Abstract

The communication phenomenon known as conversational entrainment occurs when dialogue partners align or adapt their behavior to one another while conversing. Associated with rapport, trust, and communicative efficiency, entrainment appears to facilitate conversational success. In this work, we explore how conversational partners entrain or align on articulatory precision or the clarity with which speakers articulate their spoken productions. Articulatory precision also has implications for conversational success as precise articulation can enhance speech understanding and intelligibility. However, in conversational speech, speakers tend to reduce their articulatory precision, preferring low-cost, imprecise speech. Speakers may adapt their articulation and become more precise depending on feedback from their listeners. Given the potential of entrainment, we are interested in how conversational partners adapt or entrain their articulatory precision to one another. We explore this phenomenon in 57 task-based dialogues. Controlling for the influence of speaking rate, we find that speakers entrain on articulatory precision, with significant alignment on articulation of consonants. We discuss the potential applications that speaker alignment on precision might have for modeling conversation and implementing strategies for enhancing communicative success in human-human and human-computer interactions.

Keywords: entrainment, alignment, articulatory precision, human-computer interaction, dialog systems

1. Introduction

Conversational partners have been found to modify or adapt their behaviors to become more like one another. Known as conversational entrainment or alignment, the phenomenon is considered a potentially powerful communicative device that facilitates success by enhancing both social connection and mutual understanding [1]–[3]. Entrainment has been observed in body language, lexical content, acoustic-prosodic features such as pitch and intensity, and acoustic articulatory features (e.g. spectral features) [4]–[6]. Alignment on these features has been found to be related to higher rapport, trust, efficiency, and agreement [7]–[10]. However, there is a critical aspect of spoken dialogue on which entrainment has not been studied, and which has important implications for human-human and human-computer interactions. Articulatory precision, or how clearly speakers articulate their spoken productions, plays a key role in speech understanding and intelligibility [11], [12]. While the role of precise articulation has been studied in clinical contexts, none of the previous work explores how an interlocutors’ articulation affects his or her partner. In this work, we are interested in whether conversational partners entrain on articulatory precision.

How conversational partners might modify the articulation of their spoken productions in response to one another is an open question. When considering interlocutors individually, it has been observed that they tend to reduce their articulation in conversation. According to Lindblom’s hypo-hyper articulate theory (H&H), speakers default to reduced articulatory precision, preferring low-cost speech or speech that requires the least amount of effort [13]. However, the H&H theory also postulates that speakers will engage in more effortful, precise articulation when they receive evidence that their listener requires additional acoustic information (e.g. when a listener asks for a clarification). Thus, the degree to which speakers reduce/increase their articulatory precision occurs on a continuum, largely dependent on listener feedback.

The H&H theory explains why an individual speaker might modify their articulation; however, the theoretical framework provides less insight into how articulation might change when individuals are engaged in a joint dialogue where there is also potential for entrainment to occur. Conversation is a dynamic and joint activity, with partners taking on the role of both speaker and listener. In a conversation, dialogue partners exchange, adapt, and influence one another on multiple levels, and the dynamic described by the H&H theory becomes more complex when a speaker’s preference for low-cost, imprecise speech might influence their partner’s preference for low-cost, imprecise speech through the phenomenon of entrainment.

Here, we investigate whether there is evidence of entrainment on articulatory precision with a corpus of 57 task-based conversations involving typical/healthy (i.e. no speech disorders, hearing impairment, etc.) adults. Articulatory precision is measured as an average score across all phonemes and also split at the level of vowels and consonants. We do this using an automated measure of pronunciation which takes perfectly read speech as the model for pronunciation [14]. Entrainment of articulatory precision is measured as a form of local dyadic alignment where we analyze how conversational partners modify their articulation on a turn-by-turn basis. The results of our study show that conversational partners entrain on this measure of articulatory precision in conversation, even when controlling for speaking rate.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section provides more details regarding the dataset used for this analysis. Section 3 provides details on the automated measure of articulatory precision and our approach for assessing entrainment on articulatory precision. In Section 4, we describe our results. We discuss these results in Section 5.

2. Dataset

We utilize the corpus described in detail by Borrie and colleagues [6], consisting of 57 experimentally elicited conversations involving 114 college-aged participants (mean age = 22.41 years), all participants were native speakers of American English with no self-reported history of speech, language, hearing, or cognitive impairment. Of the dyads, 43 were female-female, 13 were female-male, and one was male-male. Additional corpus statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1:

Corpus statistics.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Dialogue length (min) | 10.5 | .33 |

| Adjacent IPUs | 184.2 | 39.3 |

| Articulatory precision | −1.84 | 1.6 |

| Articulatory precision - Vowels | −2.10 | .40 |

| Articulatory precision - Consonants | −1.62 | .43 |

| Speaking rate | 3.58 | .38 |

The conversations were goal-oriented and elicited using the Diapix task. The Diapix task is a collaborative “spot-the difference” activity where conversational participants are each given an image of a similar scene. Each participant is told not to show their image to their partner, and they are encouraged to compare their “scenes” verbally to identify a set number of differences between the two pictures [15]. The dyads were given 10 minutes to work on the task and were encouraged to find as many of the differences as possible. Additional details of the dialogue task, instructions and recording equipment are specified in [6]. All audio files were normalized using a standard loudness normalization procedure based on a reference level and down-sampled to 16 kHz.

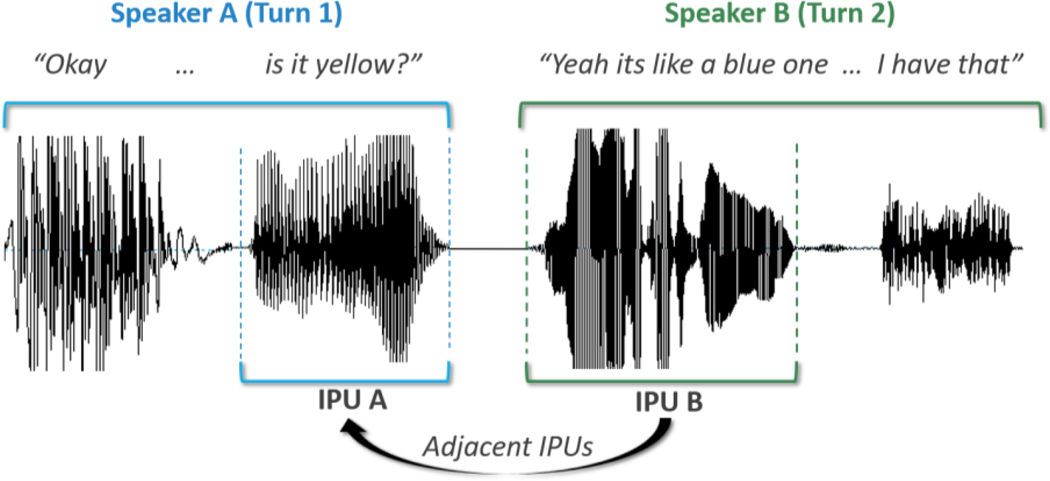

With this corpus, trained research assistants had manually coded for all speaker utterances, identifying the beginning and end of each utterance. Using this coding, we identified all adjacent IPUs or inter-pausal units in the corpus. An IPU is a pause-free unit of speech from a single speaker separated from any other speech by at least 50ms [16]. Illustrated in Figure 1, adjacent IPUs are consecutive inter-pausal units uttered by two different speakers. With this definition, overlap is allowed.

Figure 1:

Example of adjacent IPUs in conversational dialogue where the ellipses represents a pause of 50ms or greater

We obtained the orthographic transcriptions for all adjacent IPUs. Across the corpus as a whole, adjacent IPUs make up 70% of the dialogue. Some dyads have a greater dialogue exchange rate, resulting in more adjacent IPUs than other dyads. The mean and standard deviation for adjacent IPUs is given in Table 1. To obtain the transcriptions, we utilized a third-party service, GoTranscript (www.gotranscript.com). Third party services have become a common approach for transcription services and evaluations have shown these services can provide reliable results [17]. In the following analyses, we ignored filled pauses, exclamations, and laughter.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measuring Articulatory Precision

To measure articulatory precision, we utilized an approach to automatically score pronunciation based on work by [14], [18], which assesses pronunciation as the log-posterior probability of aligned phonemes normalized by phoneme duration. With this methodology, we can obtain an articulatory precision score for every phoneme in the corpus.

We first force-aligned the orthographic transcriptions for each IPU at the phoneme-level using an acoustic model for English based on the LibriSpeech corpus [19]. The alignment provided the start and end frame indices for each phoneme. A single coder (one of the authors) manually evaluated the results of the automated alignment for 20% of the dialogue using Praat [20] to ensure that the start and end indices being identified were accurately capturing the correct phonemes according to the transcripts and audio. With the alignment and the audio, the articulatory precision score for a phoneme p was then defined as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Op is the corresponding acoustic segment, |Op| is the number of frames in the segment, and Q is the set of all phonemes. The above equation assumes equal priors for all phonemes. If the phoneme returned by the acoustic model is the same as the target phoneme p, then the articulatory precision score is equal to 0. Otherwise, the score will be negative; the smaller the score (i.e. the farther from zero), the farther the pronunciation is from that defined by the acoustic model built from the LibriSpeech corpus. Because the LibriSpeech corpus consists of “read” speech, this measure is an evaluation of articulatory precision as defined by “read” speech.

With the individual phoneme scores, we calculated a single articulatory precision score per speaker by averaging the phoneme precision scores across each adjacent IPU. We also calculated separately an average score for vowels and consonants. Pronunciation of vowels and consonants can differ significantly, and these differences have been found to be important in assessing other aspects of speech [21]. Differences in alignment on vowels and consonants may provide different insights into how precision is related to conversational success.

4.1. Measuring Entrainment

Entrainment has been assessed along two primary time-scales referred to as local and global [16], [22]. Local entrainment is measured on a turn-by-turn basis while global entrainment assesses change across an entire conversation. Here, we are interested in how a speaker’s use of low-cost imprecise articulation influences their partner’s articulatory precision at the local level of entrainment.

We follow an approach established in prior work to explore turn-by-turn alignment using a mixed model analysis [23]. Eon-Suk and colleagues and Seidl and colleagues have used this approach to explore alignment on pitch in interactions between mothers and their infants [24], [25]. We utilize a similar approach here to explore how one speaker’s articulatory precision influences their partner’s using the articulatory precision scores from adjacent IPUs. We split the data into two mixed model analyses, with one model for the directional influence of each speaker on their partner. We identify each speaker in each dyad as either speaker A or speaker B. Speaker A is defined as the participant who spoke first at the very beginning of the interaction. In model A, we analyze all adjacent IPUs where speaker A spoke the first IPU in a pair of adjacent IPUs and we explore how speaker A’s articulatory precision influences speaker B’s. In model B, we look at all adjacent IPUs where the other participant, speaker B, spoke the first IPU in a pair of adjacent IPUs and we explore how speaker B’s articulatory precision influences speaker A.

Both models are fit to predict a speaker’s articulatory precision based on the articulatory precision of their partner’s previous utterance. The random structure includes a random intercept for each dyad. We utilize a random intercept to capture intra-dyad variability on alignment because there is evidence to suggest that different dyads align differently [9], [26]. We control for speaking rate (words per second) as a relationship between speaking rate and articulatory precision has been observed with slower rates tracking with greater precision [27]. The degree to which a speaker’s articulatory precision explains their partner’s captures alignment as the influence of one speaker on the other.

4. Results

We entered the articulatory precision scores for adjacent IPUs into a mixed model using the R package lme4 as,

FirstAP is the articulatory precision of the primary speaker, SecondAP is the articulatory precision of the dependent speaker’s immediately following utterance. Speaking rate is the speaking rate for SecondAP and (1|Dyad) captures intra-dyad variability on alignment. We explored a potential interaction between speaking rate and FirstAP; however, we did not observe a significant effect. We therefore report the results without the interaction. The full results are given in Table 2. We assessed alignment on articulatory precision as well as for vowels and consonants separately. P-values were calculated via Satterthwaite’s degrees of freedom method [28].

Table 2:

Alignment on articulatory precision. Constant is not reported.

| Overall | Estimate | SE | df |

|---|---|---|---|

| Articulatory Precision, predicting Speaker B | |||

| Speaker A AP (FirstAP) | .06* | .01 | 5750 |

| Speaking Rate | −.11** | .01 | 5745 |

| Articulatory Precision, predicting Speaker A | |||

| Speaker B AP (FirstAP) | .02+ | .01 | 5830 |

| Speaking Rate | −.14** | .01 | 5811 |

| Vowels | |||

| Articulatory Precision of Vowels, predicting Speaker B | |||

| Speaker A AP (FirstAP) | .01 | .02 | 2569 |

| Speaking Rate | −.21** | .02 | 2566 |

| Articulatory Precision Vowels, predicting Speaker A | |||

| Speaker B AP (FirstAP) | −.03 | .02 | 2521 |

| Speaking Rate | −.09** | .03 | 2487 |

| Consonants | |||

| Articulatory Precision of Consonants, predicting Speaker B | |||

| Speaker A AP (FirstAP) | .06* | .02 | 2553 |

| Speaking Rate | −.29** | .02 | 2549 |

| Articulatory Precision of Consonants, predicting Speaker A | |||

| Speaker B AP (FirstAP) | .04+ | .02 | 2553 |

| Speaking Rate | −.16** | .03 | 2549 |

P-values via Satterthwaite’s degrees of freedom;

p < .001 indicated with,

p < .01 indicated with,

p < .1 indicated with

We find alignment overall for the first speaker (p = .005) but not for the second speaker (p = .09) controlling for speaking rate. That is, regardless of speaking rate, the second speaker’s articulatory precision is predicted by the first speakers’ precision. The beta for articulatory precision, βA = .06 indicates a small, positive alignment between speakers on their pronunciation. This means that the articulatory precision of the second speaker increased with a corresponding increase in the first speaker’s articulatory precision. This suggests speakers moved in the same direction – as the first speaker became more precise in articulation, so did the second speaker.

Looking at alignment on vowels and consonants separately, we do not observe a significant influence of either speaker on the other regarding the articulation of vowels. However, we do observe an influence on consonant production. For both speaker models, we find a significant relationship between speakers’ articulation of consonants (p = .008 and p = .05). Similar to what was found overall, it appears that the individual who speaks first in the conversation has a slightly greater influence on their partner’s articulation of consonants (βA = .06) than the individual who speaks second (βA = .04).

We further evaluated whether these results were meaningful, and not capturing accidental or coincidental phenomena using an approach established in prior work of evaluating pseudo interactions [29]–[32]. We generated a ‘sham’ dataset of artificial conversations by randomly mixing the articulatory precision scores of conversational partners. Running the same analysis, we do not find a significant effect of ‘false’ speaking partners on one another (p > .1 for all combinations). This supports that speakers are genuinely influencing the articulatory precision of their partner.

5. Discussion

We investigated whether conversational partners influenced one another in their articulatory precision in a corpus of experimentally elicited conversations. Our analyses revealed that speakers align their articulation with the articulatory precision of one speaker significantly predicting that of their partner. This entrainment of articulatory precision appears to be driven by precision of consonant production with significant alignment on precision of consonants but not vowels.

Observing significant entrainment on articulation of consonants but not vowels indicates that consonants may be more amenable to articulatory adaptation. One possible explanation for this is that consonant production affords more articulatory information than vowels and are thus easier to align on [33], [34]. For example, consonants are produced with a constriction of airflow, which provides more information about the place of articulation. Another possible explanation is based on prior perceptual research which suggests that vowels have more relative importance in the recognition of fluent speech than consonants [34]. It is possible that in entrained conversations consonants are less crucial for communicating the speaker’s intended message and provide a better target for reduction. Although, we acknowledge that coarticulation drastically blurs the boundaries between consonants and vowels, and that such divisions, particularly in the context of conversational speech, may be somewhat arbitrary [35].

The initiating speaker in the conversations appeared to have a greater influence on their partner. We do observe some influence of the second speaker on the first speaker, with the first speaker approaching significant alignment to their partner. One could postulate that the individuals who initiated the interactions have more assertive personalities, and/or by speaking first, they established a dominant role in the conversation, which may have influenced greater alignment on the part of the second speaker. Indeed, prior work has reported an effect of speaker role on alignment with individuals in subordinate roles accommodating more to their partner [36].

Our findings of conversational entrainment of articulatory precision have potential implications for both human-human and human-computer interactions. In human-human interactions, the H&H model has traditionally described a speaker preference for imprecise articulation and yet, a listener preference for precise articulation. Alignment on articulation adds a dynamic to this relationship where conversational partners act together, moving together towards an articulatory balance. Future work will explore how conversational partners define and achieve articulatory balance. While we find that speakers are aligning, conversational partners may be aligning to be more similar on precise articulation or they may be aligning on imprecise articulation. If speakers are aligning on imprecise articulation, this may enable speakers to communicate with less articulatory overhead. Entrained conversational partners have been found to be able to communicate with less semantic information, fewer words, and have fewer difficulties with lexical search [37]–[39]. Future work will explore the relationship between degree of entrainment and articulatory precision.

With regard to human-computer interaction, speakers have been found to hyper articulate when conversing with computers [40]. Often speakers hyperarticulate when correcting recognition errors [41] but hyper articulation has been observed generally as well. Unfortunately, hypo and hyper articulation presents a difficult source of variability. Recent work has focused on how to detect hypo hyper articulation [42]. Our work suggests that speakers may change their hypo and hyper articulation given the articulation of their partner. Understanding how and why speakers significantly vary their articulation can enable more realistic dialog systems; alignment may enable systems to find a more optimal, natural balance between hypo-and hyperarticulate speech with human partners and reduce variability in hypo hyper articulation.

6. Conclusions

Articulatory precision plays an important role in communication, as does the phenomenon of conversational entrainment. Here, we found that conversational partners entrain on the precision of their spoken productions and this result held true after controlling for speaking rate, indicating that this finding is not indicative of some other phenomenon but is alignment on articulatory precision. While previous studies have found entrainment on articulatory features based largely on spectral information, to our knowledge, this is the first exploration of entrainment of articulatory precision. Future work will expand on these findings to explore whether conversational partners who exhibit high levels of entrainment also communicate with less articulatory overhead and how this phenomenon might contribute to conversational success.

7. Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health Grants R21DC016084-01 and R01DC006859.

8. References

- [1].Pickering MJ and Garrod S, “An integrated theory of language production and comprehension.,” Behav. Brain Sci, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 329–47, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Giles H, Coupland N, and Coupland J, “Accomodation theory: Communication, context, and consequence,” Contexts of accomodation: Developments in applied sociolinguistics. pp. 1–68, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Borrie SA and Liss JM, “Rhythm as a coordinating device: entrainment with disordered speech.,” J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 815–24, Jun. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beňuš Š, “Conversational entrainment in the use of discourse markers,” Smart Innov. Syst. Technol, vol. 26, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Scaglione A, Lacross A, Kawabata K, and Berisha V, “A Convex Model for Linguistic Influence in Group Conversations,” in INTERSPEECH, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Borrie S, Barrett T, Willi M, and Berisha V, “Syncing up for a good conversation: A clinically-meaningful methodolgoy for capturing conversational entrainment in the speech domain,” J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lubold N. and Pon-Barry H, “Acoustic-Prosodic Entrainment and Rapport in Collaborative Learning Dialogues Categories and Subject Descriptors,” Proc. ACM Work. Multimodal Learn. Anal. Work. Gd. Chall., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Friedberg H, Litman D, and Paletz SBF, “Lexical Entrainment and Success in Student Engineering Groups,” in Spoken Language Technology Workshop, 2012, pp. 404–409. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vaughan B, “Prosodic synchrony in co-operative task-based dialogues: A measure of agreement and disagreement,” INTERSPEECH, pp. 1865–1868, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Borrie S, Lubold N, and Pon-Barry H, “Disordered speech disrupts conversational entrainment: a study of acoustic-prosodic entrainment and communicative success in populations with communication challenges.,” Front. Psychol, vol. 6, no. August, p. 1187, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lam J. and Tjaden K, “Intelligibility of Clear Speech: Effect of Instruction,” J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 1429–1440, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Park S, Theodoros D, Finch E, and Cardell E, “Be Clear: A New Intensive Speech Treatment for Adults with Nonprogressive Dysarthria,” Am. J. Speech-Language Pathol, vol. 25, no. February, pp. 97–110, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lindblom B, “Explaining Phonetic Variation: A Sketch of the H&H Theory,” in Speech Production and Speech Modelling, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tu M, Grabek A, Liss J, and Berisha V, “Investigating the role of L1 in automatic pronunciation evaluation of L2 speech,” INTERSPEECH, pp. 1636–1640, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Van Engen KJ, Baese-Berk M, Baker RE, Choi A, Kim M, and Bradlow AR, “The Wildcat Corpus of Native-and Foreign-accented English: Communicative Efficiency across Conversational Dyads with Varying Language Alignment Profiles,” Lang. Speech, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 510–540, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Levitan R. and Hirschberg J, “Measuring acoustic-prosodic entrainment with respect to multiple levels and dimensions.,” INTERSPEECH, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhou H, Baskov D, and Lease M, “Crowdsourcing Transcription Beyond Mechanical Turk,” in First AAAI Conf on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Witt SM and Young SJ, “Phone-level pronunciation scoring and assessment for interactive language learning,” Speech Commun., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 95–108, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Panayotov V, Chen G, Povey D, and Khudanpur S, “Librispeech: An ASR corpus based on public domain audio books,” ICASSP, IEEE Int. Conf. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. - Proc., pp. 5206–5210, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Boersma P, “Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer,” Glot Int., vol. 5, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yakoub MS, Selouani SA, and O’Shaughnessy D, “Improving dysarthric speech intelligibility through resynthesized and grafted units,” Can. Conf. Electr. Comput. Eng., pp. 1523–1526, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee C-C et al. , “Computing vocal entrainment: A signal-derived PCA-based quantification scheme with application to affect analysis in married couple interactions,” Comput. Speech Lang, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 518–539, Mar. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Quene H. and Van Den Bergh H, “On multi-level modeling of data from repeated measures designs: a tutorial,” Speech Commun., vol. 43, pp. 103–121, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Eon-Suk K, Seidl A, Cristia A, Reimchen M, and Soderstrom M, “Entrainment of prosody in the interaction of mothers with their young children,” J. Child Lang, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Seidl A. et al. , “Infant-Mother Acoustic-Prosodic Alignment and Developmental Risk,” J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res, vol. 61, no. June, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lubold N. and Pon-Barry H, “Acoustic-Prosodic Entrainment and Rapport in Collaborative Learning Dialogues Categories and Subject Descriptors,” Proc. 2014 ACM Work. Multimodal Learn. Anal. Work. Gd. Chall., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nishio M. and Niimi S, “Speaking rate and its components in dysarthric speakers,” Clin. Linguist. Phonetics, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 309–317, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Satterthwaite FE, “An Approximate Distribution of Estimates of Variance,” Biometrics Bull., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 110–114, 1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Truong DKP and Heylen DD, “Measuring prosodic alignment in cooperative task-based conversations,” Interspeech, p. 1085, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [30].De Looze C, Scherer S, Vaughan B, and Campbell N, “Investigating automatic measurements of prosodic accommodation and its dynamics in social interaction,” Speech Commun., vol. 58, pp. 11–34, Mar. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bonin F. et al. , “Investigating fine temporal dynamics of prosodic and lexical accommodation,” INTERSPEECH, pp. 539–543, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Campbell N. and Scherer S, “Comparing Measures of Synchrony and Alignment in Dialogue Speech Timing with respect to Turn-taking Activity,” Interspeech 2010, no. September, pp. 2546–2549, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Johnson K, Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics, 3rd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang J, Green JR, Samal A, and Yunusova Y, “Articulatory Distinctiveness of Vowels and Consonants: A Data-Driven Approach,” J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 1539–1551, Oct. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ladefoged P, Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Langauges. Blackwell, Oxford, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pardo JS, Jay IC, Hoshino R, Hasbun SM, Sowemimo-Coker C, and Krauss RM, “Influence of Role-Switching on Phonetic Convergence in Conversation,” Discourse Process., vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 276–300, May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cassell J, Gill AJ, and Tepper PA, “Coordination in Conversation and Rapport,” in Workshop on Embodied Language Processing, 2007, pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hilliard C. and Cook SW, “Bridging Gaps in Common Ground: Speakers Design their Gestures for their Listeners,” J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Holler J. and Wilkin K, “Communicating common ground: How mutually shared knowledge influences speech and gesture in a narrative task,” Lang. Cogn. Process, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 267–289, Feb. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Burnham D, Joeffry S, and Rice L, Computer-and Human-Directed Speech Before and After Correction. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Stent AJ, Huffman MK, and Brennan SE, “Adapting speaking after evidence of misrecognition: Local and global hyperarticulation,” Speech Commun., vol. 50, no. 3, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kulkarni RG et al. , “Hyperarticulation Detection in Repetitive Voice Queries Using Pairwise Comparison for Improved Speech Recognition,” in IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 2017, pp. 4985–4989. [Google Scholar]