Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the major threatening diseases worldwide, being the third most common cancer, and a leading cause of death, with a global incidence expected to increase in the coming years. Enhanced adiposity, particularly visceral fat, is a major risk factor for the development of several tumours, including CRC, and represents an important indicator of incidence, survival, prognosis, recurrence rates, and response to therapy. The obesity-associated low-grade chronic inflammation is thought to be a key determinant in CRC development, with the adipocytes and the adipose tissue (AT) playing a significant role in the integration of diet-related endocrine, metabolic, and inflammatory signals. Furthermore, AT infiltrating immune cells contribute to local and systemic inflammation by affecting immune and cancer cell functions through the release of soluble mediators. Among the factors introduced with diet and enriched in AT, fatty acids (FA) represent major players in inflammation and are able to deeply regulate AT homeostasis and immune cell function through gene expression regulation and by modulating the activity of several transcription factors (TF). This review summarizes human studies on the effects of dietary FA on AT homeostasis and immune cell functions, highlighting the molecular pathways and TF involved. The relevance of FA balance in linking diet, AT inflammation, and CRC is also discussed. Original and review articles were searched in PubMed without temporal limitation up to March 2021, by using fatty acid as a keyword in combination with diet, obesity, colorectal cancer, inflammation, adipose tissue, immune cells, and transcription factors.

Keywords: diet, inflammation, immune cells, fatty acids, adipose tissue, obesity, colorectal cancer, transcription factors

1. Introduction

The global incidence of overweight/obesity is expected to reach 20% by 2025 and represents a major health problem, afflicting currently adults and children worldwide [1]. It represents a considerable cost to public health and a clinically urgent issue for the population in several countries [2,3]. Excess adiposity is associated with increased incidence of several cancers, including colorectal cancer (CRC), and represents an important indicator of survival, prognosis, recurrence, and response to therapy. CRC is the third most common cancer worldwide and a leading cause of death with burden expected to increase in the coming years (IARC 2020. Colorectal cancer. Source: Globocan. The Global Cancer Observatory. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/today, accessed on 30 May 2021). Both genetic background and a range of modifiable environmental/lifestyle factors play a role in CRC aetiology. Specifically, enhanced adiposity, particularly abdominal obesity, is associated with increased CRC incidence, and cancer risk is highly modifiable by diet. White adipose tissue (AT), where diet-delivered signals converge, is now recognized as the largest endocrine organ and plays a key role in metabolic and immune homeostasis [4]. To date, several studies have investigated the role of diet/nutrition in CRC showing both a causal and protective role in tumour development [5].

In addition of being an established risk factor for CRC [6], enhanced adiposity is also associated with worse outcomes [7,8], although the detrimental relationship between obesity and CRC is complex and not yet precisely defined. In this regard, it has been postulated that the production, by AT, of a large spectrum of adipocytokines and metabolites, showing proinflammatory and cancer prone features, is of great importance. Furthermore, obesity-related metabolic alterations (i.e., metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, lipid metabolism impairment, endocrine changes and oxidative stress) may promote CRC occurrence and progression [9].

Diet and excess adiposity can also affect cancer development by influencing tumour surveillance and shaping the host immune response [10]. Indeed, white AT is now recognized as the largest endocrine organ where signals from diet converge, playing a key role in both metabolism and immune system homeostasis [9,11]. Furthermore, a whole set of immune cells, with either proinflammatory (i.e., dendritic and mast cells, M1 macrophages, neutrophils, Th1 CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes, and B cells) or antiinflammatory (i.e., M2 macrophages, regulatory T (Treg) cells and Th2 CD4 T lymphocytes, and eosinophils) properties, is held in AT, whose polarization profile depends on the health status of adipocytes [12,13].

Growing evidence indicates that a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, called “meta-inflammation”, occurs in metabolically active tissues, including AT, and characterizes obesity, thus contributing to the impairment of immune cell functions, and representing a key determinant in the development of obesity-related morbidities, including CRC [14]. Indeed, the molecular mechanisms underlying inflammation-promoted tumorigenesis or tumour progression have become an important topic in cancer research, and the crucial importance of the AT microenvironment in regulating the dynamic interplay between neoplastic and immune cells has recently emerged [15].

In this regard, fatty acids (FA), introduced with the diet and processed/released by AT, are gaining importance as main actors in this interplay for their capacity to influence both cancer cell proliferation and the host immune response [16]. Depending on their chemical features, FA can exhibit either pro- or anti-inflammatory activity [17,18]. In general, long-chain saturated fatty acids (SFA) have been associated with inflammatory effects while short-chain fatty acids, derived from microbial fermentation of indigestible foods, exert anti-inflammatory actions [19]. Likewise, ω6 and ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) have been associated with inflammatory or anti-inflammatory pathways, respectively [20]. This is accomplished through several mechanisms, by controlling the activation of either cell surface or intracellular receptors, and regulating signal transduction, gene expression, and the nuclear abundance of transcription factors (TF) [17,18,21]. By virtue of their properties, FA have the potential to control host surveillance mechanisms and shape anticancer responses by directly influencing both innate and adaptive immunity and by regulating AT immune and metabolic homeostasis.

The following sections provide an overview of the changes of FA profiles in human AT occurring in obesity and in CRC and of the role played by FA as regulators of inflammation and immune responses, focusing on the molecular mechanisms and TF involved. Non-homogeneous and sometimes contradictory results were found due to the different fat depots analysed or different FA doses and treatment times in intervention studies. Nevertheless, the type of effect (inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory) of specific FA classes was confirmed in all in vitro and in vivo studies. The potential of these molecules to act as a link among diet, AT inflammation, and CRC development is discussed.

2. Fatty Acid Profiles in Obesity and Colorectal Cancer and Their Relationship with Dietary Intake

The body fat mass is distributed in two main fat depots, visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous (SAT) white AT, whose anatomical distribution is influenced by several factors, including age, sex/gender, and nutrition [22]. When energy balance is shifted toward obesity, AT undergoes profound modifications such as adipocyte hyperplasia, tissue remodelling, changes in FA composition, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction [23]. A preferential accumulation of SFA and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) have been described for SAT and VAT, respectively, in obese individuals, despite a comparable PUFA composition [24,25]. However, the changes in FA composition occurring in obese subjects with respect to normal-weight individuals have been only poorly explored. We reported a marked decrease of the ω3/ω6 PUFA ratio in VAT of obese as compared to lean subjects, despite comparable total content of SFA, MUFA, and PUFA [26]. By analysing the ω6 PUFA family members, a selective increase of the proinflammatory arachidonic acid (AA) and parallel decrease of the anti-inflammatory γ linolenic acid (GLA) was unravelled in obese subjects [27]. Palmitoleic (POA) and stearic (SA) acids were also found enriched in SAT and VAT of obese versus lean individuals, in association with a higher stearoyl-CoA-desaturase 1 (SCD1) index [28,29]. Furthermore, an increase in circulating free FA have been reported in obesity as a consequence of enhanced release by the enlarged AT mass [30,31].

Although these findings suggest that the altered FA processing and conversion rate can contribute to changing FA profiles in obesity, there is strong evidence that FA content in AT mirrors their relative abundance in the diet. A significant correlation between dietary FA intake and FA composition of AT was demonstrated in obese individuals, in particular for oleic (OA), linolenic (LA), and α-linoleic (ALA) acids, and for total ω6 PUFA [32]. Interestingly, visceral obesity was positively associated with ω6 PUFA and inversely associated with MUFA and ω3 PUFA content in AT [25]. Furthermore, in a large Swedish cohort study, the relative proportion of some PUFA (i.e., LA, ALA, eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA, and docosahexaenoic acid, DHA), MUFA (i.e., POA), and SFA (i.e., palmitic acid, PA) in SAT was found to reflect their dietary intake [29,33,34]. Accordingly, we recently reported that the higher AA content detected in the VAT of obese subjects is associated with a higher intake [27,29]. Similarly, higher levels of OA were found in SAT of overweight subjects consuming MUFA-compared to SFA-rich diets [35]. Thus, changing the nature of the fat consumed may alter FA composition of AT and has a profound influence on the type of FA available to the body [36]. Furthermore, unhealthy dietary habits may influence AT-associated and circulating FA profiles contributing to the alteration of metabolic pathways [29,34]. Under obese conditions, AT also expresses high levels of FA synthase, an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of FA from dietary carbohydrates, which in turn induces inflammation [37].

A number of studies analysing the AT composition in CRC-affected individuals have described alterations of FA metabolism and profiles in different fat depots and specific FA profiles have been correlated with the risk of developing CRC [38,39].

As reported for obese subjects, an unbalanced ω3/ω6 PUFA ratio and accumulation of proinflammatory ω6 PUFA (mostly dihomo-γ-linolenic acid DGLA and AA) in AT take place also in CRC subjects, even though differences were described depending on the relative abundance of individual PUFA and fat depots involved [27,40,41,42]. Specifically, by comparing VAT and SAT FA profiles in colon cancer (CC) patients it was evidenced that FA composition of SAT is only slightly affected, while a significant decrease of the ω3 PUFA ALA and stearidonic acid (SDA), along with increased DGLA and AA content, occurs in VAT [41]. Changes in the ω3/ω6 PUFA profile (higher DGLA and docosapentaenoic acid, DPA, versus lower ALA) were conversely reported in SAT from CRC patients in a different study, in association with markers of systemic inflammation [42]. Moreover, an increase of total SFA and MUFA content was associated with CRC [41]. In contrast, some old studies failed to reveal any change in the relative abundance of the different FA in cancer subjects [43,44].

Furthermore, we reported alterations in VAT FA profiles in CRC, highlighting differences between lean and obese patients [26,27,29]. Specifically, we evidenced a decrease in the ω3/ω6 PUFA ratio and an increased content of DGLA and docosatetraenoic acid (DTA) in cancer patients, irrespective of body weight [26,27]. However, when obese and normal weight patients were compared, accumulation of AA was selectively observed in obese CRC subjects with respect to healthy individuals. Conversely, lean patients were found to be characterized by reduced SFA content despite a higher dietary intake [27,29]. The enrichment in proinflammatory FA observed in cancer patients is associated with constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 activation in adipocytes and enhanced release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [27].

Changes in lipid metabolism in AT has also been related to tumour progression [45]. In particular, MUFA content in visceral peritumoral fat of CRC patients was associated with advanced disease, whereas similar levels of SFA and PUFA were found irrespective of the tumour stage [45]. At the same time, the SAT content of MUFA has been negatively associated to the risk of developing CC in epidemiological studies [46], highlighting that the same category of FA (e.g., MUFA) can play different roles in cancer onset/progression depending on the timing and type of AT [45,46].

As with obese individuals, the levels of circulating free FA have been recently found to be increased in CRC patients and associated with cancer risk [47]. Conversely, CRC risk has been inversely correlated to dietary PUFA intake. A growing body of epidemiological evidence has linked to ω3 PUFA-rich diets or ω3 PUFA dietary supplementation to a potential lower risk of CRC, and a recent study definitely correlated fish intake and dietary intake of individual and total ω3 PUFA with lower incidence of CRC [48].

In conclusion, the altered ω3/ω6 PUFA balance in AT and the enrichment in SFA reported in most studies seems to be a common feature of obese and CRC-affected subjects. This could markedly affect the function of AT and distal tissues, such as the intestinal epithelium, as a result of an increased ω6 PUFA-mediated inflammation and a reduced protective effect of ω3 PUFA. The changes in FA profiles in different fat depots sustain proinflammatory microenvironment in CRC patients, supporting a role for both unbalanced dietary intake and alterations in FA metabolism and storage in colorectal tumorigenesis.

3. Fatty Acids and Adipose Tissue Homeostasis

The importance of AT in controlling systemic inflammation has been pointed out in recent years. Due to its endocrine character, alterations in this tissue may lead to various metabolic disorders such as diabetes, cardiovascular and liver diseases, and cancer. The recognition that AT not only synthesizes and stores FA but also releases these compounds, together with a large number of other active factors able to act in an autocrine and paracrine manner [13], has provided a conceptual framework, which helps to understand how unhealthy diets and obesity contribute to the development of several disorders affecting distal organs and tissues.

People with obesity exhibit a general proinflammatory profile. Changes of cytokine/adipokine secretion by adipocytes and free FA release by AT couple with dramatic changes in the immune cell repertoire and function shifting the balance of cell subsets and soluble mediators toward a proinflammatory profile [49,50,51]. This results from an altered balance of key transcription factors able to promote inflammation through the induction of molecules such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4. These, in turn, exacerbate the inflammatory state [52,53,54] and can promote a favourable microenvironment to CRC onset/evolution [55].

SFA have been shown to negatively affect metabolic functions [56] and to activate inflammatory pathways by acting as ligands of receptors, such as the TLR, involved in the innate immune response. Conversely, endogenous or dietary PUFA are precursors of both pro- and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators [57].

Studies carried out on in vitro models have evidenced the ability of SFA to induce an inflammatory response in AT through the TLR/NF-κB pathways. At the same time, adipocytes from SAT and VAT of obese subjects, treated with free FA (i.e., OA, LA, AA, lauric and myristic acids or PA and SA mixtures) showed a proinflammatory cytokine profile [58,59]. Conversely, ω3 PUFA, in particular DHA and EPA, were reported to exert an anti-inflammatory role in whole SAT and VAT and in isolated adipocytes from obese subjects by reducing proinflammatory mediators [60,61,62]. These data are in line with our studies demonstrating the capacity of DHA to downregulate STAT3 activation and IL-6 secretion, and to increase adiponectin expression, in VAT adipocytes [26,27]. On the contrary, AA exposure results in a significant STAT3 activation and concomitant downregulation of PPAR-γ expression [26,27]. The capacity of pro- and anti-inflammatory PUFA to regulate immune pathways in VAT suggests a role for the altered PUFA composition in shaping immune cell phenotypes in obesity [63]. Ω3- and ω6-PUFA, in particular DHA and AA, have also been demonstrated to differently influence the adipocyte transcriptional program in normal-weight and obese subjects [61,62,64], acting on genes involved in AT inflammation and metabolism [64,65]. The ability of dietary PUFA to regulate adipocyte gene expression further elucidates the role of diet in the modulation of AT inflammation, even though the mechanisms responsible of such an effect still need to be clarified.

Several intervention studies have also investigated the role of FA in the control of AT homeostasis. Discordant results have been reported mainly due to the dose and timing of FA supplementation, the different populations investigated, and differences related to the type of body fat depot analysed. Nevertheless, the beneficial role of ω3 PUFA consumption on a wide range of AT inflammatory responses have been undoubtedly highlighted. In a clinical trial of obese participants, ω3 PUFA-rich fish oil (FO) supplementation was found to reduce the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome associated genes in AT and circulating IL-18 levels [62]. Accordingly, a meta-analysis including 17 studies revealed that FO supplementation is associated with increased insulin sensitivity among people with metabolic disorders [66], likely by decreasing the levels of TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6. The same conclusion was obtained in a pilot study carried out on 32 overweight and/or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who received FO supplementation [67]. Among the genes modulated by the consumption of different PUFA sources are those involved in AT inflammation and metabolism, including inflammasome-associated IL-18, IL-1β and IL-1RN, and genes involved in impaired fasting glucose in obese subjects [62,68]. Moreover, in a clinical trial (FFAME) involving healthy volunteers and based on EPA and DHA supplementation, ω3 PUFA showed immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory action during AT inflammation induced by experimental endotoxemia [61,69]. Changes in the expression of genes related to inflammation and the immune response were also observed in SAT from overweight/obese women supplemented with EPA and/or lipoic acid and subject to weight loss and dietary interventions [70]. Conversely, no effect on SAT inflammatory genes was exerted by DHA supplementation in obese postmenopausal women [71].

A strong association between AT inflammation and its SFA and MUFA content was also demonstrated [24]. KOBS study carried out on obese individuals showed that surgery-induced weight loss reduces the expression of inflammatory pathways (IL-1β and NF-κB), and unravelled a positive/negative association between inflammation and SFA and MUFA content, respectively, in both SAT and VAT [20]. FADS1/FADS2 genotypes were found able to modify these correlations, both in KOBS and DiOGenes studies, indicating that variants in this gene cluster may influence the interaction between AT FA and tissue inflammation [24,72].

4. Fatty Acids and Immune Cells: Regulation of Transcription Factors, Inflammatory Pathways, and Effector Functions

Obesity is associated with increased numbers and activation levels of specific immune cell subsets responsible for skewing the balance towards a proinflammatory status. AT-associated active molecules, including FA, may represent important determinants in shaping the immune cell phenotype and tissue microenvironment. In particular, the balance of saturated/unsaturated FA and the relative composition of ω3/ω6 PUFA may have significant consequences on immune system homeostasis, acting as an important link between unhealthy dietary habits/obesity and impaired cancer surveillance [73,74,75].

Although only a few studies have focused on FA-mediated immune cell regulation in the context of human AT, the immunomodulatory effects of dietary FA on cells of both innate and adaptive immunity have been investigated in a number of in vivo studies and in in vitro and animal models [76]. The molecular mechanisms and pathways involved are still poorly understood and often present cell type-specific features.

In this section we discuss the human studies that highlighted the immunomodulatory properties of FA following their dietary supplementation and after in vitro/ex-vivo stimulation of immune cells, focusing on the molecular pathways involved.

4.1. Effects of Dietary Fatty Acid Supplementation on Blood Immune Cell Gene Expression Profiles

The role of FA in the regulation of immune/inflammatory responses has been investigated in several intervention studies aimed at assessing the effects of consumption of different FA on inflammation-related genes. As discussed above, the analysis of inflammatory response gene expression profiles in AT have generated discordant results mainly due to differences related to the type of body fat depot analysed. Conversely, gene expression profiling of circulating immune cells within the peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) fraction turned out to have the potential to clarify the molecular effects of FA consumption on human health [77]. In dietary intervention studies, PBMC gene expression profiles have been shown to act as potential biomarkers reflecting metabolic changes in the liver and AT [78,79]. Furthermore, they can reflect metabolic changes due to long-term nutritional adaptation thus mirroring the individual physiologic or pathologic state [78].

In recent studies exploiting whole genome transcriptional approaches on PBMC (Table 1), annotation and pathway analysis have shown that the supplementation of ω3 PUFA-rich oils modulates the expression of genes involved in inflammatory pathways, such as eicosanoid synthesis, interleukin signalling, oxidative stress response, cell cycle, cell adhesion, apoptosis, scavenger receptor activity, and DNA damage, thus confirming and shedding further light on the anti-inflammatory/antioxidant role of dietary ω3 PUFA [80,81]. Conversely, SFA intake was confirmed to be associated with postprandial upregulation of genes involved in proinflammatory pathways [17].

Table 1.

The main intervention studies evaluating the effects of fatty acid (FA) on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) gene expression.

| Dietary Compound/FA | Subjects | Treatment Duration and Doses | Genes/Pathways Targeted | TFs Involved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ω3 PUFA | Metabolically healthy overweight and obese subjects | 6 weeks 3 g/day |

↓Oxidative stress response | NRF2, PPAR-α, HIF, NF-κB | [82] |

| ω3 PUFA | Insulin-resistant obese subjects | 8 weeks 1.8 g/day |

NRF2, PPAR-α, HIF, NF-κB | [83] | |

| ω3 PUFA | Obese women | 3 months | ↑Lipid metabolism ↑Antioxidant enzymes |

↑PPAR-α, NRF2 | [84] |

| FO | Alzheimer disease subjects | 6 months 1.7 g/day DHA, 0.6 g/day EPA |

↓Neuro-inflammation | [85] | |

| FO | Elderly subjects | 26 weeks 0.4–1.8 g/day EPA + DHA |

↓Eicosanoid synthesis ↓TLR/Interleukin/MAPK signalling ↓Oxidative stress ↓Cell adhesion ↓Hypoxia signalling |

↓NF-κB ↑PPAR/LXR/RXR |

[86] |

| HOSO | 26 weeks | 4.0 g/day ↓Eicosanoid synthesis ↓Interleukin/MAPK signalling |

|||

| FO | PCOS women | 12 weeks 2.0 g/day |

↓IL-1, CXCL8 | ↑PPAR-γ | [87] |

| EPA + DHA | Healthy subjects with moderate hypertriglyceridemia | 8 weeks 0.85 g/day and 3.4 g/day |

No effects on inflammatory and endothelial function | [88] | |

| FO | CHD patients | 8 weeks | No effects on inflammatory and endothelial function | [68] | |

| FO | Healthy lean subjects | 7 weeks 8 g/day |

↑ER stress response ↑Apoptosis ↑Cell cycle regulation ↑Antioxidant response |

↑ 35 TF (i.e., ATF4, MIF1, E2F, TP53, STAT1, FOXO4, SP1, NRF2) | [89] |

| Krill oil | Healthy subjects | 8 weeks 4 g/day |

↓Glucose metabolism ↓Lipid metabolism ↓Inflammation ↓β-oxidation |

↓ SREBF2 ↓LXRα |

[90] |

| HOSO | 8 weeks | 4 g/day ↓Lipid metabolism ↓Inflammation |

↓LXRα ↓PPAR-δ |

||

| PUFA (40% DHA) | Healthy males | 6 h | ↓Inflammation ↓LXR signalling ↑Cellular stress response |

↓LXR ↓SREBF1 |

[91] |

| SFA | ↑Inflammation | ↑LXR signalling ↓Cellular stress response ↑LXR ↑SREBF1 |

|||

| CSO | Impaired fasting glucose subjects | 12 weeks | ↓Inflammation ↓IFNG |

↑PPAR-γ | [68] |

| ALA | Obese subject | 12 weeks 4.0 g/day |

↓Inflammation | ↑PPAR-γ | [92] |

| Flaxseed oil | T2DM subjects with CHD | 12 weeks 400 mg ALA twice a day |

↓Inflammation | ↑PPAR-γ | [93] |

| ω6 PUFA | Healthy subjects | 8 weeks 12.9 g/day |

↓Lipid metabolism (i.e., LDLR, ABCG, SREBF1, and FASN) ↓Inflammation (i.e., IRAK1, TNFSF1, TLR4, GATA3, IL2RG, and CD8A) |

↓PPAR-δ ↓LXRA |

[80] |

↑ Increases; ↓ decreases; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2; PPAR-α, peroxisome proliferator activated receptors-α; HIF, hypoxia incucible factor, NF-kB, nuclear transcription factor kappa B; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α; FO, fish oil; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; TLR, toll-like receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; LXR, liver X receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; HOSO, high-oleic acid sunflower oil; IL1β, interleukin-1β; CXCL8, C-X-C motif ligand 8; ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; MIF1, macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1; E2F, elongation factor 2F, TP53, tumour protein 53; STAT1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; FOXO, fork-head box O; SP1, specificity protein 1; SREBF, sterol regulatory element-binding factor; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; SFA, saturated fatty acids; CSO, camelina sativa oil; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; CHD, coronary heart disease; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; ABCG, ATP binding cassette-G; FASN, fatty acid synthase; IRAK1, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases; TNFSF1, tumour necrosis factor superfamily 1; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; GATA3, GATA-binding protein 3; IL2RG, IL2 receptor common gamma chain.

More generally, high-MUFA and high-ω3 PUFA diets result in anti-inflammatory PBMC gene profiles, or at least less pronounced proinflammatory responses as compared to SFA consumption.

Specifically, the effects of ω3 PUFA intake on PBMC gene expression have been investigated in two studies including either metabolically healthy overweight and obese individuals or insulin resistant obese subjects [82,83]. The supplementation for 6–8 weeks resulted in consistent changes in the oxidative stress response mediated by erythroid-derived nuclear factor like 2 (NRF2), PPAR-α, hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), and NF-κB signalling pathways [82,83]. Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory effects of ω3 PUFA on circulating immune cells were gender-related and were observed despite any change in serum inflammatory markers [82]. Conversely, a longer (three-months) supplementation with ω3 PUFA in women with obesity was found to decrease the plasma concentrations of several inflammatory markers [84]. Contextual microarray analysis of PBMC demonstrated positive effects on αα target genes related to lipid metabolism and on NRF2-regulated antioxidant enzymes [84]. In line with this evidence, negative effects of fish and vegetable oil (ω3 PUFA- and MUFA-rich, respectively) supplementations on PBMC inflammatory pathways have been also demonstrated in elderly individuals [86], in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease [85], and in a cohort of women with polycystic ovary syndrome [87], thus further highlighting the role of ω3 PUFA intake in redirecting immune responses in conditions where chronic inflammation plays a pathogenic role. Conversely, some other studies failed to demonstrate any change in the expression of inflammatory genes in PBMC after supplementation with either nutritional doses or high pharmacologic doses of EPA and DHA [88], or after fatty fish intake [68]. The gene expression program of healthy individuals is also strongly influenced by dietary FA intake. Several intervention trials with healthy lean subjects highlighted extensive gene expression modulation in PBMC following FO [89]. Among these genes are those involved in cell cycle and apoptosis [89], in glucose and β-oxidation [90] or in lipid metabolism and inflammation [86,90], and NRF2 target genes exhibiting antioxidant properties [89].

Other dietary intervention studies based on vegetable oils, such as flaxseed oil and camelina sativa oil, which are enriched in ALA, have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects on PBMC gene expression. In particular, a significant increase in PPAR-γ levels has been reported in individuals with impaired fasting glucose and in obese and T2DM subjects [68,92,93]. Furthermore, the expression of several genes involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation was favourably changed in PBMC when replacing SFA-rich with ω6 PUFA-rich diets [80].

According to the effects on gene expression described in most studies, ω3 PUFA supplementation was reported to shift the effector functions of specific immune cell populations within the exposed PBMC toward an anti-inflammatory profile [94,95]. Reduced natural killer cell activity and T lymphocyte proliferation in mitogen-stimulated PBMC was observed following a 12-week FO intake in healthy individuals [94]. A comparable negative effect on lymphocyte proliferation was observed following intake of moderate levels of the anti-inflammatory ω6 PUFA GLA [95], thus suggesting that these PUFA have the capacity to control excessive immune cell activation that could have deleterious effects and lead to immunosuppression.

4.2. Effects of In Vitro Fatty Acid Exposure on Immune Cell Functions

A number of in vitro studies have confirmed the regulatory effects of ω3 PUFA on immune homeostasis/inflammation and have highlighted the capacity of the different classes of FA to modulate the biology of human cell populations participating to both innate and adaptive immune responses, and actively involved in tumour surveillance.

These studies (summarized in Table 2) had the advantage to directly relate the effects of single FA treatment to a specific cell subset and allowed an in-depth understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved. FA were shown to regulate different functions, depending on the cell type, through the modulation of gene expression and by regulating the activity of different families of TF, mainly including PPAR (α, β, and γ), LXR, SREBP, and NF-κB [96,97].

Table 2.

In vitro studies evaluating the immunomodulatory effects of fatty acid (FA) on immune cells.

| Dietary Compound/ FA |

Cell Type | Downstream Effects | Pathway(s) Targeted | TFs Involved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFA | |||||

| PA | THP-1 Primary monocytes |

↑IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, TNFα, CCL2, CCL4, CXCL8 | ↑TLR4/MyD88/MAPK | ↑NF-kB, AP-1 | [98,99,100,101] |

| PA (in combination with TNFα) | THP-1 Primary monocytes/macrophages |

↑CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL8 | ↑TLR4/TRIF | ↑NF-kB, AP-1, IRF3 | [102,103,104] |

| PA | THP-1 | ↑IL-1β | ↑TLR2/TLR1 ↑NLRP3 inflammasome |

[105] | |

| PA | MDDC | ↑IL-1β ↑ROS ↑Activation/maturation |

↑TLR4/MD-2 ↑NLRC4 Inflammasome |

↑NF-kB | [106] |

| SFA | MDDC | No effects on inflammation | [107,108] | ||

| OA, LA, GLA | Neutrophils | ↑ROS | [109] | ||

| PA | PBMC | ↓NNT ↑ROS ↑Th17-type cytokines |

[110] | ||

| PA | Naïve T lymphocytes | ↑SLAMF3 | ↑PI3K/AKT | ↑STAT5 | [111] |

| MUFA | |||||

| OA | Neutrophils | ↑Phagocytosis and killing ↑ROS ↑IL-1β, CXCL3, VEGF |

↑Intracellular calcium ↑PKC |

[109,112] | |

| OA | T lymphocytes |

↓IFNγ ↑IL-4, IL-10 |

[113] | ||

| POA | ↓ConA-induced T lymphocyte proliferation | ↓Treg cell differentiation ↓IL-2, IL-6, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-17A ↓CD28 externalization |

↓NFAT, AP-1, NF-κB | ||

| Albumin-bound OA | PBMC-sorted Treg cells | ↑Treg cell survival | [114] | ||

| ω6 PUFA | |||||

| AA | Neutrophils | ↑ROS ↑TNFR1, TNFR2 |

↑Intracellular calcium ↑PKC, ERK1/2, cPLAP2 |

[112,115] | |

| ω6 PUFA | Neutrophils | ↓ATP ↑LDH release ↑Mitochondria depolarization |

[116,117] | ||

| AA | THP-1 Primary monocytes |

↓IFNγ signalling pathway ↓IDO |

↓STAT1 phosphorylation | [118] | |

| AA | Differentiating MDDC | ↓CD40, CD80, MR ↓LPS-induced CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86 ↓IL-12p40, TNFα ↓T cell proliferation ↓IL-2/IFNγ in co-cultured T cells |

NF-κB independent | [108] | |

| A1AT-LA | Neutrophils | Anti-inflammatory | ↓IL-1β | ↑PPAR-γ | [119] |

| ω3 PUFA | |||||

| EPA/DHA | THP-1 | ↓IL-1β, IL-18, TNFα, PAI-1 | ↓NF-κB | [62,100,120,121] | |

| EPA/DHA | U937 | M2 polarization | ↑p38 MAPK | ↑KLF4 | [122] |

| EPA/DHA | THP-1 | ↓LPS-induced cytokine gene expression (i.e., IL6, TNFα, IL1β, MCP1, TNFAIP3, and PTGS2) | [123] | ||

| DHA | MDM | Anti-inflammatory | Via GPR120 ↑cPLAP2 ↑PGE2 signalling |

[120] | |

| EPA/DHA | THP-1 | Anti-inflammatory | Via GPR120/GPR40/β-Arrestin-2 ↓NLRP3 inflammasome |

[62,124] | |

| EPA/DHA | MDDC | ↓Cell activation and cytokine production ↓MHC-II, CD40, CD80, CD86, CD83 ↓TNFα, IL-10, IL-12 ↓IL-2/IFNγ in co-cultured T cells ↓T cell stimulation |

↓p38 MAPK | ↑PPAR-γ | [107,125] |

| DHA | Differentiating MDDC |

↑MHC-II ↓IL-12p70, IL-6, IL-10 ↓T cell stimulation |

PPAR:RXR | [126] | |

| EPA/DHA/ ALA |

MDDC | ↓CD1a+ cells ↓IL-6 |

↓GPR120 | [127] | |

| EPA | Differentiating MDDC | ↓CD40, CD80, MR ↓LPS-induced CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86 ↓IL-12p40, TNFα ↓T cell proliferation ↓IL-2/IFNγ in co-cultured T cells |

NF-κB independent | [108] | |

| Oxidized EPA | Monocytes Neutrophils |

↓Adhesion to endothelial cells | ↑PPAR-α | [128] | |

| ω3 PUFA | Neutrophils | ↑Chemotaxis, ROS production, NADPH-oxidase activation | ↑GPR84 | [129] | |

| OA/ALA/DHA | PBMC | ↓LPS-induced inflammatory genes (IL-6, TLR2, TNFα, COX2) | ↓NF-κB | [130] | |

| EPA/DHA | PBMC | ↓CD4+ T lymphocyte produced IL-2, TNFα, IL-4 | ↑PPAR-γ | [131] | |

↑ Increases; ↓ decreases, SFA, saturated fatty acids, PA, IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-18, interleukin-18; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; APK, /TRIF, Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor; MD-2, myeloid differentiation factor 2; NF-kB, nuclear transcription factor kappa B; AP1, activator protein 1; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3; PAI-1,plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; NLRC4, NLR family CARD domain containing 4; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NNT, nucleotide nicotinamide transhydrogenase; SLAMF3, signalling lymphocytic activation molecule family 3; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; MUFA, monounsaturated fat acids; OA, oleic acid; ALA, α-linoleic acid; LA, linolenic acid; GLA, γ linolenic acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; POA, palmitoleic acid; AA, arachidonic acid; A1AT, alpha1-antitrypsin; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; TNFR, tumour necrosis factor receptor; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; MCP1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1; TNFAIP3, TNF-alpha-induced protein 3; PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; GPR120, G protein-coupled receptor 120; cPLAP2, plastid-lipid-associated proteins; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; GPR120/GPR40, G protein-coupled receptor 120/40; MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II; p38 MAPK, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; KLF4, Kruppel-like factor 4; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptors; RXR, retinoid X receptors; MDDC, monocyte-derived dendritic cells; MDM, monocyte-derived macrophages; NNT, nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase.

4.2.1. Innate Immunity Cells

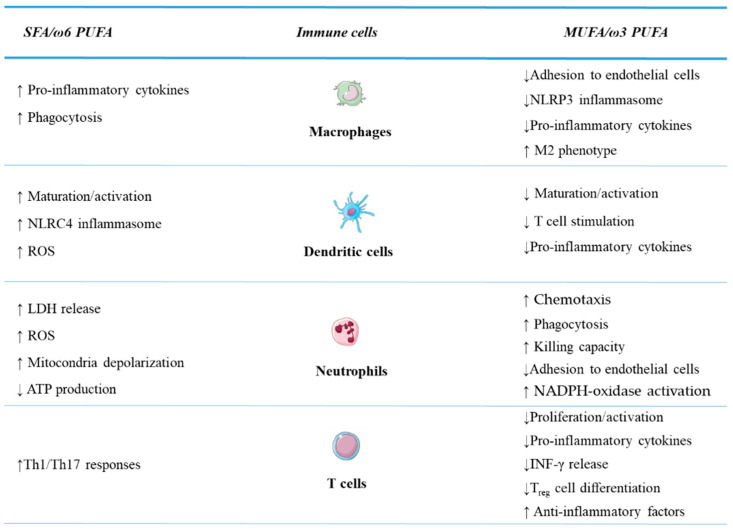

The immune cell populations involved in inflammatory response and contributing to the early defence against infections, tumours, and metabolic insults have been studied for their responsiveness to dietary FA. To date significant effects have been described for monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and neutrophils and a number of functions have been identified to be differentially regulated by saturated and unsaturated FA. These include: (a) cell activation/maturation, (b) production and secretion of immune mediators, (c) phagocytic/cytotoxic activity, and (d) T cell stimulatory capacity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of fatty acids on immune cell functions.

Monocytic cell lines and primary monocytes exposed to free FA (mostly PA) were shown to exhibit an increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, which is mediated by activation of MAPK and the NF-κB canonical pathway [99,100,101,104,105] or AP-1 [98,104]. Interestingly, PA, in combination with TNFα, stimulates a more marked increase in CCL2 and CXCL8 production as compared with either treatment alone, requiring the TLR4/TRIF/IRF3 signalling cascade [102,103]. Since elevated levels of free PA and TNFα have been reported in obesity, their cross-talk may be a key driver of obesity-associated chronic inflammation via excessive chemokine production.

Similarly, PA was shown to stimulate the production of IL-1β in DC via TLR4/MD-2, through an inflammasome dependent mechanism, ultimately leading to NF-κB activation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and to cell maturation/activation [106]. Other studies, however, failed to demonstrate proinflammatory effects of SFA in DC [107,108]. Furthermore, although TLR4 represents the main receptor involved in the recognition of SFA by myeloid cells [99,102,103,106], Snodgrass and co-authors have reported the capacity of PA to directly activate TLR2, highly expressed on human monocytes, by inducing heterodimerization with TLR1 [105]. PA-dependent TLR2 triggering leads to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion in the THP-1 cell line, while the activation of this pathway does not occur following exposure to other dietary SFA such as myristate and laurate [98].

In vitro models have also been widely used to investigate the effects of FA on neutrophil homeostasis. According to their general proinflammatory activity, dietary SFA were reported to stimulate ROS production in neutrophils [109]. A comparable inflammatory response was generated by MUFA, in particular OA, which was found to enhance phagocytosis, killing capacity and cytokine production in these cells [109,112], and ω6 PUFA, specifically AA, able to enhance ROS production, LDH release, mitochondria depolarization, and lipid accumulation, while reducing ATP production [112,115,116,117]. Conversely, a different member of the ω6 PUFA family, linoleic acid (LA), exerts anti-inflammatory activity in neutrophils [119].

AA was also shown to maintain an inflammatory state in THP1 and primary monocytes by interfering with the IFN-γ signalling pathway, reducing the phosphorylation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1, and ultimately blocking the immunosuppressive activity of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in vivo [118].

The impact of ω3 PUFA on the activation and cytokine/chemokine production of innate immunity cells, and the regulatory mechanisms behind it, have been also extensively investigated. According to the effects observed following dietary supplementation, ω3 PUFA, in particular DHA and EPA, have been reported to exert anti-inflammatory activities on in vitro stimulated monocytic cell lines. This was achieved either through inhibition of the NF-kB pathway leading to reduced expression of proinflammatory mediators [62,100,120,121], or via p38 MAPK-mediated activation of KLF4, resulting in M2 polarization [122]. Moreover, DHA and EPA were found to attenuate cytokine gene expression induced by LPS stimulation in THP-1- and primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) in a synergistic manner [123], and the timing of PUFA stimulation turned out to play an important role [123].

The G protein-coupled receptors (GPR) have been characterized as the ω3 PUFA receptor/sensor in both macrophages and mature adipocytes, involved in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of EPA and DHA [132]. By signalling through GPR120 and GPR40, DHA has been shown to exert an anti-inflammatory activity on THP-1 and primary MDM through several mechanisms, including the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) mediated signalling [120,124].

Similar to macrophages, the functional activation/maturation of DC is reduced following ω3 PUFA exposure [107,108,124,125]. This effect, however, is independent of NF-κB [108] and requires PPAR-γ [125] or PPAR-γ:RXR heterodimers [126]. In this regard, there is considerable evidence that ω3 PUFA modulate the transcription of genes involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation in DC by acting as ligands of PPAR [126] or by regulating the activity of liver X receptors (LXR). Focusing on cellular function, monocyte-derived DC (MDDC) cultures stimulated with DHA, EPA, and ALA exhibit a decreased proportion of activated CD1a+ cells, and reduced expression of IL-6 and GPR120 [127]. Additionally, DHA and EPA downregulate the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and costimulatory molecules on the surface of DC [107,108], and reduce the expression of TNFα and IL-12p40 as compared to PA or OA [108], while MDDC differentiation in the presence of DHA results in increased expression of MHC-II and costimulatory molecules coupled to reduced secretion of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [126]. Other studies have reported the inhibition of cytokine production in EPA- and DHA-treated MDDC, coupled to reduced ability to stimulate activation, proliferation, and IL-2/IFN-γ production in T lymphocytes [108,125], thus suggesting that the immunomodulatory effects of dietary FA on DC may have a significant influence on adaptive immune responses.

ω3 PUFA were also reported to control inflammation in in vitro stimulated neutrophils, and the oxidation status of these FA proved essential in determining their effects. Indeed, oxidized EPA was found to significantly inhibit in vitro neutrophil and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells by blocking endothelial adhesion receptor expression and by activating PPAR-α [128]. Interestingly, a proinflammatory effect of ω3 PUFA on neutrophils has also been reported [129,133]. Specifically, FA-mediated activation of GPR84, abundantly expressed in these cells, triggers inflammatory responses such as chemotaxis, ROS production, granule-localized receptor mobilization, and NADPH-oxidase activation [129]. The latter evidence indicates that different, and even opposite, responses can be stimulated by the same type of FA depending on the cell type, oxidation level, or receptor engaged.

Finally, saturated and unsaturated FA were also shown to differentially influence inflammatory gene expression in LPS-stimulated PBMC [130,131]. MUFA and ω3 PUFA reduce inflammatory gene expression, by influencing NF-κB cell availability and modifying its post-translational regulation. Conversely, SFA and ω6 PUFA elicit minor effects on inflammatory gene expression regardless of LPS stimulation [130].

4.2.2. Adaptive Immunity Cells

According to what was reported for innate immunity cells, saturated and unsaturated FA were shown to exert opposite effects on signalling pathways, gene expression and effector functions of cells participating to adaptive immunity, mostly T lymphocytes (Figure 1). Exposure of naive T lymphocytes to PA was found to induce the expression of signalling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 3 (SLAMF3), a molecule found upregulated in T cells from T2DM patients and associated with their ability to produce IFN-γ and IL-17 [111]. PA-induction of SLAMF3 required the activation of STAT5 and PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, in keeping with previous data showing the key role of this pathway in PA-induced Th1/Th17 cell commitment [134]. The elevated SFA levels in obesity and T2DM might contribute to the abnormal T lymphocyte activation and increased Th1/Th17 responses observed in these conditions. It is worth noting that Th17 cell-mediated responses have been found to promote colorectal tumour initiation and growth in preclinical models and are associated with worse outcomes in CRC patients [135].

Chronic inflammation in obesity and metabolic diseases also results from mitochondrial dysfunction and redox imbalance, and SFA have been postulated to control these mechanisms. Stimulation of PBMC from healthy lean donors with PA, but not OA, results in decreased expression of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT), a key mitochondrial regulator of energy transduction and redox homeostasis, with a parallel increase of ROS and Th17 type cytokines [110]. NNT, whose expression is downregulated in obesity, was proposed as SFA-regulated rheostat of the redox balance that shapes T cell responses in obesity [110].

Conversely, POA was found to reduce ConA-induced T lymphocyte proliferation and to impair CD28 externalization, thus preventing the activation of transcription factors involved in inflammatory cytokine gene expression [113]. In the same study, treatment with OA results in reduced IFN-γ release and increased expression of anti-inflammatory factors [113]. POA and OA were also shown with Treg cell differentiation, whereas stimulation of circulating Treg cells with serum albumin-bound OA results in their increased survival, suggesting a role for these MUFA in maintaining immune homeostasis [113,114].

According to the effects on T lymphocyte proliferation reported in in vivo studies, EPA and DHA exposure of PBMC prior to PMA/ionomycin-induced activation was reported to reduce IL-2 and TNFα but not IFN-γ production by CD4+ T lymphocytes, through the activation of PPAR-γ [131].

These studies widely demonstrate the capacity of FA to finely regulate and orient immune responses and suggest that selective T cell-mediated responses can be elicited through either a direct effect of FA on lymphocytes or indirect modulation of the functions of antigen presenting cells, such as a monocyte and DC.

5. Conclusions

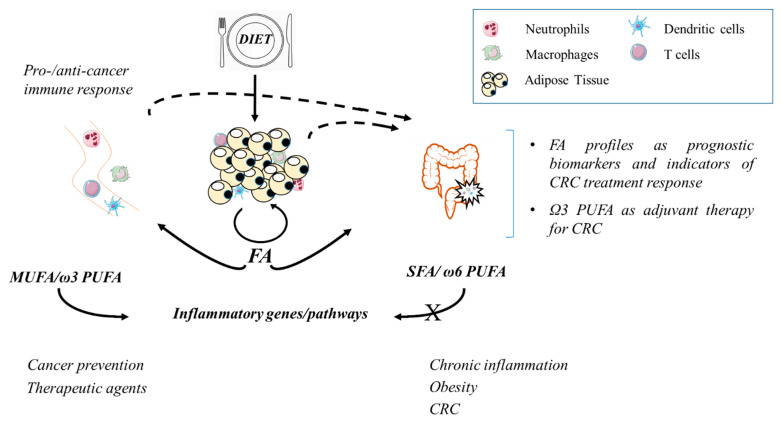

AT-associated inflammation promoted by unhealthy dietary habits and obesity is a main mechanism that may favour CRC development and progression [136]. Inflamed AT may contribute to tumorigenesis by releasing proinflammatory mediators, including FA, and by modifying the lipid metabolism, which is part of the reprogrammed energy metabolism that characterizes cancer [137]. In turn, cancer cells have the ability to perpetuate inflammation by inducing metabolic changes in AT and to use released FA as substrates for their proliferation [39,138]. Excessive free FA or unbalanced FA profiles characterizing obesity and CRC may also affect cancer development or progression by deeply regulating gene expression in immune cell populations active in cancer surveillance (Figure 2). This is particularly relevant for CRC and other gastrointestinal cancers whose onset and evolution are profoundly influenced by the immune system.

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of dietary fatty acid (FA)-mediated regulation of adipose tissue-associated and blood immune cells. The opposite regulation of inflammatory pathways by different FA classes and the consequences on the promotion or prevention of CRC and other obesity-related morbidities are depicted.

Genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, cyclooxygenases, and matrix metalloproteinases, or regulating ROS production are major targets of FA. The pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of different FA are exerted through the triggering of membrane receptors (TLR and GPR) and the regulation of different TF, and often involve the inhibition or activation of NF-kB and PPAR family members.

Chronic activation of proinflammatory and pro-oxidant signalling pathways in innate immunity cells and the promotion of Th17 type responses, induced by SFA and ω6 PUFA, can generate, at local and systemic levels, a suppressive microenvironment favouring immune evasion and cancer growth. On the other hand, dietary intake and/or supplementation of anti-inflammatory ω3 PUFA has the potential to foster a healthy immune system for cancer control and to lower the risk of developing CRC and other inflammation-related diseases. This can have profound implications for CRC prevention, and highlights the relevance of correct dietary habits and the pivotal role of AT in the health status preservation.

Beyond the regulatory effects on the immune response, anti-inflammatory FA might play a role in CRC as preventive or therapeutic agents by targeting several genes and signalling pathways in cancer cells, and by inducing epigenetic modifications [139]. They can also influence post-diagnosis CRC outcomes by exerting beneficial effects on efficacy and tolerability of chemotherapy [140]. Finally, evidence is emerging that FA profiles have the potential to discriminate between early and late CRC stages, suggesting that they might be studied as possible prognostic biomarkers and indicators of treatment response [139,141]. However, available clinical data are still insufficient and definitive prospective randomized control trials are needed in the near future to clearly demonstrate the preventive and prognostic role of FA in CRC.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to S. Gessani for critically reading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

M.D.C. and L.C. made substantial contributions to conception, design, and writing of the review; R.V., B.S. and B.V. contributed to the literature search, writing, and editing of the manuscript; R.M. made substantial contribution to the discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Collaboration N.C.D.R.F. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: A pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James W.P.T., McPherson K. The costs of overweight. Lancet. Public Health. 2017;2:e203–e204. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik V.S., Willett W.C., Hu F.B. Global obesity: Trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013;9:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cozzo A.J., Fuller A.M., Makowski L. Contribution of adipose tissue to development of cancer. Compr. Physiol. 2017;8:237–282. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thanikachalam K., Khan G. Colorectal cancer and nutrition. Nutrients. 2019;11:164. doi: 10.3390/nu11010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keum N., Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;16:713–732. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardou M., Barkun A.N., Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62:933–947. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J., Morley T.S., Kim M., Clegg D.J., Scherer P.E. Obesity and cancer--mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014;10:455–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Useros J., Garcia-Foncillas J. Obesity and colorectal cancer: Molecular features of adipose tissue. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0772-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alwarawrah Y., Kiernan K., MacIver N.J. Changes in nutritional status impact immune cell metabolism and function. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1055. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matafome P., Seica R. Function and dysfunction of adipose tissue. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017;19:3–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63260-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh J.Y., Park Y.J., Ham M., Kim J.B. Crosstalk between adipocytes and immune cells in adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in obesity. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:365–371. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kershaw E.E., Flier J.S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:2548–2556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meiliana A., Dewi N.M., Wijaya A. Adipose tissue, inlammation (meta-inlammation) and obesity management. Indones Biomed. J. 2015;7:129–146. doi: 10.18585/inabj.v7i3.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y.C., Lee S.E., Jin Y., Park H.W., Chun K.H., Lee H.W. Classifying the linkage between adipose tissue inflammation and tumor growth through cancer-associated adipocytes. Mol. Cells. 2020;43:763–773. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2020.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masoodi M., Kuda O., Rossmeisl M., Flachs P., Kopecky J. Lipid signaling in adipose tissue: Connecting inflammation & metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1851:503–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocha D.M., Bressan J., Hermsdorff H.H. The role of dietary fatty acid intake in inflammatory gene expression: A critical review. Sao Paulo Med. J. Rev. Paul. Med. 2017;135:157–168. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2016.008607072016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calder P.C. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: From molecules to man. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017;45:1105–1115. doi: 10.1042/BST20160474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Beek C.M., Dejong C.H.C., Troost F.J., Masclee A.A.M., Lenaerts K. Role of short-chain fatty acids in colonic inflammation, carcinogenesis, and mucosal protection and healing. Nutr. Rev. 2017;75:286–305. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calder P.C., Yaqoob P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and human health outcomes. BioFactors. 2009;35:266–272. doi: 10.1002/biof.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ralston J.C., Lyons C.L., Kennedy E.B., Kirwan A.M., Roche H.M. Fatty Acids and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation in metabolic tissues. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017;37:77–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wajchenberg B.L. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: Their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2000;21:697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo M., Zatterale F., Naderi J., Parrillo L., Formisano P., Raciti G.A., Beguinot F., Miele C. Adipose tissue dysfunction as determinant of obesity-associated metabolic complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2358. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaittinen M., Mannisto V., Kakela P., Agren J., Tiainen M., Schwab U., Pihlajamaki J. Interorgan cross talk between fatty acid metabolism, tissue inflammation, and FADS2 genotype in humans with obesity. Obesity. 2017;25:545–552. doi: 10.1002/oby.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garaulet M., Perez-Llamas F., Perez-Ayala M., Martinez P., de Medina F.S., Tebar F.J., Zamora S. Site-specific differences in the fatty acid composition of abdominal adipose tissue in an obese population from a Mediterranean area: Relation with dietary fatty acids, plasma lipid profile, serum insulin, and central obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001;74:585–591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Archivio M., Scazzocchio B., Giammarioli S., Fiani M.L., Vari R., Santangelo C., Veneziani A., Iacovelli A., Giovannini C., Gessani S., et al. omega3-PUFAs exert anti-inflammatory activity in visceral adipocytes from colorectal cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Corno M., D’Archivio M., Conti L., Scazzocchio B., Vari R., Donninelli G., Varano B., Giammarioli S., De Meo S., Silecchia G., et al. Visceral fat adipocytes from obese and colorectal cancer subjects exhibit distinct secretory and omega6 polyunsaturated fatty acid profiles and deliver immunosuppressive signals to innate immunity cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:63093–63105. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong J., Campos H., McGarvey S., Wu Z., Goldberg R., Baylin A. Genetic variation in stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 is associated with metabolic syndrome prevalence in Costa Rican adults. J. Nutr. 2011;141:2211–2218. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.143503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scazzocchio B., Vari R., Silenzi A., Giammarioli S., Masotti A., Baldassarre A., Santangelo C., D’Archivio M., Giovannini C., Del Corno M., et al. Dietary habits affect fatty acid composition of visceral adipose tissue in subjects with colorectal cancer or obesity. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020;59:1463–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boden G. Obesity and free fatty acids. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2008;37:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arner P., Ryden M. Fatty acids, obesity and insulin resistance. Obes. Facts. 2015;8:147–155. doi: 10.1159/000381224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodson L., McQuaid S.E., Karpe F., Frayn K.N., Fielding B.A. Differences in partitioning of meal fatty acids into blood lipid fractions: A comparison of linoleate, oleate, and palmitate. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;296:E64–E71. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90730.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iggman D., Arnlov J., Cederholm T., Riserus U. Association of adipose tissue fatty acids with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in elderly men. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:745–753. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye Z., Cao C., Li Q., Xu Y.J., Liu Y. Different dietary lipid consumption affects the serum lipid profiles, colonic short chain fatty acid composition and the gut health of Sprague Dawley rats. Food Res. Int. 2020;132:109117. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Dijk S.J., Feskens E.J., Bos M.B., Hoelen D.W., Heijligenberg R., Bromhaar M.G., de Groot L.C., de Vries J.H., Muller M., Afman L.A. A saturated fatty acid-rich diet induces an obesity-linked proinflammatory gene expression profile in adipose tissue of subjects at risk of metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90:1656–1664. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May-Wilson S., Sud A., Law P.J., Palin K., Tuupanen S., Gylfe A., Hanninen U.A., Cajuso T., Tanskanen T., Kondelin J., et al. Pro-inflammatory fatty acid profile and colorectal cancer risk: A Mendelian randomisation analysis. Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;84:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carroll R.G., Zaslona Z., Galvan-Pena S., Koppe E.L., Sevin D.C., Angiari S., Triantafilou M., Triantafilou K., Modis L.K., O’Neill L.A. An unexpected link between fatty acid synthase and cholesterol synthesis in proinflammatory macrophage activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:5509–5521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pakiet A., Kobiela J., Stepnowski P., Sledzinski T., Mika A. Changes in lipids composition and metabolism in colorectal cancer: A review. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18:29. doi: 10.1186/s12944-019-0977-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen Y.A., Xing X., Harris J.W., Zaytseva Y.Y., Mitov M.I., Napier D.L., Weiss H.L., Mark Evers B., Gao T. Adipocytes activate mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and autophagy to promote tumor growth in colon cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2593. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okuno M., Hamazaki K., Ogura T., Kitade H., Matsuura T., Yoshida R., Hijikawa T., Kwon M., Arita S., Itomura M., et al. Abnormalities in fatty acids in plasma, erythrocytes and adipose tissue in Japanese patients with colorectal cancer. In Vivo. 2013;27:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giuliani A., Ferrara F., Scimo M., Angelico F., Olivieri L., Basso L. Adipose tissue fatty acid composition and colon cancer: A case-control study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014;53:1029–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cottet V., Vaysse C., Scherrer M.L., Ortega-Deballon P., Lakkis Z., Delhorme J.B., Deguelte-Lardiere S., Combe N., Bonithon-Kopp C. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and colorectal cancer: A case-control study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;101:192–201. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry E.M., Zimmerman J., Peser M., Ligumsky M. Dietary fat, adipose tissue composition, and the development of carcinoma of the colon. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1986;77:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neoptolemos J.P., Clayton H., Heagerty A.M., Nicholson M.J., Johnson B., Mason J., Manson K., James R.F., Bell P.R. Dietary fat in relation to fatty acid composition of red cells and adipose tissue in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1988;58:575–579. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mosconi E., Minicozzi A., Marzola P., Cordiano C., Sbarbati A. (1) H-MR spectroscopy characterization of the adipose tissue associated with colorectal tumor. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI. 2014;39:469–474. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bakker N., Van’t Veer P., Zock P.L. Adipose fatty acids and cancers of the breast, prostate and colon: An ecological study. EURAMIC Study Group. Int. J. Cancer. 1997;72:587–591. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<587::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L., Han L., He J., Lv J., Pan R., Lv T. A high serum-free fatty acid level is associated with cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020;146:705–710. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aglago E.K., Huybrechts I., Murphy N., Casagrande C., Nicolas G., Pischon T., Fedirko V., Severi G., Boutron-Ruault M.C., Fournier A., et al. Consumption of fish and long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in a Large European Cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2020;18:654–666.e656. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suganami T., Tanimoto-Koyama K., Nishida J., Itoh M., Yuan X., Mizuarai S., Kotani H., Yamaoka S., Miyake K., Aoe S., et al. Role of the Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB pathway in saturated fatty acid-induced inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251608.09329.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guzik T.J., Skiba D.S., Touyz R.M., Harrison D.G. The role of infiltrating immune cells in dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017;113:1009–1023. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Del Corno M., Conti L., Gessani S. Innate lymphocytes in adipose tissue homeostasis and their alterations in obesity and colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2556. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castellano-Castillo D., Morcillo S., Clemente-Postigo M., Crujeiras A.B., Fernandez-Garcia J.C., Torres E., Tinahones F.J., Macias-Gonzalez M. Adipose tissue inflammation and VDR expression and methylation in colorectal cancer. Clin. Epigenetics. 2018;10:60. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffin C., Eter L., Lanzetta N., Abrishami S., Varghese M., McKernan K., Muir L., Lane J., Lumeng C.N., Singer K. TLR4, TRIF, and MyD88 are essential for myelopoiesis and CD11c(+) adipose tissue macrophage production in obese mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:8775–8786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luna-Vital D., Luzardo-Ocampo I., Cuellar-Nunez M.L., Loarca-Pina G., Gonzalez de Mejia E. Maize extract rich in ferulic acid and anthocyanins prevents high-fat-induced obesity in mice by modulating SIRT1, AMPK and IL-6 associated metabolic and inflammatory pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020;79:108343. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2020.108343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boughanem H., Cabrera-Mulero A., Hernandez-Alonso P., Bandera-Merchan B., Tinahones A., Tinahones F.J., Morcillo S., Macias-Gonzalez M. The expression/methylation profile of adipogenic and inflammatory transcription factors in adipose tissue are linked to obesity-related colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:1629. doi: 10.3390/cancers11111629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bennacer A.F., Haffaf E., Kacimi G., Oudjit B., Koceir E.A. Association of polyunsaturated/saturated fatty acids to metabolic syndrome cardiovascular risk factors and lipoprotein (a) in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients. Ann. Biol. Clin. 2017;75:293–304. doi: 10.1684/abc.2017.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serhan C.N., Yacoubian S., Yang R. Anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:279–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neacsu O., Cleveland K., Xu H., Tchkonia T.T., Kirkland J.L., Boney C.M. IGF-I attenuates FFA-induced activation of JNK1 phosphorylation and TNFalpha expression in human subcutaneous preadipocytes. Obesity. 2013;21:1843–1849. doi: 10.1002/oby.20329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Youssef-Elabd E.M., McGee K.C., Tripathi G., Aldaghri N., Abdalla M.S., Sharada H.M., Ashour E., Amin A.I., Ceriello A., O’Hare J.P., et al. Acute and chronic saturated fatty acid treatment as a key instigator of the TLR-mediated inflammatory response in human adipose tissue, in vitro. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murumalla R.K., Gunasekaran M.K., Padhan J.K., Bencharif K., Gence L., Festy F., Cesari M., Roche R., Hoareau L. Fatty acids do not pay the toll: Effect of SFA and PUFA on human adipose tissue and mature adipocytes inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:175. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferguson J.F., Roberts-Lee K., Borcea C., Smith H.M., Midgette Y., Shah R. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuate inflammatory activation and alter differentiation in human adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019;64:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee K.R., Midgette Y., Shah R. Fish Oil Derived Omega 3 Fatty Acids Suppress Adipose NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling in Human Obesity. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019;3:504–515. doi: 10.1210/js.2018-00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donninelli G., Del Corno M., Pierdominici M., Scazzocchio B., Vari R., Varano B., Pacella I., Piconese S., Barnaba V., D’Archivio M., et al. Distinct blood and visceral adipose tissue regulatory t cell and innate lymphocyte profiles characterize obesity and colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:643. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Del Corno M., Baldassarre A., Calura E., Conti L., Martini P., Romualdi C., Vari R., Scazzocchio B., D’Archivio M., Masotti A., et al. Transcriptome profiles of human visceral adipocytes in obesity and colorectal cancer unravel the effects of body mass index and polyunsaturated fatty acids on genes and biological processes related to tumorigenesis. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:265. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ralston J.C., Matravadia S., Gaudio N., Holloway G.P., Mutch D.M. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of adipocyte FADS1 and FADS2 expression and function. Obesity. 2015;23:725–728. doi: 10.1002/oby.21035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao H., Geng T., Huang T., Zhao Q. Fish oil supplementation and insulin sensitivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Souza D.R., Pieri B., Comim V.H., Marques S.O., Luciano T.F., Rodrigues M.S., De Souza C.T. Fish oil reduces subclinical inflammation, insulin resistance, and atherogenic factors in overweight/obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A pre-post pilot study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2020;34:107553. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Mello V.D., Dahlman I., Lankinen M., Kurl S., Pitkanen L., Laaksonen D.E., Schwab U.S., Erkkila A.T. The effect of different sources of fish and camelina sativa oil on immune cell and adipose tissue mRNA expression in subjects with abnormal fasting glucose metabolism: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Diabetes. 2019;9:1. doi: 10.1038/s41387-018-0069-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shah R.D., Xue C., Zhang H., Tuteja S., Li M., Reilly M.P., Ferguson J.F. Expression of Calgranulin Genes S100A8, S100A9 and S100A12 Is Modulated by n-3 PUFA during inflammation in adipose tissue and mononuclear cells. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0169614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huerta A.E., Prieto-Hontoria P.L., Fernandez-Galilea M., Escote X., Martinez J.A., Moreno-Aliaga M.J. Effects of dietary supplementation with EPA and/or alpha-lipoic acid on adipose tissue transcriptomic profile of healthy overweight/obese women following a hypocaloric diet. BioFactors. 2017;43:117–131. doi: 10.1002/biof.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holt P.R., Aleman J.O., Walker J.M., Jiang C.S., Liang Y., de Rosa J.C., Giri D.D., Iyengar N.M., Milne G.L., Hudis C.A., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation is not anti-inflammatory in adipose tissue of healthy obese postmenopausal women. Int. J. Nutr. 2017;1:31–49. doi: 10.14302/issn.2379-7835.ijn-17-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klingel S.L., Valsesia A., Astrup A., Kunesova M., Saris W.H.M., Langin D., Viguerie N., Mutch D.M. FADS1 genotype is distinguished by human subcutaneous adipose tissue fatty acids, but not inflammatory gene expression. Int. J. Obes. 2019;43:1539–1548. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0169-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yessoufou A., Ple A., Moutairou K., Hichami A., Khan N.A. Docosahexaenoic acid reduces suppressive and migratory functions of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:2377–2388. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900101-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim W., Khan N.A., McMurray D.N., Prior I.A., Wang N., Chapkin R.S. Regulatory activity of polyunsaturated fatty acids in T-cell signaling. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou H., Urso C.J., Jadeja V. Saturated fatty acids in obesity-associated inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020;13:1–14. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S229691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Radzikowska U., Rinaldi A.O., Celebi Sozener Z., Karaguzel D., Wojcik M., Cypryk K., Akdis M., Akdis C.A., Sokolowska M. The influence of dietary fatty acids on immune responses. Nutrients. 2019;11:2990. doi: 10.3390/nu11122990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ulven S.M., Holven K.B., Rundblad A., Myhrstad M.C.W., Leder L., Dahlman I., Mello V.D., Schwab U., Carlberg C., Pihlajamaki J., et al. An Isocaloric Nordic Diet Modulates RELA and TNFRSF1A Gene Expression in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome-A SYSDIET Sub-Study. Nutrients. 2019;11:2932. doi: 10.3390/nu11122932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouwens M., Afman L.A., Muller M. Fasting induces changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles related to increases in fatty acid beta-oxidation: Functional role of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;86:1515–1523. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O’Grada C.M., Morine M.J., Morris C., Ryan M., Dillon E.T., Walsh M., Gibney E.R., Brennan L., Gibney M.J., Roche H.M. PBMCs reflect the immune component of the WAT transcriptome--implications as biomarkers of metabolic health in the postprandial state. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014;58:808–820. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ulven S.M., Christensen J.J., Nygard O., Svardal A., Leder L., Ottestad I., Lysne V., Laupsa-Borge J., Ueland P.M., Midttun O., et al. Using metabolic profiling and gene expression analyses to explore molecular effects of replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat-a randomized controlled dietary intervention study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019;109:1239–1250. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rundblad A., Larsen S.V., Myhrstad M.C., Ottestad I., Thoresen M., Holven K.B., Ulven S.M. Differences in peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression and triglyceride composition in lipoprotein subclasses in plasma triglyceride responders and non-responders to omega-3 supplementation. Genes Nutr. 2019;14:10. doi: 10.1186/s12263-019-0633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rudkowska I., Paradis A.M., Thifault E., Julien P., Tchernof A., Couture P., Lemieux S., Barbier O., Vohl M.C. Transcriptomic and metabolomic signatures of an n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in a normolipidemic/normocholesterolemic Caucasian population. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013;24:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rudkowska I., Ponton A., Jacques H., Lavigne C., Holub B.J., Marette A., Vohl M.C. Effects of a supplementation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with or without fish gelatin on gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in obese, insulin-resistant subjects. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2011;4:192–202. doi: 10.1159/000330226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polus A., Zapala B., Razny U., Gielicz A., Kiec-Wilk B., Malczewska-Malec M., Sanak M., Childs C.E., Calder P.C., Dembinska-Kiec A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation influences the whole blood transcriptome in women with obesity, associated with pro-resolving lipid mediator production. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1861:1746–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vedin I., Cederholm T., Freund-Levi Y., Basun H., Garlind A., Irving G.F., Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M., Wahlund L.O., Dahlman I., Palmblad J. Effects of DHA-rich n-3 fatty acid supplementation on gene expression in blood mononuclear leukocytes: The OmegAD study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bouwens M., van de Rest O., Dellschaft N., Bromhaar M.G., de Groot L.C., Geleijnse J.M., Muller M., Afman L.A. Fish-oil supplementation induces antiinflammatory gene expression profiles in human blood mononuclear cells. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90:415–424. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rahmani E., Jamilian M., Dadpour B., Nezami Z., Vahedpoor Z., Mahmoodi S., Aghadavod E., Taghizadeh M., Beiki Hassan A., Asemi Z. The effects of fish oil on gene expression in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018;48 doi: 10.1111/eci.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Skulas-Ray A.C., Kris-Etherton P.M., Harris W.S., Vanden Heuvel J.P., Wagner P.R., West S.G. Dose-response effects of omega-3 fatty acids on triglycerides, inflammation, and endothelial function in healthy persons with moderate hypertriglyceridemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;93:243–252. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Myhrstad M.C., Ulven S.M., Gunther C.C., Ottestad I., Holden M., Ryeng E., Borge G.I., Kohler A., Bronner K.W., Thoresen M., et al. Fish oil supplementation induces expression of genes related to cell cycle, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells: A transcriptomic approach. J. Intern. Med. 2014;276:498–511. doi: 10.1111/joim.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rundblad A., Holven K.B., Bruheim I., Myhrstad M.C., Ulven S.M. Effects of fish and krill oil on gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and circulating markers of inflammation: A randomised controlled trial. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018;7:e10. doi: 10.1017/jns.2018.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]