Abstract

We describe a 54-year-old male in whom eosinophilic myocarditis secondary to T-cell lymphoma complicated by bilateral ischemic stroke was diagnosed. The source, identified as an apical tear with thrombus formation, was revealed by transthoracic echocardiography. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Key Words: echocardiography, eosinophilic myocarditis, thrombus

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CT, computed tomography; EM, eosinophilic myocarditis; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; LV, left ventricle; STIR, short -T1 inversion recovery

Graphical abstract

Presentation

A 54-year-old man initially presented to the hospital with pre-syncope, which progressed to syncope lasting <5 min. This was coupled with symptoms of sudden onset and left-sided chest tightness which self-resolved after 2 min. He had been under review by his general practitioner for 4 months due to generalized fatigue and weight loss.

Learning Objectives

-

•

An apical tear following eosinophilic myocarditis is a rare but significant complication with devastating consequences.

-

•

Readily available transthoracic echocardiography allows prompt diagnosis of complications.

Physical examination revealed a weight of 41 kg, a blood pressure of 96/60 mm Hg, and unremarkable cardiac and respiratory examinations. There was a diffuse erythematous rash in the left lower limb. Electrocardiography demonstrated normal sinus rhythm. Biochemistry tests revealed a raised troponin concentration of 1,268 ng/l (reference, 0 to 14 ng/l) and an eosinophil count of 7.6 × 109/l (reference 0 to 0.5 × 109 cells/l). He was referred to cardiology.

On review at the cardiac center, believed the diagnosis was myocarditis. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging showed appearances consistent with a diagnosis of eosinophilic myocarditis (EM). Coronary angiography revealed no evidence of coronary artery disease.

Given the working diagnosis of EM, secondary causes were sought. The decision was made to perform a skin biopsy, and a cardiac biopsy was considered. The patient improved clinically and was discharged with prescriptions for edoxaban, 30 mg once daily, and prednisolone, 40 mg once daily, and scheduled for follow-up in the rheumatology clinic in 2 weeks. Unfortunately, he missed that appointment and presented to cardiology clinic 2 months later with neck swelling, when he was urgently admitted to hospital. Biochemistry tests revealed a rise in his eosinophil count to 19.7 × 109 cells/l (reference, 0 to 0.5 × 109 cells/l), and it was decided to increase the dose of prednisolone to 100 mg once daily. Computed tomography (CT) of his neck demonstrated lymphadenopathy, which was promptly confirmed as T-cell lymphoma on biopsy. The decision was for a course of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide.

During this admission, the patient deteriorated from sepsis secondary to cholecystitis and later experienced new onset of seizures with a reduction in his consciousness using a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 9/15. Head CT demonstrated multiple bilateral acute infarctions. The infarct areas were not amenable to thrombectomy. The GCS score continued to deteriorate, and he was transferred to the intensive care unit. Investigations were undertaken to identify the source for the bilateral cerebral infarcts.

Medical history

He had a history of hepatitis B, asthma, intravenous drug use, and excessive use of alcohol.

Differential diagnosis

The most probable diagnosis in this case was ischemic stroke secondary to EM, given its ability to develop left ventricular (LV) thrombus and neurological complications (1). Further differential diagnoses included reduced GCS score, seizures and intracranial bleeding, and malignancy or intracerebral infection.

Investigations

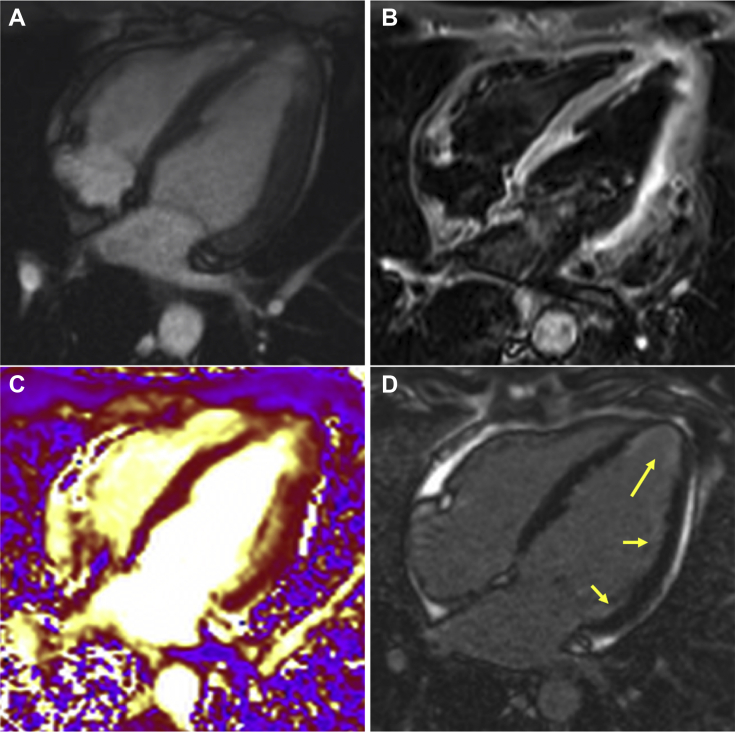

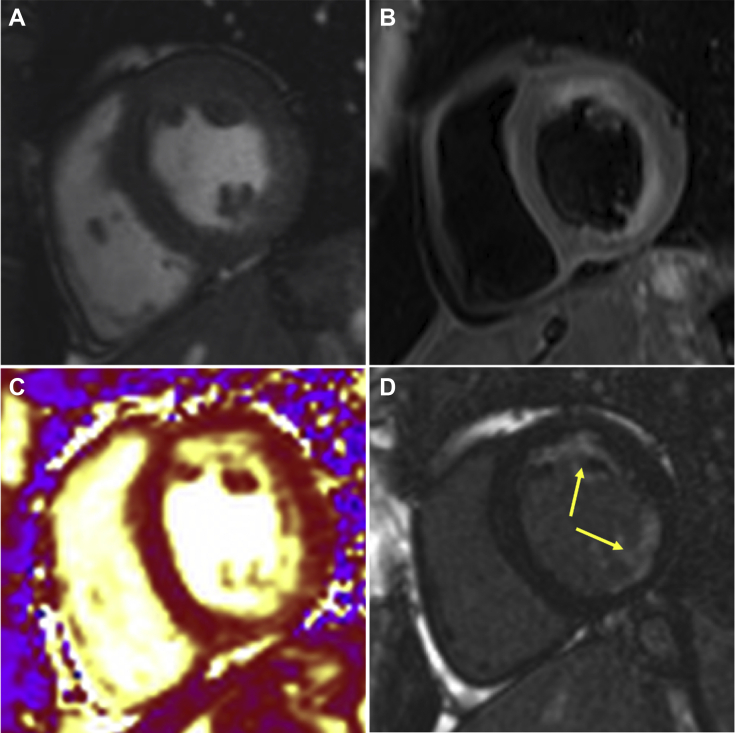

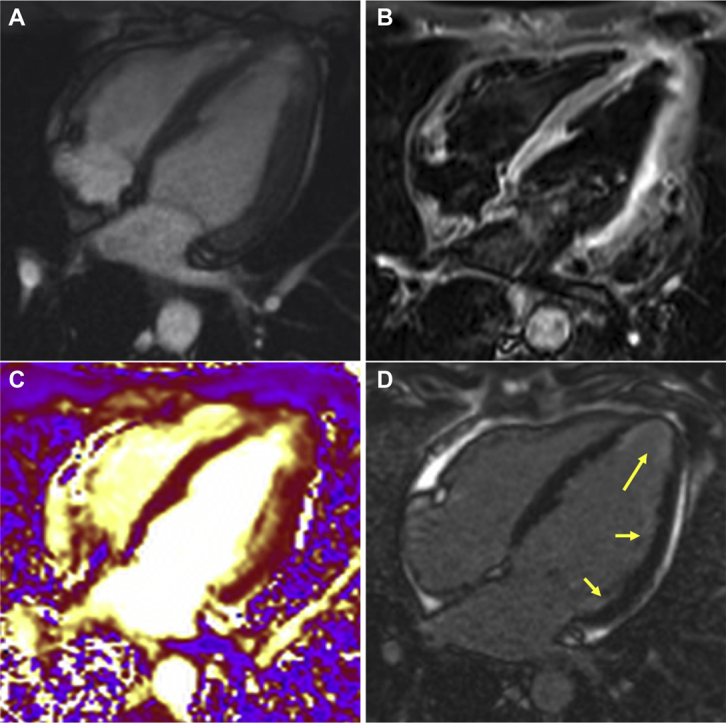

CMR demonstrated diffuse subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement matching increased signal on short-T1 inversion recovery (STIR) images, with mild LV systolic impairment (ejection fraction, 50%) (Figures 1 and 2). A skin biopsy revealed eczematous changes. A bone marrow biopsy revealed no increase in eosinophils. An axillary lymph node biopsy confirmed T-cell lymphoma. Following the reduced consciousness and seizures, head CT revealed infarcts involving the frontal, parietal, and left temporo-occipital regions.

Figure 1.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance 4-Chamber View

(A) Four-chamber steady state free precession sequence. (B) Corresponding T2-weighted STIR sequence shows increased signal in the apical and lateral segments. (C) T2-weighted map sequence demonstrates edema in the apical and lateral segments. (D) Late gadolinium-enhanced sequence shows subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement in the apical and lateral segments (yellow arrows).

Figure 2.

Short-Axis View

(A) Mid left ventricular short-axis steady state free precession sequence. (B) Corresponding T2-weighted STIR sequence shows increased signal in the anterior to inferior segments. (C) T2-weighted map sequence demonstrates edema in the anterior to inferior segments. (D) Late gadolinium-enhanced sequence shows interrupted subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement predominantly in the anterior and inferolateral segments (yellow arrows).

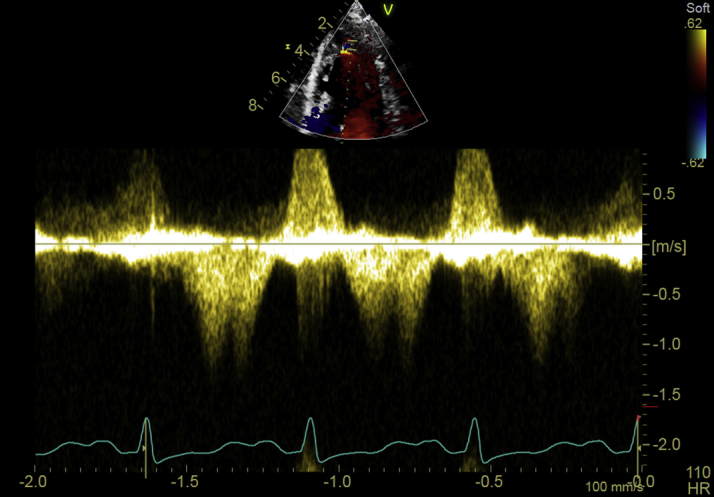

Critical care echocardiography demonstrated an apical tear with preserved apical architecture suggestive of intramural myocardial tear resulting in a small apical cavity in continuity with the main LV cavity (Video 1A). Small mobile structures were attached to dissected myocardium and believed to be the source of embolism (Video 1B). Color flow Doppler interrogation revealed diastolic flow in the apical cavity (Video 1C). Pulse wave Doppler demonstrated diastolic flow into the apical cavity and systolic flow out of it (Figure 3). A differential diagnosis based on the images would have been a cardiac thrombus alone. However, the systolic flow and evidence of disruption of the muscular layer favored an LV tear.

Figure 3.

Pulse Wave Doppler Demonstrates Diastolic Flow Into the Apical Cavity and Systolic Flow Out of It

Management

Cyclophosphamide therapy was begun, which resulted in a partial response, with a reduction of the eosinophil count to a range of 20 to 30 × 109 cells/l from 70 × 109 cells/l (reference, 0 to 0.5 × 109 cells/l).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other published reports that describe secondary EM due to T-cell lymphoma resulting in LV apical intramural tear. There have been documented cases of T-cell lymphoma causing ventricular wall rupture, but those were due to the tumor itself (2,3). Although it was not possible to perform a cardiac biopsy, given his deterioration, his clinical presentation in addition to his biochemistry markers and CMR favored a diagnosis of EM. A possible explanation for the tear could be related to activated eosinophils and eosinophil granule proteins in the necrotic and thrombotic tissue, leading to muscle damage (4).

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is hypereosinophilia with evidence of organ damage or dysfunction related solely to hypereosinophilia and not secondary to another condition. HES can be primary, secondary, or idiopathic (5). This patient’s presentation was consistent with secondary HES due to the overproduction of eosinophilopoietic factors by malignancy.

Cardiac complications of HES occur in 3 stages: an acute necrotic stage, a thrombotic stage, and a fibrotic stage (5). EM presents in stage 1 with chest pain, mimicking an acute myocardial infarction possibly related to myocardial necrosis (6). Typically the electrocardiogram would demonstrate ST-segment changes of ischemia, which were absent in this case (1). The patient experienced an embolic brain event (stage two) prior to detection of the intracardiac thrombus.

Advances in echocardiography have yielded a higher level of sensitivity of 93% for cardiac masses (7). It remains a challenge to differentiate between EM with endomyocardial thickening and apical mural thrombus based on echocardiography alone (8). The increasing number of intensive care clinicians partaking in echocardiography has been shown to help therapeutic management (9). For cardiac masses, CMR yields a respective sensitivity and specificity of 67% and 91%. EM is typically characterized as extensive myocardial hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging along with subendocardial late enhancement (10). Endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of EM with a sensitivity of 54% (1). Unfortunately, this patient deteriorated, and it was not appropriate to perform a biopsy.

EM has been successfully treated, in the medical literature, with corticosteroids with partial or complete response in 85% with monotherapy (10). The present patient was treated with both anticoagulation pre-emptively and with corticosteroids, and despite these treatments, the condition progressed.

Outcome

Following a multidisciplinary team meeting, it was decided, given his deterioration and poor prognosis, palliation was appropriate.

Conclusions

LV wall tear is a rare complication of EM. EM is difficult to treat due to its indolent course, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis. In this case, the complication was found by noncardiology specialists performing transthoracic echocardiography.

Author Relationship With Industry

This paper was funded by Barts Guild. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.

References

- 1.Kassem K.M., Souka A., Harris D.M., Parajuli S., Cook J.L. Eosinophilic myocarditis: classic presentation of elusive disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e009487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong E.J., Bhave P., Wong D. Left ventricular rupture due to HIV-associated T-cell lymphoma. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37:457–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molajo A.O., McWilliam L., Ward C., Rahman A. Cardiac lymphoma: an unusual case of myocardial perforation—clinical, echocardiographic, haemodynamic and pathological features. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:549–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tai P.-C., Spry C.F., Olsen E.J., Ackerman S., Dunnette S., Gleich G. Deposits of eosinophil granule proteins in cardiac tissues of patients with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Lancet. 1987;329:643–647. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankad R., Bonnichsen C., Mankad S. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: cardiac diagnosis and management. Heart. 2016;102:100–106. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thambidorai S.K., Korlakunta H.L., Arouni A.J., Hunter W.J., Holmberg M.J. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis mimicking myocardial infarction. Texas Heart Inst J. 2009;36:355–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkpatrick J.N., Wong T., Bednarz J.E. Differential diagnosis of cardiac masses using contrast echocardiographic perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1412–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh T.W., Coghlan J.G., Davarashvilli J., Lipkin D.P. Biventricular thrombus mimicking eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Eur Heart J. 1996;1770–1 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaulieu Y. Specific skill set and goals of focused echocardiography for critical care clinicians. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(Suppl):S144–S149. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260682.62472.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizkallah J., Desautels A., Malik A. Eosinophilic myocarditis: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:538. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.

(A) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity with small masses attached to myocardium. (B) Modified apical view demonstrates apical cavity continuation of left ventricular cavity. (C) Color flow Doppler demonstrates diastolic flow into the apical cavity.