Abstract

Objectives:

The primary purpose of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators of Fuel Up to Play 60 (FUTP60) program implementation.

Methods:

This was an observational study occurring over 20 months in 4 schools in metropolitan Denver, Colorado. Key informant interviews and FUTP60 surveys examined the barriers and facilitators of program implementation and utilization of other health-promotion programs.

Results:

Program advisors stated that the adaptability of FUTP60 eased program implementation in schools, helped schools to meet wellness policy goals, and that the program message resonated with students.

Conclusions:

FUTP60’s adaptability to a school’s needs, its simple messaging and student-centric model were major facilitators of program implementation and should be considered when implementing other school-based programs.

Keywords: health behavior, school-based program, physical activity, nutrition

Childhood obesity is a significant public health problem. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 16.9% of children and adolescents in the United States (US) between the ages of 2 and 19 years old are obese.1 Colorado ranks 23rd for childhood obesity2 with approximately 22.9% of Colorado children ages 1-14 years categorized as overweight or obese.2 These high rates of overweight and obesity among children cause concern due to the fact that obesity increases the risk for developing a multitude of diseases, including children’s asthma, coronary heart disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes, and cancer.3–6

Many efforts are underway to improve nutrition and promote physical activity to reduce childhood obesity rates. Increasing physical activity7–11 and promoting healthier diets12–14 are associated with lower rates of obesity, better mental health, and improved academic performance. Unfortunately, few interventions have been successful in achieving sustained changes in physical activity and diet.

Because of the large proportion of time children spend in school, many health-promoting interventions have taken place in schools. School-based interventions have exhibited only modest success in reducing obesity;15,16 however, some promising aspects of interventions include: (1) encouraging school breakfast participation;17 (2) limiting the availability of unhealthy foods in schools;18–21 and (3) integrating physical activity into school curriculum22,23 or classroom breaks.9,24,25 The large number of health-promoting programs in schools causes concern that programs will deplete school resources, be overlapping or competitive, and confuse students and teachers. The 2 school districts we studied offered over 30 health-promoting programs in their elementary and middle schools. Despite the large number of programs offered, few programs include evaluation of program effectiveness and limited information exists for identifying which programs are most likely to succeed and how programs may overlap with one another.

Fuel Up to Play 60 (FUTP60) is a school-based program. Co-developed by the National Dairy Council (NDC) and the National Football League (NFL), in collaboration with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), FUTP60 attempts to improve school wellness by promoting the consumption of food groups to encourage (FGTE) – fruits, vegetables, whole grains and low-fat/fat-free dairy, 60 minutes of physical activity daily, and supporting environmental changes in schools to improve nutrition and physical activity opportunities. As of spring 2012, approximately 73,000 schools across the US had enrolled in FUTP60, with 26,000 adult program advisors and 11 million students involved.26 FUTP60 utilizes a student-centric model that encourages students to help lead, participate in, and personally commit to healthy eating and physical activity opportunities at schools. FUTP60 participants report that high levels of student and staff involvement have resulted in additional administrative support for other wellness initiatives.26 This finding, along with FUTP60’s simple, direct messaging about healthy eating, physical activity, and student involvement, suggests that FUTP60 may be a useful platform for the adoption and implementation of other health-promoting programs in schools.

The primary purpose of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators of program implementation with the goals of: (1) informing successful implementation of FUTP60; and (2) informing successful implementation of other school-based health-promoting programs.

METHODS

This was an observational study occurring over 20 months in 4 schools within 2 school districts in the metropolitan area of Denver, Colorado (US). We selected 2 school districts representing distinctly different populations, based on their percentage eligibility for federally-subsidized free and reduced meals and ethnic diversity, to evaluate differences and similarities in barriers and facilitators of program implementation across socioeconomic settings. Schools were selected based on enrollment size, the age range of students, prior inexperience implementing FUTP60, and willingness to implement FUTP60 and to participate in the evaluation component of the project. Students and staff present in participating schools during fall 2011 through spring 2013 were exposed to FUTP60.

Data were collected from 2 elementary and 2 middle schools during the 2011-2012 and 2012-2013 school years. Participating districts/schools were: one elementary (ages 6 through 11) and one middle school (ages 12 through 15) from District 1 and one elementary and one K-8 school (ages 5 through 14) from District 2. District 1 is a low-income, ethnically diverse school district; District 2 is a middle/high-income and more ethnically homogenous school district. Demographic data were provided by each school district and are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

School Demographic Data from the 2011-2012 School Year

| Students Enrolled (N) | Native American (%) | White (%) | Black (%) | Asian (%) | Hispanic (%) | Native Hawaiian (%) | Two or More (%) | FRLa (%) | ESLb (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District 1 | ||||||||||

| School A (Elementary) | 559 | 0.4 | 11.4 | 14.3 | 3.0 | 65.1 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 88.4 | 53.0 |

| School B (Middle) | 686 | 0.9 | 6.6 | 21.9 | 2.2 | 65.6 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 86.2 | 42.7 |

| District 2 | ||||||||||

| School C (Elementary) | 707 | 0.9 | 69.4 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 8.77 | 5.53 |

| School D (K-8) | 534 | 0.2 | 52.1 | 7.1 | 21.2 | 12.4 | 0.4 | 6.6 | 3.71 | 0.93 |

Note.

FRL=Percent of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch

ESL=Percent of English Second Language students

Fuel Up to Play 60

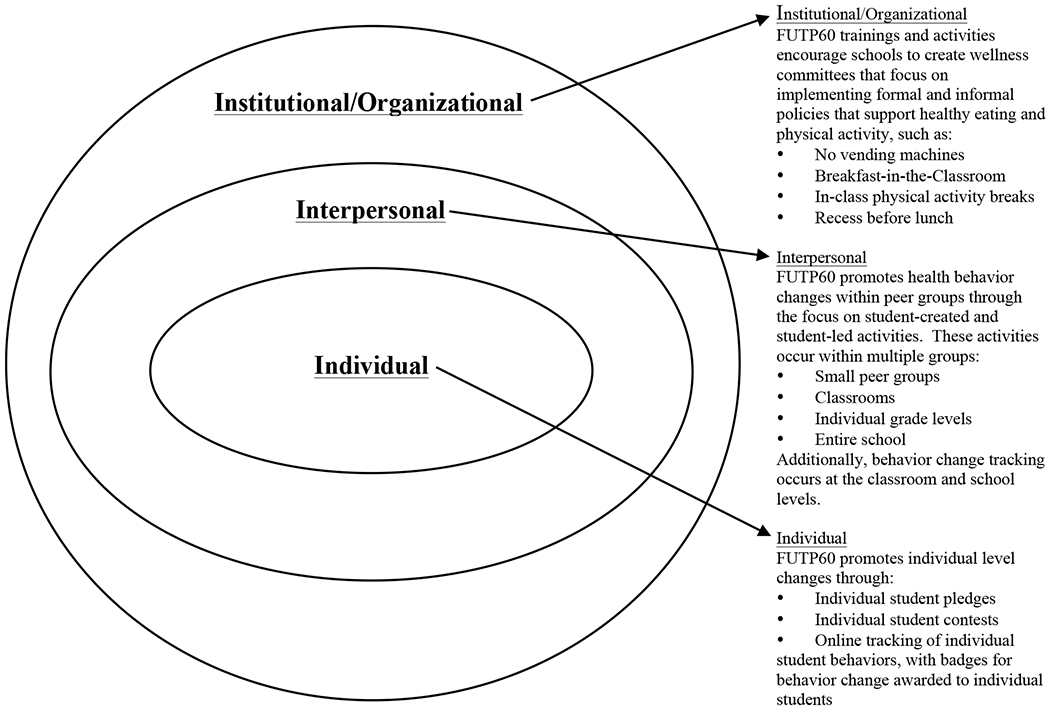

FUTP60 program design was informed by evidence from previous studies indicating that the school environment, including a healthy school food environment17–20 and classroom level physical activity,9,22–25 contributes to healthy student behaviors, ultimately leading to improved health status.15,16,27 FUTP60 utilizes a flexible, customizable approach to allow schools to establish changes that are feasible within their current social and political environments. FUTP60 implementation was established in the context of the social-ecological model of behavior change by focusing on multiple levels of influence.28 Specifically, FUTP60 focuses on the first 3 levels of influence identified by the social-ecological model: (1) Individual; (2) Interpersonal; and (3) Institutional/Organizational. Figure 1 specifies the methods through which FUTP60 addresses health behavior change in each of these levels of influence.

Figure 1.

Using the Social-Ecological Model in the FUTP60 Program to Promote Health Behavior Change at the Individual, Interpersonal, and Institutional/Organizational Levels

FUTP60 implementation was led by one or more adult program advisors and the student-led FUTP60 team. Typically, school personnel and/or parents volunteered to serve as FUTP60 program advisors due to their interest in healthy living. However, in some schools, principals selected program advisors due to lack of volunteerism or the political environment of the school. Depending on the program advisor’s desired approach student team members were selected by program advisors, applied to be team members, or volunteered to participate. Prior to program implementation the program advisors and 2 student team members attended a one-day FUTP60 implementation training provided by the regional dairy council. This represents the typical manner in which FUTP60 is implemented in schools throughout the US. Researchers requested that the schools implement FUTP60 in the typical manner to represent the true effects of the program in a normal school setting, as well as to increase the generalizability of study findings. Researchers made every effort to avoid indirectly affecting program implementation through data collection efforts.

FUTP60 implementation includes 6 steps, which are shown in Table 2. The program advisors provide support to the student-led team by working with school personnel to implement FUTP60 activities and guiding students regarding which Plays (action strategies) are feasible based on school- and district-level policies. The program advisors can also apply for up to $4000 in grant funds to support program implementation, including a small stipend for the advisor. The student-led team is responsible for selecting Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Plays and for implementing the Plays.

Table 2.

Six Steps of Fuel Up to Play 60 Implementation

|

Step 1: Join the League • Select Program Advisor (s)- Teachers, staff or parents can sign up to be a Program Advisor • Students are encouraged to join FUTP60 by creating a profile on the FUTP60 website and pledging to eat healthy and be physically active for at least 60 minutes a day. • Display FUTP60 signage in a prominent place within the school |

|

Step 2: Build Team and Draft Key Players Build the FUTP60 school team by enlisting students, staff and parents. |

|

Step 3: Kickoff • Implement a school-wide event to introduce FUTP60 at the school. • Introduce the year’s Campaigns • Give students and staff information about how healthy eating and physical activity can help students learn better and create a school-wide sense of the positive effects that are possible with FUTP60. |

|

Step 4: Survey the Field • Students complete the School Wellness Investigation (SWI), which is designed to help students leant about the current nutrition and physical activity environment in their school and to identify opportunities to improve the school. • The SWI can be used as a “before” and “after” measure of the school’s progress. |

|

Step 5: Game Time •Students select one of five Healthy Eating or five Physical Activity Plays in the current Playbook. • Students implement the selected play at the school to promote long-term changes in their school. • Each Play has tools and resources to generate ideas for other activities/plays students can do on their own. • Students can also participate through the website dashboard by logging their food and activity and participating in activities to earn badges. |

|

Step 6: Light Up the Scoreboard • Students can submit their school’s success story by sharing pictures and stories on the website. • Students can log on to their dashboard and share their participation in badge-earning activities. • Students can earn FUTP60 rewards for sharing their stories. |

Program enrollment data on the FUTP60 website and FUTP60 surveys (School Wellness Investigation,29 Program Utilization Survey) provided participation numbers, Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Play selections, and information regarding implementation of other health-promotion programs already occurring in schools.

Key informant interviews were conducted with program advisors and co-advisors in each school and were based on 10 standard questions, with the use of exploratory follow-up questions. Program advisors and, in some cases principals, were interviewed in a group setting, with questions posed to the entire group, including time for open discussion and follow-up questions for greater depth and clarity. The interviews focused on the ease and degree of FUTP60 implementation, barriers and facilitators of program implementation, student perceptions of FUTP60, and the manner in which FUTP60 was utilized in the school (as a stand-alone program, in conjunction with other programs, etc).

Interview results were compiled and compared for themes and commonalities. We applied the RE-AIM framework, which assesses 5 dimensions for evaluation of public health interventions,30 to interpret our data. Reach included the number of students who enrolled in the program through the FUTP60 website and the number of students who actively participated in activities and other health-promotion programs at the school (students were not required to enroll on the FUTP60 website to participate in program activities). Efficacy was determined by program advisors’ perception of efficacy. Adoption was identified using interviews and FUTP60 surveys. Implementation was determined based on how many of the 6 FUTP60 program implementation steps (Table 2) the school completed, as well as the number of Plays the school implemented. Maintenance was informed by the number of program activities and other program components that were sustained over the 2-year study period, as well as by continued advisor and student commitment to participating in FUTP60.

RESULTS

An overview of the results from FUTP60 program surveys (School Wellness Investigation and Program Utilization Survey) and FUTP60 website activity are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

FUTP60 Program Implementation Activities: 2011-2013

| Activity | 2011-2012 School Year | 2012-2013 School Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School A (District 1 Elementary School) | Kick-Off Event | YES | NO |

| Student-Led Team | YES | NO | |

| FUTP60 Grant | YES | NO | |

| Healthy Eating Plays | • Taste Test a Rainbow • Family Night Taste Tests • Student-designed play |

• Family Night Taste Tests | |

| Physical Activity Plays | • Culture Dance Club • After School Skills and Drills • After School Fun Fitness Activities |

• None | |

| Student Web Enrollment | 40 (7.16%) | 17 (3.15%) | |

| School B (District 1 Middle School) | Kick-Off Event | YES | NO |

| Student-Led Team | YES | NO | |

| FUTP60 Grant | YES | YES | |

| Healthy Eating Plays | • Breakfast Taste Tests • Menu Makeover • Point of Purchase Promotions • Student-led play |

• School Lunch Taste Tests • Breakfast in the Classroom Pilot |

|

| Physical Activity Plays | • In-class Physical Activity Breaks • Hoops for Heart • Student-led play |

• Hoops for Heart | |

| Student Web Enrollment | 327 (47.7%) | 328 (47.7%) | |

| School C (District 2 Elementary School) | Kick-Off Event | YES | NO |

| Student-Led Team | YES | NO | |

| FUTP60 Grant | YES | YES | |

| Healthy Eating Plays | • Breakfast Taste Tests • A Little Paint Can Go a Long Way • Taste Test a Rainbow • Taste Test Days • Student-led: Cougar Club Garden • Student-led: Cougar Club Garden |

• Breakfast Taste Tests • Taste Test a Rainbow • Grow a Pizza Garden • Build Your Own Shakeup |

|

| Physical Activity Plays | • School-wide Walk-It Club • In-class Physical Activity Breaks • Student-led: Before-school recess • Student-led: Kidlympics • Student-led: Unified Games |

• School-wide Walk-It Club • In-class Physical Activity Breaks • Get Into Intramurals • Student-led: Pre-school lap run • Student-led: Unified Games • Student-led play |

|

| Student Web Enrollment | 377 (53.3%) | 386 (52.7%) | |

| School D (District 2 K-8 School) | Kick-Off Event | YES | YES |

| Student-Led Team | YES | YES | |

| FUTP60 Grant | YES | YES | |

| Healthy Eating Plays | • Build Your Own Shakeup • Student-led play |

• Breakfast Taste Tests • Build Your Own Shakeup • Oatmeal Challenge |

|

| Physical Activity Plays | • In-class Physical Activity Breaks • Student-led: Before-school gym time • Student-led play |

• Student-led: Basketball tournament | |

| Student Web Enrollment | 179 (35.0%) | 270 (52.6%) | |

FUTP60 Program Reach

In school A, 8% of students (N = 40) enrolled in FUTP60 for year 1 and 3% (N = 17) enrolled for year 2. During year 1, 20%-39% of students participated in various FUTP60 activities. During year 2, 226 students and family members attended Family Night Taste Tests.

In school B, 48% of students (N = 327) enrolled in FUTP60 during both years 1 and 2, and 20%-39% of students participated in FUTP60 activities throughout both school years. Participation in other health-promoting programs included 52% of students (N = 340) participating in a physical activity program in year 1 and 31% (N = 200) participating in year 2. Advisors reported that Fitness Breaks were “widely” utilized in classes during year 1, and 7 classrooms (33% or approximately 220 students) piloted Breakfast in the Classroom (BIC) during year 2.

In school C, 53% of students (N = 377) enrolled in FUTP60 for years 1 and 2. Overall, 100% of students (N = 705) participated in school-wide FUTP60 activities during both years. Participation in other health-promoting programs included 38% of students (N = 266) participating in Kidlympics, before-school recess, the school garden and the Unified Games. Several school-wide traditions (described under Program Adoption) were established during year 1 that continued into year 2, and FUTP60 was the school’s yearbook theme during year 1.

In school D, 35% of students (N = 179) enrolled in FUTP60 for year 1 and 53% (N = 270) enrolled for year 2. Additionally, 60%-79% of students participated in FUTP60 activities in year 1 and 80%-89% participated in activities in year 2. Participation in other health-promoting programs included 5% of students (N = 30) attending Open Gym before school, and participation in school breakfast increased from 12 students per day to approximately 40-50 students per day.

FUTP60 Program Efficacy

School A bought physical activity equipment with FUTP60 funds. Program advisors identified taste tests as important for increasing awareness of the quality and value of school meals, and they stated that FUTP60 “effectively reached wellness goals.”

School B program advisors reported that FUTP60 helped to “partially reach the wellness goal” of a 72% increase in breakfast consumption during the statewide testing weeks. Program advisors also stated that “students understood the concepts of FUTP60.”

School C program advisors reported that “Students understood the concept and related it to other programs.” This school built traditions through the use of FUTP60 Plays, including Eat a Rainbow Day and Before School Recess. Parent involvement was high due to school encouragement of parent participation through multiple programs. Program advisors reported that “key outcomes are being achieved.” These key outcomes included increased participation in physical activity before school and during recess, as well as children’s increased acceptance of new fruits and vegetables through the Eat a Rainbow Day (which was repeated multiple times throughout the year).

School D program advisors stated that FUTP60 grant funds motivated and empowered students to develop and implement their ideas. The FUTP60 Healthy-Eating Play ‘Build Your Own Shakeup’ increased breakfast and lunch participation. The student-created play “Open Gym + Flat Fourteeners” was attended by older students who previously did not participate in similar school programs. Program advisors reported that FUTP60 was “effective at reaching wellness goals.”

FUTP60 Program Adoption

School A program advisors reported that students “loved the program.” The PE teacher used FUTP60 banners and messaging to support other health-promoting programs. Nutrition Services and students participated in planning and delivery of “Taste Testing” to parents at Family Health Night. School staff perceived this as increasing awareness of the nutritional quality and palatability of cafeteria food, which aligned with school goals. Barriers to adoption included staff shortages and reassignments. Program advisors reported high student interest in before- and after-school physical activity programming but lack of staff capacity to implement said programming.

School B was slow to start the program due to confusion regarding the student-led team; however, inclusion of the cafeteria manager and a second organizing meeting accelerated program adoption. The cafeteria manager created promotions using FUTP60 funds, modified the presentation of FGTE in the lunch line, conducted breakfast taste tests, promoted breakfast during statewide testing, added smoothies to the menu using the blender purchased with FUTP60 funds, and promoted chef demonstrations of healthy food preparation methods. In year 2, a BIC pilot was delivered in 7 classrooms (33%). Program advisors offered Hoops for Heart (an American Heart Association program) during study hall hour and, based on student feedback, provided additional sport choices (volleyball, soccer) to increase participation. Program advisors used FUTP60 as a platform to support other health-promoting programs, such as Girls on the Run, Culinary Boot Camp, and Hoops for Heart, to increase the reach, adoption, and participation in activities. Obstacles to adoption included limited gym space to accommodate additional activities and lack of gym availability after school. Changes in their workload and scheduling requirements prevented advisors from supporting a student-led team during the 2012-2013 school year.

According to School C program advisors FUTP60 became part of the school culture as it “was easily understood and made sense to kids and teachers.” Students designed the “Kidlympics” to allow inclusion of younger students in the physical activity games. “Unified Games,” a physical activity tradition established by School C that partnered able-bodied and physically challenged students in sport competitions, was promoted through FUTP60 both years. FUTP60 was utilized as a platform to promote the school’s goals. Parents invented a physical activity event called the “Miles mile” which became another school tradition. FUTP60 provided a “brand” for eating healthy and being active that aligned with this school’s goals.

In School D, the cafeteria manager supported FUTP60 strategies to increase healthy eating behaviors and utilized FUTP60 funds to purchase a blender for making smoothies. The cafeteria manager worked with Nutrition Services to include smoothies as a reimbursable meal through the School Breakfast Program and started serving breakfast early in order to meet student demand to participate in both the smoothie program and Open Gym. In year 2 program advisors limited the student team to 5th-8th graders and required students to apply for a leadership team position to produce high quality student leaders who were interested in promoting FUTP60 program goals. Obstacles to program adoption included the required registration and confusion regarding which Healthy Eating Plays aligned with district-level nutrition requirements.

FUTP Program Implementation

In year 1, School A completed 5 of the 6 FUTP60 steps and implemented 5 Plays. In year 2, the program advisors were assigned additional duties and only one FUTP60 step, implementation of one Healthy Eating Play, was partially completed.

In year 1, School B completed 5 of the 6 FUTP60 steps and implemented 6 Plays. In year 2, School B completed 2 of the 6 FUTP60 steps and implemented 3 Plays.

In year 1, School C completed 5 of the 6 FUTP60 steps and implemented 6 Plays. FUTP60 was adapted for implementation in the classroom and in school-wide initiatives with broad organizational support and reinforcement. In year 2, 2 of the 6 FUTP60 steps were completed and 9 Plays were implemented. Implementation through school-wide initiatives continued throughout year 2.

In year one, School D completed 5 of the 6 FUTP60 steps and implemented 4 Plays. In year 2, all 6 FUTP60 steps were completed and 5 Plays were implemented. In year 2 the FUTP60 team organized and implemented a school-wide basketball tournament attended by “the entire school.”

FUTP60 Program Maintenance

In School A, FUTP60 banners were used continuously because they reinforced physical activity and taste testing was maintained because it aligned with school- and district-level goals. However, insufficient staffing was the primary barrier to maintaining full program implementation. Advisors recommended shortening the FUTP60 implementation timeline (October through March) to coordinate with school timelines and advisor availability.

In School B, barriers to FUTP60 maintenance included significant changes in staff duties and a new school principal in year 2 who did not support BIC and who made substantial changes to the school schedule and priorities. Factors supporting FUTP60 maintenance were the alignment of Nutrition Services goals with the FUTP60 goal to increase sales of FGTE, institutional support for Hoops for Heart and other physical activity programs, student interest and involvement in the program, and program advisors who were responsive to student needs and interests.

In School C, barriers to maintenance included staff reassignment and the change in delivery format. Factors that supported sustainability included the institutionalization of FUTP60 through new school traditions. Health-promoting programs – Go Slow Whoa, playground makeover, Focus on Fun (recess program), and the Watch DOG Program (Dads Of Great students) were reinforced by FUTP60 concepts, thereby strengthening program maintenance.

In School D, facilitators of program maintenance included shared program and school goals, the program advisor’s ability to work effectively with parents, and student leadership of FUTP60 implementation. Program advisors reported that: “When kids have an opportunity to take their ideas and make them happen it is a really powerful experience for them and the school.” Program advisors identified conflicting school commitments, such as year-end testing, as barriers to program implementation and maintenance. Similar to School A, School D program advisors recommended that the program implementation timeline should be shortened to reduce stress and conflicts with other school, staff, and student commitments.

DISCUSSION

FUTP60 was partially implemented and sustained in every school during this 2-year project. All 4 schools delivered 5 of the 6 components of FUTP60, indicating that the program was relatively easy and accessible for schools to implement. Whereas initial implementation of the program was successful, there were several challenges to program maintenance during year 2. Program advisors identified several barriers and facilitators of program implementation and maintenance.

Several of the barriers were due to functional challenges at the program and school levels. One such barrier was the recommended FUTP60 program implementation timeline. Ideally, FUTP60 implementation begins when school starts and continues through the end of the school year. However, 2 of the 4 schools indicated that competing demands, such of end-of-year testing, made it difficult to adhere to the program implementation timeline. Advisors suggested shortening the implementation timeline by one month at the beginning and end of the school year to prevent overlapping program activities with school priorities. Another functional limitation identified by low-income schools was the lack of computer access, which prevented students from using the FUTP60 website for student enrollment and behavior tracking. These advisors overcame this barrier through the use of paper enrollment and tracking tools provided by FUTP60. Infrastructure limitations, such as limited gym availability, reduced the ability to implement Physical Activity Plays. The use of in-class “Fitness Breaks” overcame this limitation. Each of these barriers represents challenges many schools face when implementing programs. Adjusting program implementation timelines and providing alternative solutions to address lack of computer access and infrastructure challenges could improve schools’ ability to implement programs, including FUTP60.

Another set of barriers involved school personnel capacity, including changes in workload, changes in school staffing, and a lack of knowledge regarding district-level Nutrition Services policies. Workload changes inhibited program advisors’ ability to maintain program implementation. Advisors in Schools A and B experienced significant changes in their workload and duties within their schools. School A stated that the loss of several staff members at the beginning of the school year, along with a concomitant increase in workload, resulted in an “unhappy school atmosphere.” These changes limited FUTP60 implementation during year 2. Despite the challenges School A experienced, the advisors developed a plan that would allow them to implement FUTP60 during the subsequent school year by using parent volunteers. Advisors were motivated to maintain the program because of students’ desire to participate in FUTP60 activities they experienced during year 1, such as before- and after-school physical activity programming and a student-led jump-rope routine. The students’ and advisors’ desires to continue participating in FUTP60 demonstrated the significant value of the program. School B also experienced a personnel change with the hiring of a new principal. The new principal was unsupportive of BIC, which impeded their ability to implement school-wide changes. Other school-based health-promoting programs, such as the CATCH31 and Planet Health32 programs, have identified the need for buy-in from school administrators and teachers to achieve successful program implementation.33 This highlights the need for programs to proactively elicit the support and buy-in of all school personnel, and principals in particular, to facilitate successful program implementation.

In addition to workload and staffing changes, program advisors’ lack of knowledge regarding district-level Nutrition Services policies created challenges in selecting Healthy Eating Plays they could feasibly implement. The involvement of Nutrition Services personnel in program decision-making and implementation enabled program advisors to overcome this barrier and to achieve larger and more sustainable changes through the coordination of efforts with those of School Nutrition Services. FUTP60 specifically advises schools to include personnel from School Nutrition Services as part of their FUTP60 team because “the expertise and guidance of School Nutrition Professionals is vital to help engage and empower students to ‘fuel up’ with the nutrient-rich foods they often lack.”34 This study underscores the importance of actively involving School Nutrition Services personnel, who are experts in school food regulations, in planning and implementing school-based health-promoting programs focused on healthy eating. FUTP60’s active promotion of involving School Nutrition Services personnel in program planning and implementation represents a major strength of the FUTP60 program.

Whereas program advisors identified several barriers to program implementation and maintenance, they also recognized several aspects of FUTP60 that facilitated program implementation in their schools. One of the most important facilitators for enhancing success was program adaptability and alignment with school goals, which has been identified as crucial to the success of other school-based programs, including CATCH,31 Planet Health32 and Not-on-Tobacco.33,35 Additional facilitators of program success included recruiting an interested and available program advisor, FUTP60-provided funding support, students’ understanding of program messaging, and the student-centric nature of the program. The adaptability of FUTP60 allowed schools to implement FUTP60 in a manner that supported their school’s needs and goals and to use FUTP60 messaging to support other health-promoting programs. For example, in School B the FUTP60 student team used FUTP60 to promote Hoops for Heart because it was a venue for achieving 60 minutes of physical activity daily and aligned with both FUTP60 and PE teacher goals. The ability of schools to use FUTP60 as an umbrella program is a major strength because it enables schools to leverage activities that are already successful and ingrained in the school’s culture, while gaining the benefit of FUTP60’s funding opportunities and simple, kid-friendly messaging.

The flexible structure of FUTP60 also allows schools to implement the program, even in resource-scarce environments, by selecting activities that support their unique needs. For example, School A was able to implement one FUTP60 activity during year 2 – Taste Testing at Family Health Night – because it aligned with the school’s goal of demonstrating the improved quality of school food to parents. Despite significant workload and staffing changes during year 2, FUTP60’s adaptability allowed School A to successfully implement the program in a way that was meaningful to their school. Nutrition Services personnel were typically the strongest advocates for program adoption because FUTP60 goals aligned with their goals of promoting breakfast. Overall, our findings demonstrate the value of aligning program and school goals.33 Such alignment of goals meets schools’ unique needs and improves the level of program implementation and maintenance.

Selecting a program advisor who was interested and available to facilitate program implementation also played a crucial role in the success of FUTP60. School D’s program advisor implemented FUTP60 fully in both years by engaging parent volunteers, allowing students to participate in leadership roles and collaborating with nutrition services. The program advisor at School C found innovative ways to use FUTP60 in the classroom, established a supportive infrastructure and effectively utilized the student-led team. Other schools’ program advisors expressed belief in the quality of FUTP60 but were unable to implement the program fully due to workload, time constraints, and lack of school-wide support. These findings suggest that program advisors must not only be interested in the program but also must possess adequate time and support to promote program success. The need to provide staff support for implementing school-based programs was also identified following implementation of the CATCH,31 Planet Health32 and Not-on-Tobacco programs.33,35 Schools interested in implementing FUTP60 or other school-based programs should consider whether their staff possesses the necessary interest, time and support to implement a program successfully and should explore alternatives, such as parent volunteers, to lend support when needed.

The grant funds provided by FUTP60 were a major facilitator of program success. All of the program advisors identified the funds as valuable, and one advisor even stated that the funds were “the most important aspect” of the program. These funds were invaluable for several reasons. First, the funds provided a small stipend for the advisor. The provision of a stipend positively reinforced the amount of time advisors spent working on the program. Second, the funds allowed schools to purchase equipment to support FUTP60 implementation. Thirdly, the funds empowered students. School D’s program advisor stated that “When kids have an opportunity to take their ideas and make them happen, it is a really powerful experience for them.” FUTP60’s ability to provide funding is relatively unique and one of the program’s major strengths. Student empowerment is one of the most unique and compelling aspects of FUTP60. The program empowers students to make individual and health-promoting behavior and environmental changes with the support of funds, simple messages, tools and resources, and a student-led structure.

FUTP60’s simple, direct messaging about healthy eating and physical activity was cited consistently as being a major facilitator of program implementation. Advisors stated that “students understood the concepts of FUTP60” and it “made sense to kids and teachers.” This simple messaging allowed schools and students to “relate it [FUTP60] to other programs.” In School A students were able to link FUTP60 to a local campaign (Go Slow Whoa) because “the kids know that Go Slow Whoa is connected to FUTP60, even though it was not directly stated.” Finally, FUTP60’s simple messaging made it possible for students to lead program implementation.

The student-centric nature of FUTP60 is perhaps its greatest strength and was cited by every advisor as a facilitator of program implementation and maintenance. Importantly, the schools that engaged their student-led teams most effectively also showed the highest levels of program adoption, implementation and maintenance. Even in schools with lower levels of program implementation, students’ desire to continue the program kept it going. The Healthy Buddies program36 is another program that utilizes peer-based healthy-living lesson plans as a means to improve student health. Several studies have shown that the Healthy Buddies program is effective at improving healthy-living knowledge in both older and younger students,36–38 it attenuates increases in central adiposity37 and overall weight gain,38 reduces body mass index z-score and waist circumference,39 and it is effective in multiple-settings, including in Aboriginals from the Tsimshian Nation39 and the Oji-Cree First Nation,38 and in middle-income white children in British Columbia.36 Our findings, along with the successes of the Healthy Buddies program, suggest that student involvement and peer-led approaches have a positive impact on program adoption, implementation, and maintenance, as well as on healthy-living knowledge and behaviors. Additional research regarding the effectiveness of peer-led programming as a means to improve child health and behavior and as a means to implement school-based health promotion programs is warranted.

There were some limitations to this study. One was the limited number of schools. Despite the small number of schools, we intentionally selected socioeconomically diverse schools to improve the generalizability of our findings. The short-time period over which this study occurred limited our ability to determine long-term program maintenance. Additional longitudinal studies should be undertaken to determine factors affecting long-term program maintenance. Finally, we did not interact directly with students because we wanted to avoid indirectly affecting program implementation. This meant we were unable to understand students’ responses to the program first-hand. Whereas we attempted to gain said information through advisor interviews and surveys, additional research is warranted to understand individual student perceptions of the program and understanding of program messaging.

The schools we examined were able to implement FUTP60 due to the adaptability of the program and its alignment with school goals, a finding repeated elsewhere in the school-based program literature.33 Program advisors identified several barriers to program implementation, including the program implementation timeline, increased advisor workload, and lack of knowledge regarding district-level Nutrition Services policies. Facilitators of program implementation included program adaptability and alignment with school goals,33 students’ understanding of program messaging, and the student-centric nature of the program. It is particularly important that schools consider whether or not potential program advisors have the time and support33 necessary to implement a program. Schools also should coordinate efforts with other key personnel, such as Nutrition Services employees and should first consider whether a program aligns with school goals33 before attempting to implement FUTP60 or other programs. The adaptable nature of FUTP60 makes it a potential platform for implementing other school-based health-promoting programs. Program advisors agreed with the statement that “our school used FUTP60 as a platform to implement other programs,” and each school demonstrated FUTP60’s ability to serve as a platform for supporting implementation of other health-promoting programs. Future research regarding the use of FUTP60 as platform for other school-based health-promotion programs is warranted. The use of FUTP60 as a platform could reduce the workload required for implementing other programs, and could capitalize on FUTP60’s simple messaging and student-centric model, which proved to be predictors of successful program implementation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH BEHAVIOR OR POLICY

To increase the likelihood of program success, schools should consider how school infrastructure, personnel availability and school goals33 might affect program implementation. Schools should allocate a dedicated staff person to implement health promoting programs to ensure success. Selecting programs, such as FUTP60, that provide grant funds can prevent over-burdening the school and program advisor and can empower students to engage in the program. Additionally, capitalizing on student enthusiasm through the use of student-led teams36 could be a key to improving program implementation and reducing the burden on school staff. Finally, identifying programs that align with existing school goals is essential to the success of any school-based program.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The study was found to meet program evaluation criteria by the Colorado Multiple Institution Review Board (COMIRB). Studies that meet program evaluation criteria do not require further COMIRB approval.

Acknowledgements

Funding support was provided by the Dairy Research Institute (DRI) and Western Dairy Association (WDA). We also acknowledge Dairy Management Incorporated (DMI) and WDA for providing background information on FUTP60 and for providing the School Wellness Investigation and Program Utilization Surveys from participating schools. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official DRI, DMI, or WDA views.

Conflicts of Interest Declaration

This study was funded by the Dairy Research Institute (DRI). DRI was not involved in the following aspects of the study: design and conduct of the study, or collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data. DRI was involved in reviewing the manuscript in order to aid in identifying any factual errors regarding the original design and purpose of the Fuel Up to Play 60 program.

Contributor Information

Jimikaye Beck, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, Aurora, CO.

Lisa H. Jensen, Community-Campus Partnership, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

James O. Hill, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, Aurora, CO.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Environmental Health and Information and Statistics HSS. Colorado’s 10 Winnable Battles: Obesity. 2014. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/portals/1/documents/health/CUrbinaWB612.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 3.Chen YC, Tu YK, Huang KC, et al. Pathway from central obesity to childhood asthma. Physical fitness and sedentary time are leading factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 189(10):1194–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelsey MM, Zaepfel A, Bjornstad P, Nadeau KJ. Age-related consequences of childhood obesity. Gerontology. 2014;60(3):222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuemmeler BF, Pendzich MK, Tercyak KP. Weight, dietary behavior, and physical activity in childhood and adolescence: implications for adult cancer risk. Obes Facts. 2009;2(3): 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook S, Kavey RE. Dyslipidemia and pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(6):1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroebele N, McNally J, Plog A, et al. The association of self-reported sleep, weight status, and academic performance in fifth-grade students. J Sch Health. 2013;83(2):77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly JE, Lambourne K. Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Prev Med. 2011;52(Suppl 1):S36–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kibbe DL, Hackett J, Hurley M, et al. Ten Years of TAKE 10!((R)): Integrating physical activity with academic concepts in elementary school classrooms. Prev Med. 2011;52(Suppl 1):S43–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cawley J, Frisvold D, Meyerhoefer C. The impact of physical education on obesity among elementary school children. J Health Econ. 2013;32(4):743–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biddle SJ, Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2011. ;45(11):886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacka FN, Ystrom E, Brantsaeter AL, et al. Maternal and early postnatal nutrition and mental health of offspring by age 5 years: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(10):1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florence MD, Asbridge M, Veugelers PJ. Diet quality and academic performance. J Sch Health. 2008;78(4):209–215; quiz 239-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradlee ML, Singer MR, Qureshi MM, Moore LL. Food group intake and central obesity among children and adolescents in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Public Health Nutr. 2010; 13(6):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobol-Goldberg S, Rabinowitz J, Gross R. School-based obesity prevention programs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013; 21 (12) :2422–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khambalia AZ, Dickinson S, Hardy LL, et al. A synthesis of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based behavioural interventions for controlling and preventing obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):214–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleason PM, Dodd AH. School breakfast program but not school lunch program participation is associated with lower body mass index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(Suppl 2):S118–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox MK, Dodd AH, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Association between school food environment and practices and body mass index of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(Suppl 2):S108–S117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masse LC, de Niet-Fitzgerald JE, Watts AW, et al. Associations between the school food environment, student consumption and body mass index of Canadian adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014; 11 (1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wordell D, Daratha K, Mandal B, et al. Changes in a middle school food environment affect food behavior and food choices. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murtagh E, Mulvihill M, Markey O. Bizzy Break! The effect of a classroom-based activity break on in-school physical activity levels of primary school children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2013;25(2):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erwin HE, Beighle A, Morgan CF, Noland M. Effect of a low-cost, teacher-directed classroom intervention on elementary students’ physical activity. J Sch Health. 2011. ;81 (8):455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahar MT, Murphy SK, Rowe DA, et al. Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(12):2086–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD007651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuel Up to Play 60 LLC. Fuel Up to Play 60: 2012 Survey Results. 2014. Available at: http://school.fueluptoplay60.com/welcome/survey-results-2011-2012.php. Accessed November 12, 2014.

- 27.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity within a Generation. 2010. Available at: http://www.letsmove.gov/sites/letsmove.gov/files/TaskForce_on_Childhood_Obesity_May2010_FullReport.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuel Up to Play 60 LLC. School Wellness Investigation. Available at: https://school.fueluptoplay60.com/game-plan/survey-field/. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 30.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH, Murray N, et al. Dissemination and adoption of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH): a case study in Texas. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001;7(2):90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franks A, Kelder SH, Dino GA, et al. School-based programs: lessons learned from CATCH, Planet Health, and Not-On-Tobacco. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(2):A33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuel Up to Play 60 LLC. Nutrition Education Resources. Available at: https://school.fueluptoplay60.com/tools/nutrition-education/school-nutrition.php. Accessed November 24, 2014.

- 35.Dino GA, Horn KA, Zedosky L, Monaco K. A positive response to teen smoking: why N-O-T? NASSO Bulletin. 1998;82:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stock S, Miranda C, Evans S, et al. Healthy Buddies: a novel, peer-led health promotion program for the prevention of obesity and eating disorders in children in elementary school. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos RG, Durksen A, Rabbanni R, et al. Effectiveness of peer-based healthy living lesson plans on anthropometric measures and physical activity in elementary school students: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eskicioglu P, Halas J, Senechal M, et al. Peer mentoring for type 2 diabetes prevention in first nations children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronsley R, Lee AS, Kuzeljevic B, Panagiotopoulos C. Healthy Buddies reduces body mass index z-score and waist circumference in Aboriginal children living in remote coastal communities. J Sch Health. 2013;83(9):605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]