Abstract

There is a widespread belief that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased global income inequality, reducing per capita incomes by more in poor countries than in rich. This supposition is reasonable but false. Rich countries have experienced more deaths per head than have poor countries, their better health systems, higher incomes, more capable governments and better preparedness notwithstanding. The US did worse than some rich countries but better than several others. Countries with more deaths saw larger declines in GDP per capita. At least after the fact, fewer deaths meant more income. As a result, per capita incomes fell by more in higher-income countries. Country by country, international income inequality decreased. When countries are weighted by population, international income inequality increased, in line with the original intuition. This was largely because Indian GDP fell and because the disequalizing effect of declining Indian incomes was not offset by rising incomes in China, which is no longer a globally poor country. That these findings are a result of the pandemic is supported by comparing global inequality using IMF forecasts in October 2019 and October 2020. These results concern GDP per capita and say little or nothing about the global distribution of living standards, let alone about the global distribution of suffering during the first year of the pandemic.

0. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has threatened the lives and livelihoods of the less-educated and less-well paid more than those of more educated and better paid, many of whom can stay safely at home and continue to work. To a lesser or greater extent, the increase in domestic income inequality has been offset by large scale government income support programs in the US and in many other countries.

International income inequality is another matter, and there is a widespread belief that the pandemic has or will increase inequalities in income between countries. In one of many such examples, Goldin and Muggah,(1) writing for the World Economic Forum, say ‘inequality is increasing both within and between countries’. The United Nations Development Program writes, ‘The virus is ruthlessly exposing the gaps between the haves and the have nots, both within and between countries’.(2) Stiglitz(3) lays out the rationale: ‘COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated inequalities between countries just as it has within countries. The least developed economies have poorer health conditions, health systems that are less prepared to deal with the pandemic, and people living in conditions that make them more vulnerable to contagion, and they simply do not have the resources that advanced economies have to respond to the economic aftermath”.

This argument seems compelling, but it is good to check the data. I demonstrate that global inequality—defined as the dispersion of per capita GDP between countries taking each country as a unit—has continued on its pre-pandemic downward trend and has, if anything, fallen faster as a result of the pandemic. This finding is fragile, is sensitive to outcomes in small economies, and bears little relationship to what we might reasonably care about, which is international inequality in material living standards. It may also be temporary; indeed, the managing director of the IMF warned in February 2021 that ‘There is a major risk that as advanced economies and a few emerging markets recover faster, most developing countries will languish for years to come’.(4) Much will depend on how vaccines are rolled out.

An alternative to measuring global inequality country by country is to weight each country by its population, and by this measure, between-country income inequality has increased, largely because of India’s poor performance during 2020. The rise in this kind of global income inequality is in line with the intuitive notion of poor countries suffering the largest income loss. China did well, but China is today no longer a globally poor country, so that its exceptionally positive outcome during the pandemic had little effect on global income inequality. The rapid growth of China has, for decades, decreased population-weighted between-country inequality, because it has lifted more than one billion people up from the bottom of the world income distribution. But because China is now in the middle of the global distribution of country incomes, this effect has run its course.

For reasons that are only partially understood, and which may include greater undercounts in poorer places, poorer countries suffered fewer COVID deaths per capita in 2020 than did richer countries. At the same time, each country’s loss in per capita national income between 2019 and 2020 was strongly related to its per capita COVID death count. These two facts together meant that over the course of the pandemic up to the end of 2020, per capita incomes have, on average, fallen more in countries with higher per capita GDP in 2019; the 97 poorest countries lost an average of 5% of their 2019 per capita GDP, while the 96 richest countries, with an average per capita income six and a quarter times larger, lost an average of 10%. This need not have narrowed international income inequality, but it did. Country by country, with tiny countries counting the same as giant countries, per capita incomes were closer to one another in 2020 than in 2019.

China (unlike India) had few deaths and experienced positive economic growth in 2020. Before the pandemic, China’s rapid growth had lifted more than a billion people up from the bottom of the global income distribution, and this growth has long been responsible for a reduction in global income inequality when each country is weighted by its population. But this effect has attenuated as China’s income has risen. Today, out of the world’s population of 7.8 billion, 4.4 billion live in countries whose per capita income is lower than China, while only 2.0 billion live in countries whose per capita income is higher than China. During the pandemic, the Chinese economy grew while most other economies shrank, but this did not have much effect on global inequality, so that with the Indian economy shrinking, population-weighted global inequality increased.

Contrary to pre-existing trends, the pandemic reduced global unweighted inequality and increased global population-weighted inequality. That my findings are consequences of the pandemic is supported by comparing inequality measures using IMF income estimates pre- and post-pandemic.

It is important to be clear about what I am and am not claiming here. My results say nothing about whether the degree of suffering has been larger or smaller in poor countries; in particular, they are consistent with the pandemic increasing poverty around the world and do not contradict the World Bank’s estimates that between 88 and 115 million people will be pushed into poverty.(5) Even if all countries had the same decline in per capita income, the poorer countries would have had larger increases in poverty because they have many more people near the global poverty line. As it is, we know from Decerf and colleagues(6) that, compared with richer countries, the suffering from the pandemic has hit poor countries more in terms of poverty and less in terms of mortality. All of my results come from national accounts data, and there is a long history of national accounts data on consumption and income differing from consumption and income as recorded in the household survey data that are used for the assessment of poverty and within-country inequality. Beyond that, GDP per capita is often a poor indicator of material living standards if only because GDP contains much—such as profits accruing to foreigners—that are close to irrelevant for domestic consumption, even as measured in the national accounts.

My findings may be temporary. The pandemic is not done, there are more deaths to come, and they may fall more heavily on poorer countries. Indeed, given that the pandemic started along trade routes and affected urban before rural areas, it is plausible that current patterns will change once more. It is also possible that deaths are severely understated in poor countries, some of whom do not have regular vital statistics systems that comprehensively report deaths even in normal times. My calculations use data up to the end of 2020, before vaccines had any chance to affect outcomes, and they say nothing about the how vaccines will be distributed between countries. Vaccines are reaching rich countries first, and it is entirely plausible that rich countries will recover more rapidly in 2021 and beyond, which will widen global inequalities.

My results concern two distinct measures of international income inequality: the dispersion of per capita income between countries, with each country as a unit of observation, and the dispersion of per capita income between countries, but where each country is weighted by population. Milanovic(7) has usefully labeled these inequality measures as Concept 1 and Concept 2 respectively. Concept 1 treats each country as an individual and calculates inequality between those ‘individuals’. Concept 2 pretends that each person in the world has their country’s per capita income and then calculates inequality among all these persons. Both Concept 1 and Concept 2 are between country measures and both ignore within country inequality. The distribution of income between all persons in the world, which Milanovic calls Concept 3 inequality, starts from Concept 2 but then adds in the distribution of income within countries, which is also changing because of the pandemic and the policy responses to it. Because between country inequalities in per capita income are larger than within country income inequalities, changes in Concept 2 inequality are often a good guide to changes in Concept 3 inequality.

It is entirely possible for the global distribution of income among all persons in the world to have widened while one or both of the between country measures have been decreasing. Over the last 30 years, largely because of the rapid growth in per capita incomes in India and China, population-weighted between-country inequality (Concept 2) has fallen, while unweighted inequality (Concept 1), which rose until around 2000, has fallen since then.(8) At the same time, before the pandemic, the fall in weighted between-country inequality has been accompanied by rising inequality within many countries, with the net effect that the global distribution of income between all the people in the world has become more equal.(8,9 p262). But the enrichment of China has diminished the size of the contribution that its high growth (and large population) has made to narrowing the global distribution of income among all persons; if a country grows fast enough for long enough, it will inevitably become rich.

1. Income, Income Growth, and Deaths from COVID-19

I use data on total deaths per million from Our World in Data as of December 31, 2020. Data on real national income per capita, expressed in 2017 international (PPP) dollars are taken from the IMF World Economic Outlook of October 2020,(10) from the World Bank’s Global Economic Outlook of January 2021,(11), and from its World Development Indicators database. The IMF data, which is my main source, covers 193 countries; income data are missing for Syria and Somalia.

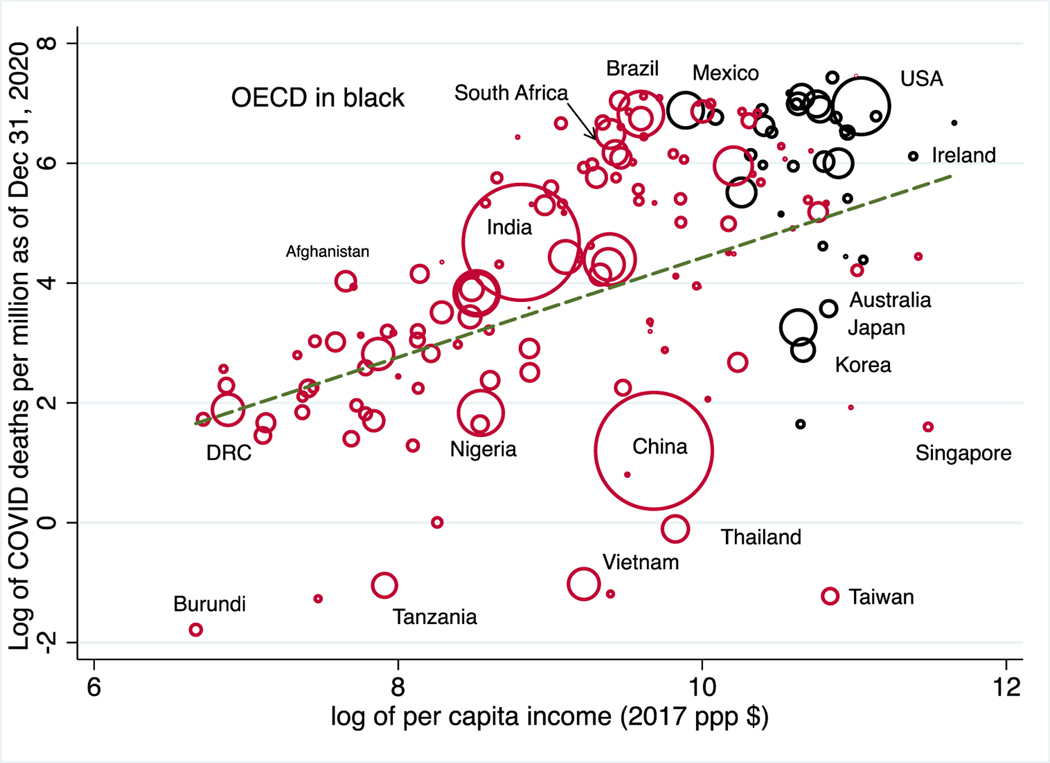

Figure 1 shows the scatterplot across countries of the logarithm of deaths per million against the logarithm of income per head in 2019; there are 169 countries with non-missing values of both variables. The areas of the circles are proportional to population. The circles are shown in black for the OECD countries and in red for the countries not in the OECD. The population-weighted regression line is shown as the dashed line; its slope is 0.83 (t=4.9). The unweighted regression line is somewhat steeper, 0.99 (8.6).

Figure 1:

COVID-19 deaths per million and per capita income in 2019. Broken line is the population-weighted regression line, areas of circles proportional to population. OECD countries shown in black.

There is no relationship between per capita income and COVID deaths per million within the OECD, weighted or unweighted, so the positive relationship is dominated by the relationship between OECD and non-OECD countries, as well as by the relationship within the non-OECD itself. Among the latter, much depends on India and China. Ignoring population size, the country-by-country relationship in the non-OECD is close to that for all countries. Weighted by population size, the relation also exists within the non-OECD if China is excluded; China’s low death toll is an outlier, and its population is the largest in the world, so its inclusion annuls the relationship.

My main purpose here is measurement, but the positive relationship in Figure 1, previously documented by Goldberg and Reed,(12,13) raises important issues, if only because it contradicts so many pre-suppositions. Studies of global health and global income, ever since Preston’s famous 1975 paper,(14) have universally found that higher income countries have better health. They have better public and private health systems, both of which are expensive, and they usually have governments that are more effective at protecting their population’s health. Such is the basis for Stiglitz’s argument that I quoted in the introduction.(3) More formally, there is a comprehensive 2019 study of global health security by Johns Hopkins, the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Economist Intelligence Unit. That study published a set of global health indexes for 195 countries based on 140 questions that measure country capacity in six dimensions: (i) prevention of the emergence and release of pathogens; (ii) early detection and reporting for pandemics of potential international concern; (iii) rapid response and mitigation of the spread of a pandemic; (iv) sufficiency and robustness of the health system to treat the sick and protect health workers; (v) commitments to improving national capacity, financing, and adherence to norms; and (vi) risk environment and vulnerability to biological threats. These are presented separately, and also aggregated into an overall index.(15 p6).

In line with the ‘health is wealth’ presupposition, the overall index correlates 0.65 with the logarithm of purchasing power parity per capita income over 166 countries; for correlation coefficients between the logarithm of per capita income and the first four indexes listed above are 0.62, 0.48, 0.48, and 0.64. The indexes are also positively correlated with deaths per million, 0.47 for the overall index, and 0.47, 0.41, 0.31, and 0.48 for the first four subindexes. Counter-intuitively, and in spite of being designed to be helpful for ‘high consequence pandemic threats, such as a fast-spreading respiratory disease agent that could have a geographic scope, severity, or societal impact and could overwhelm national or international capacity to manage it’, (15 p7), and in spite of the evident care and thoroughness of the report, countries that did better on the indexes experienced more deaths than those that did worse. It seems that even distinguished and careful experts could not predict the international patterns of deaths in the pandemic, at least through to the end of 2020, neither is it clear that any country could have been adequately prepared for what happened. As countries learn lessons from the pandemic, and try to better prepare for the future, they will presumably have to take measures of which at least some will have to be different from those proposed in the GHS report. Exactly which remains unclear, and more generally, it remains frustratingly difficult to draw policy conclusions from the pandemic so far.

Figure 1 shows the small number of deaths in China, as well as in other East Asian countries, whether in the OECD or not. The very low numbers of deaths in Burundi and Tanzania are most likely due to undercounts; Tanzania stopped reporting cases in May, claiming that it had conquered the virus, while both it and Burundi have rejected offers of vaccines.(16)

Misreporting aside, the low number of deaths in poor countries has been linked by Goldberg and Reed(12,13) to obesity,(17) to the fraction of the population over 70, and to the density of population in the largest urban center. Heuveline and Tzen(18) provide age-adjusted mortality rates for each country by using country age-structures to predict what deaths would have been if the age-specific COVID-19 death rates had been those of the United States; the ratio of predicted deaths to actual deaths is then used to adjust each country’s crude mortality rate. This procedure scales up mortality rates for countries that are younger than the US (Peru has the largest age and sex adjusted mortality rate) and scales down mortality rates for countries like Italy and Spain (which had the highest unadjusted mortality rate) that are older than the US. If Figure 1 is redrawn using the adjusted rates, the positive regression slope remains, although the (unweighted) slope is reduced by a half, from 0.99 to 0.47 (t=4.7); from this, we might conclude that their older age structures explain about half of why richer countries have had more deaths in relation to their populations. In poor countries, many children suffer from ill-health—diarrheal disease, respiratory infections, undernutrition—that could raise the risk of death conditional on infection, which would offset the benefit of their younger age structures.

Poor countries are also warmer countries, where much activity takes place outside, and in some regions, there are relatively few large dense cities with elevators and mass transit, while ultraviolet radiation may directly inhibit the spread of the virus.(19) It is also possible that Africa’s longstanding experience with infectious epidemics stood it in good stead during this one; cross-immunity from other past infections may also help.(20) Countries with more developed economies have a higher fraction of services, many of which involve personal contact. But such ex post stories are worth little without more serious analysis, and again, the serious and thorough analysis in the GHS index report predicted just the opposite.

Perhaps the most surprising result in the figure is the relatively high number of deaths among the highest-income countries. There has been much (warranted) condemnation of the Trump administration’s handling of the epidemic, but deaths per million in the US are no higher than in several other rich countries and not much worse than that predicted from the global pattern. Statements about the disproportionate relationship between deaths and population in America (such as that the US has only 4% of the world’s population but 20% of the deaths, or that the US has more than 30 times as many deaths as Pakistan) are consequences of the pattern in the figure, including the small number of deaths in China, the largest country in the world, and tell us little about how well or badly the pandemic was handled in the US or elsewhere. Deaths in the US are above the regression line of logarithm of deaths per million on the logarithm of income per capita, but by that measure the US did about as well as Sweden, and better than Hungary, Spain, Poland, Portugal, Italy, the United Kingdom, and France. (Belgium is the worst of all, likely partly because of its more comprehensive measure of COVID-19 deaths.) Troesken(21) argues that the US has long been prone to infectious disease; in 1900, after a safe and effective vaccine had been available for more than a century, and in spite of already being the world’s richest country, the US did worse than other rich countries in preventing smallpox deaths. Troesken argues that this was ‘not despite being rich and free, but precisely because it was rich and free’.(21 p176)

For my purposes here, there is no need to try to establish causes. Large scale misreporting is another matter, and again I note that, even with perfect reporting, the dynamics of the pandemic will almost certainly change these patterns in future years.

The second part of the story is the relationship between pandemic deaths and growth in per capita GDP in 2020. Here, I rely on forecast data, of which two sets are available, one from the IMF in October 2020,(22) and one from the World Bank in early 2021.(11) I use the earlier IMF numbers here; the World Bank numbers are close, and the cross-country correlations between the two sets of estimates is 0.945. An obvious concern is that the Bank and the Fund used the death counts to forecast the change in income. But forecasts constructed in October and in January have preliminary first half data for many countries, and we should also worry if data on the pandemic were not incorporated into the forecasts. Again, the most serious concern is about misreporting and about bad GDP forecasts that are based on bad data on deaths. Even so, it will be good to check the results in Figure 2 against the actual growth numbers when they are available.

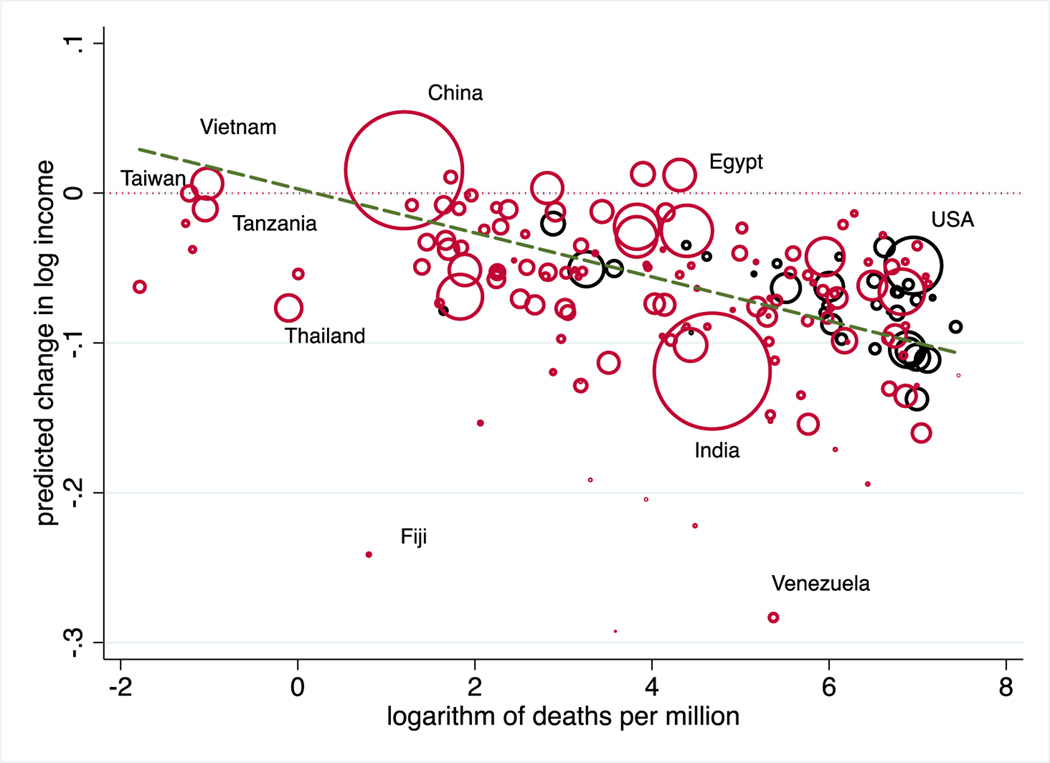

Figure 2:

Predicted growth of per capita income 2019–20 and deaths per million. Population weighted regression shown as broken line, areas of circles proportional to population. OECD countries shown in black.

Figure 2 shows the IMF’s predicted growth rates from 2019 to 2020 plotted against deaths per million. China, with few deaths, shows positive predicted growth; the US, with many deaths, shows negative predicted growth. There are many cases that deviate from the line, with at least some of these deviations having nothing to do with COVID-19, but, as would be expected, the regression slopes are similar for countries in and out of the OECD. The (weighted) regression—shown as the dotted line—has a slope of –0.015 (t=10.2), so that predicted growth decreases by one and a half percentage points for every unit increase in the logarithm of deaths per million; the slope of the weighted regression is –0.007 (t=4.0), about half as much. (I have excluded Libya and Guyana from the figure and the calculations; neither is exceptional in deaths, but Libya has a predicted log change of per capita income of –1.1 and Guyana a predicted log change of +0.23, numbers that are not only (absolutely) very large but presumably unrelated to the pandemic. I have also repeated these calculations using not growth forecast for 2020 in October 2020 but the revision to the 2019 to 2020 growth forecast between the 2019 and 2020 editions of the World Economic Outlook, the idea being to isolate the reduction in growth associated with the pandemic. The corresponding figure and regression results are similar to the originals, albeit with lower levels of predicted growth, so that, for example, all revisions to growth are negative.

It is perhaps not surprising that deaths from COVID-19 should bring economic destruction or that the relationship should be tighter than the relationship between deaths and the previous year’s income. But, once again, that there should be this relationship was not obvious before the pandemic. Indeed, in the early days, there was much discussion of the value of life and about a supposed trade-off between deaths and income, premised on the expectation that lockdowns would save lives but destroy economies. As previously noted by Wolf,(23) who looked at the advanced countries plus India and China, there is no evidence in these cross-country data for the existence of any such trade-off. Instead, the route to growth lies through preventing deaths. These outcomes are what might be expected in the absence of any policy—an unstoppable disease lays waste to both people and economic activity. What governments ought to have done is still remarkably difficult to discern. Infection rates certainly fell during lockdowns, but lockdowns came alongside voluntary social distancing in the face of infection and death and were sometimes as or more important.(10,24) Beyond that, the fluctuations in infection rates have repeatedly defied prediction, so that it is currently not possible to construct good counterfactuals to evaluate the effects of policy.

Figure 3 closes the circle. It plots the income changes from Figure 2 against the 2019 levels of income in Figure 1; it shows that richer countries had slower (or more negative) growth in 2020 than did poorer countries. The slope of the unweighted regression line in the Figure is –0.010 (t=3.3), so that every unit increase in log income shaves one percentage point off of the predicted growth rate. Given the contrasting experiences of the two giants, India and China, the weighted regression has an insignificant small slope of –0.003 (t=0.8). China is growing because, in spite of its relatively high income, it has seen few deaths, while India, with more deaths per million than other countries at its income level, shows a 10.2 percent decline in income. Each country is an outlier but in opposite directions. When I run the same (unweighted) regression using the 2019 predicted growth rates as calculated by the IMF before the pandemic, the slope is still negative but small and insignificant –0.001 (t=1.4).

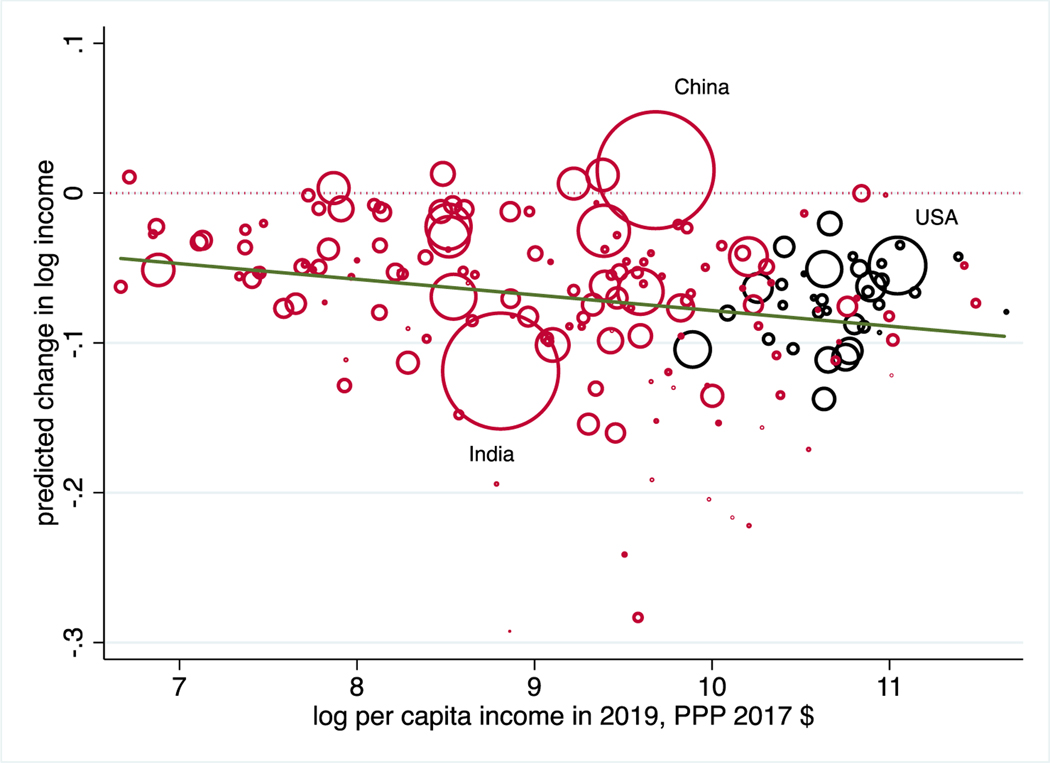

Figure 3:

Growth of per capita income, 2019–20, and per capita income in 2019. Line is unweighted regression line, areas of circles proportional to population. OECD shown in black.

Ignoring population size, the negative relationship between growth in 2020 and income in 2019 exists for the world as a whole and within the non-OECD countries. Within the OECD, the better off countries grew faster in 2020, but the regression coefficient is not significantly different from zero, as can be seen in Figure 3.

That higher income countries experience the largest decreases in income on average does not, in and of itself, imply that there was a decrease in inequality in per capita incomes between countries; the relationship in Figure 3 is not exact, and deviations from the line also affect inequality.

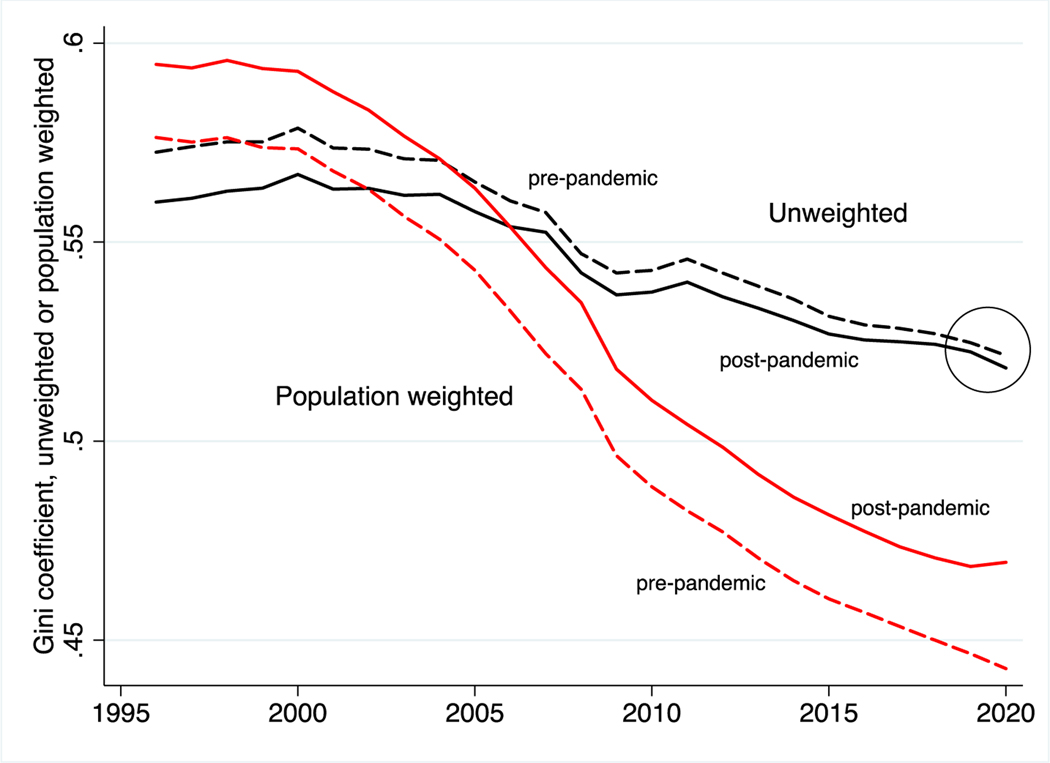

Figure 4 shows estimates of between-country income inequality using the Gini coefficient—a standard measure of inequality that is 0 at complete equality when every unit has the same and 1 at complete inequality when one unit has everything—with and without population weights, all taken from the IMF data. The broken lines are taken from the IMF’s October 2019 World Economic Outlook,(22) which also has predictions of GDP for 2020 but prepared before the pandemic and indeed before COVID-19 existed. The broken and solid lines differ, not only by vintage of data, but also because in 2020 the IMF data moved to 2017 purchasing power parity exchange rates; compared with the previous (2011) round of PPPs, the new figures make the world somewhat more equal without population weights (Concept 1) and rather more unequal with population weights (Concept 2). (PPP exchange rates are exchange rates that adjust for the different price levels in different countries, particularly for lower prices in poorer countries. The International Comparison Program revises these rates every six years or so, and the latest revision, for 2017, was recently incorporated into the IMF and World Bank data.)

Figure 4:

Gini coefficients of income per capita, unweighted, weighted by population. Broken lines use pre-pandemic data

The top lines, marked ‘unweighted’, show the Gini coefficient of national per capita incomes, adjusted for purchasing power, with no account taken of population (Concept 1). In this calculation, each country counts as a unit, no matter what its size, and inequality is calculated as if each country were a person. This measure has a slight upward trend until its peak in 2000 and subsequently declined except during 2008–2011 after the Great Recession. It declined slightly faster (0.004) from 2019 to 2020 than from 2018 to 2019 (0.002). The broken line, my proxy for world inequality in 2020 without the pandemic, has a small decline from 2019 to 2020 (0.003) but less than the actual outcome; the difference between it and the solid line, circled in Figure 4, is the effect of the pandemic. These top lines for Concept 1 inequality, which are the simplest way of examining whether countries are being driven apart by the pandemic, show no widening and, if anything, show a decline.

The bottom line, marked ‘population weighted’, is the Gini of national income per capita, adjusted for purchasing power—all as in the top line—but with each country weighted by its population. This is Concept 2, the measure of inequality for the world where each person in the world is assigned the per capita income of the country in which they live. This measure has been falling for many years, largely because the world’s two largest countries, China and India, have grown rapidly, bringing more than two billion of the world’s population up from near the bottom of the global income distribution to near its middle, where we can see them today in Figures 1 and 3.

This population weighted measure of global inequality rose very slightly between 2019 and 2020, in accord with the story that the pandemic has driven countries apart. Again, the counterfactual is supplied by the broken line from the 2019 forecasts. That the effect can be attributed to the pandemic can be seen from the fact that the pre-pandemic forecast has no such upward tick. This outcome can be largely attributed to India’s poor performance; if Concept 2 inequality is recalculated without India, the uptick is eliminated. By contrast, eliminating China, which did well in 2020, while reducing the level of global inequality, does nothing to eliminate the uptick in 2020. As we have seen, China is in the middle of the world income distribution, where its relative growth performance has little effect on measured inequality.

On the inequality measures themselves, I have repeated the calculations in Figure 4 using two other standard inequality measures, the Theil index and the coefficient of variation. The patterns are the same as shown and described. But that is not true for the standard deviation of logarithms; Figure 4 redrawn with this measure also shows a pandemic-related decline in unweighted inequality and an increase in pandemic-related weighted inequality, but it misidentifies China as the cause of the latter, not India. It is also misleading for the case of Macao, which I discuss below. This sensitivity to the choice of measure might indicate there are no robust conclusions, but it is also true that the variance of logs is a poor inequality measure that can be seriously misleading, even to the extent of increasing in situations where there has been a clear redistribution from rich to poor.(25) The three measures discussed above—the Gini, the Theil, and the coefficient of variation—cannot have perverse results like this, and are to be preferred, and they all give the same qualitative results. I return to Macao below.

2. Conclusions, Lessons, and Reservations

The pandemic has made (most) countries worse off, and there has almost certainly been an increase in global poverty. But that implies nothing about global inequality.

Per capita income losses were generally larger for the countries that were better off in 2019, in part because they saw more deaths per unit of population and in part because of other pandemic related harms. This has not driven countries further apart; instead, the pre-existing downward trend in global inequality continued into 2020 and actually fell somewhat faster. When countries are weighted by their population, there was a slight increase in inequality in 2020, largely because of the decline in per capita incomes in India, without which the previously established downward trend would have continued. The exceptionally positive experience of China had little effect on the measures because of China’s current position in the middle of the world income distribution. For many years in the past, rapid growth in China reduced global inequality because it brought so many people up from the bottom of the distribution. That effect has now worn off, and if, in future, China continues to grow more rapidly than average, it will increasingly cause an increase in global inequality.

Calculations of global inequality raise important methodological issues, some of which are sharply illustrated here. Both concepts of inequality—unweighted on a country-by-country basis, Concept 1, or population weighted, Concept 2—raise uncomfortable issues. The unweighted measure, which is perhaps closest to the lay notion of global income inequality, is sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of small countries. The population weighted measure does not have this drawback, because small countries get little weight, but will instead often critically depend on what happens with India and China, as is the case here. In the pandemic, China, which is relatively well-off, did much better than the rich countries and much better than India, which is poorer than China and which did much worse than the rich countries. Indeed, given the facts in the previous sentence, not much is added by looking at measures of global income inequality. This is more generally true for Concept 2 inequality, which will often just be a more complicated way of telling the story of what has happened to India, China, and the large countries in the OECD.

The presence or absence of small countries matters for the unweighted measures. The two richest countries in 2019, measured by per capita income in 2017 international dollars, were Macao and Luxemburg, with populations of 670,000 and 614,000 respectively. After that, in positions 3 through 8, are Singapore (5.7 million), Qatar (2.8 million), Ireland (4.9 million), Switzerland (8.5 million), Norway (5.4 million), and then the US (328 million). During the pandemic, the IMF predicted that Macao would lose just over one half of its per capita GDP, not because of a large number of COVID-19 deaths, but because the gambling, entertainment and tourism on which it depends were hit by the pandemic. This knocked Macao from first to ninth in the global per capita income rankings and had a large effect on unweighted global inequality; indeed, the unweighted Gini coefficient rises from 2019 to 2020 if Macao is excluded, largely because, without it, the world was more equal in 2019.

One reaction to these findings would be to exclude countries like Macao, if indeed it is a country at all. But it is difficult to do this in a principled way; should the cut-off be one million people, or five million? Another reaction would be to ignore the unweighted measures and focus on the weighted measures. But, as we have seen, they have their own difficulties in that they can simply be a (less insightful) retelling of the India and China story.

Yet the smallness of the very richest countries is far from their worst problem, which is that their GDPs are an exceptionally poor measure of the material wellbeing of their inhabitants. In 2019, the share of household consumption expenditure in GDP was 25.4% in Macao, 29.5% in Luxemburg, 24.5% in Qatar, and 30.4% in Ireland compared with 67.9% in the US. Many of these countries are tax havens, and much of their GDP is profit, including profit accruing to non-citizens, so that when we include these countries in global comparisons, we are not comparing like with like and including much that is unrelated to material living standards of their citizens.(26) Consumption expenditures would be better—though it would not solve the small country problem—but no such numbers are currently available for 2020. And while several arguments can be mounted for excluding Macao, there would be a good deal more discomfort if we were to exclude Singapore or Ireland.

In thinking about policy, the issues with GDP are perhaps the most important lessons from this paper. Shortcomings of GDP are well-known—it misses much that is important, it includes a lot that is not, it ignores distributional issues, and it takes no account of the destruction of the planet—but it remains hard to see how policy makers would manage without it, especially in the short term. But globalization and footloose capital has driven an increasingly large gap between GDP and any useful measure of material wellbeing. Policymakers would do well to refocus on other measures within the GDP stable—such as Actual Individual Consumption—and would be well-served if it were possible to produce those data more rapidly so that real time decisions could turn away from the GDP numbers that are currently made available most rapidly. One example comes from global poverty measurement, where, in the absence of survey data in the short term or during crises like the present pandemic, the World Bank uses growth in GDP to assess likely changes in household consumption and thus in poverty.

On the pandemic itself, and on policies to contain it, my analysis has little to contribute. We do not know why poorer countries had fewer deaths, neither do we understand the dynamics of infection, beyond the obvious fact that social distancing reduces spread of the virus. The pandemic is far from over, and countries that have done well in the past may not do well in the future, and such reversals have already been seen in the last year. One lesson of this pandemic should surely be humility.

Acknowledgments

For help and comments, I thank Tim Besley, François Bourguignon, Anne Case, William Easterly, Chico Ferreira, Ian Goldin, Penny Goldberg, Gita Gopinath, Rob Joyce, Chris Papageorgiou, Sam Preston, Paul Schreyer, Joe Stiglitz and Nick Stern. Branko Milanovic provided key help by pointing me to the GHIS Index and by helping me understand how China’s growth is affecting measures of global inequality. Errors are my own. I acknowledge financial support from the National Institute of Aging through NBER, Award Number P01AG05842.

References

- 1.Goldin I, Muggah R. COVID-19 is increasing multiple kinds of inequality. Here’s what we can do about it [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/covid-19-is-increasing-multiple-kinds-of-inequality-here-s-what-we-can-do-about-it/

- 2.United Nations Development Program. Coronavirus vs. inequality [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://feature.undp.org/coronavirus-vs-inequality/

- 3.Stiglitz J. Conquering the great divide. Finance and Development. 2020. September 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Georgieva K. The Great Divergence: A Fork in the Road for the Global Economy [Internet]; 2021. Feb 24. Available from: https://blogs.imf.org/2021/02/24/the-great-divergence-a-fork-in-the-road-for-the-global-economy/

- 5.World Bank. Reversal of Fortune: poverty and shared prosperity report 2020. Washington DC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decerf B, Ferreira FHG, Mahler DG, Sterck O. Lives and livelihoods: estimates of the global mortality and poverty estimates of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9277, June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milanovic B. Worlds apart: measuring international and global inequality. Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milanovic B. Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Harvard University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deaton A. The great escape: Health, wealth, and the origins of inequality. Princeton University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: A long and difficult ascent. Washington, DC. October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank. Global Economic Prospects. Washington, DC. January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg PK, Reed T. The effects of the Coronavirus pandemic in emerging market and developing economies: an optimistic preliminary account [Internet]; 2020. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, forthcoming. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Goldberg-Reed-conference-draft.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg PK, Reed T. Update [Internet]; 2020. December. Available from: http://www.econ.yale.edu/~pg87/UPDATE_December2020.pdf

- 14.Preston SH. The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Population Studies. 1975;29(2):231–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GHIS Index. Global Health Security Index: Building collective action and accountability [Internet]; 2019. October. Available from: https://www.ghsindex.org/

- 16.Wall Street Journal. Tanzania shunned lockdowns. Now it is rejecting Covid-19 vaccines. 2021. February 03. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Obesity Federation. COVID-19 and obesity: the 2021 Atlas [Internet]; 2021. Available from: https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/COVID-19-and-Obesity-The-2021-Atlas.pdf

- 18.Heuveline P, Tzen M. Beyond deaths per capita: comparative CoViD-19 mortality indicators [Internet]; 2020. May (updated 2021 January). Available from: 10.1101/2020.04.29.20085506v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Carleton T, Cornete J, Huybers P, Meng KC, Proctor J. Global evidence for ultraviolet radiation decreasing COVID-19 growth rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. 2021;118(1). 10.1073/pnas.2012370118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee S. Why does the pandemic seem to be hitting some countries harder than others? New Yorker. 2021. March 1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troesken W. The pox of liberty: how the constitution left Americans rich, free, and prone to infection. U. Chicago Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: global manufacturing downturn, rising trade barriers. Washington, DC. 2019. October. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf M. Ten ways in which coronavirus crisis will shape world in long term. Financial Times. 2020. November 3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goolsbee A, Syverson C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. NBER Working Paper No. 27432, 2020. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster JE, Ok EA. Lorenz dominance and the variance of logarithms. Econometrica. 1999;67(4):901–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaton A, Schreyer P. GDP, wellbeing, and health: thoughts on the 2017 round of the International Comparison Program. NBER Working Paper 28177. 2020. December. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]