Abstract

Most research and theory on identity integration focuses on adolescents and young adults under age 30, and relatively little is known about how identity adjusts to major life events later in life. The purpose of the present study was to operationalize and investigate identity disruption, or a loss of temporal identity integration following a disruptive life event, within the developmental context of established adulthood and midlife. We used a mixed-methods approach to examine identity disruption among 244 Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans with reintegration difficulty who participated in an expressive writing intervention. Participants completed measures of social support, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty at baseline right before writing, and 3 and 6 months after the expressive writing intervention. The expressive writing samples were coded for identity disruption using thematic analysis. We hypothesized that identity disruption would be associated with lower social support, more severe PTSD symptoms, lower satisfaction with life, and greater reintegration difficulty at baseline. Forty-nine percent (n = 121) of the sample indicated identity disruption in their writing samples. Identity disruption was associated with more severe PTSD symptoms, lower satisfaction with life, and greater reintegration difficulty at baseline, and with less improvement in social support. The findings suggest that identity disruption is a meaningful construct for extending the study of identity development to established adult and midlife populations, and for understanding veterans’ adjustment to civilian life.

Keywords: temporal identity, identity development, life events, veterans, mental health, social support

Identity can be conceptualized broadly as the sense of self: the roles, traits, goals, values, beliefs, and experiences that add up to create an individual’s unique place in the world (Schwartz, Luyckx, & Crocetti, 2015; Syed & McLean, 2016). According to Erikson (1968), identity development is a continuous process that extends over the course of an individual’s lifetime. However, the overwhelming majority of research on identity development focuses on the processes of identity formation that take place in adolescence and emerging adulthood (e.g., Syed & McLean, 2016; Vignoles et al., 2011). In comparison, the developmental processes involved in maintaining a healthy identity over the course of the adult lifespan have been relatively neglected (Kroger, 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015; Whitbourne, Sneed, & Skultety, 2002). There is, therefore, a significant gap in our understanding of how identity responds to the myriad life challenges faced after adolescence and across the lifespan.

The present study investigated identity concerns among adults, with an emphasis on two life stages that historically have been neglected across the developmental and identity development literatures: established adulthood and midlife (Arnett & Schwab, 2014; Lachman, 2004; Lachman, Teshale, & Agrigoroaei, 2015; Mehta, Arnett, Palmer, & Nelson, 2019). Established adulthood, defined as the time of life from roughly age 25–39, is characterized by a focus on developing close and enduring relationships, deepening commitments to one’s career, and raising a family (Arnett & Schwab, 2014; Mehta et al., 2019). These commitments are further strengthened in midlife (between ages 40–59 or so; Lachman et al., 2015), which is typically a time of peak power and responsibility (Lachman, 2004). Individuals tend to reach the height of their careers and financial stability at this time of life. They are also often caring for children and aging parents simultaneously, and dealing with emerging health conditions associated with their own aging. Under normal circumstances, identity remains fairly stable across these stages of life, and most adults are able to maintain a continuous sense of self that gradually adjusts in relation to their life experiences (Brandstadter & Greve, 1994; Carlsson et al., 2015; McAdams, 2001).

However, changing life circumstances may interfere with self-continuity, even during adult life stages that are thought of as relatively stable in terms of identity. In the present study, we introduce identity disruption as a novel construct reflecting discontinuities in identity that arise in response to major life changes. Disruptive events can call existing identities into question, and require individuals to reconfigure their identities in light of new conditions (Habermas & Kober, 2015). Research from the narrative identity perspective has documented that major life transitions, such as religious conversions and career shifts (Bauer & McAdams, 2004), divorce (King & Raspin, 2004), and bereavement (Baddeley & Singer, 2010), may trigger changes in the sense of self. Much of this literature has focused on the way that individuals frame and narrate their experiences of such events, demonstrating that individuals who integrate disruptive events into their life narratives – by actively reflecting on events, making meaning of them, and finding positive resolutions – tend to have greater well-being (Lilgendahl, 2015). However, less research has examined the downstream consequences of failing to integrate disruptive events into one’s identity during different phases of adulthood. Thus, whereas the benefits of integrating challenging experiences into one’s life story are well-articulated, it is less clear what happens when individuals have persistent difficulty finding a positive, coherent resolution and re-establishing a sense of self-continuity. Given the range of disruptive events that adults may face across the lifespan, understanding the potential identity-related problems that may arise in response to disruptive events at various stages of adulthood is crucial.

Temporal identity integration is a key aspect of identity that may be affected by major life changes across adulthood. Identity integration refers to a subjective sense of self-continuity and coherence, and developing and maintaining an integrated identity is seen as a sign of healthy identity development (Syed & McLean, 2016). Temporal identity integration, also known as self-continuity (Becker et al., 2018) or continuous identity (Sokol & Eisenheim, 2016), is a specific aspect of identity integration, capturing the degree of connectedness between one’s past, present, and future selves over time (Syed & Mitchell, 2015). Temporal integration is distinct from other aspects of identity integration such as contextual integration, which refers to the sense of continuity across different life roles (e.g., career, relationships), and from sociocultural integration, which refers to the fit between an individual and his or her sociocultural environment (Syed & McLean, 2016). Although most research on identity integration focuses on contextual integration, temporal integration has drawn increasing scholarly attention. Recent efforts include charting how temporal integration develops across the lifespan (Rutt & Lockenhoff, 2016), and comparing temporal integration across cultural contexts (Becker et al., 2018). A growing body of evidence also demonstrates connections between temporal integration and psychosocial outcomes. For example, higher temporal identity integration was associated with well-being and positive psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Benish-Weisman, 2009; McAdams, 2013; Waters & Fivush, 2015) whereas lower temporal identity integration was associated with poorer mental health, including depression (Baerger & McAdams, 1999; Sokol & Serper, 2017) and increased risk of suicidality (Chandler, Lalonde, Sokol, & Hallett, 2003; Sokol & Eisenheim, 2016).

The consequences of challenging life events for temporal identity integration can be studied in adult populations undergoing a major life transition or stressor. We examined these issues among U.S. military veterans who reported difficulty reintegrating into civilian life after combat deployments. This seemed particularly apt in light of the fact that veterans are historically an important population in the identity literature, as much of Erikson’s (1968) original theory was informed by his early clinical work with veterans of World War II (Erikson, 1946; Syed & McLean, 2016). Additionally, research has shown that many more recent veterans report identity-related challenges in the course of reintegrating back into civilian life (Keeling, 2018; Orazem et al., 2017; Smith & True, 2014), despite many of them being older than the age groups that are typically studied in the identity literature. For example, in 2009, midway through U.S. military engagement in Afghanistan and Iraq, approximately 49% of active duty service members were between ages 25–39, and another 9% were between ages 40–54 (Institute of Medicine, 2010). For such individuals, who have often spent a significant portion of their early adult lives as service members, reintegration may present challenges to central aspects of identity. Furthermore, reintegration often involves a range of discontinuities, including job changes, relocation, and separation from military friends (Demers, 2011; Sayer, Noorbaloochi, Frazier, Carlson, Gravely, & Murdoch, 2010), which may threaten veterans’ existing identities. Thus, veterans transitioning to civilian life represent an ideal case for better understanding how adults’ identities at these developmental phases are affected by changing life circumstances.

The present study integrates a lifespan development perspective into the study of identity by examining how identity may be disrupted among adults, especially at the established and midlife phases of adulthood. We used data collected as part of a randomized controlled trial of an expressive writing intervention for veterans with difficulty reintegrating into civilian life (Sayer et al., 2015). Thus, the sample was drawn from a population of adults who were having difficulty in response to a major life stressor. In expressive writing, individuals are asked to reflect on meaningful life experiences, and to write about their thoughts and feelings around such events (Baddeley & Pennebaker, 2011). The resulting written material often includes information about how one’s identity was affected by important life experiences. The writing samples also offered the opportunity to identify identity-related themes that were salient to participants without prompting from a researcher and thus may be particularly meaningful and tied to psychosocial outcomes.

The first objective of this study was to create an operational definition for identity disruption, i.e., a loss of temporal identity integration associated with changing life circumstances. Erikson’s (1968) lifespan theory of identity development suggests that major life events, such as reintegration after combat deployment, may challenge an individual’s sense of temporal identity integration. To clarify how veterans’ temporal identities may be affected by reintegrating into civilian life, we used thematic analysis to generate themes that reflected common experiences of identity disruption. These identity disruption themes capture common patterns in the subjective experience of a threat to one’s temporal identity integration.

The second objective of this study was to examine the relations between identity disruption and psychosocial outcomes relevant to veterans’ adjustment. Specifically, we tested the association between identity disruption and social support, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that quantitatively assessed the relations between veterans’ identity and mental-health constructs. We hypothesized that veterans reporting identity disruption would report lower levels of social support and satisfaction with life, and higher levels of PTSD symptom severity and reintegration difficulty at baseline. We also explored the association between identity disruption and longitudinal mental-health trajectories after expressive writing to inform future research on identity and mental health.

Method

Participants and Study Design

The data for the present study were drawn from the Military to Civilian Study (Sayer et al., 2015). The purpose of the parent study was to assess the efficacy of expressive writing about reintegration difficulties in a veteran sample, using a randomized controlled trial. A random sample of Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans identified through government rosters (N = 15,686) were assessed for eligibility via mailed questionnaires. Notably, veterans were eligible for the study if they reported at least “a little” reintegration difficulty and had a phone and internet access; those with severe depression were excluded. Women were oversampled in the recruitment process, and gender was used as a blocking factor to evenly distribute assignment of men and women to the three conditions (see Sayer et al., 2015, for full details on recruitment procedures).

Eligible veterans (N = 3,645) were invited to complete an online consent form, and those who chose to participate (N = 1,292) were randomized to one of three study conditions: Expressive Writing (n = 508), Control Writing (n = 507), or No Writing Control (n = 277). The present study used quantitative and qualitative data from a subgroup of participants in the Expressive Writing condition, because the Expressive Writing prompt was designed to elicit personal thoughts and feelings, including those related to identity (see writing prompt below) and thus would provoke consideration of identity-related concerns. Participants in the Control Writing group were asked to write factually about veteran information needs, and thus their writing samples were generally not identity-related. As the present study involved secondary analysis of existing, de-identified data, this study was considered exempt by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (Study #1703E09041, “Military to Civilian: Social Reintegration After Deployment”). Quantitative data on psychosocial outcomes were collected at baseline, and 3- and 6-months after the expressive writing intervention.

The present study sample of 244 participants included 59% men and 40% women, who were primarily White (66%), and there were a substantial number of Hispanic (14%) and Black (14%) participants. About 52% had a college diploma or advanced degree. The average age was 38.8 years (SD = 10.6) and age ranged from 23 to 67, and the average time since deployment was 6.2 years (SD = 2.5). Further demographic details are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Descriptive Statistics for Outcomes

| Category | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 145 | 59.4 | - | - |

| Female | 99 | 40.6 | - | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic | 210 | 86.1 | - | - |

| Hispanic | 34 | 13.9 | - | - |

| Race | ||||

| White | 162 | 66.4 | - | - |

| Black | 35 | 14.3 | - | - |

| Asian | 7 | 2.9 | - | - |

| Multiracial | 9 | 3.7 | - | - |

| Native American | 3 | 1.2 | - | - |

| Unknown | 28 | 11.5 | - | - |

| Degree | ||||

| GED or High School Diploma | 15 | 6.1 | - | - |

| Some college or post high school training | 94 | 38.5 | - | - |

| College Diploma | 89 | 36.5 | - | - |

| Advanced degree | 38 | 15.6 | - | - |

| Other | 8 | 3.3 | - | - |

| Income | ||||

| $0–$10 000 | 10 | 4.1 | - | - |

| $10 000 to $20 000 | 19 | 7.8 | - | - |

| $20 000 to $40 000 | 61 | 25.0 | - | - |

| $40 000 to $60 000 | 45 | 18.4 | - | - |

| More than $60 000 | 91 | 37.3 | - | - |

| Missing/Prefer not to answer | 18 | 7.4 | - | - |

| Parenthood | ||||

| Has no children | 75 | 30.7 | - | - |

| Has children | 169 | 69.3 | - | - |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Never married/single | 42 | 17.2 | - | - |

| Married/partnered | 156 | 63.9 | - | - |

| Divorced/separated | 46 | 18.9 | - | - |

| Branch | ||||

| Army | 133 | 54.5 | - | - |

| Air Force | 46 | 18.9 | - | - |

| Navy | 38 | 15.6 | - | - |

| Marine | 27 | 11.1 | - | - |

| Rank | ||||

| Enlisted | 190 | 77.9 | - | - |

| Officer | 49 | 20.1 | - | - |

| Warrant | 5 | 2.0 | - | - |

| Component | ||||

| Active Duty | 134 | 54.9 | - | - |

| Reserves/National Guard | 98 | 40.2 | - | - |

| Other | 12 | 4.9 | - | - |

| Age | - | - | 38.78 | 10.60 |

| Deployments | - | - | 1.10 | 1.06 |

| Time Since Deployment | - | - | 6.23 | 2.51 |

| Combat Exposure | - | - | 4.84 | 4.02 |

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information gathered at baseline included: ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic or non-Hispanic), race (i.e., White, Black, Asian, Native American, Multiracial, or Unknown), highest degree obtained, annual household income, parental and marital status, military branch (e.g., Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine), rank (i.e., enlisted, officer, or warrant officer), and component (i.e., active duty, Reserves/National Guard, or other). Measures of sex, age, number of deployments, and time since most recent deployment were drawn from a Department of Defense/Department of Veterans Affairs roster.

Combat exposure.

The Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) Combat Exposure subscale (King, King, & Vogt, 2003), administered at baseline, is a 15-item checklist of deployment experiences designed for active duty service members and veterans. Participants indicated whether they had experienced events using “yes” or “no” responses. Participants were instructed to consider all prior combat experiences, if they had been deployed multiple times. A sample item is “I or members of my unit were attacked by terrorists or civilians.” The alpha coefficient at baseline was .88. This variable was used as a covariate in the quantitative analyses.

Perceived social support.

Perceived social support was measured at baseline, and 3-, and 6-months using the Post-Deployment Social Support Scale of the DRRI. This scale included 15 items measured on a 5-point scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). Participants were asked to focus on how they felt in the past month. A sample item was, “Among my friends or relatives, there is someone I go to when I need good advice.” Higher scores indicated greater perceived social support. Alphas at baseline, 3, and 6 months ranged from .79 to .84.

PTSD symptom severity.

PTSD symptom severity was measured at baseline, and 3-, and 6-months using the PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1995). Participants used a 5-point scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely) to respond to the 17 items, which corresponded to DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, indicating how much they had been bothered by each symptom in the past month. A sample item was, “Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts or images of a stressful military experience.” Alphas across the three time periods ranged from .95 to .96.

Satisfaction with life.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larson, & Griffin, 1985) was used to measure satisfaction with life at baseline, and 3-, and 6-months. This scale included five items, rated on a 7-point scale (0 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). Participants reported on their life satisfaction within the past two weeks. A sample item was, “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.” Higher scores indicated greater satisfaction with life. Alphas ranged from .90 to .92.

Reintegration difficulty.

The Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q; Sayer et al., 2011) measured community reintegration difficulty following deployment. It was administered at baseline, and 3-, and 6-months postintervention. Most of the 16 items were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = no difficulty; 4 = extreme difficulty), with some items including a “does not apply” response option. Items were presented with the prompt, “Over the past 30 days, have you had difficulty with…” Sample items included “Making new friends” and “Doing what you need to do for work or school.” Higher scores on the M2C-Q indicated greater difficulty with the reintegration transition. Alphas across the three time periods ranged from .77 to .81.

Expressive Writing Prompt

Participants responded to the following expressive writing prompt, which was similar to the prompt used in a previous writing intervention with military couples (Baddeley & Pennebaker, 2011):

For the next 20-minutes, write about resuming civilian life after your military deployment…Try to explore your deepest thoughts and feelings about your transition to civilian life…Feel free to link your reintegration to events from your past, your present, or your future; to who you have been, who you are now, or who you would like to be. The important thing is that in your writing you allow yourself to explore your deepest thoughts and feelings.

Procedure

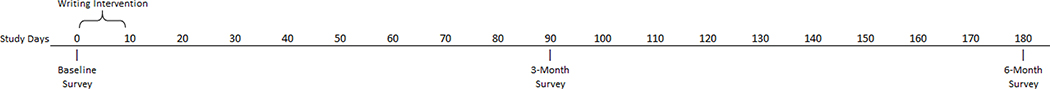

All participants completed study measures and expressive writing online. The timeline of the study is summarized in Figure 1. After the baseline assessment, participants were asked to complete four 20-minute writing sessions at times convenient to them. They could schedule their writing sessions over 10 days after their baseline assessment, but most participants elected to complete their writing sessions on consecutive days right after the baseline assessment (median number of days between sessions = 1). Participants were not permitted to move forward in the online survey until 20 minutes had elapsed. Participants were informed that they should not worry about spelling, grammar, or repetition in their writing, that their writing would be kept confidential, and that they would not receive any feedback or follow-up on their writing unless it included plans to harm themselves or someone else.

Figure 1.

Study Timeline.

Note. This figure illustrates the timeline of the study, to scale.

Given the aims of the present study included operationalizing a new identity construct, we opted to include only those participants with all four writing sessions completed, as they had more opportunity to express identity-relevant issues in their writing. It may take several writing sessions for veterans to explore their deeper thoughts and feelings and thus to discuss identity-related concerns. Including participants who completed all four sessions ensured that all participants had a comparable and lengthy amount of time to write expressively about reintegration, optimizing the chance that, if they had identity concerns to discuss, such concerns would appear in their writing samples. Thus, this study included only the 244 out of 508 (48%) expressive writing participants who completed all four writing sessions. The 244 who completed all four writing sessions did not differ significantly from the 264 who completed fewer sessions in terms of sex, ethnicity, race, income, parental status, marital status, military branch, number of deployments, level of combat exposure, or baseline levels of social support, PTSD symptom severity, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty, all ps > .05. However, the group completing all four writing samples had modestly higher educational achievement (a difference of 0.28 points on the 4-point educational attainment measure used, t (498) = 3.47, p < .001), were more likely to be officers, χ2 (2) = 13.37, p = .001, were about four years older on average, t (480) = 4.33, p < .001, and had an average of 6.2 years since their last deployment, compared to 5.8 years for the group completing fewer sessions, t (502) = 2.10, p = .04).

Qualitative Coding and Analysis

The coding strategy was adapted from Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method for thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a relatively flexible form of qualitative analysis, and has been used in prior research to analyze data generated through similar writing interventions to better understand the lived experiences of individuals who completed the intervention (e.g., Abreu, Riggle, & Rostosky, 2020; Carrico et al., 2015; Carrillo, Martinez-Sanchis, Echtemendy, & Banos, 2019; Rawlings, Brown, Stone, & Reuber, 2017). Because identity disruption was a novel construct, our first step was to develop themes that thoroughly characterized the subjective experience of identity disruption, based on participants’ reports of their identity-relevant experiences. We began with a relatively simple operational definition for identity disruption, and through qualitative analysis, developed detailed themes that reflected the common patterns in how veterans actually described changes in their identities, which they attributed to reintegration and leaving the military. Beginning with the theoretically-founded idea that major life events such as returning to civilian life may pose a threat to identity integration, the members of the coding team (the first author and four trained undergraduate coders) first read subsets of the qualitative data in sets of 30 responses at a time to identify those with relevant identity content. Responses that included content related to identity disruption (i.e., responses that included information relevant to changes in identity and self-concept, which participants linked to their reintegration experience) were flagged for discussion and further analysis. The coding team met weekly to review these responses and to create “captions” for them, boiling down the identity-relevant information in each response into a short description that captured the participant’s subjective experience of identity disruption. Examples included, “I feel like everything I have been working toward is over,” and “It’s hard for me to readjust to who I was before.” We continued to read responses and add captions to the list until we found that our list of captions represented the majority of participants’ experiences, and no new captions were needed (i.e., saturation had been achieved; Dey, 1999; Saunders et al., 2018). We collected these captions and searched for patterns, grouping them into four overarching themes based on the underlying meaning of the captions. These themes are described in detail in the results section.

After establishing final definitions for the identity disruption themes, the coding system was applied to the entire dataset. The “master coder” strategy of establishing reliability was employed (Syed & Nelson, 2015), in which one member of the coding team (the first author) codes all of the data, and a reliability coder codes a subset of the data (in this case, 30 [12%] participants’ responses) to establish inter-rater reliability. Reliability was calculated at the writing sample level. Although kappa is often considered the “gold standard” among reliability indices, it is sensitive to the distribution of codes, is often attenuated by infrequently coded categories, and is less intuitive than percent agreement (e.g., different values of kappa may be obtained for the same level of percent agreement; Syed & Nelson, 2015). Therefore, we used both kappa and percent agreement as indices of reliability. Reliability estimates for identity disruption overall were kappa = .71, with 90% agreement. Estimates for the specific themes are provided in Table 2. Throughout the coding process, the master coder met with the other members of the coding team to discuss difficult responses and establish consensus on them.

Table 2.

Identity Disruption Themes.

| Theme | Loss of meaning or purpose | Disconnection between past, present, and future selves | Role disruption | Loss of self-worth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (N) | 67 | 67 | 82 | 34 |

| Reliability | ||||

| Kappa | .73 | .93 | .86 | .86 |

| Percent agreement | 87% | 97% | 93% | 93% |

| Co-occurrence with other themes | ||||

| Loss of meaning or purpose | - | 35 (52%) | 48 (59%) | 19 (56%) |

| Past, present, future selves | 35 (52%) | - | 39 (48%) | 21 (62%) |

| Role disruption | 48 (72%) | 39 (58%) | - | 21 (62%) |

| Loss of self-worth | 19 (28%) | 21 (31%) | 21 (26%) | - |

Note. Co-occurrence with other themes indicates the number of participants who reported both themes in their response (e.g., 35 participants indicated both a loss of meaning or purpose, and a disconnection between past, present, and future selves). Percentages in parentheses are the proportion of individuals within each column who also reported the theme indicated in the row (e.g., 28% of the 67 individuals who reported loss of meaning or purpose also reported loss of self-worth).

Themes were not intended to be mutually exclusive and many participants’ responses incorporated two or more of the four identity disruption themes. Eight (3%) participants included all four themes in their responses, 30 participants (12%) included three themes, 45 participants (18%) included two themes, and 38 (16%) included one theme. For the purposes of subsequent quantitative analyses, identity disruption was coded with a “1” if identity disruption was present and a “0” if identity disruption was absent, regardless of which of the four theme(s) were reflected in their responses. Data were coded at the writing session level, so that each participant received separate scores for the first, second, third, and fourth writing session. For quantitative analyses, we created a summary score across writing sessions, such that participants were scored as “1” if they reported identity disruption in any of their writing sessions. NVivo software (version 11; QSR International, 2015) was used to code the data, and the coding matrix was exported to SPSS version 24.0 for use in quantitative analysis.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between identity disruption themes and psychosocial outcomes, including social support, PTSD symptoms, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty. Such mixed-methods approaches to quantifying the associations between qualitatively-coded themes and quantitatively-measured outcomes of interest are regularly used in narrative identity research (e.g., Adler, 2012; McLean & Pratt, 2006; Syed & Azmitia, 2008), and have also been previously applied in the context of writing interventions (e.g., Carrillo et al., 2019).

Latent growth curve models (LGM) were used to fit trajectories of change in social support, PTSD symptoms, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty, and to compare the trajectories of individuals reporting identity disruption to those not reporting identity disruption. LGM is a form of structural equation modeling that involves estimating parameters, such as intercept and linear slope, to define trajectories of latent growth in observed variables (Singer & Willett, 2003; Tomarken & Waller, 2005). The general approach involves creating several models and selecting the one that best balances fit with parsimony.

We developed four sets of models to describe the relations between identity disruption and the four main outcomes of interest: social support, PTSD symptoms, satisfaction with life, and reintegration difficulty (see Table 3 for descriptive statistics for each outcome at each time point, and Table 4 for correlations among variables). For each outcome, we began by fitting an unconditional model to determine whether an intercept-only or linear functional form provided a better fit. Fit statistics, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), chi-square tests of model fit, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were used to identify the best fitting unconditional model (see Table 5; Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006). For AIC and BIC, lower values indicated a better fit. For the chi-square test, non-significant findings at p >.05 indicate good fit, though Hooper et al. cautioned that large sample sizes nearly always yield significant results for this test. RMSEA values should be less than .06, with a confidence interval reaching close to zero and no larger than about .08. For CFI, values greater than .95 indicate good fit, and for SRMR, values less than .08 are considered acceptable. We examined the pattern of results across the fit indices, and selected the unconditional form that resulted in the most favorable fit overall (i.e., better results on more indices, and minimizing violations of the rules described above).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Social Support, PTSD Symptoms, Satisfaction with Life, and Reintegration Difficulty

| Measure | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Social Support | 244 | 2.65 | .63 |

| 3-Month Social Support | 230 | 2.65 | .65 |

| 6-Month Social Support | 234 | 2.66 | .70 |

| Baseline PTSD Symptom Severity | 244 | 1.31 | .94 |

| 3-Month PTSD Symptom Severity | 231 | 1.22 | .94 |

| 6-Month PTSD Symptom Severity | 234 | 1.24 | 1.00 |

| Baseline Satisfaction with Life | 244 | 3.09 | 1.46 |

| 3-Month Satisfaction with Life | 231 | 3.18 | 1.49 |

| 6-Month Satisfaction with Life | 234 | 3.19 | 1.53 |

| Baseline Reintegration Difficulty | 244 | 1.38 | .89 |

| 3-Month Reintegration Difficulty | 230 | 1.33 | .93 |

| 6-Month Reintegration Difficulty | 234 | 1.36 | .97 |

Table 4.

Correlations among Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity disruption | - | |||||

| 2. Age | −.14* | - | ||||

| 3. Combat exposure | .001 | −.08 | - | |||

| 4. BL Social support | −.06 | −.04 | .04 | - | ||

| 5. BL PTSD symptom severity | .14* | .07 | .41*** | −.47*** | - | |

| 6. BL Satisfaction with life | −.15* | .01 | −.01 | .52*** | −.47*** | |

| 7. BL Reintegration difficulty | .18** | .07 | .14* | −.57*** | .76*** | −.61*** |

Note. N = 244.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

BL = Baseline.

Table 5.

Fit Indices for Latent Growth Curve Models

| Model | AIC | BIC | Chi square | RMSEA [CI] | CFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support | ||||||

| Unconditional intercept-only | 1050.75 | 1068.23 | χ2 (4) = 6.38, p = .17 | .049 [.000, .118] | .994 | .098 |

| Unconditional linear | 1050.37 | 1078.35 | χ2 (1) = .008, p = .93 | .000 [.000, .054] | 1.000 | .001 |

| Model 1 | 1051.75 | 1093.71 | χ2 (3) = 1.75, p = .63 | .000 [.000, .088] | 1.000 | .011 |

| Model 2 | 1049.61 | 1098.57 | χ2 (4) = 2.40, p = .66 | .000 [.000, .076] | 1.000 | .011 |

| PTSD Symptoms | ||||||

| Unconditional intercept-only | 1280.98 | 1298.46 | χ2 (4) = 10.93, p = .03 | .084 [.026, .146] | .990 | .057 |

| Unconditional linear | 1279.30 | 1307.28 | χ2 (1) = 3.26, p = .07 | .096 [.000, .221] | .997 | .012 |

| Model 1 | 1234.48 | 1276.44 | χ2 (3) = 4.66, p = .20 | .048 [.000, .127] | .998 | .011 |

| Model 2 | 1228.52 | 1277.48 | χ2 (4) = 5.83, p = .21 | .043 [.000, .113] | .998 | .009 |

| Satisfaction with Life | ||||||

| Unconditional intercept-only | 2215.07 | 2232.56 | χ2 (4) = 1.50, p = .83 | .000 [.000, .057] | 1.000 | .014 |

| Unconditional linear | 2219.79 | 2247.77 | χ2 (1) = .22, p = .64 | .000 [.000, .132] | 1.000 | .006 |

| Model 1 | 2218.16 | 2242.64 | χ2 (8) = 6.66, p = .57 | .000 [.000, .066] | 1.000 | .019 |

| Model 2 | 2214.56 | 2242.53 | χ2 (10) = 7.04, p = .72 | .000 [.000, .052] | 1.000 | .017 |

| Reintegration Difficulty | ||||||

| Unconditional intercept-only | 1363.22 | 1380.70 | χ2 (4) = 7.00, p = .13 | .055 [.000, .122] | .995 | .055 |

| Unconditional linear | 1362.88 | 1390.86 | χ2 (1) = .66, p = .41 | .000 [.000, .157] | 1.000 | .007 |

| Model 1 | 1357.89 | 1382.37 | χ2 (8) = 7.41, p = .49 | .000 [.000, .071] | 1.000 | .037 |

| Model 2 | 1347.91 | 1375.89 | χ2 (10) = 9.07, p = .53 | .000 [.000, .065] | 1.000 | .033 |

Note. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. AIC = Akaike information criterion. BIC = Bayesian information criterion. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. CFI = comparative fit index. SRMR = root mean square residual. Model 1 includes age and combat experience as covariates. Model 2 includes age, combat experience, and identity disruption as covariates.

After deciding on a functional form, we then created a model including combat exposure and age as covariates (Model 1), and adding identity disruption as a covariate (Model 2). This allowed us to directly compare trajectories for the group of participants who reported identity disruption to the group of participants who did not. We included age as a covariate because identity development is theoretically associated with age, and age was the only demographic variable significantly associated with identity disruption codes in these data. We included combat exposure as a covariate because prior research has suggested this variable is an important predictor of veterans’ mental health outcomes (e.g., Dretsch et al., 2016). A very small proportion of the data was missing for each of the outcomes (a maximum of 5.7% in any of the waves). Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data. Longitudinal analyses were conducted using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

We also conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings regarding the relationship between identity disruption and psychosocial outcomes, and to explore other possible relationships between identity disruption, combat exposure, and psychosocial outcomes. The results of these analyses are reported in Supplemental Material. The first set of analyses used regression to examine the association between identity disruption and each outcome at each individual wave (i.e., at baseline, 3-months, and 6-months). The second set used a system of regression equations to analyze the association between identity disruption and repeated measures of each outcome, accounting for the previous measures of that outcome. The third set involved mediation models to test whether identity disruption mediated the relation between combat exposure and each psychosocial outcome. The final set added an interaction term between identity disruption and combat exposure to the regression-based approach used for the first set of sensitivity analyses.

Results

Qualitative Analysis of Identity Disruption

Forty-nine percent (n = 121) of participants had at least one of four writing samples that was coded with an identity disruption theme. The coding process generated four themes capturing types or dimensions of identity disruption: a) loss of meaning or purpose, b) disconnection between past, present, and future selves, c) role disruption, and d) loss of self-worth. Frequencies, reliability estimates, and degree of co-occurrence of different themes within individuals are reported in Table 2.

Loss of meaning or purpose.

Sixty-seven (27%) participants reported feeling a loss of meaning or purpose after returning from deployment. For many participants, disconnecting from the military left them feeling unfulfilled, questioning the meaning of their work and lives. For example, one participant wrote: “There is nothing in civilian life that will ever be as fulfilling or important as what I did in the military. I have never felt as proud or as special and I will never feel that way again.” This category also included missing the feeling of contributing to a larger mission, or having a positive impact. For instance, another participant stated, “Now I feel lost and I don’t know which way to go. I feel like I’m not of importance or making a difference in my day to day actions. I guess I just feel stagnant.”

Disconnection between past, present, and future selves.

Sixty-seven (27%) participants indicated feelings of disconnection between their past, present, or future selves. Participants whose identity disruption involved disconnection between their past and present selves often expressed feeling cut off or estranged from their past selves, or alternatively, trapped in the past, missing being their past selves, and unable to move forward. For example, one participant wrote:

I try not living in the past but it’s hard to move on from something that you lived for the past 4 years I feel that everyone has moved on and I’m sort of stuck in the past. I wish I could turn back time.

Other participants felt disconnected from their future selves, often expressed as feeling directionless or unable to imagine a viable future. As one participant put it, “About the future, who will I be? I have no clue and that’s the worst of it.”

Role disruption.

Some participants (n = 82, 34%) experienced disruption focused around a specific social role, such as parent, soldier, civilian, woman, mechanic, or athlete. For example, one participant described difficulty switching to the role of parenting after having served in a military leadership role:

One of the frustrating things about transitioning is the loss of power that you feel when coming home from deployment. In Afghanistan I was the executive officer of a transportation company that delivered critical supplies to dozens of different forward operating bases and combat outposts…I was awarded a Bronze Star for my extraordinary success and hard work...Then when I got home, I had to learn to be a dad. My daughter was born while I was gone and my wife and her were in a pretty good routine. So, I come in and get treated like some type of assistant who doesn’t know anything.

Loss of self-worth.

Responses in this category (n = 34 participants, 14%) involved a negative evaluation of the new self. For example, participants experiencing a loss of self-worth often expressed doubts about the value of their past accomplishments, feeling like they had been “demoted” to a less important place in the world, or feeling like their lives had become an embarrassment. As one participant described,

I feel so pathetic right now. I was a strong person, someone who graduated basic training with honors!...I had respect, I had a life, I had friends, I was good at what I did. I could do things for myself. I feel like a bottom feeder right now.

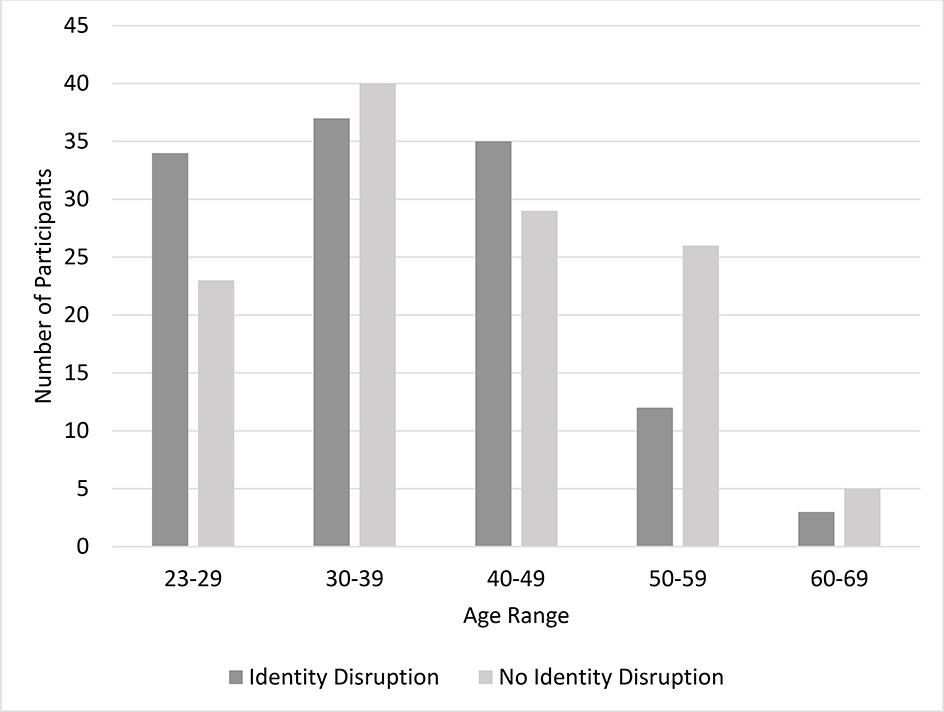

Identity Disruption and Demographics

Chi-square analyses were used to test for associations between identity disruption and the following categorical demographic variables: sex, race, parenthood, marital status, education level, income level, military branch, rank, and component. These tests revealed no deviations from the expected distributions, all ps >.05. Two-tailed, independent samples t-tests were used to compare the average age, number of deployments, and time since last deployment for individuals reporting identity disruption compared to those not reporting identity disruption. There were no significant differences in number of deployments, or in time since last deployment, ps > .05. Only age was significantly associated with identity disruption (see Figure 2). On average, individuals reporting identity disruption were slightly younger (M = 37.31, SD = 10.29) than individuals not reporting identity disruption (M = 40.24, SD = 10.74), t(242) = 2.176, p = .03, d = .28.

Figure 2.

Histogram for Identity Disruption by Age Range.

Identity Disruption and Psychosocial Outcomes

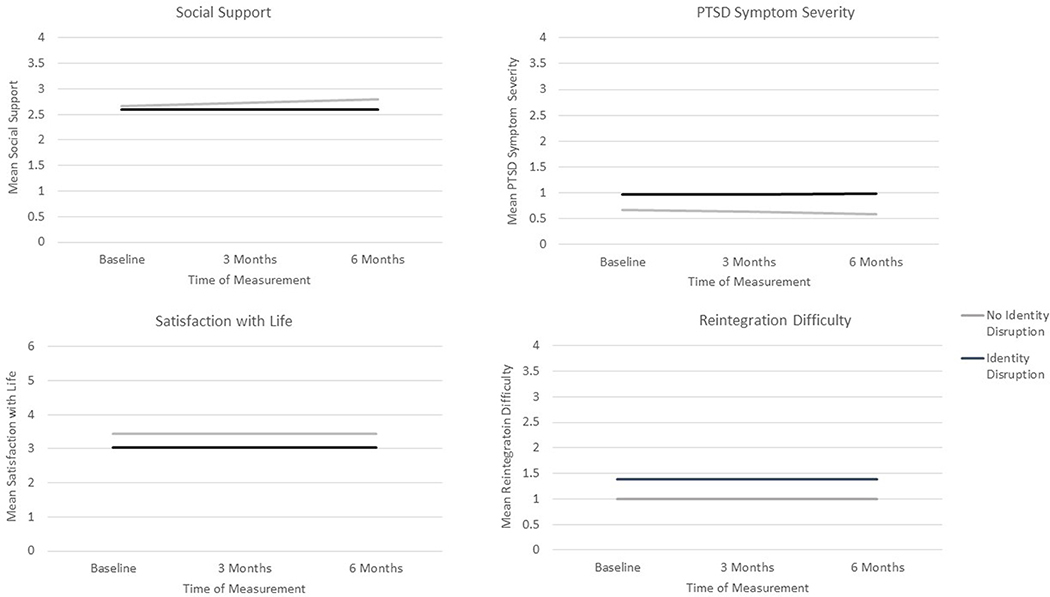

Parameter estimates for Model 1 (with age and combat exposure) and Model 2 (adding identity disruption) are reported in Table 6, and graphs are in Figure 3. Coefficients for the fixed-effect intercepts represent the intercept and slope for individuals with mean age, and no identity disruption or combat exposure. Fixed-effect coefficients for age, combat exposure, and identity disruption represent the change in intercept or slope corresponding with a one-unit increase in each variable.

Table 6.

Parameter Estimates for LGM Estimating Psychosocial Outcomes.

| Social support | PTSD symptoms | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| For intercept | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.62*** | .06 | 2.66*** | .07 | .81*** | .09 | .67*** | .10 |

| Age | −.003 | .004 | −.004 | .004 | .008 | .005 | .01 | .005 |

| Combat exposure | .007 | .01 | .007 | .01 | .10*** | .01 | .10*** | .01 |

| Identity disruption | − | − | −.07 | .08 | − | − | .29** | .11 |

| For slope | ||||||||

| Intercept | .03 | .03 | .07* | .03 | −.01 | .03 | −.04 | .04 |

| Age | −.002 | .002 | −.003 | .002 | .003 | .002 | .003 | .002 |

| Combat exposure | −.007 | .004 | −.007 | .004 | −.003 | .005 | −.003 | .005 |

| Identity disruption | − | − | −.07* | .03 | − | − | .05 | .04 |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | .27*** | .04 | .27*** | .04 | .63*** | .07 | .62*** | .07 |

| Slope | .006 | .02 | .006 | .02 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .02 |

| Satisfaction with life | Reintegration difficulty | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| For intercept | ||||||||

| Intercept | 3.23*** | .14 | 3.44*** | .16 | 1.18*** | .09 | 1.00*** | .10 |

| Age | −.004 | .008 | −.006 | .008 | .008 | .005 | .01* | .005 |

| Combat exposure | −.02 | .02 | −.02 | .02 | .04** | .01 | .04** | .01 |

| Identity disruption | − | − | −.41* | .17 | − | − | .38*** | .11 |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.59*** | .17 | 1.55*** | .16 | .67*** | .07 | .64*** | .06 |

Note.

= p < .001

= p <.01

= p <.05.

Figure 3.

Trajectories for Psychosocial Outcomes, by Identity Disruption.

Note. Trajectories in Figure 3 represent the model-implied trajectories for individuals reporting identity disruption (black line) compared to those not reporting identity disruption (gray line). For the purposes of illustrating associations between identity disruption with each outcome, holding all other predictors equal, all models were evaluated at age = 38.78 (the mean age of the sample), and combat exposure = 0.

Social support.

A linear functional form provided the best fit for the unconditional model (I = 2.65, p <.001; S = −.001, p = .97). On average, participants’ level of social support was rated between “Neither agree nor disagree” and “Somewhat agree,” with very little change over time. Model 1, which included age and combat exposure as covariates, revealed no significant associations. However, in Model 2 there was a significant association between identity disruption and slope, such that participants not reporting identity disruption gradually increased in social support over time (S = .07, p = .03), while participants reporting identity disruption remained stable (S = .001).

PTSD symptoms.

A linear functional form provided the best fit for the unconditional model for PTSD symptoms (I = 1.30, p < .001, S = −.03, p = .16). Participants reported an average PTSD symptom severity, falling between the scale points corresponding to “A little bit” and “Moderate,” with small but nonsignificant decreases over time. Combat exposure and identity disruption were each significantly associated with baseline PTSD symptoms. No significant associations were found with slopes.

Satisfaction with life.

The fit statistics for models of satisfaction with life did not clearly indicate whether an intercept-only or linear model provided better fit, so we ran both sets of models. On average, participants reported satisfaction with life corresponding to the neutral scale point (“Neither agree or disagree”), with slight nonsignificant increases over time (for the intercept-only model, I = 3.14, p < .001; for the linear model, I = 3.10, p < .001; S = .04, p = .27). Including slope in the model did not reveal any significant findings that were not already apparent from the intercept-only models, so for Models 1 and 2 we report the results of the intercept-only models. Neither age nor combat exposure was significantly associated with satisfaction with life; however, those who reported identity disruption tended to report lower life satisfaction at baseline.

Reintegration difficulty.

As with satisfaction with life, the fit statistics for reintegration difficulty did not conclusively point to one functional form over the other. As above, the linear models did not reveal any results that differed substantially from the intercept-only models. The intercept-only unconditional model indicated that participants reported, on average, between “a little difficulty” and “some difficulty” with the reintegration transition, with little change over time (for the intercept-only model, I = 1.37, p < .001; for the linear model, I = 1.37, p < .001, S = −.005, p = .80). Greater combat exposure, age, and identity disruption were each associated with more reintegration difficulty at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses.

Our sensitivity analyses indicated that the results of the above analyses remained largely unchanged when applying different analytic approaches (see Supplemental Material). Levels of social support were similar across the two groups until they diverged at 6-months, with participants who reported identity disruption experiencing slightly lower social support than those who did not. PTSD symptom severity and reintegration difficulty remained consistently higher, and satisfaction with life consistently lower, for those participants who reported identity disruption (see Table S1, Table S2, Figure S1). Identity disruption did not appear to significantly mediate the effects of combat exposure (Figure S2), or interact significantly with combat exposure (Table S3), but rather was associated with psychosocial outcomes independently of combat exposure.

Discussion

This study extended the empirical literature on temporal identity integration in established adulthood and midlife, and operationalized a new construct that captures a loss of temporal integration: identity disruption. Identity disruption, as defined here, captures the discontinuity that adults may experience in the face of a major life event that disrupts their prior identity commitments. Identity disruption was quite common within this sample of adults who ranged in age from 23 to 67, with almost half of participants meeting the coding criteria for identity disruption. The importance of identity disruption was demonstrated by its relationships with psychosocial outcomes. Specifically, veterans reporting identity disruption had more severe PTSD symptoms, lower life satisfaction, and more reintegration difficulty at baseline, and veterans who did not report identity disruption had larger increases in social support over time. This suggests that, although adulthood may be a time of identity stability for most individuals, disruptive life events such as reintegration may introduce discontinuities that can persist over time, and are associated with worse psychosocial outcomes. Overall, our findings demonstrate how identity may become especially salient in the context of adapting to major life changes – a context that is relevant across the lifespan (Brandstadter & Greve, 1994).

Identity Disruption and Adult Identity Development

Though adolescence is the time of life traditionally associated with identity formation (Erikson, 1968; 1950), we found that many veterans in their twenties, thirties, and forties reported identity disruption themes. These decades, which are encompassed by the life stages of established adulthood and midlife, are characterized by deepening one’s commitments in a number of life domains. Key developmental tasks include developing and maintaining close, intimate relationships with others, raising a family, rising to positions of leadership in careers, and maintaining physical health in the face of emerging chronic health concerns (Arnett & Schwab, 2014; Lachman, 2004; Lachman et al., 2015; Mehta et al., 2019).

Returning to civilian life may pose a threat to veterans’ temporal identity integration because it involves major disruptions across several of these domains that are salient in established adulthood and midlife (Sayer et al., 2010). For example, veterans are often physically separated from many of the individuals in the closest ring of their social convoy, i.e., those with whom they interacted on a regular basis during deployment, and with whom they had developed close, trusting relationships (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). Family relationships are often strained in the reintegration process, as veterans and family members adjust to new routines and roles. Veterans may also find themselves returning to careers that feel less satisfying, or having to find completely new jobs at a time of life when most of their peers have substantial career stability. Finally, reintegration may be a time of taking stock of one’s health, and realizing the long-term impacts of any injuries or conditions acquired during deployment.

We expect that many other life transitions can similarly have broad, sweeping effects across many life domains, and may interfere with aspects of identity that the individual perceives as meaningful, stable pieces of their self-definition (Brandstadter & Greve, 1994). For example, events like divorce, job loss, and bereavement may similarly destabilize individuals’ existing identities, and are not uncommon across adulthood. Thus, established adulthood and midlife may be a time when identity commitments made earlier in life are challenged, and individuals must find ways to cope with threats to their identity. Such disruptions may be especially challenging in these phases of adulthood, relative to other times of life. For example, whereas adolescents and emerging adults are afforded a moratorium on major life responsibilities, allowing them to devote substantial time and energy to identity exploration (Arnett, 2000), midlife is typically a time of peak responsibilities (Lachman, 2004) and thus opportunities for identity exploration may be more limited. The present study did not include many participants over age 60, so we hesitate to draw firm conclusions about later-life from this sample, but do note that identity disruption was relatively uncommon among our oldest participants. Future research should examine how the timing and developmental context of disruptive life events might buffer or exacerbate their effects on identity integration across the lifespan.

Identity Disruption Themes

The qualitative coding process revealed several dimensions of identity disruption reported by veterans, including feelings of loss of meaning and purpose; disconnection between one’s past, present, and future selves; role dysfunction; and loss of self-worth. These themes exemplify how identity dynamics in adulthood may differ from those typically associated with adolescence. For example, Marcia’s (1966) identity status model, and subsequent elaborations based on this approach (e.g., Crocetti et al., 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008), focus on the processes of identity exploration and commitment: experimenting with different possible identities, and settling on which components to keep as stable parts of one’s identity. Perhaps these same kinds of exploration and commitment processes are at play for veterans who do not experience reintegration difficulty. However, the way that exploration and commitment are typically conceptualized does not capture the deep sense of loss and disorientation that characterize identity disruption in this sample. A true lifespan model of identity development should be able to explain not only the processes of establishing an identity in adolescence, but also the dynamics involved when an important piece of identity is threatened or lost in adulthood. Identity disruption may thus provide a valuable extension to existing identity models that tend to focus on formation processes.

Linking the specific identity disruption themes we observed to related lifespan developmental trends, it becomes clear that identity disruption as characterized in this study represents a divergence from normative developmental patterns. For example, research on developmental trajectories of purpose in life suggests that mean levels of sense of purpose tend to be relatively stable across the adult lifespan (Hill et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2016). However, longitudinal evidence suggests there is also a subset of individuals who increase or decrease substantially over time (Hill & Weston, 2019). Similarly, mean levels of self-esteem remain fairly stable across the lifespan (Wagner et al., 2013), with modest increases from young adulthood to late mid-life, followed by slight declines through late adulthood (Orth et al., 2010; Orth & Robins, 2014; Wagner et al., 2015). Nonetheless, this overall trend of stability may mask a minority of individuals who experience substantial change in self-esteem. Indeed, longitudinal models of self-esteem indicate significant variability in individual trajectories (Orth et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2013). Our findings suggest that identity disruption may help explain intraindividual variation in sense of purpose, self-esteem, and other identity-relevant constructs, which may drop substantially after a disruptive event such as reintegration.

On its surface, identity disruption may appear to overlap conceptually with derailment, a recently introduced construct describing a change in life direction such that one’s past sense of self is no longer accessible, and is seen as fundamentally different from the present self (Burrow, Hill, Ratner, & Fuller-Rowell, 2020). Although derailment and identity disruption may both represent a lack of temporal identity integration, they are characterized differently in at least three ways. First, derailment focuses on disconnection between past and present selves (Burrow et al., 2020), whereas identity disruption also encompasses disconnection from one’s imagined future self, as reflected in our qualitative findings. Second, identity disruption is explicitly tied to a precipitating disruptive event, whereas derailment is not conceptualized as being linked to an event (and initial validation studies have indeed found that derailment is not associated with status-changing life events; Burrow et al., 2020). Third, identity disruption is conceptualized as a negative, distressing change in identity, whereas derailment is not linked to the valence of the change in self-concept. This difference becomes especially evident when examining items used to measure derailment, such as, “Sometimes I notice how different I am now from who I used to be” and “I feel like I’ve become a different type of person over time.” Derailment, as measured, may encompass adaptive growth and evolution of identity over time, such as becoming more proud of oneself (Burrow & Hill, 2019). Derailment and identity disruption may thus be two related but distinct forms of temporal identity discontinuity, with potentially different consequences for mental health. Given the conceptual differences between them, identity disruption might be expected to be more consistently related to negative mental health outcomes. Future research should examine relations among identity disruption, derailment, and other types of problems in identity integration, and the distinct contributions these constructs may make to well-being.

Relations between Identity Disruption and Psychosocial Outcomes

In addition to exploring qualitative aspects of identity disruption, we quantitatively tested the associations between identity disruption and psychosocial outcomes. As predicted, identity disruption was associated with greater PTSD symptom severity, lower life satisfaction, and greater reintegration difficulty at baseline. While not associated with lower social support at baseline, identity disruption was associated with a lower trajectory of social support over time. Overall, these results suggest that veterans who report identity disruption tend to have poorer psychosocial outcomes than those who do not. This is consistent with prior research linking identity integration with positive adjustment (e.g., Baerger & McAdams, 1999; Benish-Weisman, 2009), and reinforces the construct of identity disruption as a clinically relevant negative manifestation of temporal identity integration. Previous narrative identity research focused on disruptive life events has tended to emphasize those individuals for whom disruptive events serve as turning points in the life story, and present opportunities for personal growth and maturation (Lilgendahl, 2015). The present study examines the “dark” side of temporal integration (Crocetti et al., 2016), describing the implications of persistently struggling to regain a sense of self-continuity after a disruptive experience.

Klimstra and Denissen (2017) have proposed a theoretical framework that aims to explain both how identity affects mental health, and how psychopathology becomes incorporated into one’s identity. Our findings suggest that identity disruption may help explain certain mental health concerns among veterans reintegrating into civilian life after a hazardous deployment, over and above combat exposure. If future research replicates these findings and suggests a causal relationship between identity disruption and health outcomes among those transitioning to civilian life, then efforts to facilitate reintegration should explicitly address veterans’ identity issues. This could be done in the context of reintegration programs or clinical encounters. Mental health clinicians may address the issues that emerged as central identity disruption themes, such as meaning and purpose in life, sense of belonging and status conferred by social roles, and expectations or hopes for the future. These concerns could be evaluated systematically and addressed with identity-focused strategies among veterans who anticipate transitioning or who have recently transitioned to civilian life. For example, veterans may benefit from opportunities to reflect on their provisional identity commitments, engage in identity exploration, and interact with identity agents (Schachter & Marshall, 2010), such as peers who have successfully navigated a similar transition. Our findings suggest that such efforts may have beneficial effects not only for identity adjustment, but also potentially in preventing or reducing symptoms among veterans returning from combat deployments and faced with the challenge of reintegrating into their home communities.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study was limited in several ways. The first set of limitations centers on issues with the identity disruption variable generated through the coding process. Because identity disruption was coded from open-ended, written qualitative responses, there is no way to distinguish those participants who did not experience identity disruption from those who experienced it, but did not write about it in response to the expressive writing prompt. This may have limited our ability to detect effects of identity disruption, as our coded data likely underestimated the number of participants who experienced identity disruption. Future research could avoid this problem by, for instance, interviewing participants explicitly about the consequences of disruptive events for their sense of self. By examining written responses to a relatively open-ended question we were able to identify themes that were salient and thus conceivably important to participants. As such, we identified themes that can inform the content of future data collection strategies.

Another limitation of the present sample is that it likely overemphasizes negativity in veterans’ reintegration experiences. The study only included individuals who reported at least a little difficulty in their reintegration at the time of screening, and thus excluded those who were no longer struggling with perceived reintegration problems. Therefore, although we found that about half the sample fit our criteria for identity disruption, that proportion may be smaller in a more representative sample of veterans.

A third limitation is the long time since deployment for most participants. On average, participants began the study six years after returning from their most recent deployment. In some ways, this facilitated investigation of identity disruption because participants had time to digest their experiences and to observe the long-term consequences of reintegration for their lives and identities. However, it also meant that participants were more distant from military discharge, and may have overcome feelings of disruption that could have existed closer to their return, or might have experienced changes in temporal continuity associated with other major life events since their military discharge. Analyzing longitudinal data collected before, during, and at various time points after a disruptive event (as opposed to only retrospective accounts) would more clearly demonstrate the temporal unfolding of identity disruption and its consequences.

The present study does not provide causal explanations for mental health and social support trajectories. Designs that measure both mental health and identity at several time points are necessary to determine directions of effects (Klimstra & Denissen, 2017). Identity disruption was measured within 10 days after the baseline assessments of mental health, though the disruptive events (e.g., military discharge and reintegration in home communities) described in the writing samples generally happened long before the start of the study. The identity concerns described by veterans generally were perceived as persistent issues that had been ongoing throughout their reintegration transition, not issues that had emerged within the few days between the baseline assessment and expressive writing. The finding of largely stable differences in PTSD symptoms, life satisfaction, and reintegration difficulty over the six months of assessment may reflect the longstanding nature of participants’ identity concerns and relatively stable mental health status by the time of participating in this study. Research conducted closer in time to the disruptive event may reveal more dynamic patterns of change in mental health as a function of identity disruption. Furthermore, the present study was situated within the context of an expressive writing intervention designed to improve mental health (author citation omitted). Therefore, one possible interpretation of the results demonstrating different rates of change (i.e., for social support) is that identity disruption could moderate the effect of the intervention. The longitudinal results of this study should be taken as purely descriptive of the different trajectories evinced by those reporting or not reporting identity disruption, while recognizing that identity disruption may not cause those differences.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that identity disruption is a common experience for veterans who report reintegration problems, and suggests that disruption may be an appropriate construct for studying identity development in adulthood. The findings provide a detailed illustration of what the experience of identity disruption is like for veterans who have undergone the reintegration transition, and demonstrate the associations between identity disruption and social support, PTSD symptoms, life satisfaction, and reintegration difficulty. By taking advantage of existing rich, high-quality data from an intervention trial, this secondary analysis has opened the door for much needed research on identity dynamics in adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. DoD (Grant 08-2-0045) and Department of VA, HSR&D (Grant DHI-07-150). The authors thank Dr. Moin Syed for feedback on study design and earlier versions of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lauren L. Mitchell, Center for Care Delivery & Outcomes Research, Minneapolis VA Health Care System

Patricia A. Frazier, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota

Nina A. Sayer, Center for Care Delivery & Outcomes Research, Minneapolis VA Health Care System & Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry, University of Minnesota

References

- Abreu RL, Riggle ED, & Rostosky SS (2019). Expressive writing intervention with Cuban-American and Puerto Rican parents of LGBTQ individuals. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 106–134. doi:0011000019853240. [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM (2012). Living into the story: Agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 367–389. doi. 10.1037/a0025289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, & Schwab J (2014). The Clark University poll of emerging adults ages 25–39 becoming established adults: Busy, joyful, stressed — And still dreaming big. Retrieved from https://www2.clarku.edu/clark-poll-emerging-adults/pdfs/Clark_Poll_2014_Hires_web.pdf

- Baddeley JL, & Pennebaker JW (2011). A postdeployment expressive writing intervention for military couples: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24, 581–585. doi: 10.1002/jts.20679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley J, & Singer J (2010). A loss in the family: Silence, memory, and narrative identity after bereavement. Memory, 18(2), 198–207. doi: 10.1080/09658210903143858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerger DR, & McAdams DP (1999). Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well-being. Narrative Inquiry, 9(1), 69–96. doi. 10.1075/ni.9.1.05bae [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer JJ, & McAdams DP (2004). Personal growth in adults’ stories of life transitions. Journal of Personality, 72(3), 573–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Vignoles V, Owe E, Easterbrook M, Brown R, Smith PB, … Lay S (2018). Being oneself through time: Bases of self-continuity across 55 cultures. Self and Identity, 12(3), 276–293. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1330222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benish-Weisman M (2009). Between trauma and redemption: Story form differences in immigrant narratives of successful and nonsuccessful immigration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(6), 953–968. doi. 10.1177/0022022109346956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, & Greve W (1994). The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review, 14(1), 52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, & Hill PL (2019, October). Paradise lost and found: Sense of purpose attenuates links between derailment and distress. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for the Study of Human Development, Portland, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, Hill PL, Ratner K, & Fuller-Rowell TE (2020). Derailment: Conceptualization, measurement, and adjustment correlates of perceived change in self and direction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 584–601. doi. 10.1037/pspp0000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson J, Wängqvist M, & Frisén A (2015). Identity development in the late twenties: A never ending story. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Nation A, Gómez W, Sundberg J, Dilworth SE, Johnson MO, … & Rose CD (2015). Pilot trial of an expressive writing intervention with HIV-positive methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo A, Martínez-Sanchis M, Etchemendy E, & Baños RM (2019). Qualitative analysis of the Best Possible Self intervention: Underlying mechanisms that influence its efficacy. PloS One, 14(5). doi. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE, Sokol BW, & Hallett D (2003). Personal persistence, identity development, and suicide: A study of Native and Non-native North American adolescents. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 68(2), 1–130. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Beyers W, & Çok F (2016). Shedding light on the dark side of identity: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 104–108. doi. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Rubini M, & Meeus W (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 207–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers A (2011). When veterans return: The role of community in reintegration. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(2), 160–179. 10.1080/15325024.2010.519281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dey I (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative research. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dretsch MN, Williams K, Emmerich T, Crynen G, Ait-Ghezala G, Chaytow H, … & Iverson GL (2016). Brain-derived neurotropic factor polymorphisms, traumatic stress, mild traumatic brain injury, and combat exposure contribute to postdeployment traumatic stress. Brain and Behavior, 6(1). doi. 10.1002/brb3.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E (1946). Ego development and historical change. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2(1), 359–396. doi. 10.1080/00797308.1946.11823553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton [Google Scholar]

- Frees EW (2004). Longitudinal and panel data: Analysis and applications in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, & Kober C (2015). Autobiographical reasoning in life narratives buffers the effect of biographical disruptions on the sense of self-continuity. Memory, 23(5), 664–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Turiano NA, Spiro A III, & Mroczek DK (2015). Understanding inter-individual variability in purpose: Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, & Weston SJ (2019). Evaluating eight-year trajectories for sense of purpose in the health and retirement study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(2), 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, & Mullen M (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). Returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary assessment of readjustment needs of veterans, service members, and their families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, & Antonucci TC (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In Baltes PB & Brim O (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 254–283). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling M (2018). Stories of transition: US Veterans’ narratives of transition to civilian life and the important role of identity. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 4(2), 28–36. doi. 10.3138/jmvfh.2017-0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, King LA, & Vogt DS (2003). Manual for the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI): A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military veterans. Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD. doi: 10.1207/s15327876mp1802_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King L, & Raspin C (2004). Lost and found possible selves, subjective well-being, and ego development in divorced women. Journal of Personality, 72(3), 603–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, & Denissen JJ (2017). A theoretical framework for the associations between identity and psychopathology. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2052. 10.1037/dev0000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HJ, Hooker K, Geldhof GJ, & McAdams DP (2016). Longitudinal purpose in life trajectories: Examining predictors in late midlife. Psychology and Aging, 31(7), 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J (2015). Identity development through adulthood: The move toward “wholeness.” In McLean KC & Syed M (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 65–95). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199936564.013.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 305–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Teshale S, & Agrigoroaei S (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilgendahl JP (2015). The dynamic role of identity processes in personality development: Theories, patterns, and new directions. In McLean KC & Syed M (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of identity development (p. 490–507). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Schwartz SJ, Berzonsky MD, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Smits I, & Goossens L (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 58–82. doi. 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (1966). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar]