Abstract

We report the discovery of a novel class of compounds that function as dual inhibitors of the enzymes neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (nSMase2) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Inhibition of these enzymes provides a unique strategy to suppress the propagation of tau pathology in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We describe the key SAR elements that affect relative nSMase2 and/or AChE inhibitor effects and potency, in addition to the identification of two analogs that suppress the release of tau-bearing exosomes in vitro and in vivo. Identification of these novel dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors represents a new therapeutic approach to AD and has the potential to lead to the development of truly disease-modifying therapeutics.

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent age-related neurodegenerative disorder and, currently, there are no effective disease-modifying therapies available for the treatment of AD. The number of AD cases in the US is ~5.8 million patients and this number is expected to rise to 50 million by 2050. The estimated global economic costs of AD and related dementias are predicted to reach $2 trillion by the year 2030.1

AD brain tissue is characterized by the presence of senile plaques composed mainly of aggregated amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) comprised of pathological forms of the microtubule-stabilizing protein tau, chronic neuroinflammation, and loss of neurons.2 Clinically, it is thought that the underlying mechanisms of disease are initiated as early as 20 years before the onset of signs and symptoms. During this asymptomatic period, proteopathic proteins are believed to accumulate, leading to structural alterations and the neuronal dysfunction and loss that leads frequently to nild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI then progresses to full-blown AD-related memory deficits, decline of other cognitive skills, and in advanced AD, the inability to participate in activities of daily living.3

While the exact mechanisms of disease progression have not been fully elucidated, it is thought that increased Aβ production at the synapse and/or impaired clearance results in synaptic loss. Contemporaneously and in conjunction with Aβ accumulation, there is hyperphosphorylation and oligomerization of tau that eventually leads to neuronal toxicity, NFT formation, and neuronal cell death. Diseased neurons can release these toxic phosphorylated forms of tau (p-tau) in proteopathic seeds, which can then be taken up by surrounding or interconnected neurons, leading to templating and propagation of the pathological aggregates in prionlike fashion. The propagation of the disease follows a spatiotemporal pattern with Aβ plaques first appearing in the basal forebrain and then in the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes of the cortex. NFTs form in the locus coeruleus and in the allocortex of the medial temporal lobe.4 Both Aβ and tau pathologies spread through the brain during disease progression.2

Given the importance of tau, significant attention is now being paid to the mechanisms of pathological tau spread in AD with the goal of identifying targets for novel therapies to prevent disease progression.5 Historically, Aβ pathology has been thought to be causative in AD,6,7 but multiple clinicopathological evaluations, as well as recent in vivo imaging studies, suggest that the cognitive status of AD patients correlates most closely with region-specific brain atrophy and distribution of the hyperphosphorylated and aggregated pathological forms of tau that lead to the formation of NFTs.8–11 Longitudinal studies have confirmed that propagation of tau pathology correlates significantly with cognitive decline.12,13 These data suggest that suppression of propagation of tau pathology in AD may have a disease-modifying effect.

Prompted by the findings described above, we undertook a screening effort to identify inhibitors of tau propagation. As will be discussed below, this led to the discovery of dual inhibitors of two enzymes: neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) and acetylcholine esterase (AChE), a key enzyme implicated in AD. In our in vitro studies, the identified dual inhibitors prevented the spreading of tau in cell culture systems using assays we have previously described.14

nSMase2 is an enzyme responsible for hydrolysis of sphingomyelin to ceramide/phosphatidylcholine and has been implicated in the spread of AD pathology. Pharmacological inhibition or genetic depletion of nSMase2 has been shown to suppress progression of both Aβ and tau pathology in animal models. 15–17 nSMase2 activity plays an important role in normal brain function, but its activity increases with age, leading to dysregulation in sphingomyelin turnover.18–22 There is overactivation of nSMase2 in AD and brain ceramide levels have been found to be elevated in AD patient cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), compared to age-matched control subjects.23 The ceramide/sphingomyelin imbalance is greater in individuals that express apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), the major genetic risk factor for sporadic, late onset AD.24 nSMase2 is a key enzyme involved in biogenesis of brain exosomes through the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT)-independent pathway.25 Brain exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicle (EV), that are 40–150 nm in diameter and are released by brain cells when multivesicular endosomes fuse with the plasma membrane.25,26 They are involved in normal brain function, but a subset produced by the ESCRT-independent pathway involving nSMase2 has been shown to carry disease-propagating proteopathic seeds, such as tau oligomers, in AD.14,15,17,27 Tau oligomers have been found to be associated with neuronal exosomes in both cell culture medium and transgenic AD/tauopathy model brain tissue, as well as in AD patient plasma and CSF.15,28–33

Despite recent progress, the current armamentarium of nSMase2 inhibitors has poor drug-like properties and oral brain permeability.34,35 Thus, our initial goal was to identify nSMase2 inhibitors that overcome these limitations for the development of preclinical candidates for AD. Using an nSMase2 inhibitor screening assay, we identified a novel furoindoline compound as a “validated hit”. Further structural alterations of this initial hit generated compounds that resulted in the identification of novel dual inhibitor analogs that not only inhibit nSMase2 activity but also inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme activity and suppress tau propagation.

AChE inhibitors (AChEIs) are currently one of only two classes of FDA-approved AD therapeutics; they have demonstrated amelioration of symptoms in AD, being most effective in mild and moderate AD.36 Inhibition of AChE leads to increased levels of acetylcholine (ACh) at the synapse and in brain parenchyma and provides support for cholinergic synaptic plasticity even during progressive loss of cholinergic innervation from the basal forebrain.37 However, AChEI treatment only provides short-term benefits in AD and does not block the progression of the disease.

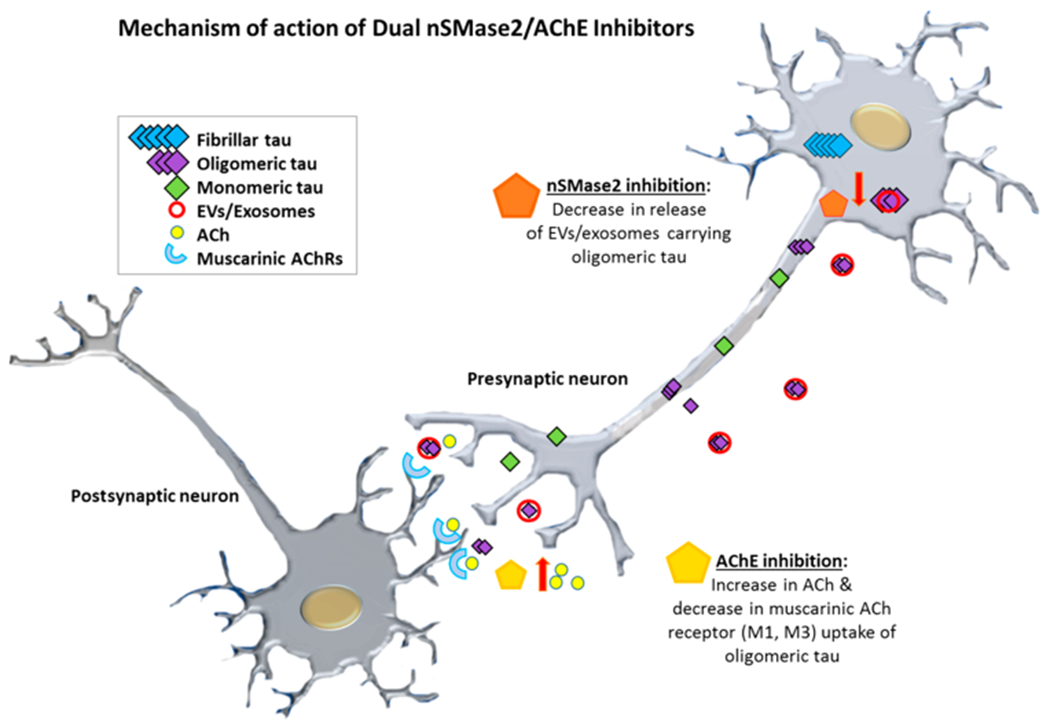

The dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors we describe herein represent a new therapeutic paradigm enabling target engagement by a single agent of two enzymes in the brain that play a role in the spread of tau pathology.38 This promising approach could lead to an effective treatment for AD. These agents have the potential to be disease-modifying by suppressing disease progression through exosome-mediated tau propagation, while also providing symptomatic relief through support of ACh-mediated cognitive enhancement. Interestingly, in mild to moderate AD, there is significantly decreased cholinergic activity and high levels of p-tau in CSF-derived exosomes; thus treating patients in these stages of the disease with dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors could be highly beneficial.33 We propose a mechanism of action for these dual inhibitors involving nSMase2-mediated suppression of tau oligomer release in brain exosomes by presynaptic neurons and increased ACh levels at the synapse through AChE inhibition, along with the suppression of tau oligomer uptake through ACh receptors by postsynaptic neurons.38

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening for and Optimization of Selective nSMase2 and Dual nSMase2/AChE Inhibitors.

We initiated the present study by screening a small molecule compound library for effects on nSMase2 activity. The ~70 compound library was largely comprised of fused indolines we had prepared previously through interrupted Fischer indolization methodology that have structural resemblance to phenserine and known AChE inhibitors. Using an Amplex Red neutral sphingomyelinase enzyme activity assay several hits were identified that inhibited ≥60% nSMase2 activity at a concentration of 50 μM, as shown in the scatterplot (Figure 1a). The known nSMase2 inhibitor cambinol14 was used as a positive control for the screening assay. After retesting, one hit (Figure 1a) was validated at 50 μM and selected for further hit-to-lead optimization.

Figure 1.

Screening and identification of novel dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors: a) nSMase2 inhibitor screening using the Amplex Red-coupled assay revealed several hits that inhibited activity ≥60%; b) hit-to-lead optimization of the validated hit shows removal of the nitrogen group from the furoindoline aryl ring (red arrow), and addition of nitrogen to the carbamate phenyl ring at either the 3 or 4 positions (blue arrow) results in enhanced potency for nSMase2 inhibition and varied AChE inhibition; c) dose–response analysis for compounds 1, 8, and 11 in the nSMase2 assay; and d) dose𠄓response analysis for compounds 1, 8, and 11 in the AChE assay.

Optimization efforts led to the synthesis and evaluation of analogs. Our synthetic approach to the validated hit and analogs will be described subsequently, but a summary of our optimization effort leading to key dual inhibitor analogs 8 and 11 is shown in Figure 1b. Given the structural similarity between the validated hit and known AChE inhibitor phensvenine (1) we initially prepared this analog to check if it was also an nSMase2 inhibitor. Dose–response analysis revealed that phensvenine (1) indeed has nSMase2 inhibitory activity (Figure 1c) but is a more potent inhibitor of AChE with an IC50 = 0.5 μM (Figure 1d). In contrast, the dual inhibitors 8 and 11 were more potent nSMase2 inhibitors (IC50 = 0.5 μM) with varying AChE inhibitory activity (Figure 1c and 1d). Interestingly, replacement of the oxygen in the furoindoline ring of phensvenine (O > N–CH3), as seen in phenserine ,a known potent AChE inhibitor, results in the loss of nSMase2 inhibitory activity (IC50 > 50 μM). Posiphen, the (+)-enantiomer of phenserine, is reported to be a weak AChE inhibitor and did not show detectable nSMase2 inhibitor activity (IC50 > 50 μM).39 We therefore focused on the (−)-enantiomer for the dual inhibitor optimization effort.

The synthesis of the validated hit and analogs was made possible by using the interrupted Fischer indolization reaction and variants thereof.40 As an example, the interrupted Fischer indolization route to (−)-phensvenine (1) is shown in Scheme 1. Treatment of aryl hydrazine 17 and lactol 18 with acetic acid furnished furoindoline 19 in 67% yield. Subsequent N-methylation provided 23. At this stage, the enantiomers could be resolved using chiral SFC. As depicted for the (−)enantiomer, O-deprotection was achieved using BBr3, thus furnishing (−)-26. Lastly, treatment with NaH and phenylisocyanate furnished (−)-phensvenine (1). It should be noted that (−)-enantiomers were specifically targeted given the known stereospecificity of phenserine for AChE inhibition.39,41

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (−)-Phensvenine (1)

The synthetic route was readily amenable to the synthesis of analogs, particularly by exploiting intermediate (−)-26 as a means to access different carbamate substitution patterns. Scheme 2 provides an example, in the context of the synthesis of analog (−)-8. Alcohol (−)-26 readily underwent reaction with 29 to furnish carbonate (−)-30. Upon treatment with 4-aminopyridine (32), (−)-8 was obtained in 61% yield. The syntheses of other carbamate analogs are provided in the SI.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Furoindoline Analog (−)-8

Scheme 3 shows the routes used to prepare two analogs bearing substitution on the furoindoline ring. Interrupted Fischer indolization using hydrazine 20 and lactol 21 proceeded smoothly to give 22 as a mixture of diastereomers in racemic form. Upon methylation, diastereomers 24 and 25 were accessed and could be separated by silica gel chromatography. Each diastereomer was then elaborated through a sequence involve separation by chiral SFC, demethylation, and carbamate formation. This unoptimized synthetic sequence delivered (−)-9 and (−)-10, respectively, for initial biological evaluation.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Furoindoline Analogs (−)-9 and (−)-10

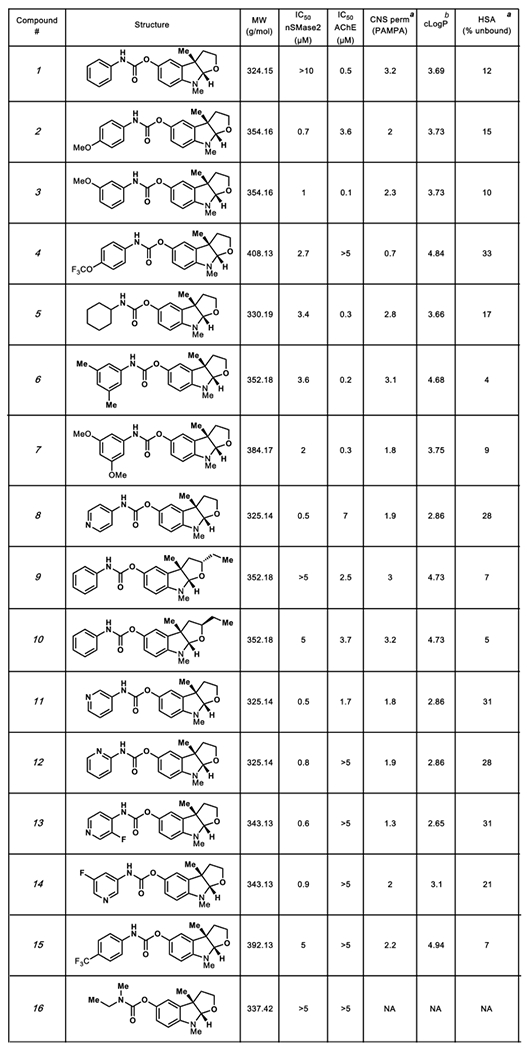

In total, 16 analogs were prepared as part of the optimization efforts. The structures of these analogs, dose–response analysis results, predicted brain permeability data, and binding efficiency to human serum albumin (HSA) are shown in Table 1. Our SAR analysis reveals structural elements in this series required for enhanced nSMase2 and/or AChE inhibition. Substitutions in the carbamate phenyl ring pointed to a critical role for positions 3 and 4 as key control elements for nSMase2 and/or AChE inhibition. Substitution at the 4-position leads to increased selectivity for nSMase2 inhibition (such as for compounds 2, 4, and 8). In contrast, substitution at the 3-position leads to increased selectivity for AChE inhibition (such as 3 and 11). Introduction of electron donating groups (3, 6, and 7) at position 3 increased potency of AChE inhibition, while an electron withdrawing group (such as in 14) resulted in decreased potency. Importantly, replacement of the phenyl ring with a pyridyl ring in the carbamate moiety generally decreased potency of AChE inhibition and markedly enhanced potency for nSMase2 inhibition (e.g., 8, 11, 12). Most of the analogs (except 4) showed high predicted brain permeability by in silico StarDrop analysis and in a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA). A low degree of binding to human serum albumin (HSA) was measured for most of the compounds, especially 8, 11, 12, and 13.

Table 1.

Structure and Characteristics of Carbamate Furoindoline Analogs

|

Measured values, see details in the SI.

Calculated value using StarDrop software.

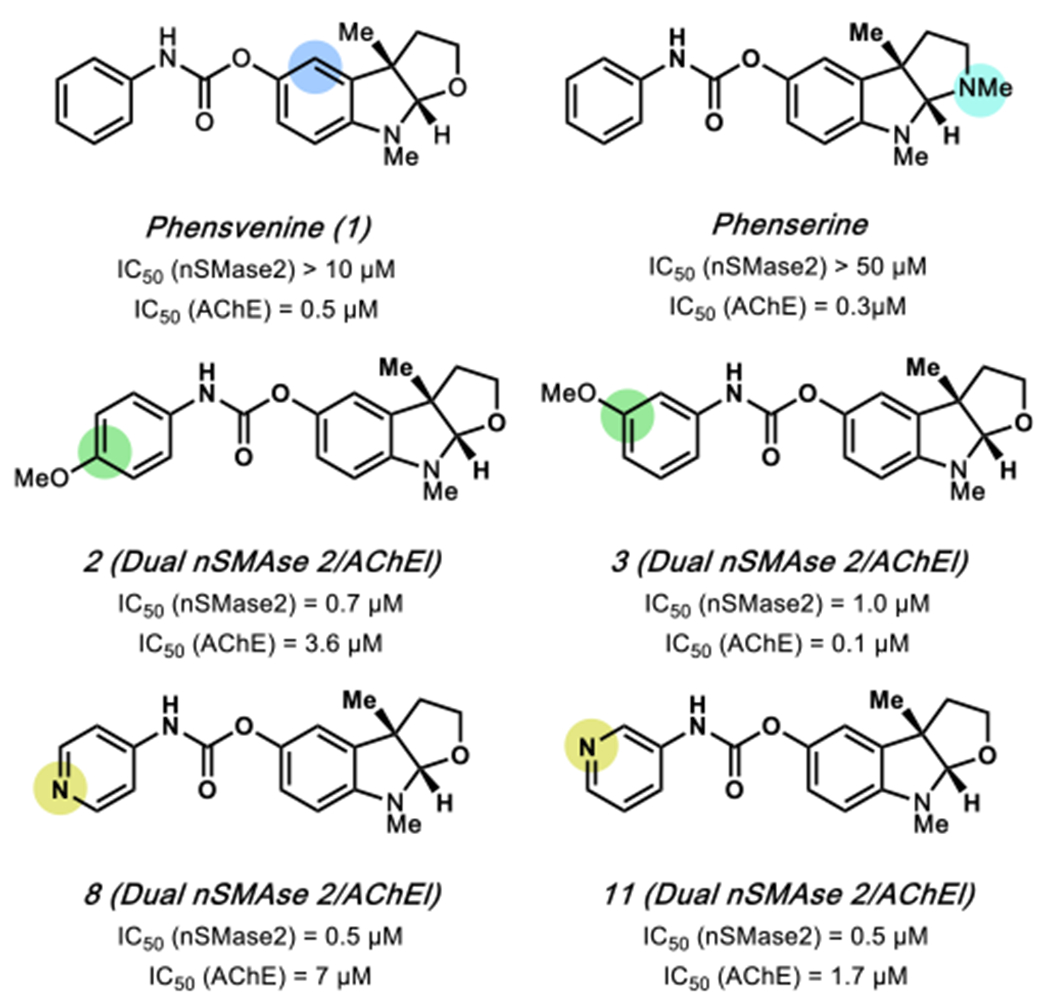

A summary of the dual nSMase2/AChE inhibition SAR from our optimization efforts is summarized in Figure 2. Key points are as follows: (1) replacement of nitrogen in the furoindoline ring of the validated hit yields 1 (phensvenine), which is a dual inhibitor showing weak nSMase2 inhibition (IC50 >10 μM) but potent AChE (IC50 = 0.5 μM) inhibition;42 (2) phenserine, a commercially available potent AChE inhibitor, displays loss of nSMase2 inhibitory activity (IC50 (not depicted) > 50 μM); (3) substitution at the 3-position of the carbamate ring favors enhanced AChE inhibition as seen in compound 3 compared to compound 2; (4) the 4-pyridyl ring in the carbamate group leads to 8, a dual inhibitor with ~14-fold increased selectivity for nSMase2 inhibition (IC50 = 0.5 μM) over AChE inhibition (IC50 = 7 μM); and (5) the 3-pyridyl carbamate compound 11 was a dual inhibitor with ~3-fold increased selectivity for nSMase2 (IC50 = 0.5 μM) and AChE (IC50 = 1.7 μM) inhibition. The mode of inhibition by the dual inhibitors (shown below) of both enzymes allows for comparison of dual activity using IC50 values.39,41 Based on the SAR, the two dual inhibitors, 8 and 11, with 10- and 3-fold selectivity for nSMase2 inhibition over AChE, respectively, were further evaluated in in vitro and in vivo assays for exosomal tau release.

Figure 2.

Key structure–activity relationship (SAR) control elements for inhibition of nSMase2 (blue highlight) and AChE (yellow or green highlight) activity are indicated.

Mechanism of AChE and nSMase2 Inhibition by the Novel Furoindoline Compounds.

To determine the type of nSMase2 inhibition by compounds 8 and 11, kinetics assays were performed. As shown in Figures 3a and 3b, increasing concentrations of compounds 8 and 11 resulted in decreasing Km (the Michaelis constant) values as well as concomitant decreases in Vmax (the maximum rate) indicative of an uncompetitive mechanism of inhibition of nSMase2.43 Thus, it can be concluded that both compounds bind to the enzyme distal to the active site and can inhibit enzyme–substrate cleavage.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of nSMase2 inhibition by compounds 8 and 11. Kinetics of enzyme inhibition by compounds 8 (a) and 11 (b) are shown. The rate of the reaction is plotted against substrate concentration at four different concentrations of the inhibitors; corresponding values for Vmax and Km are presented in the tables below the graphs. c) Modeling of 8 and 11 (green) binding to the catalytic domain of nSMase2 predicts compound binding preferably near the DK-switch site than the substrate binding site. d) Molecular surface representation of the nSMase2 catalytic domain with 8 and 11 (green) bound near the DK-switch; the color representations are blue for positive charge, red for negative charge, and white for neutral charge. e) The nSMase2 residues (yellow) within a 5 Å radius surrounding inhibitors 8 and 11 (green); H-bonding between the inhibitor and nSMase2 is shown by dashed lines (black).

Molecular docking analysis (see the SI for details) was performed using a recently published crystal structure of the nSMase2 catalytic domain (pdb: 5UVG).44 We found that both 8 and 11 could bind to nSMase2 at the distal DK-switch (Asp-Lys) site away from the substrate sphingomyelin site and thus, in concordance with the kinetic analysis, could be uncompetitive inhibitors of the enzyme through modulation of the DK-switch. This is similar to what we have previously published with the known nSMase2 inhibitor cambinol, which was also shown by molecular docking and simulation to bind the nSMase2 catalytic domain in the DK-switch region and prevent enzyme activation by likely keeping the switch in the “off” position.14 Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to determine the binding free energy of compound 8 binding to nSMase2. Compound 8 stays at the DK-switch site of nSMase2 through the 50 ns simulation with an estimated binding energy of −14.3 kcal/mol. An AMBER16 package was used to perform the MD simulation.

Kinetic studies of AChE inhibition by phenserine were shown to be in a mixed type manner (competitive/uncompetitive), and we assumed that likewise the dual inhibitor compounds 8 and 11 would bind to the active site of AChE and show mixed inhibition.41,42

In Vitro Inhibition of Tau Seed Propagation by Dual nSMase2/AChE Inhibitors.

We previously developed a cell culture system based on a well-known tau RD biosensor cell line (tau biosensors) for testing inhibitors of tau propagation.14 Using known nSMase2 inhibitors cambinol and GW4869, we have demonstrated the role of the nSMase2-dependent pathway of EV biogenesis in tau transmission from donor to recipient cells in this non-neuronal cell model using two different in vitro assays–the Donor plus Recipient (D+R) assay and the EV-mediated transfer (EMT) assay.14

The principles of the D+R and EMT assays are presented in schematic form in Figures 4a and 4b, respectively. Our data demonstrates that treatment with 8 or 11 at a concentration of 20 μM significantly suppresses tau seed transfer from donor to recipient cells in the D+R and EMT assays (Figures 4a, 4b and Supplementary Figure 10). Shuttling by tau-bearing EVs is not the only pathway of tau seed transfer between cells in vivo or when donor and recipient cells are growing together in vitro, as in the D+R assay. In contrast, the EMT assay lets us isolate the effect of the inhibitors on EV-mediated tau seed transmission, which can explain the profound difference in the magnitude of the FRET fluorescence density by dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitor 11 between the assays–19.5% decrease from dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treated cells in the D+R assay and 41.3% decrease in the EMT assay.

Figure 4.

Dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors 8 and 11 suppress tau propagation from donor to recipient cells in vitro. The assay scheme for each assay is presented at the top of the figure. a) Donor plus recipient (D+R) assay results are shown. Compounds 8 and 11 at a concentration of 20 μM or a corresponding volume of DMSO were added to the D+R cultures for 48 h. Levels of the FRET signal were analyzed in recipient cells using flow cytometry. Combined data from three independent experiments are presented. b) EV-mediated tau seed transfer (EMT) assay results are shown. Compounds 8 and 11 at 20 μM concentration or DMSO were added to donor cell culture medium, and then donor cell-derived EVs were purified and transfected to recipient cells. Levels of the FRET signal were analyzed in recipient cells using flow cytometry. Four technical replicates were used for each experimental condition. Combined data from three independent experiments is presented. The histograms represent integrated FRET density per each treatment group (mean ± SEM). c) Size distribution and concentrations of the donor-derived EV samples were analyzed by Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS). d) Donor-derived EVs were imaged using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The size bar is 100 nm. e) Western blot (WB) representative images for exosomal markers are shown. The same volume of EV fractions derived from a similar number of donor cells or control tau biosensor cells treated with Lipofectamine 2000 (Control) were loaded per well and probed against exosomal markers CD63, CD81, and Syntenin-1. Densitometry analysis is shown below the WB image. Statistics were performed using One-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni, and the Holm multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis: * p < 0.05, **<0.01.

We characterized EVs purified from the seeded donor cells growing in the presence of our dual inhibitor compounds 8 and 11 or DMSO control. Successful purification of EVs was confirmed by tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) (Figure 4c), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 4d), and Western blotting analysis with known exosomal markers (Figure 4e). Treatment with dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors 8 or 11 did not affect EV size distribution but decreased the concentrations of exosomal-type small EVs (Figure 4c). Levels of exosomal markers CD63, CD81, and syntenin-1 were reduced in EVs purified from 8 and 11 treated cells in comparison with the DMSO treated donors (Figure 4e). Relatively high suppression of tau transfer by 11 compared to 8 in the EMT assay may be related to the greater AChE inhibitory activity of 11 in conjunction with its nSMase2 inhibition and the role of dual inhibitory activity in exosome-mediated transfer of tau seeds.38 Interestingly, in pilot testing using the (+) enantiomer of 8 and 11 in the EMT assay, we did not see any suppression of EV-mediated tau seed transfer when compared to the (−) enantiomer.

Cell viability and/or rate of proliferation may have an effect on tau seed transfer from donor to recipient cells through different mechanisms. Thus, we evaluated effects of tau seeding and treatment with nSMase2/AChE inhibitors on donor cell number and viability. Twenty-four hour exposure to AD human brain synaptosomal extracts decreased the rate of the donor cell survival in the next passage compared to cells treated with lipofectamine 2000 (Supplementary Figure 11). We have not determined the specific mechanisms of cell death in tau-seeded donor cultures. It is possible that a subset of tau-bearing EVs affected by nSMase2 inhibitors contain apoptotic exosome-like vesicles (AEVs) that–in contrast to apoptotic bodies–represent a subtype of exosomes originating from multivesicular endosomes (MVE) at the early apoptotic phase. AEV biogenesis is controlled by the ESCRT-independent sphingosine1-phosphate (S1P)/S1PRs signaling pathway and can be partially inhibited by the nSMase2 inhibitor GW4869.45 Interestingly, AChE inhibitors are known to protect different cell types, including HEK293T, from apoptosis,46 and thus dual inhibitor 11 with greater AChE inhibition could potentially indirectly suppress AEV production. However, treatment of donor cells with 11 for 48 h did not affect donor cell numbers or survival compared to DMSO or to compound 8 treated donor cells (Supplementary Figures 11a and 11b). We also hypothesize that other factors may contribute to the greater effect of 11 on tau seed transfer in the EMT assay. A recent report suggests that intracellular uptake of tau can be mediated by the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) M1 and M3.38 Thus, accumulation of tau oligomers in the synapse may exacerbate the cholinergic deficit in AD through suppression of ACh uptake via mAChRM1/M3 receptors on postsynaptic terminals. Based on similar reasoning, inhibition of AChE could have a direct effect on tau seed uptake through the increased levels of ACh in the synapse and postsynaptic M1/M3 receptor occupancy.

Our preliminary experiments at 20 μM using rivastigmine, a potent AChE (but with no nSMase2 activity) inhibitor, reveals that inhibition of AChE may partially suppress EV-mediated transfer and uptake of tau seeds by recipient cells (Supplementary Figures 12). We have previously published on cambinol, an nSMase2 inhibitor (IC50 = 7.7 μM but no AChE activity), that shows inhibition of tau seed transfer in the EMT assay.14 The novel dual inhibitors 8 and 11 have both nSMase2/AChE inhibitory activities in the same molecule and show suppression of tau transfer (Figures 4b). Thus, these dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors 8 and 11 are agents that could be developed to efficiently target both enzymes in the brain and suppress tau propagation.

Brain Pharmacokinetics for Lead Compounds.

Our goal was to identify brain permeable dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitor analogs for further testing. We therefore performed pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis on the leads 8 and 11 to determine brain permeability using wild-type mice. The compounds, whose brain permeability have not been previously described, were subcutaneously (SQ) injected at a relatively high dose of 20 mg per kg of body weight (mpk) to determine brain penetrance. Brain and plasma samples were collected 1, 2, and 4 h after dosing. Our PK analysis revealed that 8 and 11 reached peak brain levels (Cmax) around 1 h after SQ dosing, and brain levels were detectable for both compounds 4 hours after injection (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Pharmacokinetic analysis for lead compounds 8 and 11. a) Mice were subcutaneously (SQ) injected with 20 mg/kg of compound 8 or 11; animals were sacrificed 1, 2, and 4 h after dosing (n = 1 animal per time point). b) Mice were dosed as in (a), but n = 6 per compound and sacrificed 1 h after dosing. Compound levels in brain tissue were analyzed using a LC-MS/MS method.

To carefully evaluate brain compound levels at the Cmax (1 h) time point, 20 mpk SQ dosing of compounds 8 and 11 was performed again using 6 mice per group. The average brain level of the compounds at the peak was equal to 61 ng/g (~0.2 μM) and 262 ng/g (~0.8 μM) for compounds 8 and 11, respectively (Figure 5b). This data confirmed good brain permeability of the lead compounds as was predicted by in silico and PAMPA analysis described earlier (Table 1). Compound 11 showed higher average brain levels compared to 8, and the brain levels corresponded to ~2-fold IC50 for nSMase2 and ~0.5-fold for AChE.

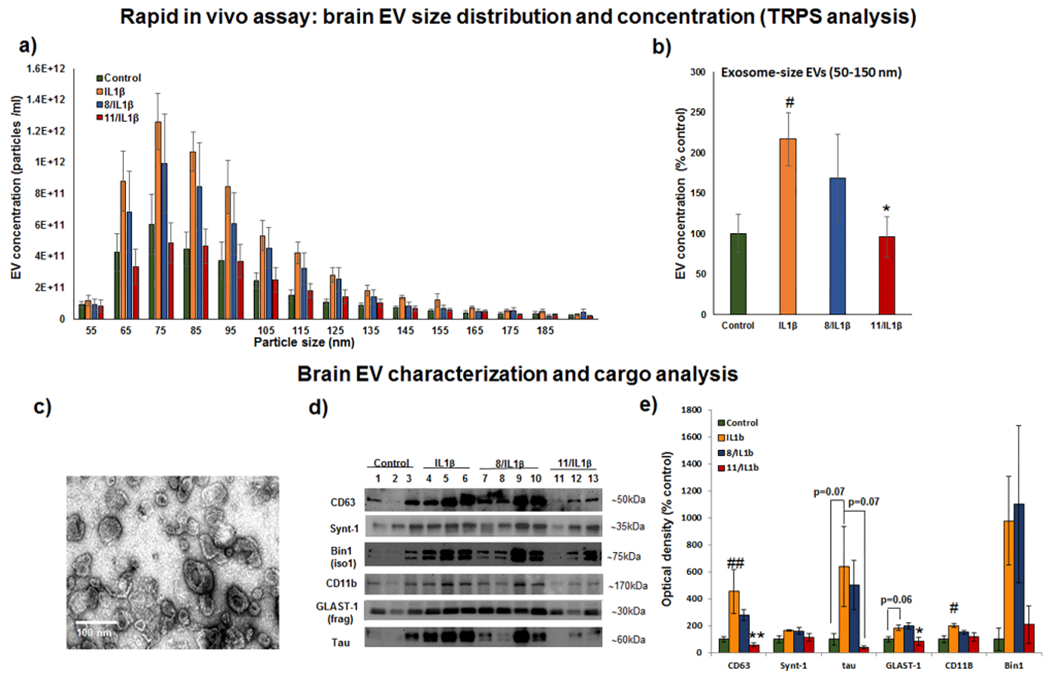

Inhibition of Brain EV Release by the Dual nSMase2/AChE Inhibitors in a Rapid in Vivo Assay.

The chronic inflammation that is reported in AD and tauopathy models is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in brain parenchyma, including interleukin 1β (IL1β), known to induce nSMase2 activity through the IL1-Receptor 1 (IL1-R1).47 Neuroinflammation and upregulation of IL1β signaling is linked with an early stage of tauopathy development; blocking of IL1β signaling in the 3xTg mouse AD model attenuates tau pathology and rescues cognition.48–50 It was demonstrated that striatal injection of IL1β to wild-type mice induced release of astrocyte-derived EVs into the blood, resulting in peripheral acute cytokine responses51 which can be suppressed by pretreatment with nSMase2 inhibitors.34,35

In order to rapidly test our dual nSMase2 inhibitors in vivo, we used the Tau P301S (PS19 line) tauopathy mouse model.48 For our in vivo assay there were 4 groups: group I (control) received SQ injection of vehicle (DMSO) and intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of another vehicle (0.0006% BSA in PBS, pH 7.4) an hour after SQ treatment; group II (IL1β) received SQ injection of vehicle and unilateral ICV injection of 0.2 ng of IL1β an hour later; group III (8/IL1β) received SQ treatment with 20 mg/kg of 8 and ICV injection of 0.2 ng of IL1β; and group IV received SQ treatment with 20 mg/kg of 11 and ICV injection of 0.2 ng of IL1β. The 1 h interval between treatment with the inhibitors and IL1β ICV injection was chosen based on the brain PK analysis presented above. All animals were sacrificed at 3 h after compound or vehicle treatment and 2 h after ICV injection of IL1β. Brain EVs were purified as previously described.52

Size distribution and concentration of brain EVs were analyzed using the TRPS method. There were no significant differences in EV size distribution between experimental groups (Figure 6a). As previously reported,52 the collected fraction (F2) consists mostly of small exosome-size EVs with a mode equal to 80 ± 5 nm based on TRPS analysis. A high abundance of exosome-sized EVs was confirmed by TEM analysis (Figure 6c). As expected we found that ICV injection of IL1β significantly increased the concentration of small EVs (size 50–150 nm) purified from the brain, more than 2 times that of the control (Figure 6b). Dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors 11 suppressed IL1β-induced exosomal release to the control level (Figure 6b), while the less brain-permeable dual inhibitor 8 did not induce the same level of suppression.

Figure 6.

Dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitor 11 diminished IL1β-induced brain EV release in the rapid in vivo assay. Tau P301S (line PS19) mice were treated with compound 8 or 11 subcutaneously (SQ) at 20 mg/kg 1 h before IL1β injection (unilateral ICV injection of 0.2 ng). Two hours after IL1β injection, brain tissue was collected and used for brain EV isolation. a) Size distribution and concentrations of the brain EV samples were analyzed by Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS). b) Average concentrations of 50–150 nm size EVs from each treatment condition were compared. c) A representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the brain EV fraction is shown. d) Representative images of Western blot (WB) analysis of EV fractions from individual animals are shown; membranes were probed against exosomal markers (CD63 and syntenin-1), tau protein, and cell-type specific markers (astrocytic glutamate-aspartate transporter GLAST1, microglia marker CD11b, and neuronal isoform of Bridging Integrator 1, BIN1). e) Densitometry analysis of the WB images is shown. Histograms represent average relative signal intensity per each treatment group (mean ± SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni and Holm multiple comparison tests: #–P < 0.05 and ##–P < 0.01 compared to the control group, treated with vehicles for SQ and ICV injections, *–P < 0.05 and **–P < 0.01 compared to the IL1β group.

Biochemical analysis of brain-derived EVs (Figures 6d and 6e) confirmed that pretreatment with lead compound 11 led to a significant reduction of exosomal marker CD63 in exosome-enriched F2 fractions compared to the group treated only with IL1β. In contrast to significant changes in common exosomal marker CD63, levels of syntenin-1, a marker of a specific exosomal subpopulation generated through the Syndecan-Syntenin-ALIX pathway,53 were not different between the groups (Figures 6d and 6e). These results confirm that IL1β stimulation and nSMase2 inhibition have effects on specific populations of exosomes.

Our data suggest that the nSMase2-dependent pathway of exosome biogenesis is involved in tau-bearing exosome production in PS19 mice. Tau levels in the F2 fraction showed a strong trend of being elevated in animals treated with IL1β, with the average tau level being around 6 times higher in the IL1β-treated group compared to the control group (Figures 6d and 6e). Pretreatment with 11 significantly reduced IL1β-induced tau release by exosomes. The lead compound 8 was less effective in this study. The known variability of the tau load between PS19 mice likely accounts for the lack of statistical significance despite the high magnitude of tau changes.

Multiple brain cell types express IL1-R1, including subpopulations of neurons, astrocytes, choroid plexus cells, and ependymal cells;54 thus, the nSMase2-mediated exosomal release by different types of brain cells can be affected differently in response to acute increases in intracerebral IL1β concentration. We used a couple of cell-type specific markers to assess the origin of the IL1β/nSMase2 sensitive exosomal population. We found that levels of astrocytic glutamate-aspartate transporter 1 (GLAST-1) and microglial marker CD11b were significantly elevated in F2 fractions isolated from IL1β-treated animals. GLAST-1 is known to be sensitive to papain, the enzyme we used for gentle brain tissue dissociation. Therefore, we used a 30 kDa fragment of GLAST-1 instead of full-length protein for the analysis.55 Pretreatment with the dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitor 11 significantly reduced the level of astrocyte-derived exosomes and showed the same trend for microglia-derived exosomes, but the difference in CD11b levels between IL1β and 11/IL1β groups was not significant (Figures 6d and 6e). This finding correlates with previously demonstrated IL1β-induced nSMase2-mediated production of astrocyte-derived exosomes in wild-type mice.34,35 Microglia play an important role in tau spread,15,55 and inhibition of microglial nSMase2-dependent exosome release suppresses tau propagation in mouse models.15 The low levels of microglia response in our rapid in vivo assay may be attributed to saturation of microglia responses in 5–6 month old PS19 mice. Microglia activation is already detectable in 3 month old PS19 mice and precedes astrogliosis.48

Recently, Bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1), a known genetic risk factor for AD, was connected to tau seed release through exosomes in human AD and male PS19 mice.56 We analyzed levels of BIN1 in our F2 samples. Neuronal BIN1 isoform 1, but not microglia specific isoform 2, was highly enriched in the F2 fractions (Figure 6d). As in the case of exosomal tau, we found a high magnitude increase in exosome-associated BIN1 upon IL1β stimulation that was lower in the compound 11 treated group, but no statistically significant changes were found due to the high variability of individual levels of BIN1 within each group (Figure 6d). This data suggests that nSMase2 and BIN1 could be a part of the same exosomal pathway responsible for tau release and spread in AD.

Overall, our rapid in vivo assay results demonstrate the effectiveness of novel dual AChE/nSMase2 inhibitor 11 in suppression of IL1β-induced release of tau-bearing exosomes in a tauopathy model.

Our discovery of a novel class of potent nSMase2/AChE dual inhibitors presents an opportunity for further evaluation and development of these agents as a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Our data supports the ability of the dual inhibitors to suppress tau propagation in vitro and release of tau carrying exosomes in vivo in an AD model. These dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitors would enhance cholinergic synaptic plasticity, reduce neuroinflammation,37 and most importantly suppress exosome-mediated tau propagation and tau uptake mediated through the M1/M3 muscarinic ACh receptors.38,57–59 This combination effect is unique, has not been evaluated previously in the disease, and clearly differentiates these agents from currently available AChE inhibitors for the treatment of AD. In concert, these mechanisms of action have the potential not only to address symptoms of AD by enhancing cholinergic activity but also to suppress cell-to-cell tau propagation (Figure 7), significantly altering an underlying cause of AD and thus be truly disease-modifying.

Figure 7.

A putative mechanism for dual nSMase2/AChE inhibition and suppression of EV/exosome-mediated propagation of tau pathology wherein nSMase2 inhibition suppresses exosome biogenesis while AChE inhibition reduces exosome uptake and improves cholinergic support.

METHODS

Compound Synthesis.

Unless stated otherwise, reactions were conducted in flame-dried glassware under an atmosphere of N2, and commercially obtained reagents were used as received. Sodium hydride, boron tribromide, boron trichloride, phenyl isocyanate, N,N’-disuccinimidyl carbonate (29), cyclohexyl isocyanate, 3,5-dimethylphenyl isocyanate, 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl isocyanate, 3-aminopyridine (33) , 4-aminopyridine (32), and 4-(trifluoromethyl)aniline (37) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Hydrazine (17), 4-methoxyphenyl isocyanate, 3-methoxyphenyl isocyanate, and N-ethylmethylamine (37) were obtained from Oakwood Products, Inc. 4-(Trifluoromethyl)-phenyl isocyanate and 3-amino-5-fluoropyridine (35) were obtained from Combi-Blocks. Methyl iodide was obtained from Alfa Aesar. Reaction temperatures were controlled using an IKAmag temperature modulator, and unless stated otherwise, reactions were performed at RT (approximately 23 °C). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted with EMD gel 60 F254 precoated plates (0.25 mm for analytical chromatography and 0.50 mm for preparative chromatography) and visualized using a combination of UV, anisaldehyde, iodine, and potassium permanganate staining techniques. Silicycle Siliaflash P60 (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm) was used for flash column chromatography. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker spectrometers (500 MHz) and are reported relative to residual solvent signals. Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ ppm), multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz), integration. Data for 13C NMR are reported in terms of chemical shift (125 MHz). 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker spectrometers (at 376 MHz) and reported in terms of chemical shifts (δ ppm). Data for IR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer UATR Two FT-IR spectrometer and are reported in terms of frequency absorption (cm-1). DART-MS spectra were collected on a Thermo Exactive Plus MSD (Thermo Scientific) equipped with an ID-CUBE ion source and a Vapur Interface (IonSense Inc.). Both the source and MSD were controlled by Excalibur software v. 3.0. The analyte was spotted onto OpenSpot sampling cards (IonSense Inc.) using volatile solvents (e.g., chloroform, dichloromethane). Ionization was accomplished using UHP He (Airgas Inc.) plasma with no additional ionization agents. The mass calibration was carried out using Pierce LTQ Velos ESI (+) and (−)ion calibration solutions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Optical rotations were measured with a Rudolph Autopol III Automatic Polarimeter. Any modification of the conditions shown in the representative procedures is specified in the corresponding schemes. The detailed methods for synthesis of the compounds are included in the Supporting Information.

Enzyme Activity and Kinetic Analysis Assay.

To evaluate nSMase2 inhibitory activity of tested compounds, cell lysates from HEK293T cells overexpressing human nSMase2 were used as the source of the nSMase2 enzyme.34 The enzyme activity was measured with or without inhibitor treatment using the Amplex Red Sphingomyelinase activity assay.42 For the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) assay we used human AChE (Sigma). The enzyme activity was measured with or without inhibitor treatment using the Amplex Red assay kit (Thermo Fisher A12217). The reaction was monitored for 60 min and read at 530/590 nm. The detailed methods for enzyme activity analysis are included in the Supporting Information.

Modeling of Compound Binding to nSMase2.

Molecular docking analysis of compounds was performed using the Swiss Dock server on our Area51 Work Area 51 R4 linux workstation. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to determine the binding free energy of compound 8 binding to nSMase2. An AMBER16 package was used to perform the MD simulation. The Antechamber module in AMBER was used to generate the parameters for compounds. The SwissDock web server was used to predict compound binding to nSMase2. The detailed methods for Western blotting analysis are included in the Supporting Information.

Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA).

To predict the potential for brain permeability, a Regis Technologies analytical column connected to an Agilent HPLC system was used. We used the IAM.PC.DD column for determination of the retention time of a compound to calculate the predicted CNS permeability. The detailed methods are included in the Supporting Information.

Human Serum Albumin (HSA) Binding Assay.

For HSA compound binding we used a CHIRAL column immobilized with HSA on an Agilent HPLC system. The detailed methods are included in the Supporting Information.

Preparation of Brain-Derived Synaptosomal Extracts.

Cryopreserved brain tissue obtained from the University of California Irvine was used for preparation of the synaptosomal fractions (P2 fractions, “P2”). The detailed methods are included in the Supporting Information.

Tau Propagation Assays.

We use the HEK293T Tau RD P301S FRET biosensor (tau biosensor) for evaluation of the inhibitors in functional tau propagation “D+R” (Donors plus Recipients) and EMT (EV-mediated transfer) assays. We have previously published the detailed protocols and validation of the assays using known nSMase2 inhibitors GW4869 and cambinol.14 The detailed methods for the assay are included in the Supporting Information.

Rapid in Vivo Assay and Brain EV Purification.

Using 5–6 month old male PS19 mice expressing human tau with the P301S mutation under control of the murine prion promoter, we performed intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of IL-1μ with or without pretreatment with dual nSMase2/AChE inhibitor followed isolation of EVs. The in vivo experiments were performed under an approved IACUC protocol. The detailed methods for the assay are included in the Supporting Information.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

For quality control purposes, small amounts of purified brain- or tissue culture-derived EVs were fixed on a copper mesh in glutaraldehyde/paraformaldehyde solution, stained with 2% uranyl acetate solution, and imaged on a JEOL 100CX electron microscope at 29,000× magnification.

Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing Analysis.

Size distribution and concentrations of EV samples were analyzed by the Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS) method using the qNano Gold instrument (Izon Science). NP100 nanopore (particle size range: 50–330 nm) and CPC100 calibration particles were used for the analysis. Data analysis was performed using qNano instrument software.

Immunoblot Analysis of EV Samples.

Electrophoresis of proteins was performed using 10–20% Tris-glycine gels in nonreducing (only for tetraspanins) or reducing (with addition of DTT) conditions; proteins were then transferred to the PVDF membrane and probed with primary antibodies (Supporting Table 2) followed by HRP conjugated secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescent signals were generated with the Super Signal West Femto substrate (Thermo Scientific Pierce 34095) and detected using a BioSpectrum 600 imaging system and quantified using VisionWorks Version 6.6A software (UVP; Upland, CA). The detailed methods for modeling analysis are included in the Supporting Information.

Statistical Analysis.

All data was expressed as the mean ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni and Holm multiple comparison method using an online web statistical calculator (http://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD). Only a subset of pairs relative to the DMSO group was simultaneously compared. Values of * or #<0.05 and ** or ##<0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the funding sources listed above that supported this work. We would like to thank W. W. Poon from UC Irvine for human autopsy brain samples, C. Rojas from John Hopkins School of Medicine for nSMase2-overexpressing HEK293 cells, and the UCLA Janis V. Giorgi flow cytometry and Brain Research Institute Electron microscopy core facilities.

Funding

The work was supported by Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at UCLA to V.J., National Institutes of Health (AG051386 to V.J.), and the National Science Foundation (DGE-1144087 for B.J.S. and CHE-1464898 for N.K.G.) These studies were supported by shared instrumentation grants from the NSF (CHE-1048804) and the National Center for Research Resources (S10RR025631).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschembio.0c00311.

Detailed experimental procedures, compound characterization data (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschembio.0c00311

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Tina Bilousova, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Bryan J. Simmons, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States

Rachel R. Knapp, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States

Chris J. Elias, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States

Jesus Campagna, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Mikhail Melnik, School of Nursing University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Sujyoti Chandra, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Samantha Focht, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Chunni Zhu, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Kanagasabai Vadivel, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Barbara Jagodzinska, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Whitaker Cohn, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Patricia Spilman, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Karen H. Gylys, School of Nursing University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States

Neil K. Garg, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Varghese John, Drug Discovery Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).El-Hayek YH, Wiley RE, Khoury CP, Daya RP, Ballard C, Evans AR, Karran M, Molinuevo JL, Norton M, and Atri A (2019) Tip of the Iceberg: Assessing the Global Socioeconomic Costs of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and Strategic Implications for Stakeholders. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 70 (2), 323–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, and Hyman BT (2011) Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med 1 (1), No. a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Masters CL, Bateman R, Blennow K, Rowe CC, Sperling RA , and Cummings JL (2015) Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis Primers 1 , 15056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Olivieri P, Lagarde J, Lehericy S, Valabrègue R, Michel A, Macé P, Caillé F, Gervais P, Bottlaender M, and Sarazin M (2019) Early alteration of the locus coeruleus in phenotypic variants of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol 6 (7), 1345–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Costandi M (2018) Ways to stop the spread of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 559 (7715), S16–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Selkoe DJ, and Hardy J (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med 8 (6), 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hardy J, and Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297 (5580), 353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, Castellani RJ, Crain BJ, Davies P, Del Tredici K, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Haroutunian V, Hof PR, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Iwatsubo T, Jellinger KA, Jicha GA, Kovari E, Kukull WA, Leverenz JB, Love S, Mackenzie IR, Mann DM, Masliah E, McKee AC, Montine TJ, Morris JC, Schneider JA, Sonnen JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Troncoso JC, Wisniewski T, Woltjer RL, and Beach TG (2012) Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J. Neuropathol Exp. Neurol 71 (5), 362–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, Mormino E, Chhatwal J, Amariglio R, Papp K, Marshall G, Albers M, Mauro S, Pepin L, Alverio J, Judge K, Philiossaint M, Shoup T, Yokell D, Dickerson B, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman B, Vasdev N, and Sperling R (2016) Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol 79 (1), 110–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD Sr., Navitsky M, Lu M, Salloway S, Schaerf FW, Jennings D, Arora AK, McGeehan A, Lim NC, Xiong H, Joshi AD, Siderowf A, Mintun MA, and Investigators FA-A (2017) Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain 140 (3), 748–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kametani F, and Hasegawa M (2018) Reconsideration of Amyloid Hypothesis and Tau Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci 12, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ishiki A, Okamura N, Furukawa K, Furumoto S, Harada R, Tomita N, Hiraoka K, Watanuki S, Ishikawa Y, Tago T, Funaki Y, Iwata R, Tashiro M, Yanai K, Kudo Y, and Arai H (2015) Longitudinal Assessment of Tau Pathology in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease Using [18F]THK-5117 Positron Emission Tomography. PLoS One 10 (10), No. e0140311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chiotis K, Saint-Aubert L, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, Leuzy A, Almkvist O, Savitcheva I, Jonasson M, Lubberink M, Wall A, Antoni G, and Nordberg A (2018) Longitudinal changes of tau PET imaging in relation to hypometabolism in prodromal and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Mol. Psychiatry 23 (7), 1666–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bilousova T, Elias C, Miyoshi E, Alam MP, Zhu C, Campagna J, Vadivel K, Jagodzinska B, Gylys KH, and John V (2018) Suppression of tau propagation using an inhibitor that targets the DK-switch of nSMase2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 499 (4), 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Asai H, Ikezu S, Tsunoda S, Medalla M, Luebke J, Haydar T, Wolozin B, Butovsky O, Kugler S, and Ikezu T (2015) Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci 18 (11), 1584–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dinkins MB, Dasgupta S, Wang G, Zhu G, and Bieberich E (2014) Exosome reduction in vivo is associated with lower amyloid plaque load in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 35 (8), 1792–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dinkins MB, Enasko J, Hernandez C, Wang G, Kong J, Helwa I, Liu Y, Terry AV Jr., and Bieberich E (2016) Neutral Sphingomyelinase-2 Deficiency Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Improves Cognition in the 5XFAD Mouse. J. Neurosci 36 (33), 8653–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wheeler D, Knapp E, Bandaru VV, Wang Y, Knorr D, Poirier C, Mattson MP, Geiger JD, and Haughey NJ (2009) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced neutral sphingomyelinase-2 modulates synaptic plasticity by controlling the membrane insertion of NMDA receptors. J. Neurochem 109 (5), 1237–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tabatadze N, Savonenko A, Song H, Bandaru VV, Chu M, and Haughey NJ (2010) Inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 perturbs brain sphingolipid balance and spatial memory in mice. J. Neurosci. Res 88 (13), 2940–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Tan LH, Tan AJ, Ng YY, Chua JJ, Chew WS, Muralidharan S, Torta F, Dutta B, Sze SK, Herr DR, and Ong WY (2018) Enriched Expression of Neutral Sphingomyelinase 2 in the Striatum is Essential for Regulation of Lipid Raft Content and Motor Coordination. Mol. Neurobiol 55 (7), 5741–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Stoffel W, Jenke B, Schmidt-Soltau I, Binczek E, Brodesser S, and Hammels I (2018) SMPD3 deficiency perturbs neuronal proteostasis and causes progressive cognitive impairment. Cell Death Dis 9 (5), 507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Babenko NA, and Shakhova EG (2014) Long-term food restriction prevents aging-associated sphingolipid turnover dysregulation in the brain. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr 58 (3), 420–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Filippov V, Song MA, Zhang K, Vinters HV, Tung S, Kirsch WM, Yang J, and Duerksen-Hughes PJ (2012) Increased ceramide in brains with Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 29 (3), 537–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bandaru VV, Troncoso J, Wheeler D, Pletnikova O, Wang J , Conant K, and Haughey NJ (2009) ApoE4 disrupts sterol and sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s but not normal brain. Neurobiol. Aging 30 (4), 591–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, and Simons M (2008) Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 319 (5867), 1244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Thery C (2011) Exosomes: secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol. Rep 3, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Guo BB, Bellingham SA, and Hill AF (2015) The neutral sphingomyelinase pathway regulates packaging of the prion protein into exosomes. J. Biol. Chem 290 (6), 3455–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Simon D, Garcia-Garcia E, Royo F, Falcon-Perez JM, and Avila J (2012) Proteostasis of tau. Tau overexpression results in its secretion via membrane vesicles. FEBS Lett. 586 (1), 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Polanco JC, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF, and Gotz J (2016) Extracellular vesicles isolated from brains of rTg4510 mice seed tau aggregation in a threshold-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem 291 (24), 12445–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wang Y, Balaji V, Kaniyappan S, Kruger L, Irsen S, Tepper K , Chandupatla R, Maetzler W, Schneider A, Mandelkow E, and Mandelkow EM (2017) The release and trans-synaptic transmission of Tau via exosomes. Mol. Neurodegener 12 (1), 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fiandaca MS, Kapogiannis D, Mapstone M, Boxer A, Eitan E, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Federoff HJ, Miller BL , and Goetzl EJ (2015) Identification of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease by a profile of pathogenic proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes: A case-control study. Alzheimer’s Dementia 11 (6), 600–7.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Abner EL, Jicha GA, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, and Goetzl EJ (2016) Plasma neuronal exosomal levels of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in normal aging. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol 3 (5), 399–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Saman S, Kim W, Raya M, Visnick Y, Miro S, Saman S, Jackson B, McKee AC, Alvarez VE, Lee NC, and Hall GF (2012) Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem 287 (6), 3842–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rojas C, Barnaeva E, Thomas AG, Hu X, Southall N, Marugan J, Chaudhuri AD,Yoo SW, Hin N, Stepanek O,Wu Y, Zimmermann SC, Gadiano AG, Tsukamoto T, Rais R, Haughey N, Ferrer M, and Slusher BS (2018) DPTIP, a newly identified potent brain penetrant neutral sphingomyelinase 2 inhibitor, regulates astrocyte-peripheral immune communication following brain inflammation. Sci Rep. 8 (1), 17715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rojas C, Sala M, Thomas AG, Datta Chaudhuri A, Yoo SW, Li Z, Dash RP, Rais R, Haughey NJ, Nencka R, and Slusher B (2019) A novel and potent brain penetrant inhibitor of extracellular vesicle release. Br. J. Pharmacol 176 (19), 3857–3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Mehta M, Adem A, and Sabbagh M (2012) New acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2012, 728983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Maurer SV, and Williams CL (2017) The Cholinergic System Modulates Memory and Hippocampal Plasticity via Its Interactions with Non-Neuronal Cells. Front. Immunol 8, 1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Morozova V, Cohen LS, Makki AE, Shur A, Pilar G, El Idrissi A, and Alonso AD (2019) Normal and Pathological Tau Uptake Mediated by M1/M3Muscarinic Receptors Promotes Opposite Neuronal Changes. Front. Cell. Neurosci 13, 403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Klein J (2007) Phenserine. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 16 (7), 1087–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Simmons BJ, Hoffmann M, Champagne PA, Picazo E, Yamakawa K, Morrill LA, Houk KN, and Garg NK (2017) Understanding and Interrupting the Fischer Azaindolization Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (42), 14833–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Tabrez S, and Damanhouri GA (2019) Computational and Kinetic Studies of Acetylcholine Esterase Inhibition by Phenserine. Curr. Pharm. Des 25 (18), 2108–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Santillo MF, and Liu Y (2015) A fluorescence assay for measuring acetylcholinesterase activity in rat blood and a human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y). J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 76, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Brandt RB, Laux JE, and Yates SW (1987) Calculation of inhibitor Ki and inhibitor type from the concentration of inhibitor for 50% inhibition for Michaelis-Menten enzymes. Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol 37 (3), 344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Airola MV, Shanbhogue P, Shamseddine AA, Guja KE, Senkal CE, Maini R, Bartke N, Wu BX, Obeid LM, Garcia-Diaz M, and Hannun YA (2017) Structure of human nSMase2 reveals an interdomain allosteric activation mechanism for ceramide generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114 (28), E5549–E5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Park SJ, Kim JM, Kim J, Hur J, Park S, Kim K, Shin H-J, and Chwae Y-J (2018) Molecular mechanisms of biogenesis of apoptotic exosome-like vesicles and their roles as damage-associated molecular patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115 (50), E11721–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Zhang X-J, and Greenberg DS (2012) Acetylcholinesterase involvement in apoptosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci 5, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Nalivaeva NN, Rybakina EG, Pivanovich I, Kozinets IA, Shanin SN, and Bartfai T (2000) Activation of neutral sphingomyelinase by IL-1beta requires the type 1 interleukin 1 receptor. Cytokine 12 (3), 229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TC, Maeda J, Suhara T, Trojanowski JQ, and Lee VM (2007) Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53 (3), 337–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kitazawa M, Cheng D, Tsukamoto MR, Koike MA, Wes PD, Vasilevko V, Cribbs DH, and LaFerla FM (2011) Blocking IL-1 signaling rescues cognition, attenuates tau pathology, and restores neuronal beta-catenin pathway function in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J. Immunol 187 (12), 6539–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Ghosh S, Wu MD, Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, LaFerla FM, Olschowka JA, and O’Banion MK (2013) Sustained interleukin-1beta overexpression exacerbates tau pathology despite reduced amyloid burden in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. J. Neurosci 33 (11), 5053–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Dickens AM, Tovar-Y-Romo LB, Yoo S-W, Trout AL, Bae M, Kanmogne M, Megra B, Williams DW, Witwer KW, Gacias M, Tabatadze N, Cole RN, Casaccia P, Berman JW, Anthony DC, and Haughey NJ (2017) Astrocyte-shed extracellular vesicles regulate the peripheral leukocyte response to inflammatory brain lesions. Sci. Signaling 10 (473), No. eaai7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Vella LJ, Scicluna BJ, Cheng L, Bawden EG, Masters CL, Ang CS, Willamson N, McLean C, Barnham KJ, and Hill AF (2017) A rigorous method to enrich for exosomes from brain tissue. J. Extracell. Vesicles 6 (1), 1348885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E, Melchior A, Degeest G, Geeraerts A, Ivarsson Y, Depoortere F, Coomans C, Vermeiren E, Zimmermann P, and David G (2012) Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat. Cell Biol 14 (7), 677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu X, Nemeth DP, McKim DB, Zhu L, DiSabato DJ, Berdysz O, Gorantla G, Oliver B, Witcher KG, Wang Y, Negray CE, Vegesna RS, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP, Robson MJ, Blakely RD, Popovich PG, Bilbo SD, and Quan N (2019) Cell-Type-Specific Interleukin 1 Receptor 1 Signaling in the Brain Regulates Distinct Neuroimmune Activities. Immunity 50 (2), 317–333.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Maphis N, Xu G, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Jiang S, Cardona A, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT, and Bhaskar K (2015) Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain 138 (6), 1738–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Crotti A, Sait HR, McAvoy KM, Estrada K, Ergun A, Szak S, Marsh G, Jandreski L, Peterson M, Reynolds TL, Dalkilic-Liddle I, Cameron A, Cahir-McFarland E, and Ransohoff RM (2019) BIN1 favors the spreading of Tau via extracellular vesicles. Sci. Rep 9 (1), 9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Gomez-Ramos A, Diaz-Hernandez M, Rubio A, Diaz-Hernandez JI, Miras-Portugal MT, and Avila J (2009) Characteristics and consequences of muscarinic receptor activation by tau protein. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 19 (10), 708–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Uwada J, Yoshiki H, Masuoka T, Nishio M, and Muramatsu I (2014) Intracellular localization of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor through clathrin-dependent constitutive internalization is mediated by a C-terminal tryptophan-based motif. J. Cell Sci 127 (14), 3131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Perez M, Avila J, and Hernandez F (2019) Propagation of Tau via Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Neurosci 13, 698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.