Abstract

We present the case of a patient with granulomatous endocarditis of the mitral valve leading to severe valve stenosis caused by granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Endocarditis is a rare complication of granulomatosis with polyangiitis that may be misdiagnosed as infectious endocarditis or, as in our case, thrombotic lesions. (Level of Difficulty: Intermediate.)

Key Words: autoimmune, echocardiography, endocarditis, mitral valve, thrombosis, stenosis

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; IE, infectious endocarditis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MV, mitral valve; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography

Graphical abstract

History of Presentation

A 53-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department because of progressive shortness of breath, chest pain, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and elevated C-reactive protein. His permanent medication included phenprocoumon and immunosuppressants (methotrexate and prednisolone) because of a suspected but so far not confirmed myeloperoxidase (MPO)/antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated small vessel vasculitis. Methotrexate had been discontinued by the patient a few weeks before because he feared adverse events. At admission, vital parameters were stable with a blood pressure of 124/82 mm Hg, pulse of 70 beats/min, breathing frequency 16 breaths/min, and normal body temperature. Physical examination showed a livedo racemosa and mild scleritis; heart and lung sounds were normal.

Learning Objectives

-

•

To illustrate an interdisciplinary diagnostic workup for patients with GPA and endocarditis.

-

•

To recall common differential diagnoses of valvular manifestations in patients with GPA.

-

•

To list common antibodies associated with both granulomatous and subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Medical History

The patient’s medical history included apparent ear, nose, and throat involvement typical of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), scleritis, polyneuropathy, colitis, livedo, and weight loss. Five years earlier, the patient had undergone aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve because of suspected endocarditis.

Differential Diagnosis

Given the patient’s history of infectious endocarditis (IE), the initial concern was for endocarditic valve involvement. The findings were unspecific for other common differential diagnoses such as congestive heart failure, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, or coronary heart disease.

Investigations

The patient’s C-reactive protein level was 56.3 mg/l, leukocyte count was 9.34 × 10⁹/l, procalcitonin was <0.05 μg/l, creatinine was 79 μmol/l, blood urea nitrogen was 5.2 mmol/l, and international normalized ratio was 1.8. Chest radiograph showed no signs of pathological findings.

For reasons of differential diagnostics regarding the patient’s dyspnea and chest pain, a bed-side transthoracic echocardiography was performed, which revealed a thickened native mitral valve (MV) with several vegetations on the MV ring and both mitral leaflets plus turbulent flow across the valve (Video 1). In the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), these vegetations were up to 8 × 13 mm in size and presented thrombus-like without associated mobility. No growth was noted on blood cultures.

Management (Medical/Interventions)

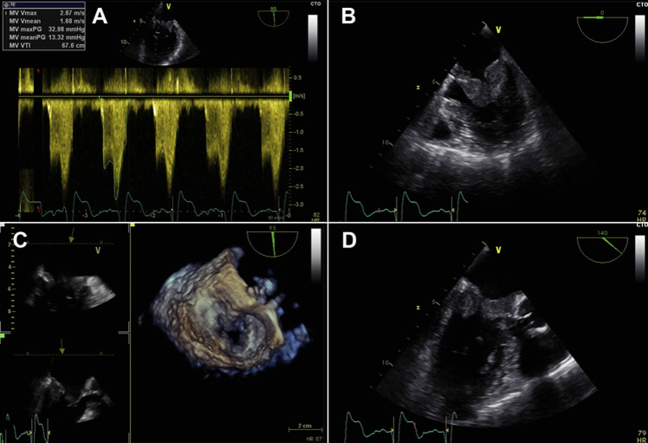

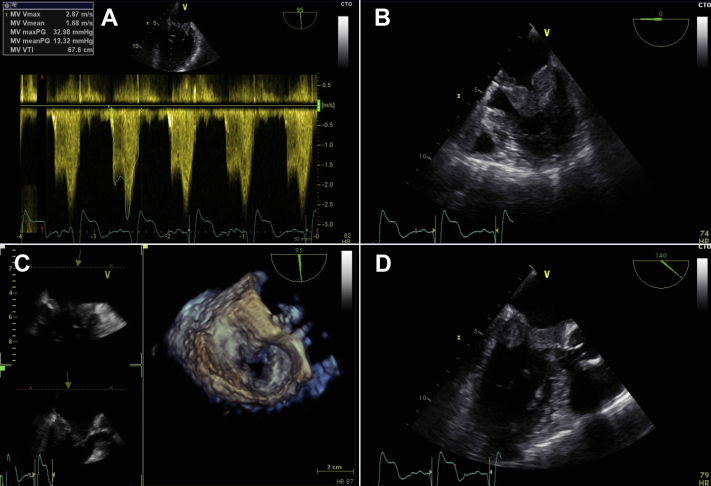

Apart from the findings on the MV, the patient did not meet any further Duke Criteria. Thus, no antibiotic treatment was started. The patient received therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin and phenprocoumon. A follow-up TEE 5 days later showed progressive thrombus-like vegetations that now included the subvalvular regions and the aortic-mitral continuity (Videos 2, 3, and 4). The MV was relevantly stenotic (maximum gradient 33 mm Hg, mean gradient 13 mm Hg, MV area 1.3 cm2, and heart rate of 82 beats/min) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transesophageal Echocardiography of the Mitral Valve

(A to D) Echocardiographic presentation of gelatinous deposits on the anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflet resulting in an increased transvalvular pressure gradient of 13 mm Hg as well as reduced valve area of 1.3 cm2.

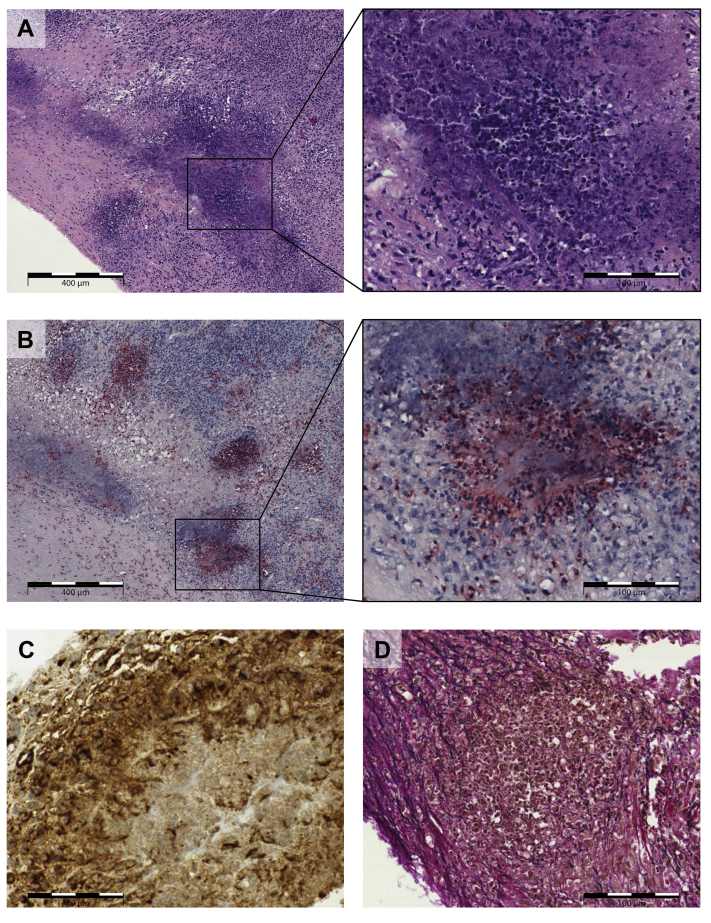

After discussion in the interdisciplinary heart team conference, the patient’s MV was surgically replaced. Histology of the native MV showed a severe chronic and active necrotizing granulomatous endocarditis with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histological and Immunohistochemical View of the Mitral Valve Resectate

(A) Pronounced destruction of the valve stroma by inflammatory cell infiltrates and geographic, granulocyte-rich necrosis (see enlargement); hematoxylin-eosin staining. (B) Poorly delineated granulomas with central neutrophilic microabscesses, neutrophilic granulocytes marked in red; ASD-CL (naphthol AS-D chloroacetate) staining. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of granuloma with CD68-positive macrophages (brown). (D) Inflammatory destruction of the elastic valve stroma (elastic fibers in black); Elastica van Gieson staining.

Results of microbiologic cultures of the native MV remained negative, as did follow-up blood cultures. A sterile granulomatous endocarditis was finally diagnosed. Based on a review of the patient’s medical history, presence of MPO-ANCA, and the biopsy results showing granulomatous endocarditis, the clinical diagnosis of an MPO-ANCA–positive GPA was made. The patient received induction treatment with corticosteroids and a combination of cyclophosphamide and rituximab, followed by maintenance treatment with rituximab, which led to remission of symptoms.

Discussion

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is a systemic vasculitis of small and medium vessels. In addition to vasculitis, extravascular necrotizing granulomas can occur. Cardiac manifestations affect ∼3% to 44% (1) of patients, with perimyocarditis being the most frequent manifestation. We present the case of a patient with symptomatic mitral stenosis due to acute granulomatous necrotizing endocarditis of the MV.

Cardiac manifestation of GPA predominantly affects the aortic valve rather than the MV and usually leads to valve regurgitation (2). MPO-ANCA–positive (rather than PR3-ANCA–positive) GPA is seen in ∼5% of the cases, often differing in its clinical cause from PR3-ANCA–positive GPA (3). The literature describes several cases of ANCA-positive IE with a wide variety of clinical presentations, making a clear differential diagnosis between infectious and noninfectious ANCA-positive endocarditis challenging (4). Differentiating IE from noninfectious entities may be especially difficult when classical signs of infection such as fever are missing and when blood culture results remain false-negative. In both conditions, patients may present with elevated inflammatory markers.

Both entities can present with similar cardiac, renal, and pulmonary findings, as well as overlapping dermatologic vasculitic presentations, ANCA positivity, and resembling constitutional signs.

Valvular involvement of GPA usually requires valve replacement; there are only a few cases known in which immunosuppressive therapy led to complete decline of the valvular lesions (2). Usually only one valve is affected, but there have been reports of multiple valve involvement (5). The usually distinctive scarring of endocardial tissue makes successful nonsurgical treatment options and valve repair unlikely.

Although GPA-associated valvular lesions usually present endocarditis-like (2), this case documents a relevant MV stenosis due to endocardial involvement with GPA. The clinical presentation resembled a case of rapidly progressive MV thrombosis with impending risk of embolism.

Histological findings are often nonspecific inflammation, although necrosis and microabscesses have been reported (6). Neutrophils are the main effector cells in GPA-associated lesions, typically activated by ANCA (7). In our case, there was a geographic, granulocyte-rich necrosis with granulomatous demarcation.

Follow-Up

The patient’s further course was uneventful. He made a full recovery and was discharged to a rehabilitation center. Current medication consists of rituximab and prednisolone. He is still in remission.

Conclusions

IE mimicking clinical manifestations of GPA has to be considered as a differential diagnosis in GPA patients presenting with endocarditis (8). Subacute bacterial endocarditis is also especially associated with c-ANCA and less frequently with p-ANCA, anti-PR3, and anti-MPO (9). Both IE and rheumatic endocarditis usually lead to insufficiency of the valve rather than to stenosis but have different treatment approaches. Treating a presumed GPA with rituximab and cyclophosphamide for a patient who actually has IE can be deleterious. The literature regarding treatment of ANCA-positive IE (i.e., whether to use antibiotics alone or a combination of antibiotics and steroids) is currently not consistent (4).

Our case presentation emphasizes the high grade of suspicion in clinical and diagnostic workup (including microbiological, immunological, and histological data) necessary to establish the correct diagnosis in a patient presenting with endocarditis and GPA.

Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary Material

TTE 4 chamber view - TTE 4 chamber view with color doppler showing turbulent flow and a big flow convergence zone.

TEE at 0 degrees - TEE view at 0 degrees of the mitral valve showing vegetations.

TEE at 105 degrees - TEE view at 105 degrees of the mitral valve with color doppler showing turbulent flow and a big flow convergence zone.

TEE 3D view - 3D-TEE view of the mitral valve.

References

- 1.McGeoch L., Carette S., Cuthbertson D. Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1209–1212. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacoste C., Mansencal N., Ben M'rad M. Valvular involvement in ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis: a case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer J.H., Wright M.N., Herrmann K. Myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) is a clinically distinct subset of ANCA-associated vasculitis: a retrospective analysis of 315 patients from a German Vasculitis Referral Center. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2953–2963. doi: 10.1002/art.39786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bele D., Kojc N., Perse M. Diagnostic and treatment challenge of unrecognized subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with ANCA-PR3 positive immunocomplex glomerulonephritis: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:40. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-1694-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koyalakonda S.P., Krishnan U., Hobbs W.J. A rare instance of multiple valvular lesions in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis. Cardiology. 2010;117:28–30. doi: 10.1159/000319603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruno P., Le Hello C., Massetti M. Necrotizing granulomata of the aortic valve in Wegener's disease. J Heart Valve Dis. 2000;9:633–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kallenberg C.G., Heeringa P., Stegeman C.A. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis and treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitides. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:661–670. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi H.K., Lamprecht P., Niles J.L., Gross W.L., Merkel P.A. Subacute bacterial endocarditis with positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-proteinase 3 antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:226–231. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<226::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahr A., Batteux F., Tubiana S. Brief report: prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in infective endocarditis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1672–1677. doi: 10.1002/art.38389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TTE 4 chamber view - TTE 4 chamber view with color doppler showing turbulent flow and a big flow convergence zone.

TEE at 0 degrees - TEE view at 0 degrees of the mitral valve showing vegetations.

TEE at 105 degrees - TEE view at 105 degrees of the mitral valve with color doppler showing turbulent flow and a big flow convergence zone.

TEE 3D view - 3D-TEE view of the mitral valve.