Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is a highly contagious and highly pathogenic disease caused by a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, and it has become a pandemic. As a vulnerable population, university students are at high risk during the epidemic, as they have high mobility and often overlook the severity of the disease because they receive incomplete information about the epidemic. In addition to the risk of death from infection, the epidemic has placed substantial psychological pressure on the public. In this respect, university students are more prone to psychological problems induced by the epidemic compared to the general population because for most students, university life is their first time outside the structure of the family, and their mental development is still immature. Internal and external expectations and academic stress lead to excessive pressure on students, and unhealthy lifestyles also deteriorate their mental health. The outbreak of COVID-19 was a significant social event, and it could potentially have a great impact on the life and the mental health of university students. Therefore, it is of importance to investigate university students’ mental health status during the outbreak of COVID-19.

Objective

The principal objective of this study was to investigate the influencing factors of the psychological responses of Chinese university students during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

This study used data from a survey conducted in China between February 21 and 24, 2020, and the data set contains demographic information and psychological measures including the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, the Self-Rating Depression Scale, and the compulsive behaviors portion of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. A total of 2284 questionnaires were returned, and 2270 of them were valid and were used for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples and binary logistic regression models were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Our study surveyed 563 medical students and 1707 nonmedical students. Among them, 251/2270 students (11.06%) had mental health issues. The results showed that contact history of similar infectious disease (odds ratio [OR] 3.363, P=.02), past medical history (OR 3.282, P<.001), and compulsive behaviors (OR 3.525, P<.001) contributed to the risk of mental health issues. Older students (OR 0.928, P=.02), regular daily life during the epidemic outbreak (OR 0.410, P<.001), exercise during the epidemic outbreak (OR 0.456, P<.001), and concern related to COVID-19 (OR 0.638, P=.002) were protective factors for mental health issues.

Conclusions

According to the study results, mental health issues have seriously affected university students, and our results are beneficial for identifying groups of university students who are at risk for possible mental health issues so that universities and families can prevent or intervene in the development of potential mental health issues at the early stage of their development.

Keywords: university students, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, mental health status, COVID-19, pandemic, mental health, anxiety, psychological health

Introduction

A novel coronavirus pneumonia disease, COVID-19, spread very quickly across China in early 2020 [1]. The outbreak was first discovered in late December 2019, when a series of unexplained pneumonia cases were identified that were related to epidemiologically undiscovered seafood market exposure in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [2]. According to the official website of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, on July 31, 2020, a total of 84,337 confirmed cases had accumulated, including 78,989 discharged cases and 4634 deaths; a total of 789,742 close contacts were tracked, and 20,278 close contacts were still under medical observation [3]. The World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020 [4]. More than 83 million confirmed infection cases across more than 200 countries globally had been reported as of December 31, 2020, including over 1.82 million deaths [5]. The advanced and rapid spread of COVID-19 has brought many complex challenges to the global public health and medical communities.

COVID-19 has brought the risk of death from infection and unbearable psychological pressure to people worldwide [6]. Previous research has shown that the COVID-19 has had a broad psychosocial impact on humans at the individual level, where people may feel fear of illness or death, helplessness, and stigma [7]. During a public health emergency, approximately 10% to 30% of the public are very concerned or quite concerned about the possibility of contracting the disease [8]. As schools and businesses are closed due to the pandemic, individuals’ negative emotions become more complicated [9]. Many studies investigated the psychological impact on uninfected communities during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak and found a significant mental illness incidence [10]. Studies also found some risk factors for the deterioration of mental health: being female [11,12], having a medical history, such as prior psychiatric illness, physical illness, or chronic disease [13-15], being unmarried [16-18], having lower income [13,16,19], and experiencing a negative economic impact [20]. People who were more likely to take preventive measures against the infection were older, female, and highly educated; they also had intensive awareness of SARS, a moderate level of anxiety, and a positive contact history [21].

An essential part of the population is university students, who are under heavy study pressure and have unhealthy lifestyles; more importantly, the university stage is a stage of transition to maturity in life development. During university studies, the social knowledge that students have acquired may be insufficient to understand the pandemic due to the limited social activities of students compared with that of working adults [22]. Therefore, the students are not inclined to find ways to release pressure, which can lead to unstable mental states, and the situation can worsen in epidemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, the sources of COVID-19 infection may be study places at the university, and populations of hundreds of millions of students are at risk of spreading the virus [23]. Many studies have shown that the outbreak of infectious diseases will have a psychological impact on the general population, including medical staff and university students. A prominent example is the mental sequelae observed during the outbreak of SARS in 2003 [24]. Studies of the SARS outbreak have shown that medical staff experienced acute stress reactions [25,26]. However, medical students also require attention because they are students with fragile mental endurance and medical workers without complete medical training, and their exposure risks are higher than those of other people.

Therefore, the aim of our study is to investigate the mental health of university students and its influencing factors during the COVID-19 pandemic on groups of both medical and nonmedical students. In this study, we conducted a survey of the targeted sample with the aims to explore risk factors that contributed to mental disease during the pandemic and to provide evidence for psychological intervention programs for university students. This research is essential for students’ healthy growth and is an effective response to future work and mental health interventions for students.

Methods

Study Population and Sample

The targeted population included medical students from 57 universities in China. In this study, a cross-sectional survey was developed, and anonymous web-based questionnaires were used to investigate students’ mental health status during the COVID-19 epidemic. A snowball sampling strategy was used; the web-based survey was first distributed to medical students, and they were encouraged to pass it on to others. A total of 2284 questionnaires were returned, and 14 of them were excluded because the respondents did not fill in the answers completely or did not meet the criteria of the survey; for example, some respondents were teachers and not students. A total of 2270 valid questionnaires were finalized in the study, including surveys from 563 medical students and 1707 nonmedical students.

Study Instruments

The questionnaire contained the demographic information and psychological measures, which include the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and the compulsive behaviors part of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS).

Demographic Information

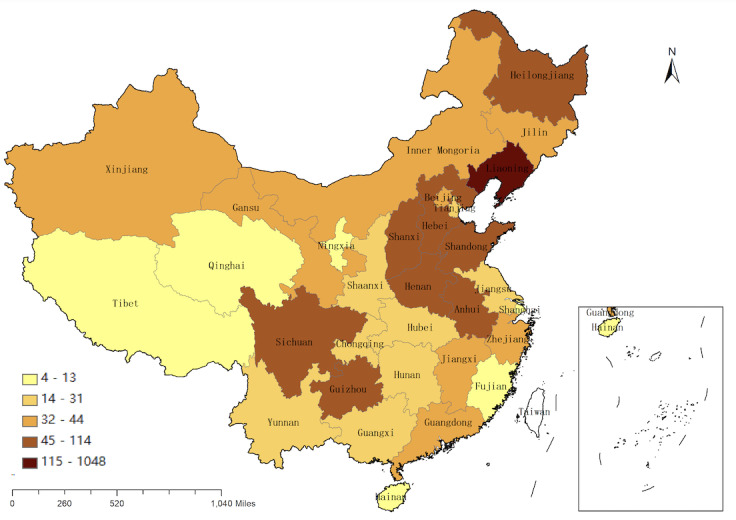

The questions on demographic information in this study were related to gender, age, whether the respondent is an only child, ethnicity, place of residence, region of residence, whether the respondent has participated in volunteer work, contact history of similar infectious disease, past medical history, regularity of daily life and exercise during the epidemic, and concern about COVID-19. The geographical distribution map of the participants was depicted by ArcGIS software (Esri), and the cutoff points for classification were based on the Jenks classification technique as employed in ArcGIS, version 10.5.

The SAS and SDS

The SAS and SDS [27,28] were developed by William WK Zung, a psychiatrist at Duke University. Both the SAS and SDS are Likert scale surveys. They each contain 20 items of self-report examination that measure the level of anxiety symptoms (SAS) or depressive symptoms (SDS). The scores of the 20 items are added in each scale and then converted into standard scores, where higher scores represent more severe anxiety or depression. Based on the Chinese norm, people who score more than 50 on the SAS scale are defined as having anxiety symptoms, and people who score more than 53 on the SDS are treated as having depressive issues. The SAS demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach ɑ=.828), and the SDS also showed good internal consistency (Cronbach ɑ=.849).

The YBOCS

The YBOCS was developed to remedy problems with existing rating scales by providing a specific measure of the severity of symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [29]. This measure ensures that the mental disorder will not be influenced by the type of obsessions or compulsions present. The scale is clinician rated and includes 10 items; a score >6 indicates compulsive behavior. In this study, we used only part of the compulsive behaviors scale of the YBOCS, and it demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach ɑ=.810).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 26.0 (IBM Corporation). According to the data type, the Mann-Whitney U test, a type of nonparametric test, was used to explore the significant associations between sample characteristics and mental health issues during the COVID-19 epidemic. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted for dependent variables (mental health issues) and independent variables (demographic and psychological measures), and we set the level of statistical significance as P<.05.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles and its later amendments, and the study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Experimentation of China Medical University (EC-2020-KS-025). The study procedures followed ethical standards. The participants were informed of the study protocol, and consent was received from all the participants. All participation was voluntary and anonymous. Confidentiality was ensured in processing personal data and maintaining individual records.

Results

The characteristics and other demographic information in the valid sample of 2270 respondents are summarized in Table 1. In this study, a new dependent variable (mental health issues) was created to evaluate which independent variables affected the mental health of university students, and the samples with positive mental health issues included students with both positive anxiety symptoms and positive depression symptoms. The results showed that 251 out of 2270 students (11.1%) had mental health issues; among these 251 students, 106 were male (42.2%) and 145 were female (57.8%). Of these 251 students, 214 (85.3%) were between 19 and 24 years of age. The distribution of participants covered the country of China, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and mental health issues among students (N=2270).

| Variable | Total, n (%)a | Anxiety symptoms, n (%) | Depressive symptoms, n (%) | Mental health issues, n (%) | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Male | 877 (38.6) | 47 (5.4) | 830 (94.6) | 96 (10.9) | 781 (89.1) | 106 (12.1) | 771 (87.9) | |||||||

|

|

Female | 1393 (61.4) | 39 (2.8) | 1354 (97.2) | 141 (10.1) | 1252 (89.9) | 145 (10.4) | 1248 (89.6) | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||

|

|

<18 | 250 (11) | 10 (4) | 240 (96) | 31 (12.4) | 219 (87.6) | 33 (13.2) | 217 (86.8) | |||||||

|

|

19-24 | 1926 (84.8) | 73 (3.8) | 1853 (96.2) | 204 (10.6) | 1722 (89.4) | 214 (11.1) | 1712 (88.9) | |||||||

|

|

≥25 | 94 (4.1) | 3 (3.2) | 91 (96.8) | 2 (2.1) | 92 (97.9) | 4 (4.3) | 90 (95.7) | |||||||

| Only child | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 1051 (46.3) | 43 (4.1) | 1008 (95.9) | 112 (10.7) | 939 (89.3) | 120 (11.4) | 931 (88.6) | |||||||

|

|

No | 1219 (53.7) | 43 (3.5) | 1176 (96.5) | 125 (10.3) | 1094 (89.7) | 131 (10.7) | 1088 (89.3) | |||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Han | 1936 (85.3) | 76 (3.9) | 1860 (96.1) | 206 (10.6) | 1730 (89.4) | 215 (11.1) | 1721 (88.9) | |||||||

|

|

Minority | 334 (14.7) | 10 (3.0) | 324 (97.0) | 31 (9.3) | 303 (90.7) | 36 (10.8) | 298 (89.2) | |||||||

| Place of residence | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Urban | 938 (41.3) | 34 (3.6) | 904 (96.4) | 98 (10.4) | 840 (89.6) | 103 (11.0) | 835 (89.0) | |||||||

|

|

Rural | 1332 (58.7) | 52 (3.9) | 1280 (96.1) | 139 (10.4) | 1193 (89.6) | 148 (11.1) | 1184 (88.9) | |||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Hubei Province | 26 (1.1) | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | 2 (7.7) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | 24 (92.3) | |||||||

|

|

Outside Hubei Province | 2244 (99) | 85 (3.8) | 2159 (96.2) | 235 (10.5) | 2009 (89.5) | 249 (11.1) | 1995 (88.9) | |||||||

| Joined in volunteer work | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 246 (10.8) | 9 (3.7) | 237 (96.3) | 30 (12.2) | 216 (87.8) | 31 (12.6) | 215 (87.4) | |||||||

|

|

No | 2024 (89.2) | 77 (3.8) | 1947 (96.2) | 207 (10.2) | 1817 (89.8) | 220 (10.9) | 1804 (89.1) | |||||||

| Contact history of similar infectious disease | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 23 (1) | 4 (17.4) | 19 (82.6) | 8 (34.8) | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) | 15 (65.2) | |||||||

|

|

No | 2247 (99) | 82 (3.6) | 2165 (96.4) | 229 (10.2) | 2018 (89.8) | 243 (10.8) | 2004 (89.2) | |||||||

| Past medical history | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 101 (4.4) | 12 (11.9) | 89 (88.1) | 27 (26.7) | 74 (73.3) | 29 (28.7) | 72 (71.3) | |||||||

|

|

No | 2169 (95.6) | 74 (3.4) | 2095 (96.6) | 210 (9.7) | 1959 (90.3) | 222 (10.2) | 1947 (89.8) | |||||||

| Compulsive behaviors | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Yes | 313 (13.8) | 35 (11.2) | 278 (88.8) | 76 (24.3) | 237 (75.7) | 81 (25.9) | 232 (74.1) | |||||||

|

|

No | 1957 (89.2) | 51 (2.6) | 1906 (97.4) | 161 (8.2) | 1796 (91.8) | 170 (8.7) | 1787 (91.3) | |||||||

| Regularity of daily life | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Regular | 1301 (57.3) | 19 (1.5) | 1282 (98.5) | 76 (5.8) | 1225 (94.2) | 79(6.1) | 1222 (93.9) | |||||||

|

|

Irregular | 969 (42.7) | 67 (6.9) | 902 (93.1) | 161 (16,6) | 808 (83.4) | 172 (17.8) | 797 (82.2) | |||||||

| Exercise | |||||||||||||||

|

|

No exercise | 809 (35.6) | 47 (5.8) | 762 (94.2) | 135 (16.7) | 674 (83.3) | 143 (17.7) | 666 (82.3) | |||||||

|

|

Continued exercise | 1461 (64.4) | 39 (2.7) | 1422 (97.3) | 102 (7.0) | 1359 (93.0) | 108 (7.4) | 1353 (92.6) | |||||||

| Concern about COVID-19 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Not very concerned (<1 hour per day) |

1036 (45.6) | 32 (3.1) | 1004 (96.9) | 131 (12.6) | 905 (87.4) | 135 (13.0) | 901 (87.0) | |||||||

|

|

Very concerned (>1 hour per day) |

1234 (54.4) | 54 (4.4) | 1180 (95.6) | 106 (8.6) | 1128 (91.4) | 116 (9.4) | 1118 (90.6) | |||||||

| Student type | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Medical student | 563 (24.8) | 20 (3.6) | 543 (96.4) | 57 (10.1) | 506 (89.9) | 60 (10.7) | 503 (89.3) | |||||||

|

|

Nonmedical student | 1707 (75.2) | 66 (3.9) | 1641 (96.1) | 180 (10.5) | 1527 (89.5) | 191 (11.2) | 1516 (88.8) | |||||||

| Total | 2270 (100) | 86 (3.8) | 2184 (96.2) | 237 (10.4) | 2033 (89.6) | 251 (11.1) | 2019 (88.9) | ||||||||

aPercentages in the Total column are calculated based on N=2270; all other percentages are calculated based on the values in the Total column.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution map of the 2270 study participants.

The Mann-Whitney U test shows that age, contact history of similar infectious disease, past medical history, compulsive behaviors, the regularity of daily life during the epidemic outbreak, exercise during the epidemic outbreak, and concern about COVID-19 were correlated with mental health issues (all P<.05), as shown in Table 2. However, gender, being an only child, ethnicity, place of residence, region, joining in volunteer work, and student type (medical vs nonmedical) had no statistically significant associations with mental health issues (all P>.05).

Table 2.

Mann-Whitney U tests and z scores of factors affecting students’ mental health issues as the grouping variable.

| Variable (factor) | Mann-Whitney U | Mann-Whitney z | P value |

| Gender (X8) | 243138.00 | –1.241 | .22 |

| Age (X1) | 241098.00 | –2.015 | .04 |

| Only child (X11) | 249085.00 | –0.508 | .61 |

| Ethnicity (X13) | 252327.50 | –0.176 | .86 |

| Place of residence (X14) | 252570.50 | –0.097 | .92 |

| Region (X10) | 252391.50 | –0.550 | .58 |

| Joining in volunteer work (X9) | 249072.50 | –0.818 | .41 |

| Contact history of similar infectious disease (X2) | 247191.00 | –3.646 | <.001 |

| Past medical history (X3) | 233145.00 | –5.787 | <.001 |

| Compulsive behaviors (X4) | 200731.00 | –9.003 | <.001 |

| Regularity of daily life (X5) | 179774.00 | –8.774 | <.001 |

| Exercise (X6) | 192609.00 | –7.481 | <.001 |

| Concern about COVID-19 (X7) | 230177.50 | –2.747 | .006 |

| Student type (X12) | 250828.00 | –0.349 | .73 |

The above 7 factors (age, contact history of similar infectious disease, past medical history, compulsory behaviors, regularity of daily life, exercise, and concern about COVID-19) that had a significant association (P<.05) in the Mann-Whitney U test were entered into binary logistic regression model 1 as independent variables for mental health issues. Likewise, all the other above factors were entered into the binary logistic regression model in order of P value from small to large (the order is indicated in Table 2). First, we analyzed the overall effectiveness of these models (Table 3). The original hypothesis of the model test was that the quality of the model would be the same if the independent variable was or was not included. The results showed that the P value is <.05, which means that the original hypothesis is rejected, and the construction of these models is meaningful; moreover, based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) goodness-of-fit statistic for comparing models, model 1 (AIC=1397.629), with the lowest AIC statistic, is the model with the best fit.

Table 3.

Model summary of binary logistic regression analysis of students’ mental health issues.

| Model | –2 log likelihood | Chi-square (df) | P value | AICa | BICb |

| Intercept-only | 1578.608 | N/Ac | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Model 1 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7) | 1381.629 | 196.979 (7) | <.001 | 1397.629 | 1443.449 |

| Model 2 (X1 ,X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8) | 1380.594 | 198.014 (8) | <.001 | 1398.594 | 1450.142 |

| Model 3 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9) | 1378.846 | 199.762 (9) | <.001 | 1398.846 | 1456.121 |

| Model 4 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10) | 1378.483 | 200.125 (10) | <.001 | 1400.483 | 1463.486 |

| Model 5 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10, X11) | 1378.313 | 200.295 (11) | <.001 | 1402.313 | 1471.044 |

| Model 6 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10, X11, X12) | 1377.973 | 200.635 (12) | <.001 | 1403.973 | 1478.431 |

| Model 7 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10, X11, X12, X13) | 1377.778 | 200.830 (13) | <.001 | 1405.778 | 1485.963 |

| Model 8 (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, X10, X11, X12, X13, X14) | 1377.540 | 201.068 (14) | <.001 | 1407.540 | 1493.453 |

aAIC: Akaike information criterion.

bBIC: Bayesian information criterion.

cN/A: not applicable.

As shown in Table 4, the above 7 factors in the optimal model (Model 1) were used as independent variables, and mental health issues were used as the dependent variable for binary logistic regression analysis; the formula of the model was  = 0.618 – 0.075 × X1 + 1.213 × X2 + 1.188 × X3 + 1.260 × X4 – 0.892 × X5 – 0.786 × X6 – 0.450 × X7 (where P represents the probability that mental health issues are positive and 1 – P represents the probability that mental health issues are negative). The analysis indicates that age (odds ratio [OR] 0.928, P=.02), regular daily life during the epidemic outbreak (OR=0.410, P<.001), exercise during the epidemic outbreak (OR 0.456, P<.001), and concern about COVID-19 (OR 0.638, P=.002) were protective factors for mental health issues, as shown in Table 3. The results showed that older students and students who maintained regular daily life activity and physical exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic were less likely to have mental health issues. However, contact history of similar infectious disease (OR 3.363, P=.02), past medical history (OR 3.282, P<.001), and compulsive behaviors (OR 3.525, P<.001) were risk factors for mental health issues; this finding showed that students with these three conditions were more likely to have mental health issues.

= 0.618 – 0.075 × X1 + 1.213 × X2 + 1.188 × X3 + 1.260 × X4 – 0.892 × X5 – 0.786 × X6 – 0.450 × X7 (where P represents the probability that mental health issues are positive and 1 – P represents the probability that mental health issues are negative). The analysis indicates that age (odds ratio [OR] 0.928, P=.02), regular daily life during the epidemic outbreak (OR=0.410, P<.001), exercise during the epidemic outbreak (OR 0.456, P<.001), and concern about COVID-19 (OR 0.638, P=.002) were protective factors for mental health issues, as shown in Table 3. The results showed that older students and students who maintained regular daily life activity and physical exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic were less likely to have mental health issues. However, contact history of similar infectious disease (OR 3.363, P=.02), past medical history (OR 3.282, P<.001), and compulsive behaviors (OR 3.525, P<.001) were risk factors for mental health issues; this finding showed that students with these three conditions were more likely to have mental health issues.

Table 4.

Estimations of binary logistic regression analysis of students’ mental health issues as the dependent variable.

| Variable | Mental health issues | ||||

|

|

B | SE | z | P value | Exp(B) (95% CI) |

| Age | –0.075 | 0.033 | –2.301 | .02 | 0.928 (0.870-0.989) |

| Contact history of similar infectious disease (yes vs no) | 1.213 | 0.501 | 2.422 | .02 | 3.363 (1.260-8.976) |

| Past medical history (yes vs no) | 1.188 | 0.251 | 4.736 | <.001 | 3.282 (2.007-5.367) |

| Compulsive behaviors (yes vs no) | 1.260 | 0.167 | 7.554 | <.001 | 3.525 (2.542-4.887) |

| Regularity of daily life (regular vs irregular) | –0.892 | 0.150 | –5.936 | <.001 | 0.410 (0.305-0.550) |

| Exercise (yes vs no) | –0.786 | 0.144 | –5.446 | <.001 | 0.456 (0.344-0.605) |

| Concern about COVID-19 (yes vs no) | –0.450 | 0.147 | –3.066 | .002 | 0.638 (0.478-0.850) |

| Constant | 0.618 | 0.691 | 0.894 | .37 | 1.855 (0.479-7.182) |

Discussion

Principal Findings

In our study, we analyzed the psychological responses and associated factors, including risk factors and protective factors, of both medical and nonmedical students after the outbreak of COVID-19. We found that past medical history, contact history of similar infectious diseases, and compulsive behaviors contributed to the risk of mental health issues. Maintenance of regular daily life and exercise during the epidemic outbreak, older age, and high levels of concern (>1 hour per day) about COVID-19 were protective factors for mental health issues.

The COVID-19 outbreak is the largest outbreak of atypical pneumonia since SARS in 2003 in terms of the number of infection cases and time of spread [30]. COVID-19, compared with SARS, has brought greater risk of death and very high psychological pressure to people worldwide due to its power of “superspreading” among humans [6,31]. Studies have demonstrated the psychological impact of the early stage of COVID-19 on the general population, including college students [32-34], and it has been indicated that both medically trained medical staff and nonmedical health care personnel can be affected [35,36]. Our study provided evidence that 251/2270 students (11.1%) encountered mental health issues during the outbreak of COVID-19. During the continuous spread of the epidemic, strict isolation measures and closures in campuses across China may have affected university students’ mental health [37,38]. More importantly, medical students who are medical workers with incomplete training possess only basic medical knowledge and do not have proficient professional skills and abundant clinical experience. Therefore, their clinical exposure risks are higher than those of other people. Likewise, the mental health of medical students requires attention during the pandemic.

A few studies reporting the psychological conditions of college students or medical students during the COVID-19 outbreak emerged during the preparation of our manuscript. Copeland et al [39] investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the emotions, behaviors, and wellness behaviors of first-year college students and showed that COVID-19 and related mitigation strategies have a moderate but continuous impact on mood and healthy behavior. Bolatov et al [40] compared the mental state of medical students switching to web-based learning with that of students who received traditional learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they revealed that the prevalence of burnout syndrome, depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms decreased after the transition. Li et al [41] investigated the rates of three mental health problems (acute stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms) and their change patterns in two phases of the pandemic (early vs under control), and they showed that the significant predictors of distinct mental health trajectories included senior students, COVID-19 exposure, COVID-19–related worries, social support, and family function. Isralowitz et al [42] examined COVID-19–related fear and its association with psychoemotional conditions, including use of substances such as tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis, among Israeli and Russian social work students at two peak points or waves of infection. These literature reports focused on a specific population or condition, a relatively small sample size, and limited survey items during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with the above studies, our survey covered a large population of both medical and nonmedical university students, from undergraduates to graduates, with a wide geographical range using multidimensional survey items, including detailed demographic information and mental and behavioral status, and we analyzed the factors associated with the psychological responses. Our results are more specific and detailed.

Our study focused on the psychological status of university students and concluded that university students with compulsive behaviors are more likely to have mental health issues, which confirmed the conclusions of previous research. The research has suggested that youth with OCD are at risk of experiencing comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety [43]. Students with past medical history are more likely to have anxiety and depression symptoms; this is consistent with recent research findings, in which a medical history of issues such as prior psychiatric illness, physical illness, or chronic disease was a risk factor for the deterioration of mental health [13-15], and indicates that these students are more sensitive to the epidemic and require more psychological intervention.

University students with irregular daily life during the epidemic outbreak were more likely to have mental health issues, which is similar to previous research results. Previous studies have suggested that with the increasing pressure of modern life and irregular lifestyles, depression has become an increasing threat to human health. Studies have also suggested that better mental health at baseline was predicted by a lower body mass index, a higher frequency of physical and mental activities, nonsmoking, a nonvegetarian diet, and a more regular social rhythm [44]. Students should maintain a regular and healthy lifestyle during the epidemic to ensure good mental health status.

Our study also indicates that students with a contact history of similar infectious diseases are more likely to have mental health issues because this experience may cause students to worry about whether they have been infected, and medical students are more likely to be exposed to similar diseases in clinical work. Previous studies also suggested a significant association with anxiety for people whose contact histories included contact with an individual with suspected COVID-19 or with infected materials [31].

This study indicates that students who exercised during the epidemic outbreak were less likely to have mental health issues. Studies have suggested that physical exercise is associated with greater cardiovascular fitness, improved muscle strength and endurance, and reduction of depression and anxiety [45]. Students should continue to exercise during the epidemic to ensure good mental health. Unexpectedly, a high level of concern about COVID-19 was less likely to be associated with mental health issues owing to the dissemination of positive scientific information on Chinese media’s public emergencies. Therefore, it is recommended to pay suitable attention to the news, especially the good news related to the epidemic, and such behaviors are beneficial to maintain a good attitude during the outbreak of COVID-19.

Previous studies have suggested that female and older students are more likely to have mental health symptoms [11,12]; women and older people have been found to experience more significant psychological impact and higher stress levels, anxiety, and depression [31]. These findings are inconsistent with our research results; because older students experienced SARS in 2003, they may have a more comprehensive understanding and a higher level of awareness of COVID-19 and may be less likely to have mental symptoms during the epidemic.

For family and society, these risk variables that cause mental health issues are key factors for early judgment of university students’ psychological problems, and the results also provide the theoretical basis for formulating intervention measures. Schools, families, and the government should provide more care and support to university students during the epidemic.

Limitations

Given the limited available resources and the time of the COVID-19 outbreak, the study adopted the snowball sampling strategy, which is not based on randomly selected samples. Additionally, the researchers did not conduct a prospective study that would provide a specific measure to support the needs of targeted public health initiatives.

Conclusions

During the outbreak of COVID-19, some university students experienced mental symptoms. Past medical history, contact history of similar infectious disease, and compulsive behaviors were risk factors for mental health issues. Older age of the students, regular daily life, and exercise during the epidemic outbreak were protective factors against mental health issues. A high level of concern (>1 hour per day) about COVID-19 was also a protective factor.

These findings are beneficial for identifying the groups of university students at risk for possible mental health issues, and they provide a theoretical foundation for the formulation of relevant interventions so that universities and families can prevent or intervene in the development of mental health issues among students at the early stage of the disease. Likewise, the findings are essential for education and public health epidemic prevention. In short, students require more attention, help, and support from society, families, and universities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data and materials used in this study are available upon request from the author.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the China Medical University novel coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control research project (2020-12-11); however, the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the project. The study was also supported by the Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2020-MS-155), Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (2013-1792), Fund for Scientific Research of The First Hospital of China Medical University (FSFH201722), and National Science Foundation of China (72074104). The researchers are grateful for the support of several organizations.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- OR

odds ratio

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SAS

Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

- SDS

Self-Rating Depression Scale

- YBOCS

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: YB, HQJ, and YW designed the web-based questionnaires. YB, XZ, KHL, DZ, SYZ, YQS, and FZ organized the data. XZ, XS, and QQZ analyzed and verified the data. XZ wrote the first draft. XS revised and polished the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishiura H, Jung S, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Yang Y, Hayashi K, Kobayashi T, Yuan B, Akhmetzhanov AR. The extent of transmission of novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, 2020. JCM. 2020 Jan 24;9(2):330. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The latest situation of the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic as of 24:00 on July 31. Webpage in Chinese. National Health Commission, People's Republic of China. 2020. Jul 31, [2021-07-14]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yjb/s7860/202008/96184996b6724df787ea9380dfdc88bf.shtml.

- 4.Mahase E. China coronavirus: WHO declares international emergency as death toll exceeds 200. BMJ. 2020 Jan 31;:m408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallick S. Global Covid-19 cases top 83.9 million, deaths over 1.82 million. Odisha TV. 2021. Jan 02, [2021-07-14]. https://odishatv.in/coronavirus/global-covid-19-cases-top-83-9-million-deaths-over-1-82-million-505942.

- 6.Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;7(4):300–302. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall R, Hall R, Chapman M. The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):446–52. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18774428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin G, Potts H, Michie S. The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technol Assess. 2010 Jul;14(34):183–266. doi: 10.3310/hta14340-03. doi: 10.3310/hta14340-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, Jambai M, Koroma AS, Muana AT, Hann K, Eaton J, Martin S, Nellums LB. Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Mar 01;94(3):210–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26966332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim K, Huak Chan Y, Chong PN, Chua HC, Wen Soon S. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res. 2010 Feb;68(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20105703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Li-Yu, Wang Jie, Ou-Yang Xiao-Yong, Miao Qing, Chen Rui, Liang Feng-Xia, Zhang Yang-Pu, Tang Qing, Wang Ting. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med. 2021 Jan;77(3):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32593614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gómez-Salgado Juan, Andrés-Villas Montserrat, Domínguez-Salas Sara, Díaz-Milanés Diego, Ruiz-Frutos C. Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 02;17(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113947. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17113947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ping W, Zheng J, Niu X, Guo C, Zhang J, Yang H, Shi Y. Evaluation of health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020 Jun 18;15(6):e0234850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234850. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Özdin Selçuk, Bayrak Özdin Şükriye. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 08;66(5):504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0020764020927051?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, Sarin SK. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: An online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Al-Rousan R, Alwafi H, Alrawashdeh HM, Ghoul I, Abidine A, Bokhary MA, Al-Hadithi HT, Ali D, Abuthawabeh R, Abdelwahab GM, Alhartani YJ, Al Muhaisen H, Dagash A, Alyami HS. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2020 Aug;10(8):e01730. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1730. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Xia Q, Xiong Z, Li Z, Xiang W, Yuan Y, Liu Yaya, Li Zhe. The psychological distress and coping styles in the early stages of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in the general mainland Chinese population: a web-based survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233410. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G. How bad is it? Suicidality in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020 Dec;50(6):1241–1249. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12655. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32589799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, Yang J, Yang L, Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020 Apr 20;26 doi: 10.12659/msm.924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Feng X, Wang X, van IJzendoorn MH. Coping with COVID-19: exposure to COVID-19 and negative impact on livelihood predict elevated mental health problems in Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 29;17(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113857. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17113857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung GM, Lam T, Ho L, Ho S, Chan BHY, Wong IOL, Hedley AJ. The impact of community psychological responses on outbreak control for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Nov;57(11):857–63. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.857. https://jech.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Ansari W, Labeeb S, Moseley L, Kotb S, El-Houfy A. Physical and psychological well-being of university students: survey of eleven faculties in Egypt. Int J Prev Med. 2013 Mar;4(3):293–310. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23626886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan J, Liu X, Shao G, Qi J, Li Y, Pan W, Hambly BD, Bao S. The epidemiology of reverse transmission of COVID-19 in Gansu Province, China. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;37:101741. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101741. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32407893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Tsang KW, Sham PC, Chua SE, Wong JG. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2007 Apr 23;52(4):241–7. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HFK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004 Oct;34(7):1197–204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grace SL, Hershenfield K, Robertson E, Stewart DE. The occupational and psychosocial impact of SARS on academic physicians in three affected hospitals. Psychosomatics. 2005 Sep;46(5):385–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.385. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16145182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971 Nov;12(6):371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zung WWK. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965 Jan 01;12(1):63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman WK, Price L H, Rasmussen S A, Mazure C, Fleischmann R L, Hill C L, Heninger G R, Charney D S. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov 01;46(11):1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 Jul;10(7):1206–12. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15324539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 06;17(5) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, Feng J, Qiao M, Jiang R, Bi J, Zhan G, Xu X, Wang L, Zhou Q, Zhou C, Pan Y, Liu S, Zhang H, Yang J, Zhu B, Hu Y, Hashimoto K, Jia Y, Wang H, Wang R, Liu C, Yang C. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Aug;88:916–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32169498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students' mental health in the United States: interview survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Sep 03;22(9):e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e21279/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Sep 17;22(9):e22817. doi: 10.2196/22817. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e22817/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mira JJ, Cobos A, Martínez García Olga, Bueno Domínguez María José, Astier-Peña María Pilar, Pérez Pérez Pastora, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Perez-Jover V, Fernandez C, Vicente MA, Lahera-Martin M, Silvestre Busto C, Lorenzo Martínez Susana, Sanchez Martinez A, Martin-Delgado J, Mula A, Marco-Gomez B, Abad Bouzan C, Aibar-Remon C, Aranaz-Andres J, SARS-CoV-2 Second Victims Working Group An acute stress scale for health care professionals caring for patients with COVID-19: validation study. JMIR Form Res. 2021 Mar 09;5(3):e27107. doi: 10.2196/27107. https://formative.jmir.org/2021/3/e27107/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan BY, Chew NW, Lee GK, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LL, Zhang K, Chin H, Ahmad A, Khan FA, Shanmugam GN, Chan BP, Sunny S, Chandra B, Ong JJ, Paliwal PR, Wong LY, Sagayanathan R, Chen JT, Ng Ayy, Teoh HL, Ho CS, Ho RC, Sharma VK. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 18;173(4):317–320. doi: 10.7326/m20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32229390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleiman EM, Yeager AL, Grove JL, Kellerman JK, Kim JS. Real-time mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students: ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Dec 15;7(12):e24815. doi: 10.2196/24815. https://mental.jmir.org/2020/12/e24815/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Copeland WE, McGinnis E, Bai Y, Adams Z, Nardone H, Devadanam V, Rettew J, Hudziak JJ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Jan;60(1):134–141.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33091568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolatov AK, Seisembekov TZ, Askarova AZ, Baikanova RK, Smailova DS, Fabbro E. Online-learning due to COVID-19 improved mental health among medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2020 Nov 18;31(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01165-y. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33230424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Zhao J, Ma Z, McReynolds LS, Lin D, Chen Z, Wang T, Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Fan F, Liu X. Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a 2-wave longitudinal survey. J Affect Disord. 2021 Feb 15;281:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reznik A, Gritsenko V, Konstantinov V, Yehudai M, Bender S, Shilina I, Isralowitz R. First and second wave COVID-19 fear impact: Israeli and Russian social work student fear, mental health and substance use. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021 Feb 02;:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00481-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33551690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun J, Li Z, Buys N, Storch EA. Correlates of comorbid depression, anxiety and helplessness with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2015 Mar 15;174:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velten J, Bieda A, Scholten S, Wannemüller André, Margraf J. Lifestyle choices and mental health: a longitudinal survey with German and Chinese students. BMC Public Health. 2018 May 16;18(1):632. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5526-2. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.da Cunha Joel, Maselli Luciana Morganti Ferreira, Stern Ana Carolina Bassi, Spada Celso, Bydlowski Sérgio Paulo. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on lipid metabolism of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: old and new drugs. World J Virol. 2015 May 12;4(2):56–77. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v4.i2.56. https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v4/i2/56.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials used in this study are available upon request from the author.