Cardiogenic shock is a severe, often fatal presentation of acute myocardial infarction. This report presents an unusual case of ST-segment elevation…

Key Words: cardiac assist devices, coronary angiography, coronary circulation, myocardial infarction, myocardial revascularization, percutaneous coronary intervention, postoperative

Abstract

Cardiogenic shock is a severe, often fatal presentation of acute myocardial infarction. This report presents an unusual case of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with left internal mammary artery occlusion occurring after instrumentation of the left subclavian artery as part of planned repair of a complex aortic aneurysm. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Graphical abstract

History of Presentation

A 69-year-old man with symptoms of dysphagia underwent surgical correction of an aortic arch aneurysm with an aberrant right subclavian artery. The patient was followed by cardiothoracic and vascular surgery for a Kommerell diverticulum with an aberrant right subclavian artery and a descending thoracic aortic aneurysm. Serial imaging showed interval enlargement of the descending aorta to 48 mm. Management options for this condition are not standardized and vary between open and endovascular repair. In this patient’s case, the decision was made to treat his aneurysm with a planned initial left carotid–to–left subclavian artery bypass before subsequent right subclavian bypass with thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Cardiology consultation had not been requested pre-operatively, and details of the prior coronary bypass anatomy were not documented in the pre-operative surgical notes. The patient underwent left carotid–to–left subclavian artery bypass with vascular surgery without any mention of a left internal mammary artery (LIMA). In the post-operative care unit, the patient developed cardiogenic shock, and the electrocardiogram (ECG) showed an anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Learning Objectives

-

•

To highlight the importance of understanding a patient’s vascular anatomy in the setting of prior CABG with need for emergency revascularization.

-

•

To understand the role of changing access site (from femoral to radial in this case) on the basis of a suspected culprit artery in the setting of complex aortic anatomy.

-

•

To highlight the utility of a hemodynamic support device in a patient with cardiogenic shock.

Past Medical History

The patient had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), Kommerell diverticulum with aberrant right subclavian artery, and descending thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and surgical site bleeding.

Investigations

An ECG showed ST-segment elevation in V1 and V2.

Management

The patient was taken emergently to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, and ticagrelor was administered. The exact coronary bypass graft anatomy was not known by either the vascular or cardiothoracic surgery team. Access through the left femoral artery was obtained with demonstrating native multivessel disease with a proximally occluded left anterior descending (LAD) artery. Bypass graft angiography showed patent vein grafts to second obtuse marginal branch and the distal right coronary artery. We suspected a lesion within a LIMA graft to the LAD artery as the STEMI culprit. Both surgical teams were present in the catheterization laboratory to facilitate management of this patient’s case. Use of the LIMA as a pedicle graft to the LAD artery was confirmed by review of prior chest computed tomography. However, engagement of the left subclavian artery was challenging through femoral access because of the patient’s aneurysmal aorta with Kommerell diverticulum. An aortic arch angiogram demonstrated this aneurysm, and the position of the left carotid–to–left subclavian artery graft is outlined (Figure 1). Attempts at left subclavian artery engagement failed even with vascular surgery assistance in the catheterization laboratory. The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure requiring intubation. Anticipating a challenging intervention, we elected to prioritize hemodynamic support before intervention and placed an axial flow pump hemodynamic support device through our maintained femoral access. While positioning our support device in the left ventricle, the patient developed several episodes of ventricular fibrillation requiring defibrillation. Once his condition was stabilized, we obtained left radial access, and left subclavian angiography noted what appeared to be an ostial LIMA occlusion (Figure 2). We engaged the LIMA with an internal mammary guide, and a workhorse wire was used to probe the “beak” of the suspected LIMA ostial occlusion and was passed distally down the LIMA. Subsequent angiography revealed some restoration of flow down the LIMA with a diffuse filling defect (Video 1). Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was performed and, in conjunction with the angiographic appearance of the LIMA, revealed diffuse thrombus (although some component of plaque could not be excluded) (Video 2). On the basis of IVUS, we deployed a 3.0 × 38 mm drug-eluting stent across the ostium of the LIMA. We post-dilated our stent proximally, and final angiography revealed excellent stent expansion (Figure 3). Possible iatrogenic compromise of the LIMA ostium (Figure 4) as a contributing factor to the STEMI could not be excluded. Final angiography revealed that the LIMA was sequentially grafted to a large first diagonal branch and the LAD artery (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Aortic Arch Angiogram

Kommerell’s diverticulum anatomy is shown. The left carotid–to–left subclavian artery graft is highlighted (red lines).

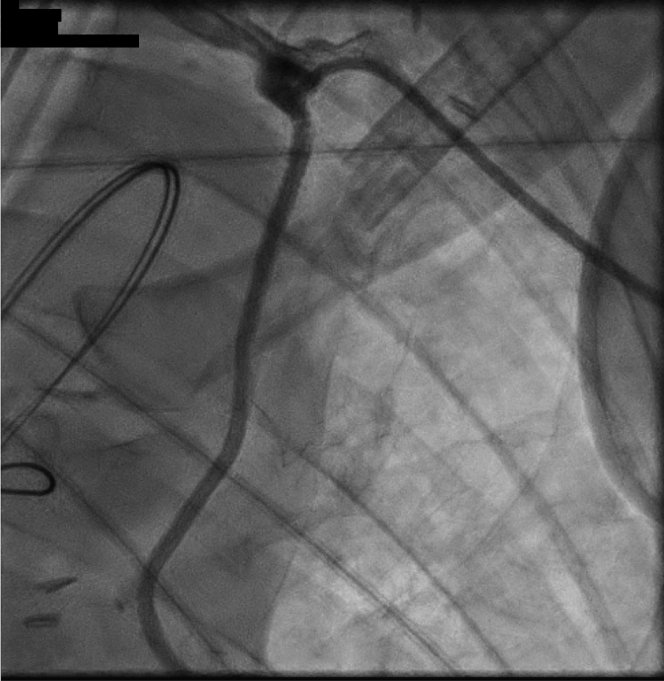

Figure 2.

Left Subclavian Angiography

Suspected ostial occlusion of the left internal mammary artery is highlighted by the arrow.

Online Video 1.

Left Subclavian Angiogram After Passing Wire Across the Suspected Lesion

Some restoration of flow down the left internal mammary artery with diffuse filling defect is shown.

Online Video 2.

IVUS of LIMA After Reperfusion

IVUS = intravascular ultrasound; LIMA = left internal mammary artery.

Figure 3.

Final PCI Result

Restoration of left internal mammary artery flow is demonstrated. PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 4.

Status Post-PCI With DES Placement

Possible external compression of the ostium is shown (red box). DES = drug-eluting stent; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 5.

Delineation of Final Anatomy

Previous 4-vessel coronary artery bypass graft with a sequential left internal mammary artery graft to a large proximal diagonal and then the left anterior descending is shown.

Discussion

This is an unusual cause of anterior STEMI secondary to occlusion of the ostial LIMA in the setting of left subclavian artery surgery. This case emphasizes the need for pre-procedural awareness and documentation of prior CABG anatomy when surgical manipulation in the area of the bypass graft will occur. Given the anterior location of the STEMI on the ECG, the clinical presentation of cardiogenic shock, and the patient’s recent history of left subclavian artery instrumentation, we suspected an occluded LIMA-LAD graft; however, this could not be confirmed from discussion with cardiothoracic or vascular surgery. A unique challenge in this case was the need to convert from femoral to radial arterial access on the basis of the suspected culprit artery after subclavian engagement through the femoral approach failed. Once final percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was completed, delineation of the graft anatomy revealing the LIMA as a sequential graft to the LAD and large diagonal branch further explained the patient’s acute shock presentation.

Hemodynamic support devices are used in high-risk interventional procedures to maintain cardiac output and reduce left ventricular wall stress. Hemodynamic instability and an intervention in an artery that supplies a large area of viable myocardium (such as the LIMA graft) are current indications for using hemodynamic support devices (1). In our case, hemodynamic support allowed us to stabilize the patient and thus provided time to perform a complex LIMA intervention using IVUS guidance.

Multiple causes of iatrogenic occlusion of the LIMA ostium during left carotid–to–left subclavian artery grafting are possible. In the course of such a complex operation, an arteriotomy is made in the left subclavian artery, and a polytetrafluoroethylene graft is anastomosed to both this vessel and the left common carotid artery (Figure 1). It is possible that the anastomosis compressed or led to narrowing or occlusion of the ostium of the nearby LIMA. Plaque shift from the left subclavian artery into the origin of the LIMA is also possible. IVUS was performed only after the ostium of the LIMA was balloon dilated because the priority was prompt restoration of antegrade flow; thus, intracoronary imaging was not able to assist in differentiating one cause from another.

Follow-Up

Post-PCI, the patient required a red blood cell infusion as a result of surgical site bleeding requiring brief interruption of antiplatelet therapy. Pressor requirements declined post-PCI, and hemodynamic support was weaned. Left ventricular function was noted to be 30% to 35%, with apical and anteroseptal akinesis. A repeat transthoracic echocardiogram 4 months later showed an ejection fraction of 55% with no residual wall motion abnormalities. At 5 months after PCI, the patient underwent successful right carotid–to–right subclavian artery bypass and thoracic endovascular aortic repair as originally intended.

Conclusions

This is a case of a 69-year-old man with a history of CABG (anatomy not documented by interdisciplinary surgical team) who developed anterior STEMI and cardiogenic shock shortly after left carotid–to–left subclavian artery bypass secondary to an occluded proximal LIMA graft to the diagonal and middle LAD artery. The LIMA occlusion was suspected to have occurred during surgical manipulation of the left subclavian artery. The occlusion was successfully revascularized while using axial flow pump support with excellent angiographic, clinical, and long-term outcomes.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

Reference

- 1.Alkhatib B., Wolfe L., Naidu S.S. Hemodynamic support devices for complex percutaneous coronary intervention. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2016;5:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.iccl.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]