ABSTRACT

The clinical effects of remimazolam (an investigational, ultra‐short acting benzodiazepine being studied in procedural sedation) were measured using the Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S). The objective of this analysis was to develop a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model to describe remimazolam‐induced sedation with fentanyl over time in procedural sedation. MOAA/S from 10 clinical phase I–III trials were pooled for analysis, where data were collected after administration of placebo or remimazolam with or without concomitant fentanyl. A Markov model described transition states for 35,356 MOAA/S‐time observations from 1071 subjects. Effect‐compartment models of remimazolam and fentanyl linked plasma concentrations to the Markov model, and drug effects were described using a synergistic maximum effect (Emax) model. Simulations were performed to identify the optimal remimazolam‐fentanyl combination doses in procedural sedation. Fentanyl showed synergistic effects with remimazolam in sedation. Increasing age was related to longer recovery from sedation. Patients with body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 had ~30% higher rates of distribution from plasma to the effect site (keo), indicating a slightly faster onset of sedation. Simulations showed that remimazolam 5 mg was more appropriate than 4 or 6 mg when administered with fentanyl 50 μg. The model and simulations support that a combination of remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg is an appropriate dosing regimen and the dose of remimazolam does not need to be changed in elderly patients, but some elderly patients may have a longer duration of sedation.

Study Highlights.

-

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

A pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model of remimazolam is available for the bispectral index, but the relationship to sedation (measured by Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale) in procedural sedation is unknown.

-

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

What is the optimal dose of remimazolam when administered with fentanyl in procedural sedation and are there subgroups that require dosage adjustments?

-

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

Exposure‐response modeling supported the recommended dose (remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg) in procedural sedation and showed that the dose of remimazolam does not need to be changed in elderly patients, but some elderly patients may have a longer duration of sedation.

-

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

Using a Markov model resulted in excellent agreement of observed and predicted transitions between sedation states but did less well at predicting the actual level of sedation. The magnitude of “deep sedation” was overpredicted. Relative differences among dosing regimens can still be assessed to support dose selection when the bias is consistently conservative. Thus, the conservativeness of a model should be considered in the interpretation of modeling and simulation results.

INTRODUCTION

Remimazolam is an ultra‐short acting benzodiazepine administered by i.v. injection or infusion, which is approved for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia in Japan (Anerem) and procedural sedation in the United States (ByFavo) and China (Ruima). Remimazolam is rapidly hydrolyzed by liver carboxylesterase 1 to an inactive metabolite (CNS7054) 1 and is, therefore, superior to midazolam with its rapid and predictable onset and offset. 2 Remimazolam may be used with fentanyl to minimize discomfort level during uncomfortable medical procedures (e.g., colonoscopy or bronchoscopy).

Remimazolam’s phase III studies were initiated using a 5‐mg dose administered (with 2.5 mg top‐up doses) with fentanyl 75 µg (with 25 µg top‐up doses) 3 , 4 to target a Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S) 5 of 2–3 (representing “moderate sedation”) required for successful procedural sedation, with the understanding that a successful procedure may be performed with an MOAA score of 0–3, but “deep sedation” (MOAA/S score of 0–1) should be avoided because these subjects are not intubated. Early in the conduct of the study, the Data‐Safety‐Monitoring Committee reviewed cases of unintentionally deep sedation (e.g., MOAA/S of 0–1) and recommended a decrease in the initial fentanyl dose to 50 µg (or lower in elderly patients), with no changes in the remimazolam dose. 3 , 4 , 6

Unintentionally, deep sedation at higher doses of fentanyl appeared to be related to the synergistic effects between benzodiazepines and opioids, 7 , 8 , 9 which were reported for a previous population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PopPK/PD) analysis of remimazolam and remifentanil in general anesthesia using bispectral edge (BIS). 10 Sedation using BIS is not directly correlated with sedation measured using the MOAA/S in procedural sedation. 11 Therefore, a PopPK/PD model was developed to improve the understanding of the relationship between remimazolam plasma concentrations (Cp) with or without fentanyl and MOAA/S to support the dose rationale for concomitantly administered fentanyl and remimazolam in procedural sedation. Development of this PopPK/PD model allowed simulations to evaluate the appropriateness of the phase III dosing regimen in the overall population and in subpopulations with different PK/PD characteristics.

Given that sedation at any given time is dependent on sedation at a previous timepoint, a Markov model is more appropriate to evaluate PK/PD of remimazolam than an ordinal logistic regression model. Markov models describe the drug’s effects on the transition from the previous state of sedation to the present sedation state to allow for more realistic simulations. 12 Therefore, the overall goals of this analysis were to describe remimazolam‐induced sedation over time in the presence of fentanyl, to evaluate what factors affect PD parameters, and to simulate various doses to evaluate the optimal dose.

METHODS

Subject data

Sedation data from 10 phase I–III studies described in Table S1 were pooled for PopPK/PD analysis. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice, across Japan, the United States, and the European Union. All studies were approved by ethics committees (Table S1, along with clinical‐trial registry numbers and registration dates) and written informed consent was obtained prior to study procedures. These studies included:

Five phase I studies in healthy subjects (ONO‐2745–01, 13 ONO‐2745–02, 13 ONO‐2745IVU007, 14 CNS7056‐001, 15 and CNS7056‐017 16 );

Two phase II studies in procedural sedation (CNS7056‐002, 17 and CNS7056‐004 18 );

Three phase III studies in procedural sedation (CNS7056‐006, 3 CNS7056‐008, 4 and CNS7056‐015 6 ).

For procedural sedation studies, subjects received an initial i.v. remimazolam dose of 5 to 8 mg administered over 1 min, followed, if required, by 1 mg, 2 mg, 2.5 mg, or 3 mg top‐up doses, at least 3 min apart depending on the study. 3 , 4 , 6 , 18

One study (ONO‐2745–02) 13 in healthy subjects had an up to 1‐h i.v. infusion of remimazolam 1 mg/kg/hr. A second study (CNS7056‐017 16 ) in healthy subjects infused remimazolam i.v. at 5 mg/min for 5 min, then 3 mg/min for 15 min, and then 1 mg/min for 15 min. For 3 other healthy subject studies (ONO‐2745–01, 13 ONO‐2745‐IVU007, 14 and CNS7056‐001 15 ), i.v. bolus remimazolam doses of 0.01 to 0.5 mg/kg were administered.

MOAA/S, a validated scale for measuring the level of sedation (5 = complete alertness, 0 = completely unresponsive), was measured before and after administration of placebo and remimazolam with and without fentanyl. 5 To simplify Markov modeling, MOAA/S score was recoded into 4 recoded MOAA/S (RCMOAA) groups (Figure 1): RCMOAA of 4 (“not sedated”) was equivalent to a MOAA/S of 5; RCMOAA of 3 (“light sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 4; RCMOAA of 2 (moderate sedation) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 3 or 2; RCMOAA of 1 (deep sedation) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 1 or 0; and RCMOAAS of 6 was used for “inadequate sedation” (resulting in rescue medication).

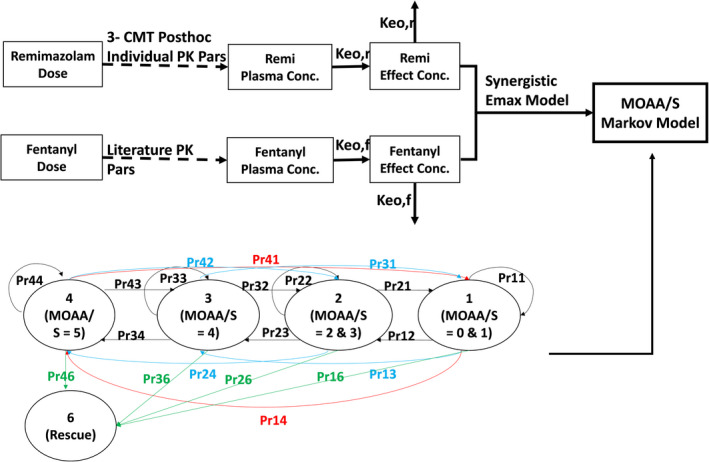

FIGURE 1.

PK/PD model for remimazolam. keor and keof describe the rates of equilibrium between plasma concentrations and sedation for remimazolam and fentanyl, respectively. RCMOAA of 4 (“not sedated”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 5; RCMOAA of 3 (“light sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 4; RCMOAA of 2 (“moderate sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 3 or 2; RCMOAA of 1 (“deep sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 1 or 0; and RCMOAAS of 6 was used for “inadequate sedation” (resulting in rescue medication). Pr = Transition probabilities (probabilities for subjects being in each of the four states at each time point conditioned on their previous state) defined using two digits (first = previous score, second = current score). Numbers of subjects in the following transitions were too small to be modeled: P41, P42, P31, P13, and P14. MOAA/S, Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; PD, pharmacodynamic; PK, pharmacokinetic; RCMOAA, recoded Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale

The analysis population included all subjects in the per protocol population who had at least one MOAA/S score.

General modeling methods

NONMEM version 7.3 (ICON Development Solutions) was used to develop the model using the numerical Laplacian method with Centering and Likelihood options. Graphical analyses and visual predictive checks (VPCs) were performed using R version 3.0.2 and Xpose version 4.5.3; bootstrapping was conducted using Perl‐speaks‐NONMEM program version 4.4.0.

Remimazolam exposure

Empiric Bayes Estimates (EBE) of PK parameters from a previously developed PopPK model 19 were used to predict remimazolam Cp at the time of each RCMOAAS score for 319 subjects with Cp data. In subjects with PD (but no PK) data, individual PK parameters were simulated based on PopPK parameters, including relevant covariates for predictions of Cp at the time of each MOAA/S score. If the subject received placebo, Cp was assumed to be 0.

Fentanyl exposure

Because fentanyl Cp were not collected and fentanyl doses are given at different times in each individual subject, published PK parameters 20 were used to simulate the population‐predicted fentanyl Cp‐time profile after each dose. The parameters for a 3‐compartment model included clearance (0.574 L*min−1), central volume (V1; 12.7 L), volumes of distribution of the peripheral compartments (V2; 54.2 L and V3, 272 L), and intercompartmental clearances (Q2; 4.93 L*min−1 and Q3, 2.53 L*min−1).

Model

Figure 1 illustrates the overall model process, including the 20 transition probabilities between sedation status and rescue states. Transition probabilities (i.e., probabilities for subjects being in each of the 4 states at each timepoint conditioned on their previous state) are defined using two digits (first = previous score, second = current score).

The NONMEM control stream is included in Figure S1, which describes the Markov equations. Drug effects were added to relative probability on natural log scale :

| (1) |

Where φ km reflects the baseline log‐transformed relative probability of k → m transition without drug effects; fd km(q(t) i , j ) denotes the additional drug effects on k → m transition probability; ti , j is the time for the j th observation in the i th subject; q(t) i , j is the corresponding effect‐compartment drug concentration; ηi is a proportional error model representing the random effect for subject i. There were no random effects for rescue probabilities because subjects can only be rescued once.

Drug effects on transitional probabilities fd km(q(t) i , j ) were modeled as maximum effect (Emax):

| (2) |

Where drug effects on each transition probability were incorporated into respective logit expressions and Emaxkm is the drug‐related magnitude for the k → m transition; EC50 i is the potency (half‐maximal effective concentration) of Emax for the i th subject; and Ce (i,j) is the drug concentration at the effect site for the i th subject at the j th observation, where keo describes the disequilibrium between plasma and effect site concentrations.

Table S2 outlines the development of fixed and random effects. Interindividual variability (IIV) was added to the EC50 and keo of remimazolam using a proportional error model. After unsuccessfully attempting IIVs on separate transitions, one universal random effect (ETA) was used on all downward transitions and one ETA on all upward transitions. Numbers of subjects in the following transitions were too small to have ETA estimated: P41, P42, P31, P13, and P14.

Covariates

The prespecified covariates were the effect of fentanyl Cp on remimazolam’s EC50, and the effects of sex, race, age, body mass index (BMI), procedure type, and American Society of Anesthesiology Classification (ASA class) on the transition probabilities, EC50, and/or keo of remimazolam. Effects of covariates on fentanyl’s PD parameters were not evaluated given, only population‐predicted fentanyl concentrations were available.

If shrinkage was adequate, effects were evaluated only if plots of EBEs versus the covariate suggested a relationship. If shrinkage was greater than 45%, covariates were tested using forward addition and only included if the objective function value decreased by 10.828 (p < 0.001 with 1 degree of freedom) and there was adequate precision of estimates and biological plausibility.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate how randomness in PK (from subjects with no Cp) contributed to the PD parameter estimates by using typical values from the PopPK model for subjects without Cp and the individual predicted parameters for subjects with Cp.

Another sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the data from healthy subjects (with different dosing and less frequent MOAA/S sampling) influenced the PD parameters by re‐running the model with data from bronchoscopy and colonoscopy patients only (with similar dosing and observation times).

Model performance

Model parameter precision was assessed using nonparametric bootstrapping stratified by study with 250 runs (due to long run time); then, the median and 95% confidence intervals of parameter estimates were calculated and compared with NONMEM output.

Model fitting was assessed using simulation‐based goodness‐of‐fit plots (VPCs). Monte Carlo simulations (n = 500) using fixed model parameters were used to calculate transition probabilities over independent variables (times, remimazolam effect‐site concentrations, and synergistically combined remimazolam + fentanyl effect‐site concentrations). The resulting simulated data were overlayed with observed probabilities for evaluation of model performance.

Parameter predictive checks were also implemented to evaluate the model performance by comparing the observed and predicted proportions of subjects achieving each minimum RCMOAA score. For each simulation, the predicted minimum RCMOAA was reported based on three equal consecutive minimum values to account for randomness. Subsequently, the proportions of subjects achieving each minimum RCMOAA were determined for each simulation. Observed data were summarized similarly. Once all simulations were completed, the average percentage of subjects achieving each minimum RCMOAA score was compared with observed data.

Simulations

Simulations were conducted for the following combinations of a single dose of remimazolam and fentanyl (1000 subjects per dose combination × 100 replicates):

Remimazolam 4 mg with fentanyl 50 or 75 μg

Remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 25, 50, or 75 μg

Remimazolam 6 mg with fentanyl 25 or 50 μg.

Where fentanyl was administered over 2 min, and then remimazolam administered over 1 min immediately after completion of fentanyl (referred to as 2 min apart).

Simulations were conducted assuming 75% of subjects were less than 65 years old and 25% of subjects were greater than 65 years old; half were men and half were women; half were African Americans and half were White, Asian, or other; half had a normal BMI and half had a BMI greater than >25 kg/m2; and all subjects had colonoscopies, so that each subgroup would have sufficient subjects to allow an interpretation.

Sedation scores were collected every 0.5 min from the start of fentanyl administration to 7 min, then every 1 min thereafter up to 15 min. Plots and tables were produced summarizing the proportion of subjects achieving benchmarks: moderate sedation, deep sedation, “light sedation, and not sedated over time.

RESULTS

Figure S2 illustrates 35,356 observations from 1071 subjects included in analysis. Significant sedation was observed for 50–70 min after 1–5 doses of remimazolam. There were many observations of RCMOAA = 4 at later times when recovery was complete. After placebo‐only administration, there were 2 instances of RCMOAA = 3 and all other observations were RCMOAA = 4 with no time‐related placebo effect. Following fentanyl with placebo administration, light sedation lasted up to 100 min.

Table S3 summarizes demographics and other covariates. Subjects included 53.2% men and 46.8% women, who were mostly White with 17.5% African Americans and 7.7% Asians. Nearly one‐third of subjects were obese. More than one‐third of subjects were ASA class 1, 46.4% of subjects were ASA class 2, 16.3% were ASA class 3, and 1.6% were ASA class 4. The average age of subjects was 53.8 years, with 224 elderly (≥65 years) patients. Initial remimazolam doses ranged from 0.662 to 38.6 mg. Total doses of remimazolam ranged from 0.662 to 85.0 mg and total doses of fentanyl ranged from 25 to 225 μg.

Base model

Table S2 describes base model development. In general, the need for different Emax models for each transition probability was evaluated, followed by the need for separate ETAs on each transition probability. Evaluation of different Emax values for different downward transitions was not successful. Therefore, two separate Emax models were used, one for downward transition probabilities and one for upward transition probabilities. The effect of fentanyl was evaluated assuming a synergistic effect on remimazolam EC50.

The base model was an effect‐compartment model with effects of fentanyl on remimazolam EC50 7 , separate keo for remimazolam and fentanyl, one ETA on remimazolam keo, one ETA on remimazolam EC50, one Emax model and one ETA for downward transitions, one Emax model and one ETA for upward transitions (Figure 1).

Covariates

Because the shrinkage was high for keo and the downward transitions, covariates were tested using forward addition. Shrinkage was acceptable for the ETAs on EC50 and for upward transitions; thus, covariates that appeared to have a relationship between the covariate and the EBEs were tested. Covariate testing resulted in (Table S2):

A linear effect of age (centered on median age) on upward transitions

An effect of BMI (<25 kg/m2 vs. >25 kg/m2) and the effect of procedure type (bronchoscopy vs. colonoscopy vs. healthy subjects) on keo.

There were no effects of age or sex on the downward transitions.

Final PK/PD model

The final model was the same as the base model with an effect of age on upward transitions, an effect of BMI on keo, and an effect of procedure type on keo (Table 1). Parameter estimates (except G13) were estimated with good precision. Shrinkage was adequate for EC50 (31%) and upward transition probabilities (41%) but high for keo and downward transition probabilities (66–69%).

TABLE 1.

NONMEM parameter estimates and estimates from a nonparametric bootstrap for the population PK/PD model of remimazolam

| PK/PD model parameter |

Estimate (%RSE) [Bootstrap a median (2.5th–97.5th percentile)] |

|---|---|

| keo for remimazolam, min−1 | 0.619 (11.9%) [0.617 (0.478–0.787)] |

| IIV on keo remimazolam, CV% | 36.8% (22.6%) [36.3% (27.4−43.5%)] |

| Effect of BMI >25 kg/m2 on keo | 1.29 (8.5%) [1.30 (1.04–1.55)] |

| Effect of bronchoscopy relative to HV on keo | 1.25 (13.5%) [1.25 (0.904–1.82)] |

| Effect of colonoscopy relative to HV on keo | 1.78 (13.0%) [1.80 (1.35–2.32)] |

| EC50 for remimazolam, μg/ml | 0.258 (8.7%) [0.257 (0.201–0.334)] |

| IIV on EC50 for remimazolam, CV% | 35.3% (4.8%) [35.8% (32.1−38.9%)] |

| keo for fentanyl, min−1 | 0.569 (14.6%) [0.588 (0.199–1.25)] |

| EC50 for fentanyl, ng/ml | 2.30 (10.3%) [2.29 (1.76–3.17)] |

| Beta U parameter | −2.20 (10.4%) [−2.23(−2.83 to −1.62)] |

| Emax for remimazolam, downward transitions | 11.6 (2.4%) [11.8 (11.0–12.6)] |

| IIV on downward transitions | ±0.453 (11.6%) [0.444 (0.266–0.616)] |

| G43 | −7.24 (2.9%) [−7.29 (−7.81 to −6.82)] |

| G42 | −8.03 (2.7%) [−8.07 (−8.63 to −7.53)] |

| G41 | −9.21 (2.6%) [−9.28 (−9.78 to −8.74)] |

| G32 | −6.72 (3.2%) [−6.81 (−7.38 to −6.30)] |

| G31 | −8.49 (2.6%) [−8.60 (−9.16 to −8.03)] |

| G21 | −9.19 (−2.4%) [−9.27 (−9.85 to −8.83)] |

| Emax for remimazolam, upward transitions | 5.12 (4.1%) [5.17 (4.69–5.76)] |

| IIV on upward transitions | ±0.594 (6.1%) [0.597 (0.522–0.652)] |

| G12 | 1.21 (10.9%) [1.27 (0.925–1.63)] |

| G13 | 0.218 (67.3%) [0.257 (−0.156 to 0.655)] |

| G14 | −2.33 (14.5%) [−2.26 (−3.00 to −1.72)] |

| G23 | 1.09 (10.6%) [1.14 (0.82–1.43)] |

| G24 | −1.64 (−8.7%) [−1.60 (−1.94 to −1.29)] |

| G34 | −0.224 (−40.5%) [−0.176 (−0.464 to 0.116)] |

| Placebo dropout | 2.81 (7.1%) [2.81 (2.49–3.16)] |

| G46 | −6.01 (3.4%) [−6.01 (−6.35 to −5.72)] |

| G36 | −5.37 (−3.2%) [−5.38 (−5.70 to −5.10)] |

| Slope of age effect on upward transitions, modeled as slope x(AGE−54)/AGE | −1.19 (8%) [−1.21 (−1.52 to −0.937)] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EC50, half‐maximal effective concentration; Emax, maximum effect; CV%, coefficient of variation percentage; HV, healthy volunteers; IIV, interindividual variability; keo, rates of distribution from plasma to the effect site; PD, pharmacodynamic; PK, pharmacokinetic.

The bootstrap is resource intensive and exceeded computation capability when running 250 bootstraps. Ultimately, there were 169 successful bootstrap runs retrieved for parameter summary. Gx,y) is the relative probability on natural log scale from the x sedation score to the y sedation score.

Model performance

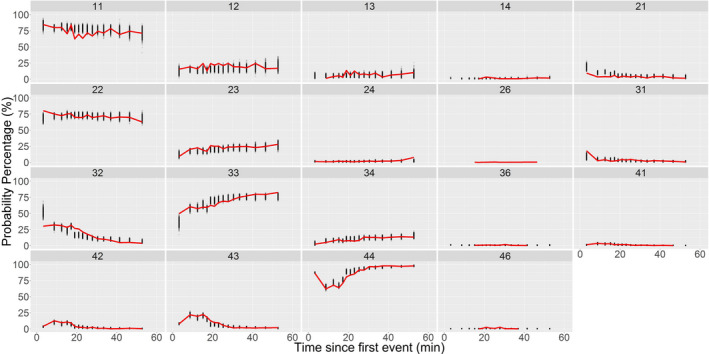

Bootstrap: Parameters from nonparametric bootstrapping were nearly identical to NONMEM estimates, except for G13 and G34, which differed by 13–27% (Table 1). VPC: Goodness‐of‐fit plots showed agreement between observed and predicted transition probabilities by treatment:

Transition probabilities versus time (Figure 2),

Transition probabilities versus remimazolam effect site concentrations (Figure S3), and

Transition probabilities versus fentanyl and combined effect site concentrations (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Observed and simulated transition probabilities versus time since first event for patients receiving remimazolam. Time since first event with the most likely event being a predose observation but the event could have been during placebo, a fentanyl, remimazolam administration. Observed probabilities = red line, predicted probabilities from 500 simulations = black dots; transitions described using two digits (first = previous score, second = current score)

Predictive Parameter Check: Predicted and observed data matched well for colonoscopy patients after the first dose (Table 2), showing the model was appropriate for simulation.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of observed and predicted proportions of minimum RCMOAA scores by study for the first dose and subsequent doses

| Patient type | Dose no. | Observed | Simulated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCMOAA = 1 (deep sedation) | RCMOAA = 2 (moderate sedation) | RCMOAA = 3 (mild/light sedation) | RCMOAA = 4 (not sedated) | RCMOAA = 1 (deep sedation) | RCMOAA = 2 (moderate sedation) | RCMOAA = 3 (mild/light sedation) | RCMOAA = 4 (not sedated) | ||

| Healthy subjects | 1st | 48.1 | 23.6 | 7.5 | 20.8 | 27.8 | 23.4 | 19.4 | 29.5 |

| Healthy subjects | ≥2nd | 100 | NA | NA | NA | 95.2 | 4.7 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Colonoscopy | 1st | 24.6 | 47.5 | 16.7 | 11.1 | 22.9 | 40.3 | 16.9 | 19.9 |

| Colonoscopy | ≥2nd | 19.8 | 57.9 | 18.1 | 4.2 | 26.4 | 38.6 | 21.5 | 13.4 |

| Bronchoscopy | 1st | 4.3 | 44.4 | 23.7 | 27.6 | 14.4 | 34.1 | 18.0 | 33.4 |

| Bronchoscopy | ≥2nd | 3.5 | 71.3 | 16.7 | 8.5 | 29.2 | 40.0 | 18.2 | 12.6 |

Bolded values mean overpredicted by >10%, italic values mean underpredicted by >10%.

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable, RCMOAA, recoded Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale.

In bronchoscopy patients, the model overestimated the proportion of subjects with deep sedation and underestimated the proportion of subjects with moderate sedation. Therefore, only colonoscopy patients after the first dose were used for simulations.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis showed that the lack of PK data in some patients did not influence the PD parameter estimates. Results from the sensitivity analysis, excluding healthy subjects, showed that patients had a lower EC50 for remimazolam and fentanyl, a lower Emax for upward transitions, a higher G13 (suggesting a greater likelihood of recovery from deep sedation), and a lower G34 (suggesting a lower likelihood of recovery from light sedation to not sedated). Use of this model did not improve the consistency of observed and predicted data for bronchoscopy patients and was not utilized further.

Simulations

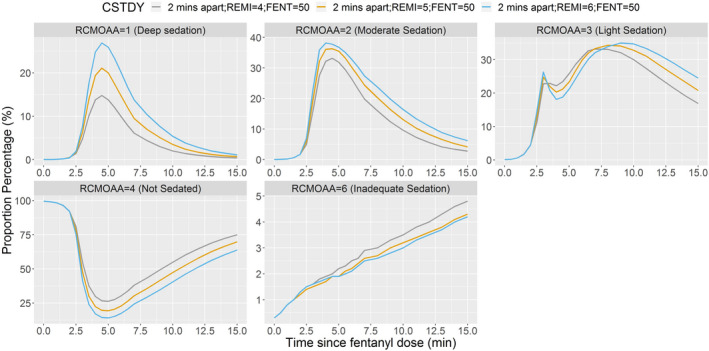

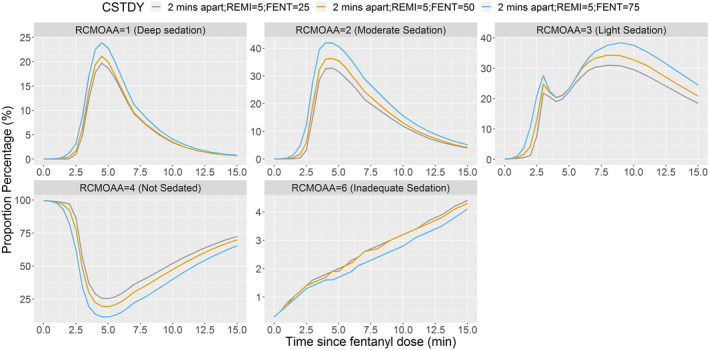

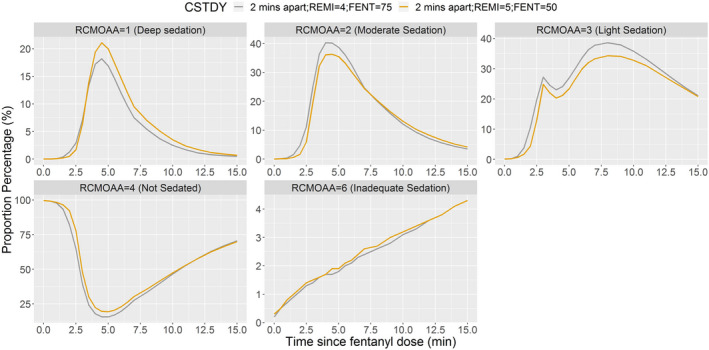

When remimazolam and fentanyl were administered together (2 min apart), remimazolam 5 mg appeared to be more appropriate than 4 or 6 mg when administered with fentanyl 50 μg (Figure 3). Fentanyl 50 μg appeared to be more appropriate than 25 μg or 75 μg, when administered with remimazolam 5 mg (Figure 4). Remimazolam 6 mg produced deep sedation when given with fentanyl 50 μg (Figure 3). Although a minor advantage of remimazolam 4 mg with fentanyl 75 μg over remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg cannot be ruled out (Figure 5), this advantage was just above the level of random chance.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of subjects at each RCMOAA score when fentanyl 50 μg is administered with remimazolam 4, 5, or 6 mg (2 min apart). Fentanyl administered over 2 min, and then remimazolam administered over 1 min immediately after completion of fentanyl = 2 min apart. RCMOAA of 4 (“not sedated”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 5; RCMOAA of 3 (“light sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 4; RCMOAA of 2 (“moderate sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 3 or 2; RCMOAA of 1 (“deep sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 1 or 0; and RCMOAAS of 6 was used for “inadequate sedation” (resulting in rescue medication). Fentanyl 50 μg administered with remimazolam 4 mg (gray line), 5 mg (orange line), or 6 mg (blue line). CSTDY, simulated study cohort; FENT, fentanyl; MOAA/S, Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; RCMOAA, recoded Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; REMI, remimazolam

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of subjects at each sedation score when remimazolam 5 mg is administered with fentanyl 25, 50, or 75 μg (2 min apart). Fentanyl administered over 2 min, and then remimazolam administered over 1 min immediately after completion of fentanyl = 2 min apart. RCMOAA of 4 (“not sedated”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 5; RCMOAA of 3 (“light sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 4; RCMOAA of 2 (“moderate sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 3 or 2; RCMOAA of 1 (“deep sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 1 or 0; and RCMOAAS of 6 was used for “inadequate sedation” (resulting in rescue medication). Remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 25 μg (gray line), 50 μg (orange line), or 75 μg (blue line). CSTDY, simulated study cohort; FENT, fentanyl; MOAA/S, Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; RCMOAA, recoded Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; REMI, remimazolam

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of subjects at each RCMOAA score when remimazolam 5 mg is administered with fentanyl 50 μg or remimazolam 4 mg is administered with fentanyl 75 μg (2 min apart). Fentanyl administered over 2 min, and then remimazolam administered over 1 min immediately after completion of fentanyl = 2 min apart. RCMOAA of 4 (“not sedated”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 5; RCMOAA of 3 (“light sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 4; RCMOAA of 2 (“moderate sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 3 or 2; RCMOAA of 1 (“deep sedation”) was equivalent to an MOAA/S of 1 or 0; and RCMOAAS of 6 was used for “inadequate sedation” (resulting in rescue medication). Fentanyl 75 μg administered with remimazolam 4 mg (gray line) and fentanyl 50 μg administered with remimazolam 5 mg (orange line). CSTDY, simulated study cohort; FENT, fentanyl; MOAA/S, Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; RCMOAA, recoded Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale; REMI, remimazolam

The pattern for elderly subjects receiving remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg was similar, with a trend for a 4–6% increase in the proportion of subjects with deep sedation and moderate sedation, and a trend for a 4–6% decrease in the proportion of subjects with light sedation and not sedated, when compared with subjects less than 65 years old (Figure S4). In addition, the duration of sedation was slightly (2–3 min) longer in elderly patients.

DISCUSSION

A PopPK/PD model for remimazolam was developed that describes the sedation scores over time in procedural sedation patients. The most important covariate was fentanyl co‐administration, as expected, given the synergistic relationship between benzodiazepines and opioids. 7 , 8 , 9 Race, sex, BMI greater than 25 kg/m2, and procedure type had small, but not clinically relevant effects, on remimazolam‐induced sedation. Although age has no effect on the PK of remimazolam, it was associated with small differences in the sedation levels between elderly patients and younger patients. The availability of a PopPK/PD model for remimazolam allowed for the evaluation of scenarios with different doses of remimazolam and fentanyl. The model supports that remimazolam 5 mg administered 2 min after initiation of administration of fentanyl 50 μg is appropriate, relative to other doses and combinations with fentanyl.

A Markov model, which described the transitions between sedation states over time following remimazolam administration with an effect of fentanyl on EC50, described the probabilities of various transitions over time. The main objective for development of this PopPK/PD model was to evaluate whether the remimazolam and fentanyl doses (remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg) used in phase III procedural sedation studies were optimal.

The simulations showed that remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg (the phase III dose) is an appropriate dose, providing a higher proportion of subjects that had moderate sedation balanced with a lower proportion of subjects that had deep sedation, relative to other doses. Remimazolam 4 mg with fentanyl 75 μg had a trend for a higher (~5%) proportion of patients that had moderate sedation, but a similar proportion of patients that had deep sedation compared with remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg. Although a minor advantage to remimazolam 4 mg with fentanyl 75 μg over remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg cannot be ruled out, this advantage (which is just above the level of random chance, <4%) does not warrant changing the recommended dose from that used in phase III studies, given the large safety database with colonoscopy patients receiving remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg. Moreover, the 5 mg bolus dose of remimazolam allows for a lower dose of fentanyl, an advantage in the times of the opioid epidemic.

All conclusions were based on relative (and not absolute) changes given that the simulations suggest that there may not be an absolute “ideal” dose from the model where very few (<2.5%) subjects who had deep sedation or were not sedated and greater than 95% of subjects had either moderate sedation or light sedation. It is important to note that even in colonoscopy patients (where there was good agreement between observed and predicted sedation scores), there is a slight (<10%) overprediction of the proportion of subjects who had deep sedation. This overprediction is likely a consequence of the fact that only one Emax model was used for all downward transitions and one Emax model was used for upward transitions. In reality, a different Emax model for each transition may describe the data (e.g., the relationship may differ when going from not sedated to light sedation compared with going from moderate sedation to deep sedation), but this could not be assessed in the current model given its complexity (>30 unsuccessful models, each with >10 h run times using 10 parallelized NONMEM runs on a 16‐core machine). A Markov model has not been studied with midazolam or propofol, so it is difficult to make comparisons across drugs in procedural sedation. Overall, the present model for remimazolam may have a systematic error that overpredicts sedation, but this bias is in the same direction for all simulation scenarios and is conservative (i.e., more sedation than likely). Therefore, the model remains useful to compare sedation scores across dosing regimens, but the absolute proportion of subjects with deep sedation will be overestimated.

An effect compartment model was chosen over other potential models given that this model was developed for anesthetics with a delay between the drug in plasma and the site of action as the most important factor explaining drug onset. 21 , 22 , 23 Remimazolam’s effect‐site half‐life (t½keo, 1.1 min, respectively) was shorter than previously reported in healthy subjects from two studies (2.7 16 and 2.8 15 min) and much shorter than reported in Chinese subjects receiving remimazolam (14 min 24 ). This discrepancy may be due to more intensive observations in the current analysis, differences in patient populations, or concomitant use of fentanyl.

Few covariate effects (other than the synergistic effect of fentanyl) explained variability in the PD parameters of remimazolam. Small effects of BMI on keo (which was reported for the model for BIS scores in the general anesthesia population 10 ) and of procedure type on keo (with a 1.78× faster and 1.24× faster equilibrium between plasma concentrations and sedation in colonoscopy patients and bronchoscopy patients, respectively, relative to healthy subjects) were identified. These changes do not alter the magnitude of sedation but may lead to very small changes in the time of onset, which are not likely to be clinically relevant.

The most important demographic covariate effect was the small effect of increasing age on decreasing upward transition probabilities. The magnitude of the effect of age on sedation can only be assessed based on simulations. The simulations showed a trend (4–6%) for an increased proportion of elderly subjects that had deep sedation and moderate sedation, and a trend for a 4–6% decrease in the proportion of subjects with light sedation and were not sedated, when compared with subjects less than 65 years of age. In addition, the duration of sedation was slightly (2–3 min) longer. Thus, even though there is no effect of age on the PK of remimazolam, there appears to be a PD effect related to increased age that is small and unlikely to be clinically relevant in most elderly patients. The dose of remimazolam does not need to be changed in elderly patients, but some elderly patients may have a longer duration of sedation.

The main limitation of the model is that whereas the observed and predicted probabilities were well matched, the observed and predicted sedation scores were less well matched. When the transition probabilities were converted to actual sedation scores, it was clear that the model predicted sedation scores reasonably well (within ~10%) in colonoscopy patients but overestimated the sedation in bronchoscopy patients.

A second limitation is that the discrete Markov model chosen for modeling assumed that the interval between observations is the same throughout. All procedural sedation studies had MOAA/S every 0.5 min during onset and every 1 min during recovery but phase I studies had MOAA/S less frequently during onset and recovery. A sensitivity analysis with only procedural sedation studies did not result in improvements between predicted and observed sedation scores. Nonetheless, improvement in goodness‐of‐fit with the use of a continuous time Markov model, 25 which was not attempted, cannot be ruled out. Importantly, the current model does well at predicting sedation scores in colonoscopy patients, which is the largest population, and is conservative in bronchoscopy patients.

A third limitation of the simulations is the fact that a successful procedure can be completed with the balance of fentanyl and remimazolam and may be successful when subjects had light sedation, even though moderate sedation is targeted for the majority of patients. Therefore, there is not a uniform correlation between sedation scores and the ability to complete a successful procedure.

Overall, PopPK/PD modeling supported the recommended dose (remimazolam 5 mg with fentanyl 50 μg) in procedural sedation and showed that the dose of remimazolam does not need to be changed in elderly patients, but some elderly patients may have a longer duration of sedation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

V.S., J.Z., L.C., L.L., and N.D. are paid consultants for Paion AG. J.O., F.S., and T.S. are/were employees of Paion GmbH.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Z., V.S., F.S., and T.S. wrote the manuscript. V.S., F.S., J.O., and T.S. designed the research. J.Z., L.C., L.R.L.L., N.D., and V.S. performed the research. J.Z. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S4

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Gabriel Wolfson, MS, and Tyler Cromer, MPS, for their thorough review and editing of the manuscript.

Clinical Trial Number and Registry: The clinical trial registry information is included in Table S1.

Funding information

This work was sponsored by Paion.

REFERENCES

- 1. Freyer N, Knöespel F, Damm G, et al. Metabolism of remimazolam in primary human hepatocytes during continuous long‐term infusion in a 3‐D bioreactor system. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antonik LJ, Goldwater DR, Kilpatrick GJ, Tilbrook GS, Borkett KM. A placebo‐ and midazolam‐controlled phase I single ascending‐dose study evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056): Part I. Safety, efficacy, and basic pharmacokinetics. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:274‐283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rex DK, Bhandari R, Desta T, et al. A phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of remimazolam (CNS 7056) compared with placebo and midazolam in patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:427‐437.e426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pastis NJ, Yarmus LB, Schippers F, et al. Safety and efficacy of remimazolam compared with placebo and midazolam for moderate sedation during bronchoscopy. Chest. 2019;155:137‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, et al. Validity and reliability of the Observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation scale: study with intravenous midazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:244‐251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CNS7056‐015 . A study evaluating the safety and efficacy of remimazolam (CNS7056) compared to placebo and midazolam in ASA class III or IV patients undergoing colonoscopy (NCT02532647). 2017.

- 7. Minto CF, Schnider TW, Short TG, et al. Response surface model for anesthetic drug interactions. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1603‐1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loscalzo LM, Wasowski C, Paladini AC, Marder M. Opioid receptors are involved in the sedative and antinociceptive effects of hesperidin as well as in its potentiation with benzodiazepines. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;580:306‐313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vinik HR, Bradley EL Jr, Kissin I. Midazolam‐alfentanil synergism for anesthetic induction in patients. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:213‐217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou J, Leonowens C, Ivaturi VD, et al. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling for remimazolam in the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia in healthy subjects and in surgical subjects. J Clin Anesth. 2020;66:109899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J, Singh H, White PF. Electroencephalographic bispectral index correlates with intraoperative recall and depth of propofol‐induced sedation. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:185‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lacroix BD, Lovern MR, Stockis A, et al. A pharmacodynamic Markov mixed‐effects model for determining the effect of exposure to certolizumab pegol on the ACR20 score in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:387‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doi M. Remimazolam. J Jap Soc Clin Anesth. 2014;34:860‐866. [Google Scholar]

- 14. ONO‐2745IVU007 . An open‐label, single‐dose intravenous administration study to compare the pharmacokinetics and safety of ONO‐2745/CNS 7056 in subjects with chronic hepatic impairment with matching healthy subjects (NCT01790607). 2014.

- 15. Wiltshire HR, Kilpatrick GJ, Tilbrook GS, Borkett KM. A placebo‐and midazolam‐controlled phase I single ascending‐dose study evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056): Part II. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling and simulation. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:284‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schüttler J, Eisenried A, Marco L, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056) after continuous infusion in healthy male volunteers: part I. Pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacodynamics. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:636‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Worthington MT, Antonik LJ, Goldwater DR, et al. A phase Ib, dose‐finding study of multiple doses of remimazolam (CNS 7056) in volunteers undergoing colonoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:1093‐1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pambianco DJ, Borkett KM, Riff DS, et al. A phase IIb study comparing the safety and efficacy of remimazolam and midazolam in patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:984‐992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou J, Curd L, Lohmer LL, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of remimazolam in procedural sedation with nonhomogeneously mixed arterial and venous concentrations. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(1):326‐334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott J, Stanski D. Decreased fentanyl and alfentanil dose requirements with age. A simultaneous pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;240:159‐166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sheiner LB, Stanski DR, Vozeh S, Miller RD, Ham J. Simultaneous modeling of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: application to d‐tubocurarine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;25:358‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wakeling HG, Zimmerman JB, Howell S, Glass PS. Targeting effect compartment or central compartment concentration of propofol: what predicts loss of consciousness? Anesthesiology. 1999;90:92‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koopmans R, Dingemanse J, Danhof M, Horsten GP, van Boxtel CJ. Pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic modeling of midazolam effects on the human central nervous system. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44:14‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou Y, Hu P, Huang Y, et al. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model‐guided dosing optimization of a novel sedative HR7056 in Chinese healthy subjects. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schindler E, Karlsson MO. A minimal continuous‐time Markov pharmacometric model. AAPS J. 2017;19:1424‐1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S4

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3