Abstract

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and have been regarded as benign lesions with little malignant potential, except in the setting of familial adenomatous polyposis. However, in recent years, the prevalence of FGPs has been increasing along with the widespread and frequent use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). To date, several cases of FGPs with dysplasia or carcinoma (FGPD/CAs) have been reported. In this review, we evaluated the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sporadic FGPD/CAs. Majority of the patients with sporadic FGPD/CAs were middle-aged women receiving PPI therapy and without Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Majority of the sporadic FGPD/ CAs occurred in the body of the stomach and were sessile and small with a mean size of 5.4 mm. The sporadic FGPs with carcinoma showed redness, irregular surface structure, depression, or erosion during white light observation and irregular microvessels on the lesion surface during magnifying narrow-band imaging. In addition, sporadic FGPs, even with dysplasia, are likely to progress to cancer slowly. Therefore, frequent endoscopy is not required for patients with sporadic FGPs. However, histopathological evaluation is necessary if endoscopic findings different from ordinary FGPs are observed, regardless of their size. In the future, the prevalence of FGPs is expected to further increase along with the widespread and frequent use of PPIs and decreasing infection rate of H. pylori. Currently, it is unclear whether FGPD/CAs will also increase in the same way as FGPs. However, the trends of these lesions warrant further attention in the future.

Keywords: Sporadic, Fundic gland polyp, Dysplasia, Carcinoma, Proton pump inhibitor, Helicobacter pylori

Core Tip: Majority of the patients harboring sporadic fundic gland polyps with dysplasia or carcinoma were middle-aged women receiving proton pump inhibitor therapy who did not have Helicobacter pylori infection. Majority of the sporadic fundic gland polyps with dysplasia or carcinoma occurred in the body of the stomach and were sessile and small with a mean size of 5.4 mm. The sporadic fundic gland polyps with carcinoma showed redness, irregular surface structure, depression, or erosion during white light observation and irregular microvessels on the lesion surface during magnifying narrow-band imaging.

INTRODUCTION

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps[1]. FGPs are divided into two types: a syndromic type that occurs in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients in the form of polyposis and a sporadic type that occurs in non-FAP patients. Coexistence with dysplasia is more common in the former and has been rare in the latter[2-4].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were launched around 1990, and it has since been reported that PPI use increases the number and size of sporadic FGPs[5-8]. With the widespread and frequent use of PPIs in recent years, the prevalence of FGPs has been increasing, and several cases of sporadic FGPs with dysplasia or carcinoma (FGPD/CAs) have been reported. However, the number of reported cases of FGPD/CAs is still small, and their characteristic features have not yet been fully clarified. Therefore, this review mainly aims to evaluate the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sporadic FGPD/CAs.

PREVALENCE OF FGP WITH OR WITHOUT DYSPLASIA

In the 1990s, FGPs were reported to be prevalent in 0.21%-2.0% of patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy[9-11]. However, since the launch of PPIs around 1990, an increase in the number and size of FGPs associated with PPI use has been reported, and reports since 2000 have shown an obvious increase in the prevalence of FGPs at 5.9%-30.3%[12,13]. FGPs have been reported to occur in 13.6%-36% of patients receiving PPI therapy[5,14]. Carmack et al[1] compared the prevalence of various polyps in the United States population over a one-year period from April 2007 to March 2008 with that in previous reports and noted an increase in FGP prevalence with PPI use. In addition, FGPs can occur in Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-negative stomachs[1,12,13]. In the future, considering that the H. pylori infection rate has been decreasing in recent years[15,16], the prevalence of FGPs is expected to further increase along with the widespread and frequent use of PPIs.

Furthermore, dysplasia has been reported to occur in 25%-54% of syndromic FGPs and 1%-6% of sporadic FGPs, showing a significant difference between FAP and non-FAP patients[2-4]. Given the rarity of FAP patients, FGPD/CAs are less likely to be encountered in daily practice. However, as mentioned above, the prevalence of FGPs is expected to further increase in the future, and the prevalence of FGPD/CAs may increase accordingly. Therefore, it will be necessary to pay attention to the trends of these lesions.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF SPORADIC FGP WITH OR WITHOUT DYSPLASIA/CARCINOMA

Syndromic FGPs associated with FAP patients are common among young people in their 20s, 30s and 40s and do not exhibit gender differences[17-20]. Conversely, sporadic FGPs in non-FAP patients are common among middle-aged women in their 50s and 60s[18,21,22]. Sipponen et al[22] have reported that hormonal levels and imbalance during menopause may play a pathogenetic role in the predominance of women presenting with sporadic FGPs. However, considering that PPI use can cause the development of FGPs in a medicine-related manner[5-7,14], the distribution of age and gender may change in the future owing to the widespread and frequent use of PPIs.

Sporadic FGPs are negatively correlated with H. pylori infection. They are ordinarily observed in the H. pylori-uninfected stomachs without mucosal atrophy and occasionally in the post-eradication setting[1,12,13,23]. In addition, sporadic FGPs exhibit a positive correlation with PPI use; long-term PPI use has been reported to increase the number and size of FGPs[5-8]. However, this change is reversible, and reducing or discontinuing PPI or switching to H2-receptor antagonists has been reported to reduce the increased number and size of FGPs[13,24,25].

The clinical characteristics of sporadic FGPD/CA cases reported so far are shown in Table 1[26-36]. The majority of the patients with FGPD/CAs were middle-aged women (65.7%) with a mean age of 56.7 years, most of whom were receiving PPI therapy and were negative for H. pylori infection. All these characteristics were similar to those of FGPs without dysplasia, and no clinical characteristics different from those of ordinary FGPs were obtained, which implies that it is difficult to discern FGPD/CAs based on the clinical characteristics alone and that H. pylori infection is not likely to be involved in the malignant transformation of FGPs. In addition, Lloyd et al[32] and Arnason et al[37] have reported that the proportion of the patients with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, alcohol use, or smoking among the patients with sporadic FGPDs was low (20%-36%), suggesting that these factors are also not likely to be involved in the malignant transformation of FGPs.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of sporadic fundic gland polyps with dysplasia or carcinoma

|

Ref.

|

Age in yr

|

Gender, M/F

|

Location

|

Size in mm

|

Macroscopictype

|

Endoscopic finding (white light)

|

Pathology

|

PPIuse

|

H. pylori

infection

|

| Jalving et al[26], 2003 | 68 | M | Body fundus | ND | ND | ND | Dysplasia (high grade) | Yes | Negative |

| Kawase et al[27], 2009 | 36 | F | Body | 10 | Sessile | Irregular depression on the top | Carcinoma (intramucosal) | ND | Positive |

| Tazaki et al [28], 2011 | 28 | F | Upper body (posterior wall) | 5 | Sessile | Isochromatic/Smooth surface | Dysplasia (adenoma) | No | Negative |

| 60 | F | Upper body (greater curvature) | 5 | Sessile | Isochromatic/Smooth surface | Dysplasia (adenoma) | No | Negative | |

| 39 | F | Upper body (greater curvature) | 8 | Semi-pedunculated | Partially discolored/Smooth surface | Dysplasia (adenoma) | No | Negative | |

| Jeong et al [29], 2014 | 49 | F | Middle body (anterior wall) | 8 | Pedunculated | Reddish/Erosive surface | Carcinoma (intramucosal) | No | Negative |

| Levy et al [30], 2015 | 56 (median) | M: 29; F: 33 | ND | 5 (mean) | ND | ND | Dysplasia (low grade) | Yes: 49; No: 3; ND: 10 | Negative |

| Togo et al [31], 2016 | 68 | M | Upper body (anterior wall) | 5 | Sessile | Reddish | Carcinoma (intramucosal) | No | Negative |

| 63 | F | Upper body (anterior wall) | 3 | Sessile | Reddish | Carcinoma (intramucosal) | No | Negative | |

| Lloyd et al[32], 2017 | 53 (mean) | M: 5; F: 20 | Body: 14; Fundus: 11; Cardia: 1; ND: 4 | < 5: 13; 5-10: 10; > 10: 1; ND: 1 | Sessile: 20; Pedunculated: 2; ND: 3 | ND | Dysplasia (low grade) | Yes: 17; No: 1; ND: 7 | ND |

| Fukudaet al[33], 2018 | 55 | F | Middle body (greater curvature) | 10 | Sessile | Distorted surface structure | Dysplasia (low grade); Carcinoma (intramucosal) | Yes | Negative |

| Straub et al[34], 2018 | 61 (median) | M: 11; F: 28 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Dysplasia (low grade/high grade) | Yes: 32; No/ND: 7 | Positive: 1; Negative/ND: 38 |

| Shibukawa et al[35], 2019 | 51 | F | Middle body (greater curvature) | 10 | Pedunculated | ND | Dysplasia (low grade); Carcinoma (biopsy specimen) | Yes | Negative |

| 10 | Semi-pedunculated | ND | Dysplasia (low grade) | ||||||

| 10 | Semi-pedunculated | ND | Dysplasia (low grade) | ||||||

| Nawataet al[36], 2020 | 70 | F | Body (greater curvature) | 15 | Sessile | Reddish | Carcinoma (intramucosal) | Yes | Negative |

F: Female; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; M: Male; ND: No data; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor.

Attard et al[3] have reported that dysplasia within FGPs was more common in FAP patients on long-term PPI therapy than in those without PPI therapy. Fukuda et al[33] have stated that PPI therapy may affect the progression of dysplasia within FGPs through their research on the PPI-treated patient harboring FGPD/CA with long-term follow-up. Currently, it remains unclear whether PPI therapy is involved in the malignant transformation of FGPs. However, considering that the development of FGPs in association with PPI therapy is reversible, reducing or discontinuing PPIs or switching to H2-receptor antagonists is recommended for carcinogenesis prevention, at least in cases with multiple FGPs.

ENDOSCOPIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SPORADIC FGP WITH OR WITHOUT DYSPLASIA/CARCINOMA

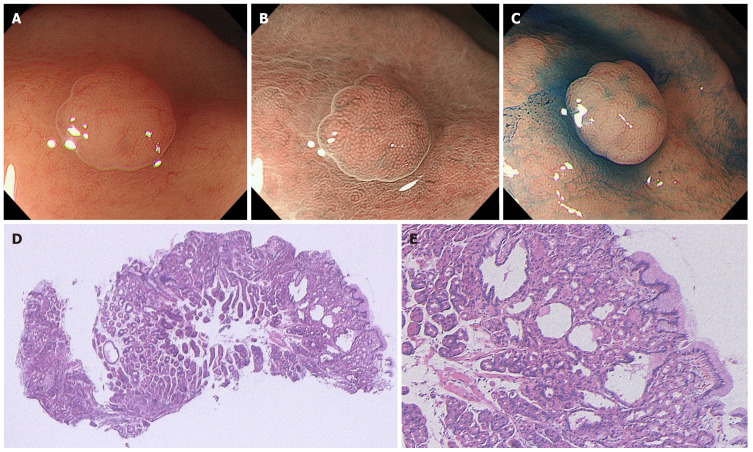

Sporadic FGPs without dysplasia ordinarily occur in the body or fundus of the H. pylori-uninfected stomachs without mucosal atrophy. The polyps are often small (≤ 5 mm) and exhibit a smooth lesion surface structure. During white light observation, they are often recognized as isochromatic sessile polyps, and regular arrangements of collecting venules[38] are observed on the lesion surface as well as on the surrounding non-atrophic mucosa (Figure 1A). During magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI), regularly arranged, white, dot-shaped crypt openings resembling surrounding mucosa are observed (Figure 1B). During chromoendoscopic observation using indigo carmine dye, lesion margins and smooth surface structures are more clearly recognized (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

A case of sporadic fundic gland polyp without dysplasia. A: White light endoscopic view. A 47-year-old man with a complaint of heartburn underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy. He had no medical history of receiving long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and no family history of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). White light endoscopy identified several fundic gland polyp-like lesions in the body of the stomach without atrophic mucosa, suggesting a Helicobacter pylori-uninfected setting. Among them, a 3 mm isochromatic sessile polyp with a smooth surface structure was detected in the middle body; B: Magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) endoscopic view. Magnifying NBI endoscopy revealed regularly arranged, white, dot-shaped crypt openings resembling surrounding mucosa; C: Chromoendoscopic view. Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye revealed less irregularity of the lesion surface. This lesion was endoscopically diagnosed as a fundic gland polyp without dysplasia and was biopsied; D and E: Histopathological view. The histopathological examination revealed a non-dysplastic fundic gland polyp with hyperplastic proliferation of the oxyntic glands and several cystically dilated glands. Colonoscopy did not reveal indications for FAP.

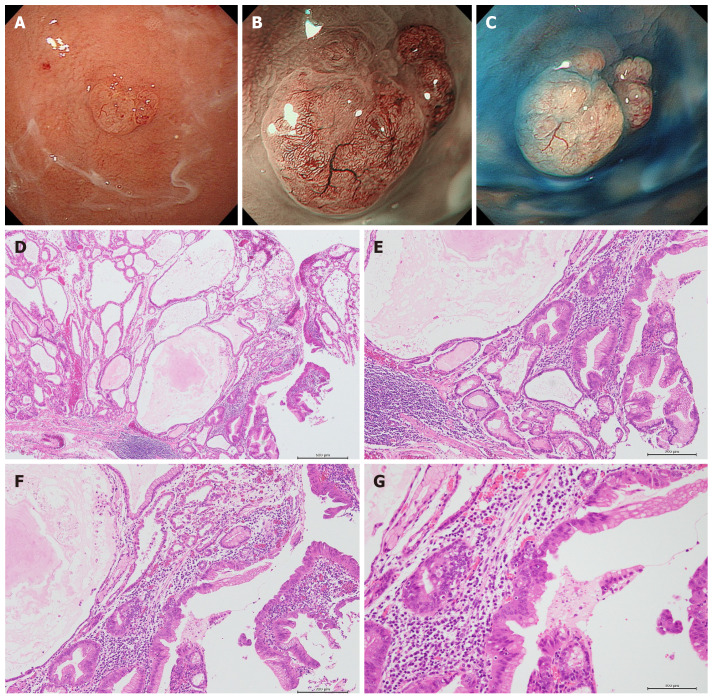

The endoscopic characteristics of sporadic FGPD/CA cases are shown in Table 1[26-36]. Majority of the FGPD/CAs occurred in the body of the stomach and were sessile and small with a mean size of 5.4 mm. Of these, all seven FGPs with carcinoma (FGPCAs) were in the body of the stomach and were slightly larger with a mean size of 8.7 mm, although one of them was diminutive (3 mm). During white light observation, some FGPDs (without carcinoma) were isochromatic lesions with smooth surfaces and were thus difficult to distinguish from ordinary FGPs without dysplasia. However, all the FGPCAs exhibited characteristics unobserved in ordinary FGPs, such as redness, irregular surface structure, depression, and erosion. In addition, irregular microvessels were observed on the lesion surface of all four FGPCAs on which magnifying NBI observation was performed. It has been reported that redness during white light observation and presence of irregular microvessels during magnifying NBI are useful for diagnosing gastric cancer[39-41]. This suggests that similar findings may be useful for diagnosing FGPCAs. Therefore, FGPDs (without carcinoma) may be difficult to distinguish from ordinary FGPs, whereas FGPCAs may be diagnosable by white light or magnifying NBI. One of our cases of FGPCA is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A case of sporadic fundic gland polyp with carcinoma. A: White light endoscopic view. A 73-year-old woman with a complaint of upper abdominal discomfort underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy. She had received long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. White light endoscopy identified several fundic gland polyp-like lesions in the body and fundus of the stomach without atrophic mucosa, suggesting a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-uninfected setting. Among them, a 6 mm isochromatic sessile polyp with a slightly irregular surface structure was detected in the fundus; B: Magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) endoscopic view. Magnifying NBI endoscopy revealed irregular microvessels on the lesion surface; C: Chromoendoscopic view. Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye more clearly revealed the irregularity of the lesion surface. This lesion was endoscopically diagnosed as a fundic gland polyp with dysplasia or carcinoma and was removed by the endoscopic mucosal resection technique; D: Histopathological view (low magnification). The histopathological examination revealed a fundic gland polyp with prominent dilated cystic glands often observed in patients receiving PPI therapy; E-G: Histopathological view (higher magnification of D). This lesion coexisted with epithelial dysplasia and intramucosal well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Serological examination confirmed that she was negative for H. pylori infection. Colonoscopy as well as her family history showed no familial adenomatous polyposis.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL, GENETIC, AND MOLECULAR FINDINGS OF FGP WITH OR WITHOUT DYSPLASIA

FGPs are histopathologically characterized by hyperplastic proliferation of oxyntic glands with distorted glandular architecture and cystically dilated glands (Figure 1D and E)[18]. Epithelial dysplasia is common in syndromic FGPs but rare in sporadic FGPs[2-4]. Long-term PPI use is known to increase the size of FGPs via fundic gland cyst enlargement due to foveolar cell proliferation and parietal cell protrusion[8]. Fukuda et al[8] have reported that in addition to the obstruction of isthmus glands by parietal cell protrusion, a large amount of mucinous product from proliferating foveolar cells in the deeper layer of fundic glands (which is promoted by PPI-induced hypergastrinemia due to decreased acid secretion and related factors) might enlarge fundic gland cysts and result in FGP enlargement.

Abraham et al[42,43] have reported that adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene alteration is more frequent in syndromic FGPs (47%) but less frequent in sporadic FGPs (8%), whereas β-catenin gene alteration is more frequent in sporadic FGPs (91%) but absent in syndromic FGPs. Although APC and β-catenin are both constituent genes of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, these differences in genetic background may explain, in part, why syndromic FGPs exhibit more dysplasia, whereas sporadic FGPs exhibit less dysplasia[43]. In fact, Abraham et al[44] have reported that sporadic FGPDs harbored APC gene alteration (53.8%) rather than β-catenin gene alteration (15.4%), which indicates that sporadic FGPDs are molecularly similar to syndromic FGPs.

Moreover, Hassan et al[45] genetically evaluated syndromic and sporadic FGPs, including dysplastic lesions, and demonstrated no differences in protein expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1 (which are regulated by the APC/β-catenin signaling pathway) between both types of FGPs, despite their different genetic abnormalities. These lesions exhibited no aberrant nuclear localization of β-catenin and exhibited negative nuclear expression of p53 protein and positive nuclear expression of retinoblastoma protein. Additionally, Levy and Bhattacharya[30] and Straub et al[34] have reported that even FGPDs harbored less aberrant nuclear localization of β-catenin and no alteration of p53 gene in both syndromic and sporadic settings. These findings may explain, in part, why both syndromic and sporadic FGPs are less likely to become cancerous, even when exhibiting dysplasia.

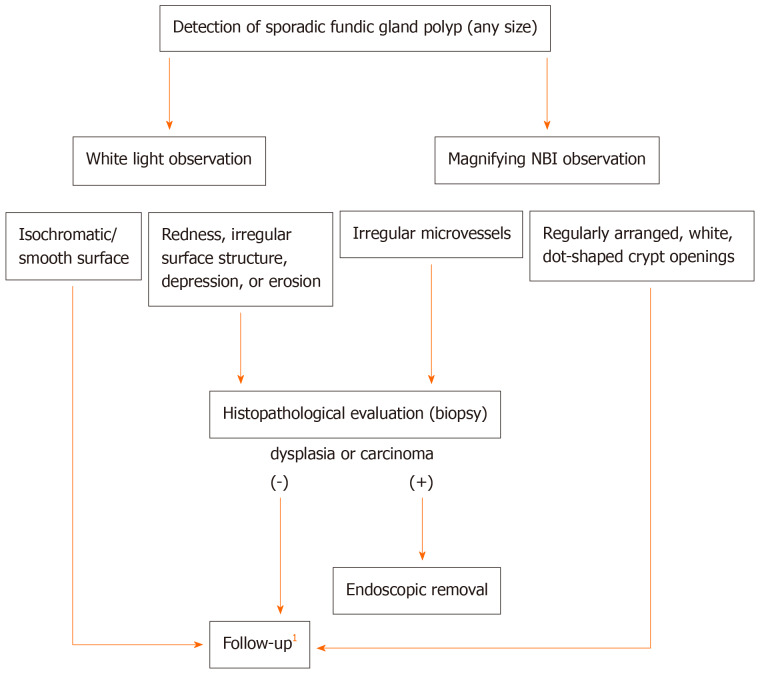

PROPOSAL OF A MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM FOR SPORADIC FGPS

Although FGPs are the most common gastric polyps[1], they are rarely associated with dysplasia or carcinoma in non-FAP patients[2,4]. Additionally, even if sporadic FGPs are accompanied by dysplasia, they are likely to only slowly progress to cancer[30,32,33,37]. Therefore, we believe that it is not always necessary to identify FGPDs at the early stage, and that it would be sufficient if FGPCAs could be removed without being overlooked. A summary of the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sporadic FGPs with or without dysplasia/carcinoma and our proposed management algorithm for sporadic FGPs are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, respectively. The procedure is as follows: (1) When a sporadic FGP is detected, regardless of its size, perform white light observation and, if possible, additional magnifying NBI; (2) During white light observation, pay attention to the presence of redness, irregular surface structure, depression, or erosion in the lesions; (3) During magnifying NBI observation, pay attention to the presence of irregular microvessels on the lesion surface; (4) If none of the above findings are present, a follow-up is acceptable; however, if any of them are present, perform histological evaluation with biopsy; (5) If no findings of dysplasia or carcinoma are identified through biopsy, a follow-up is acceptable; however, if either of them is identified, remove it endoscopically; and (6) If multiple FGPs (e.g., ≥ 20) are detected in patients receiving PPI therapy, consider reducing or discontinuing PPI or switching to H2-receptor antagonists. We believe that the above procedure can detect and remove FGPCAs with high sensitivity. Moreover, considering that some FGPDs may be difficult to distinguish from ordinary FGPs and that Lloyd et al[32] have reported that no gastric cancer occurred during the average follow-up period of 4.4 years for sporadic FGPDs, the appropriate endoscopy intervals should be set to every 3-5 years in both the non-removal follow-up and post-removal surveillance groups. However, a shorter endoscopy interval is necessary for the H. pylori-eradicated patients with sporadic FGP because of the higher risk of developing conventional gastric cancer, which does not originate from an FGP, in the atrophic mucosa[46].

Table 2.

Summary of the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sporadic fundic gland polyps with or without dysplasia/carcinoma

|

|

Fundic gland polyps (without dysplasia)

|

Fundic gland polyps with dysplasia

|

Fundic gland polyps with carcinoma

|

| Age in yr [range] | 50-60 s | 56.71[24-88] | |

| 56.71[24-88] | 56.01[36-70] | ||

| Gender | M < F | M < F | |

| Size in mm [range] | ≤ 5 | 5.41[1-20] | |

| 5.21[1-20] | 8.71[3-15] | ||

| Endoscopic findings (white light) | Isochromatic/smooth surface | Redness, irregular surface structure, depression, or erosion2 | |

| Endoscopic findings (magnifying NBI) | Regularly arranged, white, dot-shaped crypt openings | ND | Irregular microvessels |

Mean values of the cases presented in Table 1.

Some fundic gland polyps with dysplasia are isochromatic lesions with smooth surfaces. F: Female; M: Male; NBI: Narrow-band imaging; ND: No data.

Figure 3.

Proposal of a management algorithm for sporadic fundic gland polyps. 1If multiple fundic gland polyps are detected in patients receiving proton pump inhibitor therapy, reducing or discontinuing proton pump inhibitor therapy or switching to H2-receptor antagonists is recommended. NBI: Narrow-band imaging.

LIMITATIONS

The limitation of this review is the small sample size. Despite including our case that has been presented in this manuscript, the number of sporadic FGPCAs comprised eight lesions, and the magnifying NBI findings of FGPCAs were limited to five lesions. Although the number of cases of sporadic FGPCAs was small, we found common findings among these cases. Therefore, we have proposed a management algorithm for sporadic FGPs based on these limited cases. However, further case reports are needed to evaluate the applicability of this algorithm. We hope that further cases of FGPD/ CAs will be reported, and that this algorithm will be widely used with sufficient applicability, contributing to reduced gastric cancer morbidity and mortality in the future H. pylori-negative era.

CONCLUSION

In this review, we evaluated the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sporadic FGPD/CAs and proposed a management algorithm for sporadic FGPs. In the future, the prevalence of FGPs is expected to further increase along with the widespread and frequent use of PPIs and decreasing infection rate of H. pylori. Currently, it is unclear whether FGPD/CAs will also increase in the same way as FGPs. However, the trends of these lesions warrant further attention in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Takahiro Fujimori for acquiring the histopathological images and for his useful advice regarding histopathological assessment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, No. 032993.

Peer-review started: February 7, 2021

First decision: April 19, 2021

Article in press: June 2, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jamali R, Shahidi N S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

Contributor Information

Wataru Sano, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan. watasano@yahoo.co.jp.

Fumihiro Inoue, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

Daizen Hirata, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

Mineo Iwatate, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

Santa Hattori, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

Mikio Fujita, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

Yasushi Sano, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Kobe 655-0031, Hyogo, Japan.

References

- 1.Carmack SW, Genta RM, Schuler CM, Saboorian MH. The current spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1524–1532. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu TT, Kornacki S, Rashid A, Yardley JH, Hamilton SR. Dysplasia and dysregulation of proliferation in foveolar and surface epithelia of fundic gland polyps from patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:293–298. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attard TM, Yardley JH, Cuffari C. Gastric polyps in pediatrics: an 18-year hospital-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:298–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Boersma-van Ek W, de Jong S, Karrenbeld A, Hollema H, de Vries EG, Kleibeuker JH. Dysplasia in fundic gland polyps is associated with nuclear beta-catenin expression and relatively high cell turnover rates. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:916–922. doi: 10.1080/00365520310005433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, DE Jong S, Kleibeuker JH. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1341–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin FC, Chenevix-Trench G, Yeomans ND. Systematic review with meta-analysis: fundic gland polyps and proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:915–925. doi: 10.1111/apt.13800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran-Duy A, Spaetgens B, Hoes AW, de Wit NJ, Stehouwer CD. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risks of Fundic Gland Polyps and Gastric Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14: 1706-1719. :e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda M, Ishigaki H, Sugimoto M, Mukaisho KI, Matsubara A, Ishida H, Moritani S, Itoh Y, Sugihara H, Andoh A, Ogasawara K, Murakami K, Kushima R. Histological analysis of fundic gland polyps secondary to PPI therapy. Histopathology. 2019;75:537–545. doi: 10.1111/his.13902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita Y, Tojo M, Yano T, Kitajima N, Itoh T, Nishiyama K, Inatome T, Fukuzaki H, Watanabe M, Chiba T. Incidence of fundic gland polyps in patients without familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:161–163. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Declich P, Isimbaldi G, Sironi M, Galli C, Ferrara A, Caruso S, Baldacci MP, Stioui S, Privitera O, Boccazzi G, Federici S. Sporadic fundic gland polyps: an immunohistochemical study of their antigenic profile. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:808–815. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickey W, Kenny BD, McConnell JB. Prevalence of fundic gland polyps in a western European population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:73–75. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199607000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genta RM, Schuler CM, Robiou CI, Lash RH. No association between gastric fundic gland polyps and gastrointestinal neoplasia in a study of over 100,000 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notsu T, Adachi K, Mishiro T, Ishimura N, Ishihara S. Fundic gland polyp prevalence according to Helicobacter pylori infection status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1158–1162. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hongo M, Fujimoto K Gastric Polyps Study Group. Incidence and risk factor of fundic gland polyp and hyperplastic polyp in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy: a prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:618–624. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamada T, Haruma K, Ito M, Inoue K, Manabe N, Matsumoto H, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Akiyama T, Tanaka S, Shiotani A, Graham DY. Time Trends in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis Over 40 Years in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:192–198. doi: 10.1111/hel.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leja M, Grinberga-Derica I, Bilgilier C, Steininger C. Review: Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2019;24 Suppl 1:e12635. doi: 10.1111/hel.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iida M, Yao T, Itoh H, Watanabe H, Kohrogi N, Shigematsu A, Iwashita A, Fujishima M. Natural history of fundic gland polyposis in patients with familial adenomatosis coli/Gardner's syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odze RD, Marcial MA, Antonioli D. Gastric fundic gland polyps: a morphological study including mucin histochemistry, stereometry, and MIB-1 immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:896–903. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, Pennazio M, Tansini P, Arrigoni A, Rossini FP, Ponz de Leon M, Bedogni G. Dysplastic changes in gastric fundic gland polyps of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi LK, Burke CA, Bennett AE, Lopez R, Hasson H, Church JM. Fundic gland polyp dysplasia is common in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcial MA, Villafaña M, Hernandez-Denton J, Colon-Pagan JR. Fundic gland polyps: prevalence and clinicopathologic features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1711–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sipponen P, Laxén F, Seppälä K. Cystic 'hamartomatous' gastric polyps: a disorder of oxyntic glands. Histopathology. 1983;7:729–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okano A, Takakuwa H, Matsubayashi Y. Development of sporadic gastric fundic gland polyp after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Dig Endosc. 2008;20:41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhry U, Boyce HW Jr, Coppola D. Proton pump inhibitor-associated gastric polyps: a retrospective analysis of their frequency, and endoscopic, histologic, and ultrastructural characteristics. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:615–621. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamada K, Takeuchi Y, Akasaka T, Iishi H. Fundic Gland Polyposis Associated with Proton-Pump Inhibitor Use. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000607. doi: 10.12890/2017_000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Götz JM, van der Waaij LA, de Jong S, Zwart N, Karrenbeld A, Kleibeuker JH. High-grade dysplasia in sporadic fundic gland polyps: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1229–1233. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200311000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawase R, Nagata S, Onoyama M, Nakayama N, Honda Y, Kuwahara K, Kimura S, Tsuji K, Ohgoshi H, Sakatani A, Kaneko M, Ito M, Shimamoto F, Hidaka T. A case of gastric adenocarcinoma arising from a fundic gland polyp. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2009;2:279–283. doi: 10.1007/s12328-009-0096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tazaki S, Nozu F, Yosikawa N, Imawari M, Suzuki N, Tominaga K, Hoshino M, Suzuki S, Hayashi K. Sporadic fundic gland polyp-related adenomas occurred in non-atrophic gastric mucosa without helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:182–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong YS, Kim SE, Kwon MJ, Seo JY, Lim H, Park JW, Kang HS, Moon SH, Kim JH, Park CK. Signet-ring cell carcinoma arising from a fundic gland polyp in the stomach. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18044–18047. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.18044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy MD, Bhattacharya B. Sporadic Fundic Gland Polyps With Low-Grade Dysplasia: A Large Case Series Evaluating Pathologic and Immunohistochemical Findings and Clinical Behavior. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:592–600. doi: 10.1309/AJCPGK8QTYPUQJYL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Togo K, Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Honda H, Ishida T, Tanabe H, Yao K, Iwashita A, Murakami K. Two cases of adenocarcinoma occurring in sporadic fundic gland polyps observed by magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9028–9034. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.9028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloyd IE, Kohlmann WK, Gligorich K, Hall A, Lyon E, Downs-Kelly E, Samowitz WS, Bronner MP. A Clinicopathologic Evaluation of Incidental Fundic Gland Polyps With Dysplasia: Implications for Clinical Management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1094–1102. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda M, Ishigaki H, Ban H, Sugimoto M, Tanaka E, Yonemaru J, Kuroe S, Namura T, Matsubara A, Moritani S, Murakami K, Andoh A, Kushima R. No transformation of a fundic gland polyp with dysplasia into invasive carcinoma after 14 years of follow-up in a proton pump inhibitor-treated patient: A case report. Pathol Int. 2018;68:706–711. doi: 10.1111/pin.12739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straub SF, Drage MG, Gonzalez RS. Comparison of dysplastic fundic gland polyps in patients with and without familial adenomatous polyposis. Histopathology. 2018;72:1172–1179. doi: 10.1111/his.13485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibukawa N, Wakahara Y, Ouchi S, Wakamatsu S, Kaneko A. Synchronous Three Gastric Fundic Gland Polyps with Low-grade Dysplasia Treated with Endoscopic Mucosal Resection after Being Diagnosed to Be Tubular Adenocarcinoma Based on a Biopsy Specimen. Intern Med. 2019;58:1871–1875. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2081-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawata Y, Ichihara S, Hirasawa D, Tanaka I, Unno S, Igarashi K, Matsuda T. A case of gastric adenocarcinoma considered to originate from a sporadic fundic gland polyp in a Helicobacter pylori-uninfected stomach. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:740–745. doi: 10.1007/s12328-020-01139-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnason T, Liang WY, Alfaro E, Kelly P, Chung DC, Odze RD, Lauwers GY. Morphology and natural history of familial adenomatous polyposis-associated dysplastic fundic gland polyps. Histopathology. 2014;65:353–362. doi: 10.1111/his.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yagi K, Aruga Y, Nakamura A, Sekine A. Regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC): a characteristic endoscopic feature of Helicobacter pylori-negative normal stomach and its relationship with esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maki S, Yao K, Nagahama T, Beppu T, Hisabe T, Takaki Y, Hirai F, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging is useful in the differential diagnosis between low-grade adenoma and early cancer of superficial elevated gastric lesions. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:140–146. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao K, Anagnostopoulos GK, Ragunath K. Magnifying endoscopy for diagnosing and delineating early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:462–467. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao K. Clinical Application of Magnifying Endoscopy with Narrow-Band Imaging in the Stomach. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:481–490. doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.48.6.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abraham SC, Nobukawa B, Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Wu TT. Fundic gland polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis: neoplasms with frequent somatic adenomatous polyposis coli gene alterations. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:747–754. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64588-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abraham SC, Nobukawa B, Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Wu TT. Sporadic fundic gland polyps: common gastric polyps arising through activating mutations in the beta-catenin gene. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abraham SC, Park SJ, Mugartegui L, Hamilton SR, Wu TT. Sporadic fundic gland polyps with epithelial dysplasia : evidence for preferential targeting for mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassan A, Yerian LM, Kuan SF, Xiao SY, Hart J, Wang HL. Immunohistochemical evaluation of adenomatous polyposis coli, beta-catenin, c-Myc, cyclin D1, p53, and retinoblastoma protein expression in syndromic and sporadic fundic gland polyps. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohba R, Iijima K. Pathogenesis and risk factors for gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:663–672. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i9.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]