Abstract

We report the case of a 54-year-old male who presented with complaints of decreased vision in the left eye (LE). He gave a history of multiple bee stings following which he had an episode of allergic anaphylaxis to the face and neck region for which he was admitted and treated with steroids. On examination, he was found to have LE central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) which was the cause of his reduced vision. This is the first report of a bee sting venom as a cause for CRAO.

Keywords: Bee sting, central retinal artery occlusion, Kounis syndrome

Introduction

Bee sting, a common environmental injury encountered worldwide, usually causes minor local allergic reactions and rarely anaphylactic or delayed hypersensitivity reactions due to inoculation of bee venom.[1] Systemic complications are even rare and usually result from multiple bee stings causing massive envenomation. Acute coronary syndrome, acute renal failure, stroke, and even death are reported as severe complications of multiple bee stings.[1,2]

Bee sting-related ocular injuries are uncommon and mainly result from direct bee sting on ocular surfaces such as cornea and bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva.[3] Various ocular complications reported in literature are corneal epithelial defect, corneal stromal infiltration, endothelial cell loss, heterochromia irides, glaucoma, and cataract. The other reported visually debilitating complications include uveitis, optic neuritis, external and internal ophthalmoplegia, optic atrophy, and papillitis.[3,4]

We report the first case of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) attributed to large-dose envenomation from multiple bee stings.

Case Report

A 54-year-old man came to our outpatient department with a history of reduced vision in the left eye (LE) of 1-week duration. He had a history of severe allergic anaphylaxis following multiple bee stings on the face and neck region, which was managed medically with intravenous steroid and antihistamine at a local hospital. During the 2nd day of treatment, he noticed defective vision in the LE which progressively worsened. He was on oral steroids when he presented to us.

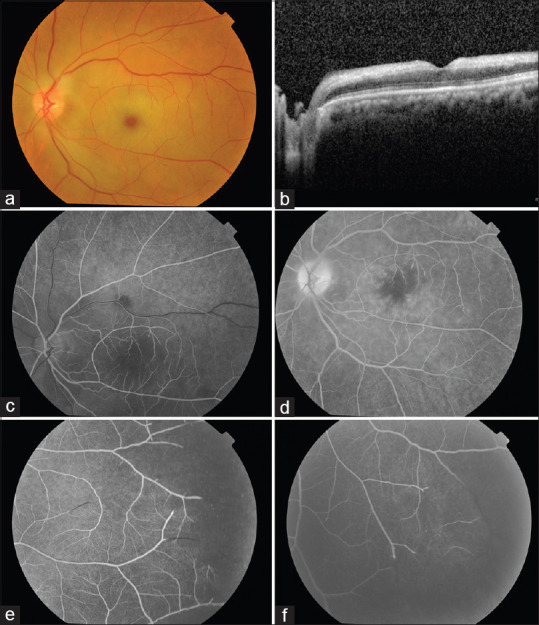

On examination, his best-corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/12 and perception of light in the LE. Anterior segment examination showed relative afferent pupillary defect in LE and early immature cataract in both eyes. Fundus examination of LE showed resolving ischemic edematous retinal whitening with cherry-red spot at the fovea. An unusual arterial supply was observed with the inferotemporal branch retinal artery also supplying the superior quadrant [Figure 1a]. Fundus of RE was within normal limits. Optical coherence tomography of LE showed normal foveal contour with hyperreflective inner retinal layers suggestive of ischemic edema [Figure 1b]. Fundus fluorescein angiogram (FFA) was done which revealed a delayed arm-to-retina time of 25 s in the LE. Early phases of the FFA revealed enlarged foveal avascular zone (FAZ) suggestive of ischemic macula [Figure 1c], late phase showing diffuse edema around the FAZ [Figure 1d]. Mid-phase images of the periphery showed incomplete peripheral arterial filling with large capillary nonperfusion areas [Figure 1e and f]. His systemic workup including complete hemogram, coagulation profile, renal and hepatic function, carotid Doppler, and echocardiography was within normal limits. Based on the multimodal imaging features, a diagnosis of CRAO in the LE was made, and he was started on oral aspirin (75 mg) once daily. The patient lost to further follow-up.

Figure 1.

(a) Fundus photograph of the left eye shows a cherry-red spot at the macula. Note the unusual supply to the superior quadrant from the inferotemporal branch retinal artery; (b) Optical coherence tomography macula showing retinal inner layer hyperreflectivity due to retinal edema; (c) Early phase of fundus fluorescein angiogram showing enlarged foveal avascular zone suggestive of ischemic macula; (d) Late phase showing diffuse leakage due to retinal edema. Note the incomplete terminal filling of the branch arteries supplying the macula; (e and f) Fundus fluorescein angiogram of the peripheral retina showing incomplete arterial filling with large capillary nonperfusion areas

Discussion

The clinical manifestations of bee sting are divided into three groups: local allergic reactions, immunological reactions usually leading to anaphylaxis, and systemic toxic reactions caused by large dose of venom from multiple bee stings.[1] The main toxic components of bee venom include biologic amines such as histamine, dopamine, and norepinephrine; nonenzymatic polypeptide toxins such as melittin, apamin (neurotoxin), peptide 401, and mast cell degranulating peptide; and high-molecular-weight enzymes such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and B (PLB) and hyaluronidase.[1]

Severe systemic complications following multiple bee stings are sparsely reported in literature including acute coronary syndrome, stroke, acute renal failure, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, nephrosis, serum disease, and peripheral neuropathy after bee stings.[1] Cardiovascular events such as acute coronary syndrome and stroke can develop either secondary to anaphylaxis or as a delayed complication due to the direct toxin reactions.[1,5] During anaphylaxis, various biologic amines act as a vasoactive mediator causing peripheral vasodilatation and hence deep hypotension, while vasoconstricting effect on coronary circulation increases myocardial oxygen demand leading to myocardial ischemia. PLA2, a constituent of bee venom, activates the metabolism of the arachidonic acid resulting in release of leukotrienes by the lipoxygenase pathway and prostaglandins such as thromboxane by cyclooxygenase pathway. These mediators have been incriminated to induce coronary artery spasm and/or allergic acute myocardial infarction called Kounis syndrome.[2] Envenomation by multiple bee stings is also known to produce a hypercoagulable state and platelet aggregation due to thromboxane A2 and phospholipase activation.

There are limited literature describing the ocular complication of bee sting. Majority of the reported ocular complications have resulted from direct ocular bee sting. Melittin and biologic amines cause initial inflammatory response manifesting as congestion and chemosis.[3] The nonenzymatic polypeptide toxins cause membrane disruption, hemolysis, and protein denaturation resulting in corneal endothelial cell damage, glaucoma, cataract formation, and zonular dialysis.[3] The immune reaction in the cornea causes edema, and the sterile infiltrates, especially around the stinger. Degeneration of chromatophores of anterior iris layers induced by PLA2, PLB, and hyaluronidase manifests as heterochromia.[3] The visually debilitating complications such as optic neuritis, external and internal ophthalmoplegia, optic atrophy, and papillitis are reported to be due to the neurotoxic effect of apamin and other components of bee venom inducing increased free oxygen radical formation.[4] Rishi and Rishi have reported a case of ocular bee sting injury-causing anterior uveitis, vitritis, and ciliochoroidal detachment, mimicking endophthalmitis with a good visual outcome 3 weeks following treatment with systemic steroids.[6]

Our patient developed anaphylaxis and systemic hypotension following the incidence, for which he was treated with systemic steroids. However, he was not given any anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy. His systemic workup including blood investigations, carotid Doppler, and echocardiography was within normal range at 1 week following the incidence, which might be attributed to steroid-induced resolution of allergic and toxic reactions. The exact pathogenesis of CRAO in our case is not clear, however we speculate various possible hypotheses for this unusual complication following multiple bee stings. A transient vasospasm of the central retinal artery via the Kounis reaction following bee stings appears as the most likely mechanism of CRAO. A transient hypercoagulable state caused by large-dose envenomation is another possible mechanism. Thrombotic events either due to direct toxin effect or toxic vasculitis may also be responsible for this vascular complication.

To conclude, this is the first case of CRAO following multiple bee stings. An ocular examination with dilated fundus evaluation must be considered during initial assessment following bee sting, especially in case of large-dose envenomation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the technical support provided by Miss Ramalakshmi P and Miss Sharmila K by helping us acquire the images.

References

- 1.Laxmegowda, Ranjith V, Keerthiraj D B, Pradeep B K. Retrospective study on complications of bee sting in a tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Contemporary Medical Research. 2018;5:G8–G10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aminiahidashti H, Laali A, Samakoosh AK, Gorji AM. Myocardial infarction following a bee sting: A case report of Kounis syndrome. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19:375–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.179626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudiseva H, Uddaraju M, Pradhan S, Das M, Mascarenhas J, Srinivasan M, et al. Ocular manifestations of isolated corneal bee sting injury, management strategies, and clinical outcomes. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:262–8. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_600_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi MY, Cho SH. Optic neuritis after bee sting. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2000;14:49–52. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2000.14.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nisahan B, Selvaratnam G, Kumanan T. Myocardial injury following multiple bee stings. Trop Doct. 2014;44:233–4. doi: 10.1177/0049475514525606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rishi E, Rishi P. Intraocular inflammation in a case of bee sting injury. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2018;8:Doc02. doi: 10.3205/oc000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]