Abstract

Background

Routine screening reduces colorectal cancer mortality, but screening rates fall below national targets and are particularly low in underserved populations.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of a single text message outreach to serial text messaging and mailed fecal home test kits on colorectal cancer screening rates.

Design

A two-armed randomized clinical trial.

Participants

An urban community health center in Philadelphia. Adults aged 50–74 who were due for colorectal cancer screening had at least one visit to the practice in the previously year, and had a cell phone number recorded.

Interventions

Participants were randomized (1:1 ratio). Individuals in the control arm were sent a simple text message reminder as per usual practice. Those in the intervention arm were sent a pre-alert text message offering the options to opt-out of receiving a mailed fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kit, followed by up to three behaviorally informed text message reminders.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was participation in colorectal cancer screening at 12 weeks. The secondary outcome was the FIT kit return rate at 12 weeks.

Key Results

Four hundred forty participants were included. The mean age was 57.4 years (SD ± 6.1). 63.4% were women, 87.7% were Black, 19.1% were uninsured, and 49.6% were Medicaid beneficiaries. At 12 weeks, there was an absolute 17.3 percentage point increase in colorectal cancer screening in the intervention arm (19.6%), compared to the control arm (2.3%, p < 0.001). There was an absolute 17.7 percentage point increase in FIT kit return in the intervention arm (19.1%) compared to the control arm (1.4%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Serial text messaging with opt-out mailed FIT kit outreach can substantially improve colorectal cancer screening rates in an underserved population.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03479645)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-020-06415-8.

KEY WORDS: colorectal cancer screening, behavioral economics, text message reminders, fecal immunochemistry test (FIT), mailed outreach

BACKGROUND

Regular participation in screening effectively reduces the risk of dying from colorectal cancer (CRC). 1,2Although 87% of Americans believe that taking part in regular cancer screening is beneficial,3 national screening rates (62–67%) fall below national targets. 4,5 CRC screening rates are often lower in medically underserved populations such as uninsured, low income, and racial and ethnic minority groups.6 These populations are also more likely to present with more advanced disease.7

Insights from behavioral economics might help overcome some of the barriers and biases that limit screening. 8–11 For example, present bias reflects our tendency to place more weight on the present day costs of being screened—the effort, monetary cost, and potential discomfort—than on the potentially larger longer-term benefits, such as avoiding cancer or detecting it early.12 Similarly, status quo bias reflects our tendency to retain our current path, which means people who previously did not participate in screening are likely to continue to not take part.10,13,14 We also tend to be overly optimistic—systematically underestimating the chances of personally encountering an adverse event in the future.15,16 But specific tools such as providing something of value upfront for free, often can result in acts of reciprocity. 17,18 CRC screening programs which use outreach techniques that acknowledge, and perhaps harness these biases and tools, might increase screening rates.

For example, in the USA, CRC screening participation often relies upon opportunistic and sometimes haphazard recommendation and referral by a patient’s primary care provider (PCP) at a clinic appointment that was booked for a different clinical reason. Mailed home fecal immunochemistry test (FIT) kits have been shown to significantly improve screening participation 11,19. A number of reasons might explain this: by bypassing the structural barrier of a face-to-face clinical encounter otherwise required, thereby reducing the practitioner’s burden of remembering to endorse screening or the patient’s burden of acquiring a test kit, or by leveraging reciprocity (e.g., a free mailed FIT kits may encourage kit completion out of a sense of wanting to reciprocate). Offering the default option of opting-out of receiving a mailed FIT kit instead of opting-in, or a pre-alert delivery by letter, also increases completion of screening tests.10,20,21 However, the source of the request to be screened also impacts participation; screening requests from a patient’s PCP rather than their local health authority improves screening rates. 22–25 Rates might also increase by making information more salient. 26–28

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends evidence-based communication channels such as letters, telephone, or email reminders to improve cancer screening rates. 29,30 Although effective,31 these approaches can be costly.32 In contrast, text message reminders, also known as short message services (SMS), are low cost, easy to scale,33 and are delivered instantaneously. Two studies conducted in Israel and the USA using SMS reminders to increase CRC screening showed an increase of 1.8 percentage points compared to no SMS 34 and 3.3 percentage points compared to routine care of mailed and phone reminders.35 A larger study conducted in the UK found an increase only among first time invitees.36 Nonetheless, SMS reminders have proven a promising communication channel in other cancer screening programs. 33,37

OBJECTIVE

We combined both themes: motivational messages delivered through SMS communication channels paired with a behavioral economics-informed opt-out design for mailed FIT screening. The objective was to compare this approach to usual care in a pragmatic clinical trial in a racial and ethnically diverse, underserved population.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study Design

This two-arm, parallel, randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared multiple SMS alerts and an “invitation to screen” letter with mailed FIT kits to the current routine care of a simple SMS alert. Approval was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived as the study posed no more than minimal risk to participants and could not be practicably carried out without the waiver.38 The protocol was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03479645).

Participants

This study was conducted in a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Philadelphia, which serves a population composed largely of racial and ethnic minority groups, Medicaid beneficiaries, and uninsured patients. We included adults between 50 and 74 years old, with at least one visit to the practice in the past year and a cellular phone number recorded in the electronic health record (EHR), who were overdue for screening—defined as not having stool testing in the previous year, flexible sigmoidoscopy in the previous 5 years, or a colonoscopy in the past 10 years.

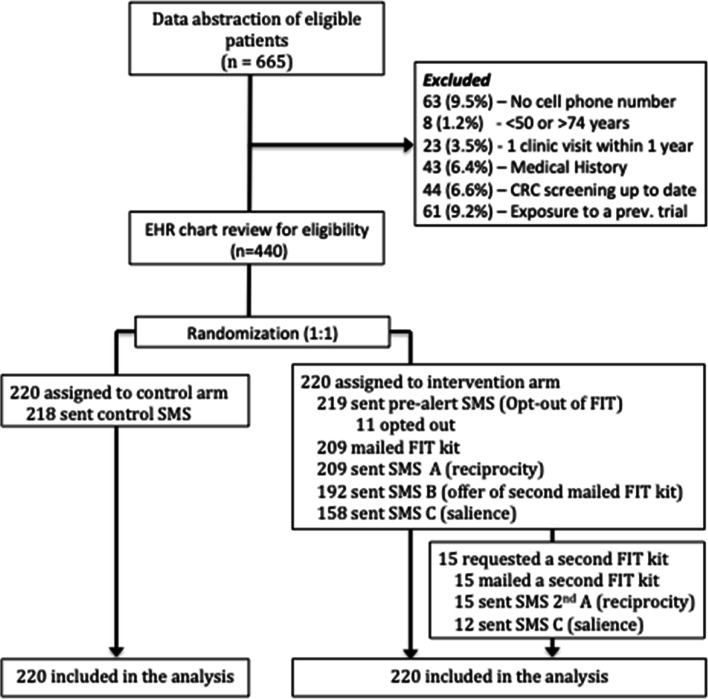

Patients were excluded if they had a history of gastrointestinal cancer, metastatic cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, other forms of colitis, or a genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer, since FIT may not be the appropriate screening test. We also excluded those with a history of colectomy, end-stage renal disease, dementia, or cirrhosis since they may not benefit from screening (Fig. 1). Potential participants were identified in January 2018 from the EHR and eligibility was confirmed with manual chart review.

Figure 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram of this randomized clinical trial. This figure describes the study design, including recruitment, exclusions, randomization, and the intervention arm procedure. CRC, colorectal cancer screening; SMS, short text service/text message; FIT, fecal immunochemistry test.

Interventions

Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into two arms using a computerized random number generator by the research team (SH, CR). Participants, care providers, and those assessing the trial outcomes were blinded to trial arm allocation. Patients in the control arm received the standard care text message reminder informing the patient that they were overdue for colorectal screening, which asked them to make contact with the clinic to discuss screening options, as per the clinic’s routine practice (Appendix 1).

Patients in the intervention arm received a sequence of communications shown, individually to improve behavior in screening and other domains. The initial communication received by the intervention group was a “pre-alert” SMS, which was clearly labeled as coming from the primary care provider clinic and informed the participant they were overdue for screening. The pre-alert SMS also delivered an emotive message implicitly endorsing CRC screening: “We care about your health” and offered participants the option to opt-out of receiving a free mailed FIT home test kit. Individuals were then given 1 week to opt-out, after which non-responders were mailed the kit. The mailed FIT kit contained a headed letter from the health clinic which addressed the recipient by name and endorse CRC screening by explaining the need for the test, and highlighting in bold key salient messages about the test, for example: the test is free, quick and easy to complete at home, and could save his or her life (Appendix 2). The letter also contained a “Why Get Screened?” section which illustrated key statistics of the frequency of colon cancer to mitigate potential optimism bias.

The kit included a specimen tube and laboratory requisition form, both pre-labeled with each patient’s name and related information to make completing the test as personalized and easy as possible.

The mailed kit was followed by up to three text messages if the FIT kit was not returned, each labeled as coming from the primary care clinic, sent at 2-week intervals. The first reminder SMS re-iterated a reciprocity message. The second offered patients to opt-in to receive a second mailed FIT kit in the event of loss or not receiving the first kit. This message was included because a previous study suggested that many non-participants contacted after the trial reported not receiving the initial FIT kit and requested a second.39 The final reminder SMS provided a salience message on the ease and privacy of completing the test in the patient’s home. Participants who requested a second mailed FIT kit were sent the first (reciprocity) and final (salience) SMS reminder at 2-week intervals if the second kit was not returned. SMS services were provided by medical mobile technology platform (CareMessage).40

Participants could also respond in free text to the research team, or reply “STOP” at any time if they wished to unsubscribe from any further text message reminders. Each SMS in the intervention arm also contained a phone number, which was answered by the research team, to respond to any questions participants might have.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was completion of CRC screening (colonoscopy or FIT) within 12 weeks of the initial outreach. The secondary outcome was completion of FIT screening within 12 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Accepting a two-sided p value of < 0.05 as statistically significant, the study was designed with 80% power to detect an absolute 8% difference in response rates between both trial arms, through an anticipated enrolment of 460 patients. All randomized patients were included in the intent-to-treat analysis using a chi-squared test. Analyses were performed using STATA version 13.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas).

KEY RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Six hundred sixty-five patients were identified through automated EHR extraction as potentially eligible to participate. After chart review, 440 were included and randomized to two trial arms (Fig. 1). The mean age was 57.4 years (SD ± 6.1). 63.4% were women, 87.7% were Black, 96.1% spoke English as their first language, 19.1% were uninsured, 49.6% were primarily Medicaid beneficiaries, 16.8% received primarily Medicare, and 14.6% were privately insured. Patient demographics and insurance characteristics by trial arm are presented in Table 1. Two patients in the control arm and one patient in the intervention arm were not exposed to the treatment, as they had either completed CRC screening between the data extraction and the first text message being deployed (two patients), or because they died since the data extraction (one patient). They were however included in the data analysis. Both trial arm interventions were deployed from March 2018 to May 2018, and outcome data were collected after 12 weeks.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Demographic and Insurance Characteristics by Trial Arm

| Control (n = 220) | Intervention (n = 220) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 57.7 (± 6.7) | 57.1 (± 5.5) |

| Female (%) | 137 (62.3) | 142 (64.5) |

| Race (%) | ||

| White—non-Hispanic | 11 (5.0) | 9 (4.9) |

| White—Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Black | 198 (90) | 188 (85.5) |

| Other | 11 (5.0) | 21 (9.5) |

| First Language (%) | ||

| English | 208 (94.5) | 215 (97.7) |

| Primary insurance type (%) | ||

| Private | 33 (15.0) | 31 (14.1) |

| Medicare | 43 (19.6) | 31 (14.1) |

| Medicaid | 104 (47.3) | 114 (51.8) |

| Uninsured | 40 (18.2) | 44 (20.0) |

Intervention Deployment and Response to Outreach

SMS was sent to 218 participants in the control arm. In response, two participants unsubscribed from SMS reminders (Table 2). In the intervention arm, the pre-alert SMS was sent to 219 participants. In response, two participants opted out of receiving a mailed home test kit, four requested no further text messages, three participants self-reported being up to date with CRC screening, and one reported an incorrect phone number. FIT kits were mailed to 209 participants (95%) in the intervention arm. One week later, all 209 patients were sent SMS A (reciprocity). After a further 2 weeks, 192 non-responders were sent SMS B (opt-in for second FIT kit). After a further 2 weeks, 158 non-responders were sent SMS C (salience). In response to SMS B, 15 participants requested and were mailed a second FIT kit.

Table 2.

Responses to SMS and Colorectal Screening Completion Rate by Trial Arm at 12 Weeks

| Control (n = 220) | Intervention (n = 220) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response to text message (%) | |||

| Unsubscribed to text messages | 2 (0.9) | 9 (4.1) | - |

| Wrong number reported | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Replied to opt-out of mailed FIT | - | 2 (0.9) | - |

| Self-reported colon screening as up to date | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.8) | - |

| FIT kit mailed (%) | - | 209 (95) | - |

| Second FIT kit requested and mailed (%) | - | 15 (6.7) | - |

| FIT kit returned after second mailing | - | 5 (2.3) | - |

| Colorectal screening completed (%) | 5 (2.3) | 43 (19.6) | < 0.001 |

| FIT | 3 (1.4) | 42 (19.1) | < 0.001 |

| Colonoscopy | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.8) | 0.41 |

FIT, fecal immunochemical test

Overall, nine participants in the intervention arm unsubscribed from SMS reminders by 12 weeks compared to two in the control arm.

Colorectal Screening Completion

All 440 randomized patients were included in the data analysis. At 12 weeks, participants in the control arm had a CRC screening rate (FIT or colonoscopy) of 2.3% (n = 5) compared to 19.6% (n = 43) in the intervention arm, an absolute difference of 17.3 percentage points (X2 (1) = 33.76; p < 0.001). Based on the absolute difference in completion rate, the number needed to intervene (NNI) to achieve one additional CRC screening is 5.7 additional patients receiving the multimodal intervention. There was no difference in uptake by sex, age, racial/ethnic group, or insurance status.

The FIT kit return rate was 17.7 percentage points higher in the intervention arm at 19.1% (n = 42) compared to the return rate in the control arm, 1.4% (n = 3), (X2 (1) = 37.651; p < 0.001). In the intervention arm, four kits were returned by participants who received a second FIT kit. No difference was seen in the rate of colonoscopy between the control arm 0.9% (n = 2) and in the intervention arm 1.8% (n = 4), (X2 (1) = 0.676; p = 0.411).

Intervention Costs

The total cost of the intervention to the FQHC was low at $151.32; the text message platform already in use at the FQHC does not charge for additional text messages sent out. The FIT kits were provided for free by the lab for uninsured patients or reimbursed by insurance companies or Medicaid. The kits and the intervention letter were mailed inside a standard A9-sized envelope (i.e., half the size of a normal sheet of print paper) ($0.10/envelope) using a standard first class postage stamp ($0.55/envelope). Additional address and test sample labels cost $0.03 per mailed FIT kit. There were 38 additional participants screened in the intervention arm, resulting in a cost of $4.01 per every additional participant screened.

No harms were observed.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the impact of a multimodal intervention using a behaviorally informed intervention design on colorectal cancer screening rates in an urban, racially and ethnically diverse, and underserved population. Our intervention resulted in a higher colorectal screening rate compared to the standard practice in a traditionally difficult to reach population. A series of SMS offering opt-out mailed home test kits were a feasible and effective alternative to the current practice of single SMS reminders.

Previous research has shown the effectiveness of a number of individual tools used in this intervention design, including pre-alert communications,20,21,41,42 opt-out defaults,43 SMS reminders,34–36 mailed fecal home test kits,11,19 and the importance of message content within screening communications.22–24 This study assesses their impact when combined in a multimodal intervention for CRC screening and the observed success likely reflects a collection of mechanisms working alone or together.

The intervention may have logistical appeal for health programs. First, providing mailed FIT kits for home use based on population level eligibility reduces health system burden—potentially supplanting the need for appointments to discuss and refer for screening. Second, this kind of automation replaces individual clinicians’ need to opportunistically recognize and refer patients overdue for screening who are presenting with other primary clinical complaints. Third, by providing mailed test kits to anyone due for screening without relying on face-to-face clinical encounters, the intervention also reaches individuals who would otherwise not have made contact with the clinic. Finally, text messaging was a low cost option for ongoing engagement with patients, and it may be a preferred communication option for underserved populations.

The design of this trial has strengths. (1) The intervention achieved a large increase in CRC screening participation in a population with historically low screening rates: by targeting an underserved population served by a FQHC; (2) the trial was pragmatic: using existing and in-use communication channels, the trial caused minimal disruption to staff; (3) using current usual care as the control arm, it allowed a direct comparison to current practice and how this could be improved; (4) because consent was waived, it was not limited to those more motivated individuals who consent for trials, but instead applied to an unselected population, more likely to represent those who would be subject to the intervention outside of the trial.38 (5) The intervention was provided at no cost to participants and clearly identified as such, thereby mitigating a potential financial barrier. The FQHC also agreed support participants requiring further investigations (e.g., with colonoscopy), to find emergency Medicaid coverage, where their health insurance status might leave them out of pocket.

This study has several limitations. First, due to its pragmatic, combined intervention design, it is not possible to assess the effect of each individual element of the intervention design on CRC screening participation. Previous trials testing individual elements have shown different effect sizes. For example, a previous study found a 19.5 percentage points increase in participation in individuals offered to opt-out (29.1% opt-out) compared to those offered to opt-in (9.6%).10 However, this study was conducted in a large health system serving an affluent population in which less than 10% were either uninsured or Medicaid insured.

Second, our follow-up period covered only 12 weeks post intervention. However, 2 months of additional EHR review identified only two further colonoscopies and one further FIT test completed, suggesting that most participants responded within the first 3 months. Third, SMS-based interventions rely on the clinic holding high levels of accurate mobile phone numbers, and policies that do not require separate consent for text messaging interventions. In this trial, only 9.5% of participants were excluded due to a lack of mobile phone number recorded on the EHR.

CONCLUSION

Systematic outreach for colorectal cancer screening using SMS pre-alerts and reminders with behaviorally informed content and opt-out mailed FIT kits can substantially improve effective screening in an underserved primary care population. A cancer screening strategy cannot rely solely on the availability of effective cancer screening tests; this also requires effective patient engagement. While we cannot identify which individual elements of this intervention design work, every element is within reach of most health care programs and could be provided at low cost, creating the possibility of implementation at scale.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 142 kb)

Acknowledgments

The clinical care and IT team at the Family Planning and Counseling Network, where this trial was completed, were integral in the successful completion this RCT.

Funding

Dr. Huf’s time is supported by the Commonwealth Fund through the Harkness Fellowship. Dr. Volpp’s time is supported by the NIA P30 Penn Roybal Center on Behavioral Economics and Health. Dr. Mehta’s time is supported by grant number K08CA234326 from the National Cancer Institute.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Huf has nothing to disclose; Dr. Asch reports other from Principle at the behavioral consulting firm VAL, outside the submitted work; Dr. Volpp reports grants from National Institute on Aging P30 Penn Roybal Center on Behavioral Economics and Health, personal fees from Consulting income CVS Caremark, other from Research funding CVS Caremark, other from Research funding Humana, other from Research funding Discovery (South Africa), other from Research funding Hawaii Medical Services Association, other from Research funding Oscar, other from Research funding Weight Watchers, other from Principle at behavioral economics consulting firm VAL Health, outside the submitted work; Ms. Reitz has nothing to disclose; Dr. Mehta reports grants from K08CA234326 from the National Cancer Institute, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1541–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC.gov. Use of Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests by State www.cdc.gov/cancer: Center for Disease Control; 2016 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/research/articles/use-colorectal-screening-tests-state.htm.

- 5.Healthypeople.gov. Colorectal Cancer Screening (C-16) healthypeople.gov2018 [Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Clinical-Preventive-Services/data.

- 6.Guessous I, Dash C, Lapin P, Doroshenk M, Smith RA, Klabunde CN, et al. Colorectal cancer screening barriers and facilitators in older persons. Prev Med. 2010;50(1-2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, Schrag NM, Bian J, Chen AY. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):222–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta SJ, Asch DA. How to help gastroenterology patients help themselves: leveraging insights from behavioral economics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):711–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta SJ, Khan T, Guerra C, Reitz C, McAuliffe T, Volpp KG, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Opt-in Versus Opt-Out Colorectal Cancer Screening Outreach. Am J Gastroenterol 2018.10.1038/s41395-018-0151-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Giorgi Rossi P, Grazzini G, Anti M, Baiocchi D, Barca A, Bellardini P, et al. Direct mailing of faecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized population study from Central Italy. J Med Screen. 2011;18(3):121–7. doi: 10.1258/jms.2011.011009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahneman DTA. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):263–92. doi: 10.2307/1914185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuelson W, Zeckhauser R. Status quo bias in decision making. J Risk Uncertain. 1988;1:7–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00055564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutter DR. Attendance and reattendance for breast cancer screening: A prospective 3-year test of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br J Health Psychol 2000;5(1).10.1348/135910700168720

- 15.Sharot T. The Optimism Bias: Why We’re Wired to Look on the Bright Side: Constable & Robinson; 2012.

- 16.Weinstein ND, Marcus SE, Moser RP. Smokers’ unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tob Control. 2005;14(1):55–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cialdini RB. Influence : the psychology of persuasion. Rev. ed. New York: Collins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehr EG, Simon Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity. J Econ Perspect. 2000;14(3):159–81. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.3.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tinmouth J, Patel J, Austin PC, Baxter NN, Brouwers MC, Earle C, et al. Increasing participation in colorectal cancer screening: results from a cluster randomized trial of directly mailed gFOBT kits to previous nonresponders. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(6):E697–703. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole SR, Smith A, Wilson C, Turnbull D, Esterman A, Young GP. An advance notification letter increases participation in colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen. 2007;14(2):73–5. doi: 10.1258/096914107781261927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Libby G, Bray J, Champion J, Brownlee LA, Birrell J, Gorman DR, et al. Pre-notification increases uptake of colorectal cancer screening in all demographic groups: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Screen. 2011;18(1):24–9. doi: 10.1258/jms.2011.011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewitson P, Ward AM, Heneghan C, Halloran SP, Mant D. Primary care endorsement letter and a patient leaflet to improve participation in colorectal cancer screening: results of a factorial randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(4):475–80. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole SR, Young GP, Byrne D, Guy JR, Morcom J. Participation in screening for colorectal cancer based on a faecal occult blood test is improved by endorsement by the primary care practitioner. J Med Screen. 2002;9(4):147–52. doi: 10.1136/jms.9.4.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zajac IT, Whibley AH, Cole SR, Byrne D, Guy J, Morcom J, et al. Endorsement by the primary care practitioner consistently improves participation in screening for colorectal cancer: a longitudinal analysis. J Med Screen. 2010;17(1):19–24. doi: 10.1258/jms.2010.009101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Nooijer DP, de Waart FG, van Leeuwen AW, Spijker WW. Participation in the Dutch national screening programme for uterine cervic cancer higher after invitation by a general practitioner, especially in groups with a traditional low level of attendance. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149(42):2339–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahneman DTA. Anomalies: Utility Maximization and Experienced Utility. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(1):221–34. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul Dolan DDH, King D, Vlaev I, Hallsworth M MINDSPACE Influencing behaviour through public policy. 2010.

- 28.Acera A, Manresa JM, Rodriguez D, Rodriguez A, Bonet JM, Sanchez N, et al. Analysis of three strategies to increase screening coverage for cervical cancer in the general population of women aged 60 to 70 years: the CRICERVA study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:86. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.USPTF. The Community Guide, What works to promote health. Cancer Prevention and Control: Client-Oriented Interventions to Increase Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening 2016 [Available from: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/cancer/screening/client-oriented/index.html.

- 30.Prevention CfDCa. Increasing Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Action Guide for Working with Health Systems. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services;; 2013 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/crccp/pdf/colorectalactionguide.pdf.

- 31.Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Balsley K, Ranalli L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1235–41. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duffy SW, Myles JP, Maroni R, Mohammad A. Rapid review of evaluation of interventions to improve participation in cancer screening services. J Med Screen 2016.10.1177/0969141316664757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Uy C, Lopez J, Trinh-Shevrin C, Kwon SC, Sherman SE, Liang PS. Text Messaging Interventions on Cancer Screening Rates: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e296. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagoel L, Neter E, Stein N, Rennert G. Harnessing the Question-Behavior Effect to Enhance Colorectal Cancer Screening in an mHealth Experiment. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):1998–2004. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller CJ, Robinson RF, Smith JJ, Jernigan MA, Hiratsuka V, Dillard DA, et al. Text message reminders increased colorectal cancer screening in a randomized trial with Alaska Native and American Indian people. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1382–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirst Y, Skrobanski H, Kerrison RS, Kobayashi LC, Counsell N, Djedovic N, et al. Text-message Reminders in Colorectal Cancer Screening (TRICCS): a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(11):1408–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huf S, Kerrison RS, King D, Chadborn T, Richmond A, Cunningham D, et al. Behavioral economics informed message content in text message reminders to improve cervical screening participation: Two pragmatic randomized controlled trials. Prev Med. 2020;139:106170. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asch DA, Ziolek TA, Mehta SJ. Misdirections in Informed Consent - Impediments to Health Care Innovation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1412–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1707991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta SJ, Oyalowo A, Reitz C, Dean O, McAuliffe T, Asch DA, et al. Text messaging and lottery incentive to improve colorectal cancer screening outreach at a community health center: A randomized controlled trial. Prev Med Rep. 2020;19:101114. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.www.caremessage.org. CareMessage [Available from: www.caremessage.org.

- 41.Senore C, Ederle A, DePretis G, Magnani C, Canuti D, Deandrea S, et al. Invitation strategies for colorectal cancer screening programmes: The impact of an advance notification letter. Prev Med. 2015;73:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zajac IT, Duncan AC, Flight I, Wittert GA, Cole SR, Young GP, et al. Theory-based modifications of an advanced notification letter improves screening for bowel cancer in men: A randomised controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2016;165:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1340–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 142 kb)