”Fungi are the interface organisms between life and death.” -- Paul Stamets

Mucormycosis is a potentially lethal, angioinvasive fungal infection predisposed by diabetes mellitus, corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, primary or secondary immunodeficiency, hematological malignancies and hematological stem cell transplantation, solid organ malignancies and solid organ transplantation, iron overload, etc.[1] The increasing incidence of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) in the setting of COVID-19 in India and elsewhere has become a matter of immediate concern.[2,3,4] From the time that we first reported a series of six cases of ROCM in February 2020,[2] there has been an exponential increase in incidence in India, in sync with the soaring second wave of COVD-19.[5,6]

ROCM being a rapidly progressive disease, even a slight delay in the diagnosis or appropriate management can have devastating implications on patient survival.[7] However, the outcome can be optimized by early diagnosis prompted by awareness of warning symptoms and signs and a high index of clinical suspicion, confirmation of diagnosis by appropriate modalities, and initiation of aggressive medical and surgical treatment by a multidisciplinary team.[1,7] This article aims to provide a succinct list of red flags to suspect ROCM, propose a working disease staging system to help choose an appropriate diagnostic modality and tailor therapy, describe an evidence-based management algorithm, and outline possible preventive measures.

Red Flags of ROCM in the Setting of COVID-19

The COVID-19 care teams must be aware of the warning symptoms and signs of ROCM. If a patient currently under active treatment for COVID-19 or on follow-up after completion of treatment exhibits any of the symptoms and signs listed in Table 1, there should be a very high index of suspicion for ROCM, and an immediate ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology consultation is warranted.[1,7] Explanation of early warning signs to patients and the family on discharge following treatment of COVID-19 and a carry-home list of warning symptoms may prompt them to seek early medical attention.

Table 1.

Warning symptoms and signs of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis

| • Nasal stuffiness |

| • Foul smell |

| • Epistaxis |

| • Nasal discharge - mucoid, purulent, blood-tinged or black |

| • Nasal mucosal erythema, inflammation, purple or blue discoloration, white ulcer, ischemia, or eschar |

| • Eyelid, periocular or facial edema |

| • Eyelid, periocular, facial discoloration |

| • Regional pain – orbit, paranasal sinus or dental pain |

| • Facial pain |

| • Worsening headache |

| • Proptosis |

| • Sudden loss of vision |

| • Facial paresthesia, anesthesia |

| • Sudden ptosis |

| • Ocular motility restriction, diplopia |

| • Facial palsy |

| • Fever, altered sensorium, paralysis, focal seizures |

Diagnosis of ROCM

ROCM can be categorized as Possible, Probable, and Proven. A patient who has symptoms and signs of ROCM [Table 1] in the clinical setting of concurrent or recently (<6 weeks) treated COVID-19, diabetes mellitus, use of systemic corticosteroids and tocilizumab, mechanical ventilation, or supplemental oxygen is considered as Possible ROCM. When the clinical symptoms and signs are supported by diagnostic nasal endoscopy findings, or contrast-enhanced MRI or CT Scan, the patient is considered as Probable ROCM. Clinico-radiological features, coupled with microbiological confirmation on direct microscopy or culture or histopathology with special stains or molecular diagnostics are essential to categorize a patient as Proven ROCM. Table 2 lists specifications and criteria for microbiological, histopathological, molecular, and radiological diagnosis of ROCM.

Table 2.

| Diagnostic Technique | Key Diagnostic Features |

|---|---|

| Direct microscopy of the deep or endoscopy-guided nasal swab, paranasal sinus, or orbital tissue, using a KOH mount and calcofluor white is a tool for rapid diagnosis | Non-septate or pauci-septate, irregular, ribbon-like hyphae; Wide-angle of non-dichotomous branching (≥45-90 degree) and greater hyphal diameter as compared to other filamentous fungi. These are 6-25 µm in width. Smears stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori’s methenamine-silver stains can also help in rapid diagnosis. Direct microscopy has about 90% sensitivity. Obtaining the swab from clinically active lesions under endoscopy guidance may help improve the diagnostic yield. |

| Culture of the deep or endoscopy-guided nasal swab, paranasal sinus, or orbital tissue. Brain heart infusion agar, potato dextrose agar or preferably Sabouraud dextrose agar with gentamicin or chloramphenicol and polymyxin-B, but without cycloheximide, incubated at 30-37°C helps in genus and species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing | Rapid growth of fluffy white, gray or brown cotton candy-like colonies. The hyphae are coarse and dotted with brown or black sporangia. It is difficult to distinguish the genera based on the colony morphology and requires a detailed microscopic evaluation. Only about 50% of samples from cases of probable ROCM grow the organism on culture. Obtaining the sample from clinically active parts of the lesion (not from grossly necrotic tissue) may help improve the diagnostic yield. |

| Molecular diagnostics of the tissue sample (deep or endoscopy-guided nasal swab, paranasal sinus, or orbital tissue), culture, or blood | Molecular diagnostic kits are not widely available commercially. There is promising role of quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Molecular diagnostics have about 75% sensitivity and can be used for confirmation of diagnosis where available. |

| Histopathology with Hematoxylin-Eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori’s methenamine-silver special stain. Sample from the nasal mucosa, paranasal sinus mucosa and debris or orbital tissue should be subjected to rapid diagnostic techniques such as frozen section, and squash and imprint, and also processed for routine fixed sections | Hyphae showing tissue invasion is confirmatory of invasive ROCM. Hyphae vary in width from from 10-20 µm in diameter and 6-50 µm in width on histopathology and are non-septate or pauci-septate. In the tissue, hyphae appear ribbon-like with an irregular pattern of branching. There may be pseudo-septae because of folding and the angle of branching may be difficult to appreciate. Wider, irregular, ribbon-like hyphae are more reliable diagnostic features. Histopathology provides diagnostic information in about 80% of samples of probable ROCM. Obtaining the sample from clinically active parts of the lesion (not from grossly necrotic tissue) may help improve the diagnostic yield. |

| Imaging – contrast-enhanced MRI and CT scan. Contrast-enhanced MRI is preferred over CT scan. | Nasal and paranasal sinus mucosal thickening with irregular patchy enhancement is an early sign. Ischemia and non-enhancement of turbinates manifests as an early sentinel sign on MRI – black turbinate sign. The fluid level in the sinus and partial or complete sinus opacification signifies advanced involvement of the paranasal sinuses. Thickening of the medial rectus is an early sign of orbital invasion. Patchy enhancement of the orbital fat, lesion in the area of the superior and inferior orbital fissure and the orbital apex, and bone destruction at the paranasal sinus and orbit indicate advanced disease. Stretching of the optic nerve and tenting of the posterior pole of the eyeball indicate severe inflammatory edema secondary to tissue necrosis. MRI and MR angiography help determine the extent of cavernous sinus involvement and ischemic damage to the CNS. The absence of paranasal sinus involvement has a strong negative predictive value for ROCM. Comparative imaging over time helps monitor the course of the disease. However, radiological resolution lags clinical resolution. |

Staging of ROCM

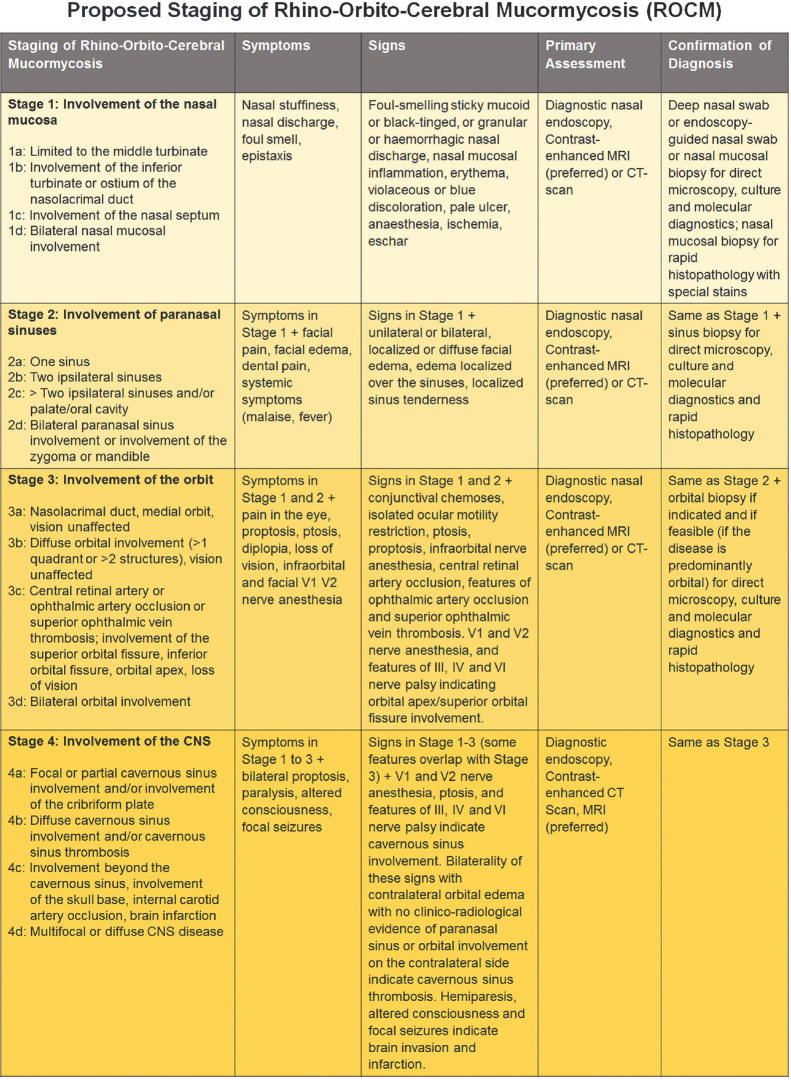

There is no good staging system to categorize the disease severity of ROCM and stratify the diagnostic modalities and management. As the critical care teams start receiving and caring for increasing number of ROCM patients in the setting of COVID-19, a working staging system may help triage these patients and customize their care. The proposed staging system is simple and follows the general anatomical progression of ROCM from the point of entry (nasal mucosa) on to the paranasal sinuses, orbit and brain, and severity in each of these anatomical locations [Fig. 1]. There is an attempt to plug in the symptoms, signs, and preferred diagnostic tools for each of these stages. The next logical step could be to validate it, propose the preferred management for each stage, and then correlate the outcomes.

Figure 1.

Proposed staging of Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis with clinical symptoms and signs, evaluation and diagnosis

Logical Management of ROCM

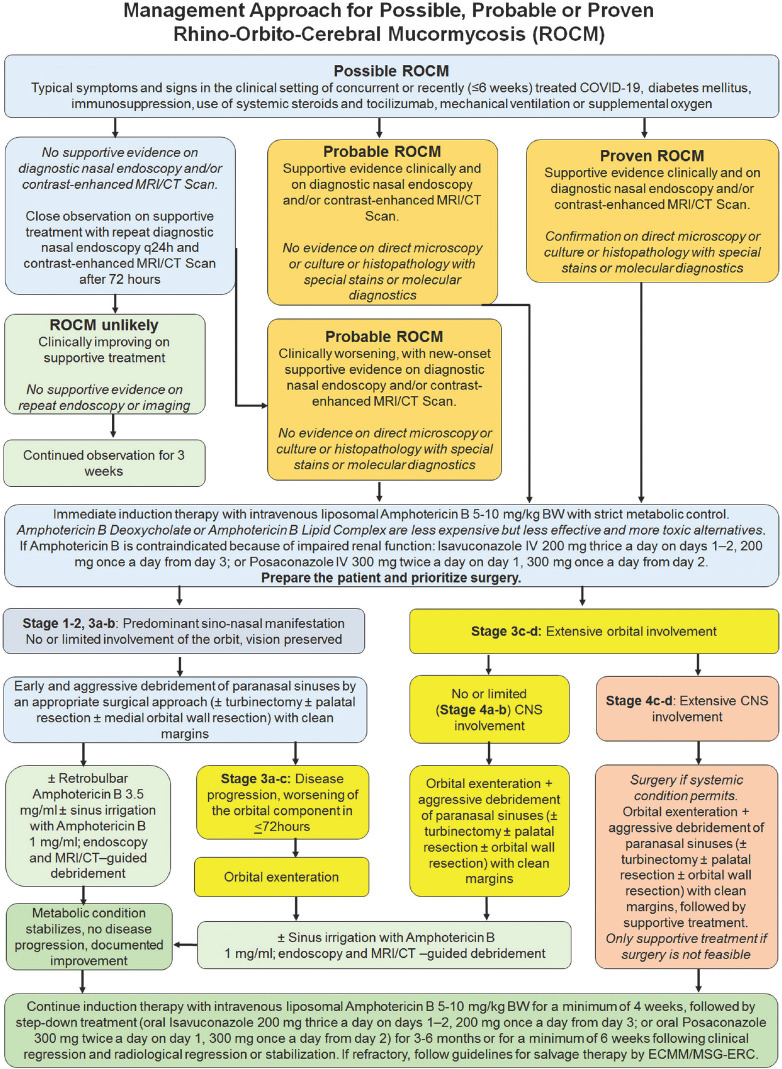

Optimizing the outcome, minimizing the morbidity, and improving the survival in ROCM needs concerted action and rapid response by a multi-disciplinary team comprising of experts in diagnosis (radiology, microbiology, pathology, molecular biology), and medical (infectious disease, neurology, critical care) and surgical (otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology, neurosurgery) care.[7,8] Evidence-based and clear management guidelines help synergize the management within the team. The European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSG ERC) have issued comprehensive management guidelines.[7] Fig. 2 provides diagnostic and management algorithms with salient aspects of the elaborate ECMM-MSG ERC guidelines adapted to standard disease definitions and customized to ROCM in the setting of COVID-19.[7,9] Expeditious clinical or clinico-radiological diagnosis, supported by quick direct microscopy, and induction with full-dose liposomal Amphotericin B is the definitive first step in the long and arduous management of ROCM. In situations with resource-constraint, it may be acceptable to use Amphotericin B Deoxycholate or Amphotericin B Lipid Complex in patients with good renal function. These have relatively lower efficacy and higher systemic toxicity as compared to liposomal Amphotericin B. There is no convincing data to support combination antifungal therapy, and it is not recommended as part of major treatment guidelines.[1,7,8] However, prolonged step-down oral antifungal therapy is warranted.[1,7,8]

Figure 2.

Management algorithm for Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis (ROCM)

Can ROCM be Prevented?

It may be possible to reduce the incidence of ROCM in the setting of COVID-19 by optimizing the indications for systemic corticosteroids, judicious use of tocilizumab, proactive metabolic control, and by minimizing the patient exposure to potential sources of infection [Table 3]. There may be a role for prophylactic oral Posaconazole in high-risk individuals.

Table 3.

Prevention of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis in the setting of COVID-19

| • Judicious and supervised use of systemic corticosteroids in compliance with the current preferred practice guidelines |

| • Judicious and supervised use of tocilizumab in compliance with the current preferred practice guidelines |

| • Aggressive monitoring and control of diabetes mellitus |

| • Strict aseptic precautions while administering oxygen (sterile water for the humidifier, daily change of the sterilized humidifier and the tubes) |

| • Personal and environmental hygiene |

| • Betadine mouth gargle (not nasal drops) |

| • Barrier mask covering the nose and mouth |

| • Consider prophylactic oral Posaconazole in high-risk patients (>3 weeks of mechanical ventilation, >3 weeks of supplemental oxygen, >3 weeks of systemic corticosteroids, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with or without ketoacidosis, prior history of chronic sinusitis, and |

| co-morbidities with immunosuppression) |

Conclusion

Awareness of, and due attention to warning symptoms and signs, and a high index of clinical suspicion, early diagnosis by a diagnostic nasal endoscopy and direct microscopy of the high nasal swab or an endoscopically guided nasal swab, supported by contrast-enhanced MRI or CT scan, initiation of full-dose liposomal Amphotericin B while awaiting the results of culture and histopathology, identification of indications for paranasal sinus surgery and orbital exenteration and meticulous post-surgical management, and continued step-down oral antifungals until clinical and radiologically monitored resolution and beyond, may help optimize the outcome of ROCM in the setting of COVID-19. Inculcating a protocol-based strategy by a multidisciplinary team and a prioritized Code-Mucor approach may be the key to success.

References

- 1.Skied A, Pavleas I, Drogari-Apiranthitou M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of mucormycosis: An update. J Fungi (Basel) 2020;6:265. doi: 10.3390/jof6040265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen M, Lahane S, Lahane TP, Parekh R, Honavar SG. Mucor in a viral land: A tale of two pathogens. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:244–52. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3774_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar S, Gokhale T, Choudhury SS, Deb AK. COVID-19 and orbital mucormycosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1002–4. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3763_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, Sachdev MS. COVID-19 and eye: A review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravani SA, Agrawal GA, Leuva PA, Modi PH, Amin KD. Rise of the phoenix: Mucormycosis in COVID-19 times. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1563–8. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_310_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao R, Shetty AP, Nagesh CP. Orbital infarction syndrome secondary to rhino-orbital mucormycosis in a case of COVID-19: Clinico-radiological features. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;69:1627–30. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1053_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SCA, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: An initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e405–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sipsas NV, Gamaletsou MN, Anastasopoulou A, Kontoyiannis DP. Therapy of mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018;4:90. doi: 10.3390/jof4030090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–21. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]