Abstract

Changes in family systems that have occurred over the past half century throughout the Western world are now spreading across the globe to nations that are experiencing economic development, technological change, and shifts in cultural beliefs. Traditional family systems are adapting in different ways to a series of conditions that forced shifts in all Western nations. In this paper, I examine the causes and consequences of global family change, introducing a recently funded project using the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and U.S. Census Bureau data to chart the pace and pattern of changes in marriage and family systems in low- and middle-income nations.

Keywords: family change, marriage and cohabitation, class differences in family structure, transition to adulthood

Global Family Changes

I still vividly recall from my graduate student days at Columbia University more than a half century ago noted sociologist William J. Goode strutting around the lecture hall complaining that we do not have a good general theory about why and how family systems are changing globally. Of course, he didn’t use the term “globally” explicitly because the word was not yet in fashion. In the mid-1960s, Goode made the theoretical argument that there would be a transformation in family systems around the world, from longstanding traditional forms to the “conjugal household.” With this term he was suggesting that family systems around the world would eventually converge with the Western model of the nuclear family—comprised of a married couple and their children in a single household, rather than multigenerational or complex households. Goode contended that the conjugal family was most compatible with the growth of market capitalism and a job-based economy. Consequently, he speculated that the Western system would eventually spread across the globe. Evidence of rapid economic growth and the development of a modern economy that have come to be called “globalism” had already moved beyond the West in the early post-War era to parts of Asia, just as Goode was completing his book World Revolution and Family Patterns (1963), which contained data from 50 countries and analyzed the impact of family on societies.

In what became a classic analysis of change in family systems, Goode (1963) assembled a large array of extant data describing recent patterns in a number of the world’s regional family systems. He convincingly demonstrated that over time, traditional agricultural-based economies and the family systems to which they had given rise were being undermined by the growth of job-based economies and the spread of Western ideas. At the same time, family patterns that had been in place around the globe were yielding to more Western-style practices such as the growing expectation of strong marital bonds, lower fertility, and fewer intergenerational households.

Goode (1963) argued that the Western family system had changed to fit (adapt to) an economy that increasingly required more education and geographical mobility. These changes in turn would erode the authority of family elders and reduce their formal control over their children, he asserted. Modern family systems in the West, he predicted, would initiate free mate choice based on compatibility and sentiment rather than on family interests or parental control. Finally, he showed that these modern features of Western family systems were being adopted in many regions of the world in the aftermath of the World War II.

Had Goode (1963) been able to imagine the revolution in gender roles that was also just on the horizon, he might have pointed to it as another major change in family systems. However, he was largely unable to foresee the events of the next several decades whereby the gender-based division of labor still observed in the West in the 1960s would give way to a growing demand for gender equality, although he hinted at this possibility (see Cherlin, 2012; Furstenberg, 2013). More recently, some theorists have examined the weakening of gender stratification as an independent source of family adaptation to economic growth (Esping-Andersen, 2009; Esping-Andersen & Billari, 2015; Goldscheider, Bernhardt, & Lappegard, 2015; McDonald, 2000).

Nonetheless, Goode’s masterwork (1963) influenced the writing of the next generation of sociologists and demographers who studied global and regional patterns of change in family systems. Although his theoretical perspective included the possibility that ideational change (i.e., a shift in cultural values) might precede or follow structural changes in family systems, a number of theorists, in response, emphasized and even prioritized the importance of value change through social diffusion (e.g., see Coale & Watkins, 1986; Hendi, 2017; Johnson-Hanks et al., 2011; Watkins, 1990) Just as Max Weber (1905) argued in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism more than a century earlier, these theorists have argued that culture is an independent influence on changing preferences for individual choice, a value set that is often seen as an export from the West. However, researchers—Caldwell, 1976; Inglehart, 1990; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn, 1988; Thornton, 2001; Van de Kaa, 1987; among others—have challenged the underlying assumption of economic determinism that they saw in Goode’s theory.

In a book on changing family systems titled Between Sex and Power: Family in the World—in some sense a sequel to Goode’s (1963) book from 40 years earlier—Therborn (2004) argued for the separate influence of law and public policy as an independent institutional driver of change both in the developed and developing worlds. Others have pointed to the potentially causal influence of changing demographic pressures owing to declines in mortality and fertility that prompted changes in the timing of life events such as marriage and childbearing ages (Bianchi, 2014; Bongaarts, 2015; Bongaarts, Mensch, & Blanc, 2017; Hertrich, 2017). Along the same line, reproductive technology has brought about new possibilities in the timing and organization of the life course, indicating that technology can also have an independent influence on change in family patterns (Golombok et al. 1995; Inhorn, Birenbaum, & Carneli, 2008).

These broad theories of why and how family systems change have stimulated a sizeable body of national and regional studies on patterns of family change throughout the world (Allendorf & Pandian, 2016; Amador, 2016; Cuesta, Rios-Salas, & Meyer, 2017; Kumagai, 2010; Kuo & Raley, 2016; Seltzer, 2004; Seltzer et al., 2005; Thornton et al., 2014; etc.). Yet, it is still fair to say that since the publication of Goode’s (1993) book more than a half century ago, there has been no systematic attempt to test in the broadest sense his theory of how change in family systems occurs or the competing explanations that have been advanced in response to his bold predictions using demographic data on a global scale.

Nonetheless, the idea of a growing convergence in fertility patterns has become a major topic of inquiry among demographers and economists (Casterline & National Research Council, 2001; Coleman, 2002; Crenshaw, Christenson, & Oakey, 2000; Dorius, 2008; Hendi, 2017; Rindfuss, Choe, & Brauner-Otto, 2016; Wilson, 2001, 2011). Even taking account of this distinct line of research, a broader investigation of how and why family systems change over time, much less the systematic testing of Goode’s broad theory and the responses to it, has been stymied by the absence of comparable data on global family systems. The availability of such data would permit the empirical examination of competing explanations of the transformation of family systems in response to economic, cultural, social, demographic, and political change.

This paper examines some of the issues that must be addressed before family scholars can develop and test theoretical explanations for why and how family systems change. I begin by enumerating the major changes that have occurred in families across the globe, before introducing a conceptual framework for investigating why change is coming about more rapidly in some regions of the world than in others. After describing why systems are changing, I turn to a particular feature of the change: growing patterns of inequality that are being generated by diverging family patterns across social class strata. Finally, I conclude by describing an ongoing project through which colleagues and I are assembling extensive and reliable data to study these issues.

Worldwide Changing Family Practices

Broadly speaking, it is easy to argue that some degree of convergence in family patterns worldwide, as presented below, has already occurred, particularly if the terrain is restricted to marriage and fertility, although researchers have noted continuing evidence of heterogeneity as well (Holland, 2017; Pesando & the GFC team, in press).

The age at first marriage has been rising in most nations of the world (Jones & Yeung, 2014). This pattern was evident in Western Europe and English-speaking countries during the latter third of the last century and has continued into the present (Stevenson & Wolfers, 2007). It is now evident that similar changes have occurred more recently in virtually all countries in Eastern Europe, large areas of East Asia (with some important exceptions. such as much of India, China, Indonesia, and Vietnam), and part of Africa and Latin America (Bongaarts, Mensch, & Blanc, 2017; García & de Oliveira, 2011; Harwood-Lejeune, 2001; Raymo et al., 2015). Although not uniform, the pattern is sufficiently widespread to lead most researchers to conclude that the institution of marriage is undergoing profound changes in most parts of the world in response to economic and social change (Cherlin, 2012).

The rise in the age at first marriage is just one reason for the general decline in fertility that has occurred worldwide except in rural Africa and parts of the Middle East (Bongaarts, 1978; Casterline, 2017; Madsen, Moslehi, & Wang, 2018). As I have already noted, marriage at a later age typically implies less family influence on the choice of partner and perhaps a growth in heterogamous unions, at least initially, as individuals have more options to form families of their own choosing, including remaining single. This pattern has increased in most nations, especially where females have entered the labor force in greater numbers (Esteve, Garcia-Roman, & Permanyer, 2012; Harknett & Kuperberg, 2012). In some family systems, particularly in the economically advanced nations of East Asia, a growing fraction of women seem to be exercising their option to delay marriage indefinitely (Furstenberg, 2013; Jones, 2005; Raymo et al., 2015). As in the West, marriage is apparently becoming more discretionary in Eastern Europe and parts of Asia (Jones, Hull, & Mohamad, 2011; Thornton & Philipov, 2009).

As marriage has become more optional, the practice of cohabitation (before, after, or in lieu of a formal union) has grown throughout the Western world and in Eastern Europe (Heuveline & Timberlake, 2004; Holland, 2017; Lundberg, Pollak, & Stearns, 2016; Thornton & Philipov, 2009). In many nations in Latin America and the Caribbean, where cohabitation has long been a preferred form among certain ethnic and racial minorities, it has become more widely practiced among more economically advantaged individuals who previously confined their unions to formal marriage (Covre-Sussai et al., 2015; Esteve & Lesthaeghe, 2016; Esteve, Lesthaeghe, & Lopez-Gay, 2012; Lesthaeghe, 2014).

Divorce after marriage has become more common in most nations, especially those with previously low rates of marital dissolution (Surkyn & Lesthaeghe, 2004). While marital stability has increased in some countries among the most educated, it has declined at the same time for the less educated and skilled portion of the population (Schwartz & Han, 2014). As marriage has moved to a more companionate form, divorce is increasingly viewed as an acceptable option for couples in unsatisfactory relationships (Goode, 1963; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2004).

A concomitant trend is the growth of childlessness in families in most wealthy nations, which is associated with declining fertility (Kreyenfeld & Konietzka, 2017; Rowland, 2007). In a growing number of nations in Europe, the English-speaking nations, and the advanced economies of Asia such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, substantial proportions of women are electing not to have children (and often not to marry (Jones, 2007). Living alone has become more common in many countries of the world as growing numbers of females have entered the labor force and opted not to marry (Jones, 2005). Childlessness appears to be on the rise in East Asia and other rapidly developing parts of the globe.

The rapid growth of women’s participation in the labor force in most developing and almost all developed nations has been accompanied by a change in men and women’s domestic roles (Goldscheider, Bernhardt, & Lappegard, 2015; McDonald, 2000). In many nations, the ideology of gender equality may have grown faster than its actual practice. Nonetheless, throughout the developing and developed world, a push for women’s rights has meant that females now have far more access to education and labor market participation in the 21st Century (Duflo, 2012; Goldin, 2006). And, this trend is only likely to increase as women’s rights are enforced by changes in legal statutes and public policies. Moreover, spousal beating and sexual coercion have been identified as serious problems in countries that at one time legitimized these practices (Yount, 2009).

The weakening of the institution of marriage has been accompanied by a growing tolerance for premarital sexual behavior and out-of-wedlock childbearing (Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2004). Although much of the non-marital childbearing is occurring within informal unions, the stability of non-marital unions with children is lower than marital unions with children (Manning, Smock, & Majumdar, 2004). This particular trend may be contributing to the growing stratification in family systems between the advantaged and disadvantaged. The privileged are more likely to marry and have children after marriage, whereas those less well-off are having them before or outside of marriage, contributing to a perpetual economic and social disadvantage (Kalil, 2015; Lundberg, Pollak, & Stearns, 2016; McLanahan, 2004). It is worth noting that in parts of the developing world, the pattern of consensual marriages has long existed, particularly in Latin America and the West Indies (Esteve & Lesthaeghe, 2016).

The stratification of family systems is both a cause and consequence of rising levels of inequality in most nations with advanced economies, and introduces profound differences in children’s opportunities. Among the educated, children are more often the products of intense investment; less educated parents often lack both the resources and the skills to prepare their children for a more demanding educational system in order to acquire the knowledge and skills needed today (Dronkens, Kalmijn & Wagner, 2006; Schneider, Hastings, & LaBriola, 2018). In all likelihood this pattern is appearing in developing nations (Kalil, 2015; Pesando & the GFC team, in press).

Although preferences for intergenerational arrangements continue to prevail in some parts of the world, individuals forming families are increasingly less likely to reside in conjoint and complex households (Ruggles & Heggeness, 2008). The decline of intergenerational households in some nations may also reflect the declining influence of the older generation; in at least some of these nations, there is concern that the elderly may lack traditional family support in later life (Grundy, 2006; Taylor et al., 2018).

These trends in marriage and family do not generally occur singly as family systems change from agricultural-based to industrial- and post-industrial based economies. They typically evolve as interrelated changes that co-occur over time, although not necessarily in a predictable or orderly sequence of adaptations to exogenous changes in the economy, polity, technological advances, and alterations in the culture of a society. Demographers have referred to these related features as the second demographic transition (Lesthaeghe, 2010, 2014; McLanahan, 2004). By this they mean that family systems have become more governed by members’ individual preferences than by elders (especially males) who once assumed considerable authority to impose their will on the family as a collective system. As Therborn (2004) argued, the decline of patriarchy appears to be at the core of family system change, although it cannot be considered a cause of it in the strictest sense of the word. More accurately, as I assert in the next section, the changes are brought about by a host of factors that work in tandem to undermine the existing order that is often based on patriarchal expectations.

Why Change Occurs in Family Systems

The transformation of family systems in many regions of the world and in particular nations has been amply documented by demographers, sociologists, and economists cited earlier according to some of the trends just described, but this transformation has not been explained in a strict sense. It is clear that the development of a job-based economy is one of the central sources of change, much as Goode (1963) claimed a half century ago. However, economic development does not take place in isolation from broader societal changes, that is, institutional changes in education, health, law, and the spread of technology alter existing institutions and longstanding cultural assumptions (Meyer et al., 1975).

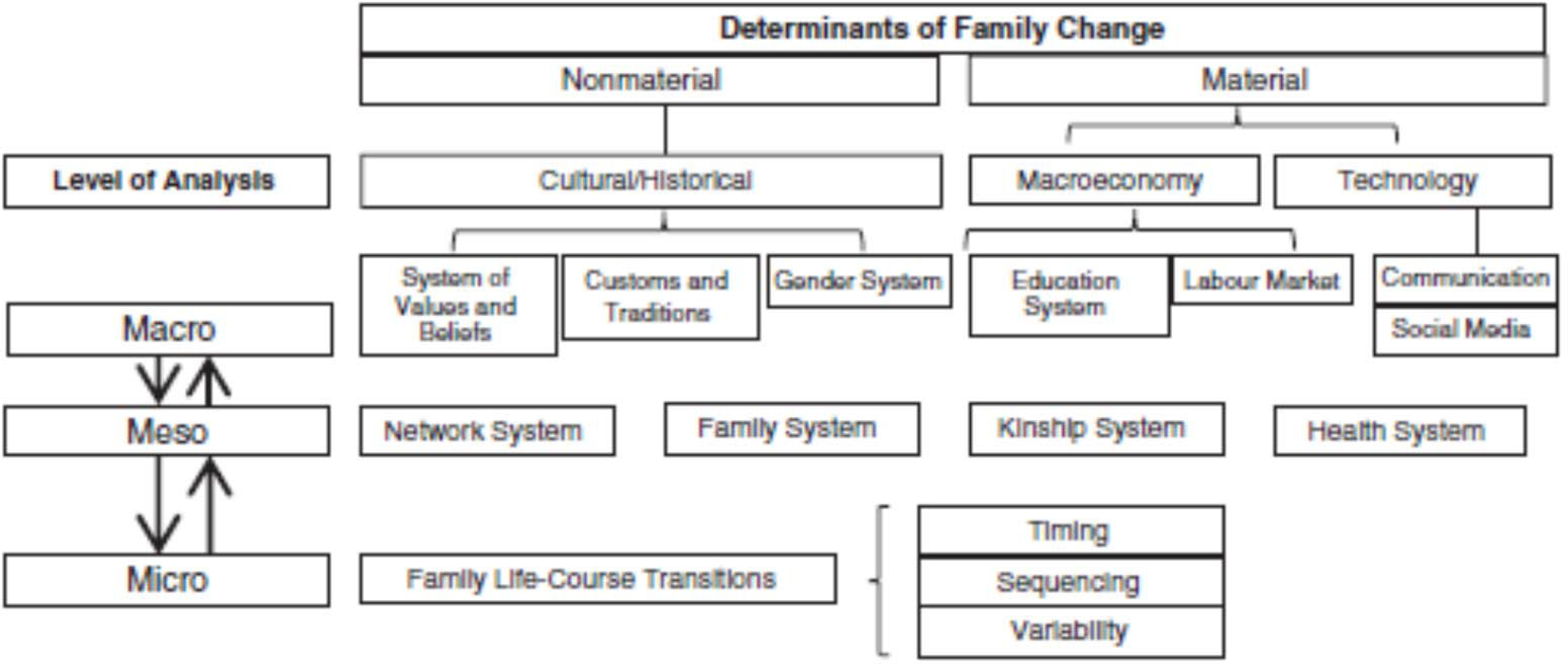

To illustrate, I have borrowed a conceptual scheme that depicts some of the sources of social change from an ongoing research project funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) that is designed to examine this process in family systems across the globe and is being carried out by a team of scholars at the University of Pennsylvania, including Hans-Peter Kohler (Project Head), Luca Maria Pesando, Andres Castro, and collaborators in several European nations (see http://web.sas.upenn.edu/gfc; Pesando & the GFC team, in press). Using data from the worldwide Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), the Global Family Change (GFC) Project has extracted indicators of family change to identify patterns of change in low- and middle-income countries and test the processes by which family system change occurs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Determinants of Family Change.

In this research project, my colleagues and I make a fundamental assumption that alterations in family patterns can arise from societal adaptations to a number of different exogenous sources introduced into a society through parallel and often complementary processes. Change in family systems often comes about when transformations in macro-level conditions occur; the most important of these being the transition from a predominately traditional subsistence economy to a production-oriented economy transformed by its capacity to provide exports to agro-business, manufacturing, and industry. This transformation, much as Goode (1963) argued, creates or expands a job-based economy that favors younger and more geographically mobile individuals, including young and typically unmarried women. Economic development is typically centered in urban areas, implying a shift from a rural to an urban population, bringing about a loss of family control, especially when young people in cities often continue to support their kin financially in the countryside.

Such economic developments do not invariably go hand in hand with shifts in cultural expectations and practices, but it is not uncommon to see, especially among the young, a reorientation to more individually-determined lifestyles and a decline in social control by elders, and especially in men’s control of women (Cherlin, 2012). Quite independently, economic development introduces new technologies (Greenwood, 2019). The rapid spread of the use of computers and smart phones has stimulated a growth in the use of social media in developing nations, a powerful influence on younger persons who have quickly adopted these new forms of communication (Pew Research Center, 2018). So, exposure to social influences begins to extend well beyond the family, village institutions, or even national political sources of opinion. Inevitably, peer-mediated contexts begin to hold more weight on public opinion, and the extended family system loses influence accordingly (Allendorf, 2016; Bongaarts & Watkins, 1996; Cherlin, 2012).

Accompanying and preceding economic development also come alterations in existing political, social, and even religious institutions. The educational system becomes both a channel of mobility and in many nations a new way that families can maintain or achieve advantage if they choose to invest in their children’s long-term futures through schooling. The importance of schooling grows as it extends from primary to secondary institutions, and ultimately to tertiary education for the affluent and the talented. Education itself often presents a powerful counterweight to traditional practices both inside and outside the home, upsetting longstanding cultural understandings. For women, whose presence in secondary and tertiary education has grown to a majority in many countries, the impact of additional schooling can be transformative, eroding traditional gender norms and giving economic advantages to more educated women (Esteve, Garcia-Roman, & Permanyer, 2012; Schwartz & Han, 2014).

In the polity and the public sphere, shifts in the opinions of economic and political elites often must take account of the changed economic status of women that comes with education and greater involvement in the labor market. Relatively little is known about the timing of broad institutional changes that bring about women’s greater involvement in the polity. And, lacking systematic data, little is known about how gender involvement in education and work plays out inside the family. Alternatively, changes within family systems may occur in response to cultural ideas about equality that travel through different routes such as mass and social media or come about because of legal or policy changes. Political leaders advocate and adopt new policies that often are imported from rich nations or more economically developed neighbors in the region (Meyer, 1975; Watkins, 2001). New ideas and practices may be imported, but they are typically modified to suit the institutional structures in place and mediated by national traditions and culture that tailor and shape them to conform to existing cultural forms. New policy dilemmas arise in the process of economic development, with the dissemination of new forms of technology, and the spread of cultural ideas and information. Invariably, certain countries must support or ban new reproductive technologies, the content of Western movies and social media, and laws regulating same-sex marriage. Thus, disagreements over public policies related to these practices and issues can happen rapidly, and we suspect independently, of the level and pace of economic development.

It is wrong to assume that the process of economic and social development works invariably from the top down, with those having more education or resources always adopting new family patterns sooner than the rest of the population, but this flow from the well off to the less privileged often occurs (Pesando & the GFC team, in press). Changes can simultaneously occur at the macro, mezzo, and micro levels; values can and do change as individuals move from the countryside to the city, or leave their home countries to find work elsewhere (Hu, 2016). Increases in migration to and from other nations are undoubtedly a source of new information, values, and daily practices. Ideas are promulgated through channels of mass and social media that promote educational advancement, individual fulfillment, or gender equality, undermining traditional family patterns sometimes even in nations that are lagging in economic advancement.

At the individual level, change occurs as people confront new and unfamiliar situations as they occur or, at least, are imaginable (such as going to a university, engaging in sex before marriage, or migrating to another country for employment). As Mills (1959) observed decades ago in The Sociological Imagination, cultural contradictions emerge in all societies experiencing change, that compel individuals to adopt new ways of thinking and new forms of behavior. Nowhere is this more evident than in the change that occurs within family systems as older practices no longer seem to have the same cultural grip that they once had. One only has to think about how many people have begun to eschew formal marriage today in the West, adopting social practices such as cohabitation or single parenthood or gay marriage, that were socially unacceptable, even unthinkable, a half century ago (Biblarz & Savci, 2010; Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013).

In sum, social change is an organic and systemic process that permeates a society and its existing institutions. And at the micro-level of individuals and families, it is received or resisted by the powerful and powerless alike. It will not take precisely the same form in all nations because it is mediated by a nation’s historical experience, its cultural priorities, and existing institutional arrangements (Cook & Furstenberg, 2002). Thus, the process of change will vary, producing both similar and dissimilar responses, depending on existing political/historical experience, cultural, and social arrangements. This is why Billari and Liefbroer (2010) asserted that there can be a convergence to divergence when describing patterns of family change.

Where and When Changes in Family Systems Occur

It should be evident from my previous descriptions of the complex and variegated nature of how changes in family systems occur that new patterns and practices are adopted unevenly both across and within various nations. A major reason why the pattern of change is not uniform is that exposure to both economic and cultural changes differs depending on the specific social contexts in which individuals and their families are embedded. Think, for example, of the vast differences in exposure to these changes that living in a capital city of a developing nation versus in a remote area might mean. This is aptly illustrated by the changes in attitude about marriage now occurring in Vietnam where attitudes about marriage timing, cohabitation, and premarital sex differ widely from countryside to urban environments (Minh & Hong, 2015).

A second source of variability in family system changes is that receptivity to new ideas or practices will vary depending on such factors as age, gender, education, ethnic and religious affiliations, and a host of other conditions. For example, adoption of new methods of contraception, say by young unmarried women, can be a sensitive indicator of what might be called a predisposition to modernity when the logic of having large numbers of children becomes questionable for some in a society but not for others. As I have already noted, there are powerful differences in the stakes of adopting new practices that threaten to undermine the way things have long been done in any developing nation. Any adequate theory purporting to explain family system change must account not only for the total change but also for the variable levels of change within a nation.

Historians of family change in the West have made this point repeatedly in noting that change is uneven in any given nation. Such was the case with Protestants in England during the 16th century who were more open to changing childrearing practices to emphasize a child’s relationship to God than were Catholics (Stone, 1977). The upper classes also adopted new and different ideas concerning childrearing, owing to religious ideology and education than did the rest of the population. Several centuries ago in Western Europe and the United States, urban residents and young people in general were more receptive to growing preferences for individualism and the rise of sentiment in family relationships than were their rural and older counterparts (Shorter, 1977). Similarly, in the developing world today, some groups will be more welcoming of certain new practices than others, depending on the degree to which they are embedded in certain institutional contexts that reinforce a commitment to existing family patterns. Any adequate theory of family change must account for both where it takes hold and how its spreads within nations. The analysis of big data generated by patterns of media use, for example, is potentially an attractive source of information for investigating how change runs through established and new social networks in the developing world.

In early stages of economic and social development, increasing variability in family behaviors within a developing nation is to be expected as new family patterns such as premarital sexual behavior and marriage delay are adopted unevenly, let’s say between rural and urban areas, the more and less educated, or, for example, among some ethnic groups and not others. Over time, this variability may decline as practices become more widely accepted and diffused. But note how differences in family patterns may also persist for long periods of time. One only has to think about how enduring differences have been observed in Europe between the Northern and Southern nations (Perelli-Harris, 2014), or the continuing variation between family patterns such as cohabitation, family size, or the prevalence of intergenerational households in Northern and Southern Italy (Gabrielli & Hoem, 2010).

Economic Inequality and Family Systems

Adaptation to macro-level changes in the economy or mezzo-level changes that occur within institutions creates new winners and losers in the developing world, as has happened in the past in nations with advanced economies (see www.welfare.org). I have argued elsewhere that an interaction is occurring between changing family systems and growing economic inequality, which has been a trend in virtually all post-industrial economies and many rapidly developing nations (Furstenberg, 2011, 2013). It is not difficult to imagine why and how family change is amplified by economic divergence and vice versa. For example, educational attainment can be assumed to weigh more heavily on outcomes in economies that utilize advanced skills and knowledge; access to education, especially higher education, may in turn affect the process of family change (Esping-Anderson, 2016).

In the United States and many nations in Europe, destinies among the well off and the not so well off began to diverge in the latter decades of the 20th century as the nuclear family became increasingly important as both an agency of socialization and parental management of children (McLanahan, 2004). Family forms, such as whether parents marry or even reside together at the time of birth, birthing procedures, maternal health, breastfeeding, styles of parenting, and different abilities of families to manage and place their children in contexts that promote (or diminish) opportunity have new and perhaps more lasting effects than they might have had in the past. Parents’ influence on school performance appears to be growing in societies where educational attainment has become a more important criterion for success in later life. In rich nations, poorer families and middle-income families have begun to fall behind their wealthier counterparts in promoting their children’s level of schooling (Lareau, 2011). Children receiving less intense socialization and particularly preparation for schooling may have fewer potential paths in life than their more educated counterparts to make it into the middle class.

Nations substantially differ in their commitments to reducing the disparities created in advanced economies through the redistribution of public resources and development of policies that attempt to reduce and offset the powerful early influences on children’s development that are associated with lower social class position. Limited efforts by some nations, such as the United States, to mitigate the potent effects of family patterns of socialization have created substantial gaps in children’s life chances (Smeeding, 2006), which is an evitable result of the great differences in resources and the capabilities of parents in many contemporary societies to place their children in settings that will provide them with the skills and training to enter and succeed in school.

The evidence that social class disparities in family systems are growing globally has not been established despite the fact that inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has grown in all but a few nations over the past several decades (Bowles, Gintis, & Groves, 2008). And there are indications of shifts in family practices, such as marriage and non-marital childbearing, that may be diverging at the top and bottom of the socioeconomic ladder in some Western nations, most notably the United States (Cherlin, 2010; Lundberg, Pollak, & Stearns, 2016; McLanahan, 2004). However, this divergence in family patterns is also evident in some European nations and may be appearing in certain rapidly developing countries in East Asia (Bernardi & Boertien, 2017; Harkonen, 2017).

Although certainly occurring elsewhere, evidence for a widening of social class in family behaviors is most apparent in the United States, where over the past 30 years or more, Americans have lost ground in creating conditions that ensure equality of opportunity—an ideal that Americans have long believed is essential to maintaining a just society (Chetty et al., 2014; Corak, 2013). Class differences in family patterns have widened on a variety of fronts even as family variations among racial and ethnic groups have shrunk (Reardon, 2011). In fact, I would contend that Americans now have a two-tiered family system—a system where family patterns among rich and poor have begun to diverge even more sharply than they did a half century ago when sociologists first documented considerable variation (Furstenberg, 2013).

At the bottom and increasingly in the middle of U.S. income distribution, marriage is occurring less often before the transition to parenthood (Lundberg, Pollak, & Stearns, 2016). Many births are less likely to be planned and often occur in ephemeral partnerships; a growing number of lower-income couples are having children from more than one union, a pattern that has come to be known as multi-partnered childbearing (Fomby & Osborne, 2017; Guzzo, 2014). This emerging trend of couples having children in two or more unions means that parents, fathers in particular, are dividing their investments of time, money, and emotion among their children in multiple households, and many are growing up in households where fathers (and less often mothers) come and go (Thomson, 2014).

Of course, certain benefits could be gained when children can rely on several parent figures, but they are only likely to occur when the parents are deeply invested (spend time, money, and emotion) in the lives of both their biological and non-biological offspring (Akashi-Ronquest, 2009; Henretta, Van Voorhis, & Soldo, 2014). Evidence suggests that fathers in these circumstances often lack the resources to meet their parental obligations even if they have the desire to do so (Berger, Cancian, & Meyer, 2012). Presently, little is known about the enduring commitments of parents who do not reside with their biological children and the behaviors of surrogate parents who replace them in the household (Carlson & Furstenberg, 2006; Hans & Coleman, 2009). However, most of what is known about the importance of stability, stimulation, and emotional bonds in early life suggests that children’s development may be compromised in conditions where there is a high family flux arising from the absence or replacement of biological parents (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007).

Beyond the form of the family and parenting processes in early life, parents’ ability to channel resources to their children matters both early and later in life. Support by extended family members can sometimes help to mitigate the absence of parental resources. However, research on the flow of intergenerational resources suggests that children from privileged families provide far more assistance to their children and grandchildren than occurs in poor families where resources are in short supply. Indeed, the gap between rich and poor children grows in part because wealthier grandparents are better positioned to help out by providing housing assistance and child support when needed (Albertini, Kohli & Vojel, 2007).

A host of advantages for children are strongly associated with adequate income and education. Just to mention a few, children in privileged families (those whose parents have a college education) live in more desirable neighborhoods with better schools, libraries, and recreation facilities, and in these preferred contexts, they are more likely to have supervised peer relationships with children of other privileged families in preschool and afterschool programs or during the summer (Lareau, 2011; Minh et al., 2017; Schneider, Hastings, & LaBriola, 2018). Lower-income parents cannot afford these amenities unless the programs are publically funded or subsidized, which for the most part does not happen in most low-income communities in the United States (Esping-Andersen, 2016).

Thus, it is not surprising to discover that substantial differences exist between the better off and less well off in preparation for schooling, and that these initial differences only widen over time because many children enter school systems that are ill-equipped to compensate for the disadvantages of growing up poor (Alexander et al., 2014). A large body of research has documented how stratification in family practices is creating trajectories of disadvantage in middle and later childhood, during adolescence, and, more recently in early adulthood (Furstenberg, 2011).

The reverse image of this cycle of disadvantage occurs when children are born into well-off families in American society. Even before birth, the situations of advantaged families have sharp, positive differences at birth. Childbearing is highly likely to occur within a marital union, where the relationship has often been time-tested (Upchurch, Lillard, & Panis, 2002). Not infrequently, the partners have been cohabitating and enter marriage because they are ready to have children (Sassler & Miller, 2011). Women in higher income groups receive prenatal care more often (Osterman & Martin, 2018); they are less likely to smoke, drink to excess, and more often adhere to healthy diets (Furstenberg, 2010; Pampel, Denney, & Krueger, 2011). Thus, children born into privileged families enter life in better health and with parents who are well prepared to keep them healthy and thriving. Their homes and neighborhoods are safer so that children in affluent and educated families are less at risk of having accidents or suffering stressful experiences. Moreover, they have better chances of receiving therapeutic interventions when negative events do occur (Duncan et al., 1998).

Parental socialization practices differ sharply by socioeconomic status in ways that also favor the better off. A long tradition of research by developmental psychologists and family sociologists has shown that better educated and wealthier parents have the resources to instruct their children in ways that prepare them to succeed in school (Yamamoto & Sonnenschein, 2016); moreover, these parents are more confident and skilled in communicating with teachers and school personnel when their child is not doing well (Ankrum, 2016). And, they possess the social capital to help place their offspring in advantageous educational and cultural settings when they are young and when they reach adolescence and early adulthood (Conley, 2001; Lareau, 2011).

Research both in the United States and abroad, following the important work of Lareau (2011), has identified the “concerted cultivation” provided to children by parents with more resources and education. Increasingly, the family has become a “hothouse for development” where parents have become ever more alert to strategies to assist their children from the cradle to career opportunities. These parents probably deploy more psychological, cultural, and social capital than in earlier eras when there was a more laissez-faire or informal approach to childcare and childrearing (Bianchi, 2011).

The United States is something of an outlier in the West when it comes to public services and support for children and families, especially lower-income families. Consequently, the class gradient in these families’ behaviors, such as non-marital and single parenthood, unintended pregnancies, prenatal care, neonatal services, preschool, and afterschool, may be more pronounced than in other English-speaking nations, Europe, and the wealthy nations of Asia. Forms of the family and family practices and processes have not yet been well studied in a cross-national context, much less a global one. However, countries have different tolerances for income inequality and different levels of commitment for public services to address social issues, particularly their impacts on children. Thus, it remains to be seen how much variation in these behaviors by social class exists in different wealthy nations.

A New Research Frontier

Despite widespread acknowledgement that family systems are changing rapidly in many parts of the world, research to understand the process (how and why change occurs) and the direction (adoption of patterns that have become common features of Western systems) of change is still in its infancy. There is growing availability of harmonized data sets that include many Western and some non-Western nations. Researchers have begun to analyze data from studies such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Family Database, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Generations and Gender Surveys (GGS), national birth cohort studies, Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and its counterparts, Harmonised European Time Use Survey (HETUS), and the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), among others. However, there are formidable problems to examining many of the issues that I have mentioned in this paper.

Sample sizes are sometimes too small to permit informative analyses, representativeness remains an issue in many data sets, the number of countries is rarely large enough to support multilevel comparisons, and contextual information on cultural values or public policies is absent. The research community has not yet fixed its sights on understanding how change in family systems occurs, where change takes place, and what features of culture and social structure mediate the direction of change. Most of all, there is a lack information on how public policies mitigate some of the consequences of family system change for individuals and households.

The Penn–Oxford Project on Global Family Change (GFC), which is designed to examine change on a global scale, is well underway. It utilizes data from more than 100 nations by converting national censuses and Demographic and Health Surveys that have been conducted over several decades (see www.dhsprogram.com). The aim of the GFC team is to convert the sources of information that are cross-sectional into life-course indicators (e.g., whether individuals are in school or not at different ages, whether they have married or have had children by different ages, and so on) that in turn will permit the GFC team to examine the tempo and sequence of family change over time. The GFC team is planning to create macro-level measures that can be appended to the various countries for which data exist to develop life-course indicators of change (Pesando & the GFC team, in press). This will allow examination of the influence, sequence, and order of family changes and the variating macro-level conditions that initiate these changes.

The attention of the GFC team will be on indicators of changing family patterns in the early part of the life course: change in the age of school leaving, home leaving, entrance to full-time employment, cohabitation, marriage, and first birth. But the team may also examine these indicators in combination to understand the sequence of family change such as childbearing outside of marriage, years of sexual activity outside of marriage, and the like. The intention is to identify associations between macro-level change (i.e., changes in the economy, cultural values, and technology) and the emergence of new family forms and changes in the process of family formation to examine how, why, and where change is taking place. The team will also be able to investigate whether evidence of emerging class differences in family patterns is occurring with the growth of inequality. By building a data set that contains macro-level data, evidence on changes in public policies, and measures of family change, we will be able to more systematically and rigorously test the web of associations suggesting potential chains of causal influence in processes that occur in family systems with the rise of new economies, technologies, and shifts in cultural priorities and practices.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have explored some of the challenges of examining how and why family systems are changing around the globe. I have discussed longstanding disagreements over the sources of change and why both convergence and divergence in family systems that are moving from agricultural-based to industrial-based economies should be expected. My account builds on the theory of the world’s family systems that William J. Goode (1963) proposed over a half century ago and that has yet to be subject to vigorous empirical examination. However, plans are underway to construct a global database at the University of Pennsylvania containing information that will permit researchers around the globe to map the pace and process of changes in family systems, focusing especially on the transition to adult status.

Throughout the world, the passage to adulthood is generally becoming more protracted and more discretionary. As a consequence, elders, especially men in traditional families, will lose influence over the direction of their children’s lives and the choices they make. The young and females in particular in much of the developing world are increasingly looking to education and employment as the means to personal advancement. This process will generally undermine family authority, although in its early stages, families are likely to continue to exert influence over mate selection in many nations where parental influence on marriage choice has been strong.

These changes are taking place in the context of growing economic inequality that is creating considerable divergences in family practices at the top and bottom of the socioeconomic distribution. Family systems in many nations with advanced economies are witnessing greater stability among the privileged while instability is growing in these same systems among the under-privileged. If not counteracted by public policies aimed at mitigating the impact of these divergent family practices within societies, a hardening of the stratification system that creates ever stronger barriers to social mobility can be expected in the developing world.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge support for this paper through the Global Family Change (GFC) Project (http://web.sas.upenn.edu/gfc), which is a collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania, University of Oxford (Nuffield College), Bocconi University and the Centro de Estudios Demograficos (CED) at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. Funding for the GFC Project is provided through NSF Grant 1729185 (PIs Kohler & Furstenberg), ERC Grant 694262 (PI Billari), ERC Grant 681546 (PI Monden), the Population Studies Center and the University Foundation at the University of Pennsylvania, and the John Fell Fund and Nuffield College at the University of Oxford.” I am indebted to Shannon Crane and Luca Maria Pesando for their helpful comments on the paper.

References

- Akashi-Ronquest N (2009). The impact of biological preferences on parental investments in children and step-children. Review of Economics of the Household, 7, 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Albertini M, Kohli M, & Vogel C (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: common patterns—different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17, 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K, Entwisle D, & Olson L (2014). The long shadow: Family background, disadvantaged urban youth, and the transition to adulthood. New YorkLocation?: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf K (2016). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 453–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf K, & Pandian RK (2016). The decline of arranged marriage? Marital change and continuity in India. Population and Development Review, 42, 435–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00149.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador JP (2016). Continuity and change of cohabitation in Mexico: Same as before or different anew. Demographic Research, 35, 1245–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Ankrum RJ (2016). Socioeconomic status and its effect on teacher/parental communication in schools. Journal of Education and Learning, 5, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Cancian M, & Meyer DR (2012). Maternal re-partnering and new-partner fertility: Associations with nonresident father investments in children. Child Youth Services Review, 34, 426–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi F, & Boertien D (2017). Non-intact families and diverging educational destinies: A decomposition analysis for Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States. Social Science Research, 63, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM (2011). Family change and time allocation in American families. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM (2014). A demographic perspective on family change. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6, 35–44. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz TJ, & Savci E (2010). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 480–497. [Google Scholar]

- Billari FC, & Liefbroer AC (2010). Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Advances in Life Course Research, 15, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J (1978). A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review, 4, 105–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, & Watkins S (1996). Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review, 22, 639–682. doi: 10.2307/2137804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J (2015). Global fertility and population trends. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 33, 5–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, Mensch BS, & Blanc AK (2017). Trends in the age at reproductive transitions in the developing world: The role of education. Population Studies, 71, 139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S, Gintis H, & Groves MO (2008). Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC (1976). Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory. Population and Development Review, 2, 321–366. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, & Furstenberg FF (2006). The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban U.S. parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Casterline JB, & National Research Council. (2001). Diffusion processes and fertility transition: Selected perspectives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casterline JB (2017). Prospects for fertility decline in Africa. Population and Development Review, 43(S1), 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 403–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2012). Goode’s world revolution and family patterns: A reconsideration at fifty years. Population and Development Review, 38, 577–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00528.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Hendren N, Kline P, Saez E, & Turner N (2014). Is the United States still a land of opportunity? Recent trends in intergenerational mobility, American Economic Review, 104, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, & Watkins SC (1986). The decline of fertility in Europe: The revised proceedings of a conference on the Princeton European Fertility Project. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DA (2002). Populations of the industrial world - A convergent demographic community? International Journal of Population Geography, 8, 319–344. [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, & Furstenberg FF (2002). Explaining aspects of the transition to adulthood in Italy, Sweden, Germany, and the United States: A cross-disciplinary, case synthesis approach. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 580, 257–287. doi: 10.1177/000271620258000111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corak M (2013). Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Covre-Sussai M, Meuleman B, Botterman S, & Koen M (2015). Traditional and modern cohabitation in Latin America: A comparative typology. Demographic Research, 32, 873–914. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw EM, Christenson M, & Oakey DR (2000). Demographic transition in ecological focus, American Sociological Review, 65, 371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta L, Rios-Salas V, & Meyer DR (2017). The impact of family change on income poverty in Colombia and Peru. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 48, 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dorius SF (2008). Global demographic convergence? A reconsideration of changing intercountry inequality in fertility. Population and Development Review, 34, 519–537. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo E (2012). Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50, 1051–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, & Smith JR (1998). How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review, 63, 406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G (2009). Incomplete revolution: Adapting welfare states to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G, & Billari FC (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G (2016). Families in the 21st century. SNS Förlag [Google Scholar]

- Esteve A, Garcia-Roman J, & Permanyer I (2012). The gender-gap reversal in education and its effect on union formation: The end of hypergamy? Population and Development Review, 38, 535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve A, & Lesthaeghe RJ (2016). Cohabitation and Marriage in the Americas: Geohistorical Legacies and New Trends, New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve A, Lesthaeghe RJ, & López-Gay A (2012). The Latin American cohabitation boom, 1970–2007, Population and Development Review, 38, 55–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, & Cherlin AJ (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review, 72, 181–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, & Osborne C (2017). Family instability, multipartner fertility, and behavior in middle childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF (2011). The recent transformation of the American family: Witnessing and exploring social change. In Carlson MJ & England P (Eds.), Changing families in an unequal society (pp. 192–220). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF (2013). Transitions to adulthood: What we can learn from the West. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 646, 28–41. doi: 10.1177/0002716212465811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli G, & Hoem JM (2010). Italy’s non-negligible cohabitational unions. European Journal of Population, 26, 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García B, & de Oliveira O (2011). Family changes and public policies in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 593–611. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C (2006). The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. American Economic Review, 96(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Bernhardt E, & Lappegard T (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41, 207–239. [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, Cook R, Bish A, & Murray C (1995). Families created by the new reproductive technologies: Quality of parenting and social and emotional development of the children. Child Development, 66, 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode WJ (1993). World changes in divorce patterns. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J (2019). Evolving households: The imprint of technology on life. Cambridge MA, The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E (2006). Ageing and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Ageing & Society, 26, 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2014). New partners, more kids: Multiple-partner fertility in the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 66–86. doi: 10.1177/0002716214525571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans JD, & Coleman M (2009). The experiences of remarried stepfathers who pay child support. Personal Relationships, 16, 597–618. [Google Scholar]

- Harknett K, & Kuperberg A (2011). Education, labor markets, and the retreat from marriage. Social Forces, 90, 41–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkonen J (2017). Diverging destinies in international perspective: Education, single motherhood, and child poverty. LIS Working Paper Series No. 713, Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood-Lejeune A (2001). Rising age at marriage and fertility is Southern and Eastern Africa. European Journal of Population, 17, 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hendi A (2017). Globalization and contemporary fertility convergence. Social Forces, 96, 215–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henretta JC, Van Voorhis MF, & Soldo BJ (2014). Parental money help to children and stepchildren. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1131–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertrich V (2017). Trends in age at marriage and the onset of fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 43(S1), 112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, & Timberlake JM (2014). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1214–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JA (2017). The timing of marriage vis-à-vis coresidence and childbearing in Europe and the United States. Demographic Research, 36, 609–626. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y (2016). Impact of rural-to-urban migration on family and gender values in China. Asian Population Studies, 12, 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn MC, & Birenbaum-Carmeli D (2008). Assisted reproductive technologies and Culture change. Annual Review of Anthropology, 37, 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks JA, Morgan SP, Bachrach CA, & Kohler HP (2011) Understanding family change and variation: Toward a theory of conjunctural action. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW (2005). The “flight from marriage” in South-East and East Asia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW (2007). Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review, 33, 453–478. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW, Hull TH, & Mohamad M (2011). Changing marriage patterns in Southeast Asia: Economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Menlo Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW, & Yeung W-JJ (2014). Marriage in Asia. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1567–1583. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A (2015) Inequality begins at home: The role of parenting in the diverging destinies of rich and poor children. In Amato P, Booth A, McHale S, Van Hook J (Eds.), Families in an era of increasing inequality. National Symposium on Family Issues, 5. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M, & Konietzka D (2017). Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, causes, and consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai F (2010). Forty years of family change in Japan: A society experiencing population aging and declining fertility. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41, 581–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JC, & Raley RK (2016). Diverging patterns of union transition among cohabitors by race/ethnicity and education: Trends and marital intentions in the United States. Demography, 53, 921–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life (2nd ed.): Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R (2014). The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 18112–18115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420441111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, & Surkyn J (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14, 1–45. doi: 10.2307/1972499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe RJ (2010). The unfolding story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review, 36, 211–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg S, Pollak RA, & Stearns J (2016). Family inequality: Diverging patterns in marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30, 79–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen JB, Moslehi S, & Wang C (2018). What has driven the great fertility decline in developing countries since 1960? The Journal of Development Studies, 54, 738–757. [Google Scholar]

- Manning W, Smock PJ, & Majumdar D (2004). The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26, 427–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00427.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JW, Boli-Bennett J, & Chase-Dunn C (1975). Convergence and divergence in development. Annual Review of Sociology, 1, 223–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.01.080175.001255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CW (1959). The sociological imagination. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Minh A, Muhajarine N, Janus M, Brownell M, & Guhn M (2017). A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: How, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health & Place, 46, 155–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer M (2013). LGBT sexuality and families at the start of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman MJK, & Martin JA (2018). Timing and adequacy of prenatal care in the United States, 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports, 67, 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC, Denney JT, & Krueger PM (2011). Cross-national sources of health inequality: Education and tobacco use in the World Health Survey. Demography, 48, 653–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B (2014). How similar are cohabiting and married parents? Second conception risks by union type in the United States and across Europe. European Journal of Population, 30, 437–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesando LM, & the GFC team. (in press). Global family change: Persistent diversity with development. Population and Development Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2018). Social media use continues to rise in developing countries, but plateaus across developed ones. Retrieved from http://www.pewglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/06/Pew-Research-Center-Global-Tech-Social-Media-Use-2018.06.19.pdf

- Raymo JM, Park H, Xie Y, & Yeung WJ (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In Duncan GJ & Murnane RJ (Eds.), Whither opportunity (pp. 91–116). New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Choe MK, & Brauner-Otto SR (2016). The emergence of two distinct fertility regimes in economically advanced countries. Population Research and Policy Review, 35, 287–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland DT (2007). Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1311–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, & Heggeness M (2008). Intergenerational coresidence in developing countries. Population and Development Review, 34, 253–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, & Miller AJ (2011). Class differences in cohabitation processes. Family Relations, 60, 163–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D, Hastings OP, & LaBriola J (2018). Income inequality and class divides in parental investments. American Sociological Review, 83, 475–507. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, & Han H (2014). The reversal of the gender gap in education and trends in marital dissolution. American Sociological Review, 79, 605–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA (2004). Cohabitation in the United States and Britain: Demography, kinship, and the future. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA, Bachrach CA, Bianchi SM, Bledsoe CH, Casper LM, Chase-Lansdale P. Thomas D (2005). Explaining family change and variation: Challenges for family demographers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 908–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter E (1977). The making of the modern family. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Smeeding T (2006). Poor people in comparative perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, & Wolfers J (2007). Marriage and divorce: Changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stone L (1977). The family, sex and marriage in England 1500–1800. New York: Harper & Row [Google Scholar]

- Surkyn J, & Lesthaeghe R (2004). Value orientations and the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, 3(3), 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, & Chatters L (2018). Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 30, 229–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therborn G (2004). Between sex and power: Family in the world, 1900–2000. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E (2014). Family complexity in Europe. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A (2001) The developmental paradigm, reading history sideways, and family change, Demography, November 2001, 38, 4, 449–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, & Young-DeMarco L (2004). Four decades of trends in attitudes towards family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1009–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, & Philipov D (2009). Sweeping changes in marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing in Central and Eastern Europe: New insights from the developmental idealism framework. European Journal of Population, 25, 123–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Pierotti RA, Young-DeMarco L, & Watkins S (2014). Developmental idealism and cultural models of the family in Malawi. Population Research and Policy Review, 33, 693–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Lillard LA, & Panis CWA (2002). Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of Education, Marriage, and Fertility. Demography, 39, 311–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kaa DJ (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. New York: Population Reference Bureau. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC (1990). From local to national communities: The transformation of demographic regimes in Western Europe, 1870–1960. Population and Development Review, 16, 241–272. doi: 10.2307/1971590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Baehr P, & Wells GC (2002). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism and other writings. Location?: Penguin Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C (2001). On the scale of global demographic convergence 1950–2000. Population and Development Review, 27, 155–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C (2011). Understanding global demographic convergence since 1950. Population and Development Review, 37, 375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, & Sonnenschein S (2016). Family contexts of academic socialization: The role of culture, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Research in Human Development, 13, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yount KM (2009). Women’s “justification” of domestic violence in Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar]