Abstract

In 2005, the Moser group identified a new type of cell in the entorhinal cortex (ERC): the grid cell (Hafting et al., 2005). A landmark series of studies from these investigators showed that grid cells support spatial navigation by encoding position, direction as well as distance information, and they subsequently found grid cells in pre- and para-subiculum areas adjacent to the ERC (Boccara et al., 2010). Fast forward to 2010, when some clever investigators developed fMRI analysis methods to document grid-like responses in the human ERC (Doeller et al., 2010). What was not at all expected was the co-identification of grid-like fMRI responses outside of the ERC, in particular, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). Here we provide a compact overview of the burgeoning literature on grid cells in both rodent and human species, while considering the intriguing question: what are grid-like responses doing in the OFC and vmPFC?

Keywords: grid cells, spatial navigation, cognitive map, orbitofrontal cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex is critically involved in decision-making (Kaplan, Schuck, & Doeller, 2017; Rushworth et al., 2011; Schuck et al., 2016). Two prominent prefrontal areas, namely, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) (Kaplan, Schuck, & Doeller, 2017) and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (Schuck et al., 2016), have been assigned particularly important roles in these processes. Conceptual and empirical models suggest that these brain regions represent economic value (Ballesta et al., 2020; Gardner & Schoenbaum, 2020; O’Doherty et al., 2017; Padoa-Schioppa & Assad, 2006; Padoa-Schioppa & Conen, 2017), conflict (Botvinick et al., 2004), prediction error (Nobre et al., 1999; Sul et al., 2010; Tobler et al., 2006), cue-outcome associations critical for reinforcement learning (Rushworth et al., 2011), or other specific features of the current decision making process (Gardner & Schoenbaum, 2020; Schuck et al., 2016; Niv, 2019). Both OFC and vmPFC have further been ascribed roles in executive control, response inhibition, response flexibility, and the use of mental simulation to infer the value of a particular action (Howard et al., 2020; Schuck et al., 2015; Stalnaker et al., 2015; Wang, Schoenbaum, & Kahnt, 2020; Wilson et al., 2014).

Notably, many of the above-mentioned features regarding OFC and vmPFC, including executive control, behavioral flexibility, and model-based inference, are also key aspects of cognitive maps. The idea of cognitive maps was first introduced by Tolman (1948), whose seminal work focused on maze-solving in rats. Notably, while Tolman’s experimental design involved spatial learning, he argued that his experiments modeled more general features of goal-directed behavior that are crucial for a wide range of cognitive processes. In line with this proposal, O’Keefe and Nadel (1978) pointed out that the cognitive map serves as a spatio-temporal scaffold “[…] within which the items and events of an organism’s experience are located and interrelated” (p. 1). Importantly, the precise content of the map was hypothesized to vary depending on the animal’s experience: whereas rodents may populate it with objects in physical space, reptiles may use it to organize olfactory information, and humans may employ it to efficiently map semantic concepts. Thus, the cognitive map hypothesis serves as a general framework for the systematic representation of information, be it physical space (Tolman, 1948), temporal context (MacDonald et al., 2011), or abstract, conceptual knowledge (Eichenbaum, 2003).

Despite the general formulation of the term, cognitive maps were traditionally studied in the domain of spatial navigation (for review, see Behrens et al., 2018; Eichenbaum, 2015; Lisman et al., 2017), and as a consequence, equated with maps of physical space. In the context of spatial cognition, cognitive maps describe allocentric, or world-centered, representations of physical space. In other words, spatial representations of the outside world are embedded in a reference frame based on both the external environment and the objects contained within that environment. For example, when navigating to Philadelphia’s cherished sweet shop – Federal Donuts on Sansom Street – we may encode its location in relationship to other buildings and neighborhoods in Philadelphia, rather than in relationship to our own (egocentric) perspective (Wang, Chen, & Knierim, 2020). The ultimate advantage of “allocentric” vs. “egocentric” spatial strategies is the following: whereas individuals using an egocentric strategy navigate the environment based on stimulus-response associations they have recently learned, individuals using an allocentric strategy have an understanding of how different locations and objects relate to one another and thus can flexibly navigate in space by planning or inferring novel routes.

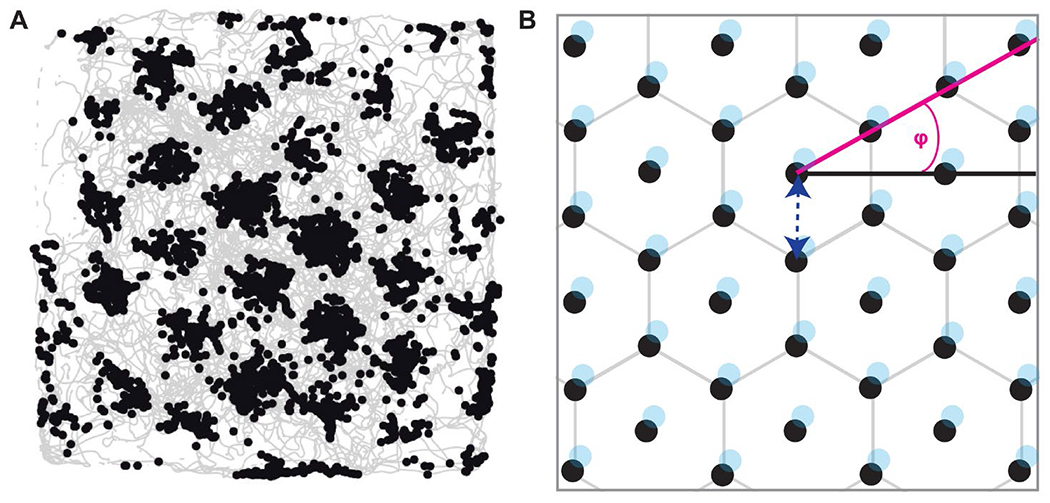

The literature suggests that two mechanisms support the formation and maintenance of cognitive maps: path integration and landmark-based navigation (Paul et al., 2009; Geva-Sagiv et al., 2015). Path integration involves the measurement of the animal’s own motion to compute its current location and orientation relative to other objects (Savelli & Knierim, 2019). Landmark-based navigation involves the recognition and utilization of familiar landmarks to monitor and, if necessary, to correct the resulting estimates (Milford et al., 2010). Importantly, the neural correlates of both mechanisms have been studied extensively in the past decades. Place cells in the hippocampus (HC) encode the current location of the animal within an environment based on distal landmarks (O’Keefe & Dostrovsky, 1971; O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). In contrast, grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex (ERC) fire at regularly spaced locations when an animal freely navigates a 2-dimensional environment, thereby providing information about position, distance, speed, and direction (Hafting et al., 2005; Rowland et al., 2016; Sargolini et al., 2006; Stensola et al., 2012; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Characteristic features of grid cells.

Note. (A) Firing locations of one example grid cell as the animal explores the arena. Animal trajectories are shown in light gray, black dots indicate the locations at which cell firing was recorded. Note that this cell has multiple receptive fields where each receptive field is surrounded by precisely 6 other receptive fields, forming the outer edges of a regular hexagon. (B) Schematic illustration of the receptive fields (shown as black dots) and the characteristic features of a grid cell. Grid orientation, or grid angle (φ), is illustrated in magenta; spacing, or wavelength, is illustrated by the dark blue, dotted arrow; phase (the location of the vertices) is illustrated in light blue.

More recent work has revisited the original idea of cognitive maps proposed by Tolman (1948), highlighting the idea that cognitive maps are not constrained to spatial landscapes, but can be employed to encode abstract (non-spatial) information about the relative magnitudes and relationships among sets of visual, olfactory, social, and imaginary concepts (Bao et al., 2019; Behrens et al., 2018; Bellmund et al., 2016; Bellmund et al., 2018; Constantinescu et al., 2016; Epstein et al, 2017; Horner et al., 2016; Julian et al., 2018; Nau et al., 2018; Park et al., 2020; Schiller et al., 2015; Tavares et al., 2015). Moreover, several authors have proposed that HC and ERC are not the only purveyors of cognitive maps, but that prefrontal brain areas, including OFC and vmPFC, also contain cognitive maps of task space (Bradfield & Hart, 2020; Eichenbaum, 2018; Schuck et al., 2018; Farovik et al., 2015; Stalnaker et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2014). This perspective provides a coherent framework for binding the multitude of functions classically associated with OFC and vmPFC into one overarching mechanism. To the extent that magnitude comparisons (for example, comparisons among stimulus values or among cached rewards) rely on accessing and exploiting the associative structure of a cognitive map, one plausible conclusion is that prefrontal regions are critical to these cognitive operations.

In support of these ideas, experimental studies have found striking evidence for grid-like responses in both OFC and vmPFC during navigation in physical (Doeller et al., 2010), conceptual (Constantinescu et al., 2016) and olfactory (Bao et al., 2019) spaces, suggesting a potential mechanistic correlate to support many different forms of cognitive maps. These findings are particularly curious as, to date, there is no evidence in the rodent literature that grid cells exist outside of the hippocampal formation (Boccara et al., 2010; Constantinescu et al., 2016), and raise questions about the exact purpose and relevance of grid-like responses in OFC and vmPFC.

We surmise that grid-like responses in the human brain occur in a wide range of areas including, but not restricted to, ERC, OFC, and vmPFC, as well as sensory regions, depending on the task at hand. That is, brain areas involved in (spatial) memory, decision-making, and sensory coding may utilize a common grid-like neural code during task performance to create cognitive maps of the current environment or the task space. This cognitive map strategy allows for the representation of relationships between different objects and/or abstract concepts, and thus optimizes behavioral outcomes. The advantages and limitations of our proposal as well as its implications for future research are discussed below.

Grid Cells in Animal Models

Grid cells were initially studied in the rodent ERC (Hafting et al., 2005; Fyhn et al., 2008), but soon discovered in other species, including bats (Yartsev et al., 2011), monkeys (Killian et al., 2012), and humans (Jacobs et al., 2013). Traditional experiments require subjects to explore an environment while neural activity in ERC is recorded. Across species, ERC neurons exhibit unique firing patterns, such that each receptive field is surrounded by exactly six other receptive fields, with six-fold symmetry, forming the vertices of a regular hexagon, and resembling a lattice of equilateral triangles (Figure 1). The resulting “grid” structure apparent in the spatial autocorrelogram lent the neurons their name. Grid cells have a number of characteristic features (Figure 1). The grid orientation, or grid angle (φ), is defined as the angle between a 0° reference line and a vector to the nearest vertex of the hexagon. The spacing, or wavelength, refers to the distance between individual receptive fields. The field size refers to the area covered by a single receptive field. Finally, the phase of the grid refers to the vertex locations. While the former three features were found to be similar at a given recording site, the latter varied considerably across neighboring cells. That is, the receptive fields of different grid cells were spatially offset so that a small population of grid cells effectively tiles the entire floor of the environment (Barry et al., 2007; Barry et al., 2012; Fyhn et al., 2007; Hafting et al., 2005; Sargolini et al., 2006; Stensola et al., 2012).

By maintaining grid spacing across different environments, grid cells can even afford the animal with the ability to perform path integration and successfully navigate a novel environment that has never been encountered before (Rowland et al., 2016). That is, using grid cells, the animal can calculate its current position based on its previous position and its past movement; or it may calculate the vector between a start position and a goal location to guide behavior (Banino et al., 2018; Bush et al., 2015). By providing a structure of space in any arbitrary environment – a feature not present in place cell firing – grid cells provide a scaffold for navigation that may not be exclusive to the ERC or to physical, spatially navigable landscapes, but may also be leveraged more widely across the brain to solve complex problems beyond the spatial domain (Behrens et al., 2018; Bellmund et al., 2018; Epstein et al., 2017; Schiller et al., 2015).

Grid-Like Responses in the Human Brain

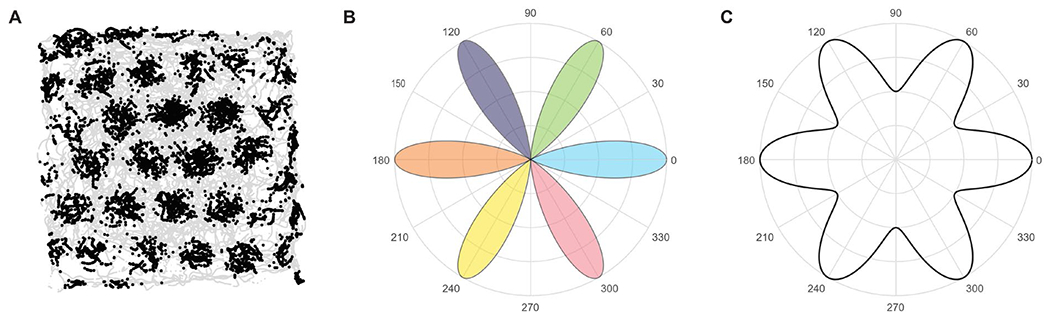

In humans, grid-like neural activity has been identified using two different methods: direct electrophysiological recordings using intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) in epilepsy patients (Jacobs et al., 2013; Nadasdy et al., 2017); and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) methods that indirectly and non-invasively capture grid-like responses in healthy individuals (Bao et al., 2019; Bellmund et al., 2016; Constantinescu et al., 2016; Doeller et al., 2010; He & Brown, 2019; Horner et al., 2016; Jacobs et al., 2013; Julian et al., 2018; Kim & Maguire, 2019; Kunz et al., 2015; Nau et al., 2018; Stangl et al., 2018). While a detailed explanation of how grid cell firing gives rise to grid-like fMRI responses is beyond the scope of this article, the basic idea is that if grid cells share a common orientation across neighboring cells (Barry et al., 2007; Doeller et al., 2010; Stensola et al., 2012; but see Keinath, 2016) and show preferential firing for movement aligned (vs. misaligned) with the main axes of the grid (Doeller et al., 2010), then one should be able to detect their presence via measures of neural population activity, such as fMRI (Doeller et al., 2010; for review, see Kriegeskorte & Storrs, 2016; Figure 2). That is, neural population activity as measured using the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal should be relatively higher on trials in which movements occurs in alignment with the six main axes of the grid.

Figure 2. Response of grid cell populations.

Note. (A) Activity of one grid cell recorded in rat ERC; black: firing locations; light gray: movement paths. (B) Schematic of the preferred firing activity of six grid cells (six different colors, e.g., the ‘pink’ cell preferentially responds when the navigator moves at an angle of 300°). All grid cells share the same grid orientation (at 60° increments), but each cell has a different preferred movement angle and will be more active when moving in that direction. (C) Summed firing rates among the six cells as a function of heading direction will elicit six-fold modulation in population activity, forming the basis for using fMRI-based techniques and analyses to identify six-fold grid-like patterns at a macroscopic scale. Figure adapted with permission from Kriegeskorte & Storrs (2016).

In line with this hypothesis, Doeller and colleagues (2010) found that when humans navigate in a virtual environment, BOLD signal in the ERC exhibited a 6-fold rotational symmetry when plotted as a function of the heading direction, consistent with the interpretation that grid cells reside in this brain region. In addition, authors reported that this effect was modulated by the speed at which participants moved in the arena, in agreement with the expected properties of grid cells (Sargolini et al., 2006). Of note, the coherence of grid orientation across voxels correlated positively with spatial memory performance. The latter finding represents a direct link between the neural grid code and behavior, in this case, performance on a spatial navigation task.

In the past decade, empirical evidence for grid-like responses in the human ERC has accumulated, with researchers using a variety of tasks and experimental settings. For example, grid-like neural responses have been observed during imagined navigation (Horner et al., 2016), mental simulation (Bellmund et al., 2016), as well as during navigation in conceptual (Constantinescu et al., 2016), visual (Julian et al., 2018; Nau et al., 2018), and olfactory space (Bao et al., 2019). In addition, reduced grid-like responses in elderly participants (Stangl et al., 2018) and in participants at risk for Alzheimer’s disease (Kunz et al., 2015) during navigation in virtual space highlight the critical role of grid-like responses for efficient spatial navigation, and perhaps cognitive abilities in general.

Grid-Like Responses Beyond Entorhinal Cortex

Of note, while many of the above studies focused their region of interest on ERC, some extended their analyses to the whole brain and reported grid-like responses in a wide range of areas, including, but not limited to, the ERC. Grid-like responses have been identified in OFC (Constantinescu et al., 2016), vmPFC (Bao et al., 2019; Constantinescu et al., 2016; Doeller et al., 2010), and anterior cingulate cortex (Jacobs et al., 2013). These results are of particular interest considering that, to the best of our knowledge, there is no report, let alone any systematic investigation, of grid cells outside of the hippocampal formation in the rodent literature (Boccara et al., 2010; Constantinescu et al., 2016), despite the suggestion of a corresponding experiment 10 years ago (Doeller et al., 2010). We are thus left with the curious question: why are grid-like fMRI responses found outside of ERC?

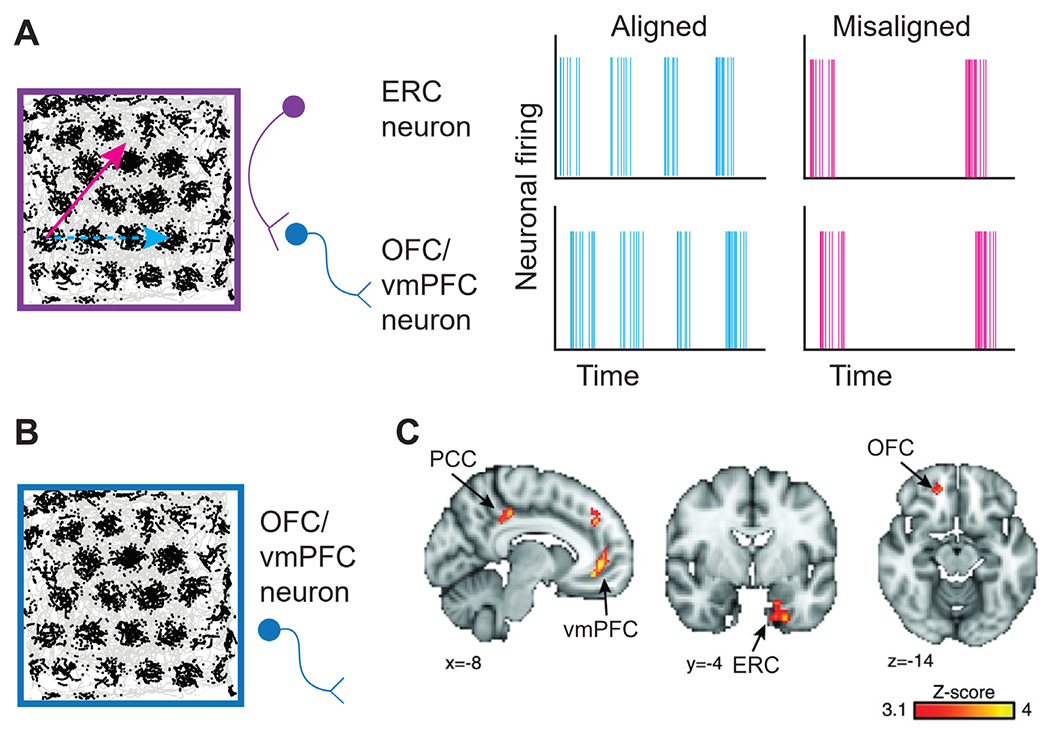

Considering the lack of support for grid cells outside of the ERC in rodents, we favor an altogether different hypothesis to explain the detection of human grid-like fMRI responses in other brain regions. During any type of navigational task – which may encompass conceptual, physical (virtual), imagined, or perceptual spaces – when the navigator is moving in line with the preferred grid cell angle (at six-fold symmetry), downstream projections from the ERC to target areas in OFC or vmPFC will be more strongly activated, compared to when the navigator is moving off-axis to the preferred grid angle. The important point is that because downstream activity in OFC or vmPFC will be higher at every 60° increment of the preferred grid angle, it is tempting to conclude that there must be veridical grid cells in these regions, when in fact this activity pattern is simply the result of incoming input from ERC (Bao et al., 2019; Figure 3). One advantage of such connectivity is that the ERC is well-positioned to influence goal-directed behavior more broadly. For example, information about trajectories in physical or abstract space could be integrated with cue-outcome associations in the OFC and vmPFC to maximize reward, or with sensory object representations to enhance perceptual processing. Of course, the existence of such mechanisms does not negate the possibility that veridical grid cells reside in areas outside of human ERC (Jacobs et al., 2013), and it might be the case that different mechanisms help shape different forms of navigation-based behavior.

Figure 3. Origins of grid-like responses in OFC and vmPFC.

Note. (A) Grid-like responses in OFC and vmPFC detected using fMRI could arise as the result of grid cell activity in ERC. The purple grid cell shows greater spiking activity as movement occurs in alignment with the main axes of the grid (light blue trajectory) compared to when movement occurs misaligned with the main axes of the grid (magenta trajectory). The resulting activity elicits relatively higher activity (light blue trajectory) or lower activity (magenta trajectory) in OFC and vmPFC neurons (dark blue), respectively, that receive centrifugal input from ERC. Thus, activity in OFC and vmPFC will be modulated as a function of movement trajectory, despite the absence of actual grid cells in these areas. (B) Grid-like responses in OFC and vmPFC detected using fMRI could arise directly due to the presence of veridical grid cells in the OFC and vmPFC. (C) Evidence for grid-like responses in a network of brain regions, including ERC, vmPFC, and OFC, as reported in Constantinescu et al. (2016). PCC (posterior cingulate cortex). Figure adapted with permission from Constantinescu et al. (2016).

Interestingly, Doeller and colleagues (2010) were the first to propose the idea that grid cells are present in an entire network of brain regions, extending far beyond the ERC. While the authors admitted that neural representations with 6-fold rotational symmetry were weaker in brain regions outside of the ERC, they suggested that grid cells may be present in these areas, albeit at a lower density. However, given that only about 10%-20% of the neurons in rodent ERC are grid cells (Diehl et al., 2017; Kropff et al., 2015), it is unlikely that areas with even lower ratios of grid cell populations would produce a macroscopically visible, neural signal (Kunz et al., 2019). In addition, Jacobs and colleagues (2013) reported that 14% of the cells recorded in human ERC, and 12% of the neurons recorded in frontal brain areas, including the anterior cingulate cortex, exhibited grid cell-like firing, suggesting that ratios are comparable across brain regions. Such data clearly highlight the need for more targeted studies on grid-like features in non-ERC areas.

On the other hand, presuming that grid cells are indeed present in OFC and vmPFC (Figure 3), it is important to identify their role(s) in behavior. Experimental studies identified a potential role of prefrontal areas in human path integration (Wolbers et al., 2007), as well as spatial planning and decision making (Ekstrom et al., 2017; Kaplan, King, Koster, et al., 2017). If OFC and vmPFC indeed support spatial working memory, as suggested by some authors (Wolbers et al., 2007), then grid cells within these regions could directly help track distance, direction, and speed to adjust trajectories on demand. Cognitive maps supported by grid cells in OFC and vmPFC may represent a separate instantiation of the cognitive map in ERC, retrieved from memory and updated based on current task contingencies and behavioral goals. However, confirmatory evidence from animal models is currently difficult to establish, given that animal studies provide no evidence for or against grid cells in OFC, vmPFC, or other brain regions.

A different idea, extending beyond the domain of spatial navigation, comes from research indicating that OFC and vmPFC represent the position in a state space of a particular task (Kaplan, Schuck, & Doeller, 2017; Behrens et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2016). That is, OFC and vmPFC may store information about the current state in a task, as well as the transitions between various task states, to inform decision-making (Stalnaker et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2014). Thus, grid-like responses in the very same areas could represent the associative structure of a given task, representing relationships between non-spatial concepts (Behrens et al., 2018). This hypothesis is in line with the idea that cognitive maps, and in particular grid-like codes, may serve as a universal mechanism to represent relationships between various spatial and non-spatial landscapes, or between concrete and abstract concepts (Epstein et al., 2017; Behrens et al., 2018; Bellmund et al, 2018; Kaplan, Schuck, & Doeller, 2017; Schiller et al., 2015), in order to enhance cognitive and perceptual processing. The corresponding cognitive processes may be mediated by a multitude of areas adopting a grid-like code to represent relationships between stimuli and concepts in a specific cognitive space.

While the presence of cognitive maps of task space in OFC and vmPFC has been suggested in both animal (Bradfield & Hart, 2020; Lopatina et al., 2017; Zhou, Gardner, Stalnaker, et al., 2019; Zhou, Montesinos-Cartagena, Wikenheiser, et al., 2019) and human (Howard & Kahnt, 2017; Schuck et al., 2016; Schuck & Niv, 2019) studies, there is little evidence for hexagonally oriented map-like representations that encode distance and direction in these specific brain areas. This “absence of evidence” (for grid-like responses) may partially be due to the fact that many of the tasks used in the above studies lack a clear metric structure. For example, reinforcement paradigms often switch between different task states in a particular sequence, but the underlying task structure does not define how individual elements, especially if they are non-neighboring, are arranged relative to one another. In addition, it is not apparent how novel ‘routes’ can be planned given that tasks are defined as a fixed sequence of events.

However, a recent fMRI study performed in human participants found representations of Euclidean distance in OFC and vmPFC during navigation in social space (Park et al., 2020). In this task, participants had to make comparisons between individuals of varying popularity and competence. Unbeknownst to the participants, these two properties spanned the two dimensions of a social space in which different individuals could be organized based on their popularity and competence. By comparing different individuals, participants effectively defined trajectories in social space which in turn were reflected in neural activity. Of note, Euclidean distance between compared individuals was tracked in OFC and vmPFC, suggesting a two-dimensional representation of social space. While these findings clearly favor a map-like representation of the cognitive task space, the authors found no evidence for representations of trajectory angle, and did not directly test for the presence of grid-like responses in the candidate brain regions, thus limiting conclusions.

An interesting observation is the fact that OFC and vmPFC are often found to represent “hidden” states, that is, states that cannot be directly observed based on the environmental features present in a given situation, but need to be inferred based on the history and/or past experiences with the task (Schuck et al., 2016; Stalnaker et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2014). Thus, the cognitive map present in the OFC and vmPFC may be somewhat removed from immediate sensory representations (Behrens et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2016), and thus more easily generalized to different sensory environments or tasks. Such flexibly adaptive representations may be useful for guiding goal-directed decisions. While it has recently been suggested that grid cells provide the key properties to assemble such representations (Behrens et al., 2018), another study suggested that grid-like responses also occur in olfactory sensory areas (Bao et al., 2019). Bao and colleagues (2019) asked participants to navigate in a 2-dimensional perceptual space comprised of odors and found evidence for grid-like responses in ERC, vmPFC, and the anterior piriform cortex. This finding is of particular interest, because it implies that olfactory navigation – as opposed to navigation in visual, imagined, or social space – engages a grid-like code in olfactory areas. While the precise function of olfactory grid cells remains to be determined, this finding suggests that grid cells can represent a cognitive map of modality-specific, rather than modality-free (or abstract), task space. At the very least, the specific sensory environment may play a role in determining which areas are recruited into the broader grid network.

Conundrums and Conclusions

We conclude by noting that all of the above hypotheses lack one essential piece of information. Unless grid cells can be directly detected in OFC and vmPFC, the potential role or purpose of indirectly recorded grid-like responses in these areas remains speculative. As pointed out, grid-like responses in OFC and vmPFC may arise based on neural signals from ERC, but this does not necessarily imply that grid cells are inherent to OFC and vmPFC. That is, grid-like responses in areas outside of the ERC may represent downstream patterning of grid cell activity arising in ERC. In this way ERC could flexibly recruit brain regions into the grid network in a task-dependent manner. On the other hand, the presence of veridical grid cells in OFC and vmPFC could confer neural processing advantages in supporting cognitive maps of abstract, and/or modality-specific task space to guide decision-making, while working in tandem with grid-like responses in ERC to guide action and behavior more strategically.

In animal models, the current evidence fails to support either of these two hypotheses: on the one hand, there is no evidence of entorhinal grid cells modulating activity in downstream areas in a grid-like manner, and on the other hand, there are no reports of grid cells in areas outside of the hippocampal formation. Considering that rodent studies commonly measure neural activity in a variety of brain regions (Wang, Boboila, Chin, et al., 2020; Wikenheiser & Schoenbaum, 2016; Zhou, Gardner, Stalnaker, et al., 2019; Zhou, Montesinos-Cartagena, Wikenheiser, et al., 2019; to name just a few), one might expect that in-situ grid cells in OFC or vmPFC, or grid-like activity being driven by ERC, would become apparent in the neural data, if truly relevant for behavior, even if none of these investigations was studying the phenomenon from the outset. The absence of a corresponding neural signature may imply that different organizational schemes are more perhaps more prominent in these extra-ERC areas. For example, topographic representations of information may dominate neural coding in primary sensory (e.g., visual, auditory, and somatosensory) cortices, making it more difficult to capture grid-like responses in these areas. Note that this idea is not necessarily at odds with the notion of grid-like responses in the piriform cortex as demonstrated in humans (Bao et al., 2019), as the piriform cortex has traditionally been described as an area comprising multiple features typical of an association cortex (Gottfried, 2010).

On the other hand, it is plausible that grid-like responses only emerge under certain behavioral demands, or under certain environmental conditions. Consider the discovery of grid cells (for review, see Rowland et al., 2016): Moser and colleagues were initially unable to explain the firing pattern of grid cells in ERC as they measured the neural activity of the cells in too small of an environment. When expanding the arena, the six-fold periodicity in the neural signal of grid cells became apparent. Likewise, grid-like responses in sensory, or prefrontal areas may only become apparent when the task space is large, or complex, enough to capture grid-like responses. This idea may also offer a potential explanation as to why grid-like responses in these regions have not been identified in the animal literature, as tasks used in non-human subjects are typically simpler and contain fewer relationships between stimuli than those employed in studies with human subjects.

To refine these ideas, it will be important to design experiments in both animal and human species that challenge the current views and test for the presence of grid cells in a multitude of different tasks and across the entire brain. For example, studies performed in rodents should measure single-unit activity and the local field potential in a variety of brain regions (including ERC, OFC, and vmPFC) during the performance of a complex or abstract task to assess the presence of grid cells and grid-like responses, respectively. Such a systematic investigation could test these different hypotheses providing valuable insights into the behavioral relevance of grid cells across species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant funding awarded to Jay A. Gottfried from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01DC010014).

Footnotes

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Ballesta S, Shi W, Conen KE, & Padoa-Schioppa C (2020). Values Encoded in Orbitofrontal Cortex Are Causally Related to Economic Choices. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2020.03.10.984021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banino A, Barry C, Uria B, Blundell C, Lillicrap T, Mirowski P, Pritzel A, Chadwick MJ, Degris T, Modayil J, Wayne G Soyer H, Viola F, Zhang B, Goroshin R, Rabinowitz N, Pascanu R, Beattie C, Petersen S, Sadik A, Gaffney S King H, Kavukcuoglu K, Hassabis D, Hadsell R, & Kumaran D (2018). Vector-based navigation using grid-like representations in artificial agents. Nature, 557(7705), 429–433. 10.1038/s41586-018-0102-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Gjorgieva E, Shanahan LK, Howard JD, Kahnt T, & Gottfried JA (2019). Grid-like neural representations support olfactory navigation of a two-dimensional odor space. Neuron, 102(5), 1066–1075. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Hayman R, Burgess N, & Jeffery KJ (2007). Experience-dependent rescaling of entorhinal grids. Nature Neuroscience, 10(6), 682–684. 10.1038/nn1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Ginzberg LL, O’Keefe J, & Burgess N (2012). Grid cell firing patterns signal environmental novelty by expansion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(43), 17687–17692. 10.1073/pnas.1209918109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield LA, & Hart G (2020). Rodent medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortices represent unique components of cognitive maps of task space. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 108, 287–294. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Muller TH, Whittington JC, Mark S, Baram AB, Stachenfeld KL, & Kurth-Nelson Z (2018). What is a cognitive map? Organizing knowledge for flexible behavior. Neuron, 100(2), 490–509. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmund JL, Deuker L, Schröder TN, & Doeller CF (2016). Grid-cell representations in mental simulation. Elife, 5, e17089. 10.7554/eLife.17089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmund JL, Gärdenfors P, Moser EI, & Doeller CF (2018). Navigating cognition: Spatial codes for human thinking. Science, 362(6415). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccara CN, Sargolini F, Thoresen VH, Solstad T, Witter MP, Moser EI, & Moser MB (2010). Grid cells in pre-and parasubiculum. Nature Neuroscience, 13(8), 987–994. 10.1038/nn.2602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, & Carter CS (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(12), 539–546. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush D, Barry C, Manson D, & Burgess N (2015). Using grid cells for navigation. Neuron, 87(3), 507–520. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu AO, O’Reilly JX, & Behrens TE (2016). Organizing conceptual knowledge in humans with a gridlike code. Science, 352(6292), 1464–1468. 10.1126/science.aaf0941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl GW, Hon OJ, Leutgeb S, & Leutgeb JK (2017). Grid and nongrid cells in medial entorhinal cortex represent spatial location and environmental features with complementary coding schemes. Neuron, 94(1), 83–92. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doeller CF, Barry C, & Burgess N (2010). Evidence for grid cells in a human memory network. Nature, 463(7281), 657–661. 10.1038/nature08704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H (2018). Barlow versus Hebb: When is it time to abandon the notion of feature detectors and adopt the cell assembly as the unit of cognition?. Neuroscience Letters, 680, 88–93. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H (2015). The hippocampus as a cognitive map… of social space. Neuron, 87(1), 9–11. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H (2003). The hippocampus, episodic memory, declarative memory, spatial memory… where does it all come together?. International Congress Series (1250, 235–244). 10.1016/S0531-5131(03)00183-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom AD, Huffman DJ, & Starrett M (2017). Interacting networks of brain regions underlie human spatial navigation: a review and novel synthesis of the literature. Journal of Neurophysiology, 118(6), 3328–3344. 10.1152/jn.00531.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RA, Patai EZ, Julian JB, & Spiers HJ (2017). The cognitive map in humans: spatial navigation and beyond. Nature Neuroscience, 20(11), 1504–1513. 10.1038/nn.4656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farovik A, Place RJ, McKenzie S, Porter B, Munro CE, & Eichenbaum H (2015). Orbitofrontal cortex encodes memories within value-based schemas and represents contexts that guide memory retrieval. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(21), 8333–8344. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0134-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Hafting T, Treves A, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2007). Hippocampal remapping and grid realignment in entorhinal cortex. Nature, 446(7132), 190–194. 10.1038/nature05601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Hafting T, Witter MP, Moser EI, & Moser MB (2008). Grid cells in mice. Hippocampus, 18(12), 1230–1238. 10.1002/hipo.20472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MP, & Schoenbaum G (2020). The orbitofrontal cartographer. Psyarxiv. 10.31234/osf.io/4mrxy [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva-Sagiv M, Las L, Yovel Y, & Ulanovsky N (2015). Spatial cognition in bats and rats: from sensory acquisition to multiscale maps and navigation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(2), 94–108. 10.1038/nrn3888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA (2010). Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(9), 628–641. 10.1038/nrn2883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T, Fyhn M, Molden S, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2005). Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature, 436(7052), 801–806. 10.1038/nature03721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, & Brown TI (2019). Environmental barriers disrupt grid-like representations in humans during navigation. Current Biology, 29(16), 2718–2722. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner AJ, Bisby JA, Zotow E, Bush D, & Burgess N (2016). Grid-like processing of imagined navigation. Current Biology, 26(6), 842–847. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JD, & Kahnt T (2017). Identity-specific reward representations in orbitofrontal cortex are modulated by selective devaluation. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(10), 2627–2638. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3473-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JD, Reynolds R, Smith DE, Voss JL, Schoenbaum G, & Kahnt T (2020). Targeted stimulation of human orbitofrontal networks disrupts outcome-guided behavior. Current Biology, 30(3), 490–498. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Weidemann CT, Miller JF, Solway A, Burke JF, Wei XX, Suthana N, Sperling MR, Sharan AD, Fried I, & Kahana MJ (2013). Direct recordings of grid-like neuronal activity in human spatial navigation. Nature Neuroscience, 16(9), 1188–1190. 10.1038/nn.3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian JB, Keinath AT, Frazzetta G, & Epstein RA (2018). Human entorhinal cortex represents visual space using a boundary-anchored grid. Nature Neuroscience, 21(2), 191–194. 10.1038/s41593-017-0049-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R, King J, Koster R, Penny WD, Burgess N, & Friston KJ (2017). The neural representation of prospective choice during spatial planning and decisions. PLOS Biology, 15(1), e1002588. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R, Schuck NW, & Doeller CF (2017). The role of mental maps in decision-making. Trends in Neurosciences, 40(5), 256–259. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinath AT (2016). The preferred directions of conjunctive grid X head direction cells in the medial entorhinal cortex are periodically organized. PLOS One, 11(3), e0152041. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian NJ, Jutras MJ, & Buffalo EA (2012). A map of visual space in the primate entorhinal cortex. Nature, 491(7426), 761–764. 10.1038/nature11587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, & Maguire EA (2019). Can we study 3D grid codes non-invasively in the human brain? Methodological considerations and fMRI findings. NeuroImage, 186, 667–678. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropff E, Carmichael JE, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2015). Speed cells in the medial entorhinal cortex. Nature, 523(7561), 419–424. 10.1038/nature14622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz L, Maidenbaum S, Chen D, Wang L, Jacobs J, & Axmacher N (2019). Mesoscopic neural representations in spatial navigation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(7), 615–630. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz L, Schröder TN, Lee H, Montag C, Lachmann B, Sariyska R, Reuter M, Stirnberg R, Stöcker T, Messing-Floeter PC, Fell J, Doeller CF, Axmacher N (2015). Reduced grid-cell—like representations in adults at genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Science, 350(6259), 430–433. 10.1126/science.aac8128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, & Storrs KR (2016). Grid cells for conceptual spaces?. Neuron, 92(2), 280–284. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, Buzsáki G, Eichenbaum H, Nadel L, Ranganath C, & Redish AD (2017). Viewpoints: how the hippocampus contributes to memory, navigation and cognition. Nature Neuroscience, 20(11), 1434–1447. 10.1038/nn.4661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatina N, Sadacca BF, McDannald MA, Styer CV, Peterson JF, Cheer JF, & Schoenbaum G (2017). Ensembles in medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex construct cognitive maps emphasizing different features of the behavioral landscape. Behavioral Neuroscience, 131(3), 201. 10.1037/bne0000195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald CJ, Lepage KQ, Eden UT, & Eichenbaum H (2011). Hippocampal “time cells” bridge the gap in memory for discontiguous events. Neuron, 71(4), 737–749. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milford MJ, Wiles J, & Wyeth GF (2010). Solving navigational uncertainty using grid cells on robots. PLOS Computational Biology, 6(11), e1000995. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadasdy Z, Nguyen TP, Török Á, Shen JY, Briggs DE, Modur PN, & Buchanan RJ (2017). Context-dependent spatially periodic activity in the human entorhinal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(17), E3516–E3525. 10.1073/pnas.1701352114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau M, Schröder TN, Bellmund JL, & Doeller CF (2018). Hexadirectional coding of visual space in human entorhinal cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 21(2), 188–190. 10.1038/s41593-017-0050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv Y (2019). Learning task-state representations. Nature Neuroscience, 22(10), 1544–1553. 10.1038/s41593-019-0470-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Coull JT, Frith CD, & Mesulam MM (1999). Orbitofrontal cortex is activated during breaches of expectation in tasks of visual attention. Nature Neuroscience, 2(1), 11–12. 10.1038/4513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Cockburn J, & Pauli WM (2017). Learning, reward, and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 73–100. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, & Nadel L (1978). The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, & Dostrovsky J (1971). The hippocampus as a spatial map: Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Research, 34, 171–175. 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoa-Schioppa C, & Assad JA (2006). Neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex encode economic value. Nature, 441(7090), 223–226. 10.1038/nature04676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoa-Schioppa C, & Conen KE (2017). Orbitofrontal cortex: a neural circuit for economic decisions. Neuron, 96(4), 736–754. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SA, Miller DS, Nili H, Ranganath C, & Boorman ED (2020). Map making: constructing, combining and inferring on abstract cognitive maps. Neuron, 107(6), 1226–1238. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul CM, Magda G, & Abel S (2009). Spatial memory: Theoretical basis and comparative review on experimental methods in rodents. Behavioural Brain Research, 203(2), 151–164. 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland DC, Roudi Y, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2016). Ten years of grid cells. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 39, 19–40. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth MF, Noonan MP, Boorman ED, Walton ME, & Behrens TE (2011). Frontal cortex and reward-guided learning and decision-making. Neuron, 70(6), 1054–1069. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargolini F, Fyhn M, Hafting T, McNaughton BL, Witter MP, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2006). Conjunctive representation of position, direction, and velocity in entorhinal cortex. Science, 312(5774), 758–762. 10.1126/science.1125572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelli F, & Knierim JJ (2019). Origin and role of path integration in the cognitive representations of the hippocampus: computational insights into open questions. Journal of Experimental Biology, 222 (Suppl 1). 10.1242/jeb.188912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller D, Eichenbaum H, Buffalo EA, Davachi L, Foster DJ, Leutgeb S, & Ranganath C (2015). Memory and space: towards an understanding of the cognitive map. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(41), 13904–13911. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2618-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck NW, Cai MB, Wilson RC, & Niv Y (2016). Human orbitofrontal cortex represents a cognitive map of state space. Neuron, 91(6), 1402–1412. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck NW, Gaschler R, Wenke D, Heinzle J, Frensch PA, Haynes JD, & Reverberi C (2015). Medial prefrontal cortex predicts internally driven strategy shifts. Neuron, 86(1), 331–340. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck NW, & Niv Y (2019). Sequential replay of nonspatial task states in the human hippocampus. Science, 364(6447). 10.1126/science.aaw5181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck NW, Wilson R, & Niv Y (2018). A state representation for reinforcement learning and decision-making in the orbitofrontal cortex. In Morris R, Bornstein A, Shenhav A (Eds.), Goal-directed decision making (pp. 259–278). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-812098-9.00012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker TA, Cooch NK, & Schoenbaum G (2015). What the orbitofrontal cortex does not do. Nature Neuroscience, 18(5), 620. 10.1038/nn.3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl M, Achtzehn J, Huber K, Dietrich C, Tempelmann C, & Wolbers T (2018). Compromised grid-cell-like representations in old age as a key mechanism to explain age-related navigational deficits. Current Biology, 28(7), 1108–1115. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensola H, Stensola T, Solstad T, Frøland K, Moser MB, & Moser EI (2012). The entorhinal grid map is discretized. Nature, 492, 72–78. 10.1038/nature11649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sul JH, Kim H, Huh N, Lee D, & Jung MW (2010). Distinct roles of rodent orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortex in decision making. Neuron, 66(3), 449–460. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares RM, Mendelsohn A, Grossman Y, Williams CH, Shapiro M, Trope Y, & Schiller D (2015). A map for social navigation in the human brain. Neuron, 87(1), 231–243. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler PN, O’Doherty JP, Dolan RJ, & Schultz W (2006). Human neural learning depends on reward prediction errors in the blocking paradigm. Journal of Neurophysiology, 95(1), 301–310. 10.1152/jn.00762.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EC (1948). Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological Review, 55(4), 189–208. 10.1037/h0061626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PY, Boboila C, Chin M, Higashi-Howard A, Shamash P, Wu Z, Stein NP, Abbott LF, & Axel R (2020). Transient and persistent representations of odor value in prefrontal cortex. Neuron, 108(1), 209–224. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Chen X, & Knierim JJ (2020). Egocentric and allocentric representations of space in the rodent brain. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 60, 12–20. 10.1016/j.conb.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Schoenbaum G, & Kahnt T (2020). Interactions between human orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus support model-based inference. PLOS Biology, 18(1), e3000578. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikenheiser AM, & Schoenbaum G (2016). Over the river, through the woods: cognitive maps in the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(8), 513–523. 10.1038/nrn.2016.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RC, Takahashi YK, Schoenbaum G, & Niv Y (2014). Orbitofrontal cortex as a cognitive map of task space. Neuron, 81(2), 267–279. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolbers T, Wiener JM, Mallot HA, & Büchel C (2007). Differential recruitment of the hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex, and the human motion complex during path integration in humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(35), 9408–9416. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2146-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yartsev MM, Witter MP, & Ulanovsky N (2011). Grid cells without theta oscillations in the entorhinal cortex of bats. Nature, 479(7371), 103–107. 10.1038/nature10583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Gardner MP, Stalnaker TA, Ramus SJ, Wikenheiser AM, Niv Y, & Schoenbaum G (2019). Rat orbitofrontal ensemble activity contains multiplexed but dissociable representations of value and task structure in an odor sequence task. Current Biology, 29(6), 897–907. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Montesinos-Cartagena M, Wikenheiser AM, Gardner MP, Niv Y, & Schoenbaum G (2019). Complementary task structure representations in hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex during an odor sequence task. Current Biology, 29(20), 3402–3409. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]