Abstract

Although the most common neuro-otolaryngological findings associated with COVID-19 infection are chemosensory changes, it should be known that these patients may present with different clinical findings. We present a 57-year-old woman who developed progressive hoarseness while suffering from COVID-19 infection without a history of chronic disease or any other etiological cause. Laryngeal fiberscopy revealed left vocal cord fixed at the cadaveric position and there was a 5–6-mm intraglottic gap during phonation. No other etiological causes were found in the examinations performed with detailed ear-nose-throat examination, neurological evaluations, and imaging methods. Injection laryngoplasty was applied to the patient, and voice therapy was initiated, resulting in significant improvement in voice quality. The mechanism of the idiopathic vocal cord paralysis remains unclear; it is suspected to be related to COVID-19 neuropathy, because the patient had no pre-existing vascular risk factors or evidence of other neurologic diseases on neuroimaging. Laryngeal nerve palsies may represent part of the neurologic spectrum of COVID-19. When voice changes occur in patients during COVID 19 infection, the possibility of vocal cord paralysis due to peripheral nerve damage caused by the SARS-CoV-2 should be considered.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vocal cord paralysis, Complication, Voice, Recurrent nerve

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the causative agent of which is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The SARS-CoV-2 virus, the last identified member of the coronavirus family, is a single-stranded RNA virus that is transmitted via droplets [1]. It leads to significant morbidity and its mortality rate is estimated to be around 3.4% [2].

With the emergence of the COVID-19 infection, clinicians around the world have highlighted the variation in symptoms of the disease in their reports. While the most common symptoms of the disease are high fever, cough, and shortness of breath, other reported findings include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, sore throat, tiredness, muscle pain, and loss of taste and smell [3]. Although the SARS-CoV-2 virus primarily affects the respiratory tract, its neurotropic effect is demonstrated by experimental studies and case reports. The most prominent characteristic of the COVID-19 virus that distinguishes it from other upper respiratory tract infections is the findings of nerve and neurological involvement through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors [4]. Therefore, different cranial and peripheral nerve involvement findings and case reports associated with COVID-19 infection have been reported [5].

There are sample studies on different viral agents in the etiology of idiopathic vocal cord paralysis (VCP) [6]. The literature review has shown one case report presenting bilateral VCP associated with COVID-19 infection recently [7]. Here, we present other case of sudden unilateral VCP that is thought to be associated with COVID-19 infection.

Case Report

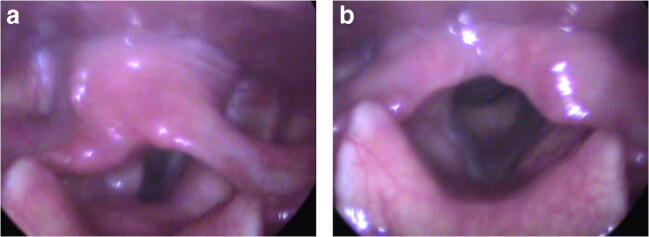

A 57-year-old female patient presented to otolaryngology outpatient clinic with complaint of hoarseness. The patient with no known history of surgery or chronic disease had no recent upper respiratory tract infection, trauma, or surgery history, except for COVID-19 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test fifteen days ago. She stated that she had complaints of myalgia, arthralgia, and severe cough during the disease, which were accompanied by hoarseness that started gradually seven days after the result came out positive. The thorax computed tomography (CT) performed during this period showed no findings compatible with pneumonia. The patient was followed as an outpatient without the need for hospitalization. However, she was admitted to our outpatient clinic since hoarseness continued despite the second COVID-19 test result became negative. The examination revealed paralysis in the cadaveric position of the left vocal cord during phonation and respiration (Fig. 1 A and B). Furthermore, arytenoid was observed to be immobile, suggesting involvement of the superior laryngeal nerve [7]. Contrast-enhanced cranial MRI and thoracic CT scan were performed to exclude other etiologic causes. No cranial, cervical, or thoracic mass or pathology was found that could be an etiologic cause that affects recurrent laryngeal nerve function. Serological laboratory tests (sedimentation, CRP, pro-calcitonin) were performed to exclude increased inflammatory parameters or ongoing neurotropic viral infection (CMV). Laboratory tests did not reveal any findings suggestive of other viral agents or systemic diseases. Contrast-enhanced CT examinations of the brain, chest, and neck did not reveal any etiological cause. Only in neck CT, an appearance supporting VCP was reported. Similarly, neurological examination revealed no signs of other possible cranial/peripheral nerve involvement or additional neurological deficits. Acoustic analysis and voice handicap index (VHI) assessment were performed and VHI score was found to be 40. In the aerodynamic evaluation using the s/z ratio was 1.36, the maximum phonation time was 4.23 seconds with the vowel /a/ and 5.22 seconds with the vowel /i/. In the acoustic analysis performed using Praat© acoustic analysis program, the Jitter, shimmer, and noise-to-harmonic ratio (NHR) were found to be 16.32, 43.38, and 1.86, respectively.

Fig. 1.

A The position of vocal cords during phonation. The left vocal cord is seen to be in the lateral position. B The position of vocal cords during respiration

Voice therapy was initiated and injection laryngoplasty with Radiesse® injection into the left vocal cord was performed under general anesthesia one month later the diagnosis. Significant improvement was observed in voice quality and acoustic parameters in the postoperative period.

Discussion

The most obvious theory of the neurological effects of the COVID-19 virus is the mechanism of ACE2, which is identified as a functional receptor of SARS-CoV-2. The virus reaches host cells via the ACE2 receptor. This enzyme receptor is found mostly in type II alveolar cells in the lungs [4]. It is also produced by many cells, including glial cells and neurons. The presentation and distribution of ACE2 suggests that the COVID-19 virus may cause neurological-neural involvement through direct or indirect mechanisms. Studies have shown that the virus enters the central nervous system through the olfactory nerve, another pathway, and can spread from neuron to neuron via axonal transport [5]. Apart from direct neurological system invasion of the virus, neurological complications associated with COVID-19 may occur as a result of widespread cardiopulmonary insufficiency and metabolic abnormalities induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or mechanisms of autoimmunity [8]. Neurological complications associated with COVID-19 can be divided into two: central and peripheral nervous system complications. While common central nervous system complications include headache, cerebrovascular events, encephalitis, and imbalance, the most common findings of peripheral nervous system complications are anosmia/hyposmia and chemosensory dysfunctions [5]. Furthermore, cases reported in the literature in terms of peripheral nerve involvement associated with COVID-19 virus are Guillain-Barré syndrome, facial nerve palsy, abducens nerve paralysis, optic neuritis, and phrenic nerve involvement [9–12]. In a recent publication, a case of bilateral vocal cord paralysis thought to be associated with COVID-19 was also shared [7].

In this present case, the patient had a complaint of hoarseness that started concurrently with the COVID-19 infection. The examination performed following the COVID-19 positivity revealed left VCP, and there was no other reason to explain this condition in the etiology of the disease. In our case, unlike the other VCP case reported in the literature [7], the clinical status of COVID-19 was milder and the patient did not have a history of intubation. The absence of pneumonia in the thorax CT findings of the patient suggested that it was due to vagal neuritis caused by nerve invasion of the virus, rather than the nerve being affected with possible mediastinal involvement. In addition, unilateral vocal cord paralysis and the absence of additional signs or examination findings of cranial nerve involvement in the patient were significant in terms of mononeuritis clinics that can be seen in COVID-19.

The literature review has shown that varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes zoster virus play a role in the etiology of unilateral or bilateral VCP cases [6]. Although coronaviruses are a diverse family of viruses, they can lead to different symptoms in cases infected with COVID-19 as they are associated with high rates of neurological involvement. Although we do not have objective data to prove definitively this situation, when we consider other possible viral etiologies, the most likely factor that could explain idiopathic VCP in our patient was the COVID-19 virus. Moreover, the present case will be thought-provoking for evaluating the movements of the vocal cords and changes in the voice quality in patients being infected with COVID-19 during the pandemic.

Availability of Data and Material

Yes

Author Contribution

Collecting data: M. Ozcelik Korkmaz; writing and editing: M. Ozcelik Korkmaz, M. Guven.

Declarations

Consent to participate

Yes

Consent for Publication

Yes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;3099:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global research on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-onnovel-coronavirus-2019-ncov. v1; 2020 .10.05.2021.

- 3.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, Ma K, Xu D, Yu H, Wang H, Wang T, Guo W, Chen J, Ding C, Zhang X, Huang J, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;26:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vonck K, Garrez I, De Herdt V, et al. Neurological manifestations and neuro-invasive mechanisms of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1578–1587. doi: 10.1111/ene.14329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt NK, Pipkorn P, Paniello RC. Association between upper respiratory infection and idiopathic unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127:667–671. doi: 10.1177/0003489418787542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jungbauer F, Hülse R, Lu F, Ludwig S, Held V, Rotter N, Schell A. Case report: Bilateral palsy of the vocal cords after COVID-19 infection. Front Neurol. 2021;12:619545. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.619545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orestes MI, Chhetri DK. Superior laryngeal nerve injury: effects, clinical findings, prognosis, and management options. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22(6):439–443. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paliwal KM, Garg RK, Gupta A, Tejan N. Neuromuscular presentations in patients with COVID-19. Neurological Sciences. 2020;41:3039–3056. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Rumeileh S, Abdelhak A, Foschi M, Tumani H, Otto M. Guillain-Barré syndrome spectrum associated with COVID-19: an up-to-date systematic review of 73 cases. J Neurol. 2021;268:1133–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falcone MM, Rong AJ, Salazar H, Redick DW, Falcone S, Cavuoto KM. Cavuoto, MD. Acute abducens nerve palsy in a patient with the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J AAPOS. 2020;24:216–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurier F, Godbert B, Perrin J. Respiratory distress in SARS-CoV-2 without lung damage: phrenic paralysis should be considered in COVID-19 infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;21:7(6). doi: 10.12890/2020_001728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]