Abstract

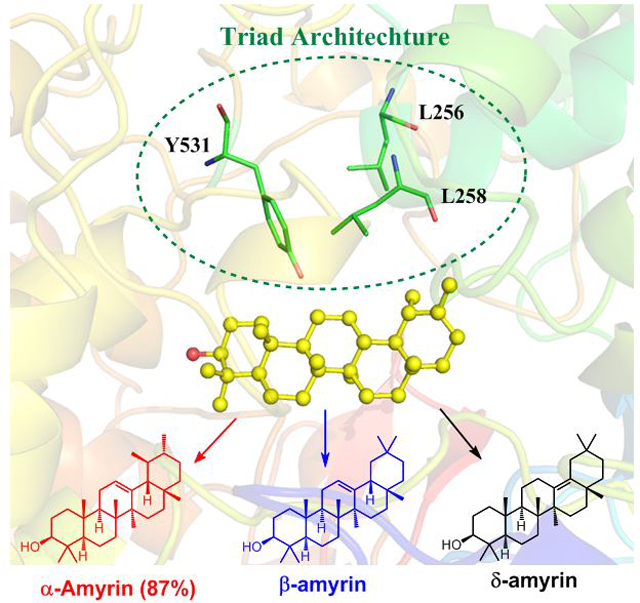

Ordered polycyclization catalyzed by oxidosqualene synthases (OSCs) morph a common linear precursor into structurally complex and diverse triterpene scaffolds with varied bioactivities. We identified three OSCs from Iris tectorum. ItOSC2 is a rare multifunctional α-amyrin synthase. Sequence comparisons, site-directed mutagenesis and multiscale simulations revealed that three spatially clustered residues, Y531/L256/L258 form an unusual Y-LL triad at the active site, replacing the highly conserved W-xY triad occurring in other amyrin synthases. The discovery of this unprecedented active site architecture in ItOSC2 underscores the plasticity of terpene cyclase catalytic mechanisms and opens new avenues for protein engineering towards custom designed OSCs.

Keywords: Oxidosqualene Cyclase, Enzyme Catalysis, Enzyme Promiscuity, QM/MM, Triterpene

Graphical Abstract

The active site chamber of the α-amyrin synthase of Iris tectorum features an unusual triad of spatially clustered residues. This triad is crucial in determining the 4th and 5th ring architecture and the chemical diversity of products generated from pluripotent common intermediates at the late stages of a highly complex and ordered catalytic cascade.

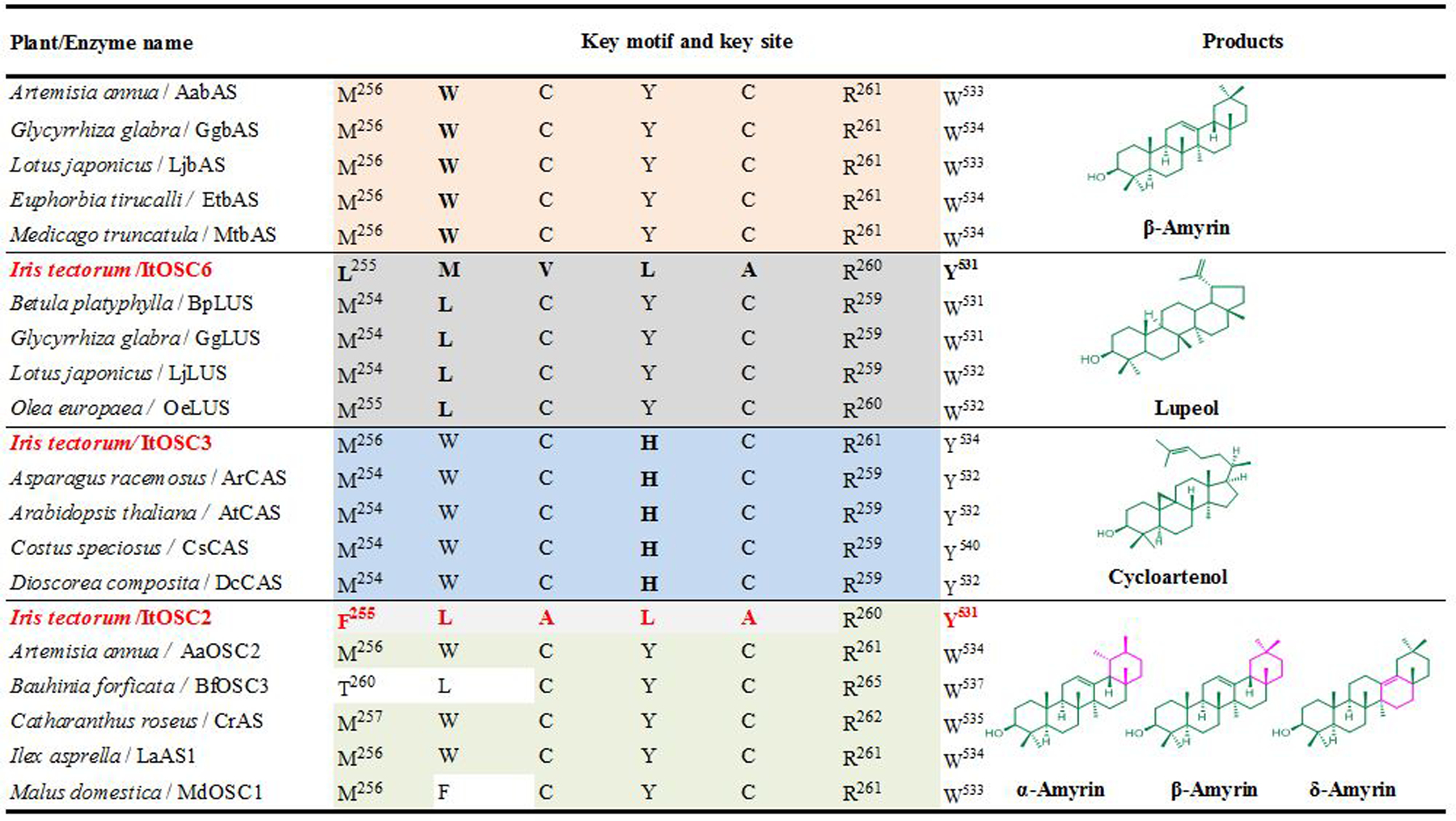

Triterpenoids are abundant in nature and have numerous pharmaceutical, agricultural and industrial biotechnology applications.1–6 2,3-Oxidosqualene cyclases (OSCs) are the gatekeepers towards triterpenoid diversity in plants,7 with more than 125 OSCs functionally characterized.8 Divergent evolution of OSCs led to substantial sequence diversity and functional plasticity.9 β-amyrin is the common intermediate of oleananes, one of the most prevalent pentacyclic triterpene scaffolds in plants. The catalytic mechanisms of β-amyrin synthases have been investigated,10 revealing a highly conserved MWCYCR motif at the catalytic center in most (Fig. 1). Lupeol synthases producing related pentacyclic triterpenols display an almost identical conserved MLCYCR motif. A W259L mutation in the MWCYCR motif of the β-amyrin synthase of Panax ginseng is sufficient to reprogram this enzyme to yield lupeol as the major product (lupeol:β-amyrin = 2:1).11 Correspondingly, a L256W replacement in the MLCYCR motif of the lupeol synthase of Olea europea led to the production of β-amyrin with only traces of the native product lupeol. However, additional polymorphism in this motif, together with the plasticity of the preceding 2~3 amino acids12–14 also contribute to OSC functional diversity and pentacyclic triterpenoid structural diversity. Thus, further mechanistic insights into the relationship between OSC sequences and the corresponding products are still necessary.

Figure 1.

Conserved active site motifs and major products of representative plant OSCs.11, 14

Herein, we identified three OSCs that are expressed predominantly in the leaves and flowers of the roof iris (Iris tectorum), in keeping with the distribution of triterpenols in this plant (Supplementary Information Figs. S1–S3). The cDNAs for these enzymes were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae SE-1015 and the produced triterpenols were identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). ItOSC3 produced cycloartenol (Fig S4), while ItOSC6 yielded lupeol exclusively (SI Figs. S5, S19–20 and S33–38, Table S7). In contrast, ItOSC2 afforded α-amyrin (87% of total triterpenoids), together with β-amyrin and δ-amyrin as the minor products (Fig. 1, SI Figs. S6, S15–18 and S21–32, Table S5–6). α-Amyrin is the precursor of the ursane pentacyclic triterpenes that display potent anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic and anti-obesity activities.16–20 Unlike β-amyrin synthases, OSCs producing α-amyrin predominantly (>80%) are rare in nature13 (Fig. 1).

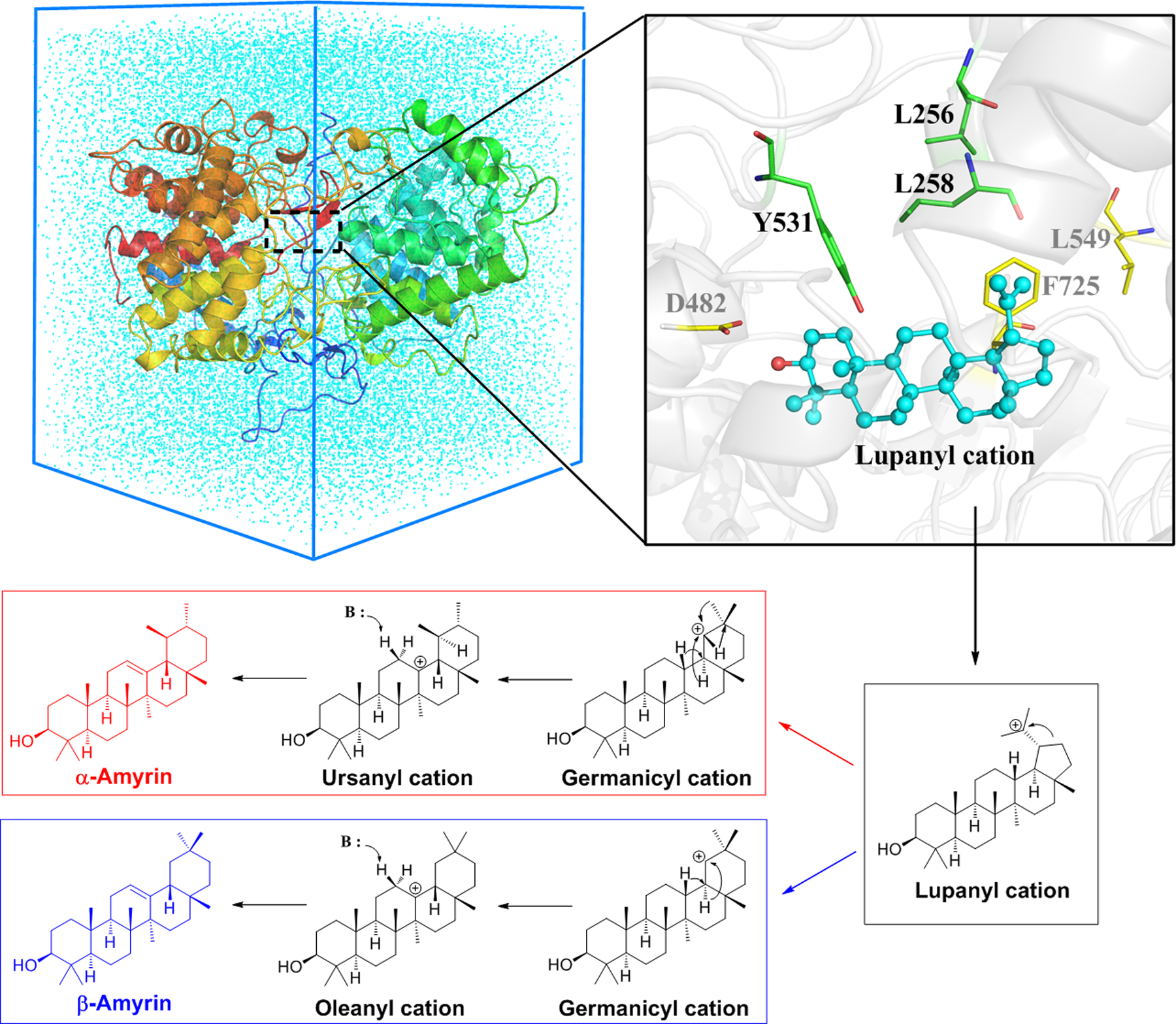

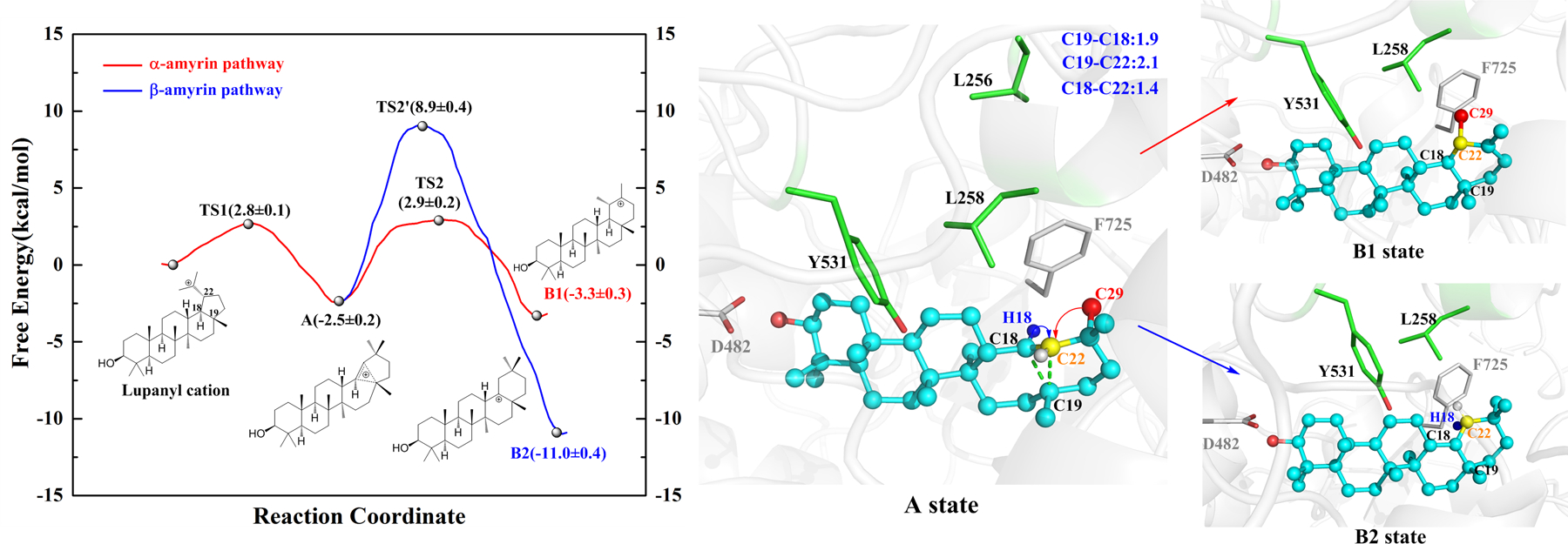

While ItOSC3 contains the expected cycloartenol synthase active site motif M256WCHCR261, surprisingly both ItOSC2 and ItOSC6 lack this anticipated motif. Instead, ItOSC2 displays an unexpected F255LALAR260 motif, while ItOSC6 contains a similarly non-canonical L255MVLAR260 motif (Fig. 1, SI Figs. S7–S9). We used quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics-molecular dynamics (QM/MM-MD) simulations in conjunction with the replacement of key amino acids to investigate the contribution of these novel active site architectures to OSC catalysis. Concentrating on the late stages of the catalytic cascade (Fig. 2), E ring expansion of the lupanyl cation yields the germanicyl cation with the 6-6-6-6-6 ring system that is shared by all ItOSC2 products. Next, a 1,2 hydride shift (H13 to C18) initiates the β-amyrin pathway while methyl transfer (Me29 to C19) instigates the α-amyrin pathway. Considering the free energy profile during ItOSC2 catalysis (Fig. 3), ring expansion of the lupanyl cation conquers a 2.8 kcal/mol barrier to yield the secondary germanicyl cation (A state) with a metastable secondary carbocation in a non-classical bridged ring. This is similar to the intermediate validated in the 1,6-closure pathway of Nicotiana tabacum 5-epi-aristolochene synthase.21 In the A state, the positive charge of the germanicyl cation (C19+) is stabilized by an intramolecular cation–π (C18=C22) interaction (Fig. 3). 1,2 methyl transfer (Me29 from C20 to C19) leads to the taraxasteryl cation (B1 state) in the α-amyrin pathway, with a small reaction barrier (2.9 kcal/mol) and negligible heat release (~0.8 kcal/mol). The β-amyrin pathway is also feasible via an 1,2 hydride shift in the A state (H18 from C18 to C19), because of the notable exothermicity of the reaction (~8.5 kcal/mol, B2 state). The higher reaction barrier (8.9 kcal/mol) is due to the requisite additional conformational change of the germanicyl intermediate to allow for the 1,2 hydride shift, while the A state is well configured for the 1,2 methyl transfer. Thus, the α-amyrin pathway is favored because of its high kinetic feasibility, while the β-amyrin pathway is plausible due to thermodynamic superiority. The relative energy profiles for the additional reactions from B1 to α-amyrin, and those from B2 to β-amyrin and δ-amyrin are shown in SI Fig. S11.

Figure 2.

QM/MM-MD model of ItOSC2 and the distinct reaction pathways from the common lupanyl cation to α-amyrin (red) and β-amyrin (blue). The pathway affording the lupanyl cation is shown in SI Fig. S10. The QM area of L256, L258, Y531 and the lupanyl cation was described by the M06–2X functional with the 6–31G* basis set. See the Supporting Information for computational details.

Figure 3.

Free energy profiles of the branching pathways towards α-amyrin (red) and β-amyrin (blue), catalyzed by ItOSC2. Representative models for the A and the B1 and B2 states are shown based on QM/MM-MD modelling. Energy profiles for the subsequent reactions leading to the final products appear in SI Fig. S11.

Based on our QM/MM-MD models of ItOSC2, residues F255, A257 and A259 in the FLALAR motif are sterically distant from the lupanyl cation, while L256 and L258 are close to this intermediate (SI Fig. S12). An additional residue, Y531 also appears near the intermediate. Y531 equivalents are conserved in OSCs with intermediates in the chair-boat-chair conformation (CBC, the geometry of the first three fused rings). Since ItOSC2 acts on a chair-chair-chair (CCC) substrate, the presence of Y531 proximal to the substrate was unexpected.

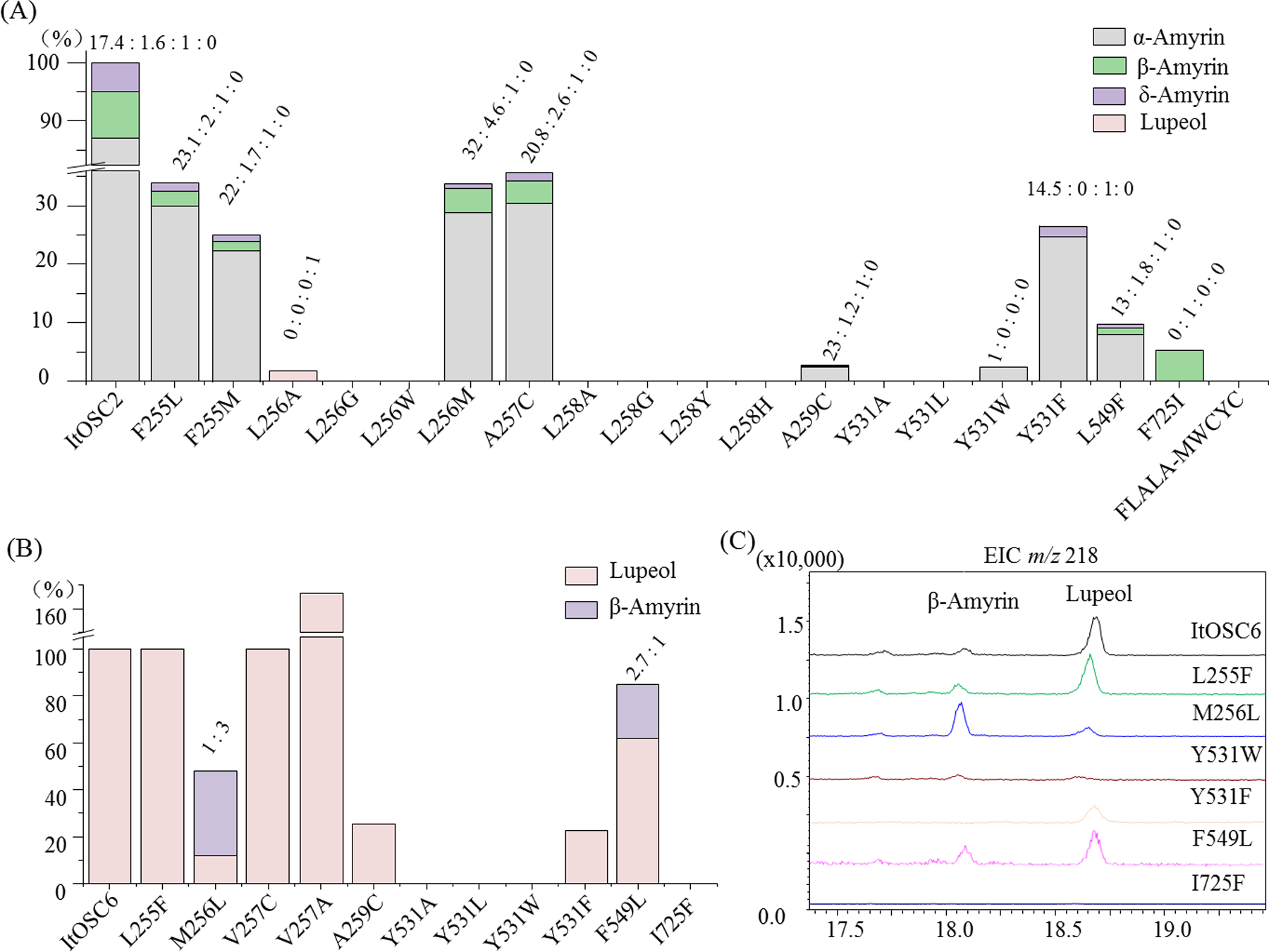

To substantiate the modeling, we conducted site-directed mutagenesis in ItOSC2 (Fig. 4A). No triterpenols were produced upon replacement of the entire F255LALA259 motif with the MWCYC motif characteristic of β-amyrin synthases. As computationally predicted, mutating second shell residues such as F255 (to L or M) or A257 (to C) reduced productivity but did not alter product distribution. In contrast, the aliphatic amino acids proximal to the substrate at positions 256 and 258 were essential for maintaining α-amyrin synthase activity (Fig. 4A). Thus, amyrin biosynthesis in ItOSC2 was found to be highly sensitive to the steric bulk of the residues occupying these positions, since the L256A mutant afforded only barely detectable amounts of lupeol, while the L256G, L256W, L258A, L258G, L258Y, and L258H mutants were all devoid of activity. In contrast, the relatively conservative L256M mutation led to no change in the product spectrum, although productivity was reduced (Fig. 4A). We propose that L258 and L256 do not directly interact with the carbocation intermediate. Instead, they provide a hydrophobic surface that impedes premature deprotonation. In addition, while W257 in β-amyrin synthases tightly binds Me29 of the germanicyl cation by CH-π interactions,10, 22 the corresponding L256 residue in ItOSC2 should allow 1,2 transfer of Me29 to C19 en route to α-amyrin.

Figure 4.

Product profiles of S. cerevisiae SE-10 expressing various OSCs. Relative productivity and product distribution for (A), ItOSC2; and (B), ItOSC6 variants. (C), Extracted ion GC-MS chromatograms of ItOSC6 mutants.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the unusual Y531 residue of ItOSC2 was also informative. Neither small (Y531A) noraliphatic (Y531L) amino acids could sustain productivity at this position, while increased bulk (Y531W) was highly detrimental (Fig. 4A). We propose that Y531 is involved in the proper orientation of the lupanyl cation and other late stage intermediates. Since the active site cavity is accessible to solvent at Y531 (Fig. 5A), the hydroxyl group of this residue may also participate in a hydrogen bond network with water molecules and facilitate deprotonation23 of the intermediate at C12 or C13, leading to the regioisomeric amyrin products. Fittingly, absence of the hydroxyl group (Y531F) reduces productivity (29.2%), but this mutant enzyme continues to yield α-amyrin as the dominant product, with a minor amount of δ-amyrin also obtained (Fig. 4A). δ-Amyrin may form as a shunt product from premature deprotonation at the B2 state (SI Fig. S11).

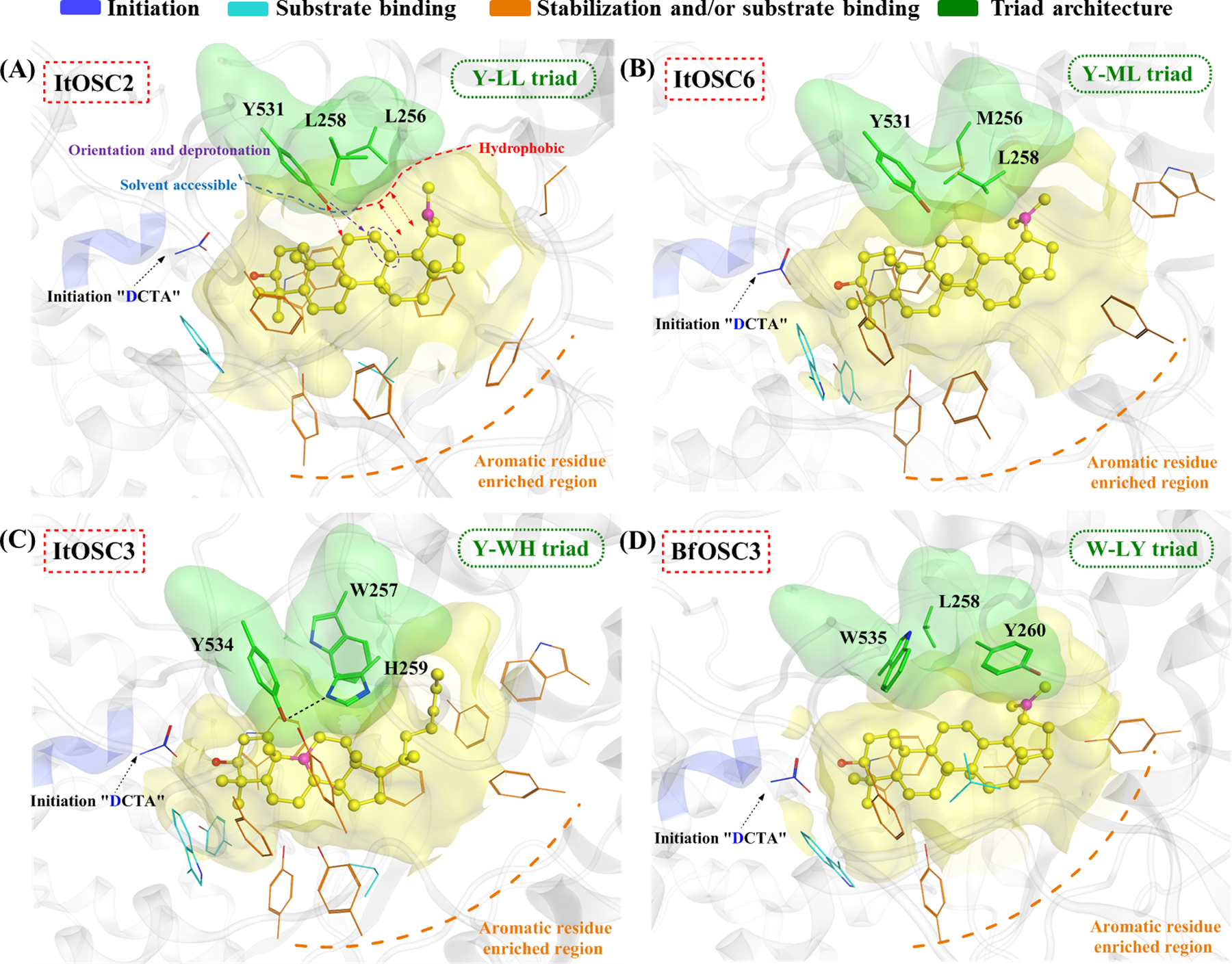

Figure 5.

Active site cavity comparisons among (A), ItOSC2; (B), ItOSC6; (C), ItOSC3; and (D), BfOSC3. The conserved triad and their surface are rendered in green. Intermediates (lupanyl cation for ItOSC2, ItOSC6 and BfOSC3, and protosteryl C9 cation for ItOSC3) and cavity shape are shown in yellow, with the positively charged carbon in magenta. Additional residues are colored as indicated. Red dashed arrows represent steric effects, while a purple dashed arrow indicates the proposed involvement of Y531 in the orientation and (together with the solvent) the deprotonation of the carbocation.

To further contrast the novel Y-LL triad of ItOSC2, we compared the QM/MM-MD model of this enzyme with those of additional OSCs. The active site of the lupeol synthase ItOSC6 features a Y-ML triad. This is part of an LM256VL258AR motif that contacts the intermediate from the ceiling of the active site cavity (Fig. 5B). Conservative mutations in the second shell of the cavity still allowed lupeol synthesis, and reduced (A259C), did not affect (V257C), or even increased productivity (V257A). However, the M256L mutation in the active site triad refashions ItOSC6 into a multifunctional β-amyrin synthase, with lupeol as the minor product (lupeol:β-amyrin=1:3, Fig. 4B). Just as with ItOSC2, the Y531A, Y531L and Y531W mutations eliminated triterpenol production, emphasizing the importance of the steric bulk of this triad residue. Same as with ItOSC2, the Y531F mutation decreased productivity but did not change the product spectrum, indicating the importance of the hydroxyl group for product turnover. Additional comparisons of the QM/MM-MD models of ItOSC2 and ItOSC6 highlighted another two distinguishing residues (F549 and I725 in ItOSC6 vs. L549 and F725 in ItOSC2) that contact the opposite face of the lupanyl cation. The I725F mutant of ItOSC6 is inactive, while the F549L mutant is a promiscuous enzyme producing lupeol and β-amyrin efficiently (2.7:1, Fig. 4B). In ItOSC2, the complementary F725I and L549F mutations both strongly diminish productivity. However, while the L549F mutant continues to produce α-amyrin, the only detectable product for the F725I mutant is β-amyrin (Fig. 4A). Thus, cation-π interactions10 are important to channel the reactive intermediate towards the appropriate regioisomer. Taken together, the three residues at the ceiling of the catalytic cavity (positions 256, 258 and 531, ItOSC2 numbering), and the two residues at the floor of the chamber (549 and 725, ItOSC2 numbering) are all critical for product yield and/or specificity.

The cycloartenol synthase ItOSC3 features a Y534-WH259 triad (Fig. 5C). Y534 is typical for OSCs that process intermediates with CBC conformation, yielding lanosterol, cycloartenol and similar tetracyclic 6-6-6-5 products (SI Fig. S8 and Table S1).22, 24 Y534 participates in a hydrogen bond with the conserved H259 (Fig. 5C), and abstracts the C8–β H from the tetracyclic protosteryl cation before transfer to H259 that serves as the final proton acceptor.23 Although the equivalent Y531 appears as part of the Y531-LL258 triad in ItOSC2, it is not oriented and constrained by nearby residues. The conformational flexibility of Y531 may accommodate ligands with the CCC conformation, and support a different deprotonation regioselectivity to afford α-, β- or δ-amyrin as the products.

Just like EtAS of Euphorbia tirucalli,10 the classic β-amyrin-producing OSC GgbAS from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) features a W534-W257Y259 triad (SI Fig. S13). Y259 stabilizes the baccharenyl secondary cation during D-ring formation using cation-π interactions, while W257 stabilizes and orients the germanicyl cation by tightly binding its Me29 moiety using CH–π interactions.10–11, 22 This may channel the ligand towards β- or δ-amyrin by favoring the H18 to C19 hydride shift. In contrast, multifunctional OSCs producing α-amyrin as the main product feature a more variable W-xY triad (x=W, F, L or M; SI Tables S1 and S2). One such enzyme, BfOSC3 of the Brazilian orchid tree (Bauhinia forficata)13 contains a leucine at the variable position of the triad (Fig. 5D). This residue, just as L256 in ItOSC2, should allow the facile 1,2 shift of the Me29 moiety to C19. Considering that the triad of the multifunctional α-amyrin synthases is variable and that the spectra of their minor products are also different,13, 25–26 we speculate that Nature has evolved divergent structural solutions for the active site architectures of these enzymes. In addition, idiosyncratic differences in the second shell residues may also lead to subtle modifications in the contour and charge distribution of the active site cavity, leading to different product spectra.

In summary, heterologous expression, site-directed mutagenesis and QM/MM-MD simulations revealed three spatially adjacent residues that form an unexpected Y-LL triad at the ceiling of the catalytic cavity of the multifunctional α-amyrin synthase ItOSC2 from Iris tectorum. Comparisons with OSCs producing α-amyrin, β-amyrin, lupeol and cycloartenol correlated the observed sequence polymorphism at this triad with the yield and product spectrum of these enzymes, and further clarified how pentacyclic 6-6-6-6-6(5) triterpenoid chemical diversity is generated from pluripotent common intermediates at the late stages of the highly complex and ordered catalytic cascade. Importantly, identical main products may be afforded by OSCs with different triad sequences, indicating the parallel evolution of orthogonal structural solutions in Nature for the same catalytic task. These findings will guide combinatorial mutagenesis of the triad and its second shell residues to evolve designer OSCs that afford known or novel ursane, oleanane or other triterpenoids for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical or cosmetic applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Work in the authors’ laboratories was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81874333 to L.D., and No.21773313 to R.W.); the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (No.2018-1002-SF-0437 to L.D.); the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (2016A030306038 to R.W.); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFE0191500 to S.W); the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch project ARZT-1361640-H12-224 to I.M.); the Higher Education Institutional Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities in Hungary (NKFIH-1150-6/2019 to I.M.); and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIGMS 5R01GM114418 to I.M).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. Details of the cloning and yeast transformations, alignment and evaluation of amino acid sequences for ItOSCs. Materials, methods and computational details, GC-MS and NMR analysis, QM/MM-MD simulations.

I.M. has disclosed financial interests in Teva Pharmaceutical Works Ltd. (Hungary), and the University of Debrecen (Hungary) which are unrelated to the subject of the research presented here. All the other authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Thimmappa R; Geisler K; Louveau T; O’Maille P; Osbourn A Triterpene Biosynthesis in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol 2014, 65, 225–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Augustin JM; Kuzina V; Andersen SB; Bak S Molecular Activities, Biosynthesis and Evolution of Triterpenoid Saponins. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 435–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Osbourn A; Goss RJ; Field RA The Saponins: Polar Isoprenoids with Important and Diverse Biological Activities. Nat. Prod. Rep 2011, 28, 1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Faizal A; Geelen D Saponins and their Role in Biological Processes in Plants. Phytochem. Rev 2013, 12, 877–893. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sun W; Xue H; Liu H; Lv B; Yu Y; Wang Y; Huang M; Li C Controlling Chemo- and Regioselectivity of a Plant P450 in Yeast Cell toward Rare Licorice Triterpenoid Biosynthesis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 4253–4260. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Li J; Yang J; Mu S; Shang N; Liu C; Zhu Y; Cai Y; Liu P; Lin J; Liu W; Sun Y; Ma Y Efficient O-Glycosylation of Triterpenes Enabled by Protein Engineering of Plant Glycosyltransferase UGT74AC1. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3629–3639. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Karunanithi PS; Zerbe P Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in the Evolution of Plant Terpenoid Chemical Diversity. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10,1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Goossens A; Osbourn A; Michoux F; Bak S Triterpene Messages from the EU-FP7 Project TriForC. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Xue ZY; Duan LX; Liu D; Guo J; Ge S; Dicks J; OMaille P; Osbourn A; Qi XQ Divergent Evolution of Oxidosqualene Cyclases in Plants. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 1022–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hoshino T beta-Amyrin Biosynthesis: Catalytic Mechanism and Substrate Recognition. Org. Biomol. Chem 2017, 15, 2869–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kushiro T; Shibuya M; Masuda K; Ebizuka Y, Mutational Studies on Triterpene Synthases: Engineering Lupeol Synthase into β-Amyrin Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 6816–6824. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kushiro T; Shibuya M; Ebizuka Y Chimeric Triterpene Synthase. A Possible Model for Multifunctional Triterpene Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Srisawat P; Fukushima E; Yasumoto S; Robertlee J; Suzuki H; Seki H; Muranaka T Identification of Oxidosqualene Cyclases from the Medicinal Legume Tree Bauhinia Forficata : a Step toward Discovering Preponderant α-Amyrin-producing Activity. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 352–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lodeiro S; Xiong QB; Wilson WK; Kolesnikova MD; Onak CS; Matsuda SPT An Oxidosqualene Cyclase Makes Numerous Products by Diverse Mechanisms: A Challenge to Prevailing Concepts of Triterpene Biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 11213–11222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang CX; Su XY; Sun MC; Zhang MT; Wu JJ; Xing JM; Wang Y; Xue JP; Liu X; Sun W; Chen SL Efficient Production of Glycyrrhetinic Acid in Metabolically Engineered Saccharomyces Cerevisiae via an Integrated Strategy. Microb Cell Fact. 2019, 18. 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zhang N; Liu S; Shi S; Chen Y; Xu F; Wei X; Xu Y Solubilization and Delivery of Ursolic-acid for Modulating Tumor Microenvironment and Regulatory T Cell Activities in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Control. Release 2020, 320, 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Liu F; Wang YN; Li Y; Ma SG; Qu J; Liu YB; Niu CS; Tang ZH; Li YH; Li L; Yu SS Minor Nortriterpenoids from the Twigs and Leaves of Rhododendron latoucheae. J. Nat. Prod 2018, 81, 1721–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Honda T; Rounds BV; Bore L; Finlay HJ; Favaloro FG Jr.; Suh N; Wang Y; Sporn MB; Gribble GW Synthetic Oleanane and Ursane Triterpenoids with Modified Rings A and C: a Series of Highly Active Inhibitors of Nitric Oxide Production in Mouse Macrophages. J. Med. Chem 2000, 43, 4233–4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Rollinger JM; Kratschmar DV; Schuster D; Pfisterer PH; Gumy C; Aubry EM; Brandstotter S; Stuppner H; Wolber G; Odermatt A 11beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase 1 Inhibiting Constituents from Eriobotrya japonica Revealed by Bioactivity-guided Isolation and Computational Approaches. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2010, 18, 1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chu X; He X; Shi Z; Li C; Guo F; Li S; Li Y; Na L; Sun C Ursolic Acid Increases Energy Expenditure through Enhancing Free Fatty Acid Uptake and beta-Oxidation via an UCP3/AMPK-dependent Pathway in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2015, 59, 1491–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang F; Wang YH; Tang X; Wu R Catalytic Promiscuity of the non-Native FPP Substrate in the TEAS Enzyme: non-Negligible Flexibility of the Carbocation Intermediate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2018, 20, 15061–15073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ito R; Nakada C; Hoshino T beta-Amyrin Synthase from Euphorbia tirucalli L. Functional Analyses of the Highly Conserved Aromatic Residues Phe413, Tyr259 and Trp257 Disclose the Importance of the Appropriate Steric Bulk, and Cation-pi and CH-pi Interactions for the Efficient Catalytic Action of the Polyolefin Cyclization Cascade. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 15, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Diao H; Chen N; Wang K; Zhang F; Wang Y-H; Wu R Biosynthetic Mechanism of Lanosterol: A Completed Story. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2157–2168. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Thoma R; Schulz-Gasch T; D’Arcy B; Benz J; Aebi J; Dehmlow H; Hennig M; Stihle M; Ruf A Insight into Steroid Scaffold Formation from the Structure of Human Oxidosqualene Cyclase. Nature 2004, 432, 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Moses T; Pollier J; Shen Q; Soetaert S; Reed J; Erffelinck ML; Van Nieuwerburgh FC; Vanden Bossche R; Osbourn A; Thevelein JM; Deforce D; Tang K; Goossens A OSC2 and CYP716A14v2 Catalyze the Biosynthesis of Triterpenoids for the Cuticle of Aerial Organs of Artemisia annua. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 286–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Andre CM; Legay S; Deleruelle A; Nieuwenhuizen N; Punter M; Brendolise C; Cooney JM; Lateur M; Hausman JF; Larondelle Y; Laing WA Multifunctional Oxidosqualene Cyclases and Cytochrome P450 Involved in the Biosynthesis of Apple Fruit Triterpenic Acids. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1279–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.