Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence over time and predictors of problematic internet use using the Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS). We also identified an intermediate-risk PRIUSS score.

Study design

In this longitudinal cohort study, we recruited participants using random selection from 2 colleges. Participants completed a yearly PRIUSS. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate predictors of problematic internet use. We pursued receiver operating curve analysis to identify an Intermediate risk PRIUSS score. Finally, we applied Markov modeling to test the dynamics of moving through problematic internet use risk states over time.

Results

Of 319 participants, 56% were female, 58% were from the Midwest, and 75% were white. Problematic internet use prevalence estimates varied between 9% and 11% over the 4 years. Problematic internet use risk status from the previous time period was identified as the main predictor for problematic internet use (OR 24.1, 95% CI 12.8-45.4, P < .0001). Receiver operating curve analysis identified the optimal threshold for defining Intermediate risk was a PRIUSS score of 15.

Conclusions

This longitudinal study of problematic internet use among college students found that risks were present across groups and over time. The most salient predictor of problematic internet use was being at risk at the previous time point. On the basis of these results, we propose a PRIUSS score of 15 as an intermediate-risk cut-off to better identify those at risk of developing problematic internet use.

Keywords: adolescents, technology, internet addiction, longitudinal, cohort study, scale development, screening

Problematic internet use, an ongoing health concern among adolescents and young adults, is defined as “Internet use that is risky, excessive or impulsive in nature leading to adverse life consequences, specifically physical, emotional, social or functional impairment.”1 Problematic internet use has been associated with poor academic performance, stress, and fewer positive health behaviors.2 Studies also have suggested bidirectional relationships between problematic internet use and other mental health conditions, such as depression.3, 4, 5

To date, there are no effective or efficacious interventions specific to problematic internet use. Thus, prevention and early identification of those at risk is paramount. To facilitate early identification of those at risk, a validated instrument is necessary. The Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS)6 was developed based on a previous study that developed a conceptual framework for problematic internet use.1 The current PRIUSS cutoff categorizes participants as “at risk” for problematic internet use or “not at risk” based on their overall PRIUSS score.7 To date, there are no criteria within the PRIUSS that identify participants at intermediate risk. Previous studies using the PRIUSS suggest that approximately 7%-11% of college students meet criteria as at risk for problematic internet use.6, 8, 9

The vast majority of studies of problematic internet use to date have been cross-sectional, yielding point prevalence for study samples at single time points. Few studies have evaluated risk factors for problematic internet use, although previous studies have identified correlations between problematic internet use and male sex.10, 11, 12 However, other studies focused on problematic social media use have identified correlations with female sex.13 A critical gap in the literature is longitudinal cohort studies to understand patterns of risk over time for individuals; little is understood about risk factors preceding the development of problematic internet use. Thus, the purpose of this longitudinal cohort study was to evaluate the prevalence estimate and predictors of problematic internet use over time among college students and to identify an intermediate-risk PRIUSS score toward earlier identification of being at risk.

Methods

Data from this study were derived from a larger prospective longitudinal cohort study focused on health and technology. Data used in this study included yearly participant interviews throughout 4 years of college.

Two large state universities were included in this study, one in the Midwest and one in the Northwest. Data for this study were collected yearly between May and June; overall study dates were between May 15, 2012, and June 15, 2015. This study was approved by the institutional review boards from the 2 participating universities.

Subjects

We recruited high school graduates the summer before college who were enrolled at 1 of the 2 participating universities. We randomly selected potential participants from the college registrar's lists of enrolled freshmen students at the 2 universities to recruit. Participants were eligible if they were between the ages of 17 and 19 years and enrolled as a freshman at 1 of these 2 universities. Informed consent was obtained from parents of minors and assent from minor participants, informed consent was obtained from all participants aged 18 and 19 years.

Recruitment

Potentially eligible incoming students were recruited using phone calls, e-mails, or Facebook messages. Sample size and exclusion criteria were established by the larger study; we excluded students who were non-English speaking, had begun college early, or did not have a Facebook profile at the time of enrollment.

Interview Procedure

This study included yearly phone interviews. Baseline interviews were conducted upon study enrollment to obtain demographic data. Trained staff conducted interviews yearly at the conclusion of each year of college. Participants were contacted by e-mail and phone to schedule their yearly interview. Interview data were recorded using a customized secure FileMaker database.

Measures

The PRIUSS was developed in 2011 and is grounded in a published conceptual framework for problematic internet use.14 The PRIUSS is an 18-item risk-based screening scale for problematic internet use with questions organized into 3 subscales: social impairment, emotional impairment, and risky/impulsive internet use. This scale has been validated in English and in Dutch.12 The PRIUSS response options use a Likert scale with scores of 0 through 4. Answers include never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, and very often = 4. In the PRIUSS, a cutoff of 26 is used to identify those at risk of problematic internet use.6 Demographic variables included sex, race/ethnicity, and university attended.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic variables and PRIUSS scores were summarized in terms of frequencies and percentages. All reported P values were 2-sided, and P < .05 was used to define statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software, version 2.15.1 (www.cran.r-project.org). Due to the limited number of non-white participants, the categories for race were collapsed into a binary white or non-white variable during analysis.

Prevalence Estimates of Problematic Internet Use over Time

Prevalence estimates of problematic internet use for each of the 4 years of the study were analyzed and reported along with the corresponding 95% CI. We evaluated differences over time using a logistic regression model with subject-specific random effects to account for repeated measurements.

Predictors of Problematic Internet Use over Time

Multivariate logistic regression analysis with subject-specific random effects was conducted to evaluate meeting criteria for at-risk for problematic internet use. The outcome variable was at risk at a current time point, the at-risk stats from the previous time point was included as a predictor. Additional predictors in the model included study year, sex, race, and university.

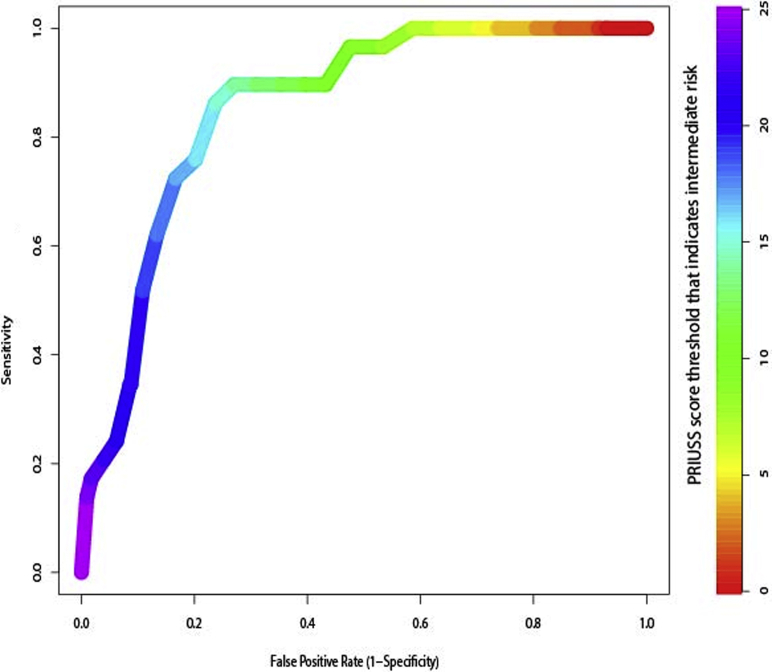

Defining an Intermediate-Risk PRIUSS Score

We also pursued whether having an intermediate-risk PRIUSS score could predict progressing to an at-risk PRIUSS score at future time points. We examined the association between the PRIUSS score from the previous time point and risk of problematic internet use at the current time point to identify an Intermediate risk cutoff. The optimal cut-off was determined by maximizing the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1) of the receiver operating curve.15 Sensitivity and specificity estimates of the intermediate-risk cutoff were reported along with the corresponding 95% CIs.

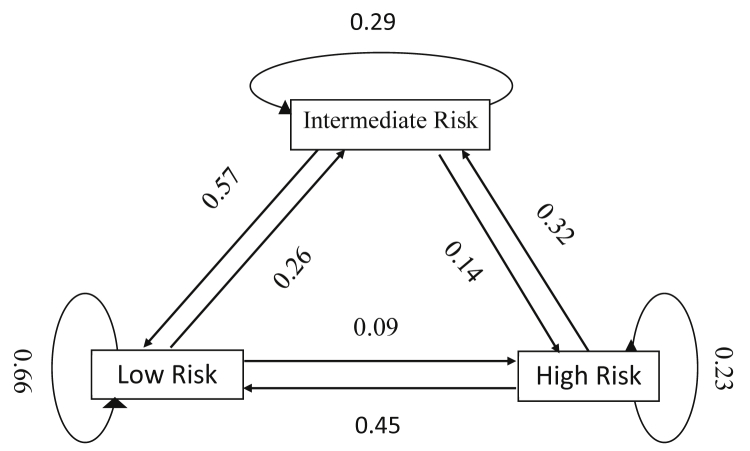

Transitions between Risk States

We used a multistate Markov modeling approach to describe and evaluate the dynamics of moving through the no-at-risk and at-risk problematic internet use states over time.16 This allowed us to test the directionality and progression through at-risk states. We also assessed the Intermediate risk cutoff in these transitions between risk states. The results of the multistage Markov modeling were displayed graphically using a path diagram.

Missing Data

The majority of the participants (75%) completed the PRIUSS questionnaire every year; the completion rates for the 4 years of the study ranged between 81% and 98%. In the primary analysis, observations with missing PRIUSS assessment were excluded from the analysis. To evaluate the effect of missing data on the results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. We compared the results obtained from the primary analysis with the results obtained from imputation-based analyses. Multi-imputation using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method was used to conduct the imputation-based analysis.17 Given there were no differences identified, we present the results without imputation.

Results

In total, 319 participants were included in this study. At the time of enrollment, participant's mean age was 18 years (SD 0.8). Participants were 56% female, 58% from the Midwest campus, and mostly white (75%). The initial response rate to recruitment was 54.6%. A total of 92.3% of participants remained in the study in 2015, and interview response rate was between 80.2% and 85.6% yearly. Table I describes demographic information for our participants.

Table I.

Participant demographics for 319 college students from 2 universities

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 179 (56.1) |

| Male | 140 (43.9) |

| University | |

| Northwest | 131 (41.1) |

| Midwest | 188 (58.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 240 (75.2) |

| Asian | 37 (11.6) |

| Hispanic | 10 (3.1) |

| More than 1 | 21 (6.6) |

| African-American/black | 5 (1.6) |

| East Indian | 3 (0.9) |

| Other | 2 (0.6) |

| Native American/Alaska | 1 (0.3) |

Prevalence Estimates of Problematic Internet Use over Time

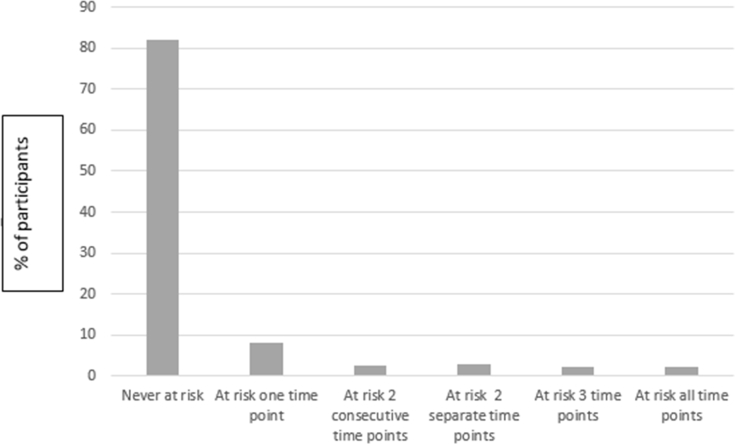

Across the 4 years of the study, the problematic internet use prevalence estimates varied between approximately 9% and 11%. The greatest prevalence estimate was 11.1% at the end of year 4 (Table II). We found no statistically significant differences (P = .34) in prevalence estimates of problematic internet use over time. Overall, 29 (9%) of participants were at risk at multiple time points. Figure 1 illustrates the frequency of participants at risk across one or multiple time points.

Table II.

Prevalence of problematic internet use over 4 years among college students from 2 universities

| Time points | n (%) | 95% LCL | 95% UCL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | 26 (9.2) | 6.3 | 13.1 |

| Year 2 | 26 (9.2) | 6.3 | 13.2 |

| Year 3 | 28 (10.6) | 7.4 | 14.9 |

| Year 4 | 29 (11.1) | 7.8 | 15.5 |

Figure 1.

Frequency of participants at risk for problematic internet use across 1 or more time points across 4 years of college.

Predictors of Problematic Internet Use over Time

Within our multivariate model, only problematic internet use status from the previous time period was identified as a significant predictor for problematic internet use risk at the current time period (OR 24.1, 95% CI 12.8-45.4, P < .0001). Sex, race, and university were not significant predictors of subsequent problematic internet use risk.

Defining an Intermediate-Risk PRIUSS Score

The receiver operating curve for the intermediate-risk score that was associated with subsequent development of problematic internet use risk is shown in Figure 2. The optimal threshold for defining intermediate risk was a PRIUSS score of 15. At this score, the sensitivity was 89.6 and the specificity was 72.9. The positive predictive value was 13.3 and the negative predictive value was 99.4. Youden criteria was 62.6. In contrast, a PRIUSS score of 14 had a Youden criteria of 58.8.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curve for the intermediate PRIUSS risk score that was associated with subsequent development of problematic internet use risk.

Transitions between Risk States

On the basis of the results for an intermediate-risk PRIUSS score, multistate Markov modeling defined high risk as a PRIUSS score of 26 or greater, intermediate risk was defined as a score of 15-25, and low risk was defined as a score of 14 or lower. Markov modeling revealed that although many participants remained at low risk throughout the longitudinal study, moving to intermediate risk was highly predictive of progressing to high risk. Figure 3 illustrates the path of these transitions.

Figure 3.

Markov model: This model illustrates the direction and proportion of participants moving through 3 different problematic internet use at risk states (low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk) over 4 time points.

Discussion

This study illustrates the prevalence estimates and predictors of problematic internet use over a 4-year time period among college students from 2 universities. We found that the mean prevalence estimate of problematic internet use over time had little variation—it remained between 9% and 11%. This finding suggests that there is not a single unique time point in college at which problematic internet use risk is significantly greatest compared with other time points. However, the prevalence estimates of 9%-11% throughout college in our sample appears at the greater end in comparison with previously reported in US samples.18 The nearly ubiquitous presence of wireless internet access, smartphones, and interactive media use among current college students19, 20 may be contributing to a rise in problematic internet use rates, or there may be other factors that explain this greater prevalence estimate.

Our study results indicated that no single demographic predictor identified college students at risk for problematic internet use. This finding is in contrast with earlier studies of problematic internet use that frequently identified males as a salient population at risk.10, 11 Our data are intriguing in that female and male students were both at risk. This finding may suggest that we were underpowered to detect subtle differences but also may be explained by the nearly universal engagement in internet-based technology among today's college students.19, 20

Findings also illustrated that participants moved in and out of being at risk for problematic internet use over time, as seen in Figure 1. This finding suggests that for some participants, problematic internet use may occur at a single time point in which psychosocial risk factors such as loneliness or stress14 intersect with a particular difficult semester or time period. In that time period, problematic internet use may manifest and then resolves as the situation improves. However, we also found that many participants were at risk for problematic internet use at more than 1 time point, both consecutively and separately. This suggests that the psychosocial risk factors for problematic internet use may be triggered at different time points and may benefit from intervention approaches to stop the cycle of problematic internet use.

We found that the most salient predictor of problematic internet use was being at risk at the previous time point. Thus, an intermediate-risk score cut-off for the PRIUSS scale may assist in earlier identification of college students at risk for developing problematic internet use. On the basis of data from this study, we propose an intermediate-risk cut-off of 15. As PRIUSS scores can range from 0 to 72, evidence supports that intermediate risk for problematic internet use be defined as scores of 15-25, and high risk for problematic internet use be defined as scores of 26 and greater. By refining this scale, we hope that this validated tool can be used to identify those at intermediate risk for problematic internet use and consider early prevention approaches.

Our study is not without limitations. Although the sample is representative of the colleges from which the data were drawn, the sample is not representative of all colleges, especially those with more racially and ethnically diverse students. Our ascertainment of all interview variables was limited to self-report, creating the possibility for recall and social desirability bias. We collected limited demographic information, additional measures of interest such as socioeconomic status, academic achievements, specific internet activities, or other health behaviors would have enhanced our understanding of risks for problematic internet use. Future studies could consider these additional measures. Further, our study selected the PRIUSS assessment tool, given it has a theoretical background14 and psychometric properties.6, 7, 21 However, other instruments to measure problematic internet use exists in the literature.22, 23 As with other longitudinal studies, missing data were present in our study. Our sensitivity analysis did not indicate concerns with the validity of our findings based on missing data. It is also important to recognize that controversy around problematic internet use still exists in the literature; one report described a European research network on problematic internet use and highlighted research needs including a need for interventions, policy approaches.24

Despite these limitations, our study has important implications. Understanding problematic internet use as a public health concern that reaches across sex and racial/ethnic groups can contribute to our understanding of problematic internet use as a critical clinical issue for today's adolescents and young adults. The finding of problematic internet use prevalence estimates between 9% and 11% in our study suggests that this is a public health issue with prevalence rates similar to other common illnesses in this population, such as depression.25 Thus, our study findings support screening of all adolescents and young adults for problematic internet use on a regular basis regardless of demographic characteristics. Use of the brief PRIUSS-3 scale,21 followed by the full PRIUSS-18 for those who screen positive, may help integrate problematic internet use screening into busy clinical practices in a consistent and efficient manner. Application of the intermediate-risk category for the PRIUSS may assist in identifying those who are likely to develop problematic internet use, and prompt a prevention plan. Although there are no current validated interventions for problematic internet use, it is possible that working with college students at intermediate risk may allow modification of technology behaviors to prevent the onset of problematic internet use. One potential tool that clinicians can use in these patient care scenarios is the American Academic of Pediatrics Family Media Use Plan (https://www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx).26 Recent evidence suggests this tool may reduce certain problematic internet use symptoms, including social anxiety when away from the internet and withdrawal from the internet.27 This study did not evaluate potential problematic internet use prevention approaches, and this area of research is needed urgently to advance the field. Future studies may use the intermediate-risk cutoff for the PRIUSS to identify adolescents and young adults who may benefit from a preventive problematic internet use intervention.

Footnotes

Funded by the Common Fund (R01DA031580), managed by the OD/Office of Strategic Coordination (OSC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Moreno M.A., Jelenchick L.A., Christakis D.A. Problematic Internet Use Among Older Adolescents: A Conceptual Framework. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29:1879–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derbyshire K.L., Lust K.A., Schreiber L.R., Odlaug B.L., Christenson G.A., Golden D.J., et al. Problematic Internet use and associated risks in a college sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yen J.Y., Ko C.H., Yen C.F., Wu H.Y., Yang M.J. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko C.H., Yen J.Y., Chen C.S., Yeh Y.C., Yen C.F. Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for Internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:937–943. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam L.T., Peng Z.-W. Effect of pathological use of the Internet on adolescent mental health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:901–906. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jelenchick L.A., Eickhoff J., Christakis D.A., Brown R.L., Zhang C., Benson M., et al. The Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS) for adolescents and young adults: scale development and refinement. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;35:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelenchick L.A., Eickhoff J., Zhang C., Kraninger K., Christakis D.A., Moreno M.A. Screening for adolescent problematic internet use: validation of the Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS) Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jelenchick L.A., Christakis D.A., Moreno M.A. Pediatric Academic Societies; Vancouver, BC: 2014. A longitudinal evaluation of Problematic Internet Use (PIU) symptoms in older adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelenchick L.A., Christakis D.A., Moreno M.A. Excellence in Paediatrics; Doha, Qatar: 2013. The problematic and risky Internet Use Screening Scale: A confirmatory factor analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao H., Sun Y., Wan Y., Hao J., Tao F. Problematic Internet use in Chinese adolescents and its relation to psychosomatic symptoms and life satisfaction. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:802. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J., Shen L.X., Yan C.H., Hu H., Yang F., Wang L., et al. Personal characteristics related to the risk of adolescent Internet addiction: a survey in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelenchick L.A., Hawk S.T., Moreno M.A. Problematic Internet use and social networking site use among Dutch adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;28:119–121. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2014-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banyai F., Zsila A., Kiraly O., Maraz A., Elekes Z., Griffiths M.D., et al. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno M.A., Jelenchick L.A., Christakis D.A. Problematic Internet use among older adolescents: a conceptual framework. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29:1879–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro D.E. The interpretation of diagnostic tests. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:113–134. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welton N., Ades A. Estimation of Markov chain transition probabilities and rates from fully and partially observed data: uncertainty propagation, evidence synthesis, and model calibration. Medical Decision Making. 2005;25:633–645. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berglund P., Herringa S. SAS Institute Inc; Cary (NC): 2014. Multiple imputation of missing data Using SAS. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christakis D.A., Moreno M.M., Jelenchick L., Myaing M.T., Zhou C. Problematic Internet usage in US college students: a pilot study. BMC Med. 2011;9:77. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith A. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington (DC): 2015. US smartphone ownership 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duggan M. Pew Internet and American Life Profject; Washington (DC): 2015. Mobile messaging and social media 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno M.A., Arseniev-Koehler A., Selkie E. Development and testing of a 3-item screening tool for problematic Internet use. J Pediatr. 2016;176:167–172 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loconi S., Rodgers R.F., Chabrol H. The measurement of Internet addiction: a critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:190–202. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno M.A., Jelenchick L., Cox E., Young H., Christakis D.A. Problematic Internet use among US youth: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:797–805. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fineberg N.A., Demetrovics Z., Stein D.J., Ioannidis K., Potenza M.N., Grunblatt E., et al. Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the Internet. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1232–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewinsohn P.M., Rohde P., Seeley J.R. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Academy of Pediatrics Family Media Use Plan 2016. https://www.healthychildren.org/english/media/pages/default.aspx Accessed February 2, 2019.

- 27.Moreno M.A., Gower A.D. Society for Research on Child Development; Baltimore (MD): 2019. A pilot online intervention for problematic Internet use symptoms among early adolescents. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.