Severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus (pH1N1) infection causes significant morbidity and mortality. We and other groups have reported that immunopathological damage induced by excessive pulmonary inflammation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of severe pneumonia and provides novel strategies for the treatment of severe influenza infection [1–3]. The complement system plays critical roles in both innate and adaptive immunity by activating the classical, alternative and lectin pathways [4]. As soluble pattern recognition lectin molecules, ficolins are enriched in the lungs and are essential for protecting the host from invading pathogens [5]. In our previous report, low-dose lipopolysaccharide (LPS) inoculation simulated bacterial infection-induced mild pneumonia without death in mice. We found that intranasal LPS administration induced local pulmonary inflammation and increased the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils and the expression of ficolin A and ficolin B. LPS-challenged ficolin A-knockout (Fcna−/−) mice showed more severe lung injury than LPS-challenged wild-type (WT) mice. These results suggest that the protective effect of ficolin A may be associated with complement activation, as well as the neutralization of LPS [6]. However, complement is a double-edged sword. Complement activation also triggers potent detrimental hyperinflammatory responses that cause tissue damage and organ failure when these responses are dysregulated or overactivated [7]. Therefore, whether ficolins play protective or detrimental roles in severe pH1N1 infection and their mechanisms need to be investigated. Our results demonstrated that ficolin A-mediated excessive complement activation exacerbates pulmonary proinflammatory responses and contributes to lung immunopathological injury. Targeting ficolin A may be a potential adjunctive therapeutic strategy for alleviating severe influenza-induced viral pneumonia.

To explore the dynamic changes of ficolins during pH1N1 infection-induced severe pneumonia, we initially measured the mRNA and protein levels of ficolins in the lung. Severe infection significantly increased the transcription of ficolin A at 3, 5 and 7 dpi and ficolin B at 1 dpi (Fig. S1a). Moreover, severe infection also gradually increased the expression of ficolin A and significantly increased ficolin B at 3 dpi (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, ficolin A was mainly expressed in neutrophils (Fig. S1b), while ficolin B was expressed in neutrophils, alveolar macrophages, interstitial macrophages and inflammatory monocytes (Fig. S1c). Similar results were also confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. S1d).

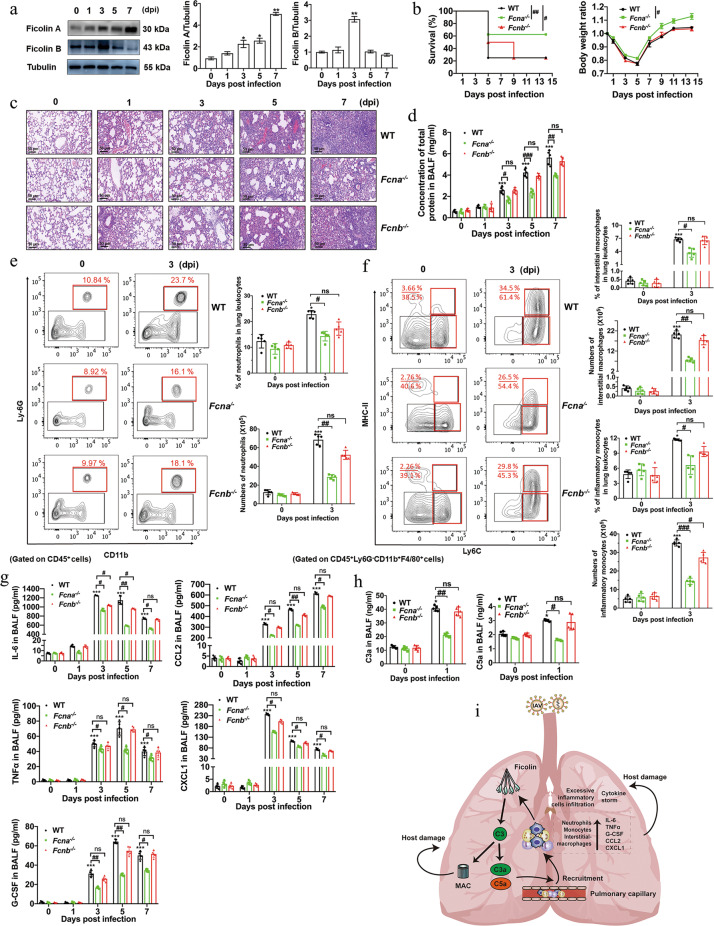

Fig. 1.

Ficolin A exacerbates pH1N1-induced acute lung injury and the overall dysregulation of inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine secretion by mediating complement activation. a Western blot analysis of ficolin A and ficolin B expression in the lungs after pH1N1 infection. b Survival rates and body weight change ratios in Fcna−/−, Fcnb−/−, and WT mice after pH1N1 infection (n = 8 in each group). c Representative lung tissue injury was assessed by H&E staining at the indicated dpi. (Original magnification: ×200, scale bar: 50 μm). d Concentrations of total protein in the BALF of Fcna−/−, Fcnb−/−, and WT mice. e Analysis of the percentages of neutrophils among lung leukocytes and the numbers of neutrophils in the lungs of Fcna−/−, Fcnb−/−, and WT mice. f Analysis of the percentages of interstitial macrophages/inflammatory monocytes among lung leukocytes and the numbers of interstitial macrophages/inflammatory monocytes in the lungs. g The histogram shows the concentrations of IL-6, TNFα, G-CSF, CCL2, and CXCL1 in the BALF of WT, Fcna−/− and Fcnb−/− mice. h The concentrations of complement C3a and C5a in BALF were measured by ELISA. i Graphic summary of the mechanisms underlying ficolin-mediated lung immunopathological damage during pH1N1 infection. The data are representative of two independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5 mice/group in each experiment). *, ** and *** represent p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively, compared with the 0 dpi (uninfected) group. #, ## and ### represent p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. ns = not significant

Fcna−/− and Ficolin B-knockout (Fcnb−/−) mice were further used to assess the roles of these genes in pH1N1-induced severe pneumonia. Notably, compared with WT and Fcnb−/− mice, Fcna−/− mice showed significant improvements in survival rates (62.5% in Fcna−/− mice vs 25% in WT and Fcnb−/− mice), less weight loss and faster weight recovery (Fig. 1b). Moreover, lung histopathological injury [the total protein concentration in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung bronchial and parenchymal destruction, including hemorrhage, alveolar edema, alveolar fusion, and bronchiolar epithelial sloughing] was significantly ameliorated, and inflammatory cell infiltration was attenuated in Fcna−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 1c,d and S2a). These results suggested that ficolin A but not ficolin B could exacerbate pH1N1-induced lung injury and decrease the survival rate.

Direct destruction of infected cells by viruses or overactivated immune systems are related to lung histopathological injury. We found that Fcna−/− and Fcnb−/− mice showed similar levels of viral replication by immunohistochemical or Western blot analysis of hemagglutinin protein in the lung (Fig. S2b–d). These results suggested that the detrimental effects of ficolin A were independent of viral replication.

The stimulation of excessive inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine storms are also critical pathogeneses [8, 9]. After severe pH1N1 infection in WT mice, alveolar macrophages were progressively decreased, and a large number of neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes and pulmonary interstitial macrophages were rapidly recruited to the lung, peaking at 3 dpi (Fig. S3a). However, severe pH1N1-infected Fcna−/− mice but not Fcnb−/− mice showed significantly decreased percentages and numbers of neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes and interstitial macrophages compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 1e,f). Moreover, the proportions and numbers of alveolar macrophages in Fcna−/− mice were similar to those in WT and Fcnb−/− mice (Fig. S3b). We also examined whether the amelioration of lung injury in Fcna−/− mice was associated with the alleviation of cytokine storms. Severe pH1N1 infection in WT mice induced the release of large amounts of cytokines and chemokines, including TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IFNγ, G-CSF, CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL1 (Fig. S3c). Compared with those of WT and Fcnb−/− mice, the concentrations of TNFα, IL-6, CCL2, CXCL1, and G-CSF in the BALF of Fcna−/− mice were markedly suppressed at 3, 5, and 7 dpi (Fig. 1g). These results suggested that ficolin A but not ficolin B exacerbated lung injury and mortality by enhancing inflammatory cell recruitment and proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine release during severe pH1N1 infection.

Ficolins can activate the complement lectin pathway to produce the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a [5]. We observed increased levels of C3a and C5a in BALF. However, compared with those of WT mice, the concentrations of C3a and C5a were significantly decreased in Fcna−/− but not Fcnb−/− mice (Fig. 1h). These results demonstrated that ficolin A-mediated complement activation was involved in severe infection-induced lung immunopathological damage.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that pulmonary myeloid-derived ficolin A may be linked to proinflammatory mediators, which contribute to complement activation and boost the inflammatory response in severe pH1N1 infection-induced acute lung immunopathological injury (Fig. 1i). Preventing the stimulation of dysregulated host innate immune response may abrogate the immunopathological damage caused by severe influenza infection.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071747, 81373114), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation, China (7182013).

Author contributions

XW, LB, ZH, DY, FL, HL and XX performed the experiments; YA and XW verified the experimental procedure and data; XW, BC, and XZ analyzed the data and wrote the paper; BC and XZ designed and supervised the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Xu Wu, Linlin Bao.

Contributor Information

Bin Cao, Email: caobin_ben@163.com.

Xulong Zhang, Email: zhxlwl@ccmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-021-00737-1.

References

- 1.Cao B, Li XW, Mao Y, Wang J, Lu HZ, Chen YS, et al. Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2507–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia X, Liu B, Bao L, Lv Q, Li F, Li H, et al. Delayed oseltamivir plus sirolimus treatment attenuates H1N1 virus-induced severe lung injury correlated with repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammatory cell infiltration. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007428. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Q, Zhou YH, Yang ZQ. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:3–10. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis ES, Mastellos DC, Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. New insights into the immune functions of complement. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:503–16. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swierzko AS, Cedzynski M. The influence of the lectin pathway of complement activation on infections of the respiratory system. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585243. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.585243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu X, Yao D, Bao L, Liu D, Xu X, An Y, et al. Ficolin A derived from local macrophages and neutrophils protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by activating complement. Immunol Cell Biol. 2020;98:595–606. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garred P, Tenner AJ, Mollnes TE, Levy FO. Therapeutic targeting of the complement system: From rare diseases to pandemics. Pharm Rev. 2021;73:792–827. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.120.000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flerlage, T, Boyd, DF, Meliopoulos, V, Thomas, PG & Schultz-Cherry, S. Influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2: pathogenesis and host responses in the respiratory tract. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021. 10.1038/s41579-021-00542-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Guo XJ, Thomas PG. New fronts emerge in the influenza cytokine storm. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:541–50. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0636-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.