Abstract

Cerebral cavernous malformations are slow-flow thrombi-containing vessels induced by two-step inactivation of the CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 gene within endothelial cells. They predispose to intracerebral bleedings and focal neurological deficits. Our understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that trigger endothelial dysfunction in cavernous malformations is still incomplete. To model both, hereditary and sporadic CCM disease, blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) with a heterozygous CCM1 germline mutation and immortalized wild-type human umbilical vein endothelial cells were subjected to CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CCM1 gene disruption. CCM1 −/− BOECs demonstrated alterations in cell morphology, actin cytoskeleton dynamics, tube formation, and expression of the transcription factors KLF2 and KLF4. Furthermore, high VWF immunoreactivity was observed in CCM1 −/− BOECs, in immortalized umbilical vein endothelial cells upon CRISPR/Cas9-induced inactivation of either CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 as well as in CCM tissue samples of familial cases. Observer-independent high-content imaging revealed a striking reduction of perinuclear Weibel-Palade bodies in unstimulated CCM1 −/− BOECs which was observed in CCM1 +/− BOECs only after stimulation with PMA or histamine. Our results demonstrate that CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is a powerful tool to model different aspects of CCM disease in vitro and that CCM1 inactivation induces high-level expression of VWF and redistribution of Weibel-Palade bodies within endothelial cells.

Keywords: cerebral cavernous malformation, CCM1, blood outgrowth endothelial cells, CRISPR/Cas9, von Willebrand factor

Introduction

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are convolutes of dilated capillaries in the central nervous system. Familial occurrence of multiple CCMs (OMIM 116860, 603284, 603285) is associated with autosomal-dominantly inherited loss-of-function variants in one of the three genes CCM1 (KRIT1, OMIM: *604214), CCM2 (Malcavernin, OSM, *607929) or CCM3 (PDCD10, TFAR15, *609118). In agreement with a Knudsonian two-hit mechanism, somatic inactivation of the corresponding wild-type allele in vascular endothelial cells (ECs) is widely accepted as the critical step in CCM initiation (Gault et al., 2005; Akers et al., 2009; Pagenstecher et al., 2009; McDonald et al., 2014; Rath et al., 2020). In patients without a pathogenic germline variant, two biallelic somatic mutations are thought to cause CCM disease (McDonald et al., 2014).

Since the first reports of disease-causing CCM1 variants in familial CCM cases (Laberge-le Couteulx et al., 1999; Sahoo et al., 1999), we have learned a lot about CCM pathogenesis and the endothelial dysfunction in cavernous lesions (Maddaluno et al., 2013; Cuttano et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016; Detter et al., 2018; Malinverno et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2021). A first expert consensus guideline and clinical recommendations for CCM management have been published in recent years (Akers et al., 2017; Flemming and Lanzino, 2020). However, there are still no effective drugs that would prevent cavernoma formation or CCM bleeding. A recent prospective population-based study revealed that antithrombotic therapy – anticoagulant as well as antiplatelet – is associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and focal neurological deficits (Zuurbier et al., 2019). These counterintuitive data are consistent with a neuropathological study that anticipated a dysfunction of cavernous ECs which would result in local organizing thrombi as the primary step causing repeated secondary microhemorrhages and disease progression (Abe et al., 2005). The multimeric von Willebrand factor (VWF) protein is an important player in primary hemostasis. VWF is almost exclusively expressed by vascular ECs and bone marrow megakaryocytes (Lip and Blann, 1997). In the vascular endothelium, VWF is stored in Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs) which secrete their prothrombotic content through exocytosis (Weibel and Palade, 1964; Sadler, 1998; Wagner and Frenette, 2008). Secretion of large amounts of VWF from WPBs can be triggered by shear stress or stimulation with Ca2+ raising agents like histamine, thrombin or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Loesberg et al., 1983; Erent et al., 2007).

Using CRISPR/Cas9-based in vitro modeling of hereditary and sporadic CCM disease, we here demonstrate that the inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in ECs induces intracellular VWF accumulation and WPB redistribution. Analyses of human CCM tissue samples support the hypothesis that increased VWF levels in the endothelium of distended caverns contribute to the local hemostatic imbalance in these fragile vascular lesions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The generation of blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) from a CCM proband with a pathogenic CCM1 germline variant (CCM1 +/−) has been described before (Spiegler et al., 2019). Immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (CI-huVECs) were obtained from InSCREENex (Braunschweig, Germany) and maintained in complete endothelial cell growth medium (ECGM; PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Tube formation was performed in 384-well microplates. In brief, 17 µl Matrigel (Corning, Kaiserslautern, Germany) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, 8,000 cells were seeded. After 16 h, tube formation was imaged and quantified with the angiogenesis analyzer for ImageJ (https://imagej.net). To stimulate secretion of WPBs, cells were grown on 96- or 6-well plates, preincubated with Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h and treated solely in Opti-MEM or with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), 150 nM Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, United States), 100 µM Histamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), 1 µM Desmopressin (Acetate) (DDAVP, MedChem Express, Sollentuna, Sweden) or 1 µM DDAVP plus 100 µM 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) in Opti-MEM for 1 h according to Wang and colleagues (Wang et al., 2013).

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing

CCM1 −/− BOECs were generated with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing from CCM1 +/− BOECs as described before (Spiegler et al., 2019). In brief, CCM1 +/− BOECs were transfected with crRNA:tracrRNA:Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes that were specific to the CCM1 wild-type allele. Upon confluence on T25 flasks, the CRISPR/Cas9-treated cell mixture was seeded on 96-well plates with an average cell density of 0.5 cells/well. Emerging BOEC clones were genotyped by next generation sequencing in a custom two-step PCR enrichment approach. PCR products were pooled after purification with Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States) and sequenced with 2 × 150 cycles on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, California, United States of America). The SeqNext software was used for data analysis (JSI Medical Systems, Ettenheim, Germany). Only variants with quality scores ≥30 were called. BOEC clones with biallelic CCM1 loss-of-function variants (CCM1 −/−) were selected for further expansion. Three to four individual CCM1 +/− BOEC lines that had been clonally expanded from the blood of the CCM proband were used as controls. For complete knockout of CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3 in CI-huVECs, the following Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNAs (Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Coralville, Iowa, United States of America) were used: 5′-GGAGCTCCTAGACCAAAGTA-3′ (CCM1), 5′-GGTCAGTTAACGTCCATACC-3' (CCM2), and 5′-CAACTCACCTCATTAAACAC-3' (CCM3). A non-targeting crRNA (nc crRNA #1, IDT) served as control. Reverse transfection, estimation of the genome editing efficiencies by T7 endonuclease I digestion or Sanger sequencing, and the expansion of knockout CI-huVEC clones were performed as delineated previously (Schwefel et al., 2019; Spiegler et al., 2019; Schwefel et al., 2020).

Immunofluorescence Analyses

After fixation of the cells on 96-well plates with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilization, and several washing steps, immunofluorescent analyses were performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-human KLF4 (1:100, PA5-27441, Thermo Fisher Scientific), rabbit anti-vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin (1:100, ab33168, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), CytoPainter Phalloidin-iFluor 488 (1:1,000, ab176753, Abcam), mouse anti-human KLF2 (1:88, MAB5466, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America), monoclonal mouse anti-human vWF (1:100, MA5-14029, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (A-11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (ab150114, Abcam) or Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (A-21429, Thermo Fisher Scientific). DAPI (D9542, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to stain cell nuclei and image acquisition was performed with either an EVOS FL (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or a Zeiss LSM980 Airyscan 2 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) after addition of mounting medium (50001, Ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany). After the sensitivity and specificity of VWF staining had been verified, the focus was placed on the CCM1 −/− cells in direct comparisons to avoid overexposure.

High-Content Imaging

Quantification of WPBs was performed on cells grown on glass bottom imaging plates (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and following secretagogues treatment using a high-content imaging microscope (Operetta CLS; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, United States). In addition to the digital phase contrast channel (pseudo-cytosolic signal), the images were acquired in three z-planes to detect VWF-positive granula (λex 475 nm/λem 500–550 nm) and DAPI-stained nuclei (λex 365 nm/λem 430–500 nm). The algorithm-driven image quantification was performed utilizing the Harmony 4.9 (Perkin Elmer) imaging and analysis software. The images were combined with their maximum projection intensities from all three z-planes and flatfield-adjusted. Per treatment and cell type, at least 2,500 cells in a total of 27 fields of view have been included in the analysis. The nuclei were segmented by their DAPI signal, followed by detection of the surrounding cytosolic area. A selection step was applied to exclude border region objects and dead cells with fragmented nuclei. In order to enhance the contrast, a sliding parabola function was applied, which allowed better discrimination of bright objects. Afterward, the number of WPBs and their intensity was determined inside the cytosolic cell region. To assess the amount of WPBs near the cell nucleus, a 5 µm ring-region was calculated and the granules were quantified inside this region.

Biochemical Analyses

To quantify the secretion of VWF, cell culture supernatants were collected and concentrated (Vacuum concentrator centrifuge, UniEquip, Planegg, Germany). Proteins were analyzed in duplicates using Human VWF-A2 DuoSet ELISA (DY2764-05, R&D Systems) and Ancillary Reagent Kit (DY008, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 450 and 540 nm was measured on a Paradigm platform (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States). Values were corrected for 540 nm and normalized to untreated cells.

Immunohistochemistry on Tissue Samples

Immunohistochemistry was performed on FFPE tissue slices as described before (Pagenstecher et al., 2009) using vWF antibody (1:100, M616, Dako (Agilent)) following heat induced antigen retrieval in citrate buffer. Staining intensity in the endothelia of CCMs and vessels in the surrounding brain was evaluated semiquantitatively using five tiers ranging from 0 to ++++.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States). Multiple t tests or two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. Where appropriate, Šidák or Dunnet corrections for multiple comparisons were used. For quantification of ELISA data, VWF concentrations were calculated from the standard curve by linear regression performed with the Origin software (Northampton, MA, United States). The standard curve was obtained by fitting the Hill equation [y=Vmax*xn/(kn+xn)] to our data, with Vmax = 6.00716, k = 8,210.36, n = 0.72, and R2 = 0.99319. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Results

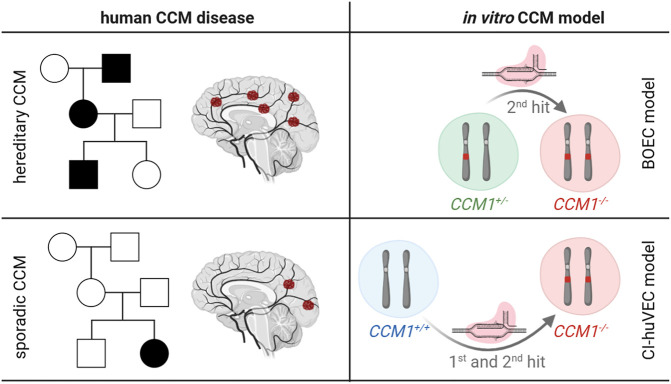

Modeling Hereditary and Sporadic CCM Disease In Vitro

To model the hereditary and sporadic type of CCM disease in vitro (Figure 1), we used BOECs isolated from peripheral blood of a CCM proband with a heterozygous CCM1 loss-of-function germline variant (CCM1 +/−) and wild-type CI-huVECs (CCM1 +/+). Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, we inactivated the CCM1 wild-type allele in CCM1 +/− BOECs or induced biallelic frameshift variants in CCM1 +/+ CI-huVECs and thereby generated pairs of CCM1 +/− and CCM1 −/− BOECs (hereditary CCM model) or CCM1 +/+ and CCM1 −/− CI-huVECs (sporadic CCM model), respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of CCM cell culture models. Features of hereditary and sporadic CCM disease (left subpanels) as well as the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing approaches that have been used in this study (right subpanels) are schematically depicted (created with BioRender.com). Filled symbols in the pedigrees indicate CCM patients. CCM1 +/+ = cells with two CCM1 wild-type alleles; CCM1 +/− = cells with a heterozygous CCM1 mutation; CCM1 −/− = cells with biallelic CCM1 mutations.

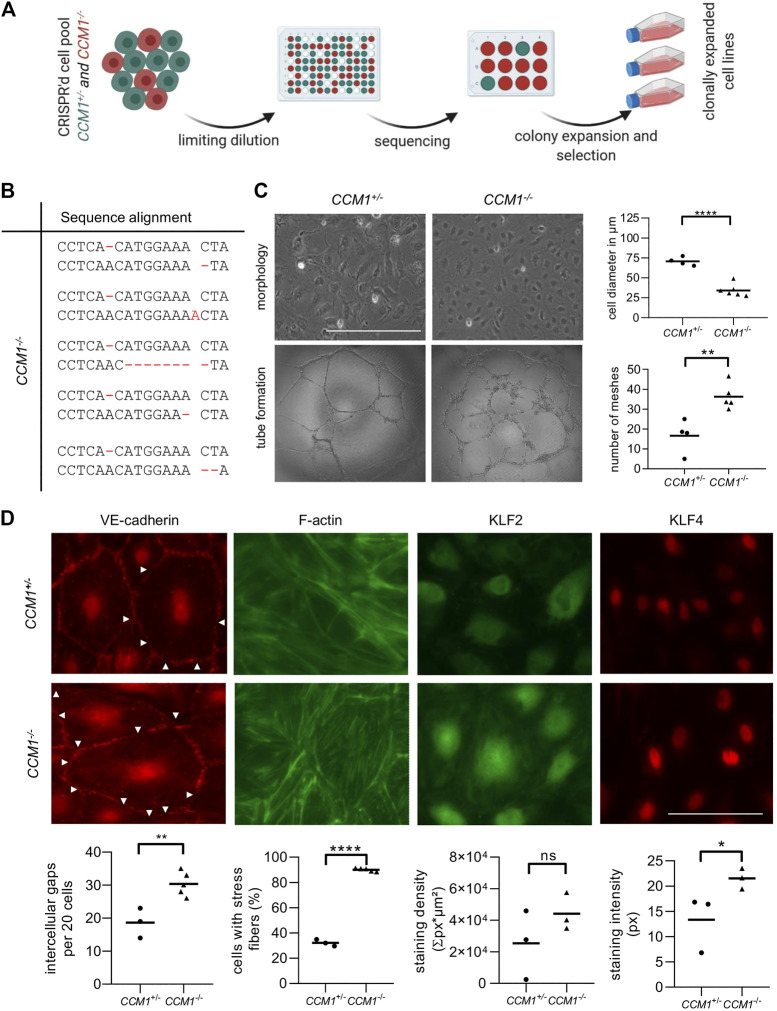

CCM1 −/− BOECs Reflect Key Features of CCM Disease

To study the effects of second-hit inactivation of CCM1 in human ECs, we first established thirty clonal CCM1 −/− BOEC lines in a single cell cloning approach (Figure 2A). NGS amplicon sequencing verified compound heterozygosity for the pre-existing CCM1 germline variant and a second CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutation that led to inactivation of the CCM1 wild-type allele (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table S1). Further cell line characterizations demonstrated striking differences between CCM1 −/− and CCM1 +/− BOECs in terms of cell morphology, angiogenic properties, integrity of intercellular junctions, and organization of the actin cytoskeleton. While CCM1 +/− BOECs had a cell diameter of 70 µm in two-dimensional monolayer culture, CCM1 −/− BOECs presented a more compact morphology with a diameter of only 34.2 µm. In addition, the number of meshes formed by CCM1 −/− BOECs on Matrigel-coated plates was significantly increased by 118% (Figure 2C). We also examined the integrity of endothelial adherens junctions as this is a main determinant of vascular permeability (Figure 2D). Remarkably, VE-cadherin staining revealed a 62,6% increase of intercellular gaps upon second-hit inactivation of CCM1 in BOECs. While stress fibers (SF) were found in only 32% of CCM1 +/− BOECs, over 90% of CCM1-deficient BOECs were SF-positive (Figure 2D). The misregulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics in CCM1 −/− BOECs further reinforced that our BOEC model reflects key features of CCM pathophysiology. Since the zinc finger transcription factors KLF2 und KLF4 have been reported as drivers of CCM disease (Renz et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016), we decided to address KLF2/4 expression in our in vitro model of hereditary CCM disease. KLF4 levels were significantly increased in CCM1 −/− BOECs (Figure 2D). Furthermore, a significant upregulation of KLF2 mRNA (Supplementary Figure S1), and a trend towards increased KLF2 expression on protein level were found in CCM1 −/− BOECs (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of CCM1 +/− and clonally expanded CCM1 −/− BOECS. (A) CCM1 −/− BOECs were established by limiting dilution of the CRISPR/Cas9 RNP-treated cell pool and clonal expansion of single cells (created with BioRender.com). (B) Shown are the genotypes of CCM1 −/− BOEC clones included in this study. All variants either lead to a frameshift or a premature stop codon (additional information on the CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations and numbers of individual clones are given in Supplementary Table S1). (C) CCM1 −/− BOECs presented a more compact morphology in brightfield microscopy and increased tube formation. The largest cell diameter and the number of meshes formed on Matrigel-coated plates were quantified. Scale bar indicates 400 µm. Data are presented as single data points with the mean (n = 4–6). (D) Immunofluorescence staining revealed a higher number of intercellular gaps (white arrowheads), more actin stress fibers, and a higher expression of KLF2 and KLF4 in CCM1 −/− BOECs. Representative images are shown. Scale bar indicates 100 µm. Individual data points are shown with the mean (n = 3–5). Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; ns = not significant; VE-cadherin = vascular endothelial cadherin.

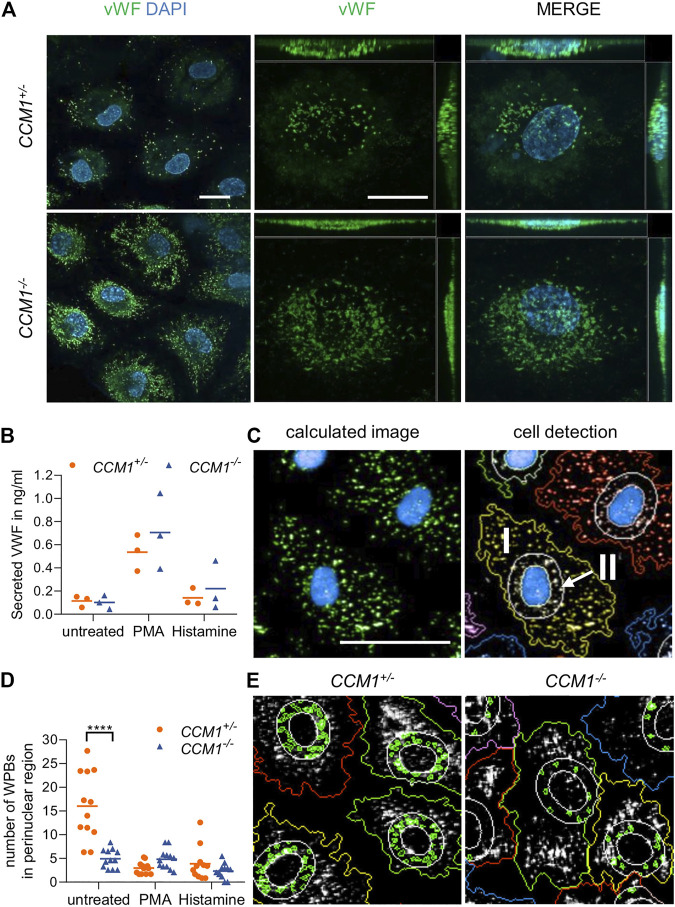

CCM1 Gene Disruption Induces High-Level VWF Expression and WPB Redistribution in BOECs

Immunofluorescence staining unexpectedly revealed a significant enrichment of the endothelial marker protein VWF in clonally expanded CCM1 −/− BOECs when compared to CCM1 +/− BOECs (Figure 3A). Targeted next generation sequencing of all coding exons and exon-intron junctions revealed no VWF variant which might affect gene expression or VWF secretion. Since the endothelium is the main source of plasma VWF (Nichols et al., 2008), we asked the question of whether VWF secretion might be impaired upon complete CCM1 inactivation in human ECs. Hence, VWF levels in cell culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA. Notably, the responsiveness of CCM1 −/− BOECs to stimulation with histamine which triggers Ca2+-mediated VWF secretion and the potent non-physiological secretagogue PMA was intact and the secreted VWF levels were not significantly different between CCM1 +/− and CCM1 −/− BOECs (Figure 3B). To determine alterations of the morphology and intracellular distribution of WPBs upon second-hit inactivation of CCM1, their length and the number of WPBs in the perinuclear region were quantified by observer-independent high-content imaging (Figure 3C). WPBs were slightly longer in CCM1 −/− BOECs (2.84 µm vs. 2.76 µm under basal conditions, p = 0.001; data not shown). Interestingly, a perinuclear accumulation of WPBs was found in unstimulated CCM1 +/− BOECs. Stimulation with histamine, PMA or the vasopressin analog DDAVP which triggers cAMP-mediated exocytosis, reduced the number of WPBs in the perinuclear region of CCM1 +/− BOECs (Figures 3D,E and Supplementary Figure S2). In unstimulated CCM1 −/− BOECs, however, WPBs did not accumulate in the perinuclear region (Figures 3D,E). Additionally, only histamine treatment, but not stimulation with either PMA or DDAVP, induced an additional translocation of WPBs and further reduced their number in the perinuclear region of CCM1 −/− BOECs (Figures 3D,E and Supplementary Figure S2).

FIGURE 3.

High VWF content and aberrant WPB distribution in CCM1 −/− BOECs. (A) Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated high-level VWF expression (green) in clonally expanded CCM1 −/− BOECs. DAPI (blue) was used as nuclear counterstain. Confocal images were acquired using a 63x (NA 1.4) oil objective (left) and at higher magnification shown as maximum intensity projection of image stacks (0.2 µm z planes). Scale bars indicate 20 µm. (B) Absolute amount of secreted VWF from CCM1 +/− and CCM1 −/− BOECs as quantified by ELISA. Data are presented as single data points with the mean (n = 3). (C) Analysis strategy of high-content imaging for untreated and stimulated BOECs. As basis for quantification, a sliding parabola function was applied for contrast enhancement of the VWF signal (green). Cell nuclei were segmented by their DAPI signal (blue) and the surrounding cytosolic area and perinuclear region were detected. VWF-positive granules in the cytosol (I) and the perinuclear region (II) were quantified. Scale bar indicates 30 µm. (D) WPBs in the perinuclear region were quantified as shown in untreated CCM1 +/− and CCM1 −/− BOECs. Data are presented as single data points with the mean. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák correction for multiple comparisons was used for statistical analysis. p < 0.05. All experiments were performed in triplicates and four biological replicates. (E) Representative images of WPBs in the perinuclear region in untreated CCM1 +/− (left) and CCM1 −/− BOECs (right).

In conclusion, the CRISPR/Cas9-induced second-hit inactivation of CCM1 had caused a VWF reduction in the perinuclear region comparable to the level seen after stimulation with secretagogues in heterozygous CCM1 +/− BOECs. These changes most likely reflect a constitutively activated state of CCM1 −/− BOECs.

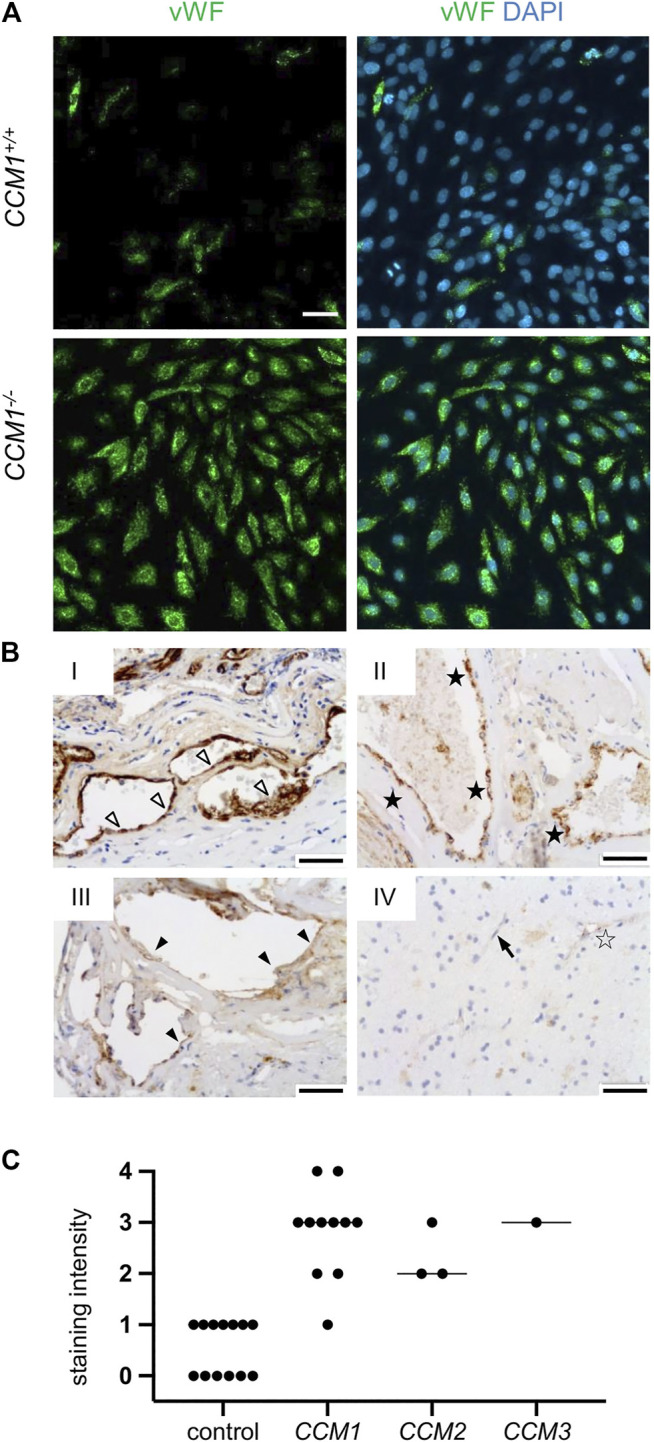

High VWF Levels in CI-huVECs after CCM1/2/3 Protein Inactivation and in the Endothelium of Human CCMs

VWF levels have recently been reported as marker for the proliferation capacity of individual BOEC clones (de Boer et al., 2020) which are also called endothelial colony forming cells (Nowak-Sliwinska et al., 2018). Furthermore, changes in VWF expression might also indicate different stages of aging and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition of BOECs in cell culture (de Jong et al., 2019; de Boer et al., 2020). In a next step, we therefore used immortalized CI-huVECs which represent a well characterized EC culture model (Heiss et al., 2015; Lipps et al., 2018). In line with our observations in CCM1 −/− BOECs, clonally expanded CCM1 −/− CI-huVECs presented strong immunopositivity for VWF (Figure 4A). The same outcome was seen in CI-huVECs that had been treated with CCM1-, CCM2- or CCM3-specific crRNA:tracrRNA:Cas9 RNPs (Supplementary figure S3).

FIGURE 4.

High-level VWF expression is a common feature of CCM disease. (A) Strong immunopositivity for VWF (shown in green) was also found in clonally expanded CCM1 −/− CI-huVECs. DAPI (blue) was used as nuclear counterstain. Confocal images were acquired using a 10x (NA 0.45) objective. Scale bar indicates 50 µm. (B) Immunohistochemistry demonstrated medium to strong VWF staining intensities (SI) in CCM tissue samples of hereditary cases (I-III). IV = normal brain. Representative images are shown. Open arrowhead = [SI] 4, black asterisk = [SI] 3, filled arrowhead = [SI] 2, open asterisk = [SI] 1, arrow = [SI] 0. Scale bars indicate 50 µm. The graph displays the staining intensity of normal brain vessels in the vicinity of CCMs (n = 13) and of cavernous vessel endothelia in CCM1 (n = 11), CCM2 (n = 3), and CCM3 (n = 1) probands. Bars indicate the median.

Finally, we validated our in vitro data in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded CCM tissue samples of fifteen probands with a pathogenic germline variant in either CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 and loss of CCM protein expression in the CCM endothelium (Pagenstecher et al., 2009). In accordance with our in vitro data, immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated high VWF signals in endothelial cells lining distended caverns (Figures 4B,C).

Discussion

Identifying a molecular explanation for the bleeding tendency of CCMs has been defined as one of the top research priorities by patients and health-care providers (Al-Shahi Salman et al., 2016). Following this recommendation, we here demonstrate the value of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in modeling hereditary and sporadic CCM disease in vitro, add VWF to the growing list of molecules involved in CCM pathogenesis, and support the hypothesis that a local hemostatic imbalance contributes to thrombosis and hemorrhage in CCMs.

Genome editing has become a powerful tool to model complex human diseases in vitro. We have previously used the CRISPR/Cas9 technology for targeted correction of the CCM1 mutant allele and second-hit inactivation of CCM1 in CCM1 +/− BOECs. However, the low clonogenicity of CCM1 +/+ BOECs and the survival advantage of CCM1 −/− BOECs hampered our efforts to fully mimic CCM lesion genesis in vitro (Spiegler et al., 2019). Hence, we have now combined our BOEC model which perfectly reproduces the two-hit inactivation mechanism of hereditary CCM (CCM1 +/− vs. CCM1 −/−) with our CI-huVEC model which mimics sporadic CCM disease (CCM1 +/+ vs. CCM1 −/−). Well-known features of CCM pathobiology such as actin stress fiber formation, disruption of the integrity of intercellular junctions or upregulation of the transcription factors KLF2 and KLF4 (Glading et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2011; Faurobert et al., 2013; Shenkar et al., 2015; Cuttano et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016) were recapitulated in this cell culture model.

Furthermore, we addressed a new aspect of the hemostatic imbalance in CCMs. CCM bleeding is one of the major concerns of CCM patients and their doctors. Since the risk of future bleeding events is even increased after a first hemorrhage (Al-Shahi Salman et al., 2012), the existence of an anticoagulant micromilieu in CCMs seems plausible (Lopez-Ramirez et al., 2019). However, the frequent observation of thrombi in caverns and nonhemorrhagic focal neurological deficits in CCM patients (Abe et al., 2005; Al-Shahi Salman et al., 2008; Cortes Vela et al., 2012; Horne et al., 2016) suggest a more complex interplay of pro- and anticoagulatory processes in CCM disease. High VWF levels in ECs upon CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 gene disruption and, most importantly, the striking VWF immunopositivity within the lining endothelium of individual caverns of human CCMs support this hypothesis. Since stimulation with secretagogues induced proper VWF secretion in CCM1 −/− BOECs, it is reasonable to assume that vascular stasis and transient procoagulant stimuli trigger local thrombus formation in cavernous lesions. The high affinity of thrombin for the anticoagulant endothelial receptor thrombomodulin which is strongly expressed on ECs of capillaries in the wall of cavernous blood vessels (Abe et al., 2005), may, on the other hand, confer limited protection against thrombosis at the cost of potential bleeding (Lopez-Ramirez et al., 2019). Loose intercellular junctions and recapillarization of organizing thrombi may further promote repeated microhemorrhages into the neighboring brain tissue.

VWF secretion and WPB distribution inside ECs are controlled by a highly regulated molecular network. The secretagogues histamine, DDAVP, and PMA used in this study cover the most important signaling cascades of WPB exocytosis from human ECs (Schillemans et al., 2019). Remarkably, stimulation of CCM1 −/− BOECs with these secretagogues demonstrated that the second-hit inactivation of CCM1 does not attenuate the regulated exocytosis of WPBs. Although we cannot exclude that other stimuli such as forskolin, epinephrine, thrombin or VEGF (Rondaij et al., 2006) might have a different effect on CCM1-deficient ECs, our observations point to increased intracellular storage of VWF upon CCM1 inactivation. Besides cAMP- or Ca2+-dependent pathways, Rab proteins that are recruited to WPB, the dynein-dynactin complex, the SNARE machinery, the transcription factor KLF2, and various other signaling pathways influence the formation and secretion of WPBs (Rondaij et al., 2006; van Agtmaal et al., 2012; Nightingale and Cutler, 2013; Mourik and Eikenboom, 2017). The observations from our present study suggest that CCM1 modulates this dynamic process in a KLF2-dependent manner. Upregulation of KLF2 is a key feature of CCM disease and was also observed in our in vitro model. Its misexpression interferes with endothelial quiescence and increases Rho as well as ADAMTS activity (Renz et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016). Lentiviral overexpression of KLF2 in BOECs has been shown to increase the number of WPBs and reduce perinuclear WPB clustering (van Agtmaal et al., 2012). Furthermore, an increase in VWF mRNA with a simultaneous decrease in ANGPT2 mRNA was described in HUVECs upon KLF2 overexpression (Dekker et al., 2006). These are observations that were also made in our CCM1 −/− BOEC model. Despite upregulation of KLF2 in CCM1 −/− BOEC, we did not observe a shortening of WPBs which would have been indicative of reduced activity of primary hemostasis (Ferraro et al., 2016; Ferraro et al., 2020). In fact, we even found slightly longer WPBs in CCM1-depleted ECs. An increased fraction of longer WPBs can be associated with a higher prothrombotic potential because they contain substantial VWF amounts (Ferraro et al., 2014; Ferraro et al., 2016). It is probably selective exocytosis of these long WPB that might be affected by CCM1 depletion. The group of Daniel Cutler recently demonstrated that the release of large WPBs requires the recruitment of an actin ring while the exocytosis of smaller WPBs does not (McCormack et al., 2020). Interestingly, reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, particularly the decrease of cortical actin filaments and the increased formation of actin stress fibers, is one of the most studied effects of CCM protein depletion in human ECs (Figure 2D); (Glading et al., 2007; Faurobert et al., 2013; Schwefel et al., 2019; Spiegler et al., 2019; Schwefel et al., 2020). Specific actin-dependent exocytosis alterations might also be an explanation why the secretion of other WPB components can be normal or even increased in CCM1-, CCM2- or CCM3-depleted ECs as these smaller molecules can also be released by kiss-and-run or actin-independent full fusion.

In conclusion, our results point to the co-existence of pro- and anticoagulatory processes in CCM which provides an explanation for the favorable outcome seen in CCM patients who got antithrombotic therapies for other reasons (Schneble et al., 2012; Zuurbier et al., 2019). Future randomized trials will have to show whether therapies addressing hemostasiological homeostasis are not only safe for CCM patients but also have a therapeutic effect on the bleeding tendency of their CCMs.

Acknowledgments

Andreas Greinacher is thanked for fruitful discussions and comments on the manuscript. Doreen Biedenweg and Heike Geißel are thanked for excellent technical assistance.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of the University Medicine Greifswald, Germany (No: BB 047/14a). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CDM, BSS, KS, and SS performed the experiments. CDM, MR, UF, and SS contributed to the intellectual conception and the design of the study. MR, UF, and SS supervised the experiments. CDM, BSS, MR, OO, and SS analyzed the data. EF and SB executed the high-throughput imaging analysis. AP performed the immunohistochemistry of tissue samples. All authors supported in data interpretation. MR, UF, and SS drafted the manuscript and all authors participated in writing.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the Research Network Molecular Medicine of the University Medicine Greifswald to SS (FVMM, Grant No FOVB-2017-03, FOVB-2018-06). MR was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG RA2876/2-2). SB received a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, 03Z22DN11).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2021.622547/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abe M., Fukudome K., Sugita Y., Oishi T., Tabuchi K., Kawano T. (2005). Thrombus and Encapsulated Hematoma in Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Acta Neuropathol. 109 (5), 503–509. 10.1007/s00401-005-0994-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers A. L., Johnson E., Steinberg G. K., Zabramski J. M., Marchuk D. A. (2009). Biallelic Somatic and Germline Mutations in Cerebral Cavernous Malformations (CCMs): Evidence for a Two-Hit Mechanism of CCM Pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 (5), 919–930. 10.1093/hmg/ddn430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers A., Al-Shahi Salman R., A. Awad I., Dahlem K., Flemming K., Hart B., et al. (2017). Synopsis of Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Consensus Recommendations Based on Systematic Literature Review by the Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory Board Clinical Experts Panel. Neurosurgery 80 (5), 665–680. 10.1093/neuros/nyx091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahi Salman R., Berg M. J., Morrison L., Awad I. A., Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory B. (2008). Hemorrhage from Cavernous Malformations of the Brain: Definition and Reporting Standards. Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory Board. Stroke 39 (12), 3222–3230. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahi Salman R., Hall J. M., Horne M. A., Moultrie F., Josephson C. B., Bhattacharya J. J., et al. (2012). Scottish Audit of Intracranial Vascular Malformations C (2012). Untreated Clinical Course of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: a Prospective, Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet Neurol. 11 (3), 217–224. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70004-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahi Salman R., Kitchen N., Thomson J., Ganesan V., Mallucci C., Radatz M. (2016). Cavernoma Priority Setting Partnership Steering G (2016). Top Ten Research Priorities for Brain and Spine Cavernous Malformations. Lancet Neurol. 15 (4), 354–355. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00039-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés Vela J. J., Concepción Aramendía L., Ballenilla Marco F., Gallego León J. I., González-Spínola San Gil J. (2012). Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Spectrum of Neuroradiological Findings. Radiología (English Edition) 54 (5), 401–409. 10.1016/j.rx.2011.09.01610.1016/j.rxeng.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttano R., Rudini N., Bravi L., Corada M., Giampietro C., Papa E., et al. (2016). KLF 4 Is a Key Determinant in the Development and Progression of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. EMBO Mol. Med. 8 (1), 6–24. 10.15252/emmm.201505433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer S., Bowman M., Notley C., Mo A., Lima P., Jong A., et al. (2020). Endothelial Characteristics in Healthy Endothelial colony Forming Cells; Generating a Robust and Valid Ex Vivo Model for Vascular Disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 18, 2721–2731. 10.1111/jth.14998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong A., Weijers E., Dirven R., Boer S., Streur J., Eikenboom J. (2019). Variability of Von Willebrand Factor‐Related Parameters in Endothelial Colony Forming Cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 17 (9), 1544–1554. 10.1111/jth.14558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker R. J., Boon R. A., Rondaij M. G., Kragt A., Volger O. L., Elderkamp Y. W., et al. (2006). KLF2 Provokes a Gene Expression Pattern that Establishes Functional Quiescent Differentiation of the Endothelium. Blood 107 (11), 4354–4363. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detter M. R., Snellings D. A., Marchuk D. A. (2018). Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Develop through Clonal Expansion of Mutant Endothelial Cells. Circ. Res. 123 (10), 1143–1151. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erent M., Meli A., Moisoi N., Babich V., Hannah M. J., Skehel P., et al. (2007). Rate, Extent and Concentration Dependence of Histamine-Evoked Weibel-Palade Body Exocytosis Determined from Individual Fusion Events in Human Endothelial Cells. J. Physiol. 583 (Pt 1), 195–212. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurobert E., Rome C., Lisowska J., Manet-Dupé S., Boulday G., Malbouyres M., et al. (2013). CCM1-ICAP-1 Complex Controls β1 Integrin-dependent Endothelial Contractility and Fibronectin Remodeling. J. Cel. Biol. 202 (3), 545–561. 10.1083/jcb.201303044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro F., Kriston-Vizi J., Metcalf D. J., Martin-Martin B., Freeman J., Burden J. J., et al. (2014). A Two-Tier Golgi-Based Control of Organelle Size Underpins the Functional Plasticity of Endothelial Cells. Dev. Cel. 29 (3), 292–304. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro F., da Silva M. L., Grimes W., Lee H. K., Ketteler R., Kriston-Vizi J., et al. (2016). Weibel-Palade Body Size Modulates the Adhesive Activity of its von Willebrand Factor Cargo in Cultured Endothelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 32473. 10.1038/srep32473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro F., Patella F., Costa J. R., Ketteler R., Kriston‐Vizi J., Cutler D. F. (2020). Modulation of Endothelial Organelle Size as an Antithrombotic Strategy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 18 (12), 3296–3308. 10.1111/jth.15084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming K. D., Lanzino G. (2020). Cerebral Cavernous Malformation: What a Practicing Clinician Should Know. Mayo Clinic Proc. 95, 2005–2020. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gault J., Shenkar R., Recksiek P., Awad I. A. (2005). Biallelic Somatic and Germ Line CCM1 Truncating Mutations in a Cerebral Cavernous Malformation Lesion. Stroke 36 (4), 872–874. 10.1161/01.STR.0000157586.20479.fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glading A., Han J., Stockton R. A., Ginsberg M. H. (2007). KRIT-1/CCM1 Is a Rap1 Effector that Regulates Endothelial Cell-Cell Junctions. J. Cel. Biol. 179 (2), 247–254. 10.1083/jcb.200705175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss M., Hellström M., Kalén M., May T., Weber H., Hecker M., et al. (2015). Endothelial Cell Spheroids as a Versatile Tool to Study Angiogenesis In Vitro . FASEB j. 29 (7), 3076–3084. 10.1096/fj.14-267633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C. C., Tang A. T., Detter M. R., Choi J. P., Wang R., Yang X., et al. (2020). Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Are Driven by ADAMTS5 Proteolysis of Versican. J. Exp. Med. 217 (10), e20200140. 10.1084/jem.20200140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne M. A., Flemming K. D., Su I.-C., Stapf C., Jeon J. P., Li D., et al. (2016). Clinical Course of Untreated Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: a Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Lancet Neurol. 15 (2), 166–173. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00303-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge-le Couteulx S., Jung H. H., Labauge P., Houtteville J.-P., Lescoat C., Cecillon M., et al. (1999). Truncating Mutations in CCM1, Encoding KRIT1, Cause Hereditary Cavernous Angiomas. Nat. Genet. 23 (2), 189–193. 10.1038/13815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip G., Blann A. (1997). Von Willebrand Factor: a Marker of Endothelial Dysfunction in Vascular Disorders? Cardiovasc. Res. 34 (2), 255–265. 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00039-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipps C., Klein F., Wahlicht T., Seiffert V., Butueva M., Zauers J., et al. (2018). Expansion of Functional Personalized Cells with Specific Transgene Combinations. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 994. 10.1038/s41467-018-03408-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesberg C., Gonsalves M. D., Zandbergen J., Willems C., van Aken W. G., Stel H. V., et al. (1983). The Effect of Calcium on the Secretion of Factor VIII-Related Antigen by Cultured Human Endothelial Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (Bba) - Mol. Cel. Res. 763 (2), 160–168. 10.1016/0167-4889(83)90039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ramirez M. A., Pham A., Girard R., Wyseure T., Hale P., Yamashita A., et al. (2019). Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Form an Anticoagulant Vascular Domain in Humans and Mice. Blood 133 (3), 193–204. 10.1182/blood-2018-06-856062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddaluno L., Rudini N., Cuttano R., Bravi L., Giampietro C., Corada M., et al. (2013). EndMT Contributes to the Onset and Progression of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Nature 498 (7455), 492–496. 10.1038/nature12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinverno M., Maderna C., Abu Taha A., Corada M., Orsenigo F., Valentino M., et al. (2019). Endothelial Cell Clonal Expansion in the Development of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 2761. 10.1038/s41467-019-10707-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. J., Harrison‐Lavoie K. J., Cutler D. F. (2020). Human Endothelial Cells Size‐select Their Secretory Granules for Exocytosis to Modulate Their Functional Output. J. Thromb. Haemost. 18 (1), 243–254. 10.1111/jth.14634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D. A., Shi C., Shenkar R., Gallione C. J., Akers A. L., Li S., et al. (2014). Lesions from Patients with Sporadic Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Harbor Somatic Mutations in the CCM Genes: Evidence for a Common Biochemical Pathway for CCM Pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23 (16), 4357–4370. 10.1093/hmg/ddu153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourik M., Eikenboom J. (2017). Lifecycle of Weibel-Palade Bodies. Hamostaseologie 37 (1), 13–24. 10.5482/HAMO-16-07-0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols W. L., Hultin M. B., James A. H., Manco-Johnson M. J., Montgomery R. R., Ortel T. L., et al. (2008). Von Willebrand Disease (VWD): Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Management Guidelines, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Expert Panel Report (USA). Haemophilia 14 (2), 171–232. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale T., Cutler D. (2013). The Secretion of von Willebrand Factor from Endothelial Cells; an Increasingly Complicated Story. J. Thromb. Haemost. 11 Suppl. 1 (Suppl 1), 192–201. 10.1111/jth.12225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Sliwinska P., Alitalo K., Allen E., Anisimov A., Aplin A. C., Auerbach R., et al. (2018). Consensus Guidelines for the Use and Interpretation of Angiogenesis Assays. Angiogenesis 21 (3), 425–532. 10.1007/s10456-018-9613-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagenstecher A., Stahl S., Sure U., Felbor U. (2009). A Two-Hit Mechanism Causes Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Complete Inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in Affected Endothelial Cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 (5), 911–918. 10.1093/hmg/ddn420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath M., Pagenstecher A., Hoischen A., Felbor U. (2020). Postzygotic Mosaicism in Cerebral Cavernous Malformation. J. Med. Genet. 57 (3), 212–216. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren A. A., Snellings D. A., Su Y. S., Hong C. C., Castro M., Tang A. T., et al. (2021). PIK3CA and CCM Mutations Fuel Cavernomas through a Cancer-like Mechanism. Nature 594, 271–276. 10.1038/s41586-021-03562-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz M., Otten C., Faurobert E., Rudolph F., Zhu Y., Boulday G., et al. (2015). Regulation of β1 Integrin-Klf2-Mediated Angiogenesis by CCM Proteins. Dev. Cel. 32 (2), 181–190. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondaij M. G., Bierings R., Kragt A., Gijzen K. A., Sellink E., van Mourik J. A., et al. (2006). Dynein-dynactin Complex Mediates Protein Kinase A-dependent Clustering of Weibel-Palade Bodies in Endothelial Cells. Atvb 26 (1), 49–55. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000191639.08082.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler J. E. (1998). Biochemistry and Genetics of Von Willebrand Factor. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 395–424. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo T., Johnson E. W., Thomas J. W., Kuehl P. M., Jones T. L., Dokken C. G., et al. (1999). Mutations in the Gene Encoding KRIT1, a Krev-1/rap1a Binding Protein, Cause Cerebral Cavernous Malformations (CCM1). Hum. Mol. Genet. 8 (12), 2325–2333. 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillemans M., Karampini E., Kat M., Bierings R. (2019). Exocytosis of Weibel-Palade Bodies: How to Unpack a Vascular Emergency Kit. J. Thromb. Haemost. 17 (1), 6–18. 10.1111/jth.14322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneble H.-M., Soumare A., Hervé D., Bresson D., Guichard J.-P., Riant F., et al. (2012). Antithrombotic Therapy and Bleeding Risk in a Prospective Cohort Study of Patients with Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Stroke 43 (12), 3196–3199. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.668533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H., Errede M., Ulrich N. H., Virgintino D., Frei K., Bertalanffy H. (2011). Impairment of Tight Junctions and Glucose Transport in Endothelial Cells of Human Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 70 (6), 417–429. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31821bc40e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwefel K., Spiegler S., Ameling S., Much C. D., Pilz R. A., Otto O., et al. (2019). Biallelic CCM3 Mutations Cause a Clonogenic Survival Advantage and Endothelial Cell Stiffening. J. Cel. Mol. Med. 23 (3), 1771–1783. 10.1111/jcmm.14075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwefel K., Spiegler S., Kirchmaier B. C., Dellweg P. K. E., Much C. D., Pané‐Farré J., et al. (2020). Fibronectin Rescues Aberrant Phenotype of Endothelial Cells Lacking Either CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3. FASEB j. 34, 9018–9033. 10.1096/fj.201902888R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenkar R., Shi C., Rebeiz T., Stockton R. A., McDonald D. A., Mikati A. G., et al. (2015). Exceptional Aggressiveness of Cerebral Cavernous Malformation Disease Associated with PDCD10 Mutations. Genet. Med. 17 (3), 188–196. 10.1038/gim.2014.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegler S., Rath M., Much C. D., Sendtner B. S., Felbor U. (2019). Precise CCM1 Gene Correction and Inactivation in Patient‐derived Endothelial Cells: Modeling Knudson's Two‐hit Hypothesis In Vitro . Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7 (7), e00755. 10.1002/mgg3.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Agtmaal E. L., Bierings R., Dragt B. S., Leyen T. A., Fernandez-Borja M., Horrevoets A. J. G., et al. (2012). The Shear Stress-Induced Transcription Factor KLF2 Affects Dynamics and Angiopoietin-2 Content of Weibel-Palade Bodies. PLoS One 7 (6), e38399. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D. D., Frenette P. S. (2008). The Vessel wall and its Interactions. Blood 111 (11), 5271–5281. 10.1182/blood-2008-01-078204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-W., Bouwens E. A. M., Pintao M. C., Voorberg J., Safdar H., Valentijn K. M., et al. (2013). Analysis of the Storage and Secretion of Von Willebrand Factor in Blood outgrowth Endothelial Cells Derived from Patients With von Willebrand Disease. Blood 121 (14), 2762–2772. 10.1182/blood-2012-06-434373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel E. R., Palade G. E. (1964). New Cytoplasmic Components in Arterial Endothelia. J. Cel. Biol. 23, 101–112. 10.1083/jcb.23.1.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Tang A. T., Wong W.-Y., Bamezai S., Goddard L. M., Shenkar R., et al. (2016). Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Arise from Endothelial Gain of MEKK3-Klf2/4 Signalling. Nature 532 (7597), 122–126. 10.1038/nature17178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier S. M., Hickman C. R., Tolias C. S., Rinkel L. A., Leyrer R., Flemming K. D., et al. (2019). Scottish Audit of Intracranial Vascular Malformations Steering C (2019). Long-Term Antithrombotic Therapy and Risk of Intracranial Haemorrhage from Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: a Population-Based Cohort Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Neurol. 18 (10), 935–941. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30231-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.