Abstract

Background: Cervical cytology in postmenopausal women is challenging due to physiologic changes of the hypoestrogenic state. Misinterpretation of an atrophic smear as atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance (ASCUS) is one of the most common errors. We hypothesize that high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing may be more accurate with fewer false positive results than co-testing of hrHPV and cervical cytology for predicting clinically significant cervical dysplasia in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of 924 postmenopausal and 543 premenopausal women with cervical Pap smears and hrHPV testing. Index Pap smear diagnoses (ASCUS or greater vs. negative for intraepithelial lesion) and hrHPV testing results were compared with documented 5-year clinical outcomes to evaluate sensitivity and specificity of hrHPV compared with co-testing. Proportions of demographic factors were compared between postmenopausal women who demonstrated hrHPV clearance versus persistence.

Results: The prevalence of hrHPV in premenopausal and postmenopausal women was 41.6% and 11.5%, respectively. The specificity of hrHPV testing (89.6% [87.4–91.5]) was significantly greater compared with co-testing (67.4% [64.2–70.4]) (p < 0.05). A greater proportion of women with persistent hrHPV developed cervical intraepithelial lesion 2 or greater (CIN2+) compared with women who cleared hrHPV (p = 0.012). No risk factors for hrHPV persistence in postmenopausal women were identified.

Conclusion: Our data suggest that hrHPV testing may be more accurate than co-testing in postmenopausal women and that cytology does not add clinical value in this population. CIN2+ was more common among women with persistent hrHPV than those who cleared hrHPV, but no risk factors for persistence were identified in this study.

Keywords: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, human papillomavirus, Papanicolaou test, sensitivity and specificity

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer worldwide. In the United States (U.S.), there is an incidence and mortality of 7.7 and 2.3 per 100,000 women, respectively.1,2 High-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is a critical factor for cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer development, and hrHPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for 50% of clinically significant cervical dysplasia and 70% of cervical cancers.3,4 Risk factors for hrHPV persistence and cervical cancer include the following: smoking, early age at sexual debut, increasing numbers of sexual partners, co-infection with other sexually transmitted infection, and immunosuppression.5,6

Incorporation of Pap smear screening into clinical practice in the 1960s led to a dramatic decrease in the incidence and mortality of cervical carcinoma.7 The sensitivity of the Pap smear is now complemented by co-testing for hrHPV in women ages 30 and older.8 National guidelines in the United States allow for co-testing, cytology only, or primary hrHPV testing in women 30 years and older.9,10 Pap smears pose unique challenges for the cytopathologist due to hypoestrogenic changes of menopause making it difficult to ascertain atrophic hypocellular changes from other pathologic states.11

Misdiagnosis of an atrophic smear as a malignant smear is uncommon; misinterpretation of an atrophic smear as atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance (ASCUS) is one of the most common errors and can lead to unnecessary clinical follow-up and testing due to more false positive results.11,12 It has been shown that primary HPV DNA screening with cytology triage is more specific than conventional cytology screening.13

Atrophic smears may also lead to more false negative results. Studies outside the United States have investigated the role of Pap smears in older women and have shown that the sensitivity of cervical cytology in detecting moderate-to-severe cervical dysplasia declines with increasing age.14,15 A Swedish study found that more than half of HPV-positive postmenopausal women with clinically significant cervical dysplasia on colposcopy had normal cytology.16 Another study showed that despite a low prevalence of HPV in women older than 60 years, the risk of cervical dysplasia was high if they also tested positive in a second HPV test, and dysplasia was not detected by cytology in the majority of cases.17 A French study showed hrHPV was more sensitive, but less specific than cytology in the detection of cervical intraepithelial lesion grade 2 or greater (CIN2+) lesions among postmenopausal women.18

To our knowledge, the accuracy and specificity of hrHPV screening have not been examined specifically in postmenopausal women in the United States.

This article will evaluate the role of cytology and hrHPV testing in a cohort of U.S. postmenopausal women, describe the prevalence of abnormal Pap smears and hrHPV in a cohort of postmenopausal women undergoing cervical cancer screening at our institution from 2008 to 2013, and discuss the utility of cervical cytology and hrHPV testing in identifying clinically actionable (CIN2+) lesions. We hypothesize that hrHPV testing will be a better predictor than cytology for the detection of clinically significant cervical dysplasia in postmenopausal women. We will also evaluate factors associated with persistent hrHPV in this postmenopausal population.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective chart review was performed for women undergoing Pap smear with hrHPV testing at our institution, which uses Hybrid Capture 2 (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, Maryland) for hrHPV testing. We utilized a pre-existing Pap smear database, and patients were included if they underwent Pap smear with hrHPV testing at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) between 2008 and 2013, had a uterine cervix, and were age 30 years of age or older. Patients were excluded if they had undergone hysterectomy, had undergone radiation therapy with fields including the uterine cervix or vagina, could not be definitively categorized as premenopausal or postmenopausal, had an indeterminate index hrHPV result, or had an unsatisfactory index Pap smear result. This study was approved by the OHSU Institutional Review Board.

The index Pap smear time point was the date of Pap smear with hrHPV testing in 2008–2013, and the follow-up time points were any result that occurred after the index time point. Results were recorded for index Pap smear and hrHPV testing; prior Pap smear, hrHPV testing, and cervical pathology; and all follow-up Pap smear, hrHPV testing, and cervical pathology that were available during the 5 years following the index time point. Colposcopic impressions and associated biopsies were recorded for all time points when available. The primary outcome was the development of CIN2+ within 5 years after the index time point. Index Pap smear diagnoses (ASCUS or greater vs. negative for intraepithelial lesion) and hrHPV testing results were compared with documented 5-year clinical outcomes.

For all patients, data were collected regarding menopausal status, smoking history, insurance status, partner status, and race. Patients were determined to be postmenopausal if it was found to be documented in a provider note that they had undergone menopause before the index time point. For postmenopausal patients, age at menopause, history of abnormal Pap smear, sexual activity, partner status, number of sexual partners, history of prior sexually transmitted infection, and immune status were also recorded if that information was available in provider notes during chart review. History of atopic dermatitis was also recorded based on a study showing an association between atopic dermatitis and cervical hrHPV infection in adult women.19

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at OHSU.20,21 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the cohort as a whole and to analyze subgroups by Pap smear result, index hrHPV result, and persistence of hrHPV positivity. A two-tailed t-test and z-tests of proportions were conducted comparing index characteristics of the postmenopausal and premenopausal cohorts.

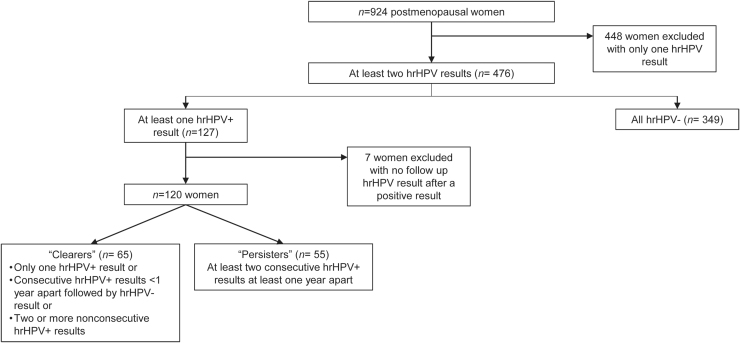

A subgroup analysis comparing hrHPV “persisters” to “clearers” was conducted to evaluate for factors related to hrHPV persistence among postmenopausal women. Women were included in this subgroup if they had at least two hrHPV results recorded and at least one positive result. Women were excluded from this subgroup if they did not have any positive hrHPV result or if they did not have any follow-up result recorded after a positive result.

“Persisters” were defined as those patients with two consecutive positive hrHPV results at least 1 year apart. “Clearers” were defined as those patients with (1) only one positive hrHPV result followed by a negative hrHPV result, (2) consecutive positive hrHPV results <1 year apart followed by a negative result, or (3) two or more nonconsecutive positive hrHPV results. To evaluate for factors related to hrHPV persistence and development of CIN2+, proportions of demographic factors were compared with two-sided χ2 tests or two-sided Fisher's exact tests. All analyses were conducted with the use of Stata software, version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

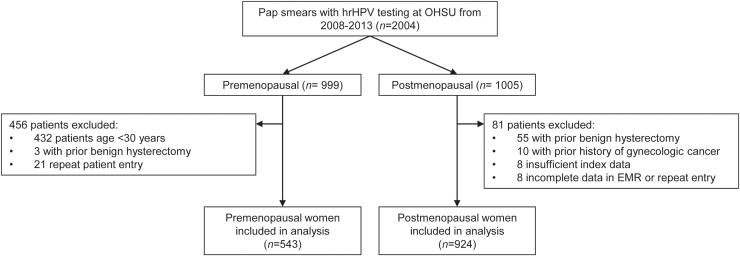

There were 2,006 women who underwent Pap smear with hrHPV testing at OHSU from 2008 to 2013, and 1,467 women met inclusion criteria with 543 premenopausal and 924 postmenopausal women included in the final data analysis (Fig. 1). The median ages at the time of index Pap smear and hrHPV testing were 37 years (range 30–59 years) in the premenopausal cohort and 60 years (range 42–74 years) in the postmenopausal cohort (Table 1). The prevalence of hrHPV was 22.6% among all women, 41.6% among premenopausal women, and 11.5% among postmenopausal women.

FIG. 1.

Study inclusions and exclusions.

Table 1.

Index Cervical Cytology Results, Index High-Risk HPV Results, and Select Demographic Data by Menopausal Status

| Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at study initiation, median years (range) | 37 (30–59) | 60 (42–74)* |

| Index Pap smear | 543 | 924 |

| NILM/benign, n (%) | 149 (27.4) | 657 (71.1) |

| Abnormal, n (%) | 394 (72.6) | 267 (28.9)* |

| ASCUS, n (%) | 372 (68.5) | 256 (27.7) |

| AGUS, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) |

| LSIL/CIN 1, n (%) | 12 (2.2) | 7 (0.8) |

| ASC-H, n (%) | 7 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| HSIL/CIN2–3, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Index hrHPV, n (%) | 543 | 924 |

| Negative, n (%) | 317 (58.4) | 818 (8.5) |

| Positive, n (%) | 226 (41.6) | 106 (11.5) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian | 3 (0.6) | 6 (0.6) |

| Asian | 34 (6.3) | 56 (6.1) |

| Black | 14 (2.6) | 33 (3.6) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.2) | 2 (2.2) |

| White, Hispanic | 14 (2.6) | 18 (1.9) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 464 (85.5) | 794 (85.9) |

| Multiracial | 4 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.7) | 9 (1.0) |

| Former or current smoker, n (%) | 189 (34.8) | 362 (39.2) |

| Married or partnered, n (%) | 286 (52.7) | 517 (56.0)* |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 33 (6.1) | 31 (3.4)* |

p < 0.05 comparing postmenopausal to premenopausal women by a two-tailed t-test.

AGUS, atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; hrHPV, high-risk HPV; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.

Patients were primarily white (85.8%), and the distribution of race was similar between the premenopausal and postmenopausal cohorts. There were similar rates of smoking between the two groups, 34.8% among premenopausal women and 39.2% among postmenopausal women. There were more postmenopausal women (56.0%) than premenopausal women (52.7%) who were married or partnered (p < 0.05). There was a greater rate of atopic dermatitis among the premenopausal group (6.1%) than the postmenopausal group (3.4%) (p < 0.05).

There were fewer postmenopausal (28.9%) than premenopausal women (72.6%) with an abnormal Pap smear result of ASCUS or greater. Among the 267 postmenopausal women with an abnormal index Pap smear, 76.0% were hrHPV negative and 24.0% were hrHPV positive. Most of these abnormal postmenopausal Pap smear results were ASCUS (95.9%), and only 29.3% were hrHPV positive. The remaining Pap smear results were atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance (AGUS) (4) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (7) (Table 1). Only three women were noted to have HIV, and none went on to develop CIN2+.

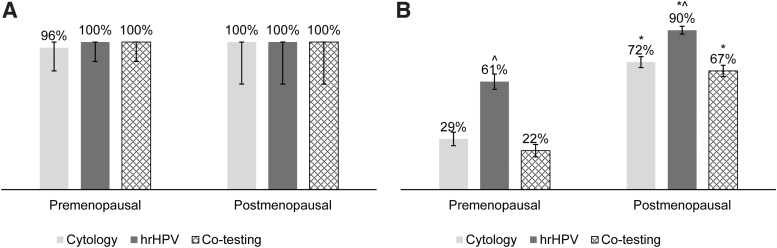

In this cohort, there were no significant differences in sensitivity of cytology, hrHPV, or co-testing between the postmenopausal and premenopausal cohorts. Specificity of cytology, hrHPV, and co-testing were greater in the postmenopausal cohort (p < 0.05). In both cohorts, specificity was greater for hrHPV than for co-testing (p < 0.05). All clinically actionable (CIN2+) lesions were correctly identified by both hrHPV and by co-testing (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of cytology, hrHPV, and co-testing of cytology and hrHPV with 95% confidence intervals. (A) There was no difference in sensitivity between postmenopausal and premenopausal women for cytology alone, hrHPV, or co-testing. (B) Specificity for cytology alone, hrHPV, and co-testing was significantly different when comparing postmenopausal and premenopausal cohorts. hrHPV was more specific than co-testing among postmenopausal women. *p < 0.05 comparing postmenopausal to premenopausal women. ^p < 0.05 comparing hrHPV to cytology alone and co-testing.

There were 476 postmenopausal women with at least two consecutive hrHPV results, and 127 had at least one positive hrHPV result and were included in the subgroup analysis for hrHPV persistence. Of the latter, seven women did not have any follow-up hrHPV test after a positive result and were excluded from subset analysis. Of the 120 women in the final subgroup analysis, 65 were classified as “clearers” and 55 as “persisters” (Fig. 3). In this group, there were 22 clearers and 43 persisters who underwent colposcopy as part of their clinical workup. A significantly greater proportion of women with persistent hrHPV developed CIN2+ compared with women who cleared hrHPV (16% vs. 3%, respectively, p = 0.022). There was no demographic factor that was associated with hrHPV persistence. Demographic data for hrHPV clearers compared with persisters are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 3.

Inclusions and exclusions for a subgroup analysis of “clearers” and “persisters” to evaluate for factors related to persistence of hrHPV among postmenopausal women. hrHPV, high-risk HPV.

Table 2.

Demographic Factors and High-Risk HPV Persistence Among Postmenopausal Women

| Clearersa(n = 65) | Persistersb(n = 55) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max diagnosis CIN2+, n (%) | 2 (3) | 9 (16) | 0.022* |

| History of abnormal Pap, n (%) | 41 (63) | 39 (71) | 0.364 |

| Former or current smoker, n (%) | 28 (43) | 24 (44) | 1.000 |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 1 (2) | 4 (7) | 0.178 |

| History of STI, n (%) | 18 (28) | 14 (25) | 0.838 |

| 5 or more lifetime partners, n (%) | 10 (15) | 11 (20) | 0.631 |

| Sexually active at index, n (%) | 31 (48) | 31 (56) | 0.344 |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 9 (14) | 9 (16) | 0.799 |

p < 0.05 comparing persisters to clearers by use of two-tailed chi-square test or two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Women with (1) only one positive hrHPV result followed by a negative hrHPV result, (2) consecutive positive hrHPV results <1 year apart followed by a negative hrHPV result, or (3) two or more nonconsecutive positive hrHPV results.

Women with at least two consecutive hrHPV positive results at least 1 year apart.

CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial lesion 2 or greater; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Discussion

Cervical cytology may not be as clinically useful as hrHPV in postmenopausal women. Older women with normal cytology are often hrHPV positive with clinically significant cervical dysplasia, and normal, atrophic postmenopausal Pap smears are often incorrectly characterized as ASCUS.11,14,16 Primary hrHPV screening, cytology alone, and co-testing are accepted options for cervical cancer screening according to U.S. national guidelines for women 30 years and older. However, there are no specific guidelines for postmenopausal women, and the screening test used remains the physician's decision.9,10 The challenges with atrophic Pap smears are thought to be related to the hypoestrogenic state of menopause and its impact on the squamous cells of the cervix; thus, the use of Pap smears in the postmenopausal population may lead to more unnecessary follow-up Pap smears and clinical follow-up.12

Previously published studies largely come from European populations and have used arbitrary age cutoffs such as 50, 55, or 60 years to compare hrHPV and cytology results between older and younger women.13,16,17,22 One study has compared hrHPV and cytology among postmenopausal women without comparing to a premenopausal cohort.18 To our knowledge, this is the first U.S. study to compare cervical cytology and hrHPV testing by menopausal status rather than an arbitrary age cutoff.

The prevalence of hrHPV in our entire cohort of both premenopausal and postmenopausal women was 22.6%, which parallels that of the U.S. population (20.4%).23 Previously published postmenopausal hrHPV studies have been performed largely in European populations, where hrHPV rates for the entire population have been found to range from as low as 2.2% to as high as 22.8%.3

The prevalence of hrHPV among postmenopausal women in our cohort was 11.5%. Previously published studies have reported varying rates of hrHPV in older women, ranging from 1% to 9.9% with variable ages of women included.22 Gyllensten et al., a retrospective study of Swedish women ages 55–74, reported an hrHPV prevalence of 6.2%; Ferenczy et al. reported rates as low as 1% among 306 women in Quebec ages 50–70; in a Swedish study of 1,051 women ages 60–89, the authors found a prevalence of 4.1%; a prospective Finnish study of over 10,000 women showed a prevalence of 4.9% among women 55 years of age and older; and a French study of 406 postmenopausal women showed a prevalence of 9.9%.13,16–18,22

It is important to note that these other studies were performed in Canadian or European populations, where hrHPV testing techniques and screening programs varied among studies that were performed over the last two decades. The marginally higher prevalence in our postmenopausal cohort may be reflective of an overall higher hrHPV prevalence in the United States compared to Europe or intrinsic risk within our cohort. In addition, our institution is a referral center, which may explain why our postmenopausal hrHPV prevalence falls near the upper limits of this established range and why there was a relatively high prevalence of hrHPV and abnormal Pap smear results in our premenopausal cohort.

hrHPV had a significantly greater specificity (89.6%) than either cervical cytology alone (72.0%) or co-testing (67.4%) in our postmenopausal cohort and correctly identified all women with CIN2+. These results are in agreement with other studies that have shown greater specificity of hrHPV testing compared to Pap smear in older women.16,17 However, a French study of postmenopausal women showed lower specificity of hrHPV testing (25%) compared to Pap smear (80%) for detecting CIN2+ in postmenopausal women; one possible reason for the higher specificity of cytology is the high rate of hormone replacement therapy of 46% in this study.18

Our results showed no difference in the sensitivity of cervical cytology, hrHPV testing, or co-testing (100%). Some studies have instead demonstrated low sensitivity of cervical cytology in the detection of clinically significant cervical dysplasia among older women.15,17,18 In a study by Gustafsson et al., it was found that despite substantial Pap smear collection and a relatively high incidence of invasive cervical cancer above the age of 50, the probability of detecting cancer in situ decreased markedly from 35 to 50 years of age and remained low thereafter.14

It is important to note that while CIN lesions may not be detected, postmenopausal Pap smears still tend to be characterized as ASCUS when they are atrophic.12 Our data favor a greater number of falsely mildly abnormal results with 96% of abnormal postmenopausal Pap smears being ASCUS, 70% of which were hrHPV negative. These results suggest that the cytology component of co-testing does not add clinical value among postmenopausal women and may increase follow-up procedures and referrals due to false positive results without detecting any additional clinically significant disease.

hrHPV testing tends to be less specific in younger women as a result of clearance of hrHPV infections by the immune system and spontaneous regression of lower grade dysplasia.24 Our data show that hrHPV testing was significantly more specific in the postmenopausal than the premenopausal cohort. Accepted methods for cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older include cervical cytology every 3 years, co-testing every 5 years, or hrHPV every 3 years, and our study suggests primary hrHPV screening may be the best strategy among postmenopausal women. Of note, both cytology and co-testing were found to be more specific in postmenopausal than in premenopausal women; however, hrHPV testing remained more specific than cytology and co-testing in both cohorts. There was no significant difference in sensitivity of cytology, hrHPV testing, or co-testing between postmenopausal and premenopausal women.

The rate of hrHPV persistence in our postmenopausal cohort was 45.8%, which is higher than that observed in younger women.25 As expected, CIN2+ was more common among women with persistent hrHPV than among those who cleared hrHPV. No risk factors for persistence were identified in this study. Known risk factors for hrHPV persistence and progression to cervical cancer in the general population include smoking, early age at sexual debut, increasing numbers of sexual partners, co-infection with other sexually transmitted infection, and immunocompromise.5,6 There is a paucity of data regarding risk factors for hrHPV persistence specifically among postmenopausal women. Our results could be the consequence of the relatively small sample size of the subset analysis, so future work should seek to prospectively identify risk factors for persistence in a larger group of postmenopausal women.

Strengths of the study include the analysis by documented menopausal status rather than an arbitrary age cutoff, the comparison of the postmenopausal cohort to a premenopausal cohort, and the substantial overall sample size, which included 924 postmenopausal women.

Limitations to this study include its retrospective nature, small numbers of CIN2+, and lack of data regarding hormonal therapy at menopause. In addition, it was found during thorough chart review that demographic data points were not consistently recorded or updated in the medical record. It is unknown whether race was self-identified. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, which included collecting data available in the electronic medical record in the 5-year time period following the index cytology and hrHPV result, it is unknown which women did not follow up as recommended or left the system with follow-up elsewhere, and the sample size was relatively small for the hrHPV persistence risk factor analysis.

Conclusion

Multiple studies support that hrHPV testing alone is more sensitive than cytology screening for CIN2+ lesions in postmenopausal women and have even suggested that co-testing of hrHPV and cervical cytology is not more sensitive than hrHPV testing, alone.15,16 These findings come largely from studies performed using data from a cohort of women in single region of Sweden. While larger prospective studies have been conducted in Europe, these results have not been replicated outside of this population or in a U.S. population, making the findings poorly generalizable to other countries or health care systems.

Our results were in alignment with these findings, and our data support greater specificity of hrHPV testing compared with cytology and with co-testing. Furthermore, upon examination of all abnormal postmenopausal Pap smear results, almost all (96%) were ASCUS, and 71% were negative for hrHPV. Thus, the Pap smear was less effective at triaging women for shorter interval follow-up testing.

Our study supports the use of primary hrHPV testing to screen for clinically significant cervical dysplasia. Future studies should prospectively evaluate whether co-testing should be replaced by primary hrHPV testing in postmenopausal women.

Authors' Contributions

J.M.K.: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and writing—original draft. M.C.: data curation and writing—original draft. M.E.L.: data curation. E.G.M.: writing—review and editing. T.K.M.: conceptualization and methodology. A.S.B.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, and methodology.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR002370. Support for this article was provided, in part, by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed in this study do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. This study was conducted at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, OR.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:393–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ward E, Sherman RL, Henley SJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1999–2015, featuring cancer in men and women ages 20–49. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:1279–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Vuyst H, Clifford G, Li N, Franceschi S. HPV infection in Europe. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2009;45:2632–2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999;189:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical C. Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer 2007;120:885–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim HS, Kim TJ, Lee IH, Hong SR. Associations between sexually transmitted infections, high-risk human papillomavirus infection, and abnormal cervical Pap smear results in OB/GYN outpatients. J Gynecol Oncol 2016;27:e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gustafsson L, Pontén J, Zack M, Adami HO. International incidence rates of invasive cervical cancer after introduction of cytological screening. Cancer Causes Control 1997;8:755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright TC Jr., Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D.. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:346–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: Interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol 2015;136:178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24:102–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tabrizi A. Atrophic Pap smears, differential diagnosis and pitfalls: A review. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci 2018;6:2–5 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gupta S, Sodhani P. Reducing “atypical squamous cells” overdiagnosis on cervicovaginal smears by diligent cytology screening. Diagn Cytopathol 2012;40:764–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leinonen M, Nieminen P, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, et al. Age-specific evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening vs conventional cytology in a randomized setting. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1612–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gustafsson L, Sparen P, Gustafsson M, et al. Low efficiency of cytologic screening for cancer in situ of the cervix in older women. Int J Cancer 1995;63:804–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gyllensten U, Lindell M, Gustafsson I, Wilander E. HPV test shows low sensitivity of Pap screen in older women. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:509–510; author reply 510–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gyllensten U, Gustavsson I, Lindell M, Wilander E. Primary high-risk HPV screening for cervical cancer in post-menopausal women. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125:343–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hermansson RS, Olovsson M, Hoxell E, Lindstrom AK. HPV prevalence and HPV-related dysplasia in elderly women. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tifaoui N, Maudelonde T, Combecal J, et al. High-risk HPV detection and associated cervical lesions in a population of French menopausal women. J Clin Virol 2018;108:12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morgan T, Hanifin J, Mahmood M, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with cervical high risk human papillomavirus infection. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2015;19:345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferenczy A, Gelfand MM, Franco E, Mansour N. Human papillomavirus infection in postmenopausal women with and without hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, Unger ER, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Sanjosé S, Brotons M, Pavón MA. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;47:2–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]