Abstract

Objective: Transient receptor potential (TRP) melastatin 7 (TRPM7) cation channel, a dual-function ion channel/protein kinase, regulates vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) Mg2+ homeostasis and mitogenic signaling. Mechanisms regulating vascular growth effects of TRPM7 are unclear, but epidermal growth factor (EGF) may be important because it is a magnesiotropic hormone involved in cellular Mg2+ regulation and VSMC proliferation. Here we sought to determine whether TRPM7 is a downstream target of EGF in VSMCs and if EGF receptor (EGFR) through TRPM7 influences VSMC function.

Approach and results: Studies were performed in primary culture VSMCs from rats and humans and vascular tissue from mice deficient in TRPM7 (TRPM7+/Δkinase and TRPM7R/R). EGF increased expression and phosphorylation of TRPM7 and stimulated Mg2+ influx in VSMCs, responses that were attenuated by gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor) and NS8593 (TRPM7 inhibitor). Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) studies, proximity ligation assay (PLA) and live-cell imaging demonstrated interaction of EGFR and TRPM7, which was enhanced by EGF. PP2 (c-Src inhibitor) decreased EGF-induced TRPM7 activation and prevented EGFR–TRPM7 association. EGF-stimulated migration and proliferation of VSMCs were inhibited by gefitinib, PP2, NS8593 and PD98059 (ERK1/2 inhibitor). Phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK1/2 was reduced in VSMCs from TRPM7+/Δkinase mice, which exhibited reduced aortic wall thickness and decreased expression of PCNA and Notch 3, findings recapitulated in TRPM7R/R mice.

Conclusions: We show that EGFR directly interacts with TRPM7 through c-Src-dependent processes. Functionally these phenomena regulate [Mg2+]i homeostasis, ERK1/2 signaling and VSMC function. Our findings define a novel signaling cascade linking EGF/EGFR and TRPM7, important in vascular homeostasis.

Keywords: EGF, TRPM7, vascular smooth muscle

Introduction

Transient receptor potential (TRP) melastatin 7 (TRPM7) is a ubiquitously expressed bi-functional protein comprising a cation channel and a C-terminal α-kinase domain [1,2]. The ion channel is highly permeable to divalent cations, including Mg2+, Zn2+ and Ca2+ [3]. The kinase domain of TRPM7 phosphorylates several targets including calpain-II, annexin-1, myosin IIA, phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2), eukaryotic elongation factor 2-kinase (eEF2-k) and Smad2 [1,4]. Mg2+ is an essential divalent cation that is involved in many cellular processes such as DNA stability, cell metabolism and cell growth [4,5]. Exact mechanisms underlying intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis remain unclear, but several channels and transporters have been implicated including TRPM6, TRPM7 and SLC41A1 [6]. Of these, TRPM7 is most widely expressed and is particularly important in the cardiovascular system [7]. TRPM7 is essential in the prenatal development because a null mutation in the TRPM7 locus triggers early embryonic mortality [8]. Early cardiac TRPM7-deletion results in congestive heart failure and death by hypoproliferation of myocardium [9]. TRPM7 is required to maintain cardiac automaticity in sinoatrial node (SAN) and regulates SAN fibrosis induced by angiotensin II (Ang II) through Smad signaling [9,10]. Using mice heterozygous for the truncation mutation in TRPM7 (TRPM7+/Δkinase), we demonstrated that TRPM7 deficiency is associated with cardiovascular inflammation and fibrosis and increased susceptibility to Ang II-induced endothelial dysfunction and hypertension [11,12]. At the cellular level, we showed that in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) TRPM7 attenuates aldosterone-induced pro-inflammatory signaling [13]. We also found that TRPM7 plays an essential role in VSMC proliferation in a Mg2+-dependent fashion [14] and control of vasoactive agents such as Ang II and growth factors, including epidermal growth factor (EGF) [15].

EGF binds to its EGF receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase and is a key regulator of vascular function [16]. Activation of EGFR is associated with autophosphorylation at key tyrosine residues, leading to activation of multiple downstream signaling cascades such as the Src family kinases and mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases [17]. In addition, in VSMCs, EGF/EGFR activates Ca2+ channels such as TRP classical (TRPC) type 3 and 6 and TRPM4 channels, and voltage-dependent calcium channels, thereby potentiating Ca2+-regulated myogenic tone [18,19]. EGF has also been shown to influence TRPM6 in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (HEK-293) cells, a human embryonic kidney cell line and TRPM7 in A549 cells, a human alveolar adenocarcinoma cell line [20,21]. Activation of EGFR promotes VSMC proliferation, migration, inflammation and fibrosis, processes involved in vascular remodeling in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and atherosclerosis [16]. Through its mitogenic signaling and dysregulated trafficking, EGFR has also been defined as an oncogenic driver that plays an important role in the progression of many epithelial cell cancers [22].

Inhibition of EGFR and its downstream signaling targets ameliorate endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling in experimental models of hypertension [19]. In addition, molecular targeted inhibitors of EGFR are currently used as anticancer therapies [22,23]. Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib, afatinib, erlotinib and osimertinib and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies including cetuximab and panitumumab, prolong survival in cancer patients [24]. An unexpected adverse effect of EGFR inhibition in cancer patients is hypomagnesemia [25,26]. The severity of hypomagnesemia is associated with efficacy of EGFR inhibition and hypomagnesmia has been suggested to be a biological marker of therapeutic effectiveness in some cancers [27,28]. The exact cause of EGFR inhibitor-induced hypomognesemia remains unclear. In vitro studies in HEK-293 cells suggest that abnormal TRPM6-induced Mg2+ may be important, while in vivo studies failed to show a role for renal TRPM6 in plasma levels of Mg2+ [20,29,30].

Given the important role of EGF, Ca2+, Mg2+ and TRPM7 in VSMCs, we sought to evaluate whether EGF signals through TRPM7-dependent processes and if this influences VSMC function and vascular morphogenesis. We also investigated molecular mechanisms linking EGFR and TRPM7 in VSMCs, focusing on c-Src as a putative point of cross-talk.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experimental procedures on rats and mice that were performed at the University of Glasgow were approved by the University of Glasgow Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Board in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 (Licence No. 70/9021) and the ARRIVE Guidelines. Tissues from TRPM7 ‘kinase-dead’ mice (TRPM7R/R) were provided by Dr. Chubanov, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München. TRPM7R/R mice were handled according to the European Union Animal Welfare Act and the local councils on animal care (permits AZ: 55.1-8791-14.718 and 55.2-1-54-2532-180-2016 from Government of Oberbayern).

Studies were performed in primary culture VSMC from Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rats, TRPM7-kinase deficient mice (TRPM7+/Δkinase) and humans. Some experiments were also conducted in intact aorta from TRPM7+/Δkinase mice [8,12] and from mice with global kinase-dead point mutation in TRPM7 (TRPM7R/R) [3]. These mice have been comprehensively phenotyped [11].

WKY rats

WKY rats were housed in individual cages under controlled conditions of 22–24°C and a 12-h light/dark cycle with freely accessible food and tap water. Sixteen-week-old male WKY rats were killed and mesenteric arteries were isolated for primary culture of VSMCs.

Wildtype and TRPM7 kinase-deficient mice

Wildtype (WT) mixed background (C57BL/6J and SV129) TRPM7 kinase-deficient mice (TRPM7+/Δkinase) mice were generated as previously described [8,11]. In TRPM7+/Δkinase mice, TRPM7 protein is truncated immediately upstream of the α-kinase domain associated with reduced channel activity [8]. 18-22 week-old male mice were killed aortae collected, and mesenteric arteries dissected for isolation of primary culture of VSMCs. Aortic segments were snap-frozen for later analysis.

WT C57BL/6 and TRPM7 kinase-dead mice

Aortic tissue from WT C57BL/6 and TRPM7 kinase-dead mice (TRPM7R/R) mice has been reported previously [31,32]. The TRPM7R/R locus contains a ‘kinase-dead’ K1646R point mutation, which specifically abrogates the catalytic activity of TRPM7 kinase domain in the whole organism.

Cell culture

VSMCs from WKY rats

Primary VSMCs were isolated from mesenteric arteries of four to eight animals by enzymatic digestion as we previously described [33]. Rat VSMCs (rVSMCs) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Penicillin/Streptomycin (50 µg/ml), all from Life Technologies. Confluent cells were rendered quiescent overnight in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS before experiments. rVSMCs were studied at passages 4–8.

VSMCs from humans

Studies were conducted under ethics approval obtained from the West of Scotland Research Ethics Service (WS/12/0294) and all subjects provided written informed consent. Small arteries were dissected from surplus surgical tissue of patients receiving elective craniofacial surgeries at the Craniofacial/Oral and Maxillofacial Unit, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow.

Primary human VSMCs (hVSMCs) were isolated from 12 individuals as we previously described [34] and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with Smooth Muscle Growth Supplement (SMGS) (Life Technologies, Paisley, U.K.) and antibiotics. Confluent cells were rendered quiescent overnight using DMEM containing 0.5% FBS before experiments. hVSMCs were studied up to passages 5–8.

VSMCs from WT and TRPM7+/Δkinase mice

Mesenteric beds were dissected from four to eight animals from each group and primary VSMCs were isolated by enzymatic digestion [34]. Mouse VSMCs (mVSMCs) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Confluent cells were rendered quiescent overnight with DMEM containing 0.5% FBS before experiments. mVSMCs were studied at passages 3–7.

Experimental protocols

Quiescent VSMCs were stimulated with EGF (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems) (5 min to 24 h). In some experiments, VSMCs were pre-exposed (for 30 min) to pharmacological modulators including gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor that reversibly binds to the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR and inhibits receptor autophosphorylation by preventing its binding to ATP, 1 µM), apamin (small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel (SK channel) inhibitor, 1 µM), PP2 (c-Src inhibitor, 10 µM), PD98059 (MEK1/2 inhibitor, 20 µM), 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) (non-specific TRPM7 inhibitor, 30 µM) and NS8593 (specific TRPM7 inhibitor, 40 µM) [35]. Concentrations used were based on previous studies [36,37]. Considering potential non-specificity of TRPM7 pharmacological inhibitors, we used two different agents: 2-APB and NS8593.

Immunoblotting

VSMCs and tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer containing Tris 50 mM, pH 8.0, NaCl 150 mM, Triton X-100 1%, SDS 0.1%, supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) 1 mM, pepstatin A 1 µg/ml, leupeptin 1 µg/ml, aprotinin 1 µg/ml (Sigma–Aldrich), sodium fluorate 10 mM (AnalaR Normapur; VWR International), and sodium orthovanadate 1 mM (Alfa Aesar). Total protein lysate was sonicated, followed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants were collected and protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Proteins (20–30 µg) were separated by electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. For proteins with MW higher than 150 kDa, such as Notch3 (270 kDa), TRPM7 (210 kDa) and TRPM6 (210 kDa), we used 7.5% SDS/PAGE gel electrophoresis. Proteins lower than 150 kDa such as ERK (42 kDa), p38 MAPK (38 kDa), Src (60 kDa) and PCNA (35 kDa), we used 10% SDS/PAGE gel electrophoresis. Non-specific bindings sites were blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat dried milk solubilized in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution with 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies diluted (1:1000) in TBS-T containing 3% (m/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma–Aldrich,): TRPM7 (cat.#: ab245408, specific for humans and mice), TRPM6 (cat.#: ab79227), SLC41A1 (cat.#: ab83701) and α-tubulin (1:2000; cat.#: ab4074), phospho-EGFR (Y845; cat.#: ab194756), purchased from Abcam; TRPM7 (cat.#: MA5-27620, specific for humans, mice and rats), acquired from Invitrogen; EGFR (cat.#: 2646S), phospho-p38 MAPK (T180/Y182; cat.#: 9211S), p38 MAPK (cat.#: 9212S), phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204; cat.#: 9101S), ERK1/2 (cat.#: 9102S), phospho-Src (Tyr416; cat.#: 2101S) and Src (cat.#: 2109), purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies; β-actin (1:10000; cat.#: A2228), purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Phospho-TRPM7 (Ser1511, rabbit) antibody was produced by our collaborator Dr. Chubanov (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München) and previously validated [38,39]. Subsequently, membranes were washed and then incubated with secondary fluorescence-coupled antibodies anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 680 or anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 800 (Thermo Fisher) diluted (1:10000) in TBS-T containing 1% (m/v) BSA at room temperature for 1 h. An infrared laser scanner (Odyssey Clx, Li-COR) was used to visualize the membranes, and images were analyzed using the software Image Studio™ Lite free version (LICOR, Cambridge, U.K.).

Immunoprecipitation

VSMCs were harvested and homogenized in HEPES buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM d-glucose and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), supplemented with PMSF 1 mM, pepstatin A 1 µg/ml, leupeptin 1 µg/ml, aprotinin 1 µg/ml (Sigma–Aldrich), sodium fluorate 10 mM (AnalaR Normapur; VWR International), and sodium orthovanadate 1 mM (Alfa Aesar). A total of 200 µl of VSMCs lysate containing 400 µg of protein was mixed with 2 µl of primary antibody (1:100) and the reaction mixture was rotated in a Stuart SB3 Rotator (Camlab Ltd) at a gentle speed overnight at 4°C. The following day, 15 µl of Protein A and 15 µl of Protein G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added to the reaction mixture followed by rotation at 4°C for 4 h. The immunoprecipitation (IP) complex was then washed twice in lysis buffer followed by centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 30 s. The pellet was collected and prepared for immunoblotting.

Measurement of Ca2+ mobilization

Intracellular Ca2+ levels in VSMCs were assessed using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Cal-520 acetoxymethyl ester (Cal-520AM; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.). Quiescent VSMCs cultured in 12-well plates were incubated with 10 μM Cal-520AM in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS at 37°C for 75 min, followed by 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the dye solution was replaced with HEPES buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM d-glucose and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for 30 min. In some experiments, inhibitors such as gefitinib (1 µM), NS8593 (40 µM) and 2-APB (30 µM) were added 30 min prior to stimulation with EGF (50 ng/ml). Fluorescent Cal-520AM-Ca2+ signals were recorded by an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Live-Cell imaging system, ZEISS, Cambridge, U.K.) at excitatory wavelength of 490 nm and emission of 535 nm. Data were acquired and analyzed using Zen Pro (ZEISS).

Measurement of intracellular Mg2+

Intracellular Mg2+ levels in VSMCs were measured using the specific fluorescent probe Magnesium Green AM (Thermo Fisher, cat.#:M3735) as we previously described [11]. Briefly, VSMCs were kept in Ca2+/Mg2+-free HEPES buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM d-glucose and 20 mM HEPES) and incubated with 5 μM Magnesium Green for 30 min at 37°C in dark and in constant gentle agitation to prevent cell adhesion. Subsequently, the stained cells were washed twice using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 3 min at room temperature. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in HEPES buffer with 1 mM Mg2+ (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM d-glucose, 20 mM HEPES and 1 mM MgCl2). Cells were left at room temperature for 15 min to allow complete de-esterification of intracellular AM esters, followed by stimulation with EGF (50 ng/ml) for 5 min. In some studies, inhibitors such as gefitinib (1 µM), NS8593 (40 µM), apamin (1 µM), PP2 (10 µM) and 2-APB (30 µM) were added 30 min prior to EGF stimulation. Fluorescent signals of Magnesium Green were acquired using Flow Cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed by FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, U.S.A.).

Cell migration

VSMCs migration was assessed using the scratch-wound assay, a two-dimensional (2D) in vitro technique [40]. Confluent VSMCs cultured in 12-well plates were rendered quiescent overnight using DMEM with 0.5% FBS. The following day, a sterile pipette tip was used to scratch the cell monolayer, making a straight ‘wound’ with equal width. The medium was then replaced with fresh serum-free DMEM to remove floating cells and reduce the effects of cell proliferation. At zero-hour (0 h) time, three photos were taken from each well using a 10× objective (EVOS XL Core, Thermo Fisher). Cells were then incubated with EGF (50 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of inhibitors including gefitinib (1 µM), NS8593 (40 µM), 2-APB (30 µM) and PD98059 (20 µM). After 20 h, three photos were taken in the same areas for each well. Images were collected and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, U.S.A.). Cell migration was calculated as the percentage of wound healing closure at 20 h relative to 0 h time point.

Proliferation assay

The cell tracking dye carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; cat.#: C34554, Thermo Fisher) was used in the proliferation assay. Following each cell division, the fluorescein-tagged cellular molecules are split evenly in two daughter cells, and cell proliferation can be assessed by measuring CFSE fluorescence. Briefly, isolated VSMCs were incubated with 5 µM CFSE in 1 ml of PBS containing 1% (v/v) FBS for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, CFSE-labeled cells were washed twice using DMEM, and then plated at ∼30% confluence in six-well plates using DMEM with 10% FBS. The following day, medium was replaced with DMEM with 5% FBS and cells were then cultured for 72 h. During this period, cells were treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of inhibitors including gefitinib (1 µM), NS8593 (40 µM), 2-APB (30 µM) and PD98059 (20 µM). After 72 h, cells were harvested in PBS containing 1% FBS and CFSE fluorescence was detected with an FITC channel, using Flow Cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, U.S.A.).

Histology

Aortic segments from WT and TRPM7+/Δkinase mice were fixed in 10% buffered-formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5-µm-thick) were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE). Briefly, aorta sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in two 7-min changes of Histo-Clear (Fisher Scientific Ltd) and graded ethanol solutions (100, 95 and 70%, 7 min each), followed by 7 min in distilled water. Next, nuclei were stained with Harris’ modified Hematoxylin (Cell Pathology Ltd) for 2 min and then rinsed in running tap water for 5 min followed by 30 s in 70% ethanol. Cytoplasmic structures were stained using Eosin Y solution (Sigma–Aldrich) for 2 min. Consequently, tissue sections were rinsed in graded ethanol solution (95% for 30 s, 100% for 1 and 7 min separately), followed by two 5-min changes in Histo-Clear. Tissue sections were then mounted with glass coverslips using DPX non-aqueous mounting medium (Merck Millipore). Images were acquired using a light microscope (ZEISS) with 20× and 40× objective and were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Confocal microscopy

rVSMCs from WKY were seeded on cover glasses (13 mm, Thickness No. 0; VWR) at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates. After stimulation, cells were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and permeabilized with Triton X-100 (Sigma–Aldrich) in PBS for 4 min at room temperature. After three washes with TBS (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.6), cells were blocked with 10% goat serum and 2% BSA (w/v) in TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times using TBS and incubated with specific primary antibodies to: TRPM7 (cat.#: MA5-27620; Invitrogen; 1:300) and EGFR (cat.#: 2646S; Cell Signaling; 1:300) overnight. The following day, cells were washed and then incubated with 1:400 diluted secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 555 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (cat.#: A-21428; Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Mouse IgG (cat.#: A-11001; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade mounting medium with DAPI (cat.#: P36935; Invitrogen). Staining were visualized using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM880) with a 40× (NA 1.1) water-immersion objective. Images were analyzed using the open source Fiji software (NIH, Bethesda, U.S.A.).

Live-cell imaging of intracellular TRPM7 movement

HEK-293 expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged WT mouse TRPM7 (WT mTRPM7-YFP) [41]. The transient transfected HEK-293 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS. After EGF (50 ng/ml) treatment, fluorescent signal of TRPM7 in HEK-293 cells were recorded for 15 min on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Live-Cell imaging system, ZEISS) at excitatory wavelength of 490 nm and emission of 535 nm. Images were quired and analyzed by Zen Pro software (ZEISS).

Proximity ligation assays

VSMCs from WKY were seeded on cover glasses (13 mm, Thickness No.0; VWR) at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates. The following day, cells were stimulated with EGF (50 ng/ml) for 5 min with or without 30 min pre-treatment of inhibitors. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, and cell membranes were then stained by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; cat.#: w6748; Invitrogen) for 25 min, followed by permeabilization using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma–Aldrich) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with Buffer A (0.01 M Tris-Base, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.4) and blocked using Blocking Buffer for 1 h at 37°C, followed incubation with primary antibodies EGFR (cat.#: 2646S; Cell Signaling; 1:100) and TRPM7 (cat.#: MA5-27620; Invitrogen; 1:100) overnight at 4°C. The following day, proximity ligation assay (PLA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Duolink Detection Kit (Sigma–Aldrich). Briefly, cells were washed using Buffer A and incubated with Duolink® In Situ PLA® Probe Anti-Mouse PLUS (cat.#: DUO92001) and Duolink® In Situ PLA® Probe Anti-Rabbit MINUS (cat.#:DUO92005) at 37°C for 1 h to label TRPM7 and EGFR, respectively. Circular DNA molecules were formed in Ligation Buffer (working dilution 1:5) containing DNA Ligase (1:40) at 37°C for 30 min, and were amplified in Amplification Buffer (1:5) containing the rolling circle polymerase (1:80) at 37°C for 100 min. Coverslips were mounted with Duolink® In Situ Mounting Medium with DAPI (cat.#: DUO82040; Sigma–Aldrich). Images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 5 PASCAL ZEISS) under an oil immersion objective (63×/1.4 NA). In order to detect all PLA signals, a series of Z-stack images were collected and were analyzed by ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Pad 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). Unpaired and two-tailed t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s or Tukey’s post-test were used as appropriate. Results of statistical tests with P-value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

EGF regulates TRPM7 but not TRPM6 and SLC41A1 through EGFR and c-Src dependent mechanisms in rVSMCs

rVSMCs express EGFR and TRPM7 (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S1A,B). EGF stimulation for 24 h increased TRPM7 expression in rVSMCs, an effect that was attenuated in cells pretreated with gefitinib and PP2 (Figure 1A). EGF had no effect on expression of other Mg2+ channels and transporters like, TRPM6 and SLC41A1 (Supplementary Figure S1C,D).

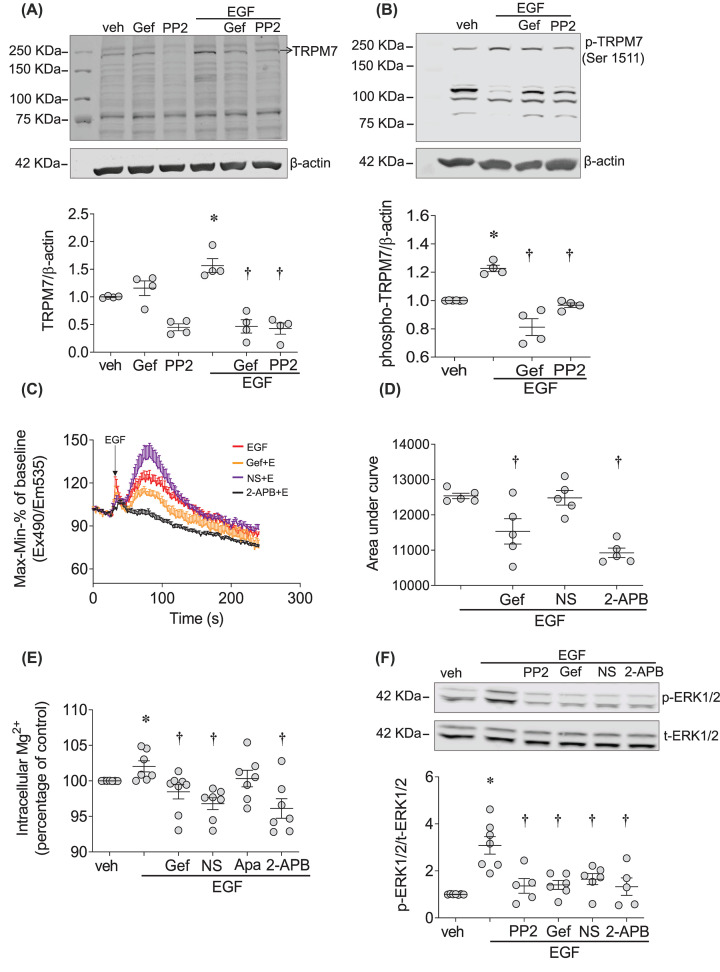

Figure 1. EGF regulates TRPM7 and signaling through EGFR and c-Src in rVSMCs.

(A,B) rVSMCs were treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of EGFR inhibitor gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM) and c-Src inhibitor PP2 (10 µM). (A) TRPM7 expression, normalized to β-actin, after 24 h stimulation and (B) TRPM7 phosphorylation, normalized to β-actin, after 5-min stimulation. Upper panels are representative immunoblots. (C,D) Intracellular Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]i) in rVSMCs induced by EGF (50 ng/ml) were measured in the presence and absence of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM), the TRPM7 inhibitor NS8593 (NS, 40 µM) and the non-selective cation channel inhibitor 2-APB (30 µM) in rVSMCs. (D) [Ca2+]i data are expressed as (C) fluorescence Cal-520AM-Ca2+ signals and (D) calculated as the area under curve. (E) Intracellular free Mg2+ ([Mg2+]i ) in rVSMCs after EGF (50 ng/ml) treatment (5 min) in the presence and absence of gefitinib (1 µM), NS8593 (40 µM), apamin (Apa, 1 µM) and 2-APB (30 µM) were measured by Flow Cytometry using specific Mg2+ indicator Magnesium Green AM. Raw data were normalized to percentage differences based on the baseline value (veh). (F) ERK1/2 activity was assessed by phosphorylation levels (p-ERK1/2) normalized by total ERK1/2 (t-ERK1/2) expression. Results are mean ± SEM of four to eight experiments. *P<0.05 compared with vehicle control (veh, PBS) and †P<0.05 compared with EGF-treated cells.

To determine whether EGF influences the activity of TRPM7-kinase, we assessed the autophosphorylation site at the Ser1511 domain, which is critically involved in TRPM7-kinase activation and signaling [39,42]. As shown in Figure 1B, EGF induced a rapid increase (within 5 min) in phosphorylation of TRPM7. This was significantly blunted by gefitinib and PP2 (Figure 1B).

EGF influences VSMC Mg2+ but not Ca2+ transients through TRPM7-dependent pathways in rVSMCs

As TRPM7 is a divalent cation channel important in the regulation of Mg2+ and Ca2+ in VSMC, we investigated its role in EGF-induced changes in intracellular levels of Ca2+ and Mg2+. In rVSMCs, EGF stimulation increased Ca2+ transients, which was reduced by gefitinib and 2-APB (Figure 1C,D). NS8593, a more selective TRPM7 inhibitor [43], did not affect Ca2+ influx induced by EGF. Intracellular Mg2+ levels were increased in rVSMCs stimulated with EGF (5 min), an effect that was reduced by gefitinib, 2-APB and NS8593 (Figure 1E). Since NS8593 is also an inhibitor of SK channels [43], we used the selective SK channel inhibitor apamin as a control, which failed to change EGF effects on [Mg2+]i.

EGF-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 involves c-Src and TRPM7

MAPKs, such as ERK1/2 and c-Src signaling are important downstream targets of EGF. EGF-induced phosphorylation of c-Src in rVSMCs. To evaluate the role of c-Src and TRPM7 in this pathway, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was assessed in EGF-stimulated rVSMCs in the presence of PP2, gefitinib, and TRPM7 inhibitors NS8593 and 2-APB. As shown in Figure 1F, EGF significantly increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in rVSMCs. These effects were blunted when EGFR, c-Src and TRPM7 were inhibited.

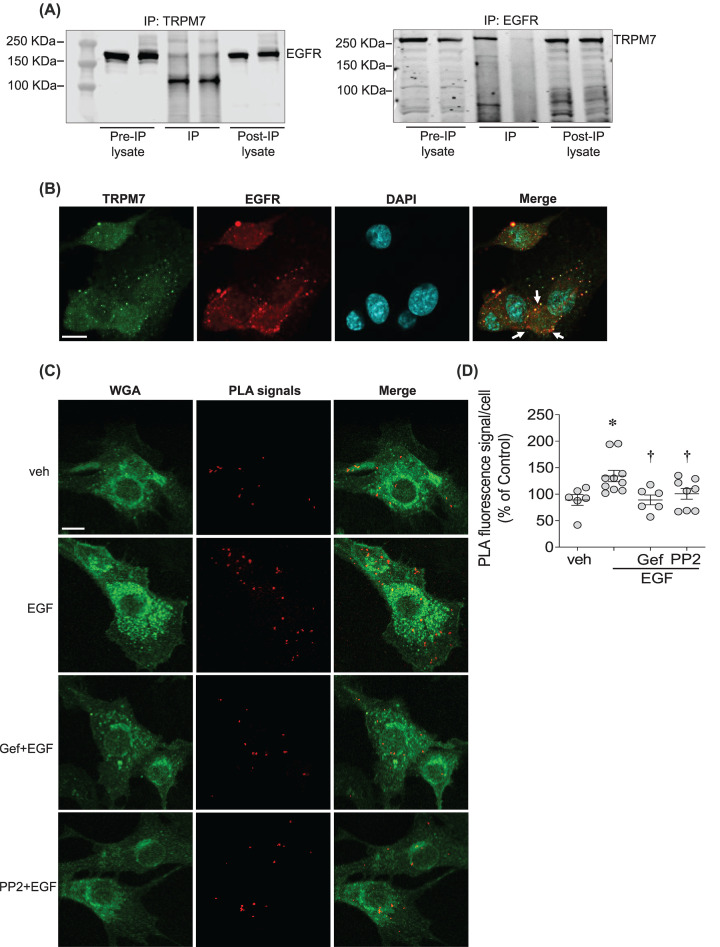

EGF enhances interaction between EGFR and TRPM7 in a c-Src-dependent manner

As shown in Figure 2A, EGFR was detected in rVSMCs when TRPM7 was immunoprecipitated. The association between EGFR and TRPM7 was further confirmed when TRPM7 was detected after EGFR IP. TRPM7–EGFR interaction was also determined by confocal microscopy showing co-localization in the cell membrane (Figure 2B) and by PLA, using specific primary antibodies to EGFR and TRPM7. Figure 2C,D show that in basal conditions, there are PLA positive signals, indicating interaction between EGFR and TRPM7 in the cell membrane. PLA positive signals were increased by EGF stimulation, and reduced by gefitinib and PP2 (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2. EGF enhances direct interaction between EGFR and TRPM7 in a c-Src-dependent manner.

(A) EGFR was detected when TRPM7 was immunoprecipitated in rVSMCs using anti-TRPM7 antibody (left panel) and TRPM7 was detected when EGFR was immunoprecipitated using anti-EGFR antibody (right panel) (n=3–4). (B) Representative confocal microscopy images of rVSMCs co-immunostained for TRPM7 (Alexa 488, green) and EGFR (Alexa 555, red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (n=3). (C,D) PLA was used to visualize and quantify TRPM7-EGFR interaction in rVSMCs stimulated with vehicle (veh), and EGF (50 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of gefitinib (1 µM) and PP2 (10 µM). WGA (Alexa 488, green) was used to stain cell membranes. Red fluorescence is identified as PLA positive signals. Orange fluorescence in the merged figure identifies co-localization. PLA signals were quantified using the Analyse Particles plugin of ImageJ software. For each condition, quantifications were performed from at least 100 cells and expressed as the mean number of signals per cell (percentage of control). Scale bar =10 µm. Arrows indicate co-localization of EGFR and TRPM7. *P<0.05 compared with vehicle control (veh, PBS) and †P<0.05 compared with EGF-treated cells.

EGF/EGFR does not influence TRPM7 trafficking in HEK-293 cells

Previous studies in kidney cell lines demonstrated that EGF promotes TRPM6 trafficking from the cytosol to the cell membrane [20]. Having demonstrated that TRPM7 is cell membrane-associated, we questioned whether EGF influences TRPM7 trafficking, as reported for TRPM6 in kidney cells. Using YFP-TRPM7, HEK-293 cells we assessed effects of EGF stimulation on TRPM7 mobilization. As shown in Supplementary Figure S2A,B and Supplementary Video S1 EGF did not influence TRPM7 translocation to the cell membrane, at least for the time period studied (10 min).

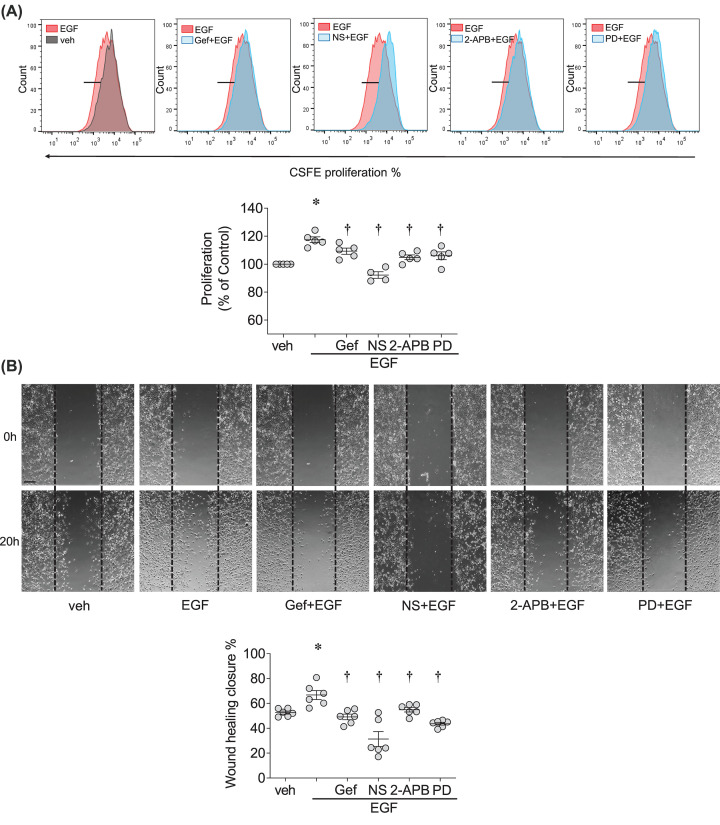

EGF promotes VSMCs migration and proliferation through TRPM7 and ERK1/2

Considering that VSMC proliferation and migration are key processes involved in vascular physiology, we assessed the importance of TRPM7 in these functional effects mediated by EGF. Using the CFSE proliferation assay, we found that EGF induced proliferation of rVSMCs in an EGFR–TRPM7–ERK1/2-dependent manner, since EGF stimulated cell growth, effects that were inhibited by gefitinib, TRPM7 inhibitors and the ERK1/2 inhibitor, PD98059 (Figure 3A). To further assess the functional significance of EGF–TRPM7–ERK1/2, we examined VSMC migration using the scratch-wound assay. As shown in Figure 3B, EGF significantly enhanced rVSMCs migration. This was inhibited by gefitinib, NS8593, 2-APB and PD98059.

Figure 3. EGF promotes VSMCs migration and proliferation through TRPM7 and ERK1/2.

rVSMCs were stimulated with EGF (50 ng/ml), with or without 30 min pre-treatment of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM), NS8593 (NS, 40 µM), 2-APB (30 µM) and ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (PD, 20 µM). (A) Cell proliferation was assessed by CFSE proliferation assay using flow cytometry. Upper panel: Representative flow cytometry histograms. Lower panel: Corresponding scatter-plot graphs showing cell proliferation rate. Raw data were normalized to percentage differences based on the baseline value (veh). (B) Cell migration was examined by Scratch-wound assay. Cell migration was calculated as the percentage of wound healing closure at 20 h relative to 0 h time point. Upper panel: Representative images of rVSMCs migration stimulated with EGF in the presence and absence of different inhibitors. Lower panel: Corresponding scatter-plot graphs showing cell migration rate calculated as wound healing closure. Scale bar = 150 µm. *P<0.05 compared with vehicle control (veh, PBS) and †P<0.05 compared with EGF. Results represent the mean ± SEM of four to six independent experiments.

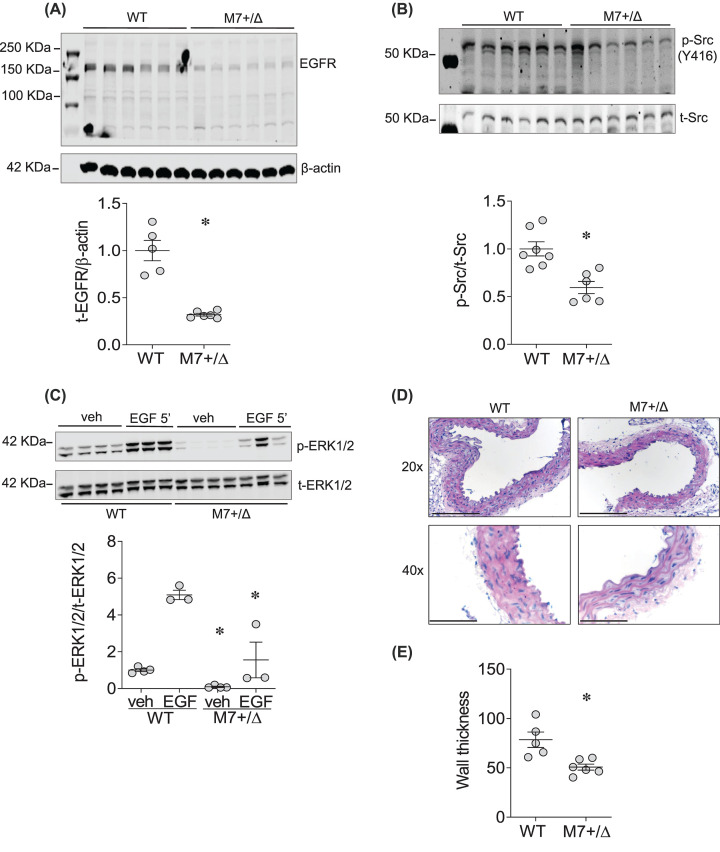

EGFR and c-Src are regulated by TRPM7-dependent mechanisms

Having demonstrated a feedforward loop between EGF/EGFR/c-Src and TRPM7 where interactions between EGFR and TRPM7 may be crucial for EGF signaling, we questioned whether TRPM7 plays a role in regulating vascular EGFR and c-Src. To address this, we evaluated the expression and phosphorylation of EGFR, c-Src and ERK1/2 in VSMCs and intact vascular tissue from mice deficient in TRPM7 (Figure 4A–C). TRPM7+/Δkinase mice, characterized by reduced expression and phosphorylation of TRPM7 (Supplementary Figure S3) had significantly reduced expression and phosphorylation of EGFR and c-Src.

Figure 4. Reduced expression of EGFR is associated with vascular remodeling in TRPM7-deficient mice.

(A) EGFR expression (EGFR) in mVSMCs derived from WT and TRPM7 kinase-deficient mice (TRPM7+/Δkinase, M7+/Δ). Protein expression normalized to β-actin. (B) c-Src phosphorylation (p-c-Src), normalized by total c-Src expression (t-Src) in mVSMCs derived from WT and TRPM7+/Δkinase mice. (C) ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultured mVSMCs derived from WT and TRPM7+/Δkinase (M7+/Δ) mice, at basal levels (veh) and after 5-min treatment with EGF (50 ng/ml). ERK1/2 activity was assessed by phosphorylation level (p-ERK1/2) and normalized by total ERK1/2 expression (t-ERK1/2). Results are mean ± SEM of three to six experiments. (D,E) Representative images and quantification of aortic wall thickness in WT and TRPM7+/Δkinase mice; 20×: Scale bar =150 µm. 40×: Scale bar =75 µm. Results represent the mean ± SEM of three to seven independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with WT mice.

Reduced phosphorylation of EGFR is associated with vascular remodeling in TRPM7-deficient mice

EGF-induced proliferation and migration of VSMCs are major factors involved in vascular morphology and structure. We investigated the effects of TRPM7 deficiency on EGFR expression and vessel morphology by studying aorta from TRPM7+/Δkinase mice. These processes were associated with significant changes in vascular morphology as evidenced by significantly reduced vascular thickness in TRPM7+/Δkinase mice (Figure 4D,E). Further demonstrating a critical role for EGFR and TRPM7 in vascular homeostasis, we found that expression of PCNA, a pro-prolifeartive marker and Notch3, a cell surface receptor expressed in VSMCs critically involved in vascular structure and development [44], was reduced in mVSMCs and aortas from TRPM7+/Δkinase mice (Supplementary Figure S4A–C).

We also examined aortae from TRPM7R/R mice, another model of TRPM7 deficiency. As shown in Supplemental Figure S5, aortae from TRPM7R/R mice exhibited reduced phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK1/2.

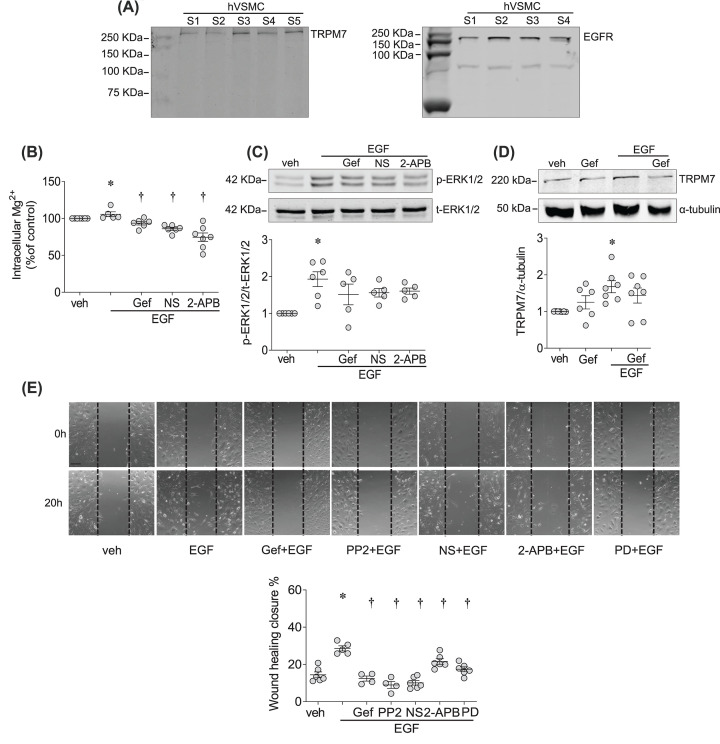

EGF/EGFR signaling and TRPM7 in hVSMCs

Next, we investigated whether the novel EGF-TRPM7 pathway observed in cells and tissues from rodents is also evident in humans. We confirmed that primary hVSMCs express TRPM7 and EGFR (Figure 5A). EGF stimulation (5 min) induced a significant increase in [Mg2+]i and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, effects that were attenuated by gefitinib, NS8593 and 2-APB (Figure 5B,C). Long-term stimulation (5 h) with EGF increased TRPM7 expression, which was abolished by gefitinib (Figure 5D). To test the functional significance of these events, we assessed EGF-induced migration of hVSMCs. As shown in Figure 5E, EGF stimulation significantly increased migration of hVSMCs. These responses were reduced by gefitinib, PP2, NS8593, 2-APB and PD98059, demonstrating that EGF-induced migration of hVSMC involves c-Src–TRPM7–ERK1/2-dependent pathways.

Figure 5. EGF/EGFR signaling and TRPM7 in hVSMCs.

(A) Total cell lysate from hVSMC was probed for TRPM7 (left panel) and EGFR (right panel) expression. Samples S1–S5 were hVSMCs derived from five different donors. (B) [Mg2+]i in hVSMCs exposed to EGF (50 ng/ml) for 5 min in the absence or presence of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM), NS8593 (NS, 40 µM) and 2-APB (30 µM). (C) ERK1/2 phosphorylation, normalized to total ERK1/2 expression, in hVSMCs exposed to EGF (50 ng/ml) for 5 min in the presence or absence of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM), NS8593 (NS, 40 µM) and 2-APB (30 µM). (D) TRPM7 expression after 5 h treatment with EGF (50 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM). (E) Cell migration assessed by Scratch-wound assay in hVSMCs treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) for 20 h in the presence or absence of gefitinib (Gef, 1 µM), PP2 (10 µM), NS8593 (NS, 40 µM), 2-APB (30 µM) and PD98059 (PD, 20 µM). Scale bar = 150 µm. Results represent the mean ± SEM of four to seven independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with vehicle control (veh, PBS) and †P<0.05 compared with EGF.

Discussion

Our study identifies TRPM7 as a signaling target of EGF in VSMCs. In particular we demonstrate that (i) EGF/EGFR induces phosphorylation of TRPM7, important in VSMC [Mg2+]i but not [Ca2+]i homeostasis, (ii) EGFR and TRPM7 physically interact on the cell membrane in a c-Src-dependent manner, (iii) EGF/EGFR-mediated activation of TRPM7 involves c-Src and (iv) EGF/EGFR/c-Src signaling promotes VSMC proliferation and migration through TRPM7-regulated ERK1/2-dependent processes. Moreover, we demonstrate that TRPM7 is both downstream and upstream of EGFR, suggesting that EGFR itself is regulated by TRPM7 in a feedforward manner. Together our data define a novel EGF signaling pathway involving c-Src and TRPM7 and show functional interplay between EGFR and TRPM7, important in the regulation of vascular homeostasis.

Vascular effects of EGF are mediated via well-defined signaling pathways involving MAPKs, phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K), PLC-γ, c-Src and transactivation by G protein-coupled receptors [16]. Here we advance the field by delineating a role for TRPM7. This phenomenon seems to be highly regulated and cell-specific, because in VSMCs EGF did not influence TRPM6 or the other Mg2+ transporter SLC41A1, but increased activity of TRPM7, whereas in renal tubule epithelial cells, EGFR activation stimulates TRPM6 but not TRPM7 [20].

The molecular significance of TRPM7 as a downstream target of EGF in the vascular system is still unclear but likely relates to its role as a cation channel, since EGF influences cellular Ca2+ and Mg2+ homeostasis, critically involved in VSMC regulation [8,45,46]. EGF signaling through Ca2+, a pivotal second messenger in VSMCs, has been well described [16], but there is a paucity of information about EGF and [Mg2+]i. The first evidence suggesting a link between EGF and Mg2+ homeostasis derived from clinical studies. Individuals with EGF mutations were shown to have associated isolated recessive renal hypomagnesemia [29] and cancer patients treated with the EGFR inhibitor cetuximab have reduced serum Mg2+ levels that normalize upon therapy withdrawal [25,26]. Our findings in rat and human VSMCs further support the notion that EGF influences intracellular cation homeostasis. This seems to be more important for Mg2+ than Ca2+ because the TRPM7 inhibitor NS8593 attenuated Mg2+ but not Ca2+ responses, whereas the non-specific inhibitor of TRP channels 2-APB [47] reduced both Ca2+ and Mg2+ transients. Corroborating our findings others showed that in cancer cells EGF influences Ca2+ in a TRPM7-independent manner probably through other TRP channels [48]. To explore potential molecular mechanisms whereby EGF influences TRPM7, we focused on c-Src, a key downstream kinase of EGFR activation [49,50]. In particular, PP2, a selective Src inhibitor, decreased activity and expression of TRPM7 in VSMC.

To further explore the relationship between EGF signaling and TRPM7, we employed a multidisciplinary approach of co-IP, live-cell imaging, and PLAs in rodent and hVSMCs, vascular tissue from TRPM7-deficient mice and TRPM7-transfected HEK cells. PLA is a powerful technique to detect, localize and quantify protein–protein interaction, which in combination with co-IP and co-localization experiments, clearly indicated EGFR–TRPM7 interaction in VSMCs. Molecular processes regulating this interaction are unclear but may depend on phosphorylation of the respective partner proteins, involvement of adaptor molecules that promote physical association and localization in subcellular compartments. TRPM7 localizes in intracellular vesicles and traffics to the membrane [51]. In our study TRPM7 clearly co-localized with EGFR on the cell membrane in VSMCs. However, in TRPM7-expressing HEK cells TRPM7 was located primarily in intracellular membrane compartments, similar to what has previously been shown for renal TRPM6 [20]. Hence TRPM7 trafficking may be differentially regulated in a cell-specific manner.

The interplay between EGFR and TRPM7 seems to be circuitous because EGFR is both upstream and downstream of TRPM7. This is supported by the findings that gefitinib inhibited phosphorylation of TRPM7, while TRPM7 deficiency was associated with reduced phosphorylation of EGFR and its downstream target c-Src. Of significance, we focused on phosphorylation of c-Src at tyrosine 416 (Y416), which is associated with high kinase activity, and phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr845 (Y845), a c-Src-dependent phosphorylation site [49,50]. Hence EGF/EGFR-induced activation of TRPM7 influences EGFR phosphorylation and may represent a compensatory mechanism to maintain [Mg2+] homeostasis and EGF signaling in VSMC, especially in pathological conditions associated with abnormal EGF and/or TRPM7 regulation.

A unique feature of TRPM7 is that is has dual properties functioning as an ion channel and as a cytosolic kinase [1,2,4]. It is therefore not surprising that in addition to regulating Mg2+ influx, it participates in downstream signaling and cell function. TRPM7 influences tyrosine kinases, including EGFR and c-Src, as we demonstrate here, as well as MAP kinases [1,4]. Of the MAP kinases, ERK1/2 is especially important in EGF signaling in VSMCs, since it mediates cell growth, migration and contraction [16]. Our study suggests that EGF/EGFR stimulates ERK1/2 signaling through TRPM7-dependent pathways, since pharmacological and genetic inhibition of TRPM7 was associated with reduced EGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Functionally, these processes influence VSMC proliferation and migration, since pharmacological inhibition of EGF, c-Src, ERK1/2 and TRPM7 attenuated EGF-stimulated responses. Previous studies demonstrated a role for TRPM7-ERK1/2 in cell proliferation, with variable responses. In endothelial cells, TRPM7 silencing promoted cell growth via ERK1/2, while in mouse cortical astrocytes, TRPM7 knockdown inhibited proliferation through ERK1/2 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) [52,53]. To explore the biological significance of our cell-based studies, we examined intact vessels from TRPM7+/Δkinase mice, which have EGFR down-regulation, and showed reduced vascular wall thickness with decreased expression of PCNA and Notch3, markers of VSMC proliferation and differentiation, respectively [44,54]. Our observations of decreased aortic phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK1/2 in TRPM7R/R mice, a second model of TRPM7 deficiency, further validates the notion that EGFR signaling is down-regulated when TRPM7 activity is reduced. Together our findings indicate that EGF/EGFR through c-Src-regulated TRPM7 and ERK1/2 signaling, promotes VSMC proliferation and migration, processes that play a role in vascular remodeling.

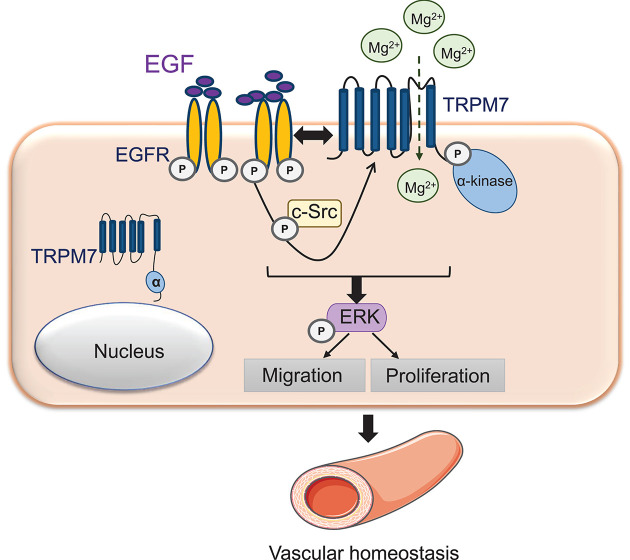

In summary, utilizing a combination of pharmacological, biochemical, imaging and molecular biological approaches together with cells and tissues from rodent models we show important cross-talk between EGFR and TRPM7. We provide new evidence that EGFR directly interacts with TRPM7 in VSMCs and that EGF through c-Src regulates TRPM7 in a feedforward system. Functionally these phenomena regulate [Mg2+]i homeostasis, ERK1/2 signaling and VSMC function (Figure 6). Of significance our results in rodent VSMCs were recapitulated in hVSMCs, indicating clinical relevance. These findings define a novel pathway in VSMCs and highlight important links between EGF signaling and TRPM7, which may be particularly important in conditions associated with EGFR hyperactivation, such as in cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Figure 6. Schematic diagram demonstrating the novel signaling pathway involving EGFR–TRPM7 interaction in VSMCs.

EGFR activation by EGF results in c-Src activation, which is required for TRPM7 activity (phosphorylation and expression) contributing to Mg2+ homeostasis and interaction of EGFR and TRPM7 in the cell membrane. This signaling pathway is required for activation of ERK1/2. Cross-talk between EGF–EGFR and TRPM7 in VSMCs regulates cell migration and proliferation and may play an important role in vascular homeostasis.

Clinical perspectives

EGF receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase signals through multiple pathways and influences cellular cation homeostasis, including Mg2+, important in vascular homeostasis and disease. This is clinically relevant because anticancer EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors cause hypomagnesemia and hypertension. Processes linking vascular EGF/EGFR and Mg2+ are unclear, but the novel Mg2+ transporter TRPM7 may be important.

We demonstrate important interaction between EGFR and TRPM7 in hVSMCs. EGF/EGFR is both upstream and downstream of TRPM7. This interaction involves c-Src and regulates intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis, ERK1/2 signaling and VSMC migration and proliferation.

We identify a novel pathway in VSMCs and highlight important links between EGF signaling and TRPM7. This interplay may be particularly important in conditions associated with EGFR hyperactivation, perturbed cation (Mg2+) regulation and vascular dysfunction, such as in hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank W. Beatie W., J. Thomson and R. Hepburn for technical support.

Abbreviations

- 2-APB

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- hVSMC

human vascular smooth muscle cell

- mVSMC

mouse vascular smooth muscle cell

- PCNA

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PLA

Proximity ligation assay

- rVSMC

rat vascular smooth muscle cell

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation [grant numbers CH/12/429762, 18/6/34217 (to R.M.T.)]; the Walton Fellowship, University of Glasgow (to A.C.M.); the China Scholarship Council Grant [grant number 201708060309 (to Z.-G.Z.)]; and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [grant numbers TRR 152, RTG 2338 (to V.C. and T.G.)].

Author Contribution

R.M.T. designed the study and provided funding, supervision, critical discussion, and support in the preparation and submission of the manuscript. Z.-G.Z. performed experiments, analyzed data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript draft. F.J.R. and A.C.M. designed the study, generated critical discussion, helped to write the manuscript and provided daily laboratory supervision to Z.-G.Z. J.L. and G.S.B. performed the PLA, and X.G. and W.F. helped with HEK cell experiments. V.C. and T.G. provided anti-pTRPM7 antibody, TRPM7 expression plasmids and tissues from TRPM7R/R mice, and contributed to the experimental protocol. K.B.N., R.A.-L. and L.L.C. helped with studies on Ca2+ mobilization, proliferation and IP.

References

- 1.Runnels L.W., Yue L. and Clapham D.E. (2001) TRP-PLIK, a bifunctional protein with kinase and ion channel activities. Science 291, 1043–1047 10.1126/science.1058519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadler M.J., Hermosura M.C., Inabe K., Perraud A.L., Zhu Q., Stokes A.J.et al. (2001) LTRPC7 is a Mg.ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature 411, 590–595 10.1038/35079092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittermeier L., Demirkhanyan L., Stadlbauer B., Breit A., Recordati C., Hilgendorff A.et al. (2019) TRPM7 is the central gatekeeper of intestinal mineral absorption essential for postnatal survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4706–4715 10.1073/pnas.1810633116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou Z.G., Rios F.J., Montezano A.C. and Touyz R.M. (2019) TRPM7, magnesium, and signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 10.3390/ijms20081877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stangherlin A. and O'Neill J.S. (2018) Signal transduction: magnesium manifests as a second messenger. Curr. Biol. 28, R1403–R1405 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolisek M., Sponder G., Pilchova I., Cibulka M., Tatarkova Z., Werner T.et al. (2019) Magnesium extravaganza: a critical compendium of current research into cellular Mg(2+) transporters other than TRPM6/7. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 176, 65–105 10.1007/112_2018_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yogi A., Callera G.E., Antunes T.T., Tostes R.C. and Touyz R.M. (2011) Transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) cation channels, magnesium and the vascular system in hypertension. Circ. J. 75, 237–245 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryazanova L.V., Rondon L.J., Zierler S., Hu Z., Galli J., Yamaguchi T.P.et al. (2010) TRPM7 is essential for Mg(2+) homeostasis in mammals. Nat. Commun. 1, 109 10.1038/ncomms1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sah R., Mesirca P., Mason X., Gibson W., Bates-Withers C., Van den Boogert M.et al. (2013) Timing of myocardial trpm7 deletion during cardiogenesis variably disrupts adult ventricular function, conduction, and repolarization. Circulation 128, 101–114 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong H., Wang T., Lian G., Xu C., Wang H. and Xie L. (2018) TRPM7 regulates angiotensin II-induced sinoatrial node fibrosis in sick sinus syndrome rats by mediating Smad signaling. Heart Vessels 33, 1094–1105 10.1007/s00380-018-1146-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rios F.J., Zou Z.G., Harvey A.P., Harvey K.Y., Nosalski R., Anyfanti P.et al. (2020) Chanzyme TRPM7 protects against cardiovascular inflammation and fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 721–735 10.1093/cvr/cvz164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antunes T.T., Callera G.E., He Y., Yogi A., Ryazanov A.G., Ryazanova L.V.et al. (2016) Transient receptor potential melastatin 7 cation channel kinase: new player in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 67, 763–773 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.07021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yogi A., Callera G.E., O’Connor S., Antunes T.T., Valinsky W., Miquel P.et al. (2013) Aldosterone signaling through transient receptor potential melastatin 7 cation channel (TRPM7) and its alpha-kinase domain. Cell. Signal. 25, 2163–2175 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Y., Yao G., Savoia C. and Touyz R.M. (2005) Transient receptor potential melastatin 7 ion channels regulate magnesium homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of angiotensin II. Circ. Res. 96, 207–215 10.1161/01.RES.0000152967.88472.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montezano A.C., Callera G.E., Yogi A., He Y., Tostes R.C., He G.et al. (2008) Aldosterone and angiotensin II synergistically stimulate migration in vascular smooth muscle cells through c-Src-regulated redox-sensitive RhoA pathways. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1511–1518 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makki N., Thiel K.W. and Miller F.J. Jr (2013) The epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligands in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 20597–20613 10.3390/ijms141020597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomas A., Futter C.E. and Eden E.R. (2014) EGF receptor trafficking: consequences for signaling and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 26–34 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin X., Polidano E., Faverdin C. and Marche P. (2005) Role of L-type calcium channel blocking in epidermal growth factor receptor-independent activation of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2. J. Hypertens. 23, 337–350 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnevale D., Facchinello N., Iodice D., Bizzotto D., Perrotta M., De Stefani D.et al. (2018) Loss of EMILIN-1 enhances arteriolar myogenic tone through TGF-beta (transforming growth factor-beta)-dependent transactivation of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) and is relevant for hypertension in mice and humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 2484–2497 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thebault S., Alexander R.T., Tiel Groenestege W.M., Hoenderop J.G. and Bindels R.J. (2009) EGF increases TRPM6 activity and surface expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 78–85 10.1681/ASN.2008030327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao H., Chen X., Du X., Guan B., Liu Y. and Zhang H. (2011) EGF enhances the migration of cancer cells by up-regulation of TRPM7. Cell Calcium 50, 559–568 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayati A., Moghimi S., Salarinejad S., Safavi M., Pouramiri B. and Foroumadi A. (2020) A review on progression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors as an efficient approach in cancer targeted therapy. Bioorg. Chem. 99, 103811 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciardiello F. and Tortora G. (2008) EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1160–1174 10.1056/NEJMra0707704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanck-Silva G., Fatori Trevizan L.N., Petrilli R., de Lima F.T., Eloy J.O. and Chorilli M. (2020) A critical review of properties and analytical/bioanalytical methods for characterization of Cetuximab. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 50, 125–135 10.1080/10408347.2019.1581984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izzedine H. and Perazella M.A. (2017) Adverse kidney effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Nephrol. Dialysis Transplant. 32, 1089–1097 10.1093/ndt/gfw467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrelli F., Borgonovo K., Cabiddu M., Ghilardi M. and Barni S. (2012) Risk of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody-related hypomagnesemia: systematic review and pooled analysis of randomized studies. Exp. Opin. Drug Saf. 11, S9–S19 10.1517/14740338.2011.606213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii H., Iihara H., Suzuki A., Kobayashi R., Matsuhashi N., Takahashi T.et al. (2016) Hypomagnesemia is a reliable predictor for efficacy of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody used in combination with first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 77, 1209–1215 10.1007/s00280-016-3039-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thangarasa T., Gotfrit J., Goodwin R.A., Tang P.A., Clemons M., Imbulgoda A.et al. (2019) Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: a survey of practice patterns among Canadian gastrointestinal medical oncologists. Curr. Oncol. 26, e162–e166 10.3747/co.26.4591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groenestege W.M., Thebault S., van der Wijst J., van den Berg D., Janssen R., Tejpar S.et al. (2007) Impaired basolateral sorting of pro-EGF causes isolated recessive renal hypomagnesemia. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2260–2267 10.1172/JCI31680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chubanov V., Ferioli S., Wisnowsky A., Simmons D.G., Leitzinger C., Einer C.et al. (2016) Epithelial magnesium transport by TRPM6 is essential for prenatal development and adult survival. eLife 5, e20914 10.7554/eLife.20914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaitsuka T., Katagiri C., Beesetty P., Nakamura K., Hourani S., Tomizawa K.et al. (2014) Inactivation of TRPM7 kinase activity does not impair its channel function in mice. Sci. Rep. 4, 5718 10.1038/srep05718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryazanova L.V., Hu Z., Suzuki S., Chubanov V., Fleig A. and Ryazanov A.G. (2014) Elucidating the role of the TRPM7 alpha-kinase: TRPM7 kinase inactivation leads to magnesium deprivation resistance phenotype in mice. Sci. Rep. 4, 7599 10.1038/srep07599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camargo L.L., Harvey A.P., Rios F.J., Tsiropoulou S., Da Silva R.N.O., Cao Z.et al. (2018) Vascular Nox (NADPH Oxidase) compartmentalization, protein hyperoxidation, and endoplasmic reticulum stress response in hypertension. Hypertension 72, 235–246 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montezano A.C., Lopes R.A., Neves K.B., Rios F. and Touyz R.M. (2017) Isolation and culture of vascular smooth muscle cells from small and large vessels. Methods Mol. Biol. 1527, 349–354 10.1007/978-1-4939-6625-7_27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chubanov V., Schafer S., Ferioli S. and Gudermann T. (2014) Natural and synthetic modulators of the TRPM7 channel. Cells 3, 1089–1101 10.3390/cells3041089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y.J., Huang W.C., Wei Y.L., Hsu S.C., Yuan P., Lin H.Y.et al. (2011) Elevated BCRP/ABCG2 expression confers acquired resistance to gefitinib in wild-type EGFR-expressing cells. PLoS ONE 6, e21428 10.1371/journal.pone.0021428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin E.Y., Lee C.S., Park M.H., Kim D.J., Kwak S.J. and Kim E.G. (2009) Involvement of betaPIX in angiotensin II-induced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 41, 387–396 10.3858/emm.2009.41.6.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stritt S., Nurden P., Favier R., Favier M., Ferioli S., Gotru S.K.et al. (2016) Defects in TRPM7 channel function deregulate thrombopoiesis through altered cellular Mg(2+) homeostasis and cytoskeletal architecture. Nat. Commun. 7, 11097 10.1038/ncomms11097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romagnani A., Vettore V., Rezzonico-Jost T., Hampe S., Rottoli E., Nadolni W.et al. (2017) TRPM7 kinase activity is essential for T cell colonization and alloreactivity in the gut. Nat. Commun. 8, 1917 10.1038/s41467-017-01960-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pijuan J., Barcelo C., Moreno D.F., Maiques O., Siso P., Marti R.M.et al. (2019) In vitro cell migration, invasion, and adhesion assays: from cell imaging to data analysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 107 10.3389/fcell.2019.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chubanov V., Waldegger S., Schnitzler M.M.y., Vitzthum H., Sassen M.C., Seyberth H.W.et al. (2004) Disruption of TRPM6/TRPM7 complex formation by a mutation in the TRPM6 gene causes hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2894–2899 10.1073/pnas.0305252101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsushita M., Kozak J.A., Shimizu Y., McLachlin D.T., Yamaguchi H., Wei F.Y.et al. (2005) Channel function is dissociated from the intrinsic kinase activity and autophosphorylation of TRPM7/ChaK1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20793–20803 10.1074/jbc.M413671200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chubanov V., Schnitzler MMy, Meissner M., Schafer S., Abstiens K., Hofmann T.et al. (2012) Natural and synthetic modulators of SK (K(ca)2) potassium channels inhibit magnesium-dependent activity of the kinase-coupled cation channel TRPM7. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 1357–1376 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01855.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q., Zhao N., Kennard S. and Lilly B. (2012) Notch2 and Notch3 function together to regulate vascular smooth muscle development. PLoS ONE 7, e37365 10.1371/journal.pone.0037365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart T.A., Azimi I., Thompson E.W., Roberts-Thomson S.J. and Monteith G.R. (2015) A role for calcium in the regulation of ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C, member 3 (ABCC3) gene expression in a model of epidermal growth factor-mediated breast cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 509–514 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schreier B., Hunerberg M., Mildenberger S., Rabe S., Bethmann D., Wickenhauser C.et al. (2018) Deletion of the EGF receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells prevents chronic angiotensin II-induced arterial wall stiffening and media thickening. Acta Physiol. 222, 0.1111/apha.12996 10.1111/apha.12996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobrydneva Y. and Blackmore P. (2001) 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate directly inhibits store-operated calcium entry channels in human platelets. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 541–552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis F.M., Azimi I., Faville R.A., Peters A.A., Jalink K., Putney J.W. Jret al. (2014) Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer cells is calcium signal dependent. Oncogene 33, 2307–2316 10.1038/onc.2013.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irtegun S., Wood R.J., Ormsby A.R., Mulhern T.D. and Hatters D.M. (2013) Tyrosine 416 is phosphorylated in the closed, repressed conformation of c-Src. PLoS ONE 8, e71035 10.1371/journal.pone.0071035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu W., Graves L.M., Gill G.N., Parsons S.J. and Samet J.M. (2002) Src-dependent phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor on tyrosine 845 is required for zinc-induced Ras activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24252–24257 10.1074/jbc.M200437200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abiria S.A., Krapivinsky G., Sah R., Santa-Cruz A.G., Chaudhuri D., Zhang J.et al. (2017) TRPM7 senses oxidative stress to release Zn(2+) from unique intracellular vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E6079–E6088 10.1073/pnas.1707380114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inoue K. and Xiong Z.G. (2009) Silencing TRPM7 promotes growth/proliferation and nitric oxide production of vascular endothelial cells via the ERK pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 83, 547–557 10.1093/cvr/cvp153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng Z., Leng T., Feng X., Sun H., Inoue K., Zhu L.et al. (2015) Silencing TRPM7 in mouse cortical astrocytes impairs cell proliferation and migration via ERK and JNK signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 10, e0119912 10.1371/journal.pone.0119912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bochaton-Piallat M.L. and Back M. (2018) Novel concepts for the role of smooth muscle cells in vascular disease: towards a new smooth muscle cell classification. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 477–480 10.1093/cvr/cvy031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.