Abstract

The Delphi technique is a systematic process of forecasting using the collective opinion of panel members. The structured method of developing consensus among panel members using Delphi methodology has gained acceptance in diverse fields of medicine. The Delphi methods assumed a pivotal role in the last few decades to develop best practice guidance using collective intelligence where research is limited, ethically/logistically difficult or evidence is conflicting. However, the attempts to assess the quality standard of Delphi studies have reported significant variance, and details of the process followed are usually unclear. We recommend systematic quality tools for evaluation of Delphi methodology; identification of problem area of research, selection of panel, anonymity of panelists, controlled feedback, iterative Delphi rounds, consensus criteria, analysis of consensus, closing criteria, and stability of the results. Based on these nine qualitative evaluation points, we assessed the quality of Delphi studies in the medical field related to coronavirus disease 2019. There was inconsistency in reporting vital elements of Delphi methods such as identification of panel members, defining consensus, closing criteria for rounds, and presenting the results. We propose our evaluation points for researchers, medical journal editorial boards, and reviewers to evaluate the quality of the Delphi methods in healthcare research.

Keywords: Delphi studies, Quality tools for methodology, Research methods, Delphi technique, Consensus, Expert panel, Coronavirus disease 2019, SARS-CoV-2

Core Tip: There are no standard quality parameters to evaluate Delphi methods in healthcare research. Delphi methods’ vital elements include anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, and statistical stability of consensus. Published studies have used modified versions of Delphi, and details on methods like expert panel selection, defining consensus, or closing criteria for Delphi rounds are not explicit. We suggest quality assessment tools for readers and researchers for a systematic assessment of Delphi studies.

INTRODUCTION

This review used the “Delphi study” for the published studies that used Delphi methodology. “Delphi rounds” is used for the survey questionnaire rounds to develop iterative discussion among panel members. “Delphi process” is used for the steps of Delphi methods in research.

The term “Delphi” originated from ancient Greek mythology and was believed to be the precinct of Pythia (a major oracle), where prophecies were made to dictate and direct vital state affairs. In its literal sense, Delphi methods can be defined as a structured technique to modulate a group communication process effectively in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem[1]. The Delphi method was initially developed for business forecasting using an expert panel’s interactive discussion, assuming collective judgments are more valuable than individuals.

Possibly the first application of Delphi methodology was during the cold war in the 1950s by the United States army. They used it for their military project RAND to develop consensus among experts using repeated rounds of anonymous feedback, forecasting future enemy attacks[2]. After this first application, it has been used in many other academic domains like finance, economics, development planning, and healthcare, where group forecasting makes sense in the absence of accurate tested data. In modern times, this forecasting tool has evolved into a statistical methodology to collate individual opinions and converge them into statistically generated consensus with collective intelligence. A constant theme is observed across all domains with vital elements like anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, and group response (or consensus)[3].

The anonymity of individual members in a Delphi study removes the inherent bias like dominance and group conformity (defined as groupthink) observed with face-to-face group meetings. The primary purpose of the Delphi technique is to generate a reliable consensus opinion of a group of experts by an iterative process of questionnaire interspersed with controlled feedback[2]. After initial slow acceptance in healthcare, it is now a widely used method to generate group consensus, develop qualitative practice points, or identify future research areas. In healthcare, the Delphi process had been used in diverse areas: (1) Evaluate current knowledge; (2) Resolving controversy in management[4]; (3) Formulating theoretical or methodological guidelines[5,6]; (4) Developing assessment tools and indicators[7,8]; and (5) Formulating recommendations for action and prioritizing measures[9].

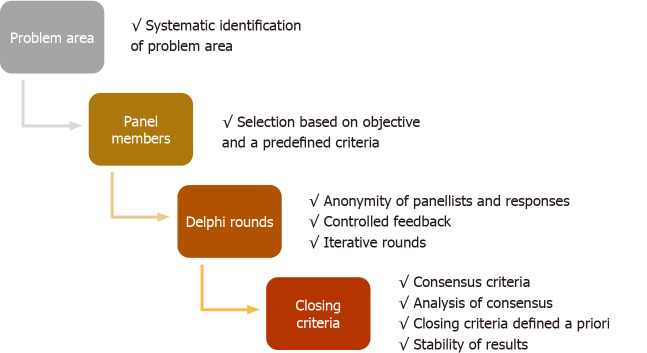

The Delphi methods from its inception have undergone modifications to structure effective and faster consensus. The modified Delphi does not have a standard criterion, but in principle, a steering group facilitates the group communication process effectively. There are no set standards for reporting Delphi studies in healthcare research, unlike other qualitative and quantitative clinical research tools. There are also no validated quality parameters to evaluate Delphi studies. In a recent meta-analysis of Delphi studies in healthcare research, many studies were found to be of questionable quality[10]. The protocol design, the definition of consensus, and closing criteria were not set a priori and vary widely in Delphi studies. There have been attempts to identify quality parameters to conduct and evaluate Delphi studies[10-12]. The guidance on conducting and reporting of Delphi studies (CREDES) is a popular tool, developed for Delphi studies on palliative care. The authors acknowledged significant variation in the reporting and methodology of Delphi studies and proposed CREDES standards for reporting and conducting such studies[12]. However, these tools are neither been validated in other fields of medicine nor universally accepted for the conduct of Delphi studies. The discrepancy in conduct and transparency of reporting may overshadow the consensus recommendations generated by Delphi studies. There is an urgent need of simple tools for systematic assessment of the quality of Delphi studies. Like other statistical research studies, readers must consider if the methodology has been followed appropriately for the key elements of Delphi technique. This article recommends critical appraisal of a Delphi study in healthcare sequentially by nine qualitative evaluation points in a four-step methodological process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stepwise quality assessment of Delphi studies.

PROBLEM AREA

The Delphi study is practical in problematic areas where either statistical model-based evidence is not available, knowledge is uncertain and incomplete, and human expert judgment is better than individual opinion[1]. The emerging disease or conditions in healthcare often simulates such areas, where either standard research pathways cannot be adopted or become impractical. Various approaches can identify these problem areas: (1) Extensive systematic literature search; (2) Group discussion among a defined steering group; and (3) Open-ended discussion rounds among panel members.

The process of identifying problem areas and its communication among all participating panel members should be explicit and must be done before the final survey rounds to achieve consensus.

Evaluation point

The criteria used to identify the problem area and process followed should be documented. The systematic search of the literature must mention period, keywords, and database included in the search.

PANEL MEMBERS

The members who participate in the anonymous voting process of the Delphi survey are called panelists. The panel member selection is undoubtedly the most crucial aspect of Delphi research studies[13]. The methods used for the identification and selection of panel members are discrepant in published Delphi studies. There are no standard criteria used for the definition of panel members[10]. The readers should consider the following issues while evaluating the Delphi study: Homogeneity of panel, labelling panel members as an ‘expert’, and size of the panel.

Homogeneity of the panel

A diverse panel helps to achieve a broader perspective and generalization of consensus. The homogenous group, on the other hand, may be more reliable in a particular study objective. The homogenous panel is suitable when resolving unsettled issues of a focused problem like management of acute respiratory distress syndrome, while the heterogeneous panel is appropriate in a broader situation like when studying the impact of mental illness. The methodology should represent the process followed for achieving homogeneity in the study.

Expert panel

The labelling of panel members as ‘experts’ is most contentious. The expert can be defined as someone with knowledge and experience on a particular subject matter; however, it is practically difficult to measure experience quantitatively. Despite its controversy, the experts are commonly used in the Delphi studies for panel members without a uniform selection criterion. The common goal behind using experts is to increase the qualitative strength of recommendations or consensus. The readers must evaluate the criteria for expert panel selection. Panel selection should adhere to a predefined criteria[4,6,14].

Size

There is no standard size of the panel members and varies from 10 to 1000 (typically between 10-100) in published studies. However, due to data management difficulties and logistic issues (rounds of the survey), a panel with three-digit sample size is unusual[10,15]. Generally, a double-digit number close to 30-50 is considered optimum in concluding rounds for a homogenous Delphi[4,14]. Appropriate size depends on the complexity of the problem, homogeneity (or heterogeneity) of the panel, and availability of the resources. Apart from panel members with knowledge, some studies recruit members from diverse academic and practice backgrounds or involve end-users in the process[16].

Generalizability of Delphi results requires an appropriate panel size, diverse representation of members from different specialties, and geographical distribution.

The electronic Delphi survey (also called e-Delphi) helps in the global representation of panel members, saves time, and fastens the survey rounds using technology without physical voting. This process involves selecting experts after research for eligibility on the world wide web; further email invitations to participate in the project can be sent. The acceptance rate among experts can be low, and researchers usually consider this higher attrition rate during the invitation process.

Evaluation point

The selection of a panel or voting members in a Delphi study should be based on objective and predefined criteria and related to the problem under study.

DELPHI ROUNDS

The strength of Delphi process is anonymity of panelist in the survey rounds, controlled feedback and iterative discussions. Anonymous survey rounds have advantages over face-to-face or group encounters in reducing dominance and group conformity. Participants feel more comfortable in providing anonymous opinions on uncertain, unsettled issues. The interpretation of items may sometimes become a critical issue in anonymous Delphi rounds and may affect the consensus process.

The “controlled feedback” is another classic characteristic of the Delphi study. It is termed as “controlled” because moderator decides about feedback provisions based on responses to the items and open comments. After each of the survey rounds, obtained data are analyzed and presented in an easily interpretable format to all the panel experts. It can include simple charts and statistics showing the stability of responses. Statistics usually include the measurement of central tendencies with dispersion, percentage, and frequency of distribution[17]. Even anonymous comments can be incorporated as a part of the feedback. Sometimes individual feedback along with group responses are also provided. Controlled feedback gives insight to the individual member about the trend and one can change its response if needed. Panel members should clear their position if they have an extreme choice of response in a particular situation.

Analysis of successive iterative rounds provides an opportunity to evaluate data for consensus and interspersed stability among the two successive rounds. The repetitive and interactive survey rounds are useful for gathering qualitative information, improving framing of the statements for panel members, and achieving consensus.

Evaluation point

The Delphi survey should be assessed for iterative discussions and controlled feedback while maintaining a strict anonymity of the panel members and their responses.

CLOSING CRITERIA

As Delphi is a method to generate consensus of individual panel member opinion on unsettled critical issues, the consensus and closing criteria vary widely among the studies[10,12,15]. The definition of consensus used in published Delphi studies is discrepant.

Consensus

Traditionally, a consensus is considered as the primary outcome of the Delphi study. However, its understanding is quite confusing among various studies. Consensus can mean a group opinion, solidarity towards a sentiment, or sometimes absolute alignment of the opinion of experts[18]. Hence, various measures have been used to define consensus. A meta-analysis[10] to evaluate quality of published Delphi studies found 73% of the studies reported a consensus method, and only 68% did so in an advanced declared protocol. It was even observed that some studies declare achieving consensus but do not provide the process to reach the consensus and its definition[10,12,15]. The definition of consensus used in published Delphi studies is discrepant[12,19]. The consensus definition used commonly is the percentage of agreement based on a predefined cut-off, central tendency, or a combination of both. However, percentage agreement varies widely from 50%-97% and is selected arbitrarily[10,12].

Closing criteria

The conventional design of the Delphi study had at least four rounds. However, the essence of good Delphi surveys is an iterative process and controlled feedback to generate consensus. The closing criteria in most of the Delphi studies include consensus achieved after a prefixed (usually two) rounds[10,12]. The stability of the responses or consensus cannot be checked with two rounds of Delphi. Any change in the items or controlled feedback may alter the response of panelists. However, these responses may not be stable and hence a fixed number of rounds without assessment of the stability of the results is a compromise on statistical robustness. The invention of “modified Delphi” arbitrarily uses two-three rounds of survey decided a priori as a closing criterion. The “modified” term in Delphi studies is, however, discrepant and without any universal accepted criterion. The only common thing in modified Delphi methodology is the active effort of the steering group in generating consensus. The steering group performed a systematic search of the literature in the problem area and, instead of open-end, initial Delphi rounds are focused on achieving consensus among panelists. The group also review the results after each round and items that reached consensus are dropped for the next rounds, but the items that are consistently not achieving consensus despite controlled feedback can also be dropped[20]. However, this active participation of the steering group can cause bias through opinion of members.

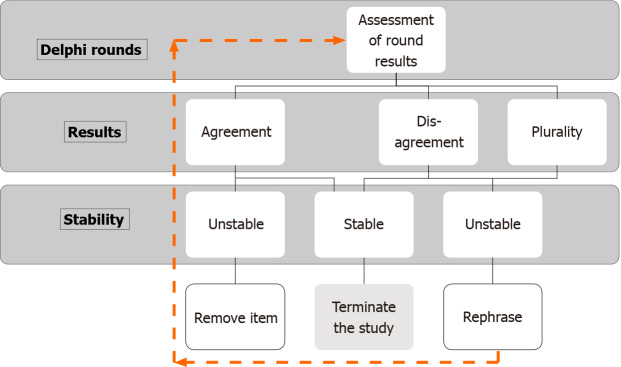

Stability

Understanding the stability of responses is even more confusing than consensus, and the stability of the consensus is rarely used in Delphi studies as a closing criterion. Classically, consensus or a pre-fixed round of surveys served as a closing criterion. It comes with an inherent risk that a significant change in responses occurred in the last round, affecting the stability of the results or consensus. Hence some authors believed that achieving a consensus is meaningless with unstable responses[1,21-23]. The stability of the results is thus considered the necessary criterion. Stability is defined as the consistency of responses between successive rounds of a study[21]. The researchers believe that specific results of two separate rounds for a particular question can occur by chance, which can be decreased by obtaining statistically significant stability (or variance) of the responses[10]. In other words, consensus can be there in unstable responses, and stability can be there without consensus, and hence achieving response stability should be an appropriate closing criterion. However, every effort to achieve consensus should be made[21,23]. Therefore, a hierarchical stopping criterion should be adopted as a closing criterion for Delphi (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stability assessment for Delphi rounds.

Evaluation point

The criteria for stopping the Delphi rounds based on consensus or stability should be identified a priori. The alternative plans and method to drop items should be defined if consensus is used as a stopping criterion of Delphi rounds. Stability of the responses is important for statistical stability of the consensus.

EVALUATION OF RECENT DELPHI STUDIES

We used our nine qualitative evaluation points to assess the quality of recent Delphi studies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic search of the literature was conducted from PubMed and MEDLINE databases between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020. We used a combination of keywords, “Delphi technique” OR “Delphi study” OR “Delphi” AND “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”. We excluded search results that have non-human study subjects, non-English literature, and alternative medicine.

Included studies

Fifty-two Delphi studies were assessed as per the inclusion criteria, and 34 (67.3%) studies[24-57], were finally analyzed using nine evaluation points (Table 1). The data on medical specialty, geographical location, the purpose of the study, conclusion format, number of experts, and Delphi rounds were collected for each study (Table 2). The study methods were scrutinized using nine qualitative evaluation points on a 3-point scale, “yes”, “no”, and “not clear” (Table 2).

Table 1.

Evaluation of Delphi studies on coronavirus disease 2019 that were published in 2020 on nine qualitative evaluation points

|

No.

|

Ref.

|

Medicine field

|

Geographical location (Country/Continent)

|

Aim or purpose

|

Guidance format

|

| 1 | Vitacca et al[24] | Rehabilitation | Italy, Europe | Consensus on pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COVID-19 after discharge from acute care. | Recommendations from experts’ panel. |

| 2 | Mikuls et al[25] | Rheumatology | USA, North America | Guidance to rheumatology providers on the management of adult rheumatic diseases during COVID-19 pandemic. | 77 initial guidance statements converted to 25 final guidance statements. |

| 3 | Greenhalgh et al[26] | Primary health | UK, Europe | To develop early warning score for patients with suspected COVID-19 who need escalation to next level of care. | Development of software for early warning score in COVID-19 patients. |

| 4 | Lamb et al[27] | Respiratory medicine and critical care medicine | USA, NA | Guidance to physicians on the preparation, timing, and technique of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. | Eight recommendations. |

| 5 | Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative[28] | General surgery | Global | Identify the needs of the global OR workforce during COVID-19. | Statements, predominantly standardization of OR pathways, OR staffing, and preoperative screening or diagnosis. |

| 6 | Eibensteiner et al[29] | Nephrology | Europe | To gather expert knowledge and experience to guide the care of children with chronic kidney disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Qualitative expert statements and answers. |

| 7 | Bhandari et al[30] | Gastroenterology | Global | Guidance on how to resume endoscopy services during COVID-19. | Best practice recommendations to aid the safe resumption of endoscopy services globally in the era of COVID-19. |

| 8 | Guckenberger et al[31] | Radiotherapy | NA and Europe | To develop practice recommendations pertaining to safe radiotherapy for lung cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic. | Consensus recommendations in common clinical scenarios of radiotherapy for lung cancer. |

| 9 | Aj et al[32] | General surgery | NA, Europe and Australia | Validation of international COVID-19 surgical guidance during COVID-19 pandemic. | Area of consensus and contentious areas from previous guidelines. |

| 10 | Gelfand et al[33] | Dermatology | NA | Guidance on the management of psoriatic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 22 guidance statements. |

| 11 | Allan et al[34] | Surgery | Global | Guidance on surgery and OR practices during COVID-19 pandemic. | Development of research priorities in discipline of surgery related to COVID-19. |

| 12 | Shanbehzadeh et al[35] | Medical informatics and public health | Iran, Middle east | Development of minimum data set for COVID-19 surveillance system. | Conceptual COVID-19 surveillance model. |

| 13 | Bergman et al[36] | Long-term nursing care | NA | Consensus guidance statements focusing on essential family caregivers and visitors in nursing homes during COVID-19 pandemic. | Recommendations for visitors in long term nursing homes. |

| 14 | Daigle et al[37] | Ophthalmology | Canada | Risk stratifying for oculofacial plastic and orbital surgeries in context of transmission of SARS-CoV-2. | Risk based algorithm for oculoplastic surgeries and recommendations for appropriate PPE. |

| 15 | Sorbello et al[38] | Anaesthesia | Europe | Review of available evidence and scientific publications about barrier-enclosure systems for airway management in suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patients. | Recommendation on enclosure barrier systems. |

| 16 | Jheon et al[39] | Cardiovascular and thoracic surgery | Asia | Thoracic cancer surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. | Recommendations on timing, approach, type of surgery, and postoperative requirements. |

| 17 | Olmos-Gómez et al[40] | Behavioural sciences | Spain, Europe | To know the impact of learning environments and psychological factors. | Future research priorities. |

| 18 | Sawhney et al[41] | Gastroenterology | Global | Study to emphasize patient-important outcomes while considering procedural timing. | Recommendations on procedural timing for common indications for advanced endoscopy during COVID-19. |

| 19 | Sciubba et al[42] | Neurosurgery | USA | Study to device scoring system to help with triaging surgical patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Scoring system to triage spinal surgery cases during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 20 | Errett et al[43] | Environmental health science | USA | Study to develop an Environmental Health Sciences COVID-19 research agenda. | To validate, find limitations, and identify future research priorities. |

| 21 | Arezzo et al[44] | Minimal access surgery | Global | To study and provide recommendations for recovery plan in minimally invasive surgery amid COVID-19 pandemic. | Framework for resumption of surgery with focus on minimally invasive surgeries following COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 22 | Dashash et al[45] | Healthcare education | Syria | To identify essential competencies required for approaching patients with COVID-19. | Core competency points for health care professionals to prepare them for COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 23 | Ramalho et al[46] | Psychiatry | Global | To create a practical and clinically useful protocol for mental health care to be applied in the pandemic. | Consensus protocol for use of telemedicine in psychiatry consults during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 24 | Saldarriaga Rivera et al[47] | Rheumatology | Columbia, SA | To produce recommendations for patients with rheumatological diseases receiving immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies. | Recommendations for pharmacological management of patients with rheumatic diseases during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 25 | Tchouaket Nguemeleu et al[48] | Public health | Canada, NA | Study for development and validation of a time and motion guide to assess the costs of prevention and control interventions for nosocomial infections. | Development and validation of a new instrument for systematic assessment of costs relating to the human and material resources used in nosocomial infection prevention and control. |

| 26 | Santana et al[49] | Nursing | Brazil, SA | To develop an adaptable acceptable nursing protocol during the pandemic. | Protocol for nurse managers to cope with pandemic. |

| 27 | Tang et al[50] | Oncology | China | To develop a risk model based on the experience of recently resumed activities in many cancer hospitals in China to reduce nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2. | Risk model development on the basis of experience from recently resumed cancer hospital. |

| 28 | Jiménez-Rodríguez et al[51] | Public health | Spain | Develop recommendations for telemedicine in video consultations during COVID-19. | Consensus recommendations for healthcare professionals for proper management of video consultation. |

| 29 | Reina Ortiz et al[52] | Public health | Ecuador | Development of bio-safety measures to reduce cross-transmission of SARS-CoV-2. | Biosafety-at-home flyer for high-risk group and health care workers to reduce the risk of cross-transmission. |

| 30 | Douillet et al[53] | Internal medicine | France and Belgium | Identify reliable criteria for hospitalization or outpatient management in mild cases of COVID-19. | Development of toolkit “HOME-CoV rule”, a decision-making support mechanism for clinicians to target patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 requiring hospitalization. |

| 31 | Richez et al[54] | Rheumatology | France | Management of anti-inflammatory agents and disease-modifying-anti-rheumatic-drugs for rheumatological patients during COVID-19. | Recommendations to rheumatologists on management. |

| 32 | Yalçınkaya et al[55] | Physiotherapy and rehabilitation medicine | Turkey | Recommendations for the management of spasticity in Cerebral palsy children during COVID-19 pandemic. | Consensus recommendations for spasticity management in cerebral palsy children. |

| 33 | Tanasijevic et al[56] | Haemato-oncology | USA | To identify minimum hemoglobin for safe transfusion in myelodysplastic syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic. | Recommendations for lowest value of hemoglobin for which transfusions can safely forgo. |

| 34 | Alarcón et al[57] | Dentistry | Latin America | Education and practice in implant Dentistry during COVID-19 pandemic. | Consensus recommendations. |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; OR: Operating room.

Table 2.

Basic information of the Delphi studies included for evaluation

|

No.

|

Ref.

|

Identification of problem area

|

Selection of panel members

|

Anonymity of panellist

|

Controlled feedback

|

Iterative rounds

|

Consensus Criteria

|

Analysis of consensus

|

Closing criteria

|

Group stability

|

Number of rounds

|

Number of experts

|

| 1 | Vitacca et al[24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 20 |

| 2 | Mikuls et al [25] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 14 |

| 3 | Greenhalgh et al[26] | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | No | 4 | 72 |

| 4 | Lamb et al[27] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 13 |

| 5 | Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative[28] | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 339 |

| 6 | Eibensteiner et al[29] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | 4 | 13 |

| z | Bhandari et al[30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 34 |

| 8 | Guckenberger et al[31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 32 |

| 9 | Aj et al[32] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 339 |

| 10 | Gelfand et al[33] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 18 |

| 11 | Allan et al[34] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3 | 213 |

| 12 | Shanbehzadeh et al[35] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 40 |

| 13 | Bergman et al[36] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 21 |

| 14 | Daigle et al[37] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 18 |

| 15 | Sorbello et al[38] | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | - | 0 |

| 16 | Jheon et al[39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 26 |

| 17 | Olmos-Gómez et al[40] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 | 441 |

| 18 | Sawhney et al[41] | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not clear | 3 | 14 |

| 19 | Sciubba et al[42] | Not clear | Not clear | No | Not clear | Yes | No | Yes | No | Not clear | 3 | 16 |

| 20 | Errett et al[43] | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 28 |

| 21 | Arezzo et al[44] | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | 55 |

| 22 | Dashash et al[45] | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3 | 20 |

| 23 | Ramalho et al[46] | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | No | 2 | 16 |

| 24 | Saldarriaga Rivera et al[47] | Yes | No | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | No | 3 | 11 |

| 25 | Tchouaket Nguemeleu et al[48] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | 18 |

| 26 | Santana et al[49] | No | Not clear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not clear | 4 | 6 |

| 27 | Tang et al[50] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | No | Not clear | No | No | No | No | 1 | 83 |

| 28 | Jiménez-Rodríguez et al[51] | No | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 16 |

| 29 | Reina Ortiz et al[52] | No | Yes | Not clear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Not clear | No | 2 | 12 |

| 30 | Douillet et al[53] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | 4 | 51 |

| 31 | Richez et al[54] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Not clear | No | 2 | 10 |

| 32 | Yılmaz Yalçınkaya et al[55] | Yes | Yes | Not clear | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 1 | 60 |

| 33 | Tanasijevic et al[56] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 13 |

| 34 | Alarcón et al[57] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 197 |

Summary of Delphi studies assessment

COVID-19 is a new disease coined by World Health Organization in February 2020. The exponential growth of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted public health, healthcare, and the global economy in an unprecedented manner. The absence of quality evidence on pathophysiology, infection transmission or control, and management of COVID-19 made researchers deploying Delphi methodology for consensus recommendations in various medicinal fields affected by COVID-19. We used our evaluation points for the quality assessment of Delphi technique in 34 selected studies that met the inclusion criteria. The studies from various fields of medicine were included in this analysis. Most of the studies (60%) were done in Europe or North America. The median of 20 (interquartile range-41) experts participated in two (interquartile range-1) Delphi rounds (Table 1).

No single study met all nine evaluation points for quality assessment (Table 1). The systematic identification of the problem area was explicitly declared in 28 (79.41%) studies. The anonymity of panelist was missing in nine (26.47%) studies and not disclosed clearly in another 13 (38.24%) articles. The confidentiality in the identity of panelists was breached in few studies either for video/audio conference or in the final round to generate consensus on the items[25,27,29]. The consensus based on the percentage of agreement and consensus analysis was mentioned in 27 (79.41%) studies. The assessment for stability of the results or consensus was missing in many of the studies with only two studies mentioning this in their methodology.

This systematic evaluation of Delphi studies in medical fields highlights the variations in the research methodology used. There was no single study that could score in all the nine evaluation points.

STRENGTH AND LIMITATIONS OF THE ASSESSMENT

We assessed our evaluation points in a wide variety of Delphi studies across various medical fields. These evaluation points are a focused qualitative tool set to assess any Delphi study on a 3-point scale. The evaluation points can be used by the readers, journal editors, and reviewers to assess the quality of the Delphi methodology.

The limitations of this assessment are the inclusion of only English language published studies in the medical field. The evaluation points were qualitative and did not assess the reporting method of the results.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the nine evaluation points can rapidly assess the quality of Delphi studies and, thus, the creditability of scientific research presented through them.

CONCLUSION

There are no standard quality parameters to evaluate Delphi methods in healthcare research. The vital elements of Delphi methodology include anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, and statistical stability of consensus. The published studies have used modified Delphi, and details on methods like expert panel, consensus, or closing criteria are not explicit. We suggest tools for readers and researchers for a systematic assessment of the quality of the Delphi studies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Prashant Nasa declared to be on the advisory board of Edwards life sciences. Other authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 12, 2021

First decision: February 14, 2021

Article in press: May 19, 2021

Specialty type: Methodology

Country/Territory of origin: United Arab Emirates

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boos J S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Prashant Nasa, Department of Critical Care Medicine, NMC Specialty Hospital, Dubai 00000, United Arab Emirates. dr.prashantnasa@hotmail.com.

Ravi Jain, Critical Care Medicine, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur 302001, Rajasthan, India.

Deven Juneja, Institute of Critical Care Medicine, Max Super Speciality Hospital, New Delhi 110017, India.

References

- 1.Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications, 1975. Available from: https://web.njit.edu/~turoff/pubs/delphibook/ch1.html .

- 2.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Manag Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman CM. The Delphi technique: a critique. J Adv Nurs. 1987;12:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath BA, Brenner MJ, Warrillow SJ, Pandian V, Arora A, Cameron TS, Añon JM, Hernández Martínez G, Truog RD, Block SD, Lui GCY, McDonald C, Rassekh CH, Atkins J, Qiang L, Vergez S, Dulguerov P, Zenk J, Antonelli M, Pelosi P, Walsh BK, Ward E, Shang Y, Gasparini S, Donati A, Singer M, Openshaw PJM, Tolley N, Markel H, Feller-Kopman DJ. Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 era: global and multidisciplinary guidance. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:717–725. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jünger S, Payne S, Brearley S, Ploenes V, Radbruch L. Consensus building in palliative care: a Europe-wide delphi study on common understandings and conceptual differences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, Hobbs M, Henderson E, Wilkins E. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes (Lond) 2019;43:2573–2586. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0313-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han H, Ahn DH, Song J, Hwang TY, Roh S. Development of mental health indicators in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9:311–318. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.4.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Hasselt FM, Oud MJ, Loonen AJ. Practical recommendations for improvement of the physical health care of patients with severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:387–396. doi: 10.1111/acps.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green B, Jones M, Hughes D, Williams A. Applying the Delphi technique in a study of GPs' information requirements. Health Soc Care Community. 1999;7:198–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1999.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robba C, Poole D, Citerio G, Taccone FS, Rasulo FA Consensus on brain ultrasonography in critical care group. Brain Ultrasonography Consensus on Skill Recommendations and Competence Levels Within the Critical Care Setting. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32:502–511. doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences: A Map. Front Public Health. 2020;8:457. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santaguida P, Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, Gilsing A, Griffith LE, Richardson J, Mangin D, Kastner M, Raina P. Protocol for a Delphi consensus exercise to identify a core set of criteria for selecting health related outcome measures (HROM) to be used in primary health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:152. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0831-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn WN. Public policy analysis: an introduction. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell VW. The Delphi technique: an exposition and application. Technol Anal Strateg Manag. 1991;3:333–358. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trevelyan E, Robinson N. Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? Eur J Integr Med . 2015;7:423–428. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant S, Booth M, Khodyakov D. Lack of preregistered analysis plans allows unacceptable data mining for and selective reporting of consensus in Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK. Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 1979;13:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holey EA, Feeley JL, Dixon J, Whittaker VJ. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaffin WW, Talley WK. Individual stability in Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 1980;16:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitacca M, Lazzeri M, Guffanti E, Frigerio P, D'Abrosca F, Gianola S, Carone M, Paneroni M, Ceriana P, Pasqua F, Banfi P, Gigliotti F, Simonelli C, Cirio S, Rossi V, Beccaluva CG, Retucci M, Santambrogio M, Lanza A, Gallo F, Fumagalli A, Mantero M, Castellini G, Calabrese M, Castellana G, Volpato E, Ciriello M, Garofano M, Clini E, Ambrosino N, Arir Associazione Riabilitatori dell'Insufficienza Respiratoria Sip Società Italiana di Pneumologia Aifi Associazione Italiana Fisioterapisti And Sifir Società Italiana di Fisioterapia E Riabilitazione OBOAAIPO. Italian suggestions for pulmonary rehabilitation in COVID-19 patients recovering from acute respiratory failure: results of a Delphi process. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90 doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikuls TR, Johnson SR, Fraenkel L, Arasaratnam RJ, Baden LR, Bermas BL, Chatham W, Cohen S, Costenbader K, Gravallese EM, Kalil AC, Weinblatt ME, Winthrop K, Mudano AS, Turner A, Saag KG. American College of Rheumatology Guidance for the Management of Rheumatic Disease in Adult Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/art.41301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenhalgh T, Thompson P, Weiringa S, Neves AL, Husain L, Dunlop M, Rushforth A, Nunan D, de Lusignan S, Delaney B. What items should be included in an early warning score for remote assessment of suspected COVID-19? BMJ Open. 2020;10:e042626. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamb CR, Desai NR, Angel L, Chaddha U, Sachdeva A, Sethi S, Bencheqroun H, Mehta H, Akulian J, Argento AC, Diaz-Mendoza J, Musani A, Murgu S. Use of Tracheostomy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: American College of Chest Physicians/American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology/Association of Interventional Pulmonology Program Directors Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;158:1499–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative. Surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: operating room suggestions from an international Delphi process. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1450–1458. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eibensteiner F, Ritschl V, Ariceta G, Jankauskiene A, Klaus G, Paglialonga F, Edefonti A, Ranchin B, Schmitt CP, Shroff R, Stefanidis CJ, Walle JV, Verrina E, Vondrak K, Zurowska A, Stamm T, Aufricht C European Pediatric Dialysis Working Group. Rapid response in the COVID-19 pandemic: a Delphi study from the European Pediatric Dialysis Working Group. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:1669–1678. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhandari P, Subramaniam S, Bourke MJ, Alkandari A, Chiu PWY, Brown JF, Keswani RN, Bisschops R, Hassan C, Raju GS, Muthusamy VR, Sethi A, May GR, Albéniz E, Bruno M, Kaminski MF, Alkhatry M, Almadi M, Ibrahim M, Emura F, Moura E, Navarrete C, Wulfson A, Khor C, Ponnudurai R, Inoue H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Kashin S, Nikonov E, Yu H, Maydeo AP, Reddy DN, Wallace MB, Pochapin MB, Rösch T, Sharma P, Repici A. Recovery of endoscopy services in the era of COVID-19: recommendations from an international Delphi consensus. Gut. 2020;69:1915–1924. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guckenberger M, Belka C, Bezjak A, Bradley J, Daly ME, DeRuysscher D, Dziadziuszko R, Faivre-Finn C, Flentje M, Gore E, Higgins KA, Iyengar P, Kavanagh BD, Kumar S, Le Pechoux C, Lievens Y, Lindberg K, McDonald F, Ramella S, Rengan R, Ricardi U, Rimner A, Rodrigues GB, Schild SE, Senan S, Simone CB 2nd, Slotman BJ, Stuschke M, Videtic G, Widder J, Yom SS, Palma D. Practice recommendations for lung cancer radiotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus statement. Radiother Oncol. 2020;146:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aj B, C B, T A, Harper E R, Rl H, Rj E Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative. International surgical guidance for COVID-19: Validation using an international Delphi process - Cross-sectional study. Int J Surg. 2020;79:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, Anesi GL, Blauvelt A, Calabrese C, Dommasch ED, Feldman SR, Gladman D, Kircik L, Lebwohl M, Lo Re V 3rd, Martin G, Merola JF, Scher JU, Schwartzman S, Treat JR, Van Voorhees AS, Ellebrecht CT, Fenner J, Ocon A, Syed MN, Weinstein EJ, Smith J, Gondo G, Heydon S, Koons S, Ritchlin CT. National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force Guidance for Management of Psoriatic Disease During the Pandemic: Version 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1704–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allan M, Mahawar K, Blackwell S, Catena F, Chand M, Dames N, Goel R, Graham YN, Kothari SN, Laidlaw L, Mayol J, Moug S, Petersen RP, Pryor AD, Smart NJ, Taylor M, Toogood GJ, Wexner SD, Zevin B, Wilson MS PRODUCE study. COVID-19 research priorities in surgery (PRODUCE study): A modified Delphi process. Br J Surg. 2020;107:e538–e540. doi: 10.1002/bjs.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanbehzadeh M, Kazemi-Arpanahi H, Mazhab-Jafari K, Haghiri H. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) surveillance system: Development of COVID-19 minimum data set and interoperable reporting framework. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:203. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_456_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergman C, Stall NM, Haimowitz D, Aronson L, Lynn J, Steinberg K, Wasserman M. Recommendations for Welcoming Back Nursing Home Visitors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of a Delphi Panel. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1759–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daigle P, Leung V, Yin V, Kalin-Hajdu E, Nijhawan N. Personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic for oculofacial plastic and orbital surgery. Orbit. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorbello M, Rosenblatt W, Hofmeyr R, Greif R, Urdaneta F. Aerosol boxes and barrier enclosures for airway management in COVID-19 patients: a scoping review and narrative synthesis. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:880–894. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jheon S, Ahmed AD, Fang VW, Jung W, Khan AZ, Lee JM, Sihoe AD, Thongcharoen P, Tsuboi M, Turna A, Nakajima J. Thoracic cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement from the Thoracic Domain of the Asian Society for Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2020;28:322–329. doi: 10.1177/0218492320940162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olmos-Gómez MDC. Sex and Careers of University Students in Educational Practices as Factors of Individual Differences in Learning Environment and Psychological Factors during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawhney MS, Bilal M, Pohl H, Kushnir VM, Khashab MA, Schulman AR, Berzin TM, Chahal P, Muthusamy VR, Varadarajulu S, Banerjee S, Ginsberg GG, Raju GS, Feuerstein JD. Triaging advanced GI endoscopy procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: consensus recommendations using the Delphi method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sciubba DM, Ehresman J, Pennington Z, Lubelski D, Feghali J, Bydon A, Chou D, Elder BD, Elsamadicy AA, Goodwin CR, Goodwin ML, Harrop J, Klineberg EO, Laufer I, Lo SL, Neuman BJ, Passias PG, Protopsaltis T, Shin JH, Theodore N, Witham TF, Benzel EC. Scoring System to Triage Patients for Spine Surgery in the Setting of Limited Resources: Application to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and Beyond. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:e373–e380. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Errett NA, Howarth M, Shoaf K, Couture M, Ramsey S, Rosselli R, Webb S, Bennett A, Miller A. Developing an Environmental Health Sciences COVID-19 Research Agenda: Results from the NIEHS Disaster Research Response (DR2) Work Group's Modified Delphi Method. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arezzo A, Francis N, Mintz Y, Adamina M, Antoniou SA, Bouvy N, Copaescu C, de Manzini N, Di Lorenzo N, Morales-Conde S, Müller-Stich BP, Nickel F, Popa D, Tait D, Thomas C, Nimmo S, Paraskevis D, Pietrabissa A EAES Group of Experts for Recovery Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. EAES Recommendations for Recovery Plan in Minimally Invasive Surgery Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dashash M, Almasri B, Takaleh E, Halawah AA, Sahyouni A. Educational perspective for the identification of essential competencies required for approaching patients with COVID-19. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:1011–1017. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramalho R, Adiukwu F, Gashi Bytyçi D, El Hayek S, Gonzalez-Diaz JM, Larnaout A, Grandinetti P, Nofal M, Pereira-Sanchez V, Pinto da Costa M, Ransing R, Teixeira ALS, Shalbafan M, Soler-Vidal J, Syarif Z, Orsolini L. Telepsychiatry During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Development of a Protocol for Telemental Health Care. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:552450. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.552450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saldarriaga Rivera LM, Fernández Ávila D, Bautista Molano W, Jaramillo Arroyave D, Bautista Ramírez AJ, Díaz Maldonado A, Hernán Izquierdo J, Jáuregui E, Latorre Muñoz MC, Restrepo JP, Segura Charry JS. Recommendations on the management of adult patients with rheumatic diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection. Colombian Association of Rheumatology. Reumatol Clin. 2020;16:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tchouaket Nguemeleu E, Boivin S, Robins S, Sia D, Kilpatrick K, Brousseau S, Dubreuil B, Larouche C, Parisien N. Development and validation of a time and motion guide to assess the costs of prevention and control interventions for nosocomial infections: A Delphi method among experts. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santana RF, Silva MBD, Marcos DADSR, Rosa CDS, Wetzel Junior W, Delvalle R. Nursing recommendations for facing dissemination of COVID-19 in Brazilian Nursing Homes. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73:e20200260. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang Z, Sun B, Xu B. A quick evaluation method of nosocomial infection risk for cancer hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146:1891–1892. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03235-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiménez-Rodríguez D, Ruiz-Salvador D, Rodríguez Salvador MDM, Pérez-Heredia M, Muñoz Ronda FJ, Arrogante O. Consensus on Criteria for Good Practices in Video Consultation: A Delphi Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reina Ortiz M, Grijalva MJ, Turell MJ, Waters WF, Montalvo AC, Mathias D, Sharma V, Renoy CF, Suits P, Thomas SJ, Leon R. Biosafety at Home: How to Translate Biomedical Laboratory Safety Precautions for Everyday Use in the Context of COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:838–840. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douillet D, Mahieu R, Boiveau V, Vandamme YM, Armand A, Morin F, Savary D, Dubée V, Annweiler C, Roy PM HOME-CoV expert group. Outpatient management or hospitalization of patients with proven or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection: the HOME-CoV rule. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:1525–1531. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richez C, Flipo RM, Berenbaum F, Cantagrel A, Claudepierre P, Debiais F, Dieudé P, Goupille P, Roux C, Schaeverbeke T, Wendling D, Pham T, Thomas T. Managing patients with rheumatic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: The French Society of Rheumatology answers to most frequently asked questions up to May 2020. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yılmaz Yalçınkaya E, Karadağ Saygı E, Özyemişci Taşkıran Ö, Çapan N, Kutlay Ş, Sonel Tur B, El Ö, Ünlü Akyüz E, Tekin S, Ofluoğlu D, Zİnnuroğlu M, Akpınar P, Özekli Mısırlıoğlu T, Hüner B, Nur H, Çağlar S, Sezgin M, Tıkız C, Öneş K, İçağasıoğlu A, Aydın R. Consensus recommendations for botulinum toxin injections in the spasticity management of children with cerebral palsy during COVID-19 outbreak. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51:385–392. doi: 10.3906/sag-2009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanasijevic AM, Revette A, Klepin HD, Zeidan A, Townsley D, DiNardo CD, Sebert M, DeZern AE, Stone RM, Magnavita ES, Chen R, Sekeres MA, Abel GA. Consensus minimum hemoglobin level above which patients with myelodysplastic syndromes can safely forgo transfusions. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61:2900–2904. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1791854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alarcón MA, Sanz-Sánchez I, Shibli JA, Treviño Santos A, Caram S, Lanis A, Jiménez P, Dueñas R, Torres R, Alvarado J, Avendaño A, Galindo R, Umanzor V, Shedden M, Invernizzi C, Yibrin C, Collins J, León R, Contreras L, Bueno L, López-Pacheco A, Málaga-Figueroa L, Sanz M. Delphi Project on the trends in Implant Dentistry in the COVID-19 era: Perspectives from Latin America. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2021;32:521–537. doi: 10.1111/clr.13723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]