiovascular disease, or other non-cancerous conditions) separately, rather than just healthy controls. It was reported that about 28.6% of MM patients were diagnosed at the age of 65–74 years, and about 3.5% were under 44 (75). Besides, the incidence of MM is more prevalent in black race than in white, and higher in males than in females (76). Hence, the composition of age, ethnicity and gender of the control group should be consistent with that of the experimental group.

Sample Size

A sufficient sample size should be rigorously calculated in advance and can be achieved through collaboration between specialized institutions.

Specimen and Storage

Based on the long-term storage stability, circulating miRNAs have reliable performance as biomarkers. Both serum and plasma samples can be used to detect circulating miRNAs since there is no significant difference between serum or plasma-based tests. The researchers found that preservation at −20°C barely influenced the total amount of miRNAs for at least 2–4 years, with only slight changes in the concentration of individual miRNAs; in addition, storage at −80°C is even better (77).

Reference Standard

There are two widely used diagnostic criteria for patients with multiple myeloma and MUGS, one from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the other from the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) (78, 79). To avoid ambiguity and bias, researchers should clearly define the reference criteria.

Experimental Flow and Result Interpretation

Strict concealment measures should be observed throughout the study, including grouping, detection, and interpretation of test results. In addition the instruments, reagents, operating procedures, and the cutoff value of the test should be determined before the validation process and be detailed in the paper to avoid subjective bias and to ensure reproducibility. Except for the data on sensitivity, specificity and AUC, the direct presentation of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) data would be of great benefit for future systematic evaluation.

Conclusion

Through the unremitting efforts of researchers, miRNAs have been confirmed to be implicated in many pathophysiological processes of MM; however, the exact regulation mechanism remains to be fully elucidated. Much attention has been given to the diagnostic value of circulating miRNAs in MM over the past decade. This meta-analysis reveals that miR-4254 has the best potential to be a biomarker for MM diagnosis, and miRNA cluster might be a good choice to optimize the utilization. Successfully unraveling the diagnostic value of circulating miRNAs in MM will depend on multicenter large-scale studies with rigorous process design and a broad enrolment in patient and control groups.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study were derived from the included article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JZ designed the study, assessed the quality of the manuscript. YX and PX were responsible for study searching, data extraction and meta-analysis implementation. LZ reviewed the results of each step and resolved any differences in the evaluation opinions of other authors. YX, PX, and LZ co-drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was supported by Youth Foundation of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802075/H2003).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the efforts of researchers and volunteers in investigating the application of miRNAs in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

References

- 1. Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA, van Duin M, Sonneveld P, Mateos MV, et al. Multiple Myeloma. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2017) 3:17046. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kyle R, Larson D, Therneau T, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Cerhan J, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. N Engl J Med (2018) 378:241–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Capp JP, Bataille R. Multiple Myeloma Exemplifies a Model of Cancer Based on Tissue Disruption as the Initiator Event. Front Oncol (2018) 8:355(6). 10.3389/fonc.2018.00355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kyle R, Durie B, Rajkumar S, Landgren O, Blade J, Merlini G, et al. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS) and Smoldering (Asymptomatic) Multiple Myeloma: IMWG Consensus Perspectives Risk Factors for Progression and Guidelines for Monitoring and Management. Leukemia (2010) 24(6):1121–7. 10.1038/leu.2010.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. He Y, Wheatley K, Glasmacher A, Ross H, Djulbegovic B. Early Versus Deferred Treatment for Early Stage Multiple Myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2003) 2003(1):CD004023. 10.1002/14651858.CD004023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Handa H, Murakami Y, Ishihara R, Kimura-Masuda K, Masuda Y. The Role and Function of microRNA in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (2019) 11(11):1738. 10.3390/cancers11111738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Che F, Chen J, Wan C, Huang X. MicroRNA-27 Inhibits Autophagy and Promotes Proliferation of Multiple Myeloma Cells by Targeting the NEDD4/Notch1 Axis. Front Oncol (2020) 10:571914. 10.3389/fonc.2020.571914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8. D’Angelo B, Benedetti E, Cimini A, Giordano A. MicroRNAs: A Puzzling Tool in Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy. Anticancer Res (2016) 36(11):5571–75. 10.21873/anticanres.11142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang L, Cao D, Tang L, Sun C, Hu Y. A Panel of Circulating miRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Screening Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Lab Hematol (2016) 38(6):589–99. 10.1111/ijlh.12560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao S-S, Wang Y-J, Zhang G-X, Zhang W-T. Potential Diagnostic Value of Circulating miRNA for Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. J Bone Oncol (2020) 25:100327. 10.1016/j.jbo.2020.100327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li F, Xu Y, Deng S, Li Z, Zou D, Yi S, et al. MicroRNA-15a/16-1 Cluster Located at Chromosome 13q14 is Down-Regulated But Displays Different Expression Pattern and Prognostic Significance in Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget (2015) 6(35):38270–82. 10.18632/oncotarget.5681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu J, Qiu X, Shen X, Shi W, Wu X, Gu G, et al. miR-202 Expression Concentration and its Clinical Significance in the Serum of Multiple Myeloma Patients. Ann Clin Biochem (2014) 51(Pt 5):543–9. 10.1177/0004563213501155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li J, Zhang M, Wang C. Circulating miRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Multiple Myeloma and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. J Clin Lab Anal (2020) 34(6):e23233. 10.1002/jcla.23233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gupta N, Kumar R, Seth T, Garg B, Sati HC, Sharma A. Clinical Significance of Circulatory microRNA-203 in Serum as Novel Potential Diagnostic Marker for Multiple Myeloma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2019) 145(6):1601–11. 10.1007/s00432-019-02896-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shen X, Ye Y, Qi J, Shi W, Wu X, Ni H, et al. Identification of a Novel microRNA, miR-4449, as a Potential Blood Based Marker in Multiple Myeloma. Clin Chem Lab Med (2017) 55(5):748–54. 10.1515/cclm-2015-1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang Y, Luan Y, Chang H, Chen G. The Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Plasma microRNA-125b-5p in Patients With Multiple Myeloma. Oncol Lett (2018) 16(3):4001–7. 10.3892/ol.2018.9128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qu X, Zhao M, Wu S, Yu W, Xu J, Xu J, et al. Circulating microRNA 483-5p as a Novel Biomarker for Diagnosis Survival Prediction in Multiple Myeloma. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl (2014) 31(10):219. 10.1007/s12032-014-0219-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kubiczkova L, Kryukov F, Slaby O, Dementyeva E, Jarkovsky J, Nekvindova J, et al. Circulating Serum microRNAs as Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Multiple Myeloma and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. Haematologica (2014) 99(3):511–18. 10.3324/haematol.2013.093500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshizawa S, Ohyashiki JH, Ohyashiki M, Umezu T, Suzuki K, Inagaki A, et al. Downregulated Plasma miR-92a Levels Have Clinical Impact on Multiple Myeloma and Related Disorders. Blood Cancer J (2012) 2(1):e53. 10.1038/bcj.2011.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones CI, Zabolotskaya MV, King AJ, Stewart HJS, Horne GA, Chevassut TJ, et al. Identification of Circulating microRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Use in Multiple Myeloma. Br J Cancer (2012) 107(12):1987–96. 10.1038/bjc.2012.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hao M, Zang M, Wendlandt E, Xu Y, An G, Gong D, et al. Low Serum miR-19a Expression as a Novel Poor Prognostic Indicator in Multiple Myeloma. Int J Cancer (2015) 136(8):1835–44. 10.1002/ijc.29199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sevcikova S, Kubiczkova L, Sedlarikova L, Slaby O, Hajek R. Serum miR-29a as a Marker of Multiple Myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma (2013) 54:189–91. 10.3109/10428194.2012.704030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manier S, Boswell E, Sacco A, Maiso P, Banwait R, Aljawai Y, et al. Comparative miRNA Expression Profiling of Circulating Exosomes From MGUS and Smoldering Multiple Myeloma Patients. Blood (2012) 120:3975. 10.1182/blood.V120.21.3975.3975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang ZY, Li YC, Geng CY, Zhou HX, Gao W, Chen WM. Serum Exosomal microRNAs as Novel Biomarkers for Multiple Myeloma. Hematol Oncol (2019) 37(4):409–17. 10.1002/hon.2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved Seed Pairing, Often Flanked by Adenosines, Indicates That Thousands of Human Genes are MicroRNA Targets. Cell (2005) 120(1):15–20. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diehl P, Fricke A, Sander L, Stamm J, Bassler N, Htun N, et al. Microparticles: Major Transport Vehicles for Distinct microRNAs in Circulation. Cardiovasc Res (2012) 93:633–44. 10.1093/cvr/cvs007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Imai Y. Latest Development in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (2020) 12(9):2544. 10.3390/cancers12092544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soley L, Falank C, Reagan MR. MicroRNA Transfer Between Bone Marrow Adipose and Multiple Myeloma Cells. Curr Osteoporos Rep (2017) 15(3):162–70. 10.1007/s11914-017-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grasedieck S, Sorrentino A, Langer C, Buske C, Döhner H, Mertens D, et al. Circulating microRNAs in Hematological Diseases: Principles, Challenges, and Perspectives. Blood (2013) 121:4977–84. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li X, Liu J, Chen M, Gu J, Huang B, Zheng D, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients With Multiple Myeloma: A Real-World Study in China. Cancer Med (2020) 9(21):7896–913. 10.1002/cam4.3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goodman AM, Kim MS, Prasad V. Persistent Challenges With Treating Multiple Myeloma Early. Blood (2020) 137(4):456–8. 10.1182/blood.2020009752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vajen T, Mause SF, Koenen RR. Microvesicles From Platelets: Novel Drivers of Vascular Inflammation. Thromb Haemost (2015) 114(2):228–36. 10.1160/TH14-11-0962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guo M, Li R, Yang L, Zhu Q, Han M, Chen Z, et al. Evaluation of Exosomal miRNAs as Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers for Acute Myocardial Infarction Using Next-Generation Sequencing. Ann Transl Med (2021) 9(3):219. 10.21037/atm-20-2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hulsmans M, Holvoet P. MicroRNA-Containing Microvesicles Regulating Inflammation in Association With Atherosclerotic Disease. Cardiovasc Res (2013) 100(1):7–18. 10.1093/cvr/cvt161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang R, Zhang H, Ding W, Fan Z, Ji B, Ding C, et al. miR-143 Promotes Angiogenesis and Osteoblast Differentiation by Targeting Hdac7. Cell Death Dis (2020) 11:179. 10.1038/s41419-020-2377-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu G, Cheng P, Liu T, Wang Z. BMSC-Derived Exosomal miR-29a Promotes Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol (2020) 8:608521. 10.3389/fcell.2020.608521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gupta N, Kumar R, Seth T, Garg B, Sharma A. Targeting of Stromal Versican by miR-144/199 Inhibits Multiple Myeloma by Downregulating FAK/STAT3 Signalling. RNA Biol (2020) 17(1):98–111. 10.1080/15476286.2019.1669405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ventura A, Young AG, Winslow MM, Lintault L, Meissner A, Erkeland SJ, et al. Targeted Deletion Reveals Essential and Overlapping Functions of the miR-17 Through 92 Family of miRNA Clusters. Cell (2008) 132(5):875–86. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morelli E, Leone E, Cantafio M, Di Martino MT, Amodio N, Biamonte L, et al. Selective Targeting of IRF4 by Synthetic microRNA-125b-5p Mimics Induces Anti-Multiple Myeloma Activity. Vitro Vivo Leukemia (2015) 29(11):2173–83. 10.1038/leu.2015.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murray MY, Rushworth SA, Zaitseva L, Bowles KM, MacEwan DJ. Attenuation of Dexamethasone-Induced Cell Death in Multiple Myeloma is Mediated by miR-125b Expression. Cell Cycle (2013) 12(13):2144–53. 10.4161/cc.25251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hao M, Zhang L, An G, Meng H, Han Y, Xie Z, et al. Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Protect Myeloma Cells From Bortezomib Induced Apoptosis by Suppressing microRNA-15a Expression. Leuk Lymphoma (2011) 52(9):1787–94. 10.3109/10428194.2011.576791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Z, Liu L, Du C, Yu Z, Yang Y, Xu J, et al. Therapeutic Effects of Oligo-Single-Stranded DNA Mimicking of hsa-miR-15a-5p on Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Gene Ther (2020) 27(12):1–9. 10.1038/s41417-020-0161-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wong KY, Liang R, So CC, Jin DY, Costello JF, Chim CS. Epigenetic Silencing of MIR203 in Multiple Myeloma. Br J Haematol (2011) 154(5):569–78. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhao Y, Xie Z, Lin J, Liu P. MiR-144-3p Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Multiple Myeloma by Targeting C-Met. Am J Transl Res (2017) 9(5):2437–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tian F, Wang H, Ma H, Zhong Y, Liao A. mIR−144−3p Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration and Angiogenesis of Multiple Myeloma Cells by Targeting Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2a. Int J Mol Med (2020) 46(3):1155–65. 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bi C, Chung TH, Huang G, Zhou J, Yan J, Ahmann G, et al. Genome-Wide Pharmacologic Unmasking Identifies Tumor Suppressive microRNAs in Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget (2015) 6(28):26508–18. 10.18632/oncotarget.4769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yuan J, Su Z, Gu W, Shen X, Zhao Q, Shi L, et al. MiR-19b and miR-20a Suppress Apoptosis, Promote Proliferation and Induce Tumorigenicity of Multiple Myeloma Cells by Targeting PTEN. Cancer Biomark (2019) 24(3):1–11. 10.3233/CBM-182182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang T, Tao W, Zhang L, Li S. Oncogenic Role of microRNA-20a in Human Multiple Myeloma. OncoTargets Ther (2017) 10:4465–74. 10.2147/OTT.S143612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang Z, Zhou H, Geng C, Gao W, Chen W. Aberrant Expression of Mir-20a in Serum Exosomes of Multiple Myeloma Lead Abnormal Expression of HIF-1 Signaling Pathway Related Proteins. Blood (2020) 136:43. 10.1182/blood-2020-141182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xiao X, Gu Y, Wang G, Chen S. C-Myc, RMRP, and miR-34a-5p Form a Positive-Feedback Loop to Regulate Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis in Multiple Myeloma. Int J Biol Macromol (2019) 122:526–37. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Di Martino MT, Leone E, Amodio N, Foresta U, Lionetti M, Pitari MR, et al. Synthetic miR-34a Mimics as a Novel Therapeutic Agent for Multiple Myeloma: In Vitro and In Vivo Evidence. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18(22):6260–70. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pichiorri F, Suh S-S, Ladetto M, Kuehl M, Palumbo T, Drandi D, et al. MicroRNAs Regulate Critical Genes Associated With Multiple Myeloma Pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105(35):12885–90. 10.1073/pnas.0806202105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lv H, Wu X, Ma G, Sun L, Meng J, Song X, et al. An Integrated Bioinformatical Analysis of Mir−19a Target Genes in Multiple Myeloma. Exp Ther Med (2017) 14(5):4711–20. 10.3892/etm.2017.5173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Frassanito MA, Desantis V, Di Marzo L, Craparotta I, Beltrame L, Marchini S, et al. Bone Marrow Fibroblasts Overexpress miR-27b and miR-214 in Step With Multiple Myeloma Progression, Dependent on Tumour Cell-Derived Exosomes. J Pathol (2019) 247(2):241–53. 10.1002/path.5187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tian Z, Zhao J-J, Lin J, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Investigational Agent MLN9708 Target Tumor Suppressor MicroRNA-33b in Multiple Myeloma Cells. Blood (2011) 118(21):136. 10.1182/blood.V118.21.136.136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shen X, Guo Y, Yu J, Qi J, Shi W, Wu X, et al. miRNA-202 in Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Affects the Growth and Adhesion of Multiple Myeloma Cells by Regulating B Cell-Activating Factor. Clin Exp Med (2016) 16(3):307–16. 10.1007/s10238-015-0355-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saha M, Chen Y, Abdi J, Chang H. Mir-29a Displays in Vitro and in Vivo Anti-Tumor Activity in Multiple Myeloma. Blood (2014) 124:2090. 10.1182/blood.V124.21.2090.2090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yoshizawa S, Umezu T, Ohyashiki J, Iida S, Ohyashiki K. Lower Plasma Mir-92a Levels Predict Shorter Progression-Free Survival In Newly Diagnosed Symptomatic Multiple Myeloma Patients. Blood (2013) 122(21):1879. 10.1182/blood.V122.21.1879.1879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hao M, Zang M, Yu Q, Fei L, Yang W, Feng X, et al. Serum Mir-4254, Mir-19a and Mir-33b Are Potential Markers For Diagnosis and Prognostic Evaluation In Multiple Myeloma. Blood (2013) 122(21):3222. 10.1182/blood.V122.21.3222.3222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hao M, Zang M, Zhao L, Deng S, Xu Y, Qi F, et al. Serum High Expression of miR-214 and miR-135b as Novel Predictor for Myeloma Bone Disease Development and Prognosis. Oncotarget (2016) 7(15):19589–600. 10.18632/oncotarget.7319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Huang J, Yu J, Li J, Liu Y, Zhong R. Circulating microRNA Expression is Associated With Genetic Subtype and Survival of Multiple Myeloma. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl (2012) 29(4):2402–8. 10.1007/s12032-012-0210-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ren Y, Li X, Wang W, He W, Wang J, Wang Y. Expression of Peripheral Blood miRNA-720 and miRNA-1246 Can Be Used as a Predictor for Outcome in Multiple Myeloma Patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk (2017) 17(7):415–23. 10.1016/j.clml.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rocci A, Hofmeister CC, Geyer S, Stiff A, Gambella M, Cascione L, et al. Circulating miRNA Markers Show Promise as New Prognosticators for Multiple Myeloma. Leukemia (2014) 28(9):1922–6. 10.1038/leu.2014.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robak P, Drozdz I, Jarych D, Mikulski D, Weglowska E, Siemieniuk-Rys M, et al. The Value of Serum MicroRNA Expression Signature in Predicting Refractoriness to Bortezomib-Based Therapy in Multiple Myeloma Patients. Cancers (2020) 12(9):2569. 10.3390/cancers12092569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Narita T, Ri M, Kinoshita S, Yoshida T, Totani H, Ashour R, et al. Identification of Circulating Serum microRNAs as Novel Biomarkers Predicting Disease Progression and Sensitivity to Bortezomib Treatment in Multiple Myeloma. Blood (2016) 128(22):4408. 10.1182/blood.V128.22.4408.4408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yoshizawa S, Ohyashiki JH, Ohyashiki M, Umezu T, Suzuki K, Inagaki A, et al. Plasma Mir-92a Levels in Multiple Myeloma Correlate With T-Cell-Derived Mir-92a and Restored in Bortezomib Responder. Blood (2011) 118(21):2871. 10.1182/blood.V118.21.2871.2871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hao M, Zang M, Xu Y, Qin Y, Zhao L, Deng S, et al. Serum High Expression of Micorna-214 Is a Novel Predictor for Myeloma Bone Disease and Poor Prognosis. Blood (2015) 126(23):4186. 10.1182/blood.V126.23.4186.4186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nowicki M, Szemraj J, Wierzbowska A, Misiewicz M, Małachowski R, Pluta A, et al. miRNA-15a, miRNA-16, miRNA-126, miRNA-146a, and miRNA-223 Expressions in Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Their Impact on Engraftment. Eur J Haematol (2018) 100(5):426–35. 10.1111/ejh.13036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Navarro A, Díaz T, Tovar N, Pedrosa F, Tejero R, Cibeira MT, et al. A Serum microRNA Signature Associated With Complete Remission and Progression After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Patients With Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget (2015) 6(3):1874–83. 10.18632/oncotarget.2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jung SH, Lee SE, Lee M, Kim SH, Yim SH, Kim TW, et al. Circulating microRNA Expressions can Predict the Outcome of Lenalidomide Plus Low-Dose Dexamethasone Treatment in Patients With Refractory/Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Haematologica (2017) 102(11):e456–9. 10.3324/haematol.2017.168070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jasielec JK, Chen JL, Rosebeck S, Dytfeld D, Griffith K, Alonge M, et al. Microrna (miRNA) Expression Profiling in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM) Treated With Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone (CRD). Haematologica (2014) 99(S1):366. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Manier S, Liu C-J, Avet-Loiseau H, Park J, Shi J, Campigotto F, et al. Prognostic Role of Circulating Exosomal miRNAs in Multiple Myeloma. Blood (2017) 129:2429–36. 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rashed WM, Hammad AM, Saad AM, Shohdy KS. MicroRNA as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Recommendations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2019) 136:70–8. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, et al. Review of 1027 Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc (2003) 78:21–33. 10.4065/78.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Waxman AJ, Mink PJ, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Weiss BM, Kristinsson SY, et al. Racial Disparities in Incidence and Outcome in Multiple Myeloma: A Population-Based Study. Blood (2010) 116(1):5501–6. 10.1182/blood-2010-07-298760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Grasedieck S, Schöler N, Bommer M, Niess JH, Tumani H, Rouhi A, et al. Impact of Serum Storage Conditions on microRNA Stability. Leukemia (2012) 26(11):2414–6. 10.1038/leu.2012.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kumar SK, Callander NS, Adekola K, Anderson L, Baljevic M, Campagnaro E, et al. Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2020) 18(12):1685–717. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos M-V, et al. International Myeloma Working Group Updated Criteria for the Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma. Lancet Oncol (2014) 15(12):e538–48. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study were derived from the included article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.