Key Points

Question

What are the risks of viral aerosolization and ways to minimize exposure during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care?

Findings

In this comparative effectiveness study using animal and manikin trials, tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care (cough, airway humidification, and suctioning of the tracheostomy) produced significant respirable aerosolized particles above baseline. The combination of a heat moisture exchanger and surgical mask was the most effective covering to reduce aerosolized particle exposure from a tracheostomy.

Meaning

Tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care generate substantial aerosols, but a combination of heat moisture exchanger and surgical mask coverage of the tracheostomy was associated with a significant decrease in the risk of viral transmission to health care workers.

Abstract

Importance

During respiratory disease outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, aerosol-generating procedures, including tracheostomy, are associated with the risk of viral transmission to health care workers.

Objective

To quantify particle aerosolization during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care and to evaluate interventions that minimize the risk of viral particle exposure.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This comparative effectiveness study was conducted from August 2020 to January 2021 at a tertiary care academic institution. Aerosol generation was measured in real time with an optical particle counter during simulated (manikin) tracheostomy surgical and clinical conditions, including cough, airway nebulization, open suctioning, and electrocautery. Aerosol sampling was also performed during in vivo swine tracheostomy procedures (n = 4), with or without electrocautery. Fluorescent dye was used to visualize cough spread onto the surgical field during swine tracheostomy. Finally, 6 tracheostomy coverings were compared with no tracheostomy covering to quantify reduction in particle aerosolization.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Respirable aerosolized particle concentration.

Results

Cough, airway humidification, open suctioning, and electrocautery produced aerosol particles substantially above baseline. Compared with uncovered tracheostomy, decreased aerosolization was found with the use of tracheostomy coverings, including a cotton mask (73.8% [(95% CI, 63.0%-84.5%]; d = 3.8), polyester gaiter 79.5% [95% CI, 68.7%-90.3%]; d = 7.2), humidification mask (82.8% [95% CI, 72.0%-93.7%]; d = 8.6), heat moisture exchanger (HME) (91.0% [95% CI, 80.2%-101.7%]; d = 19.0), and surgical mask (89.9% [95% CI, 79.3%-100.6%]; d = 12.8). Simultaneous use of a surgical mask and HME decreased the particle concentration compared with either the HME (95% CI, 1.6%-12.3%; Cohen d = 1.2) or surgical mask (95% CI, 2.7%-13.2%; d = 1.9) used independently. Procedures performed with electrocautery increased total aerosolized particles by 1500 particles/m3 per 5-second interval (95% CI, 1380-1610 particles/m3 per 5-second interval; d = 1.8).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this laboratory and animal comparative effectiveness study indicate that tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care are associated with significant aerosol generation, putting health care workers at risk for viral transmission of airborne diseases. Combined HME and surgical mask coverage of the tracheostomy was associated with decreased aerosolization, thereby reducing the risk of viral transmission to health care workers.

This comparative effectiveness study quantifies particle aerosolization and compares the effectiveness of 5 types of tracheostomy coverings to minimize the risk of particle exposure during tracheostomy surgery and care.

Introduction

Protecting health care workers from nosocomial viral transmission is critical while treating patients with respiratory infections. In particular, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplet and aerosolization spread of viral-laden particles through close-range person-to-person contact.1,2 Studies have shown that speaking and coughing produce a mixture of droplets and aerosol particles (<5-10 μm in diameter) that are capable of remaining suspended in the environment for hours.3 The RNA for SARS-CoV-2, which is approximately 0.1 μm in diameter, has been recovered from air samples in hospitals, where rooms with poor ventilation prolong airborne time of infectious aerosols.4 Therefore, aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) pose risks of viral transmission to health care workers performing those procedures, as well as to nearby hospital staff and any present family members.5

Airway surgery, including tracheostomy, and tracheostomy suction and cleaning are AGPs that pose risks to otolaryngologists, other surgeons who perform tracheostomy, and critical care physicians, nurses, and health care workers owing to high concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 in upper airway secretions.6,7,8 Tracheostomy is especially pertinent to SARS-CoV-2 infection because patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19 often require prolonged intubation and subsequent tracheostomy to reduce the risk of laryngotracheal injury. A systematic review ranked tracheostomy as the second highest risk AGP, just behind tracheal intubation.9 In a separate case-control study,10 health care workers who performed tracheotomy during the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic were 4.15 times as likely to contract the virus than those who did not perform tracheotomy. Furthermore, patients with a tracheostomy may be infectious for a longer period of time owing to delayed clearance of viral RNA in critically ill patients.11 In addition to surgical risks, viral aerosolization may also occur during tracheostomy care after weaning from the ventilator during bronchoscopies, suctioning and dressing changes, and patient cough.12 In patients with COVID-19 or patients under investigation who require tracheostomy, it is critical to prevent and reduce aerosol spread that puts the health care team at risk.

Many recommendations have been proposed to minimize aerosol transmission. Proof-of-concept enclosures have been designed to reduce aerosolization during surgery.13,14,15,16 Betancourt-Ramirez et al17 suggested a percutaneous tracheostomy technique to minimize aerosolization in which mechanical ventilation is stopped until tracheostomy tube insertion and balloon inflation. During ventilation and weaning, closed circuit ventilation systems have also been proposed to reduce aerosolization from patients with a tracheostomy.18 However, those studies do not quantify or show a reduction in aerosolized particles with the proposed interventions. Other studies have measured viral particle aerosolization during intubation or extubation,19,20 bronchoscopy,20,21 and other potential AGPs,22,23,24 but none of the studies quantify aerosolization during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care.

This comparative effectiveness study aimed to measure aerosolized particle generation during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care (suction, nebulization, and cough). It was hypothesized that tracheostomy coverings, including heat moisture exchangers (HMEs) and masks, would reduce aerosol particle generation and would be highly effective strategies to reduce aerosol exposure of health care workers. Aerosol generation was evaluated during swine tracheostomy surgery to identify the high aerosol generating periods of the procedure and to assess aerosol concentrations relative to the positions of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and operating room staff. This work will inform strategies to reduce viral spread during care of patients requiring tracheostomy.

Methods

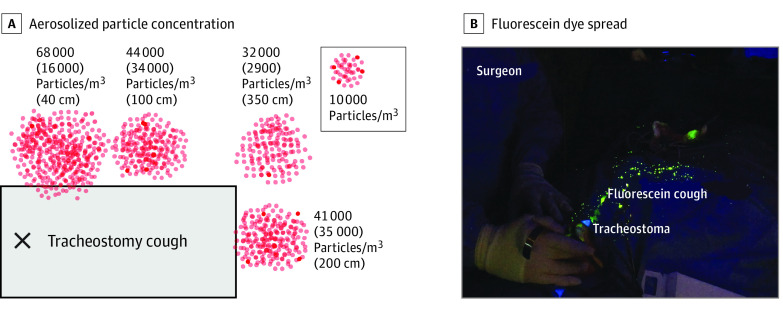

Aerosol Sampling

Aerosol particle sampling was performed using an optical particle counter (OPC) (Nanozen DustCount 9000) to measure particle concentration and size distribution of respirable particles with a diameter smaller than 4 μm (Figure 1). In occupational health, respirable particles (ie, particles with aerodynamic diameter <4 µm) are defined as the fraction of inhaled particles capable of penetrating beyond the ciliated airways.25,26,27 The OPC uses a flow rate of 1 L/min, with measurements occurring every 5 seconds, measuring particles in 6 distinct size bins. Experimental particle counts were normalized to 2-minute background baseline readings in a simulated operating room at the start of each session prior to simulated patient care activities. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Johns Hopkins University and followed the Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Figure 1. Aerosol Measurement During Tracheostomy Surgery and Care.

Annotated cube represents the optical particle counter units in number of particles per cubic meter of air.

Swine Tracheostomy Procedure and Cough Measurement

Aerosolized particles were measured during tracheostomy procedures performed in swine. Operating surgeons maintained full personal protective equipment, including a head cover, gown, gloves, face shield, surgical mask, and eye protection. The OPC was positioned at a surgeon’s approximate head height (1.5 m) horizontally 80 cm from the pig’s airway. Key surgical events were recorded, including skin incision, tracheal incision, tracheostomy tube insertion, and tracheostomy tube securement. Two surgical procedures were performed using electrocautery, and 2 surgical procedures were performed with cold instrumentation. After tracheostomy placement, an artificial cough from the pig tracheostoma was performed with 1 to 2 mL of fluorescent dye solution (25 mg of fluorescein in 10 mL of water) to visualize fluorescence spread on the surgical field and the associated risk to health care workers present during surgery.

Tracheostomy Care: Cough, Suction, and Nebulization Measurements

Cough simulation was repeated using a tracheostomy manikin to measure particle concentration at various health care worker positions in a patient room, with the OPC at approximate head level (1.5 m). Cough was simulated to generate aerosolization of 1 to 2 mL of saline by injecting 60 mL of air into a tracheostomy tube with the distal end occluded to allow for particle emission through the stoma. This was repeated 6 times for 30 seconds each time (average flow rate of 18 L/min per cough, with peak flow at approximately 36 L/min), which was modeled after cough flow rates measured in hospitalized patients.28 With the OPC at a 30-cm vertical distance from the tracheostomy, particle concentration was also measured during 30 seconds of tracheostomy open suctioning, uncovered nebulization with a humidification mask (CareFusion; AirLife), and nebulization with a surgical mask.

Mask Evaluation

Tracheostomy mask coverings, including tracheal humidification mask, cotton mask, polyester gaiter, surgical mask, HME (Covidien), and simultaneous HME with surgical mask, were compared with an unmasked control. A nebulizer (Misty Max; AirLife) set at 6 L/min was connected to the manikin lungs to simulate particle exposure. Experiments were performed with 3 replicates for 30 seconds each, and a windowed moving mean for each 5-second particle concentration measurement was computed to account for small periodic fluctuations.

Electrocautery Simulation

Simulation was performed in an ex vivo pig trachea specimen. The OPC intake port was placed at approximate head level (1.5 m), with various horizontal distances from the tracheostomy site to represent the positioning of operating room team members. Respirable particle generation during 30 seconds of continuous electrocautery of the paratracheal muscles was computed.

Statistical Analysis

Mean background particle concentration was measured in a quiet room for each session and subtracted from the experimental condition as previously described.13,22 We used MATLAB R2017b, version 9.3.0 (MathWorks), to perform 1-way analysis of variance with pairwise comparison to assess particle concentration differences during mask conditions. Two-sample t test was used to compare differences in aerosolized particles during the various experimental setups, and Cohen d was calculated to determine the effect size. Prism statistical software, version 8 (GraphPad Software), was used for data visualization. A 2-sided value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Aerosolization During Tracheostomy Care: Cough, Suction, Nebulization

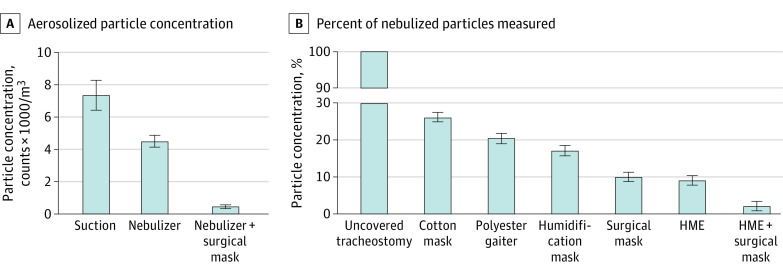

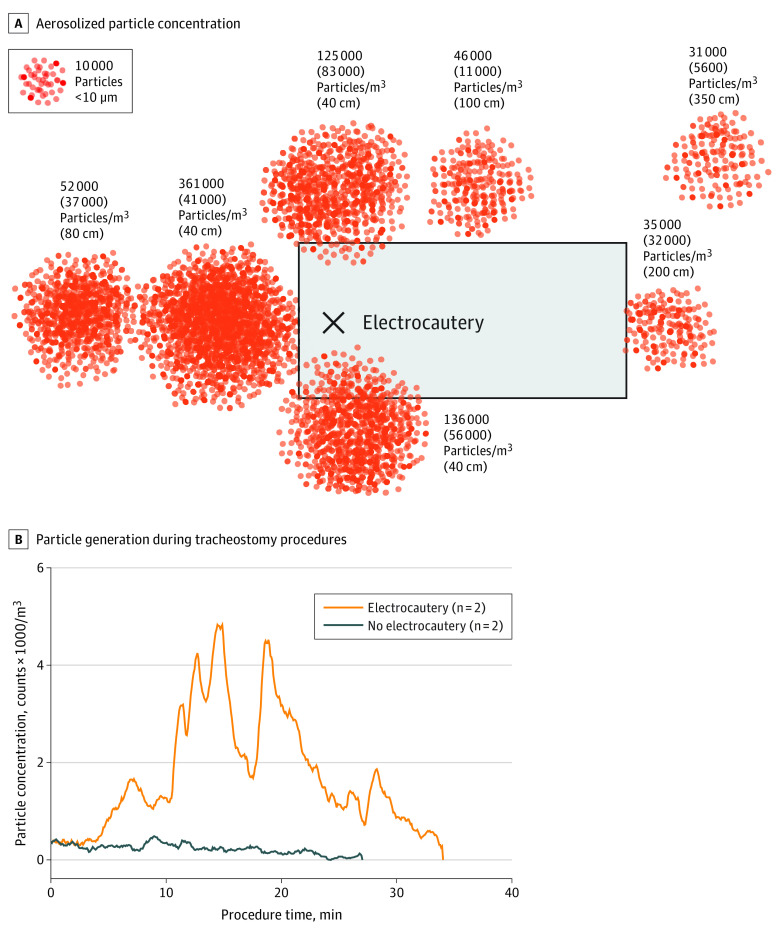

Cough events increased aerosol particle concentrations in all measured locations (Figure 2A). Cough generated the greatest concentration of particles, followed by open suction, and then airway nebulization (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Surgical mask use during airway nebulization decreased respirable particle counts by 91% (410 vs 4430 particles/m3 per 5 seconds) compared with nebulization without a covering (mean difference, 4020 particles/m3 [95% CI, 3205-4830 particles/m3]; Cohen d = 17.2) (Figure 3A).

Figure 2. Room Distribution of Aerosolized Particles Following Cough Through Tracheostomy.

A, Values indicate the mean (SD) aerosolized particle concentration quantified at 4 horizontal distances from the tracheostomy site during 30 seconds of simulated cough: 40 cm, represents bedside nurse; 100 cm, assistant; 200 cm, patient foot; and 350 cm, observer. B, Fluorescein dye spread after cough simulation from the tracheostoma during the tracheostomy procedure in a pig.

Figure 3. Reduction of Aerosol Spread During Tracheostomy Open Suction and Nebulization by Masks and Heat Moisture Exchangers (HMEs).

A, Aerosolized particle concentration during 30 seconds of open suction or airway humidification with or without a surgical mask covering the tracheostomy. Surgical mask use substantially reduces measured particles by 4020 particles/m3 (95% CI, 3205-4830 particles/m3; Cohen d = 17.2) during airway humidification. B, Percent of particles measured with use of various masks relative to particles measured with the uncovered tracheostomy. All coverings decrease particle concentration compared with the uncovered tracheostomy. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Mask Effectiveness

All masks substantially decreased particle counts when each was individually compared with no tracheostomy covering (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Compared with particles measured with an uncovered tracheostomy, particle concentration was decreased with a tracheostomy covered with a cotton mask by 73.8% (95% CI, 63.0%-84.5%; d = 3.8), with a polyester gaiter by 79.5% (95% CI, 68.7%-90.3%; d = 7.2), and with a humidification mask by 82.8% (95% CI, 72.0%-93.7%; d = 8.6). When used separately, the surgical mask and HME showed similar effectiveness, reducing particle concentration by 89.9% (95% CI, 79.3%-100.6%; d = 12.8) for the surgical mask and 91.0% (95% CI, 80.2%-101.7%; d = 19.0) for the HME. When used together, the surgical mask and HME were associated with reducing particle concentration by 97.9% (95% CI, 87.2%-108.7%; d = 29.4). Simultaneous use of a surgical mask and HME was associated with decreased particle concentration compared with either the HME (95% CI, 1.6%-12.3%; d = 1.2) or surgical mask (95% CI, 2.7%-13.2%; d = 1.9) used independently (Figure 3B).

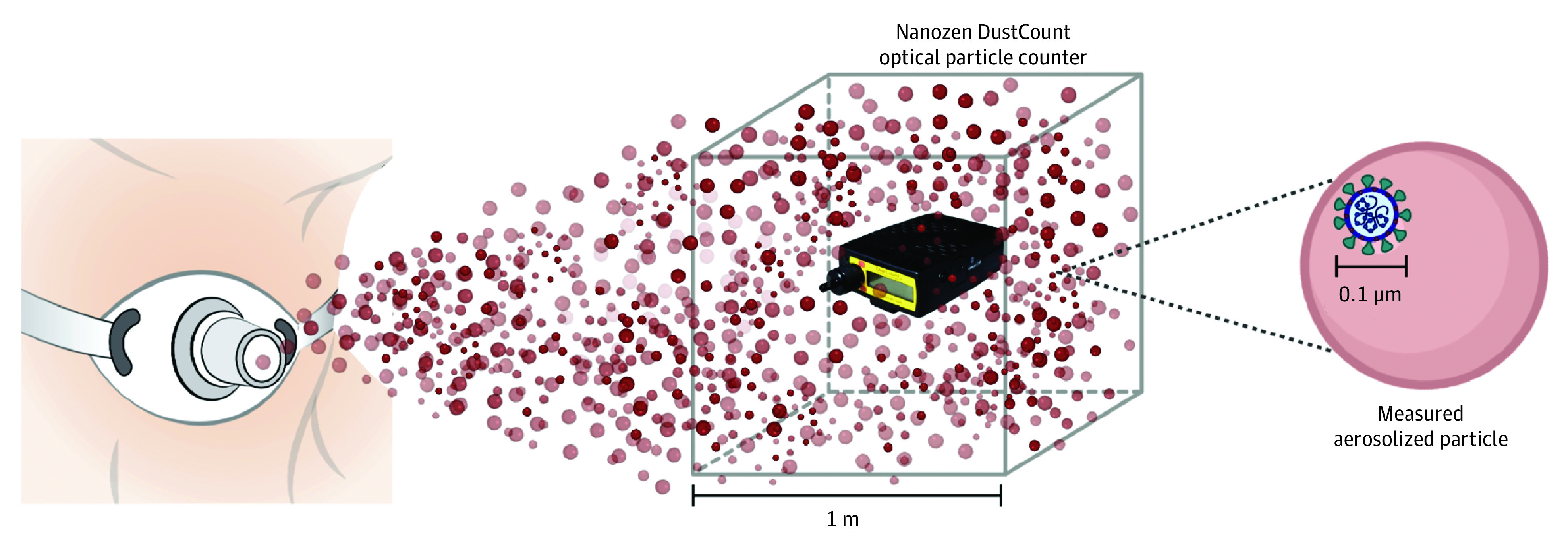

Aerosolization During Surgery: Electrocautery Simulation and Swine Tracheostomy Procedure

During simulation in all measured locations, electrocautery of ex vivo tracheal tissue generated increased aerosolized particles compared with baseline (Table). The highest concentrations were measured in locations of anesthesia (at 40 cm) and surgeon right and left (at 40 cm) (Figure 4A). Electrocautery generated more particle counts than cough, suction, and nebulizer events. During the swine tracheostomy procedure, between the time from skin incision to tracheal incision, aerosolized particle concentration was increased by 1500 particles/m3 per 5-second interval (95% CI, 1380-1610 particles/m3 per 5-second interval; d = 1.8) in cases using electrocautery compared with cases using cold instrumentation (Figure 4B).

Table. Room Distribution of Aerosolized Particles After Cough Through Tracheostomy and During Electrocautery.

| Measurement location | Horizontal distance from tracheostoma, cm | Particle concentration, mean (SD), counts/m3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrocautery | Cough | ||

| Surgeon left or patient left | 40 | 125 000 (83 000)a | 68 000 (16 000)a |

| Surgeon right | 40 | 136 000 (56 000)a | ND |

| Scrub nurse, trainee, or assistant | 100 | 46 000 (11 000)a | 71 000 (20 000)a |

| Patient foot | 200 | 35 000 (32 000)a | 44 000 (34 000)a |

| Circulating nurse or distanced observer | 350 | 31 000 (5600)a | 32 000 (2900)a |

| Close anesthesia | 40 | 361 000 (41 000)a | ND |

| Far anesthesia | 80 | 52 000 (37 000)a | ND |

| Background particle measurement | NA | 19 000 (800) | 8900 (8200) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

Denotes experimental particle concentration values calculated by subtracting the background particle concentration.

Figure 4. Particle Generation During Electrocautery.

A, Aerosolized particle concentration shown as mean (SD) particles per cubic meter during 30 seconds of continuous bipolar electrocautery of tracheal tissue at various horizontal distances from the tracheostomy site: surgeon left at 40 cm, surgeon right at 40 cm, scrub nurse or trainee at 100 cm, patient foot at 200 cm, circulating nurse at 350 cm, anesthesia at 40 cm, and anesthesia at 80 cm. B, Particle generation during tracheostomy procedures in swine shows increased aerosolization during electrocautery use (from skin incision to tracheal incision) compared with cold instrumentation.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first study to quantify aerosolization during tracheostomy surgery and simulated tracheostomy care. Although masks have been at the forefront of primary public health efforts to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission, there is limited evidence-based guidance for mask use in patients with a tracheostomy. This study evaluated several commercially available tracheostomy coverings and showed that, among them, the combination of a standard HME and surgical mask was most effective, decreasing aerosol particle measurement by 97.9% for uncovered tracheostomies. These data may inform development of new protocols to protect health care workers from nosocomial viral transmission during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care.

Although tracheostomy surgery is a designated AGP, tracheostomy care in the form of routine nursing interventions for patients with a tracheostomy (ie, suctioning, manipulation, and nebulization) are only considered possible AGPs.9 This designation is owing to insufficient data correlating these clinical activities with nosocomial transmission. Previously, Simonds et al29 showed dispersal of small and medium-sized aerosolized particles (<5 μm) from a nebulizer in patients without a tracheostomy to inform the management of influenza viruses. The present study shows that both open suctioning and nebulization of the tracheostomy increase respirable aerosolized particles, as measured by an OPC, and should be designated an AGP. Furthermore, tracheostomy suctioning and nebulization may lead to tracheal irritation and cough events, which generate additional aerosols. If tolerated by patients, placement of a surgical mask over the tracheostomy during nebulization is recommended.30

Several recommendations have been made to reduce risk to health care workers during the care of patients with tracheostomies. This study is the first, to our knowledge, to show aerosolized particle reduction by several commercially available tracheostomy coverings used in hospital and ambulatory settings. We found that the combination of standard HME and surgical mask use is most effective in reducing aerosol spread. A standard HME allows for heat and moisture exchanging in the respiratory tract while also filtering out droplets and smaller particles during patient ventilation. In addition, some HMEs have specifically been developed with filters having a non–SARS-CoV-2 viral filtration effectiveness of 99%.31 Patients with a tracheostomy should wear an HME in combination with a surgical mask to reduce nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory virus transmission to health care workers during hospital transport and other health care interactions.

In the operating room, tracheostomy procedures for patients who are under investigation or who have tested positive for COVID-19 are ideally performed in negative-pressure rooms equipped with high-efficiency particulate air filters to reduce risk of viral transmission.32,33,34 During surgery, the use of electrocautery generates aerosolized particles from the dissected tissue, which may contain virus, as in the case of HIV-1.35,36 The present study revealed that electrocautery of tracheal tissue increased aerosolized particle measurement compared with baseline, both during simulation and in vivo surgical procedures performed in swine. Although the particle count detected during electrocautery was greater than that in aerosols generated by cough, it should be recognized that the former may not be infectious in the case of SARS-CoV-2. The dissected skin, subcutaneous layers, fat, and platysma have not been shown to have a high load of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Furthermore, studies of patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 have not isolated viral RNA from the serum, in contrast to sputum from the lungs and airways.37 However, the main SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, is located in numerous tissues throughout the human body, and SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in multiple organs, including the ear,38 heart, liver, brain, and kidneys,39 making it possible for neck soft tissue to be infectious. In both head and neck surgery and gynecology, avoidance of electrocautery has been proposed for patients who test positive for human papillomavirus to avoid occupational exposure to viral DNA.40,41 Similarly, avoidance of electrocautery represents a technique to limit aerosol exposure during tracheostomy or any surgery involving potentially infectious tissue (ie, SARS-CoV-2).

Limitations

Although this study quantified aerosolization during tracheostomy surgery and tracheostomy care, there are several limitations. The OPC used in this study has a minimum particle diameter detection of 0.3 μm, which is larger than the SARS-CoV-2 diameter of 0.1 μm. Therefore, it is likely that the reported data represent an underestimate of aerosolized particles containing SARS-CoV-2. Although this study did not quantify aerosolization during tracheostomy surgery or tracheostomy care in clinical settings, aerosol spread was measured during in vivo swine tracheostomy surgery because the swine airway is similar to the human airway.

Conclusions

Tracheostomy care, including suctioning, nebulization, and cough, generate aerosolized particles, which may be filtered by mask placement over the tracheostomy. The present study quantified the concentration of respirable particles generated by various tracheostomy care procedures and showed that the combination of an HME and surgical mask over the tracheostomy reduced aerosol concentration to the greatest degree. Quantifying these risks in the context of SARS-CoV-2 will inform appropriate personal protective equipment choices and the development of new protocols to minimize viral entry into the aerodigestive tract of surgeons and health care workers. Although this study was prompted by the novel SARS-CoV-2, these results are applicable to emerging and future aerosol transmissible diseases to prevent nosocomial viral spread during tracheostomy care. Further studies to explore particle aerosolization during surgery and care of patients with a tracheostomy will enable better understanding of the clinical risk of viral transmission during tracheostomy, cough, suctioning, and nebulization.

eTable 1. Aerosolized Particle Spread During Suction and Nebulization

eTable 2. Particle Reduction With Tracheostomy Coverings Compared to Uncovered Tracheostomy

References

- 1.Liu Y, Ning Z, Chen Y, et al. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582(7813):557-560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cevik M, Kuppalli K, Kindrachuk J, Peiris M. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ. 2020;371:m3862. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bake B, Larsson P, Ljungkvist G, Ljungström E, Olin AC. Exhaled particles and small airways. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-0970-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cascella, M., Rajnik, M., Cuomo, A., Dulebohn, S. C. & Di Napoli, R.. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thamboo A, Lea J, Sommer DD, et al. Clinical evidence based review and recommendations of aerosol generating medical procedures in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00425-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843-1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrath BA, Ashby N, Birchall M, et al. Multidisciplinary guidance for safe tracheostomy care during the COVID-19 pandemic: the NHS National Patient Safety Improvement Programme (NatPatSIP). Anaesthesia. 2020;75(12):1659-1670. doi: 10.1111/anae.15120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miles BA, Schiff B, Ganly I, et al. Tracheostomy during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Recommendations from the New York Head and Neck Society. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1282-1290. doi: 10.1002/hed.26166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen WQ, Ling WH, Lu CY, et al. Which preventive measures might protect health care workers from SARS? BMC Public Health. 2009;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H-J, Su YY, Xu SL, et al. Asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in close contacts of COVID-19 patients: a seroepidemiological study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa771. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meister KD, Pandian V, Hillel AT, et al. Multidisciplinary Safety Recommendations After Tracheostomy During COVID-19 Pandemic: State of the Art Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):984-1000. doi: 10.1177/0194599820961990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson JP, Wong DN, Verco L, Carter R, Dzidowski M, Chan PY. Measurement of airborne particle exposure during simulated tracheal intubation using various proposed aerosol containment devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(12):1587-1595. doi: 10.1111/anae.15188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertroche JT, Pipkorn P, Zolkind P, Buchman CA, Zevallos JP. Negative-pressure aerosol cover for COVID-19 tracheostomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(7):672-674. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filho WA, Teles TSPG, da Fonseca MRS, et al. Barrier device prototype for open tracheotomy during COVID-19 pandemic. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020;47(4):692-696. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canelli R, Connor CW, Gonzalez M, Nozari A, Ortega R. Barrier enclosure during endotracheal intubation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1957-1958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betancourt-Ramirez A, Yelon JA, Boland P, Amaturo M. A technique to minimize aerosolization during percutaneous tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Am Surg. 2020;86(8):904-906. doi: 10.1177/0003134820943102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster P, Cheung T, Craft P, et al. Novel approach to reduce transmission of COVID-19 during tracheostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(6):1102-1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown J, Gregson FKA, Shrimpton A, et al. A quantitative evaluation of aerosol generation during tracheal intubation and extubation. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(2):174-181. doi: 10.1111/anae.15292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doggett N, Chow C-W, Mubareka S. Characterization of experimental and clinical bioaerosol generation during potential aerosol-generating procedures. Chest. 2020;158(6):2467-2473. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Neil CA, Li J, Leavey A, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program . Characterization of aerosols generated during patient care activities. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(8):1335-1341. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Workman AD, Jafari A, Welling DB, et al. Airborne aerosol generation during endonasal procedures in the era of COVID-19: risks and recommendations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(3):465-470. doi: 10.1177/0194599820931805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rameau A, Lee M, Enver N, Sulica L. Is office laryngoscopy an aerosol-generating procedure? Laryngoscope. 2020;130(11):2637-2642. doi: 10.1002/lary.28973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao R, Workman AD, Puka E, Juang J, Naunheim MR, Song PC. Aerosolization during common ventilation scenarios. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(4):702-704. doi: 10.1177/0194599820933595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Committee for Standardization (CEN) . Workplace Atmospheres. Size Fraction Definitions for Measurement of Airborne Particles. British Standards Institute Staff; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ACGIH. TLV/BEI guidelines. 2021. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.acgih.org/science/tlv-bei-guidelines/

- 27.American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. Particle Size-Selective Sampling in the Workplace: Report of the ACGIH Technical Committee on Air Sampling Procedures. American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beuret P, Roux C, Auclair A, Nourdine K, Kaaki M, Carton MJ. Interest of an objective evaluation of cough during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(6):1090-1093. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1404-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simonds AK, Hanak A, Chatwin M, et al. Evaluation of droplet dispersion during non-invasive ventilation, oxygen therapy, nebuliser treatment and chest physiotherapy in clinical practice: implications for management of pandemic influenza and other airborne infections. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(46):131-172. doi: 10.3310/hta14460-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kligerman MP, Vukkadala N, Tsang RKY, et al. Managing head and neck cancer patients with tracheostomy or laryngectomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1209-1213. doi: 10.1002/hed.26171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atos. Provox Micron HME. Accessed February 6, 2021. https://www.atosmedical.com/product/provox-micron-hme/

- 32.Soma M, Jacobson I, Brewer J, Blondin A, Davidson G, Singham S. Operative team checklist for aerosol generating procedures to minimise exposure of healthcare workers to SARS-CoV-2. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;134:110075. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyd CP, Desiato VM, Nguyen SA, et al. Tracheostomy protocols during COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1297-1302. doi: 10.1002/hed.26192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mecham JC, Thomas OJ, Pirgousis P, Janus JR. Utility of tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 and other special considerations. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(11):2546-2549. doi: 10.1002/lary.28734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fletcher JN, Mew D, DesCôteaux JG. Dissemination of melanoma cells within electrocautery plume. Am J Surg. 1999;178(1):57-59. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)00109-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson GK, Robinson WS. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) in the vapors of surgical power instruments. J Med Virol. 1991;33(1):47-50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890330110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465-469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frazier KM, Hooper JE, Mostafa HH, Stewart CM. SARS-CoV-2 virus isolated from the mastoid and middle ear: implications for COVID-19 precautions during ear surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(10):964-966. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):590-592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Q, Hu X, Zhou J, Zhao M, Zhu X, Zhu X. Human papillomavirus DNA in surgical smoke during cervical loop electrosurgical excision procedures and its impact on the surgeon. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3643-3654. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S201975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subbarayan RS, Shew M, Enders J, Bur AM, Thomas SM. Occupational exposure of oropharyngeal human papillomavirus amongst otolaryngologists. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2366-2371. doi: 10.1002/lary.28383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Aerosolized Particle Spread During Suction and Nebulization

eTable 2. Particle Reduction With Tracheostomy Coverings Compared to Uncovered Tracheostomy