Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Few studies have rigorously examined the magnitude of changes in well-being after a transition into sustained and substantial caregiving, especially in population-based studies, compared with matched noncaregiving controls.

Design:

We identified individuals from a national epidemiological investigation who transitioned into caregiving over a 10-13 year follow up and provided continuous in-home care for at least 18 months and at least five hours per week. Individuals who did not become caregivers were individually matched with caregivers on age, sex, race, education, marital status, self-rated health, and history of cardiovascular disease at baseline. Both groups were assessed at baseline and follow-up.

Setting:

REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Participants:

251 incident caregivers, and 251 matched controls.

Measurements:

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), 10-Item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D), and SF-12 Quality of Life Mental (MCS) and Physical (PCS) component scores.

Results:

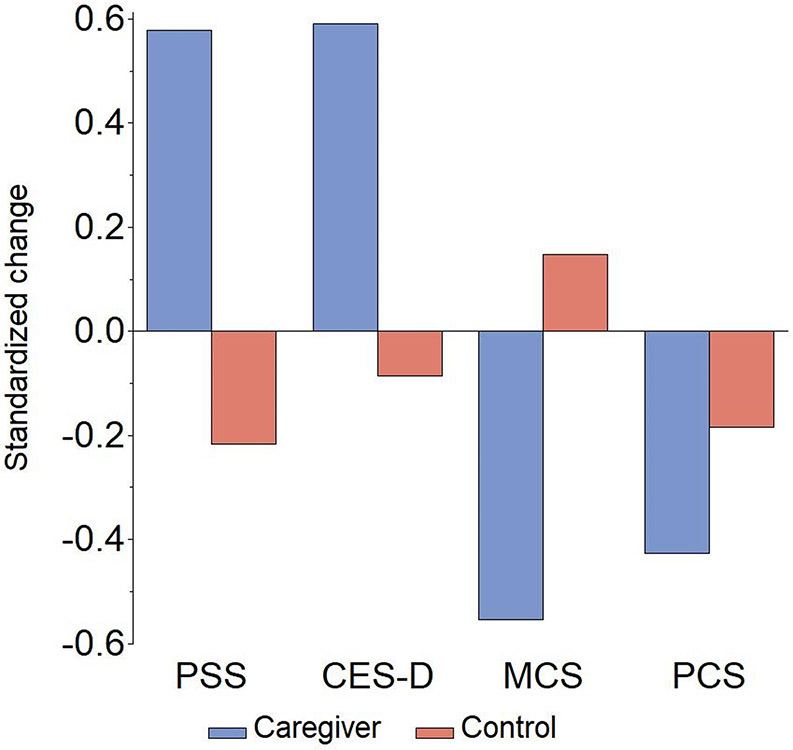

Caregivers showed significantly greater worsening in PSS, CES-D, and MCS, with standardized effect sizes (d) ranging from 0.676 to 0.796 compared with changes in noncaregivers. A significant but smaller effect size was found for worsening PCS in caregivers (0.242). Taking on sustained caregiving was associated with almost a tripling of increased risk of transitioning to clinically significant depressive symptoms at follow up. Effects were not moderated by race, gender, or relationship to care recipient, but younger caregivers showed greater increases in CES-D than older caregivers.

Conclusion:

Persons who began substantial, sustained family caregiving had marked worsening of psychological well-being, and relatively smaller worsening of self-reported physical health, compared with carefully matched noncaregivers. Previous estimates of effect sizes on caregiver well-being have had serious limitations due to use of convenience sampling and cross-sectional comparisons. Researchers, public policy makers, and clinicians should note these strong effects, and caregiver assessment and service provision for psychological well-being deserve increased priority.

Keywords: Stress, caregiving, depression, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Considerable research has addressed burdens of family caregiving1, value of caregiving, and to evaluate interventions for family caregivers.2 There will be demand for even more help from family caregivers in years ahead.3,4

Caregiving is also an important public health issue because of concerns about caregivers’ exposure to high levels of stress, often over sustained periods of time5,6 and the large numbers of Americans providing caregiving. Caregivers have higher rates of depression and anxiety, and lower scores on indicators of quality of life than noncaregivers.7-9 However, it has been challenging to accurately measure the magnitude of these differences because most studies have used cross-sectional comparisons of convenience samples of caregivers and noncaregivers. Caregivers are often drawn from clinics and support groups, likely including caregivers with unusually high levels of distress, and noncaregivers are often volunteers who may be unusually healthy.10 Caregivers drawn from convenience samples are more distressed than caregivers from more representative samples.11 Selection biases, such as assortative mating and shared lifestyle in married couples, may lead to poor health or depression being attributed to caregiving, rather than to shared environment or vulnerabilities in a couple.12 One meta-analysis7 reported substantially lower effect sizes for comparisons of caregivers and noncaregivers in representative samples. Effect sizes for depression were.58 standard deviation units overall, but only .26 when only “representative” samples were examined.

Some studies have used a more rigorous approach, identifying individuals who transitioned to family caregiving over time in population-based studies. This is a superior design since researchers can compare changes over time in individuals who become caregivers, versus noncaregiving controls who may show changes related to age and time but are not affected by caregiving. Despite many studies previously showing that caregivers have poorer psychological well-being than noncaregivers, a 2020 review12 noted that “A more compelling case for the causal relationship between caregiving and psychological distress can be made from longitudinal studies in which individuals are followed into, throughout, and out of the caregiving role.” (p. 640). The existing studies that have used this method have important limitations, including baseline differences on health risk and demographics between caregivers and noncaregivers13 or a low threshold for transition to caregiving, e.g. any assistance with personal care over the previous month or year.14-16

Previous cross sectional research has identified subgroups of caregivers who may be at particularly high risk for negative outcomes from caregiving including female caregivers17,18 and spouse caregivers.19,20 Conversely, Black caregivers often report lower levels of depressive symptoms than White caregivers.21-25 Addressing the impact of gender, race, and relationship to the care recipient on caregiver well-being is challenging to evaluate. For example, women have higher rates of depression than men across the life cycle, regardless of caregiving status,26 and spouse versus adult child caregivers also differ in demographic factors such as age. Prospective methods, evaluating whether those with potential risk factors actually show heightened distress after a transition to caregiving can provide better evidence to identify risk and resilience factors for caregiver distress.

This report examines changes in perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life among individuals in a population-based study who transitioned into a family caregiving role compared to a matched sample of individuals who did not become caregivers over the same time period. We predicted that caregivers would report greater worsening in perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and mental and physical health quality of life over time compared to noncaregiving controls, and explored whether these changes were moderated by sex, race, age, and relationship to the care recipient. We also assessed the magnitude of these within-person changes in response to the onset of caregiving.

METHODS

Participants

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and each participating institution. The research procedures also conform to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The Caregiving Transitions Study (CTS) is an ancillary study of the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.27 A detailed description of the methods of CTS and analyses of changes in inflammation due to caregiving have been reported elsewhere.28,29 REGARDS is an ongoing, prospective cohort study of 30,239 non-Hispanic Black and White community-dwelling participants aged 45+ living in the 48 contiguous US states. Medical history and risk factor information were obtained using a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) and an in-home physical exam including venipuncture. At the baseline, participants were asked “Are you currently providing care on an on-going basis to a family member with a chronic illness or disability? This would include any kind of help such as watching your family member, dressing or bathing this person, arranging care, or providing transportation." Participants who answered “yes” were categorized as caregivers, and those who answered “no” as noncaregivers. Active participants in REGARDS were reassessed 10-13 years later with a Caregiving Screening CATI and in-home assessment including a very similar caregiving question. Participants who were noncaregivers at baseline (N=11,483) were eligible for the CTS. Of these, 1,229 answered “Yes” to being a caregiver at reassessment. Described below are eligibility criteria to identify individuals who became caregivers over time who met our criteria for sufficient exposure to caregiving for adults to qualify for the study, and noncaregivers.

All 1,229 potential incident caregiver were called for Enrollment Interviews and asked when they began serving in the caregiving role (month and year), whether they had been caregiver for this person continuously since that time, their relationship with the care recipient, whether their care recipient currently or previously lived in a nursing home (NH) or assisted living facility (ALF), and how many hours per week they spent providing assistance to the recipient because of his or her health problems or disabilities. The transition into a family caregiving role had to be at least six months after the 1st REGARDS in-home assessment and at least 3 months before the 2nd REGARDS in home assessment. In addition, potential caregivers were excluded if: 1) their care recipient was less than 18 years of age; 2) the care recipient resided in a NH, ALF, or other residential care setting; 3) caregiver provided less than 5 hours of care per week; 4) the caregiver lived more than 50 miles from the care recipient; 5) the participant reported a paid (formal) caregiving relationship, or 6) the caregiver did not provide usable blood samples at either of the REGARDS in-home assessments. Of the 1,229 potential incident caregivers, 931 were ineligible due to one or more exclusions, and 47 otherwise eligible caregivers declined participation, resulting in enrollment of 251 incident caregivers28.

The 10,254 participants who were not caregivers at either assessment were considered as potential noncaregiving control participants. After enrolling incident caregivers, we generated lists of up to five potentially eligible participants who 1) matched the enrolled caregiver on up to 7 demographic and health history factors (age ± 5 years, sex, self-reported race, education level, marital status, self-rated health at baseline and self-reported history of serious cardiovascular disease); and 2) provided usable blood samples for analysis at both in-home assessments. In addition, potential noncaregiving controls who were matched to spouse caregivers had to be married, and those who were matched to adult child caregivers had to have at least one living parent. We attempted to recruit the most closely matched noncaregivers who were willing to participate. Potential controls who were eligible and gave verbal consent to participate completed our Enrollment Interview and caregivers and noncaregivers were administered a series of questionnaires described below by phone.

Measures

All participants completed measures of well-being at the REGARDS baseline. These included the four-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale,30 and a 4-item version of Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),31 for which higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms or perceived stress. They also completed the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12)32 to assess mental health (MCS) and physical health (PCS) components of quality of life, with higher scores representing better quality of life. During the Enrollment Interview, all participants completed these same measures, except for a ten-item form of the CES-D.33 In our analyses, we estimated a 10-item CES-D score from the 4-item CES-D used at REGARDS baseline, using regression analyses similar to those reported in a prior paper on short forms of the CES-D30 for comparison with the follow-up 10-item CES-D measure. We used a cutoff score of 10 or more on the 10-item CES-D to classify participants as having clinically significant depressive symptoms, the more conservative of two cut points proposed.33 Caregivers also reported how many of six activities of daily living (ADL) and eight instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) impairments care recipients had, and if the caregiver assisted with those impairments.34,35

Analyses

Initial analyses were conducted to compare demographic characteristics of caregivers and noncaregivers, and to examine how gender, race, and relationship subgroups differed on demographic characteristics. For these and other analyses, the matched controls of spouse caregivers, adult child caregivers, and other caregivers were placed in these categories since they had been individually matched with these caregivers. Baseline scores for each of these three factors (gender, race, and relationship category) were analyzed by either ANOVA or logistic regression analyses, including 2 X 2 (Gender by Caregiving/Noncaregiving, Race by Caregiving/Noncaregiving) or 3 X 2 (Relationship type by Caregiving/Noncaregiving) comparisons.

For effects on CES-D, PSS, MCS, and PCS, we conducted separate hierarchical regression analyses evaluating predictors of change over time, including differences in change between caregivers and noncaregivers. Covariates were added in steps including 1. The baseline score of the well-being measure, 2. effects for age, gender, and race added, and 3. effects for relationship type (parent versus spouse, and other versus spouse) added. Standardized effect sizes (d) were calculated as the ratio of adjusted mean differences in change between caregivers and noncaregivers divided by square root of the mean square error from the analytic model. We conducted additional analyses to assess for moderator effects for gender, race, age, and relationship category. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline descriptive information on the groups is shown in Table 1 and 2, stratified by gender, race, and relationship category. Caregivers and noncaregivers did not differ significantly at the baseline assessment on gender, race, education, marital status, age, history of major cardiovascular disease, PSS, 4-item CES-D, PCS, MCS, or duration between baseline and follow up assessment.28 There were also no interaction effects of caregiver/noncaregiver status with race, gender, or relationship on any of the demographic characteristics. Thus, the caregivers and noncaregivers were quite similar in their demographic and baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Caregiver and Noncaregiver Demographic and Descriptive Data by Gender and Race

| Variable | Gender | Race | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | White | Black | |||||

| CG | Non- CG |

CG | Non- CG |

CG | Non- CG |

CG | Non- CG |

|

| N | 88 | 88 | 163 | 163 | 161 | 161 | 90 | 90 |

| Sex, Female N (%) | 99 (61.49) |

99 (61.49) |

64 (71.11) |

64 (71.11) |

||||

| Race, African American N (%) | 26 (29.55) |

26 (29.55) |

64 (39.26) |

64 (39.26) |

||||

| Age at Caregiving Transitions Enrollment Interview, M (SD) | 75.33 (8.16) |

75.20 (7.46) |

69.94 (7.38) |

70.23 (7.37) |

72.63 (7.78) |

72.76 (7.48) |

70.40 (8.42) |

70.56 (8.10) |

| Education, College graduate N (%) | 43 (48.86) |

41 (46.59) |

63 (38.65) |

73 (44.79) |

72 (44.72) |

79 (49.07) |

34 (37.78) |

35 (38.89) |

| Self-Rated Health at baseline, N (%) | ||||||||

| Excellent | 28 (31.82) |

16 (18.18) |

33 (20.25) |

38 (23.31) |

47 (29.19) |

40 (24.84) |

14 (15.56) |

14 (15.56) |

| Very Good | 27 (30.68) |

32 (36.36) |

54 (33.13) |

56 (34.36) |

58 (36.02) |

66 (40.99) |

23 (25.56) |

22 (24.44) |

| Good | 27 (30.68) |

33 (37.50) |

57 (34.97) |

55 (33.74) |

42 (26.09) |

43 (26.71) |

42 (46.67) |

45 (50.00) |

| Fair | 5 (5.68) |

7 (7.95) |

17 (10.43) |

14 (8.59) |

11 (6.83) |

12 (7.45) |

11 (12.22) |

9 (10.00) |

| Poor | 1 (1.14) |

0 | 2 (1.23) |

0 | 3 (1.86) |

0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Caregiver and Noncaregiver Demographic and Descriptive Data by Relationship type

| Variable | Spouse | Adult Child | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | Non-CG | CG | Non-CG | CG | Non-CG | |

| N | 128 | 128 | 63 | 63 | 60 | 60 |

| Sex, Female N (%) | 75 (58.59) | 75 (58.59) | 48 (76.19) | 48 (76.19) | 40 (66.67) | 40 (66.67) |

| Race, African American N (%) | 34 (26.56) | 34 (26.56) | 26 (41.27) | 26 (41.27) | 30 (50.00) | 30 (50.00) |

| Age at Caregiving Transitions Enrollment Interview, M (SD) | 74.84 (7.46) | 74.98 (6.62) | 65.87 (6.51) | 64.92 (6.05) | 71.68 (7.34) | 72.95 (6.98) |

| Education, College graduate N (%) | 49 (38.28) | 54 (42.19) | 31 (49.21) | 33 (52.38) | 26 (43.33) | 27 (45.00) |

| Self-Rated Health at REGARDS Baseline N (%) | ||||||

| Excellent | 32 (25.00) | 31 (24.22) | 11 (17.46) | 12 (19.05) | 18 (30.00) | 11 (18.33) |

| Very Good | 39 (30.47) | 38 (29.69) | 29 (46.03) | 28 (44.44) | 13 (21.67) | 22 (36.67) |

| Good | 41 (32.03) | 44 (34.38) | 19 (30.16) | 21 (33.33) | 24 (40.00) | 23 (38.33) |

| Fair | 15 (11.72) | 15 (11.72) | 2 (3.17) | 2 (3.17) | 5 (8.33) | 4 (6.67) |

| Poor | 1 (0.78) | 0 | 2 (3.17) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: REGARDS= REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study

There were some demographic and descriptive differences by gender, race, or relationship type. Female participants were significantly more likely to be Black and to be younger at the baseline than men (39.26% Black among female participants and 29.55% among male, p=0.030; age = 70.09 (7.37) for female and 75.27 (7.80) for male, p<0.001). White participants were significantly older (72.70 (7.62) vs. 70.48 (8.24), p=0.003), and more likely to report excellent or very good health at the baseline than Black participants (65.53% vs. 40.56%, p<0.001). There was a higher percentage of males in the Spouse category than the two other groups (41.41% male in Spouse category, 23.81% in Adult Child and in 33.33% in Other category, overall p=0.003), and the Spouse category had a higher percentage of White participants than the Other category (73.44% White in Spouse category, 58.73% in Adult Child and in 50.00% in Other category, overall p<0.001). Those in the Adult Child category were also significantly younger than participants in the other two categories (65.40 (6.27) for Adult Child, 74.91 (7.04) for Spouse and 72.32 (7.16) for Other, p<0.001). Duration from the REGARDS baseline interview to the Transitions Enrollment interview for caregivers and noncaregivers, and duration of caregiving, were not significantly associated with changes in any of the four dependent variables.

Table 3 presents descriptive data relevant to the magnitude of exposure to caregiving stress. Average scores were well beyond the minimal inclusion criteria. Caregivers averaged over 5 years of caregiving (ranging from 1.6 to 12 years), over 43 hours of care per week, and about 76% resided with the care recipient. They also reported that their care recipients averaged about 2 ADL and 5 IADL impairments, and that they require substantial assistance with ADL and IADL care. About 40% of caregivers reported having a care recipient with dementia.28

Table 3.

Descriptive Data for Caregivers

| Variable | Caregivers |

|---|---|

| N | 251 |

| Caregiving Relationship, N (%) | |

| Spouse | 128 (51.00) |

| Child (or Child-in-Law) of Care Recipient | 63 (25.10) |

| Other | 60 (23.90) |

| Caregiver resides with Care Recipient, N (%) | 190 (75.70) |

| Duration of Caregiving (to Caregiving Transitions Enrollment Interview), Years, M (SD) | 5.78 (2.54) |

| Hours per week of care, M (SD) | 43.30 (29.21) |

| Care Recipient Age at Caregiving Transitions Enrollment Interview, M (SD) | 78.80 (11.29) |

| ADL Impairments | 2.38 (2.30) |

| IADL Impairments | 5.19 (1.48) |

| ADL Care Provided | 2.03 (2.16) |

| IADL Care Provided | 4.73 (1.58) |

Note: ADL=Activities of Daily Living; IADL=Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Results of the regression analyses examining predictors of change in well-being are shown in Table 4. Significantly greater increases in PSS were found for caregivers compared to noncaregivers. This difference remained significant after adjustment for age, gender, race, and relationship type, and there were no significant moderator effects for gender, race, age, or relationship type. There was a significant covariate effect for race. Regardless of caregiving status, White participants showed greater increases over time in perceived stress than Black participants. The covariate adjusted effect size for increase in PSS over time for caregivers compared to noncaregivers (d) was 0.796.

Table 4.

Estimates from hierarchical regression analyses of predictors of change in Perceived Stress, Depressive Symptoms, and Quality of Life

| Outcome | Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS | ||||

| Baseline PSS | −0.611*** | −0.604*** | −0.603*** | |

| Caregiving Status (Caregivers vs. Controls) | 2.046*** | 2.046*** | 2.047*** | |

| Age (years) | --- | 0.019 | 0.028 | |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | --- | 0.307 | 0.315 | |

| Race (Black vs. White) | --- | −0.530* | −0.501* | |

| Relationship (Adult Child vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | 0.326 | |

| Relationship (Other vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | −0.199 | |

| CES-D | ||||

| Baseline CES-D | −0.590*** | −0.599*** | −0.590*** | |

| Caregiving Status (Caregivers vs. Controls) | 3.546*** | 3.527*** | 3.518*** | |

| Age (years) | --- | −0.071* | −0.075* | |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | --- | −0.205 | −0.189 | |

| Race (Black vs. White) | --- | −1.150* | −0.963 | |

| Relationship (Adult Child vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | −0.330 | |

| Relationship (Other vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | −1.290* | |

| SF-12 MCS | ||||

| Baseline SF-12 MCS | −0.559*** | −0.585*** | −0.575*** | |

| Caregiving Status (Caregivers vs. Controls) | −6.041*** | −6.039*** | −6.022*** | |

| Age (years) | --- | 0.093 | 0.121* | |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | --- | −0.790 | −0.826 | |

| Race (Black vs. White) | --- | 1.053 | 0.738 | |

| Relationship (Adult Child vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | 1.394 | |

| Relationship (Other vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | 2.110* | |

| SF-12 PCS | ||||

| Baseline SF-12 PCS | −0.586*** | −0.592*** | −0.592*** | |

| Caregiving Status (Caregivers vs. Controls) | −2.211* | −2.252** | −2.252** | |

| Age (years) | --- | −0.233*** | −0.235*** | |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | --- | −0.245 | −0.248 | |

| Race (Black vs. White) | --- | 1.041 | 1.037 | |

| Relationship (Adult Child vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | −0.106 | |

| Relationship (Other vs. Spouse) | --- | --- | 0.036 |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

p < .0001

PSS=Perceived Stress Scale; CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression 10; SF-12-MCS-SF-12 Mental; SF-12 PCS=SF-12 Physical

Caregivers showed significantly greater increases over time in CES-D than noncaregivers. This difference remained significant after covariate adjustment with an effect size (d) of 0.676 in the final covariate-adjusted model. There was a significant covariate effect for age that was further qualified by a significant interaction effect (see below). A significant covariate effect for relationship type (Other versus Spouse) showed that participants who were categorized as Spouses (either caregiver to a spouse, or a married matched control to a spouse caregiver) showed greater increases in CES-D over time than those who were either caregivers for a relationship other than spouse or parent, or a matched control to such a caregiver.

Moderator effects for the CES-D were not significant for gender, race, or relationship type, but there was a significant age by caregiving status interaction (p=0.02). Examination of this effect showed that the difference in increase in depressive symptoms over time between caregivers and controls was larger in younger individuals compared with older. To illustrate, for age one standard deviation above the mean in the sample (age 80), the difference in increase in CES-D scores for caregivers compared with noncaregivers was 2.51, while for ages one standard deviation below the mean of the sample (age 64) the difference in increase in scores for caregivers compared to controls was 4.58.

We also examined the percentage of participants with clinically significant elevations on the CES-D among caregivers and noncaregivers at baseline and follow up. At baseline, only 4.10% of future caregivers and 5.58% of controls had elevated CES-D scores, which was not a significant difference (p=0.444). At follow up 26.40% of caregivers had clinically significant elevations in CES-D, compared to 10.36% of controls, significantly higher (p<0.001). Among those who were below the cut point at baseline, transition to caregiving was associated with a 2.91 relative risk of scoring over the cut point for clinically significant depressive symptoms on the CES-D at follow-up for caregivers compared to the noncaregiving controls.

For MCS and PCS, caregivers showed significantly greater decreases over time compared with noncaregivers. Subsequent steps show that these differences remain significant after covariate adjustment, with an effect size (d) of −0.700 for MCS and −0.242 for PCS from the covariate-adjusted models. Age and relationship category were significant covariates for MCS, with greater age associated with less declines, and spousal versus other relationship category showing greater declines. Age was the only significant covariate for PCS, with greater age associated with greater declines. No moderator effects were significant.

Figure 1 shows covariate adjusted changes in PSS, CES-D, MCS, and PCS in caregivers and noncaregivers. This figure shows standardized change scores to allow for an illustration of the magnitude of effects and direction of change over time across the two groups and for all four measures. Supplemental figures illustrate the joint main effects of race and caregiving status on changes in perceived stress (Supplemental Figure 1), the interaction of age and caregiving status on changes in CES-D10 (Supplemental Figure 2), and joint main effects of age and caregiving status on change in PCS (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Changes in Perceived Stress (PSS), Depressive Symptoms (CES-D), Mental Health Quality of Life (MCS), and Physical Health Quality of Life (PCS) in Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls (Average duration = 11.7 years)

DISCUSSION

It has been widely reported that caregivers report greater psychological distress and reduced quality of life compared with noncaregivers. Because of the unique methods used in the CTS, the results provide important clarifying information on the impact and magnitude of the effect of caregiving on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and mental and physical health quality of life. For all four variables, caregivers showed more worsening over time than carefully matched noncaregiving controls. Our most important finding is that the negative impact of caregiving on measures of psychological well-being—perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and mental health quality of life, are quite high and higher than found in previous cross-sectional estimates from population-based studies, with effect sizes ranging from 0.676 to 0.796. These effect sizes are between the classic “medium” (0.50) and “large” (0.80) effect sizes as defined by Cohen36 and generally larger than effect sizes extracted from cross-sectional comparisons of caregivers and noncaregivers.7 In addition, we found that substantial and sustained caregiving nearly triples the risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms. The effect size for change in physical health quality of life was substantially smaller (−0.242), consistent with previous meta-analyses showing smaller effects for physical versus mental health7.

While female gender, White race, and spouse caregiving have commonly been found to be associated with higher distress in caregivers, we found that these factors did not elevate risk for heighted distress after the transition to caregiving for the outcomes of perceived stress, or mental or physical health quality of life. Previous analyses of these differences by gender, race, and relationship category have largely used cross-sectional comparisons and convenience samples, have not carefully matched caregivers and noncaregivers, and adjusted for covariates to the extent that this project has. These findings challenge the idea that these factors increase vulnerability to caregiving stress.

We found only one statistically significant moderator effect out of 16 such analyses, that younger participants who became caregivers showed greater increases in depressive symptoms than older caregivers in comparison with their respective noncaregiving control participants. The finding that younger caregivers show greater risk for increased depressive symptoms when becoming caregivers is interesting, and consistent with research that shows that advanced age may be associated with advantages in coping with some stressful events, due to the “positivity effect” and improved emotional regulation in older adults, accumulations of experience, expectations that such events are “on time” in the life cycle, and fewer conflicting roles such as employment that may add to the challenges of caregiving37-40. Age differences could also be due to factors such as differences in caregiving assistance, which we did not assess.

Our research design including caregivers and noncaregivers that were comparable at baseline on multiple demographic factors, and longitudinal follow-up provides a better gauge of changes over time attributable to caregiving than a design including caregivers alone. For example, we found that age was a significant covariate predicting change in physical health quality of life, and both caregivers and controls reported declines in physical health quality of life over time. Without the noncaregiving control group, a finding of decline in caregiver health over time would have overestimated the magnitude of effect by not considering declines occurring in aging noncaregivers.

Limitations include the exclusion of other minority groups, and selective attrition in the parent REGARDS study, which has reported that attrition was increased in older (over age 80), male, and Black participants.41 Our method emphasized studying sustained caregiving, so caregivers whose care recipients were deceased or placed in nursing homes were also excluded. These exclusions are important to acknowledge and have implications for the generalizability of our sample. Since our CTS enrollment assessments were taken years after the REGARDS baseline, there could have been multiple unmeasured events during this interval as well. All of these limitations limit our ability to prove a causal relationship between caregiving and diminished well-being. Given our emphasis on examining differences between caregivers and noncaregivers, and our focus on moderators such as age which are not modifiable, this manuscript does not include new information on ways that mutable factors, such as individual differences in caregiving stressors or resources (e.g. hours of care, stress appraisals, and benefit finding), might affect the well-being of caregivers. Future papers from our project will address such potentially modifiable factors.

From a clinical perspective, our results confirm widely reported findings that caregivers face considerable strain and that this can have negative effects on well-being. There is a large body of evidence documenting effectiveness of evidence-based interventions to improve well-being in caregivers,2 and a number of important policy changes have been implemented and proposed to support caregivers.42 There is substantial evidence that unavailability of a caregiver, and high levels of caregiver distress, are important predictors of nursing home placement43,44, and poor care recipient health outcomes45 and higher costs46. More widespread inclusion of caregiver assessment as part of comprehensive geriatric assessment across diverse settings has been recommended by several authors47-49 and our results confirm the substantial and clinically significant effects of caregiving on well-being.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Changes in Perceived Stress (PSS) Among Black and White Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls.

Supplemental Figure 2. Changes in Depressive Symptoms (CES-D) among Older and Younger Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls (yo=Years Old)

Supplemental Figure 3. Changes in Physical Health Quality of Life (PCS) among Older and Younger Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls (yo=Years Old)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sponsor’s Role:

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement [U01 NS041588] co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; and by an investigator-initiated grant [RF1 AG050609] from the NIA.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or NIA. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at https://www.uab.edu/soph/regardsstudy/

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL, Fried T. Multifactorial examination of caregiver burden in a national sample of family and unpaid caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(2):277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz R, Eden J. Families Caring for An Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redfoot D, Feinberg L, Houser A. The Aging of the Baby Boom and the Growing Care Gap: A Look at Future Declines in the Availability of Family Caregivers. Insight Issues, AARP Public Policy Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vespa J, Armstrong DM, Medina L. Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health 2007;97(2):224–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson LA, Edwards VJ, Pearson WS, Talley RC, McGuire LC, Andresen EM. Adult caregivers in the United States: characteristics and differences in well-being, by caregiver age and caregiving status. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 2003;18(2):250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, Berry JW, Hughes GH. Psychological, social, and health consequences of caring for a relative with senile dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987;25:405–411. F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Hinckley M, Salloway S, Miller IW. Evidence for the validity of the American medical association's caregiver self-assessment questionnaire as a screening measure for depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58(2):387–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist 2015;55(2):309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pruchno RA, Brill JE, Shands Y, et al. Convenience samples and caregiving research: how generalizable are the findings? Gerontologist 2008;48(6):820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz R, Beach SR, Czaja SJ, Martire LM, Monin JK. Family caregiving for older adults. Annu Rev Psychol 2020;71:635–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton LC, Zdaniuk B, Schulz R, Jackson S, Hirsch C. Transitions in spousal caregiving. Gerontologist 2003;43:230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirst M Carer distress: a prospective, population-based study. Soc Sci Med 2005;61(3):697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marks NF, Lambert JD, Choi H. Transitions to caregiving, gender, and psychological well-being: a prospective US national study. J of Marriage Fam 2002:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rafnsson SB, Shankar A, Steptoe A. Informal caregiving transitions, subjective well-being and depressed mood: findings from the english longitudinal study of ageing. Aging Ment Health 2017;21(1):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2006;61(1):P33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penning MJ, Wu Z. Caregiver stress and mental health: impact of caregiving relationship and gender. Gerontologist 2016;56(6):1102–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: a meta-analytic comparison. Psychol Aging 2011;26(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chappell NL, Dujela C, Smith A. Spouse and adult child differences in caregiving burden. Can J Aging 2014;33(4):462–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: a 20-year review (1980-2000). Gerontologist 2002;42(2):237–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haley WE, West CA, Wadley VG, et al. Psychological, social, and health impact of caregiving: a comparison of black and white dementia family caregivers and noncaregivers. Psychol Aging 1995;10(4):540–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist 2005;45(1):90–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capistrant BD. Caregiving for older adults and the caregivers' health: an epidemiologic review. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2016;3:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu C, Badana ANS, Burgdorf J, Fabius CD, Roth DL, Haley WE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of racial and ethnic differences in dementia caregivers' well-being. Gerontologist. 2020. 10.1093/geront/gnaa028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girgus JS, Yang K, Ferri CV. The gender difference in depression: are elderly women at greater risk for depression than elderly men? Geriatrics (Basel) 2017;2(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth DL, Haley WE, Rhodes JD, et al. Transitions to family caregiving: enrolling incident caregivers and matched non-caregiving controls from a population-based study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019. 10.1007/s40520-019-01370-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth DL, Haley WE, Sheehan OC, et al. The transition to family caregiving and its effect on biomarkers of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020. https://doi/10.1073/pnas.2000792117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melchior LA, Huba G, Brown VB, Reback CJ. A short depression index for women. Educ Psychol Meas 1993;53(4):1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JE, Kisinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the ces-d. Am J Prev Med 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. the index of adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carstensen LL, DeLiema M. The positivity effect: A negativity bias in youth fades with age. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018;19:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurera JW, Isaacowitz DM. Emotion regulation and emotion perception in aging: A perspective on age-related differences and similarities. Prog Brain Res 2019;247:329–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aldwin C Stress and coping across the lifespan. In: Folkman S, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohl NM, Mossakowski KN, Sanidad II. Bird OT, & Nitz LH. Does the Health of Adult Child Caregivers Vary by Employment Status in the United States? J Aging Health 2019;31(9),:1631–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long DL, Howard G, Long DM, et al. An Investigation of selection Bias in estimating racial disparity in stroke risk factors: The REGARDS study. Am J Epidemio. 2019;188(3):587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reinhard SC, Feinberg LF, Choula R, Houser A. Valuing the invaluable: 2015 update. Insight on the Issues. 2015;104:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blackburn J, Albright KC, Haley WE, et al. Men lacking a caregiver have greater risk of long-term nursing home placement after stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:133–139. 10.1111/jgs.15166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolff JL, Mulcahy J, Roth DL,et al. Long-term nursing home entry: a prognostic model for older adults with a family or unpaid caregiver. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(10):1887–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stall NM, Kim SJ, Hardacre KA, et al. Association of informal caregiver distress with health outcomes of community-dwelling dementia care recipients: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(3):609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ankuda CK, Maust DT, Kabeto MU, McCammon RJ, Langa KM, Levine DA. Association between spousal caregiver well-being and care recipient healthcare expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(10):2220–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis ML, Hendrickson J, Wilson N, Shrestha S, Amspoker AB, Kunik M. Taking Care of the Dyad: Frequency of Caregiver Assessment Among Veterans with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(8):1604–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riffin C, Wolff JL, Estill M, Prabhu S, Pillemer KA. Caregiver Needs Assessment in Primary Care: Views of Clinicians, Staff, Patients, and Caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020. 10.1111/jgs.16401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill T Caregiver Assessment Is Critical to Home-Based Medical Care Quality. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20(5):650–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Changes in Perceived Stress (PSS) Among Black and White Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls.

Supplemental Figure 2. Changes in Depressive Symptoms (CES-D) among Older and Younger Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls (yo=Years Old)

Supplemental Figure 3. Changes in Physical Health Quality of Life (PCS) among Older and Younger Caregivers and Noncaregiving Controls (yo=Years Old)