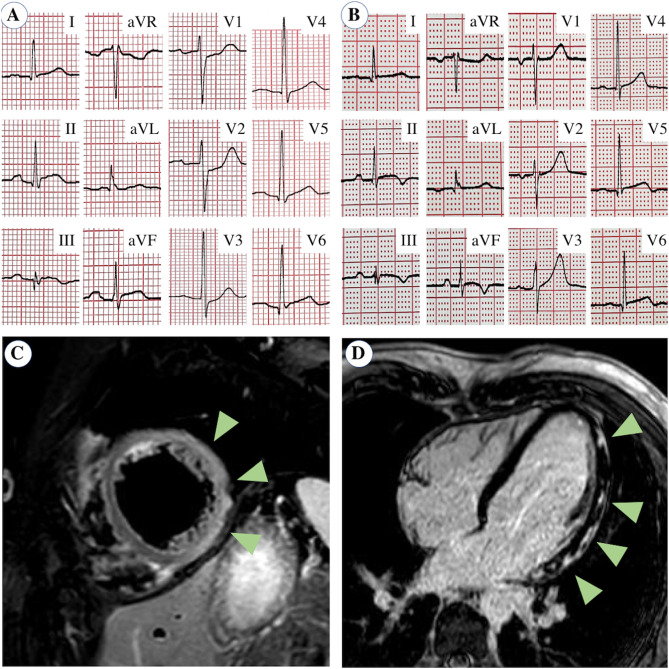

A 24-year old male nurse presented to the emergency department complaining of chest pain with onset 24 hours earlier. He reported no past medical history and no cardiovascular risk factors apart from e-cigarette smoking. He received the second dose of COVID-19 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine 60 hours before the onset of chest pain exacerbated by deep breathing and being in a supine position. The chest pain was exacerbated by deep breathing and the supine position. It radiated to the back and the left arm and was responsive to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, mild ST-elevation in inferior leads, and mild ST-depression in leads V1 to V3 (Figure 1 A). The echocardiogram showed mildly reduced left ventricle ejection fraction (EF 45%) with inferior-posterior wall hypokinesia and hyperechogenicity of the pericardium without effusion. With a diagnosis of suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the patient was referred to the hub hospital for urgent coronary angiography, which showed a normal coronary tree. Laboratory analyses revealed elevated cardiac-specific markers (high-sensitive cardiac troponin T 1204 ng/L, creatine kinase-MB 79 UI/L; normal <14 and <25, respectively), high C-reactive protein (1.9 mg/dl; normal <0.5) and normal blood count (white blood cells 9300/mm3, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio 3.8). SARS-CoV-2 swab was negative, while antibodies against SARS-CoV2-2 were present (IgM 3.8, IgG 56.1; negative <1). The cardiac magnetic resonance performed the day after admission showed a mildly dilated left ventricle with normal EF and no regional kinesis abnormalities. On the T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery imaging, an increase in the myocardial signal intensity was evident in the inferior, inferolateral, and anterolateral walls. Furthermore, late gadolinium enhancement imaging demonstrated patchy areas of hyper-enhancement with a non-ischemic subepicardial distribution, thereby fulfilling the updated Lake Louise criteria for myocardial inflammation (Figure 1C and D).1 Anti-inflammatory therapy was prescribed, resulting in pain relief. Serological tests for the detection of antibodies against the common causes of myocarditis were all negative. During hospitalization, the ECG showed a slow evolution of repolarization abnormalities, with T-wave inversion in inferior leads and normalization of ST-segment in the anterior and inferior leads (Figure 1B). No Q-wave developed. Continuous ECG monitoring showed only isolated premature ventricular contractions. The patient was discharged after one week in good condition, with troponin and inflammatory markers within normal ranges.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance. (A) Electrocardiogram at admission showed mild ST-segment elevation in inferior leads (II, III, aVF) and mild ST-segment depression in V1 to V3. (B) At discharge, ST-segment was normalized but T-wave inversion occurred in inferior leads. (C) On cardiac magnetic resonance, T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery sequence showed myocardial signal intensity increase (edema) in inferior, inferolateral and anterolateral walls (arrows). (D) Late gadolinium enhancement imaging demonstrated patchy areas of hyper-enhancement with non-ischemic subepicardial distribution (arrows).

Our case describes an episode of acute myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Notably, it was a “usual” case of myocarditis, with an ACS-like presentation and a favorable course in terms of left ventricle function and arrhythmias. The causal relation between vaccination and myocarditis is strongly supported by their strict temporal relationship.

In general, immunization-related myocarditis is rare and mainly occurs after vaccination against smallpox. Usually, it occurs 10 days after vaccination without life threatening complications.2, 3 The exact immunological mechanisms linking vaccination and myocarditis are unknown. Experimental evidence suggests that a type III hypersensitivity mediated by immunocomplexes could play a role.4 Moreover, the activation of the antigen-presenting cells is crucial in preclinical models of myocarditis. In humans, pro-inflammatory triggers such as vaccination or infections can overwhelm the self-tolerance mechanism inducing heart-specific autoimmunity.5

In conclusion, similar to other types of vaccinations, myocarditis may also occur after administering the vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Clinicians must be aware of this possible complication, but by no means should this rare adverse event discourage the practice of this essential preventive strategy.

Authors’ contribution

All authors were involved in the care and management of the patient as well as in writing, editing, and finalizing the manuscript. Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferreira V.M., Schulz-Menger J., Holmvang G., et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3158–3176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuntz J., Crane B., Weinmann S., et al. Myocarditis and pericarditis are rare following live viral vaccinations in adults. Vaccine. 2018;36:1524–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckart R.E., Love S.S., Atwood J.E., et al. Incidence and follow-up of inflammatory cardiac complications after smallpox vaccination. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aslan I., Fischer M., Laser K.T., et al. Eosinophilic myocarditis in an adolescent: a case report and review of the literature. Cardiol Young. 2013;23:277–283. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112001199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson U., Kurrer M.O., Sonderegger I., et al. Activation of dendritic cells through the interleukin 1 receptor 1 is critical for the induction of autoimmune myocarditis. J Exp Med. 2003;197:323–331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]