Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate characteristics of the work environment, job insecurity, and health of marginal part‐time workers (8.0‐14.9 hours/week) compared with full‐time workers (32.0‐40.0 hours/week).

Methods

The study population included employees in the survey Work Environment and Health in Denmark (WEHD) in 2012, 2014, or 2016 (n = 34 960). Survey information from WEHD on work environment and health was linked with register‐based information of exposure based on working hours 3 months prior to the survey, obtained from the register Labour Market Account. Associations between marginal part‐time work and work environment and health were assessed using logistic regression models.

Results

Marginal part‐time workers reported less quantitative job demands, lower levels of influence at work, poorer support from colleagues and leaders, less job satisfaction and poorer safety, as well as more job insecurity. Results on negative social relations in the workplace and physical workload were more ambiguous. Marginal part‐time workers were more likely to report poorer self‐rated health, treatment‐requiring illness, and depressive symptoms compared with full‐time workers. Adjusting for characteristics of the work environment showed an indication of altered odds ratios for self‐rated health and depressive symptoms, whereas job insecurity did not.

Conclusions

This study finds that marginal part‐time workers experience a poorer psychosocial work environment and safety, higher job insecurity, and poorer health than full‐time workers. Work environment characteristics may confound or mediate the association between marginal part‐time work and health. However, prospective studies are needed to determine the causal direction of the revealed associations.

Keywords: full‐time workers, non‐standard work, part‐time workers, precariousness, working hours

1. INTRODUCTION

Marginal part‐time work, characterized by few weekly working hours, 1 , 2 can be a way to meet fluctuations in demands, job creation, or avoid layoffs. 1 , 2 For the employee, it may facilitate a way into or staying connected to the labor market. 1 , 2 Marginal part‐time work has become increasingly widespread since 2008 in Denmark. 3 , 4 , 5 In the Nordic countries, marginal part‐time workers (<15 hours/week) accounted for 4% in Sweden and Finland, 7% Norway, and 15% in Denmark, of all employed in 2015, yet the Danish number may be overestimated and other studies estimate that marginal part‐time account for around 11% in Denmark. 3 Another reason for the variation between the Nordic countries may be related to high percentages of students having marginal part‐time work in Denmark. 3 A large share of marginal part‐time workers in all the Nordic countries are young, 3 women, 3 , 6 , 7 and low‐skilled workers. 3 However, sector variations exist 3 , 5 with marginal part‐time work being most common in wholesale and retail trade, hotels, and restaurants. 3

Previous research suggests that marginal part‐time workers are likely to experience a different work environment than their peers in full‐time positions. 8 A case‐study within Danish retail revealed that systems for the facilitation of information dissemination and critics are mainly aimed at full‐time workers. 9 Thus, employees with part‐time may miss information or feedback if they are not included in these systems. Studies have also found less job variety, 10 learning opportunities, 11 and complex tasks 12 among marginal part‐time workers. Moreover, marginal part‐time work may include employment instability, lack of power, rights, and poor terms, 13 as well as higher levels of job or income insecurity. 3 , 14 Several work environment characteristics 15 , 16 , 17 and job insecurity 18 , 19 have been associated with poor mental 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 and somatic health. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Thus, marginal part‐time workers may experience a less supportive work environment and higher levels of job insecurity, which may influence their health negatively, compared to full‐time‐workers.

Only a few studies have addressed characteristics of the work environment 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 20 and health 7 , 20 , 21 among marginal part‐time workers and some characteristics of the work environment, for example, arguments and conflicts, seem to remain unstudied. Results from the few studies are not consistent, but generally show a poorer work environment, 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 while results on health are more deviating. 7 , 20 , 21 Thus, previous findings are not conclusive and may be context‐specific. In addition, studies have used self‐reported data of both exposure and outcome, 7 , 11 , 20 , 21 which may give rise to information bias. Therefore, this study aimed to assess if marginal part‐time workers (8.0‐14.9 hours/week) have a poorer work environment, experience higher job insecurity, and poorer health than full‐time workers (32.0‐40.0 hours/week) by using Danish register‐based information on exposure.

2. METHOD

2.1. Data

This study links exposure information from The Labour Market Account without standardization of hours (LMA) 22 with outcomes in the Work Environment and Health in Denmark (WEHD) survey, 23 and covariates from Statistics Denmark's population registers. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27

The LMA 22 is a unique Danish register with administrative data of labor market status since 2008. 22 It is based on information from several registers, including the e‐income register from The Danish Tax Agency with employer‐registered information on all paid jobs of all Danish citizens. 22 , 28 The register covers the total Danish population and less than 4% (in 2013) of (paid) working hours in the register are imputed due to missing or invalid information. 28 Thus, LMA is considered to be of high quality. 22 , 28

The WEHD survey was established for governmental use to monitor the work environment and health among Danish employees. 29 It was sent out every second year between 2012 and 2018 to a sample of employees aged 18‐69 years old who lived in Denmark, worked at least 35 hours per month, and had an income of at least 3000 Danish Kroner per month (approximately 400 EUR). 29 The WEHD survey was sent to more than 50 000 employees in each wave (2012: n = 50 806; 2014: n = 50 875; 2016: n = 65 741) and response rates were above 50% (2012: 51.5%, 2014: 57.3%, 2016: 52.9%). 23 Fewer men, young employees, and employees with low socioeconomic status (SES) participated, which is similar to what has been reported in previous similar surveys. 29

Finally, we used population register information from Statistics Denmark, including The Danish Civil Registration System, 24 The Population Education Register, 25 The Income Statistics Register, 26 and The Employment Classification Module. 27

2.2. Study population

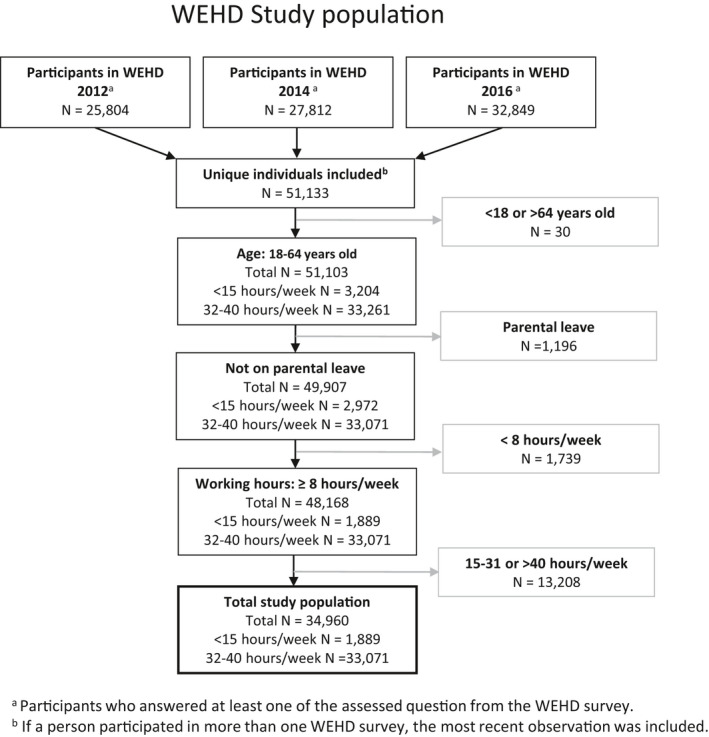

We included all respondents of the WEHD in 2012, 2014, or 2016, who were between 18 and 64 years old, not on maternity leave and had at least 8 hours of work/week on average in the 3 months prior to answering the questionnaire. Employees who responded to more than one questionnaire were included with their most recent questionnaire response. The study population included 34 960 unique individuals with 8 to <15 or 32‐40 hours of work/week (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study population

2.3. Comparison with the Danish source population

To analyse whether the study population was representative of the source population, we used information from the total working population in Denmark (n = 1,841,566) from the LMA 22 with the same inclusion criteria as for the study population (see Figure S1 for flow chart). We assessed demographic characteristics of the participants in the study population and the source population (see Table S1) as well as the association between participation in WEHD and marginal part‐time work (see Table S2). A smaller share of marginal part‐time workers, compared with full‐time workers, participated in the survey (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.55‐0.65). This difference was reduced after adjustment for gender, age, and SES (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.71‐0.86). Thus, analyses were presented in a crude model and model 1 adjusted for gender, age, and SES.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Marginal part‐time work

Data on marginal part‐time work were obtained from the LMA based on information on working hours (from salaried employees, self‐employed, and co‐working spouses). Each employees’ average number of weekly working hours, across the three months prior to the WEHD response date, was calculated. Marginal part‐time work was defined as 8.0‐14.9 hours work/week, based on previously used definitions of marginal part‐time as <15 hours/week. 3 The lower cut was applied as WEHD only included employees with an average of at least 8 hours of work per week (35 hours/month). In Denmark, the norm for full‐time work is 37 hours per week and a 5‐day workweek. Thus, we used full‐time work, defined as 32.0‐40.0 hours per week on average for the past three months, as the reference group.

2.4.2. Demographic characteristics

Based on existing literature, a number of covariates were included. We used information from the LMA on gender, age (in 10‐year intervals), sector (categorized by the Danish work sector code2007 [DB07]), job (based on Statistics Denmark's Danish International Standard Classification of Occupations, revision 2008 [DISCO‐08] codes and categorized by the first digit), and social benefits (pension, student, sickness, and flex [subsidized job], see Table S5 for codes). Information on the region of residence and marital status (categorized as a partner [married or registered partnership] or no partner [all others]) was obtained from The Danish Civil Registration System. Education level was obtained from The Population Education Register 25 with information on the highest obtained level of education (categorized using the Danish International Standard Classification of Education, see Table S6 for codes). Income was obtained from The Income Statistics Register 26 and presented as percentiles (p) (low [<p25], intermediate [p25‐p75], and high [>p75]). SES was obtained from The Employment Classification Module 27 based on information on the individual's most important source of income or work (see Table S7 for codes).

2.4.3. Outcomes

We studied psychosocial work environment characteristics (quantitative job demands, influence at work, support from colleagues and leaders, negative social relations, and job satisfaction), physical workload, safety, job insecurity, and health characteristics based on questions from the WEHD survey. See Appendix S8 for the included survey questions and the categorizations of response categories.

2.4.4. Work environment characteristics

The psychosocial characteristics included quantitative job demands (not having enough time for work tasks, availability outside of normal work hours, and struggling to meet deadlines) categorized as high or low; influence at work (influence on how and when to solve work tasks and sufficient authority) categorized as low or high; support from colleagues and leaders (leader feedback on work, acknowledgement from management, acknowledgement among colleagues and help among colleagues) categorized as poor or good; negative social relations (involvement in arguments or conflicts, exposed to bullying and physical violence or threats of violence at the workplace in the previous 12 months) categorized as yes or none; and job satisfaction (interesting and inspiring work tasks, and overall job satisfaction) categorized as low or high. The physical characteristics included physical workload (how physically hard workers perceived the work) categorized as hard or not hard; and physical work demands (based on an index score of how much of the time workers sat, walked or stood, worked with back twisted, arms lifted, had repetitive arm movements, squatting or kneeling, pushing or pulling and lifting) categorized as low or high. Lastly, safety characteristics included occupational accidents (occupational accidents the past year resulting in more than one day's absence) categorized as yes or none; and safety instruction (receiving the necessary guidance and instruction to work safely) categorized as poor or good.

2.4.5. Job insecurity

Job insecurity (worrying about becoming unemployed and worrying about being transferred) was categorized as high or low.

2.4.6. Health characteristics

Self‐rated health was categorized as poor or good. Treatment‐requiring illness the past year comprised of 11 questions (on depression, asthma, diabetes, atherosclerosis or heart attack, cerebral thrombosis, eczema, cancer, hearing loss, back disease, migraine, or other long‐term illness) and categorized as any or none. Pain (pain within the last 3 months) was categorized as pain or no pain. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Major Depressive Inventory (MDI) 30 and categorized as no or depressive symptoms (MDI≥20). Stress (feelings of stress the past 2 weeks) was categorized as stress or no stress, and finally, sleep disturbance (frequent awakenings with difficulties falling asleep again or not feeling rested in the past 4 weeks) was categorized as high or low.

2.5. Data analysis

We use the unique Danish identification number and the WEHD response date to link the exposure to the outcomes on an individual level. Associations between marginal part‐time work and work environment, job insecurity, and health outcomes were assessed by logistic regression. We used full‐time workers (32‐40 hours/week) as the reference in all analyses. Results on the association between marginal part‐time and work environment, job insecurity, and health (Tables 2 and 3), are presented in a crude model without any adjustment and in model 1 including adjustment for age, gender, and SES (plus treatment‐requiring illness in results on health outcomes). To assess if work environment or job insecurity explained some of the association between marginal part‐time work and the health outcomes, in Table 4, we adjusted the associations between marginal part‐time work and the health outcomes for model 1 and quantitative job demands, influence at work, support from colleagues and leaders, negative social relations, job satisfaction, physical workload, safety, and job insecurity, respectively. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are presented and all analyses were performed in SAS 9.4.

TABLE 2.

Work environment characteristics and job insecurity among marginal part‐time workers compared with full‐time workers (n = 34 960)

| 8 to <15 hours/week | 32‐40 hours/week (reference) | Crude | Model 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Quantitative job demands (high) | ||||||||||

| Not enough time | 179 | 12.4 | 6460 | 20.2 | 0.56 | 0.49‐0.66 | <.001 | 0.81 | 0.67‐0.97 | .021 |

| Available outside work hours | 512 | 35.6 | 13 040 | 40.7 | 0.81 | 0.72‐0.90 | <.001 | 0.88 | 0.77‐1.01 | .065 |

| Hard to keep deadlines | 360 | 25.0 | 11 870 | 37.1 | 0.57 | 0.50‐0.64 | <.001 | 0.79 | 0.69‐0.91 | .001 |

| Influence at work (low) | ||||||||||

| Influence on how to solve work tasks | 84 | 5.8 | 630 | 2.0 | 3.07 | 2.43‐3.88 | <.001 | 2.18 | 1.61‐2.94 | <.001 |

| Influence on when to solve work tasks | 188 | 12.9 | 2282 | 7.1 | 1.95 | 1.66‐2.28 | <.001 | 1.54 | 1.26‐1.88 | <.001 |

| Sufficient authority | 174 | 12.1 | 2208 | 7.0 | 1.84 | 1.56‐2.17 | <.001 | 1.37 | 1.12‐1.69 | .002 |

| Support from colleagues and leaders (poor) | ||||||||||

| Leader feedback | 386 | 26.9 | 8577 | 27.1 | 0.99 | 0.88‐1.11 | .853 | 1.19 | 1.03‐1.38 | .016 |

| Work acknowledgement from management | 336 | 23.4 | 7586 | 24.0 | 0.97 | 0.86‐1.10 | .630 | 1.07 | 0.92‐1.24 | .403 |

| Acknowledgement of work between colleagues | 71 | 4.9 | 1021 | 3.2 | 1.57 | 1.23‐2.01 | <.001 | 1.36 | 1.01‐1.84 | .046 |

| Help between colleagues | 54 | 3.7 | 759 | 2.4 | 1.60 | 1.20‐2.11 | .001 | 1.67 | 1.20‐2.34 | .003 |

| Negative social relations in the workplace (yes) | ||||||||||

| Arguments or conflicts | 617 | 42.9 | 18 566 | 58.1 | 0.54 | 0.49‐0.60 | <.001 | 0.71 | 0.62‐0.81 | <.001 |

| Bullying | 168 | 11.7 | 3625 | 11.3 | 1.04 | 0.88‐1.22 | .666 | 1.07 | 0.88‐1.30 | .514 |

| Threats or violence | 148 | 10.3 | 3190 | 10.0 | 1.04 | 0.87‐1.24 | .683 | 1.11 | 0.90‐1.38 | .323 |

| Job satisfaction (low) | ||||||||||

| Interesting work tasks | 266 | 18.4 | 1818 | 5.7 | 3.75 | 3.25‐4.32 | <.001 | 1.83 | 1.52‐2.21 | <.001 |

| General job satisfaction a | 76 | 8.2 | 1160 | 5.5 | 1.54 | 1.21‐1.96 | .001 | 1.87 | 1.40‐2.49 | <.001 |

| Physical workload | ||||||||||

| Hard physical work (hard) | 180 | 14.8 | 2931 | 13.1 | 1.15 | 0.98‐1.36 | .084 | 1.08 | 0.89‐1.31 | .429 |

| Physical work demands (high) | 596 | 31.6 | 6560 | 19.8 | 1.86 | 1.68‐2.06 | <.001 | 0.87 | 0.76‐0.99 | .035 |

| Safety | ||||||||||

| Occupational accidents (yes) | 106 | 7.4 | 1728 | 5.4 | 1.40 | 1.14‐1.71 | .001 | 1.31 | 1.03‐1.68 | .028 |

| Safety instruction (poor) | 218 | 18.2 | 3370 | 13.0 | 1.49 | 1.28‐1.74 | <.001 | 1.32 | 1.10‐1.59 | .003 |

| Job insecurity (high) | ||||||||||

| Worry of unemployment | 252 | 16.7 | 3686 | 11.3 | 1.57 | 1.37‐1.81 | <.001 | 1.51 | 1.27‐1.79 | <.001 |

| Worry of transfer | 141 | 9.5 | 2533 | 7.8 | 1.23 | 1.03‐1.47 | .024 | 1.67 | 1.36‐2.05 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval.

Reference group: 32‐40 hours/week. Model 1: Adjusted for gender, age, and SES.

%: The percentage of workers reporting the outcome within marginal part‐time workers and full‐time workers.

General job satisfaction was not part of the 2012 questionnaire.

TABLE 3.

Health characteristics of marginal part‐time workers compared with full‐time workers (n = 34 960)

| 8 to <15 hours/week | 32‐40 hours/week (reference) | Crude | Model 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Poor self‐rated health | 253 | 17.7 | 2402 | 7.5 | 2.65 | 2.30‐3.05 | <.001 | 3.05 | 2.55‐3.64 | <.001 |

| Treatment‐requiring illness | 647 | 45.8 | 11 205 | 35.4 | 1.54 | 1.39‐1.72 | <.001 | 1.98 | 1.73‐2.26 | <.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 281 | 21.0 | 3119 | 10.8 | 2.19 | 1.91‐2.51 | <.001 | 1.72 | 1.45‐2.05 | <.001 |

| Stress | 274 | 19.2 | 4684 | 14.7 | 1.38 | 1.20‐1.58 | <.001 | 1.19 | 1.00‐1.41 | .048 |

| High sleep disturbance | 647 | 45.2 | 12 748 | 40.0 | 1.24 | 1.12‐1.38 | <.001 | 1.12 | 0.98‐1.27 | .099 |

| Pain | 1123 | 78.4 | 24 265 | 76.1 | 1.14 | 1.00‐1.30 | .047 | 1.13 | 0.96‐1.33 | .156 |

Reference group: 32‐40 hours/week. Model 1: adjusted for gender, age, SES, and treatment‐requiring illness (not in the outcome: treatment‐requiring illness).

%: The percentage of workers reporting the outcome within marginal part‐time workers and full‐time workers.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

TABLE 4.

Health characteristics of marginal part‐time workers compared with full‐time workers adjusted for gender, age, SES, treatment‐requiring illness, and the different work environment characteristics (n = 34 960)

| 8 to <15 vs 32‐40 hours/week (reference) | Poor self‐rated health | Treatment‐requiring illness | Depressive symptoms | Stress | High sleep disturbance | Pain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Model 2 | 3.05 | 2.55‐3.64 | 1.98 | 1.73‐2.26 | 1.72 | 1.45‐2.05 | 1.19 | 1.00‐1.41 | 1.12 | 0.98‐1.27 | 1.13 | 0.96‐1.33 |

| Model 2 + Quantitative job demands a | 3.21 | 2.68‐3.84 | 2.03 | 1.77‐2.32 | 1.88 | 1.57‐2.24 | 1.37 | 1.15‐1.65 | 1.16 | 1.02‐1.32 | 1.14 | 0.96‐1.35 |

| Model 2 + Influence at work b | 3.04 | 2.53‐3.65 | 1.93 | 1.68‐2.22 | 1.68 | 1.40‐2.01 | 1.16 | 0.98‐1.39 | 1.10 | 0.96‐1.26 | 1.14 | 0.96‐1.35 |

| Model 2 + Interpersonal relationships and leadership c | 3.19 | 2.65‐3.84 | 1.97 | 1.72‐2.26 | 1.79 | 1.49‐2.14 | 1.21 | 1.02‐1.44 | 1.12 | 0.98‐1.29 | 1.16 | 0.97‐1.38 |

| Model 2 + Negative social relations d | 3.28 | 2.73‐3.93 | 2.04 | 1.78‐2.34 | 1.89 | 1.58‐2.26 | 1.26 | 1.06‐1.50 | 1.16 | 1.01‐1.32 | 1.16 | 0.98‐1.37 |

| Model 2 + Job satisfaction e | 3.36 | 2.70‐4.19 | 1.96 | 1.66‐2.31 | 1.73 | 1.39‐2.15 | 1.16 | 0.94‐1.44 | 1.08 | 0.92‐1.27 | 1.16 | 0.95‐1.43 |

| Model 2 + Physical workload f | 2.51 | 2.06‐3.06 | 1.94 | 1.67‐2.24 | 1.68 | 1.39‐2.03 | 1.14 | 0.95‐1.38 | 1.08 | 0.94‐1.25 | 1.06 | 0.87‐1.29 |

| Model 2 + Safety g | 2.84 | 2.33‐3.46 | 2.00 | 1.73‐2.32 | 1.76 | 1.45‐2.12 | 1.18 | 0.98‐1.42 | 1.15 | 0.99‐1.32 | 1.08 | 0.89‐1.30 |

| Model 2 + All work environment h | 2.87 | 2.20‐3.74 | 2.02 | 1.66‐2.46 | 1.91 | 1.47‐2.49 | 1.35 | 1.04‐1.77 | 1.08 | 0.89‐1.30 | 1.22 | 0.93‐1.61 |

| Model 2 + Job insecurity i | 2.98 | 2.48‐3.58 | 1.93 | 1.68‐2.21 | 1.62 | 1.35‐1.94 | 1.13 | 0.95‐1.34 | 1.10 | 0.96‐1.25 | 1.11 | 0.94‐1.32 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Reference group: 32‐40 hours/week. Model 2: adjusted for gender, age, SES, and treatment‐requiring illness.

Adjusted for: Not enough time, available outside work hours, and hard to keep deadlines.

Adjusted for: Influence on how to solve work tasks, influence on when to solve work tasks and sufficient authority.

Adjusted for: Leader feedback, work acknowledgement from management, acknowledgement of work between colleagues, and help between colleagues.

Adjusted for: Arguments or conflicts, bullying and threats or violence.

Adjusted for: Interesting work tasks and general job satisfaction.

Adjusted for: Hard physical work and physical work demands.

Adjusted for: Safety, occupational accidents, and safety instruction.

Adjusted for: Quantitative job demands, influence at work, support from colleagues and leaders, negative social relations, job satisfaction, physical workload, and safety.

Adjusted for: Worry of unemployment and worry of transfer.

2.5.1. Supplementary analyses

In previous studies, a large proportion of Danish marginal part‐time workers reported education or training as a reason for working reduced hours (85%). 3 Students may differ from other marginal part‐time workers in their work environment, job insecurity, and health. Thus, we conducted supplementary analyses of the work environment, job insecurity, and health excluding participants receiving student allowances, that is, a monthly public support scheme provided to all students regardless of parent's income in Denmark.

3. RESULTS

The WEHD study population had a mean age of 45.4 years, and 51% were women. Compared with full‐time workers, marginal part‐time workers were younger, more often women, had lower educational attainment and lower income, fewer had a partner and children, and they more often received social benefits from a pension, student allowances, sick pay or flex (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of (n = 34 960) participants from the Work Environment and Health in Denmark (WEHD) in 2012, 2014, and 2016

| 8 to <15 hours /week | 32‐40 hours/week | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1889 | 33 071 | ||

| n | % | N | % | |

| Age | ||||

| 18‐24 | 744 | 39 | 1129 | 3 |

| 25‐34 | 294 | 16 | 4347 | 13 |

| 35‐44 | 195 | 10 | 8186 | 25 |

| 45‐54 | 310 | 16 | 11 005 | 33 |

| 55‐64 | 346 | 18 | 8404 | 25 |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 1155 | 61 | 16 811 | 51 |

| Region | ||||

| North Jutland | 170 | 9 | 3086 | 9 |

| Central Jutland | 408 | 22 | 7491 | 23 |

| Southern Denmark | 411 | 22 | 7112 | 22 |

| Capital | 708 | 37 | 10 939 | 33 |

| Zealand | 192 | 10 | 4443 | 13 |

| Sector | ||||

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 38 | 2 | 347 | 1 |

| Manufacturing, quarrying and supply | 107 | 6 | 4686 | 14 |

| Construction | 73 | 4 | 1331 | 4 |

| Transportation and trading etc | 642 | 34 | 5959 | 18 |

| Information and communication | 58 | 3 | 1399 | 4 |

| Finance and insurance | 32 | 2 | 1398 | 4 |

| Real estate activities | <20 | <1 | 485 | 1 |

| Professional service activities | 201 | 11 | 3156 | 10 |

| Public administration, education & health | 586 | 31 | 12 913 | 39 |

| Culture, recreation and other | 130 | 7 | 1395 | 4 |

| Missing | <20 | <1 | <20 | <1 |

| Job | ||||

| Managers | 31 | 2 | 1992 | 6 |

| Professionals | 309 | 16 | 11 537 | 35 |

| Technicians and associate professionals | 104 | 6 | 5022 | 15 |

| Clerical support workers | 238 | 13 | 3149 | 10 |

| Services and sales workers | 619 | 33 | 3904 | 12 |

| Skilled agricultural, forestry & fishery workers | <20 | <1 | 158 | 0 |

| Craft and related trades workers | 85 | 5 | 2404 | 7 |

| Plant and machine operators & assemblers | 57 | 3 | 1457 | 4 |

| Elementary occupations | 245 | 13 | 1806 | 5 |

| Armed forces occupations | <20 | <1 | 316 | 1 |

| Missing | 174 | 9 | 1326 | 4 |

| Highest attained education | ||||

| Primary | 555 | 29 | 4038 | 12 |

| Secondary | 941 | 50 | 15 943 | 48 |

| Higher | 347 | 18 | 12 722 | 38 |

| Missing | 46 | 2 | 368 | 1 |

| Income | ||||

| Low | 1,403 | 74 | 5516 | 17 |

| Intermediate | 395 | 21 | 17 554 | 53 |

| High | 91 | 5 | 10 001 | 30 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Self‐employed | <20 | <1 | 51 | 0 |

| Ground level salaried employed | 375 | 20 | 10 271 | 31 |

| Mid‐level salaried employed | 158 | 8 | 8463 | 26 |

| High level salaried employed | 113 | 6 | 9572 | 29 |

| Other salaried employed | 315 | 17 | 4176 | 13 |

| Public income supported | 150 | 8 | 199 | 1 |

| Students | 767 | 41 | 339 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Partner | 619 | 33 | 20 577 | 62 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | <20 | <1 |

| Children living at home | ||||

| Yes | 781 | 41 | 17 458 | 53 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | <20 | <1 |

| Social benefits a | ||||

| Pension | 135 | 7 | 240 | 1 |

| Student | 805 | 43 | 59 | 0 |

| Sickness | 367 | 20 | 613 | 2 |

| Flex | 198 | 10 | 24 | 0 |

| Questionnaire year | ||||

| 2012 | 657 | 35 | 10 884 | 33 |

| 2014 | 563 | 30 | 11 803 | 36 |

| 2016 | 669 | 35 | 10 384 | 31 |

Individuals can be present in more than one benefit category (pension, student, sickness, flex).

3.1. Marginal part‐time work and work environment

In Table 2, after adjusting for age, gender, and SES results on quantitative work demands show that marginal part‐time workers less often report too little time for their work tasks (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67‐0.97) and that they struggle to keep deadlines (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69‐0.91), compared with full‐time workers. We also observed an indication of marginal part‐time workers being less available outside normal work hours (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.77‐1.01). Concerning influence at work, OR of low influence on how and when to solve work tasks and low authority was 2.18 (95% CI 1.61‐2.94), 1.54 (95% CI 1.26‐1.88) and 1.37 (95% CI 1.12‐1.69) for marginal part‐time work, respectively. In terms of support from colleagues and leaders, marginal part‐time workers more often reported rare or no feedback (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.03‐1.38), poorer degree of acknowledgement (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.01‐1.84), and help (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.20‐2.34) from colleagues, but not less acknowledgement from the management. We observed no clear associations between marginal part‐time work and bullying and violence or threats, yet marginal part‐time workers were less likely to report conflicts (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.62‐0.81). Moreover, marginal part‐time workers more often reported low job satisfaction (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.40‐2.49) and a low degree of interesting and inspiring work tasks (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.52‐2.21). Results on physical workload were less clear, and we observed lower reports of a perceived hard physical work among marginal part‐time workers (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76‐0.99), but not lower physical work demands. Regarding safety at work, marginal part‐time workers more often reported experiencing an occupational accident within the past year (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.03‐1.68) and poor guidance and instructions to work safely (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.10‐1.59).

Marginal part‐time workers reported higher job insecurity, with a higher degree of worrying about unemployment (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.27‐1.79) and transference (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.36‐2.05), compared with full‐time workers.

As shown in Table 3, marginal part‐time workers had higher odds of poor self‐rated health (OR 3.05, 95% CI 2.55‐3.64), treatment‐requiring illness (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.73‐2.26) and depressive symptoms (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.45‐2.05) after adjustment for age, gender, SES and treatment‐requiring illness. Our results also indicated that marginal part‐time workers reported a higher degree of stress (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.00‐1.41), sleep disturbances (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98‐1.27), and pain (1.13 95% CI 0.96‐1.33), though not statistically significant. When the analyses were adjusted for work environment characteristics (Table 4), OR of treatment‐requiring illness, sleep disturbance, and pain remained stable. The OR for poor self‐rated health increased after adjustment for several psychosocial work environment characteristics. Conversely, physical workload and safety attenuated the OR of self‐rated health. The estimate for depressive symptoms was elevated after adjustment for quantitative job demands and negative social relations. OR for stress, was elevated after adjusting for quantitative job demands. Adjusting for job insecurity did not appear to alter the OR for health.

Excluding students in the supplementary analyses, generally increased the OR, but did not change the main conclusions (see Tables S3 and S4), except for physical workload, which showed higher odds of hard physical work in marginal part‐time workers (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.06‐1.60). In particular, OR were enlarged for occupational accidents, worry of unemployment and hard physical work as well as poor self‐rated health and treatment‐requiring illness.

4. DISCUSSION

This study finds that marginal part‐time workers report less quantitative job demands, lower levels of influence at work, poorer support from colleagues and leaders, less job satisfaction, poorer safety, and higher levels of job insecurity compared with full‐time workers. We found no clear associations between marginal part‐time work and negative social relations and physical workload. In addition, marginal part‐time workers generally reported poorer health than full‐time workers, particularly for self‐rated health, treatment‐requiring illness, and depressive symptoms. Our findings indicate that characteristics of the work environment to some degree altered the estimates for poor self‐rated health and depressive symptoms, while the other health characteristics remained more stable. Job insecurity did not alter the OR for health.

4.1. Marginal part‐time work and work environment

Our findings on the work environment extend the evidence and are generally in line with the few previous studies on populations from Scandinavia and the Netherlands. These studies also found lower quantitative job demands, 7 , 10 poorer influence at work, 7 , 10 and poorer safety 31 among marginal part‐time workers compared with full‐time workers. Our findings on job satisfaction are also in line with some previous findings on less interesting work tasks, 10 , 11 , 12 yet other studies also showed no association or higher job satisfaction. 7 , 11 , 32 We only identified one study on support from colleagues and leaders, 7 which indicated no association between marginal part‐time work and assistance from colleagues. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have assessed marginal part‐time work and negative social relations or physically demanding work.

Low quantitative job demands combined with low influence at work, place marginal part‐time workers as passive employees according to the Job Demand Control Model by Robert Karasek. 33 Being a passive employee can result in dissatisfying jobs, 33 in line with our findings on job satisfaction. There may well be a dualism in part‐time work, where some people choose voluntarily to work part‐time, for example, for a better work‐life balance, while others are forced into part‐time work if they cannot find a permanent full‐time job. 34 Working fewer hours or more hours than desired has been related to job dissatisfaction. 35 Thus, our finding of lower job satisfaction among marginal part‐time workers could be related to the marginal part‐time work being involuntary, though studies suggest that only a small fraction (5%) of marginal part‐time work in Denmark is involuntary. 36 In terms of physical workload, our findings were ambiguous and need further exploration. Reports of occupational accidents were higher among marginal part‐time workers and the estimate increased after excluding students. Considering the fewer hours of work among marginal part‐time workers, the actual risk of an accident per hour of work is expected to be even higher for marginal part‐time workers.

4.2. Marginal part‐time work and job insecurity

Our findings on higher job insecurity among marginal part‐time workers are in line with findings from other Nordic countries. 3 Yet, previous results on Danish marginal part‐time workers suggested lower job insecurity among marginal part‐time workers compared with full‐time workers. 3 This discrepancy in the findings from the Danish studies is likely related to the different questions on job insecurity used, which in the previous study also includes unemployment 1 year earlier.

4.3. Marginal part‐time work and health

Our findings of poorer health among marginal part‐time workers are in line with a British longitudinal study that indicated a higher risk of poor perceived health among marginal part‐time workers without a permanent contract compared with permanent full‐time works. 21 However, the association may be context‐specific as this result was not reproduced in a German population. 21 The high OR in self‐rated health, treatment‐requiring illness, and depressive symptoms indicate that marginal part‐time is more strongly related to long‐term health characteristics compared to the more acute symptoms like stress, sleep, and pain.

Findings in this study suggest an accumulation of unfavorable characteristics of the work environment and health among marginal part‐time workers. Precarious employment 6 is a multidimensional construct with an accumulation of unfavorable aspects of employment quality. 13 , 14 No universal definition of this concept exists and both ‘atypical’ and ‘nonstandard’ (which may cover marginal part‐time) are widely used. A recent theoretical framework of precarious employment, 13 suggested that precarious employment may result in poor health and quality of life through a poorer work environment and material deprivation, also suggested as potential mechanisms by other studies. 4 , 37 A mediating effect by work environment characteristics between marginal part‐time work and health has also been observed in some previous studies, 38 , 39 although other cross‐sectional studies reported that marginal part‐time workers themselves less often felt their health was affected by their work. 7 , 20 Our results indicated that several characteristics of the work environment altered the estimates of marginal part‐time on self‐rated health and depressive symptoms and therefore may confound or mediate the association. Due to the cross‐sectional design of the present study reverse causation cannot be ruled out and prospective studies are needed to determine the direction of the revealed associations.

The supplementary analyses indicated higher experience of job insecurity in marginal part‐time workers after excluding students, that is, students experience less job insecurity. This may be related to a transitional process of students, who may take on marginal part‐time jobs voluntarily during their studies. 8 The supplementary results also indicated that students reported less poor work environment characteristics and better health. Previous studies have not conducted separate analyses on students. Yet, our findings suggest separating the effects of students in future studies.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

One strength of this study is the relatively large study population with employees from different sectors and jobs. Another strength is that we assessed the possible selection bias from participation by use of register information for all working individuals living in Denmark. Given the moderate WEHD response rate, our sample may not be representative of all Danish employees and survey participation among marginal part‐time workers indicated some degree of selection compared to full‐time workers. Thus, there is a risk of selection bias from conditioning on a common effect (participation in WEHD) if work environment or health characteristics are also associated with participation. However, adjustment for age, gender, SES, and previous illness (in health outcomes) limited the possible bias. Furthermore, the use of self‐reported data is necessary for the assessment of several work environment and health characteristics, which are not found in registers. Register‐based information of the exposure reduced the risk of bias from self‐reporting. Yet, unpaid and undeclared work hours may exist. 40 Thus, some marginal part‐time workers may work more hours than registered. In addition, the WEHD survey did not include marginal part‐time workers with less than 8 hours of work per week. We expect this may have reduced some of the effects and therefore consider our results to be conservative.

The use of exposures 3 months prior in time to the survey outcomes, is another strength as the exposure is known to be present prior to the survey response. However, reverse causality can still be a problem, in particular in relation to the health outcomes. Another possible issue is a healthy worker effect due to a selection into marginal part‐time work and/or out of full‐time work among people with health issues. Marginal part‐time workers may include vulnerable workers, unable to work full‐time, for example, due to health issues. However, our results on health were not explained by treatment‐requiring illnesses in the past year. Thus, chronic diseases cannot solely explain the poorer health found among marginal part‐time workers, yet additional diagnosed or undiagnosed health issues may still be present.

The generalizability of these findings may be limited to other Nordic countries, with somewhat similar labor market flexibility and welfare states. The policy context (eg collective agreements) and social context (eg education level and social support), may modify the effect of marginal part‐time work on health. 7 , 13 , 21 Also, the type of marginal part‐time work (eg fixed term contracts or involuntariness) may confound or modify the effects of marginal part‐time work on work environment and health. Thus, distinguishing between different types of marginal part‐time workers may be valuable in future studies. Finally, given the high proportion of women in marginal part‐time work, future studies may explore if the association with the work environment, job insecurity and health differ by gender.

In conclusion, our findings show that marginal part‐time workers have a poorer psychosocial work environment and safety, more job insecurity and poorer health than full‐time workers, which is not explained by age, gender, SES, and treatment‐requiring illness (in health outcomes). Characteristics of the work environment may confound or mediate the association with health outcomes. These results suggest that marginal part‐time workers are a vulnerable group of workers with an accumulation of unfavorable characteristics of the work environment and health. Prospective studies are needed to determine the direction of the revealed associations between marginal part‐time work and work environment and health along with any potential mediating effect of work environment on health.

DISCLOSURES

Ethics approval: The WEHD survey was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. The WEHD is registered by The Danish Data Protection Agency (2015‐57‐0074, NRCWE journal number 2013‐10‐11). Informed consent: Participants were informed about the purpose of the WEHD and by returning the questionnaire, the participants consented to participate. Registry and the Registration No. of the study/Trial: N/A. Animal Studies: N/A. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the design of the study. HBN, LSG, and K.P analysed the data and HBN led the writing. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank all the participants in the WEHD and the WEHD coordination group from National Research Centre for the Working Environment (NRCWE), Denmark.

Nielsen HB, Gregersen LS, Bach ES, et al. A comparison of work environment, job insecurity, and health between marginal part‐time workers and full‐time workers in Denmark using pooled register data. J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12251. 10.1002/1348-9585.12251

Funding information

This project is funded by The Velliv Association (Velliv Foreningen). The Velliv Association took no part in the design, the analyses, the preparation of the manuscript or decision to publish this manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This study is based on anonymized micro data available from Statistics Denmark. Access to data can only be permitted through an affiliation with a Danish authorized environment. For further information on data and data access please see www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Messenger J, Wallot P. The Diversity of 'Marginal' Part‐Time Employment. Fact Sheet. Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2015. 2015/05/31/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mandl I, Curtarelli M, Riso S, Vargas O, Gerogiannis I. New Forms of Employment. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2015, 159 p. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rasmussen S, Nätti J, Larsen TP, Ilsøe A, Garde AH. Nonstandard employment in the nordics – toward precarious work? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies. 2019;9. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larsen TP, Mailand M. Lifting wages and conditions of atypical employees in Denmark‐the role of social partners and sectoral social dialogue. Industrial Relations Journal. 2018;49(2):88‐108. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mailand M, Larsen TP. Hybrid work – social protection of atypical employment in Denmark. Hans‐Böckler‐Stiftung; 2018. Report No. 2367‐0827.

- 6. Kalleberg A. Nonstandard employment relations: part‐time, temporary and contract work. Ann Rev Sociol. 2000;16:341‐365. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartoll X, Cortes I, Artazcoz L. Full‐ and part‐time work: gender and welfare‐type differences in European working conditions, job satisfaction, health status, and psychosocial issues. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(4):370‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nielsen ML, Dyreborg J, Lipscomb HJ. Precarious work among young Danish employees – a permanent or transitory condition? J Youth Stud. 2019;22(1):7‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ilsøe A, Felbo‐Kolding J. The role of physical space in labour–management cooperation: a microsociological study in Danish retail. Econ Ind Democracy. 2017;41(1):145‐166. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beckers DGJ, van der Linden D, Smulders PGW, Kompier MAJ, Taris TW, Van Yperen NW. Distinguishing between overtime work and long workhours among full‐time and part‐time workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33(1):37‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallie D, Gebel M, Giesecke J, Hallden K, Van der Meere P, Wielers R. Quality of work and job satisfaction: comparing female part‐time work in four European countries. Int Rev Sociol. 2016;26(3):457‐481. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandor E. Part‐time work in Europe. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bodin T, Çağlayan Ç, Garde AH, et al. Precarious employment in occupational health – an OMEGA‐NET working group position paper. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020, 46(3):321–329. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kreshpaj B, Orellana C, Burström B, et al. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020.46(3):235–247. 10.5271/sjweh.3875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health–a meta‐analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):443‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kivimaki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Keltikangas‐Jarvinen L. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(10):779‐783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coenen P, Gouttebarge V, van der Burght ASAM, et al. The effect of lifting during work on low back pain: a health impact assessment based on a meta‐analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(12):871‐877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim TJ, von dem Knesebeck O. Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health‐related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cottini E, Ghinetti P. Employment insecurity and employees' health in Denmark. Health Econ. 2018;27(2):426‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tijdens K. Are secondary part‐time jobs marginalized? Job characteristics of women employed less than 20 hours per week in the European Union. In: van der Lippe I, van Dijk L, eds. Women's Employment in a Comparative Perspective. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2001:203‐219. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodriguez E. Marginal employment and health in Britain and Germany: does unstable employment predict health? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(6):963‐979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Statistics Denmark . Documentation of statistics: Labour Market Account. https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/dokumentation/documentationofstatistics/labour‐market‐account

- 23. NRCWE . Tal og fakta om arbejdsmiljøet i Danmark ‐ metode [Numbers and facts about the working environment in Denmark ‐ method]. The National Research Centre for the Working Environment. https://arbejdsmiljodata.nfa.dk/metode.html

- 24. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):22‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Bronnum‐Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):12‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:103‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Healt. 2011;39:95‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Statistics Denmark . Statistikdokumentation for Arbejdsmarkedsregnskab 2015 [Statistic documentation of the Labor Market Accounting 2015]. Statistics Denmark, 2015.

- 29. Johnsen NF, Thomsen BL, Hansen JV, Christensen BS, Rugulies R, Schlünssen V. Job type and other socio‐demographic factors associated with participation in a national, cross‐sectional study of Danish employees. BMJ Open. 2019;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P. The internal and external validity of the Major Depression Inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med. 2003;33(2):351‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nielsen M, Nielsen L, Holte K, Andersson Å, Gudmundsson G, Heijstra T, et al. New forms of work among young people: Implications for the working environment, 2019.

- 32. Booth AL, van Ours JC. Job satisfaction and family happiness: the part‐time work puzzle. Econ J. 2008;118(526):F77‐F99. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain – implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Quart. 1979;24(2):285‐308. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fullerton AS, Dixon JC, McCollum DB. The institutionalization of part‐time work: cross‐national differences in the relationship between part‐time work and perceived insecurity. Soc Sci Res. 2020;87:102402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Green F, Tsitsianis N. An investigation of national trends in job satisfaction in Britain and Germany. Brit J Ind Relat. 2005;43(3):401‐429. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ilsøe A, Larsen TP, Bach ES, Rasmussen S, Madsen PK, Berglund T, et al. Non‐standard work in the Nordics. Troubled waters under the still surface. 2021. Report No.: 503.

- 37. Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, Vanroelen C, Tarafa G, Muntaner C. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:229‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burr H, Rauch A, Rose U, Tisch A, Tophoven S. Employment status, working conditions and depressive symptoms among German employees born in 1959 and 1965. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(6):731‐741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scott‐Marshall H, Tompa E. The health consequences of precarious employment experiences. Work. 2011;38(4):369‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Statistics Denmark . TIMES variabel ‐ TILSTAND_GRAD_AMR [TIMES variable ‐ TILSTAND_GRAD_AMR]. Statistics Denmark. https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/dokumentation/Times/moduldata‐for‐arbejdsmarked/tilstand‐grad‐amr

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

This study is based on anonymized micro data available from Statistics Denmark. Access to data can only be permitted through an affiliation with a Danish authorized environment. For further information on data and data access please see www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice.