INTRODUCTION

In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPTF) recommended universal screening for depression in all adult patients in the primary care setting.1 However, depression screening rates of primary care patients remain low,2 likely due to physicians’ reliance on clinical intuition rather than validated screening tools to inform their treatment decisions for depression.3 A promising non-financial strategy to change physician behavior has been the use of social comparison feedback via report cards.4 Our objective was to determine whether or not physician peer comparison report cards would increase depression screening rates in a general internal medicine clinic.

METHODS

This was a prospective observational study to evaluate the effect of monthly, emailed physician report cards on depression screening rates at the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) academic internal medicine clinic. There were a total of 34 attending (65% female) and 70 resident (60% female) primary care physicians (PCPs) involved in the study. We excluded PCPs involved in the design of the study (including N. L.) and PCPs who did not see patients at least one month before or any time after the initiation of the report card use. We designed a health maintenance activity (HMA) in the EHR (Epic) for annual depression screening. A passive best practice advisory (BPA) was indicated if a patient was due for screening and included a link to a smart flowsheet for the Patient Health Questionnaire-2/9 (PHQ-2/9).5 If the patient scored ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9, then the BPA would prompt PCPs to click on a SmartSet that included orders for psychiatry referral, common diagnoses, and patient education materials.

In February 2016, we turned on the HMA and BPA for annual depression screening in the PCG. Between February 2016 and June 2016 (phase 1), we observed the baseline screening rate. Because the rate remained low, between July 2016 and October 2016 (phase 2), we emailed attending PCPs a monthly report card (see Online Supplement) that included each physician’s depression screening rate in rank order for the current month alongside data from the two months prior. The depression screening report cards were not distributed to resident PCPs. Between November 2016 and January 2017 (phase 3), no monthly reports were sent due to limited information technology services during a hospital-wide EHR upgrade. The monthly reports resumed from February 2017 until July 2017 (phase 4).

Data Analysis

We used the difference in difference (DID) method to compare PCP-level monthly screening rates between attending and resident PCPs to examine the effect of the report cards, where resident PCPs were the natural control group. We used a segmented mixed model with random time change points via a linear mixed model6 to assess the effect of report card use.

RESULTS

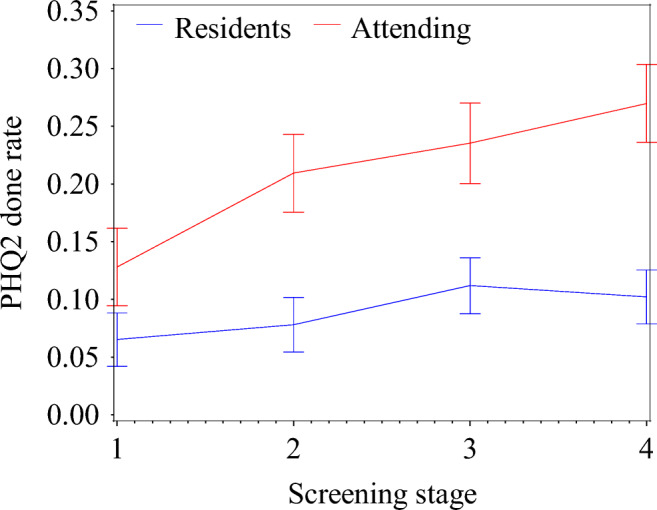

During the study period, the overall screening rate increased from 8.7 to 17.0% (Table 1). The attending PCP screening rate increased from 12.8% at phase 1 to 27.0% at phase 4 (p < 0.001), and resident PCP screening rate increased from 6.5% at phase 1 to 10.2% at phase 4 (p = 0.032) (Fig. 1). Before the dissemination of report cards (phase 1), there was no significant difference in screening rate between attending and resident PCPs (p = 0.13). After the report card intervention began (phases 2–4), the depression screening rate by attending PCPs was higher than resident PCPs at each phase (all p < 0.004). Although attending physicians did not receive report cards during phase 3, there was a carryover effect from phase 2 (p = 0.33). The DID between attending and resident PCPs was 7.8% (95% CI, 2.9%, 12.6%; p = 0.0018) after averaging phases 2 to 4.

Table 1.

Depression Screening Rates for Residents and Attending Physicians Over Time

| Time periods | Overall clinic screening rate: % screened (SD) by raw data | Residents screening rate: % screened (SE) by LMM | Attending physicians screening rate: % screened (SE) by LMM | % Screening difference between residents and attending physicians (SE) by LMM | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 8.7 (18.4) | 6.5 (2.3) | 12.8 (3.4) | 6.3 (4.1) | 0.1296 |

| Phase 2 | 12.7 (23.8) | 7.8 (2.4) | 21.0 (3.4) | 13.1 (4.2) | 0.0018 |

| Phase 3 | 15.7 (25.5) | 11.2 (23.5) | 23.5 (3.5) | 12.3 (4.3) | 0.0042 |

| Phase 4 | 17.0 (27.2) | 10.2 (2.3) | 27.0 (3.4) | 16.8 (4.1) | < 0.0001 |

Phase 1: No report cards (February–June 2016); Phase 2: Monthly report cards begin for attending physicians (July–October 2016); Phase 3: Report cards halted (November 2016–January 2017); Phase 4: Monthly report cards resumed (February–July 2017); LMM, linear mixed model; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error

Figure 1.

Depression screening rates with standard error bars for residents and attending physicians over time.

DISCUSSION

Due to the low uptake of depression screening in the primary care setting, our study attempted to use peer comparison report cards to increase screening by PCPs. In this study, we found that peer comparison report cards boosted screening rates significantly. However, even with this intervention, rates of depression screening among attending PCPs remained low (< 30%). Therefore, other strategies (e.g., screening by other clinical personnel or using electronic tools) should be considered.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 176 kb)

Funding Information

This work was supported by an Innovation Grant from the University of Chicago Medicine’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akincigil A, Matthews EB. National Rates and Patterns of Depression Screening in Primary Care: Results From 2012 and 2013. PS. 2017;68(7):660–666. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs CH, Haradhvala N, Hubley S, et al. Physician actions following a positive PHQ-2: implications for the implementation of depression screening in family medicine practice. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33(1):18–27. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348–353. doi: 10.1370/afm.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muggeo VM, Atkins DC, Gallop RJ, Dimidjian S. Segmented mixed models with random changepoints: a maximum likelihood approach with application to treatment for depression study. Stat Model. 2014. 10.1177/1471082X13504721.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 176 kb)