Dear Editor:

We read with great interest the article by Fan et al1 published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology on clinical features of COVID-19-related liver functional abnormality. This study focused on hepatic manifestations of COVID-19. Few other small studies of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) describe the disease course of COVID-19 in the setting of fatty liver disease, although the clinical course of these patients still remains unclear.2 Thus, we hypothesized that the presence of NAFLD can influence the epidemiologic aspects related to COVID-19, including infectivity and disease-related outcomes.

We conducted a population-based nationwide cohort study using data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service, which is linked to general health examination records.3 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sejong University (SJU-HR-E-2020-003). A total of 74,244 Korean individuals ≥20 years of age who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing between January 1 and May 30, 2020 were included.

Patients were classified into 3 groups. Preexisting NAFLD was defined when patients met 1 of the following criteria: (1) hepatic steatosis index (HSI) ≥36; (2) fatty liver index (FLI) ≥60; or (3) claim-based definition indicated by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (K75.8 and K76.0), with at least 1 claim within the observation period.4 We generated 3 cohorts using these definitions: (1) HSI-NAFLD cohort, (2) FLI-NAFLD cohort, and (3) claim-based NAFLD cohort. The main outcomes were the positive laboratory SARS-CoV-2 tests, severe clinical COVID-19 illnesses (requirement of oxygen therapy, administration of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, COVID-19-related death),5 , 6 and COVID-19-related deaths. The observational period was from January 1 to July 30, 2020.

We used Firth logistic regressions (an approach that can be used with small sample size) to adjust for potential confounders: age; sex; region of residence; past medical history/comorbidities (tuberculosis, stroke, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and dyslipidemia); systolic and diastolic blood pressure; fasting blood glucose; glomerular filtration rate; household income; smoking; alcoholic drinks; sufficient aerobic activity; and current medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.7 A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Among 74,244 adults (age groups: 34.4% [20–39 years], 36.6% [40–59 years], and 29.0% [≥60 years]), 36,060 were male (48.5%); and 26,041 (35.1%), 19,945 (73.1%), and 8927 (12.0%) subjects had HSI-NAFLD, FLI-NAFLD, and claims-based NAFLD, respectively. During the observation period, 2251 (3.0%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 438 (0.6%) had severe COVID-19 illness, and 45 (0.06%) suffered COVID-19-related deaths.

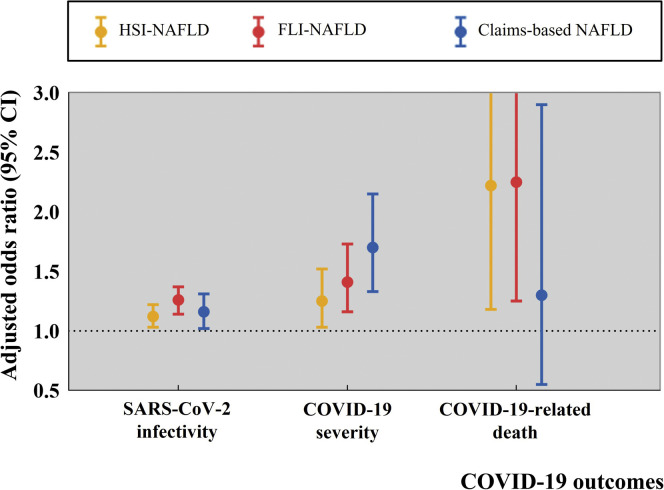

Subjects with HSI-NAFLD had a high risk of COVID-19 infection (1413/48,203 [2.9%] for subjects without HSI-NAFLD vs 838/26,041 [3.2%] for those with HSI-NAFLD; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.22), severe COVID-19 disease (259/48,203 [0.5%] vs 179/26,041 [0.7%]; aOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03–1.52), and significant COVID-19-related deaths (21/48,203 [0.04%] vs 24/26,041 [0.09%]; aOR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.18–4.00). We found similar trends when we used FLI to define NAFLD. Subjects with FLI-NAFLD had higher risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection (561/17,421 [3.2%] for subjects without FLI-NAFLD vs 629/17,421 [3.5%] for those with FLI-NAFLD; aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.14–1.37), severe COVID-19 infection (290/54,299 [0.5%] for subjects without FLI-NAFLD vs 148/19,945 [0.7%] for those with FLI-NAFLD; aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16–1.73), and COVID-19-related death (25/54,299 [0.05%] for subjects without FLI-NAFLD vs 20/19,945 [0.10%] for those with FLI-NAFLD; aOR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.25–3.98). Subjects classified as NAFLD based on claims seemed to have higher risk for COVID-19 (1925/65,317 [3.0%] for subjects without claim-based NAFLD vs 323/8830 [3.7%] for those with claim-based NAFLD; aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02–1.31) and severe COVID-19 progression (349/65,317 [0.5%] for subjects without claim-based NAFLD vs 89/8927 [1.0%] for those with claim-based NAFLD; aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.33–2.15) than non-NAFLD subjects (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Summary of the main study findings.

Through a large-scale, population-based, nationwide cohort study, we investigated the potential association between the presence of NAFLD and risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positive and COVID-19 severity and mortality. We identified that the NAFLD was associated with a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and COVID-19 severity among 74,244 subjects who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing in South Korea. Our results suggest that physicians should exercise extra care and give more attention to COVID-19 patients with preexisting NAFLD.8

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dedicated health care professionals treating patients with COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service of Korea for sharing invaluable national health insurance claims data. Data are available on reasonable request from DKY (corresponding author; yonkkang@gmail.com).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (NRF2019R1G1A109977913).

References

- 1.Fan Z., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1561–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim M.S., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1970–1972.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin Y.H., et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boursier J., et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S.W., et al. Gut. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S.W., et al. Gut. 2021;70:76–84. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S.W., et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2262–2271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leiman D.A., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1310–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]