Abstract

Red seaweed Chondracanthus canaliculatus, an underexploited algae species, was used as a potential source for the obtaining of carrageenan. Seaweed was treated under alkaline conditions using ultrasound alone or combined with conventional procedures, to improve the yield extraction. Color, syneresis behavior, water retention capacity, and functional groups of the gelling and non-gelling fractions of carrageenan were determined; these properties were compared with those of commercial carrageenans named A and B. Ultrasound alone or with heat significantly (p < 0.05) increased the yield extraction up to 41–45% and influenced color parameters, in comparison with conventional treatments. Functional groups kappa and iota, and alginates, were confirmed in both carrageenan fractions. Syneresis behavior was well fitted to a third-degree polynomial equation within days 1 to 6, after which, it reached a plateau. While, the use of ultrasound at room temperature gave carrageenan properties more similar to those of the commercial carrageenan type A.

Keywords: Red seaweed, Chondracantus canaliculatus, Carrageenan, Ultrasound extraction, Physicochemical properties

Introduction

Red seaweed is the main source of carrageenan, a class of sulphated galactose, located in the cell wall and intercellular matrix of different algae species such as Chondrus crispus, Gymnogongrus fucellatus, Soleria chordalis, Cystoclonium purpureum, and Kappaphycus alverezii, the latter being of main interest (Sahu et al., 2011; Webber et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2013; Manuhara et al., 2016). In the last decades, global production of seaweed increased from less than 4 million (90’s) to 32.4 million wet tons (2018) (FAO, 2020). The largest seaweed farming countries and carrageenan producers are China, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia and Tanzania that cover the demands of the main hydrocolloids obtained from seaweed: agar, alginate and carrageenan (Cai et al., 2013; FAO, 2020). While in the occidental countries, Mexico is considered a potential producer of various commercial seaweed species [(Phaeophyta, Macrocystis pyrifera, and three species of Rhodophyta (Gelidium robustum, Chondracanthus canaliculatus and Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis)] (Cai et al., 2013; Hernández-Herrera et al., 2018).

Carrageenan is highly demanded because of its unique functional properties that can be used to gel, thicken and stabilize food products and food systems (Imeson, 2009; Saha and Bhattacharya, 2010). Its structure consists of repeating disaccharide units of D-galactose and 3,6 anhydro-galactose linked by 3-β-D-galactose and 4-α-D-galactose, containing 20–40% sulphate ester groups (Imeson, 2009). Although, it has been proposed the idealized disaccharide structure with repeating units, seaweeds do not produce idealized and pure carrageenans, but rather more likely hybrid structures (Pereira et al., 2009). In addition, carrageenan can be classified as kappa (κ), iota (ι) and lambda (λ) types (Li et al., 2014; Zia et al., 2017), and based on its sulphate content, kappa carrageenan produces firm, rigid, brittle and thermos reversible gels of high strength on cooling; iota carrageenan produces weak, elastic and thermo reversible gels; while lambda carrageenan does not gel (Imeson, 2009; Webber et al., 2012; Zia et al., 2017). Nonetheless, carrageenan may be blended with other polysaccharides to develop new textures due to the specific interactions formed between materials, to improve or induce gelation (Chatziantoniou et al., 2019).

To improve carrageenan yield extraction, different methods have been tested using either water alone or under alkaline conditions [Na2CO3, Ca(OH)2, or KCl], followed by alcohol precipitation, drying, and subsequent carrageenan purification (Sahu et al., 2011; Hilliou et al., 2012). While, the application of heat or autoclave-assisted treatments to disrupt seaweed cell wall for a more efficient solvent penetration may also increase yields (Azis and Mahyati, 2019). Depending on the extraction conditions and seaweed species, carrageenan yields vary from 6.5% to 43%, where the highest are achieved under alkaline extraction (Maciel et al., 2008; Sahu et al., 2011; Hilliou et al., 2012; Souza et al., 2012; Manuhara et al., 2016). On the other hand, ultrasound is a technology used for different purposes (Gómez-Díaz and López-Malo, 2009; Pingret et al., 2013), and despite its efficiency to extract natural pigments and antioxidants (Zhu et al., 2015; Raza et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018a), little is known about its use to improve the extraction of carrageenan from seaweed.

This research assessed the extraction of carrageenan from red seaweed C. canaliculatus, an underexploited algae species produced in Baja California (Mexico), under conventional treatments assisted by ultrasound, to increase carrageenan yield. Carrageenan was characterized for its physicochemical properties, functional groups (gelling and non-gelling fractions), syneresis behavior and modelling using a third-degree polynomial equation. Additionally, carrageenan from C. canaliculatus was compared with two types of commercial carrageenan.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dried red seaweed (Chondracantus canaliculatus) acquired from Cultivos Marinos Integrados (San Quentin, Baja California, MEX) was donated by Danmark Inc. (Guadalajara, Jalisco, MEX). Samples of commercial carrageenan named as A and B type were also donated by Danmark Inc. Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), used as the extraction medium for carrageenan, was acquired from Golden BellMR Reagents, Materiales y Abastos Especializados S.A. de C.V. (Guadalajara, JAL, MEX).

Carrageenan extraction

Before carrageenan extraction, seaweed was cleaned from foreign matter and washed with plenty of tap water to remove excess of salt; then, it was dried in a laboratory oven at 55 °C for 12 h. The dehydrated material was sealed in polyethylene bags and stored at room temperature, until further use (Imeson, 2009).

From preliminary runs (data not shown), two treatments resulted in higher yields, T1: 2 h of agitation 25 °C, and T2: 1 h of agitation at 95 °C. This last treatment (T2) was applied to test the effect of heat on carrageenan yield, but reducing the exposure time to avoid material´s degradation. Thus, additional two treatments, T3 and T4, were run under similar conditions to T1 and T2, respectively, assisted by ultrasound. The control was the carrageenan extracted under soaking in distilled water, at 25 °C for 2 h.

Twenty grams of red seaweed were hydrated in a 0.1 M Na2CO3 solution in proportions of 1:20 seaweed: solution. Before extraction conditions, samples were left to stand for 15 min until their complete hydration, and then, seaweeds were ground to a coarse particles size using a laboratory blender, to promote a more efficient diffusion of the extraction medium into the fibrous material; later, agitation at 500 rpm was used for all treatments. For T3 and T4, after the traditional treatment, ultrasound was applied at 25 °C for 30 min, using a Branson 2510 equipment (Fairfield, USA). Subsequently, samples were filtered under vacuum for pigments removal by adding 25 g of Celite, then seaweed with Celite residues were discarded; the remaining Celite residues in the filtered gel solution were separated naturally by sedimentation. The gel solutions were dehydrated in a spray dryer (Labplant SD-basic, Essex, UK), with inlet temperature of 50 °C, chamber temperature of 160 °C, and flow rate of 0.45 L/h. Carrageenan powder was stored in polyethylene bags, until their further use. Extraction yield was calculate as follows (Reis et al., 2011):

where Wc is the weight (g) of dried carrageenan and Ws is the initial weight (g) of dried seaweed used before extraction.

Color

The color of carrageenan was determined using a colorimeter (CR410, Konica Minolta, Stone Ridge, USA). The CIELAB color space was selected to measure the color coordinates L* (luminosity), a* (- green, + red), b* (-blue, + yellow); and for each sample, five readings were taken randomly at different points. Also, color saturation or Chroma (C*) and hue angle (h*) were measured; these parameter represents the purity of the color and the variations on color when combined with others, respectively (Restrepo and Aristizábal, 2010). Both parameters C* and h* were calculated using the following equations:

Functional groups

The functional groups of the gelling and non-gelling fractions of carrageenan were determined with the transmission method (laminated sample) by the Fourier Transform Infrared spectrophotometry (FT-IR), using a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), in the region between 4000 to 700 cm−1 (Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011).

Non-gelling fraction

Two grams of carrageenan were added with 200 mL of 2.5% potassium chloride solution, under agitation for 1 h; samples were left to stand overnight and stirred again. After, the dispersion was centrifuged at 1000 × g, for 15 min, and then, another 200 mL of potassium chloride solution were added to the supernatant and were again centrifuged. The supernatant was coagulated with 2 volumes of 85% ethanol, and the coagulum formed was washed with more ethanol; the excess liquid was removed and dried at 60 °C for 2 h (FAO JECFA, 2007); this analysis was performed in duplicate. The non-gelling part of the carrageenan comprises the fraction of lambda carrageenan.

Gelling fraction

The sediment obtained from the centrifuged samples was diluted in 250 mL cold water, heated at 90 °C for 10 min, and cooled to 60 °C. The dispersion was coagulated with ethanol, washed and dried, similarly to the non-gelling fraction, as described above (FAO JECFA, 2007). The gelling part of the carrageenan comprises the fractions of iota and kappa carrageenan.

Gel syneresis

For syneresis assays, gels were prepared with 4% carrageenan in distilled water (w/w). Samples were brought to 80 °C under constant stirring at 700 rpm, until complete solubilization; subsequently, samples were placed on petri dishes, and were left to cool down to room temperature. Later, they were kept refrigerated at a controlled temperature of 7 °C. The loss of weight was monitored for 14 days, and measurements were taken after carefully removing the water from the plate wall with the aid of a paper napkin. The syneresis ratio (Rs) was calculated as (Ako, 2015):

where We is the weight (g) of solvent released by the gel and Wg is the weight (g) of the initial gel (Ako, 2015).

The behavior of syneresis as a function of time was fitted using a third-degree polynomial equation as follows:

where , , , and are the polynomial fitting parameters and is the time (days).

The Sum of Squares Due to Error (SSE), it is also called the summed square of residuals and is the deviation of the response values from the fit to the response values. It can be calculated as:

where yi is the observed data value and fi is the predicted value from the fit, wi is the weighting applied to each data point from to , usually wi = 1. A value closer to zero indicates that the model has a smaller random error component, and that fitting will be more useful for prediction.

Water retention capacity

To test the capability to retain water, carrageenan gels were prepared at a concentration of 0.5% carrageenan in a 2% brine solution of salt (NaCl) (method provided by Danmark Inc.). The solutions were constantly stirred with heat, until reaching a temperature of 72 °C; then, samples were cool down to 25 °C, before placing them in a refrigerator for 1 h at 4 °C. The gels were then emptied into a glass funnel with filter paper placed on a graduate cylinder. Afterwards, the amount of water release for 1 h was measured and the water retention was calculated as follows:

Statistical analysis

The effect of the treatments on the physicochemical and functional properties of carrageenan obtained from red seaweed was determined with the analysis of variance ANOVA and the comparison of means was performed with the LSD test at a confidence level of 95% (α = 0.05). All statistical analyzes were performed using the STATGRAPHICS Centurion XV software version 15.2.06.

Results and discussion

Carrageenan yield and color

Table 1 summarizes carrageenan yields obtained from red seaweed C. canaliculatus under conventional treatments alone or assisted with ultrasound, compared with those reported for other algae species. With all treatments tested, higher yields were achieved under alkaline extraction with Na2CO3 than those obtained only using distilled water (14.30% control), and statistically, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatments group. Although alkaline extraction at room temperature (26 ºC) enhanced carrageenan yield to 33.90%, the use of heat promoted a further increased up to 37.82%; besides, it was noticeable an important reduction on the extraction time by a half. This effect is attributed to heat that promotes the disruption of the cell wall with the consequent release of greater amount of material (Martínez-Sanz et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Comparison of carrageenan yield obtained from C. canaliculatus with other seaweed species

| Seaweed | Treatment | Yield (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. canaliculatus | Control: 2 h soaking/ distilled water/ 25 °C | 14.30 ± 1.53a | This study |

| T1: 2 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution/ 25 °C | 33.90 ± 3.25b | This study | |

| T2: 1 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution/ 95 °C | 37.82 ± 2.01bc | This study | |

| T3: 2 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution/ 25 °C/ 30 min ultrasound | 45.05 ± 1.44de | This study | |

| T4: 1 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution/ 95 °C/ 30 min ultrasound | 41.00 ± 1.10d | This study | |

| K. alvarezii | Ca(OH)2/KCl/heat | 19.50 – 43.91 | Manuhara et al., (2016) |

| M. stellatus | Na2CO3/heat | 14.00 – 36.00 | Hilliou et al., (2012) |

| G. birdiae | Water/heat | 27.20 | Souza et al., (2012) |

| K. alvarezii | Ca(OH)2 /heat | 30.00 – 39.00* | Sahu et al., (2011) |

| G. birdiae | Water/room temperature | 6.50 | Maciel et al., (2008) |

*only of k-carrageenan

Subscripts with different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) between treatments, using the LDS statistical test (Least significant difference) at a confidence level of 95%

Regarding carrageenan yields reported elsewhere (Table 1), the percentages vary within a wide range of 6.5–43.91%, depending on the type of extraction agent [water, Ca(OH)2, NaOH, KOH, Na2CO3] and algae species, for instance, Mastocarpus stellatus, Kappaphycus alvarezii, and Gracilaria birdiae. As noted, the extraction with water at room temperature causes the less release of carrageenan, while high yields are reported under alkaline conditions, assisted by heat treatment (Maciel et al., 2008; Sahu et al., 2011; Hilliou et al., 2012; Souza et al., 2012; Larotonda et al., 2016). Further, the combination of extraction agents at different concentrations may be another alternative to improve carrageenan yields (Manuhara et al., 2016).

On the other hand, in this study, it is noteworthy that the use ultrasound benefited the extraction with superior yields up to 41–45%, thus, enhancing extraction efficiency. This was attributed to the effect of ultrasound cavitation waves, which disrupt the cell wall or cell membranes, therefore, it occurs an increase of solvent penetration into the material by cellular diffusion (Gómez-Díaz and López-Malo, 2009). It is also known that the shock produced by ultrasonic waves causes pores enlargement and cell disruption with the concomitant release of the material, therefore, increasing yield extraction (Wang et al., 2018b). As well, it was observed that between both ultrasound-assisted treatments, the use of heat reduced yield percentages, probably because of material´s degradation due to the breaking of some bonds at a molecular level (Martínez-Sanz et al., 2019). This suggest that temperatures lower than those used could yet maintain high yields without damaging carrageenan. Nonetheless, with ultrasound at room temperature, higher yields were obtained in comparison with those reported for other algae species (Table 1).

Most types of commercial carrageenan retain a light cream color after extraction and purification, since some pigments remain in the product; and accordingly, all experimental and commercial carragenans presented such color. Commercial carrageenan types A and B showed differences in their color parameters, observing that type B tended to be more similar to the conventional treatments (1 and 2) for L*, b*, and C*, while type A was more alike to ultrasound assisted treatments (3 and 4), for the same parameters (Table 2); and again, factors mention above, like extraction conditions and seaweed species mainly influence color. With respect to carrageenan from C. canaliculatus, the luminosity (L*) showed differences between the conventional and the ultrasound assisted treatments (Table 2). Treatments 1 and 2 were closer to the white region (white: L* = 100 and black: L* = 0), with L* values within a narrow range of 91.18–91.34, than those of treatments 3 and 4, which gave lower values of 83.36–84.47, much further from the white region. The increase in the intensity of the cream color may indicate that ultrasound penetrates deeper into the cell wall, and along with gelling materials, it also extracts more pigments; this effect has been observed in the extraction of natural plant pigments under ultrasound such as betaxantin or betacyanin (Wang et al., 2018a). For the color coordinate a*, all treatments gave negative values, indicating that they tend to green on the color space, but both commercial samples showed positive values within the red region. Conversely, the coordinate b* showed positive values within the yellow region, for all commercial and treatment groups. Statistically, there were significant differences (p < 0.05) between conventional and ultrasound treatments for all color parameters. Furthermore, a* and b* are only shades of color not related to the visual perception but to a standard, whereas chromaticity or C*, indicates the intensity of color, and is an attribute of visual perception; thus, color of certain stimuli is evaluated in terms of “weak-strong” or “pale-intense” visual sensation. Thus, C* values of conventional treatments were within a range of 12.10–14.40 close to that of the carrageenan type B, and these treatments showed lower intensity of color than those of ultrasound, which were in a range of 15.83–16.03, more comparable to the type A. On the other hand, hue (h*) is an attribute of visual sensation, which resembles to one of the perceived colors (red, yellow, green, and blue) or a combination of them. All treatments exhibited greater h* values from those of the commercial samples, indicating that carrageenan from C. canaliculatus is closer to the reddish tones and visually darker than commercial carrageenan, being closer to the yellow color. Such differences in h* may be attributed to the algae specie or to the purification process of the material used in the commercial samples (unknown methods of purification). In addition, the use of ultrasound slightly increased C* and h* values with respect to the conventional treatments (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Color parameters of commercial and C. canaliculatus seaweed carrageenan

| Treatment | L* | a* | b* | C* | h* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 91.18 ± 0.48d | − 1.24 ± 0.09c | 11.84 ± 0.30a | 14.40 ± 0.35b | 95.97 ± 0.26a |

| 2 | 91.34 ± 0.35de | − 1.32 ± 0.14b | 12.00 ± 0.22ab | 12.10 ± 0.23a | 96.25 ± 0.50ab |

| 3 | 84.47 ± 0.51ab | − 2.03 ± 0.13a | 15.70 ± 0.15c | 15.83 ± 0.86c | 97.39 ± 0.09c |

| 4 | 83.36 ± 0.67a | − 2.10 ± 0.43ab | 17.10 ± 0.84d | 16.03 ± 0.78 cd | 97.57 ± 1.90 cd |

| Commercial carrageenan | |||||

| A | 85.51 | 1.02 | 17.09 | 17.13 | 86.60 |

| B | 90.24 | 0.42 | 13.41 | 13.42 | 88.21 |

T1: 2 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution/ 25 °C, T2: 1 h agitation/ Na2CO3 solution / 95 °C; T3 and T4 were run under similar conditions to T1 and T2, respectively, with additional 30 min of ultrasound

Subscripts with different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) between treatments, using the LDS (Least significant difference) statistical test at a confidence level of 95%

Functional groups by FT-IR

Carrageenan properties are related to their particular functional groups. However, most published investigations report carrageenan functional groups of the whole sample. A contribution of this work was to separate the gelling and non-gelling fractions and perform the FT-IR analysis on each of them. This allowed to identify more specifically the functional groups that contribute with the characteristics of carrageenan obtained from C. canaliculatus.

Gelling fraction

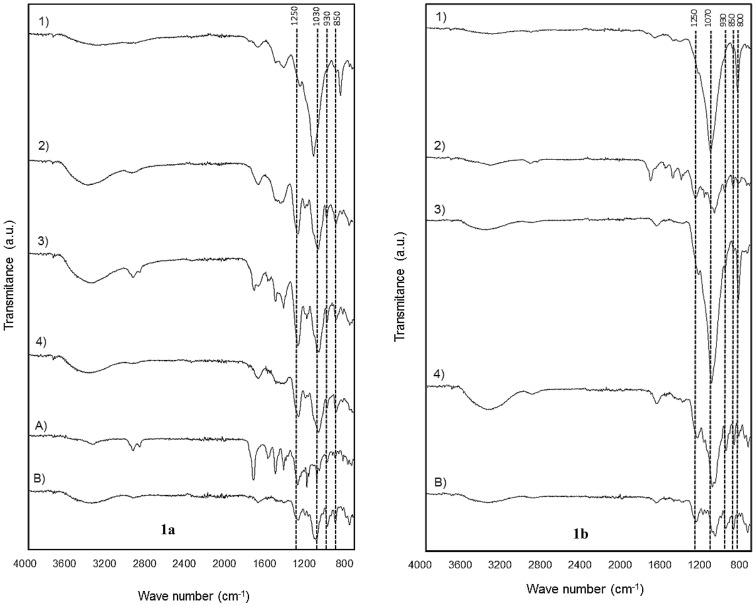

All treatments and commercial samples displayed a similar infrared spectra pattern of carrageenan gelling fraction from C. canaliculatus (Fig. 1a). Vibrations detected in the region of 3200–3400 cm−1, which corresponds to –OH groups, were observed in all treatments and commercial samples; because of the length of the band, it was related to intermolecular associations of polymeric type. The band identified between 1210 and 1260 cm−1 confirmed the presence of sulphate ester (O-SO3) groups (S) that predominate in carrageenans. Particularly, treatments 2, 3 and 4 displayed peaks of strong intensity, while intermediate and low intensities were observed in both commercial samples and treatment 1, respectively. Besides, as treatment 3 (ultrasound/room temperature) exhibits the peak of more intensity than the rest of the treatments, this suggests that ultrasound enhances the breakdown of the seaweed cell walls, and therefore, promotes a high release of hybrid structures. For other algae species, the presence of such groups in this region is related to hybrid structure containing kappa-iota carrageenan, as confirmed in previous studies for the Solieriaceae and Gigartinacean kappa-2 family (van de Velde, 2008; Pereira et al., 2009; Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011; Vázquez-Delfín et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2018; Chitra et al., 2019).

Fig. 1.

Infrared spectra of the gelling fraction (1a) and non-gelling fraction (1b) of carrageenan from C. canaliculatus and commercial carrageenans A and B

On the other hand, bands detected between 1100–1150 and 1010–1030 cm−1 are associated to C–O and C–C stretching vibrations of pyranose rings that appear in polysaccharides (Table 3), such as carrageenan or alginate (Pereira et al., 2013); thus, C. canaliculatus could be a potential source of alginate that is mostly rich in β-D- mannuronic acid and α-L- guluronic acid (Pereira et al. 2013). The band between 928–933 cm−1 displayed the presence of 3,6-anhydro-D-galactose (DA), a characteristic functional group found in kappa- and iota- carrageenan (Pereira et al., 2009; Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011; Vázquez-Delfín et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2018; Chitra et al., 2019) that is responsible for the rigidity of gels (Imeson, 2009; Zia et al., 2017); this band was present in the commercial samples, and also in treatments 2, 3 and 4. The 840–850 cm−1 band is assigned to D-galactose-4-sulphate (G4S), groups that contribute to the gelling properties, and are also characteristic of kappa- and iota-carrageenan (Pereira et al., 2009; Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011). This group appeared in all treatments and commercial samples, but the peak intensity was sharper in treatments 2, 3 and 4, indicating that under such conditions, carrageenan from C. canaliculatus contains groups that impart gelling properties. Moreover, only in treatment 1, it was detected a vibration at 800–805 cm−1 linked to 3,6 anhydro-D-galactose-2-sulphate groups (DA2S) common to iota- carrageenan (Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011), which contributes with the elastic and thixotropic properties of gels (Zia et al., 2017).

Table 3.

Functional groups of phycocolloids of C. canniculatus identified by FTIR

| Wavenumbers (cm −1) | Functional group | Letter code | Type of phycocolloid* | Treatments** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kappa (κ) | Iota (ι) | Lambda (λ) | Gelling fraction | Non-gelling fraction | |||

| 1210–1260 | Sulphate ester (O-SO3−) | S | + | + + | + + + | 1+(2,3,4)++ | (1,3)+(2,4)++ |

| 1100–1150 | C–O and C–C stretching vibrations of pyranose ring: β-D- mannuronic acid | – | Alginates | 2,3,4 | 2,4 | ||

| 1070 | C–O band of 3,6-anhydrogalactose | DA | + | + | _ | 1 | 1,3 |

| 1010—1030 | C–O and C–C stretching vibrations of pyranose ring:α-L- guluronic acid | – | Alginates | 2,3,4 | 2,4 | ||

| 928 – 933 | 3,6-anhydro-D-galactose | DA | + | + | _ | 2,3,4 | 2,4 |

| 840—850 | D-galactose-4-sulphate | G4S | + | + | _ | 2,3,4 | 2,4 |

| 825–830 | D-galactose-2-sulphate | G2S | _ | _ | + | ND | ND |

| 815–820 | D-galactose-2,6-disulphate | D2S,6S | _ | _ | + | ND | ND |

| 800—805 | 3,6-anhydro-D-galactose-2-sulphate | DA2S | _ | + + | _ | 1 | (1,3)++(2,4)+ |

Peak intensity: -Absent; + medium; ++ strong; +++ very strong. ND: Not detected

*Pereira et al. (2009), Pereira et al. (2013),Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez (2011)

**The numbers from 1 to 4 correspond to the applied treatments in which signal bands were identified. The grouping of various numbers differentiates between the peak intensities, and the cross symbol used as superscript indicates that the same peak intensity was obtained for these treatments

Non-gelling fraction

Infrared spectra of the non-gelling fraction of carrageenan from C. canaliculatus for all treatments and commercial carrageenan are showed in Fig. 1b. At 1250 cm−1, peaks of low intensity appeared in treatments 1 and 3, indicating the presence of sulphate ester (O-SO3) groups (S) that correspond to kappa- or iota- carrageenan (Pereira et al., 2009), whereas treatments 2, 4, and commercial B type carrageenan showed peaks of stronger intensity in this region; again, this evidences the efficiency of ultrasound to extract bioactive compounds. At 1070 cm−1 there was a characteristic C–O stretching band of 3,6-anhydrogalactose (DA), which was very strong in treatments 1 and 3, and which is related to kappa-carrageenan; this band has also been observed in samples containing alginates or carrageenan, as reported elsewhere (Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011; Pereira et al., 2013). Henceforth, it seems that the non-gelling fraction of carrageenan from C. canaliculatus was particularly rich in such groups, because of the intensity of the peaks. In treatments 2 and 4, peaks at this vibration were slightly displaced, probably by the effect of heat applied in both treatments, either under agitation alone or with ultrasound. For the same treatments (2 and 4), there was observed the presence of bands ranging from 1100–1150 to 1010–1030 cm−1 that are associated to β-D- mannuronic acid and α-L- guluronic acid, respectively; again, confirming the presence of alginates (Pereira et al., 2013). Also, these treatments (2 and 4) and commercial type B carrageenan, exhibited another bands identified in the regions of 928–933 and 840–850 cm−1 that account for 3,6-anhydro-D-galactose (DA) and D-galactose-4-sulphate (G4S), characteristic functional groups of kappa- and iota- carrageenan (Pereira et al., 2009; Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011); treatment 4 displayed the peak of major intensity indicating that heat promotes a mayor release of these groups when this is combined with ultrasound. Another band exhibited at 800–805 cm−1, which corresponds to 3,6 anhydro-D-galactose-2-sulphate (DA2S), is characteristic of iota-type carrageenan; therefore, the non-gelling fraction of C. canaliculatus is also rich in this compound. This can be corroborated by the strong peaks observed in treatments 1 and 3 and the low intensity peaks of treatments 2 and 4, except the commercial type B, where a peak did not appear, probably because this type of carrageenan does not contain DA2S groups. It is important to mention that the commercial carrageenan type A had no remnants of the non-gelling fractions, meaning that this sample is highly purified and mainly rich in kappa-carrageenan.

Thus, these findings indicate that the gelling and non-gelling fractions of carrageenan from C. canaliculatus are rich in functional groups S, DA, G4S, and DA2S (Table 3), with the predominance of a hybrid mixture of kappa- and iota- carrageenan and alginate, over lambda- type that was not identified in any of the fractions. The use of ultrasound and heat favors the extraction of hybrid gelling structures; nonetheless, the gelling properties of carrageenan can be improved with further treatment using potassium and calcium ions, respectively (Thrimawithana et al., 2010).

In comparison with other sources of algae, the FTIR analysis of both fractions of carrageenan showed clear similarities with spectra of red seaweeds M. stellatus, G. pistillata, C. acicularis, N. helminthoides or D. contorta. Particularly, the chemical composition of M. stellatus and G. pistillata shows the presence of galactans with galactose as major component and also sulphate groups (Gómez-Ordóñez and Rupérez, 2011), such as those detected here.

Gel syneresis and water holding capacity

Syneresis behavior (Rs) of C. canaliculatus and commercial carrageenan gels was examined during 14 days (Fig. 2). All experimental and commercial carrageenan gels showed a similar behavior on Rs that increased from day 1 to 6. As it is observed, within the first two days, experimental carrageenan had a faster rate of syneresis, releasing approximately 50%, and by day 6, reaching the maximum percentage of 95%, independently on the extraction treatment. From day 6 and until the end of storage, syneresis formed a plateau, with a constant linear tendency. In addition, treatments 1 and 4 displayed close patterns one respect to another, as well as, treatment 1 and type A; in contrast, type B displayed a more pronounced curvature different from the other samples. Yet, the presence of alginate detected by FT-IR, may sustain the fact that all C. canaliculatus carrageenan samples exhibited high syneresis, since alginate structures do not tightly hold water as pointed out elsewhere (Imeson, 2009).

Fig. 2.

Syneresis behavior of carrageenan from C. canaliculatus of treatments 1–4, and commercial carrageenans A and B, during 14 days at 7 °C

The non-linear pattern of syneresis was well fitted with a third-degree polynomial in the range from day 1 to 6 (Fig. 2). R-squares of 1 for all curves and very small SSE values indicated the goodness of fit of the equation (Table 4), while the stationary behavior displayed in the range from days 6 to 14, was well fitted to a linear trend. This behavior is related to the gel syneresis process, which has two stages: a first stage of rapid syneresis and a second stage of slow syneresis rate. Also, from Table 4, the parameters of the model a1-a4 were quite close for treatment 3 and commercial type A, and for treatments 1 and 4, thus, corroborating among them, the resemblance with their Rs values and curve trend behavior. Unlike other studies reported (Ako, 2015), where the syneresis behavior of carrageenan gels follows simple linear trends, this type of fitting is of crucial importance, and based on the benefits of empirical models, it makes possible to predict stabilization time for particular carrageenans, or well to correlate stability or change in properties of those systems containing carrageenan.

Table 4.

Fitting parameters of syneresis radius (Rs) as function of time for C. canniculatus and commercial carrageenans

| Model Parameter | Treatment | Commercial type A | Commercial type B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 0.9515 | 0.539 | 0.144 | 0.9485 | 0.04346 | 1.449 | |

| − 10.18 | − 7.437 | − 2.8 | − 9.999 | − 2.211 | − 16.16 | |

| 42.42 | 40.86 | 27.25 | 41.81 | 27.51 | 60.44 | |

| − 2.17E-14 | 2.00E-15 | 1.88E-14 | − 2.14E-14 | 2.50E-14 | − 4.23E-14 | |

| SSE | 4.11E-27 | 4.58E-28 | 1.21E-27 | 5.56E-27 | 1.69E-27 | 2.72E-26 |

a1, a2, a3 and a4 represent the constants of the third-degree polynomial equation. SEE is the sum of squares due to error and represents the deviation of the response values from the fit of the equation

On the other hand, water retention capacity (WRC) of those treatments applying ultrasound was significantly (p < 0.05) lower between 18.0 and 22%, in comparison with those of conventional treatments 1 and 2 that exhibited higher percentages of 27.0 ± 1.2%. This suggests that ultrasound, although it is known to protect sensitive natural compounds (Zhu et al., 2015; Raza et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018a), could affect to some extent carrageenan functional groups, producing soft gels with low WRC. Similarly, carrageenan from conventional treatments also produced gels of low WRC that confirms the hybrid structures and alginates detected in this algae species; in comparison, commercial A and B carrageenans produced firm gels to touch, during gel´s process elaboration.

Although, traditional methods are useful for the extraction of carrageenan, in this study, the additional application of ultrasound demonstrated to enhance yield extraction of carrageenan; thus, the high yields are attributed to both, extraction conditions and type of algae. In this context, the Gigartinaceae family, to which C. canaliculatus belongs, is known to produce k/i-hybrids of carrageenan, in contrast with the Solieriaceae family, whose species produce more k-carragenan, like K. alvarezii, one of the most commercially exploited red seaweed (van de Velde, 2008). Nonetheless, further modification of the hybrid kappa- and iota- groups, with potassium or calcium ions (Thrimawithana et al., 2010), could improve carrageenan gelling properties of C. canaliculatus that exhibits potential for the obtaining of phycocolloids used as food additives.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank to the Universidad de Guadalajara for their support to develop this research, as well as, Danmark Inc. for the donation of the seaweed and invaluable advises.

Declaration

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ako K. Influence of elasticity on the syneresis properties of κ-carrageenan gels. Carbohydrate Polymers 115:408–414 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azis A, Mahyati. Optimization of temperature and time in carrageenan extraction of seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) using ultrasonic wave extraction methods. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 370:12076 (2019)

- Cai J, Hishamunda N, Ridler N. Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming: a global synthesis. Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 580:5–59 (2013)

- Chatziantoniou SE, Thomareis AS, Kontominas MG. Effect of different stabilizers on rheological properties, fat globule size and sensory attributes of novel spreadable processed whey cheese. European Food Research and Technology 245:2401–2412 (2019)

- Chitra R, Sathya P, Selvasekarapandian S, Monisha S, Moniha V and Meyvel S. Synthesis and characterization of iota-carrageenan solid biopolymer electrolytes for electrochemical applications. Ionics 25:2147–2157 (2019)

- Compendium of Food Additive Specifications, Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (FAO JECFA), 68 th meeting, Monographs 4 (2007)

- Food and Agriculture Organization. FAO 2020. El estado mundial de la pesca y la acuicultura 2020. La sostenibilidad en acción. Roma. Available from: 10.4060/ca9229es. Accessed Dec. 22, 2020. In Spanish

- Gómez-Díaz J, López-Malo A. Aplicaciones del ultrasonido en el tratamiento de alimentos. Temas Selectos de Ingeniería en Alimentos 3:59–73 (2009). In spanish

- Gómez-Ordóñez E, Rupérez P. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy as a tool for polysaccharide identification in edible brown and red seaweeds. Food Hydrocolloids 25:1514–1520 (2011)

- Hernández-Herrera RM, Santacruz-Ruvalcaba F, Briceño-Domínguez DR, Di Filippo-

- Herrera DA, Hernández-Carmona G. Seaweed as potential plant growth stimulants for agriculture in Mexico. Hidrobiológica 28(1):129-140 (2018)

- Hilliou L, Larotonda FDS, Abreu P, Abreu MH, Sereno AM, Goncalves MP. The impact of seaweed life phase and postharvest storage duration on the chemical and rheological properties of hybrid carrageenans isolated from Portuguese Mastocarpus stellatus. Carbohydrate Polymers 87:2655–2663 (2012)

- Imeson A. Food stabilisers, thickeners and gelling agents. John Wiley & Sons (2009)

- Larotonda FDS, Torres MD, Gonçalves MP, Sereno AM, Hilliou L. Hybrid carrageenan-based formulations for edible film preparation: Benchmarking with kappa carrageenan. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 133: 42263 (2016)

- Li L, Ni R, Shao Y, Mao S. Carrageenan and its applications in drug delivery. Carbohydrate Polymers 103:1–11 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maciel JS, Chaves LS, Souza BWS, Teixeira DIA, Freitas ALP, Feitosa JPA, de Paula RCM. Structural characterization of cold extracted fraction of soluble sulfated polysaccharide from red seaweed Gracilaria birdiae. Carbohydrate Polymers 71:559–565 (2008)

- Manuhara GJ, Praseptiangga D, Riyanto RA. Extraction and characterization of refined K-carrageenan of red algae [Kappaphycus Alvarezii (Doty ex PC Silva, 1996)] originated from Karimun Jawa Islands. Aquatic Procedia 7:106–111(2016)

- Martínez-Sanz M, Gómez-Mascaraque LG, Ballester AR. Martínez-Abad A, Brodkorb A, López-Rubio A. Production of unpurified agar-based extracts from red seaweed Gelidium sesquipedale by means of simplified extraction protocols. Algal Research 38:101420 (2019)

- Pereira L, Amado AM, Critchley AT, Van de Velde F, Ribeiro-Claro PJA. Identification of selected seaweed polysaccharides (phycocolloids) by vibrational spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR and FT-Raman). Food Hydrocolloids 23:1903–1909 (2009)

- Pereira L, Gheda SF, Ribeiro-Claro PJA. Analysis by vibrational spectroscopy of seaweed polysaccharides with potential use in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. International Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry (2013)

- Pingret D, Fabiano-Tixier A-S, Chemat F. Degradation during application of ultrasound in food processing: A review. Food Control 31:593–606 (2013)

- Raza A, Li F, Xu X, Tang J. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of antioxidant polysaccharides from the stem of Trapa quadrispinosa using response surface methodology. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 94:335–344 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reis RP, Loureiro RR, Mesquita FS. Does salinity affect growth and carrageenan yield of Kappaphycus alvarezii (Gigartinales/Rhodophyta)? Aquaculture Research 42:1231–1234 (2011)

- Restrepo JI, Aristizábal ID. Conservación de fresa (fragaria x ananassa duch cv. camarosa) mediante la aplicación de recubrimientos comestibles de gel mucilaginoso de penca sábila (aloe barbadensis miller) y cera de carnaúba. Vitae 17:252–263 (2010) In Spanish

- Saha D, Bhattacharya S. Hydrocolloids as thickening and gelling agents in food: a critical review. Journal of Food Science and Technology 47:587–597 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sahu N, Meena R, Ganesan M. Effect of grafting on the properties of kappa-carrageenan of the red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex Silva. Carbohydrate Polymers 84:584–592 (2011)

- Souza BWS, Cerqueira MA, Bourbon AI, Pinheiro AC, and Martins JT, Teixeira JA, Coimbra MA, Vicente AA. Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide from the red seaweed Gracilaria birdiae. Food Hydrocolloids 27:287–292 (2012)

- Thrimawithana TR, Young S, Dunstan DE, Alany RG. Texture and rheological characterization of kappa and iota carrageenan in the presence of counter ions. Carbohydrate Polymers 82:69–77 (2010)

- Torres MD, Chenlo F, Moreira R. Structural features and water sorption isotherms of carrageenans: A prediction model for hybrid carrageenans. Carbohydrate Polymers 180:72–80 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- van de Velde F. Structure and function of hybrid carrageenans. Food Hydrocollois 22:727–734 (2008)

- Vázquez-Delfín E, Robledo D, Freile-Pelegrín Y. Microwave-assisted extraction of the Carrageenan from Hypnea musciformis (Cystocloniaceae, Rhodophyta). Journal of Applied Phycology 26:901–907 (2014)

- Wang H, Shi L, Yang X, Hong Rui, Li L. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of natural yellow pigment from Physalis pubescens L. and its antioxidant activities. Journal of Chemistry 2018 (2018a)

- Wang L, Xu B, Wei B, Zeng R. Low frequency ultrasound pretreatment of carrot slices: Effect on the moisture migration and quality attributes by intermediate-wave infrared radiation drying. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 40:619–628 (2018b) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Webber V, de Carvalho SM, Barreto PLM. Molecular and rheological characterization of carrageenan solutions extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii. Carbohydrate Polymers 90:1744–1749 (2012) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhu C, Zhai X, Li L, Wu X, Li B. Response surface optimization of ultrasound-assisted polysaccharides extraction from pomegranate peel. Food Chemistry 177:139–146 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zia KM, Tabasum S, Nasif M, Sultan, Aslam N, Noreen A, Zuber M. A review on synthesis, properties and applications of natural polymer based carrageenan blends and composites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 96:282–301 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed]