Abstract

During space missions, astronauts experience acute and chronic low-dose-rate radiation exposures. Given the clear gap of knowledge regarding such exposures, we assessed the effects acute and chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons and single or fractionated simulated galactic cosmic ray exposure (GCRsim) on behavioral and cognitive performance in mice. In addition, we assessed the effects of an aspirin-containing diet in the presence and absence of chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons. In C3H male mice, there were effects of acute radiation exposure on activity levels in the open field containing objects. In addition, there were radiation-aspirin interactions for effects of chronic radiation exposure on activity levels and measures of anxiety in the open field, and on activity levels in the open field containing objects. There were also detrimental effects of aspirin and chronic radiation exposure on the ability of mice to distinguish the familiar and novel object. Finally, there were effects of acute GCRsim on activity levels in the open field containing objects. Activity levels were lower in GCRsim than sham-irradiated mice. Thus, acute and chronic irradiation to a mixture of neutrons and photons and acute and fractionated GCRsim have differential effects on behavioral and cognitive performance of C3H mice. Within the limitations of our study design, aspirin does not appear to be a suitable countermeasure for effects of chronic exposure to space radiation on cognitive performance.

INTRODUCTION

Galactic cosmic rays (GCR) involve fully ionized atomic nuclei while solar particle events (SPE) include low- to medium-energy protons with a small heavy-ion component. To simulate the space radiation environment, most studies to date have used acute high-dose-rate exposures to single ions (1-6), or multiple ions delivered sequentially, involving, e.g., protons (150 MeV/n, 0.1 Gy) and 56Fe ions (600 MeV/n, 0.5 Gy) (7) or three sequential beam exposures (8), or fractioned doses. Facilities are in place that allow the use of acute and chronic exposure of a mixed field of neutrons and photons for animal studies (9). The unique resource at Colorado State University (CSU; Fort Collins, CO) is now being used to assess the effects of chronic low-dose-rate irradiation to a mixed field of neutrons and photons on the brain (10, 11). While arguably the best analog available for modeling dose rate at this point in time, the extent to which the CSU facility accurately represents the GCR that astronauts are exposed to during space missions is still under debate (12). The Columbia IND Neutron Facility [CINF, Irvington, NY (13)] also allows for comparing the effects of chronic and acute neutron exposure on the brain. This facility includes an accelerator-based neutron irradiator which mimics the neutron energy spectrum from an improvised nuclear device (IND). A mixed beam of atomic and molecular ions of hydrogen and deuterium is accelerated to 5 MeV and used to bombard a thick beryllium target. The energy spectrum of neutrons emitted at 60° to the ion-beam axis closely mimics the Hiroshima spectrum at 1–1.5 km from the epicenter (14). The fields at the Columbia and CSU facilities are not identical. The CINF spectrum is dominated by 0.2–9 MeV neutrons with a linear energy transfer (LET) range between 10 and 200 keV/mm, somewhat broader than the 252Cf fission spectrum at CSU which only reaches an LET of 100 keV/mm (15). However, they have similar dose-averaged LET values (79 keV/mm for CINF and 72 keV/mm for CSU) and can both be used to approximate the high LET (around 100 keV/mm) component of the GCR spectrum (Fig. 1), which is believed to have the highest RBE for many end points (16).

FIG. 1.

LET distributions of the high-LET component of the simulated GCR spectrum, provided at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory (27) with that calculated for the neutron fields used in this work. (Published and modified, with permission, from the following: Norbury JW, Schimmerling W, Slaba TC, Azzam EI, Badavi FF, Baiocco G, et al. Galactic cosmic ray simulation at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory. Life Sci Space Res (Amst) 2016; 8:38-51; and Borak TB, Heilbronn LH, Krumland N, Weil MM. Design and dosimetry of a facility to study health effects following exposures to fission neutrons at low dose rates for long durations. Int J Radiat Biol 2019:1-14. Epub ahead of print.)

Chronic neutron exposure is pertinent as astronauts are exposed to them during space missions; and chronic exposures are particularly relevant as most radiation ground studies to date do not involve chronic exposures. The chronic exposure studies also allow for assessing efficacy of potential space radiation countermeasures. Aspirin has been studied widely to assess its ability to reduce incidence, severity and mortality from cancer, including colorectal cancer, esophageal carcinoma and stomach cancer (17-19). However, caution is warranted in prescribing aspirin to patients who receive radiation therapy and develop thrombocytopenia. While preclinical and clinical beneficial effects of aspirin have been reported in mood disorders, schizophrenia, and risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease [for a review, see (20)], there is increased risk of bleeding that is also pertinent to the brain (21).

Beneficial effects of aspirin on behavioral and cognitive performance have been reported in preclinical studies. Aspirin (2 mg/kg/day) improved hippocampus-dependent cognitive performance in the Barnes and T maze and measures of anxiety in the open field in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model (FAD5X) (22). These effects appeared to involve binding of aspirin to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα), as no beneficial effects of aspirin were seen in FAD5X mice lacking PPARα (22). Aspirin (50 mg/kg/day) reduced stereotypic counts in the open field and modestly affected hyperactivity in the open field after ouabain intracerebral treatment, a model of mania-like features (23). In an AlCl3-induced neurotoxicity mouse model, aspirin (5 or 20 mg/kg/day) improved spatial learning and memory in the water maze, social interactions and social novelty preference, and enhanced contextual fear memory 24 h after training and enhanced extinction of contextual fear (24). However, while aspirin (100 mg/kg/day) prevented behavioral performance in the open field induced by infection with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, it also increased mortality (25). The effects of aspirin in modulating the effects of chronic exposure to space radiation on brain function are not known.

The Galactic Cosmic Ray Simulation (GCRsim) and Mitigation (GSAM) project was designed to provide a delivery scheme of low- and high-LET particles to best simulate 600–900-day Mars missions using animal models (26, 27). This delivery scheme allows for assessing whether fractionated exposures have the same effects as chronic low-dose-rate exposures. As part of this project, mice were irradiated with simulated GCR split into 19 fractions delivered over 4 weeks or received an acute exposure of the same total dose.

In the current study, we assessed the effects of acute and chronic irradiation to a mixed field of neutrons and photons and single or fractionated simulated galactic cosmic ray exposure on behavioral and cognitive performance in mice. In addition, we assessed the effects of an aspirin-containing diet in the presence and absence of chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, Irradiations, Study Design and Home Cage Monitoring

C3H/HeNCrL (C3H) male mice and BALB/cAnNCrl (BALB/c) female mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) at 10–11 weeks of age. All mice were group housed prior and during the behavioral studies. The opportunistic current study took advantage of the availability of irradiated and sham-irradiated mice from three radiation carcinogenesis experiments, described below in detail. The choice of strain and sex of the mice was based on the carcinogenesis study and related susceptibility of the mice to develop tumors later in life. The mice were behaviorally tested for performance in the open field, object recognition, and contextual and cued fear conditioning.

Experiment 1. Acute exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons.

Ten-week-old BALB/c female mice and 10-week-old C3H male mice received a single dose of 0.4 Gy (0.33 Gy neutrons and 0.07 Gy concomitant photons), delivered over 25 min, or sham irradiation (BALB/c: 10/23/18; n = 10 sham-irradiated mice; n = 9 irradiated mice; C3H: 12/4/18; n = 16 irradiated mice, n = 10 sham-irradiated mice) at the Columbia University’s Radiological Research Accelerator Facility (RARAF). Mice were placed in modified 50-ml tubes, on a Ferris wheel rotating around a beryllium target and flipped front to back half-way through the irradiation, to ensure a spatially uniform dose. A mixed 5-MeV proton/deuteron beam (10 mA) was used to generate neutrons on the target. Neutron and photon dosimetry were performed on the day of irradiation using a tissue-equivalent ionization chamber and GM counter, respectively. Details of the irradiation platform and dosimetry procedures are provided elsewhere (13). In Fig. 1, the LET distribution for the high-LET component of simulated GCR at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Upton, NY) (27, 28) is compared with those calculated based on spectroscopic measurements (14, 15) for the fields used in this study. Both sources are “contaminated” with similar amounts of concomitant photons (17–20%). The mice were tested for exploratory behavior in the open field (BALB/c: n = 10 sham, n = 12 irradiated mice; C3H: n = 10 sham, n = 16 irradiated mice) and contextual and cued fear conditioning (BALB/c: n = 10 sham, n = 9 irradiated mice); C3H: n = 9 sham, n = 9 irradiated mice) about 400 days postirradiation or sham irradiation (10/28/19–11/7/19).

Experiment 2. Chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons.

Ten-week-old C3H male mice received mixed-field irradiation, i.e., neutrons and photons (6/4/18–12/21/18: 1 mGy/day; 1/15/19–3/18/19: 1 mGy/day; 3/18/19–9/18/19: 0.75 mGy/day), for a cumulative dose of 0.4 Gy by a source of 252Cf to simulate the chronic, high-LET, low-dose-rate irradiation that will be experienced by spaceflight crew beyond low Earth orbit. The 252Cf source (1.6 GBq, 80 mg, delivered on 3/17/17 and placed in a panoramic irradiator (Model 149; JL Shepherd & Associates, San Fernando, CA) was elevated 130 cm above the floor during irradiation. The cages containing the mice were placed in vertical racks located in a circle having a radius of 180 cm from the source. The mixed radiation field consisted of neutrons and photons emitted directly from the source as well as secondary particles scattered from the floor and walls of the facility. Tissue-equivalent proportional counters were used to characterize the neutron component throughout the room and a miniature GM counter was used to characterize the distribution of photons (15). Further details about the continuous radiation exposure for most of the day and the effect of scattering are provided elsewhere (15).

Mice received standard chow (Envigo/Teklad 2918, Madison, WI) or aspirin in standard chow (Envigo/Teklad 2018) generated by Bio-Serv® (Flemington, NJ) (153 mg of aspirin per kg of chow) starting at the beginning of irradiation. For a 30-g mouse consuming 4.0 g of chow per day this corresponds to an aspirin intake of 100 mg/day for a 60-kg human based on body surface area.

The mice were tested for open field and object recognition (n = 16 mice per radiation condition/diet) and contextual and cued fear conditioning (n = 9 mice per radiation condition/diet) approximately 600 days after the start of irradiation or sham irradiation (10/28/19–11/7/19).

Experiment 3. GCRsim study.

GCRsim consisted of 13 energies each for protons and helium, and five heavy ions: C, O, Si, Ti, Fe. The beam selection was based on a study of the space radiation environment inside an astronaut’s body versus the capability of the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory facility (at BNL) to simulate this radiation field in terms of LET spectrum and particle abundance using a discrete set of beams. In experiment 3, there were three experimental groups: 1. 10-week-old C3H male mice were sham irradiated and tested for open field and object recognition (n = 7 mice) and contextual and cued fear conditioning (n = 7 mice). (open field and object recognition and contextual and cued fear conditioning: n = 7 mice); 2. 10-week-old C3H male mice received 0.4 Gy GCRsim in a single fraction over approximately 2 h on 10/22/18 and tested for performance in the open field and object recognition (n = 16 mice) and contextual and cued fear conditioning (n = 12 mice/radiation condition); and 3. 12-week-old C3H male mice received 0.4 Gy GCRsim delivered in 19 fractions over 1 month, between 10/8/18 and 11/2/18, and tested for performance in the open field and object recognition (n = 16 mice) and contextual and cued fear conditioning (n = 12 mice). All animals tested for contextual and cued fear conditioning were tested previously for performance in the open field and object recognition.

After irradiation, the mice were housed at the animal facility on the CSU Foothill Campus. The mice in experiment 3 were tested approximately 460 days postirradiation or sham irradiation ((10/28/19-11/7/19). All mice were kept under a constant 12:12 h light-dark schedule, and water and food (Envigo/Teklad 2918 Irradiated Rodent Diet) were provided ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at CSU and were in compliance with all Federal regulations.

Behavioral and Cognitive Testing

All behavioral and cognitive testing was conducted at CSU by experimenters who were blinded to radiation dose. Each mouse was tested separately over six consecutive testing days. Starting on day 1, exploratory activity and measures of anxiety were assessed in the open field for two days (day 1 and day 2). The mice were tested for novel object recognition during the two subsequent days (day 3 and day 4). The following two days, mice were tested for contextual and cued fear learning and memory. Body weights were recorded the following week.

Open Field and Novel Object Recognition

The open field was used to assess measures of anxiety, locomotor and exploratory behavior. Mice were singly placed in a lit (average: 4.2 lux) white plastic arena (40.64 × 40.64 cm) (TAP Plastics, Portland, Oregon) for 5-min trials, once each day for two consecutive days. Arenas were cleaned with 0.5% acetic acid between each trial. Movement of the mice and durations spent in the center of the arena (center 20-cm square area) were recorded and analyzed using Viewer video tracking software (Biobserve GmbH, Bonn, Germany). After habituation to the arena for two days, which requires hippocampal function (29), novel object recognition was assessed by placing two identical objects 10 cm apart in the arena on the third day, then replacing one object with a novel object on the fourth day. Trials on the third and fourth days were 15 min each. Videos recorded on day 4 were viewed by experimenters who hand-scored durations of time spent exploring each object. Time spent exploring the novel object versus the familiar object on day 4, expressed as a percentage of the total object exploration time in the trial, was used to determine object recognition memory.

Fear Conditioning

Contextual and cued fear conditioning were used to assess hippocampus-dependent contextual associative memory and hippocampus-independent cued associative memory (30) using near-infrared (NIR) video and automated analysis, and Video Freeze® automated scoring software (Med Associates Inc.®, St. Albans, VT). In the fear conditioning tests, mice learn to associate an environmental context or cue (tone, conditioned stimulus, CS) with a mild foot shock (unconditioned stimulus, US). Upon re-exposure to the training context, or a new environment in which the mice are exposed to a tone that was present during training, associative learning is assessed based on freezing behavior, characterized by absence of all movement with the exception of respiration. On the training day, the mice were individually placed inside a white LED lit (100 lux) fear conditioning chamber with a metal grid floor and allowed to habituate for a 90-s baseline period. This was followed by an 80-dB, 2,800-Hz tone (CS or cue) lasting for 30 s and co-terminating with a 2-s, 0.7-mA foot shock (US) at 120 s. Five tone-shock pairings were used, with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 90 s. Measurements of average motion (cm/s) and percentage of time freezing were analyzed during the baseline period (prior to the first tone), and during each subsequent ISI and CS (tone/cue) to assess acquisition of fear memory. Chambers were cleaned between trials with a 0.5% acetic acid solution. The next day, the mice were placed back into the same context as used on the training day, for a single 5-min trial, and freezing behavior was measured in the absence of either tones or shocks to assess contextual associative memory. At 3 h later, the mice were placed into a novel context, containing a smooth white plastic covering over the wire grid floor, a “tented” black plastic ceiling, and scented with hidden vanilla extract-soaked nestlets. The chambers were cleaned between trials with a 10% isopropanol solution. Each trial consisted of a 90-s baseline, then a 180-s 80-dB, 2,800-Hz tone, and freezing behavior was analyzed as an indicator of cued associative memory.

Statistical Analyses

All data are shown as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS™ version 22 (Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) software packages. The data from the training day were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with radiation as between-group factor, followed up by post hoc tests when appropriate. Performance over multiple trials was analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA. If violation of sphericity occurred, indicating that the variances of the differences between all combinations of the groups were not equal (Mauchly’s test), Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were used. When appropriate, Bonferroni’s post hoc, Dunnett’s, and paired t tests were used. All figures were generated using GraphPad Prism software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Experiment 1. Acute Exposure to a Mixed Field of Neutrons and Photons

BALB/c mice.

There was no effect of acute exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons on body weights in BALB/c mice (Supplementary Fig. S1A; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). In addition, there were no significant effects of acute radiation exposure on distance moved on days 1 and 2 in the open field (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Over the course of the two days in the open field, sham-irradiated BALB/c mice spent significantly less time in the center of the arena on day 2 than day 1 [t(8) = 3.241, P = 0.012, Supplementary Fig. S1C]. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the time spent in the center of the open field on days 1 and 2 in irradiated BALB/c mice although the pattern appeared to be similar to that observed in sham-irradiated BALB/c mice (Supplementary Fig. S1C). There was no effect of acute irradiation on the percentage time the mice spent exploring the familiar and novel objects (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

Fear learning, assessed as the percentage freezing time between the inter-stimulus intervals (ISIs), was not affected by acute irradiation (Supplementary Fig. S1E; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). Acute irradiation did not affect contextual (Supplementary Fig. S1F) or cued (Supplementary Fig. S1G) fear memory.

C3H mice.

There was no effect of acute exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons on body weights in C3H mice (Supplementary Fig. S2A; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). There were no significant effects of acute irradiation on distance moved on days 1 and 2 in the open field (Supplementary Fig. S2B) or time spent in the center of the open field (Supplementary Fig. S2C). During the trials in the open field containing objects, mice that received acute irradiation moved more on day 2 than day 1 [t(15) = −3.564, P = 0.003, Fig. 2A]. This was not seen in sham-irradiated mice (Fig. 2A). Both sham-irradiated and irradiated mice spent more time exploring the familiar than the novel object but there was no effect of acute radiation exposure (Supplementary Fig. S2D).

FIG. 2.

Effects of acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on distance moved in the open field containing objects (panel A) and on contextual fear memory (panel B) of C3H mice. *P = 0.003; #P = 0.089.

There was no effect of acute radiation exposure on fear learning (Supplementary Fig. S2E; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). There was a trend towards reduced contextual fear memory in mice that received acute irradiation but it did not reach significance [F(16) = 3.278, P = 0.089, Fig. 2B]. In the cued fear memory test, there was a significant increase in freezing during the tone as compared to what was seen during the pre-tone period [F(1, 16) = 26.950, P < 0.01] but there was no effect of acute radiation exposure on cued fear memory (Supplementary Fig. S2F).

Experiment 2. Chronic Exposure to a Mixed Field of Neutrons and Photons

There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons or aspirin on body weights in C3H mice (Supplementary Fig. S3A; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1).

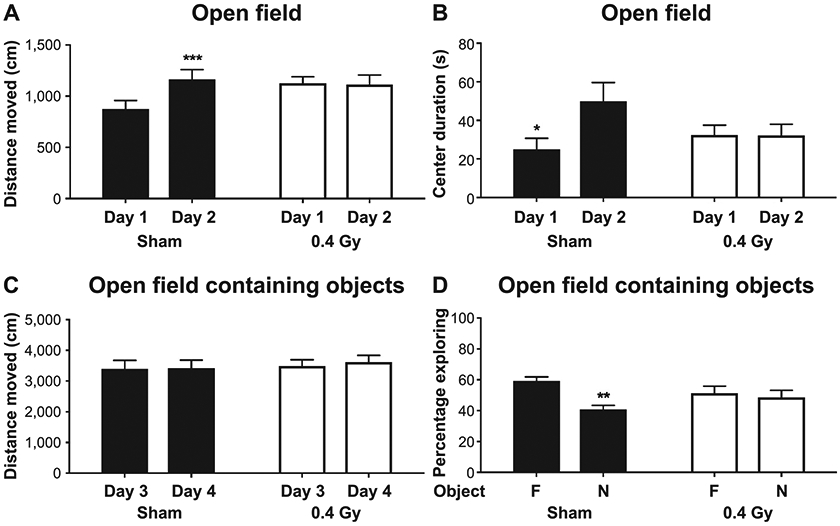

When activity levels in the open field were analyzed, there was a radiation-aspirin interaction (distance moved: F(1, 60) = 4.371, P = 0.041). Sham-irradiated C3H mice on a standard lab chow diet moved more on day 2 than day 1 [t(15) = −4.300, P = 0.001, Fig. 3A]. No difference in activity on days 1 and 2 was seen in irradiated C3H mice on a standard lab chow diet (Fig. 3A), and 0.4 Gy irradiated C3H mice on an aspirin-containing diet moved less on day 2 than day 1 [t(15) = 2.505, P = 0.024, Supplementary Fig. S3B].

FIG. 3.

Effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons in the open field and object recognition tests. Panel A: Sham-irradiated mice on a standard lab chow diet moved more on day 2 than day 1. ***P = 0.001. Panel B: Sham-irradiated mice on a standard chow spent more time in the center of the open field on day 2 than day 1. *P < 0.05. Panel C: Chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons in the open field containing objects did not affect the activity of mice on a standard chow. Panel D: Sham-irradiated mice on a standard chow explored the familiar object more than the novel object. This was not seen in irradiated mice on a standard chow. **P = 0.003.

For time spent in the more anxiety-provoking center of the open field, there was also a radiation-aspirin interaction [F(1, 60) = 6.915, P = 0.011]. When only time spent in the center of the open field on day 1 was analyzed, there was also a radiation-diet interaction [F(3, 60) = 3.593, P = 0.019]. Sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing diet spent more time in the center than sham-irradiated mice fed standard chow (P = 0.024, Tukey’s, Supplementary Fig. S3C; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). Within the group of mice fed aspirin-containing chow, sham-irradiated mice spent more time in the center than irradiated mice (P = 0.039, Tukey’s, Supplementary Fig. S3C). Sham-irradiated mice on a standard lab chow diet spent more time in the center of the open field on day 2 than day 1 [t(15) = −2.532, P = 0.023, Fig. 3B]. In contrast, there was no difference in time spent in the center of the open field on days 1 and 2 in irradiated mice on a standard diet (Fig. 3B) or sham-irradiated and irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing diet (Supplementary Fig. S3C).

When activity levels in the open field containing objects was analyzed, there was also a radiation-aspirin interaction [F(3, 60) = 3.568, P = 0.019]. Sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing diet moved more than sham-irradiated mice on standard chow (P = 0.012, vs. sham-irradiated and standard chow, Dunnett’s, not shown). There was no effect of radiation on activity levels in the open field containing objects in mice on a standard diet (Fig. 3C) or mice on an aspirin-containing diet (Supplementary Fig. S3D; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1).

In the novel object recognition test, sham-irradiated [t(15) = 3.535, P = 0.003] mice on standard chow preferentially explored the familiar object over the novel object (Fig. 3D), suggesting the ability to distinguish the two objects and neophobia. Neophobia, involving persistent and irrational fear of novel objects, which likely involves the amygdala, is a measure distinct from the time spent in the center of the open field, which is a measure of anxiety more related to physiological anticipation of a threat (31). In contrast, no preference for either object was observed in irradiated mice receiving standard chow (Fig. 3D) or sham-irradiated or irradiated mice receiving an aspirin-containing diet (Supplementary Fig. S3E; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1).

During fear learning, there were no effects of radiation or aspirin on activity during the baseline period prior to the first tone or in response to the shocks (Supplementary Fig. S3F; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). There were no effects of radiation on fear learning or contextual or cued fear memory (Supplementary Fig. S3G and H).

Experiment 3. GCRsim Study

There was no effect of acute or fractionated GCRsim on body weights in C3H mice (Supplementary Fig. S4A; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1). There were no effects of acute or fractionated GCRsim on distance moved (Supplementary Fig. S4B) or time spent in the center (Supplementary Fig. S4C) of the open field. However, there was an effect of radiation on activity levels in the open field containing objects [F(2, 39) = 11.942, P < 0.001, Fig. 4A]. Mice that received acute GCRsim moved less than sham-irradiated mice (P = 0.003 vs. sham-irradiated, Dunnett’s).

FIG. 4.

Effects of acute and fractionated GCRsim on distance moved in the open field containing objects (panel A), percentage time exploring the familiar and novel objects (panel B) and fear learning (panel C). Panel A: Mice exposed to acute GCRsim moved less than sham-irradiated mice *P = 0.003. Panel B: Animals that received acute GCRsim preferred the familiar object over the novel object. ***P < 0.001. Panel C: There was a trend towards reduced fear learning in mice that received fractionated versus acute GCRsim. #P = 0.078.

In the novel object recognition test, mice that received acute irradiation [t(15) = 5.148, P < 0.001] preferentially explored the familiar object over the novel object and a trend toward such an effect was observed in mice that received fractionated GCRsim [t(15) = 2.105, P = 0.053, Fig. 4B].

During fear learning, there was a trend towards an effect of radiation on the percentage freezing between the tone-shock periods (ISIs) [F(2, 28) = 2.652, P = 0.088], with a trend towards lower fear learning in mice that received fractionated GCRsim than acute GCRsim (P = 0.078, Tukey’s, Fig. 4C). There were no effects of acute or fractionated GCRsim on contextual (Supplementary Fig. S4D; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00228.1.S1) or cued (Supplementary Fig. S4E) fear memory.

DISCUSSION

This study shows the following effects of space radiation in C3H male mice:

Effects of acute irradiation on activity levels in the open field containing objects with higher activity levels on day 2 than day 1 and a trend towards reduced contextual fear memory.

Effects of acute GCRsim on activity levels in the open field containing objects, with lower activity levels in GCRsim than sham-irradiated mice.

Radiation-aspirin interactions for effects of chronic irradiation on activity levels and measures of anxiety in the open field in C3H mice. The differences observed in distance moved and time spent in the center on days 1 and 2 in sham-irradiated mice on standard chow were not seen in sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing diet or irradiated mice on either diet.

A radiation-aspirin interaction for effects of chronic irradiation on activity levels in the open field containing objects, with higher activity levels in sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing diet than those on a standard chow. This effect of aspirin was not observed in irradiated mice.

Detrimental effects of aspirin and chronic irradiation in the absence and presence of aspirin on the ability of mice to distinguish the familiar and novel object.

Table 1 summarizes the effects of acute and chronic irradiation on behavioral and cognitive performance in C3H mice on a standard diet.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the Behavioral and Cognitive Data

| Experiment | Data |

|---|---|

| 1. Acute exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons | Irradiated C3H mice moved more in the open field containing objects on day 2 than day 1; this was not observed in sham-irradiated mice. There was a trend towards reduced contextual fear memory of C3H mice after irradiation. |

| 2. Chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons | Sham-irradiated C3H mice on a standard lab chow diet moved more on day 2 than day 1; this was not observed in irradiated mice. Sham-irradiated C3H mice on a standard lab chow diet spent more time in the center of the open field on day 2 than day 1; this was not observed in irradiated mice on a standard diet. In the novel object recognition test, sham-irradiated C3H mice on a standard chow preferentially explored the familiar object over the novel object; no preference was observed in irradiated mice receiving standard chow. |

| 3. GCRsim study | C3H mice that received acute GCRsim moved less than sham-irradiated mice. In the novel object recognition test, C3H mice that received acute irradiation preferentially explored the familiar object over the novel object; a trend toward such an effect was observed in mice that received fractionated GCRsim. During fear learning, there was a trend towards lower fear learning in C3H mice that received fractionated GCRsim than in those that received acute GCRsim. |

An important question in simulating space radiation exposures is whether acute or chronic irradiations might be more difficult for the brain to deal with. The ability of the mice to distinguish between the familiar and novel object was impaired after chronic, but not acute irradiation to a mixture of neutrons and photons. The detrimental effects of chronic irradiation on object recognition in the current study are consistent with those seen in C57BL/6J mice at 6-month postirradiation to a mixture of neutrons and photons (18 cGy) in the same facility in a previously reported study (11).

On the other hand, while there was a trend towards reduced contextual fear memory after acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons, this was not seen after chronic exposure. In contrast, a subtle but significant decrease in contextual fear memory was seen 24 h after training in C57BL/6J mice following 6 months of exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons (18 cGy) (11). Differences in the age and strain of the mice, length and dose of chronic exposure, and fear conditioning training paradigm might have contributed to these divergent findings. These data suggest that whether acute or chronic radiation exposure might have more profound effects may depend on the cognitive measure assessed and may be different for novelty detection than for emotional memory. This highlights the importance of including distinct cognitive measures in assessing effects of space radiation on the brain. The effects of chronic irradiation are of great concern regarding CNS risk of astronauts during multiple or longer space missions, including a 2–3-year Mars mission. We recognize that a limitation of this experimental design is that after acute exposures, there might have been transient effects on the brain that were not detected at later follow-up times. In addition, we recognize that effects of aging on behavioral and cognitive performance might have further masked the effects of radiation exposure.

Aspirin did not mitigate or prevent the effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on the ability to distinguish the familiar and novel objects. In addition, aspirin impaired the ability of the mice to distinguish the familiar and novel objects in sham-irradiated mice. We recognize the limitation that in most studies, including the current study, only one dose of aspirin is being tested and that the administration routes (e.g., in the chow or drinking water) also differ among studies. Thus, although in this study aspirin at 170 mg/kg administered via the chow was not beneficial, we cannot exclude the possibility that a lower or higher dose might have shown beneficial effects. Nevertheless, these data suggest that while aspirin had beneficial effects on cognitive performance in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model (FAD5X) (22), a preclinical model of mania-like features (23), and a neurotoxicity model (24), aspirin might not be a suitable countermeasure for effects of chronic exposure to space radiation on cognitive performance.

In the current study, we also compared the effects of acute and fractionated GCRsim on behavioral and cognitive performance. Mice that received acute GCRsim moved less in the open field containing objects than sham-irradiated mice, which was not observed in mice that received fractionated GCRsim. On the contrary, fractionated GCRsim appeared to negatively affect the ability of mice to distinguish between the familiar and novel objects and to learn conditioned fear, compared to acute GCRsim. These data suggest that whether acute and fractionated GCRsim has more profound effects might depend on the behavioral or cognitive measure assessed. Together with the differential effects of acute and chronic radiation exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on distinct cognitive measures, these data highlight the complexity of CNS risk assessment after space radiation exposure.

In summary, acute and chronic radiation exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons and acute and fractionated GCRsim have differential effects on behavioral and cognitive performance of C3H mice. In addition, within the limitations of our study design, aspirin does not appear to be a suitable countermeasure for effects of chronic exposure to space radiation on cognitive performance. Increased efforts are warranted to assess the efficacy of other countermeasures to address the detrimental effects of chronic space radiation exposure.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. There were no effects of acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on body weights (panel A) or distance moved of BALB/c mice in the open field (panel B). There were effects of acute exposure of a mixture of neutrons and photons on time BALB/c mice spent in the center of the open field (panel C). Sham-irradiated BALB/c mice spent less time in the center of the open field on day 2 than day 1. *P = 0.012. There were no effects of acute exposure on the percentage time exploring the familiar and novel objects (panel D), fear learning (panel E), contextual fear memory (panel F) or cued fear memory (panel G) of BALB/c female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Fig. S2. There were no effects of acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on body weights (panel A), distance moved in the open field (panel B), time spent in the center of the open field (panel C), percentage time exploring the familiar and novel objects (panel D), fear learning (panel E) or cued fear memory (panel F). Both groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.

Fig. S3. There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons or aspirin on body weights (panel A). Irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing show diet moved less on day 2 than day 1 (panel B). *P < 0.05. Within the group of mice fed an aspirin-containing chow, sham-irradiated mice spent more time in the center than irradiated mice (panel C). *P < 0.05 (Tukey’s). Sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing chow diet spent more time in the center of the open field than sham-irradiated mice on standard chow (data not shown). There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on activity levels in the open field containing objects (panel D). Sham-irradiated and irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing chow did not show any preference for exploring the familiar or novel object (panel E). There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on fear learning (panel F), contextual fear memory (panel G) or cued fear memory (panel H). All groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.

Fig. S4. There were no effects of acute or fractionated GCRsim on body weights (panel A), distance moved in the open field (panel B), time spent in the center of the open field (panel C), contextual fear memory (panel D) or cued fear memory (panel E). All groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NASA NSCOR grant no. NNX15AK13G. The Columbia IND Neutron Facility (CINF) is partially funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), grant no. U19 AI067773. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAID, the National Institutes of Health or NASA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Impey S, Pelz C, Tafessu A, Marzulla T, Turker MS, Raber J. Proton irradiation induces persistent and tissue-specific DNA methylation changes in the left ventricle and hippocampus. BMC Genomics 2016; 17:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellone J, Hartman R, Vlkolinsky R. The effects of low doses of proton, iron, or silicon radiation on spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Radiat Res 2014; 55:i95–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raber J, Marzulla T, Kronenberg A, Turker MS. (16)Oxygen irradiation enhances cued fear memory in B6D2F1 mice. Life Sci Space Res 2015; 7:61–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabin BM, Poulose SM, Carrihill-Knoll KL, Ramirez F, Bielinski DF, Heroux N, et al. Acute effects of exposure to (56)Fe and (16)O particles on learning and memory. Radiat Res 2015; 184:143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweet TB, Panda N, Hein AM, Das SL, Hurley SD, Olschowka JA, et al. Central nervous system effects of whole-body proton irradiation. Radiat Res 2014; 182:18–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherry JD, Liu B, Frost JL, Lemere CA, Williams JP, Olschowka JA, et al. Galactic cosmic radiation leads to cognitive impairment and increased a(beta) plaque accumulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2012; 7:e53275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raber J, Allen AR, Sharma S, Allen B, Rosi S, Olsen RH, et al. Effects of proton and combined proton and (56)Fe irradiation on the hippocampus. Radiat Res 2015; 184:586–94.26579941 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raber J, Yamazaki J, Torres ERS, Kirchoff N, Stagaman K, Sharpton T, et al. Combined effects of three high energy charged particle beams important for space flight on brain, behavioral and cognitive endpoints in B6D2F1 female and male mice. Front Physiol 2019; 10:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braby LA, Raber J, Chang PY, Dinges DF, Goodhead DT, Herr D, et al. Report No. 183 – Radiation exposure in space and the potential for central nervous system effects: Phase II. NCRP SC 1-24P2 Report. Bethesda, MD: National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez RE, Younger S, Bertheau E, Fallgren CM, Weil MM, Raber J. Effects of chronic neutron exposure on behavioral and cognitive performance in mice. Behav Brain Res 2019; 379:112377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acharya MM, Baulch JE, Klein PM, Baddour AAD, Apodaca LA, Kramar EA, et al. New concerns for neurocognitive function during deep space exposures to chronic, low dose-rate, neutron radiation. eNeuro 2019; 6:ENEURO.0094–19.2019. Erratum in: eNeuro. 2019; 6: ENEURO.0367-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limoli CL, Britten R, Baulch J, Borak T. Response to the commentary from Bevelacqua et al. eNeuro 2020; 7:ENEURO.0439–19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Randers-Pehrson G, Turner HC, Marino SA, Geard CR, Brenner DJ, et al. Accelerator-based biological irradiation facility simulating neutron exposure from an improvised nuclear device. Radiat Res 2015; 184:404–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Randers-Pehrson G, Marino SA, Garty G, Harken A, Brenner DJ. Broad energy range neutron spectroscopy using a liquid scintillator and a proportional counter: Application to a neutron spectrum similar to that from an improvised nuclear device. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 2015; 794:234–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borak TB, Heilbronn LH, Krumland N, Weil MM. Design and dosimetry of a facility to study health effects following exposures to fission neutrons at low dose rates for long durations. Int J Radiat Biol 2019; 1–4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall E, Giacca A. Radiobiology for the radiologist. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2012. p. 546. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gash KJ, Chambers AC, Cotton DE, Williams AC, Thomas MG. Potentiating the effects of radiotherapy in rectal cancer: the role of aspirin, statins and metformin as adjuncts to therapy. Br J Cancer 2017; 117:210–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nan H, Hutter CM, Lin Y, Jacobs EJ, Ulrich CM, White E, et al. Association of aspirin and NSAID use with risk of colorectal cancer according to genetic variants. JAMA 2015; 313:1133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drew DA, Cao Y, Chan AT. Aspirin and colorectal cancer: the promise of precision chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer 2016; 16:173–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berk M, Dean O, Drexhage H, McNeil JJ, Moylan S, O’Neil A, et al. Aspirin: a review of its neurobiological properties and therapeutic potential for mental illness. BMC Med 2013; 11:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WY, Saver JL, Wu YL, Lin CJ, Lee M, Ovbiagele B. Frequency of intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose aspirin in individuals without symptomatic cardiovascular disease; a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2019; 76:906–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel D, Roy A, Kundu M, Jana M, Luan CH, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Aspirin binds to PPARa to stimulate hippocampal plasticity and protect memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:E7408–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, An LT, Qiu Y, Shan XX, Zhao WL, Zhao JP, et al. Effects of aspirin in rats with ouabain intracerebraltreatment-possible involvement of inflammatory modulation? Front Psychiatry 2019; 10:497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizwan S, Idrees A, Ashraf M, Ahmed T. Memory-enhancing effect of aspirin is mediated through opioid system modulation in an AlCl3-induced neurotoxicity mouse model. Exp Ther Med 2016; 11:1961–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silvero-Isidre A, Morinigo-Guayuan S, Meza-Ojeda A, Mongelos-Cardozo M, Centurion-Wenninger C, Figueredo-Thiel S, et al. Protective effect of aspirin treatment on mouse behavior in the acute phase of experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol Res 2018; 117:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slaba T Galactic Cosmic Ray Simulator and Mitigation Project. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (https://go.nasa.gov/3sDRqcz) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slaba TC, Blattnig SR, Norbury JW, Rusek A, La Tessa C. Reference field specification and preliminary beam selection strategy for accelerator-based GCR stimulation. Life Sci Space Res 2016; 8:52–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simonsen LC, Slaba TC, Guida P, Rusek A. NASA’s first ground-based galactic cosmic ray simulator: Enabling a new era in space radiobiology research. PLoS Biol 2020; 18:e3000669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolivar VJ, Caldarone BJ, Reilly AA, Flaherty L. Habituation of activity in an open field: A survey of inbred strains and F1 hybrids. Behav Genet 2000; 30:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anagnostaras SG, Wood SC, Shuman T, Cai DJ, Leduc AD, Zurn KR, et al. Automated assessment of pavlovian conditioned freezing and shock reactivity in mice using the video freeze system. Front Behav Neurosci 2010; 4:s1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarowar T, Grabrucker S, Boeckers TM, Grabrucker AM. Object phobia and altered RhoA signaling in amygdala of mice lacking RICH2. Front Mol Neurosci 2017; 10:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. There were no effects of acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on body weights (panel A) or distance moved of BALB/c mice in the open field (panel B). There were effects of acute exposure of a mixture of neutrons and photons on time BALB/c mice spent in the center of the open field (panel C). Sham-irradiated BALB/c mice spent less time in the center of the open field on day 2 than day 1. *P = 0.012. There were no effects of acute exposure on the percentage time exploring the familiar and novel objects (panel D), fear learning (panel E), contextual fear memory (panel F) or cued fear memory (panel G) of BALB/c female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Fig. S2. There were no effects of acute exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on body weights (panel A), distance moved in the open field (panel B), time spent in the center of the open field (panel C), percentage time exploring the familiar and novel objects (panel D), fear learning (panel E) or cued fear memory (panel F). Both groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.

Fig. S3. There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons or aspirin on body weights (panel A). Irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing show diet moved less on day 2 than day 1 (panel B). *P < 0.05. Within the group of mice fed an aspirin-containing chow, sham-irradiated mice spent more time in the center than irradiated mice (panel C). *P < 0.05 (Tukey’s). Sham-irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing chow diet spent more time in the center of the open field than sham-irradiated mice on standard chow (data not shown). There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on activity levels in the open field containing objects (panel D). Sham-irradiated and irradiated mice on an aspirin-containing chow did not show any preference for exploring the familiar or novel object (panel E). There were no effects of chronic exposure to a mixture of neutrons and photons on fear learning (panel F), contextual fear memory (panel G) or cued fear memory (panel H). All groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.

Fig. S4. There were no effects of acute or fractionated GCRsim on body weights (panel A), distance moved in the open field (panel B), time spent in the center of the open field (panel C), contextual fear memory (panel D) or cued fear memory (panel E). All groups showed cued fear memory. Effect of tone: *P < 0.05.