Abstract

Antibiotic biosynthesis by microorganisms is commonly regulated through autoinduction, which allows producers to quickly amplify the production of antibiotics in response to environmental cues. Antibiotic autoinduction generally involves one pathway-specific transcriptional regulator that perceives an antibiotic as a signal and then directly stimulates transcription of the antibiotic biosynthesis genes. Pyoluteorin is an autoregulated antibiotic produced by some Pseudomonas spp. including the soil bacterium Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. In this study, we show that PltR, a known pathway-specific transcriptional activator of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes, is necessary but not sufficient for pyoluteorin autoinduction in Pf-5. We found that pyoluteorin is perceived as an inducer by PltZ, a second pathway-specific transcriptional regulator that directly represses the expression of genes encoding a transporter in the pyoluteorin gene cluster. Mutation of pltZ abolished the autoinducing effect of pyoluteorin on the transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes. Overall, our results support an alternative mechanism of antibiotic autoinduction by which the two pathway-specific transcriptional regulators PltR and PltZ coordinate the autoinduction of pyoluteorin in Pf-5. Possible mechanisms by which PltR and PltZ mediate the autoinduction of pyoluteorin are discussed.

Keywords: autoinduction, pyoluteorin, transporter, regulation, Pseudomonas protegens

1. Introduction

Autoinduction, also called positive feedback regulation, is commonly used by bacteria to induce phenotypes required to respond promptly to a particular environmental condition [1,2,3]. The best-documented mechanism is the autoinduction of N-acyl-homoserine lactones, also known as quorum sensing signal molecules, which regulate cell-to-cell communication in many bacteria. In a classic model, N-acyl-homoserine lactone binds to its cognate response regulator and directly activates expression of N-acyl-homoserine lactone biosynthesis gene(s), which leads to an enhanced level of the signal molecule [4].

In addition to the quorum sensing signal molecules, production of many antibiotics is also controlled by autoinduction [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Through autoregulation, antibiotics can accumulate rapidly, allowing producers to respond promptly to competition with other microorganisms or predators [7]. Some antibiotics, such as 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol [16] and jadomycins [14], bind to their cognate response regulators and directly induce expression of antibiotic biosynthesis genes, a mechanism similar to the autoinduction of quorum sensing signal molecules. For the vast majority of antibiotics, however, mechanisms of autoinduction are unknown.

This study focuses on the autoinduction of pyoluteorin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic produced by certain strains of Pseudomonas species including P. aeruginosa [17] and P. protegens (previously known as P. fluorescens) [18]. Autoinduction of pyoluteorin was first demonstrated in P. protegens Pf-5. Adding nanomolar concentrations of pyoluteorin to Pf-5′s cultures enhanced pyoluteorin production and transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes [9]. Later, pyoluteorin autoinduction was also observed in P. protegens CHA0 [19] and P. aeruginosa M18 [20]. Production of pyoluteorin requires a pathway-specific response regulator PltR (Figure 1) [21], which binds to the promoter region of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes and activates their transcription [22]. PltR belongs to the LysR family regulators, which generally require activators for their activities [23]. Pyoluteorin was proposed to bind directly to PltR, thereby promoting PltR-mediated transcriptional activation of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes and mediating autoinduction [22]. However, 2,4-dichlorobenzene-1,3,5-triol, a chlorinated phloroglucinol (PG-Cl2) with a chemical structure distinct from pyoluteorin (Figure 1A), is now known to be required for PltR-mediated activation of pyoluteorin production and its biosynthesis genes [24]. Mechanisms of pyoluteorin autoinduction remain unknown. Here we report that PltR is required but not sufficient for pyoluteorin autoinduction, and that PltZ, a second transcriptional regulator encoded in the plt gene cluster (Figure 1A), binds directly to pyoluteorin as an inducer and is also required for pyoluteorin autoinduction.

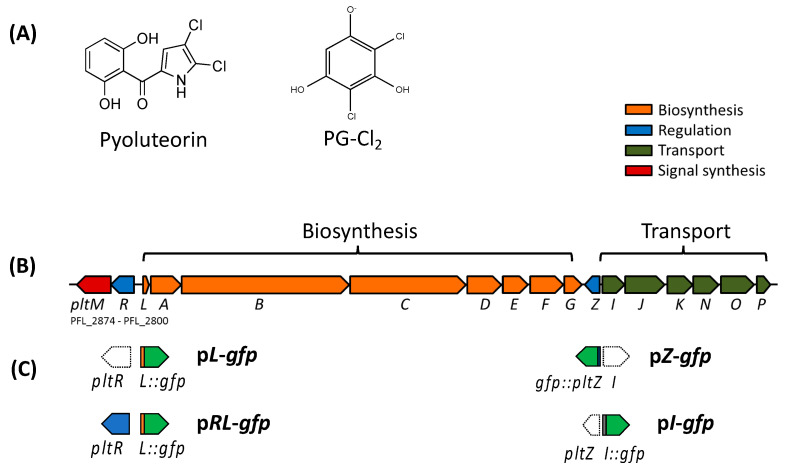

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of pyoluteorin and PG-Cl2 (2,4-dichlorobenzene-1,3,5-triol) (A), pyoluteorin biosynthesis gene (plt) cluster of Pf-5 (B), and promoter:: gfp fusions of the transcriptional reporter constructs used in this work (C). Figures are modified from previous publication [24]. The plt gene cluster contains two transcriptional regulatory genes pltR and pltZ. PG-Cl2, an activator of PltR, is synthesized by PltM with phloroglucinol (PG) as a substrate. Open arrows in (C) indicate the genes are not included in the related constructs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Cultural Conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 and its mutants were cultured at 27 °C on King’s Medium B agar [25], Nutrient Agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 1% glycerol (NAGly) or Nutrient Broth (Becton, Dickenson, and Company) supplemented with 1% glycerol (NBGly). Liquid cultures were grown with shaking at 200 r.p.m.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmid, and primers used in this study.

| Strains, Plasmids, or Primers | Genotype, Relevant Characteristics or Sequences | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains # | ||

| P. protegens | ||

| LK099 | Wild-type strain Pf-5. | [26] |

| JL4805 | Pf-5 derivative strain contains an in-frame deletion of pltA in the chromosome. | [27] |

| LK530 | Pf-5 derivative strain contains an in-frame deletion of pltA and pltR in the chromosome. This mutant was generated by deleting pltR in JL4805. | This study |

| LK419 | Pf-5 derivative strain contains an in-frame deletion of pltA and pltZ in the chromosome. This mutant was generated by deleting pltZ in JL4805. | This study |

| P. fluorescens SBW25 | SBW25 is a member of the P. fluorescens group that does not contain plt gene cluster. | [28] |

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1 | recA pro hsdR−M+ RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 Smr Tpr | [29] |

| BL21 (DE3) | ompT hsdSB (rB−mB−) gal dcm | NEB |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Tc | Gene replacement vector with MCS from pUC18, sacB+ Tcr | [30] |

| pEX18Tc-ΔpltR | pEX18Tc containing pltR with a 925-bp in-frame deletion. | [24] |

| pEX18Tc-ΔpltZ | pEX18Tc containing pltZ with a 621-bp in-frame deletion. | This study |

| pPROBE-NT | pBBR1, containing a promoterless gfp, Kmr | [31] |

| pL-gfp | Called ppltL-gfp previously. Contains the intergenic region between pltR and pltL including pltL promoter fused with a promoterless gfp. | [32] |

| pRL-gfp | Contains pltR and the intergenic region between pltR and pltL including pltL promoter fused with a promoterless gfp. | [24] |

| pI-gfp | Contains the intergenic region between pltI and pltZ including pltI promoter fused with a promoterless gfp. | This study |

| pZ-gfp | Contains the intergenic region between pltI and pltZ including pltZ promoter fused with a promoterless gfp. | This study |

| pME6010 | pACYC177-pVS1 shuttle vector, Tcr | [33] |

| PME6010-pltZ | pME6010 with a 697-bp XhoI-KpnI PCR fragment amplified from the genomic DNA of Pf-5, containing a constitutively expressed pltZ gene. | This study |

| Primers * | oligonucleotide sequences (5′to 3′) | |

| pltZ-F2 | ACTCGAGAAAATAACAGATACTGGCCATG | |

| pltZ-R2 | ATAGGTACCGACTATTGGGCAATGGC | |

| pltI-F1 | ATAGGATCCAGCAGACGGAATTTGGGC | |

| pltI-R1 | TATGGTACCCCTACAATCAACTGCTTCTTC | |

| pltI-F4 | TGGCGAATGTCGACGTTGC | |

| pltI-R4 | TATGAATTCCTCGTGGTCTGAGCGG | |

| pltZ 5′primer | GTCATACATATGAAGCAACCCCCCGCTC | |

| pltZ 3′primer | ATGATCTCGAGCCGACTATTGGGCAATG | |

| pltZ UpF-Xba | CTCCTCTCTAGATCAAAACGTGCCTTGGACTG | |

| pltZ UpR | ACTATTGGGCAATGATGTTCCTCGTGGTCTGAG | |

| pltZ DnF | ACGAGGAACATCATTGCCCAATAGTCGGCTCA | |

| pltZ DnR-Xba | CACACCTCTAGAACATCCCCTGCTGTTTCTTC |

# abbreviations of antibiotics and their concentrations used in this work are: Tc, tetracycline (10 μg/mL for E. coli, 200 μg/mL for Pf-5); Km, kanamycin (50 μg/mL). * underlines show DNA restriction enzyme sites that were used for cloning. All primers were designed in this study.

2.2. Construction of GFP Transcriptional Reporters and Expression Constructs

To measure the promoter activity of pltZ, a 235-bp DNA fragment containing pltZ promoter was amplified from the Pf-5 genome using oligonucleotide pair pltI-F4/pltI-R4 (Table 1), digested with EcoRI and SalI, and ligated into pPROBE-NT to generate reporter construct pZ-gfp which contains the pltZpromoter:gfp transcriptional fusion. Similarly, a 574-bp DNA fragment containing pltI promoter was amplified using oligonucleotide pair pltI-F1/pltI-R1 (Table 1), digested with BamHI and KpnI, and ligated into pPROBE-NT to generate reporter construct pI-gfp which contains the pltIpromoter: gfp transcriptional fusion.

The expression construct pME6010-pltZ was made by inserting a 697-bp XhoI-KpnI PCR fragment containing the entire pltZ gene and a 21-bp 5′ untranslated region of pltZ, into pME6010 digested by the same restriction enzymes. This DNA fragment was amplified from the genomic DNA of Pf-5 using oligonucleotide pair pltZ-F2/pltZ-R2 (Table 1). The expression of pltZ gene was placed under the control of a constitutive kanamycin-resistance promoter (Pk) carried by the vector pME6010 [33].

The expression construct pET28a-pltZ was made by inserting a 692-bp XhoI-NdeI PCR fragment containing pltZ gene into pET28a digested by the same restriction enzymes. This DNA fragment was amplified from the genomic DNA of Pf-5 using oligonucleotide pair pltZ 5′/pltZ 3′ (Table 1). Purified PltZ protein from the generated expression construct contains a 6xHis tag at the N-terminus. All these constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis.

2.3. Construction of Pf-5 Mutants

The ΔpltAΔpltR double mutant was made by deleting pltR from the chromosome of a ΔpltA mutant which was made previously [27]. To delete pltR gene from the chromosome of Pf-5, a pltR deletion construct P18Tc-ΔpltR, which was made previously [24], was transferred by conjugation from E. coli S17-1 to Pf-5 to delete 925-bp inside of the pltR gene in the chromosome of Pf-5. The deletion was confirmed by PCR analysis.

Similarly, the ΔpltAΔpltZ double mutant was made by deleting pltZ from the chromosome of the ΔpltA mutant. To delete the pltZ, two DNA fragments flanking the pltZ gene were PCR amplified using the oligonucleotide pair pltZ UpF-Xba/pltZ UpR and pltZ DnR-Xba/pltZ DnF (Table 1). These two fragments were fused together by PCR and digested using XbaI to generate a 1003-bp DNA fragment containing pltZ with a 621-bp internal deletion. This DNA fragment was ligated to pEX18Tc to create construct p18Tc-ΔpltZ. This deletion construct was introduced into the ΔpltA mutant to make the ΔpltAΔpltZ double mutant.

2.4. Assays for Monitoring GFP Activity of Reporter Constructs

The GFP-based transcriptional reporter assays were modified from a previous report [32]. Briefly, Pf-5 strains containing reporter constructs were cultured overnight in NBGly plus kanamycin (50 μg/mL) at 27 °C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. The cells were washed once into 1 mL fresh NBGly plus kanamycin with an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0, and then used to inoculate 200 μL NBGly plus kanamycin to obtain a start OD600 of 0.01. Each strain was grown in three wells of a 96-well plate, which was incubated in a microplate shaker at 27 °C with shaking at approximately 400 r.p.m. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the OD600. The green fluorescence of bacteria was monitored by measuring emission at 535nm with an excitation at 485nm and corrected for background by subtracting fluorescence emitted by control strain which has an empty vector of the reporter construct.

2.5. Protein Purification and In Vitro Activity Assays

Protein overexpression and purification of PltZ was modified from previous method [24]. Briefly, the construct pET28a-pltZ was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). Cells were cultured in LB broth with 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.5, then induced by 0.4 mM IPTG, and incubated overnight at 20 °C. The cells were lysed in Tris-NaCl buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl). The PltZ proteins with a N-terminal 6xHis tag were purified using a Ni-NTA Purification System (Invitrogen) and dialyzed in Tris-NaCl buffer. The protein concentrations were determined using a DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) experiments were performed at 25 °C using a LightShift™ Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (ThermoFisher). A 44-bp DNA probe named pltIZ (TATTTTCTAATTTAAATTCAAATTGAATTTTAATTAGGCCTTGG) and a 66-bp DNA probe named pltRL (TCGGGGCTGTTTTGCCTTTGCGGATATGCAAAGGCCTTTTGCAAAAACGGCTATTCACAAGTGCAT), that contain the putative promoter region of pltI and pltL, respectively, were synthesized and labeled with biotins using a Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (ThermoFisher). Labeled DNA probes (1 nM) were mixed with different concentrations of PltZ protein and incubated at 25 °C for 20 min in a 20 μL reaction. If needed, unlabeled DNA probes (1 μM) were used to compete with the labeled DNA in binding PltZ. Various concentrations of pyoluteorin were added in the reaction to test if this compound can release free DNA probes from the protein-DNA complex. The reaction samples were loaded to a 5% native PAGE gel (Mini-PROTEAN® TBE Gel, Bio-Rad) and electrophorized in 0.5× Tris Borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at 80 V for one hour in a 4 °C cold room. The DNA samples were transferred onto a nylon membrane (Zeta-Probe® Membrane, 9 × 12 cm, Bio-Rad) which then was exposed to a UV light treatment at 254nm for 10min to fix the nucleotides and the images were developed using X-ray films (CL-XPosure™ Film, ThermoFisher).

Interaction of PltZ with pyoluteorin was tested by two approaches. In the first approach, different concentrations (0–57.5 μM) of pyoluteorin were added into a PltZ protein solution (39 μM) which was prepared in a Tris-HCl buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.0). Absorbance of PltZ protein, pyoluteorin compound and their complex was measured in a 1-cm-path cuvette using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Beckman DU730). The protein-compound solution which contains PltZ protein over saturated with pyoluteorin compound (57.5 μM) was loaded onto a Sephadex G-25 column (1 × 20 cm) preequilibrated and washed with 80 mL of the Tris-HCl buffer. The PltZ-pyoluteorin complex was eluted with 7 mL of the Tris-HCl buffer. The absorbance of purified PltZ-pyoluteorin complex was measured using the same method described above.

In the second approach, Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed at 25 °C using a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter (Malvern, US). Pyoluteorin was dissolved in methanol first and then diluted in the Tris-HCl buffer to a concentration of 100 μM. The titration assay included an initial 2 μL injection, followed by 44 (10 μL) injections of pyoluteorin into PltZ protein solution prepared above, accompanied by stirring at a constant rate. Protein samples and compound solutions were degassed by centrifugation at 14,000 r.p.m. for 20 min prior to the titration experiment. Data were processed using Origin 7.0 and fit to an independent binding model to calculate the thermodynamic parameters of interactions between PltZ and pyoluteorin.

3. Results

3.1. PltR Is Required But Not Sufficient for the Autoinduction of Pyoluteorin

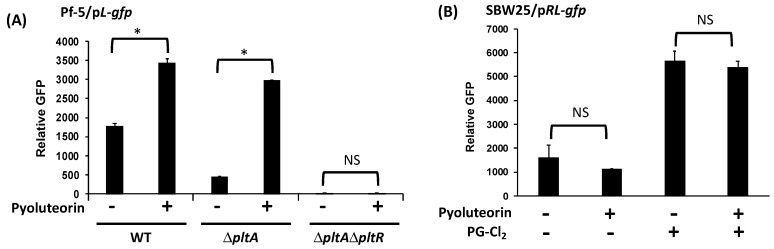

To investigate the autoinduction of pyoluteorin, purified pyoluteorin was added into cultures of Pf-5 strains. A ΔpltA mutant was used to exclude the influence of internal pyoluteorin on the expression of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes. The promoter activity of pltL, the first gene of the pyoluteorin biosynthesis gene cluster, was measured using the reporter construct pL-gfp which contains the pltL promoter fused with a promterless gfp (Figure 1B) [32]. Results show that amendment of pyoluteorin induced a significantly higher promoter activity of pltL in both the wild type Pf-5 and the ΔpltA mutant than in control cultures without pyoluteorin treatment (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Autoinduction of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes requires pltR. (A) pltL promoter activity was measured using the GFP reporter construct pL-gfp in wild type (WT) Pf-5 and its mutants. (B) pltL promoter activity was measured using the GFP reporter construct pRL-gfp in strain SBW25. The promoter activity was measured as relative GFP (fluorescence of GFP divided by OD600) recorded at 24 h (A) and 15 h (B) post inoculation (hpi). Pyoluteorin and PG-Cl2 were added to the cultures at a concentration of 1 μM and 10 nM, respectively. The inducing effect of PG-Cl2 on pltL promoter activity has been reported previously [24] and is confirmed in this study. * indicates treatments are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by the Student t-test. NS: not significant. Data are means and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates from a representative experiment repeated three times with similar results.

pltR encodes a transcriptional regulator known to activate the expression of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes in Pf-5 (Figure 1) [21]. Consistent with the previous report, mutation of pltR in the ΔpltA mutant background markedly reduced pltL promoter activity (Figure 2A). Adding pyoluteorin into the ΔpltAΔpltR mutant did not induce pltL promoter activity, indicating pltR is indispensable in pyoluteorin autoinduction (Figure 2A).

To test if pltR is sufficient for the autoinduction, we measured pltL promoter activity in P. fluorescens SBW25 using a reporter construct pRL-gfp, which contains the pltR gene and the pltL promoter fused with a promoterless gfp (Figure 1C) [24]. Strain P. fluorescens SBW25 does not contain pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes [34] but, if pltR is introduced, strain SBW25 has the genetic capability to activate pltL transcription as proven by induced pltL promoter activity with PG-Cl2 treatment (Figure 2B). Results show that pyoluteorin could not induce pltL promoter activity in SBW25/pRL-gfp (Figure 2B), indicating that pltR is not sufficient for pyoluteorin autoinduction. To test the possibility that PltR is sufficient for autoinduction in the presence of both pyoluteorin and PG-Cl2, both compounds were added to the cultures of SBW25/pRL-gfp. Results show that pyoluteorin did not enhance pltL expression in the presence of PG-Cl2 (Figure 2B).

Collectively, these results indicate that PltR is indispensable for the transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes, but an additional regulatory factor(s) is(are) needed for autoinduction of pyoluteorin.

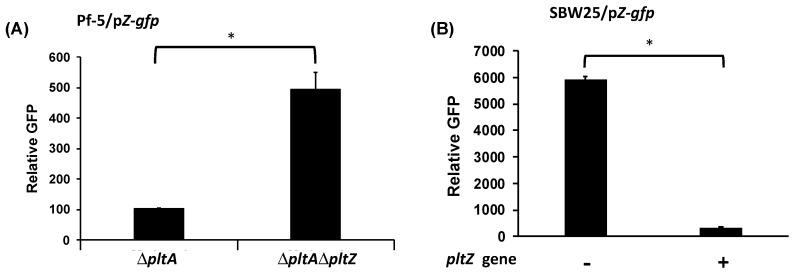

3.2. PltZ Is an Autorepressor and Directly Represses Expression of Linked Transporter Genes

In addition to pltR, the plt gene cluster encodes another transcriptional regulator PltZ (Figure 1B). Homologs of pltZ genes repress the expression of linked transporter genes in P. aeruginosa strains M18 [35] and ATCC 27853 [36]. The substrate of the encoded transporter (termed PltIJKNOP in P. protegens Pf-5) has not been demonstrated, and the function of PltZ in P. protegens has not been characterized. In this work, pltZ was deleted in the ΔpltA mutant of Pf-5, which generated a ΔpltAΔpltZ double mutant. Two reporter constructs, pZ-gfp and pI-gfp, containing the promoter of pltZ and pltI respectively fused with a promoterless gfp, were made to test if PltZ regulates the expression of itself or the linked transporter genes pltIJKNOP (Figure 1). Relative to ΔpltA mutant, ΔpltAΔpltZ mutant showed a significantly higher pltZ promoter activity (Figure 3A), indicating that PltZ negatively regulates its own transcription. We further tested pltZ promoter activity in strain P. fluorescens SBW25 carrying a functional pltZ on the expression plasmid pME6010-pltZ. Results show that pltZ markedly decreased its own transcription in SBW25 (Figure 3B), suggesting that PltZ is an autorepressor that directly regulates the transcription of itself.

Figure 3.

Autorepression of pltZ. Promoter activity of pltZ was measured using the GFP reporter construct pZ-gfp in Pf-5 mutants (A), or in strain SBW25 with or without the presence of the expression construct pME6010-pltZ (B). Promoter activity was measured as relative GFP recorded at 24 hpi. * indicates treatments are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by the Student’s t-test. Data are means and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates from a representative experiment repeated three times with similar results.

Using the reporter construct pI-gfp, which contains gfp-fused promoter of pltI, the first gene of the pltIJKNOP transcriptional unit [37], we show that pltI promoter activity was significantly higher in the ΔpltAΔpltZ mutant than in the ΔpltA mutant (Figure 4A). These results indicate that PltZ represses the transcription of pltIJKNOP transporter genes in Pf-5. Further, pltZ significantly reduced pltI promoter activity in strain SBW25 (Figure 4B), indicating that PltZ directly represses transcription of pltIJKNOP transporter genes.

Figure 4.

Repression of pltI promoter activity by pltZ. Promoter activity of pltI was measured using the GFP reporter construct pI-gfp in Pf-5 mutants (A), or in strain SBW25 with or without the presence of expression construct pME6010-pltZ (B). Promoter activity was measured as relative GFP recorded at 24 hpi. * indicates treatments are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by the Student’s t-test. Data are means and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates from a representative experiment repeated three times with similar results.

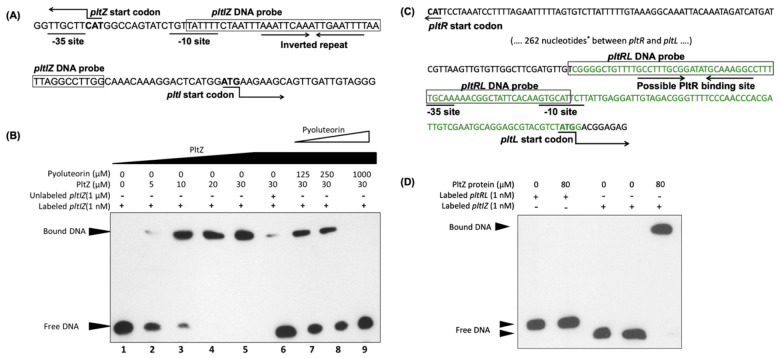

We then purified PltZ protein and tested if PltZ binds to the pltI promoter in vitro. Results of gel shifting assays show a clear shift of the labeled pltIZ DNA probe which contains pltI promoter (Figure 5A,B), but not the pltRL DNA probe that contains pltL promoter (Figure 5C,D), in the presence of PltZ protein, thus confirming the direct regulation of the pltIJKNOP transcriptional unit by PltZ. The PltZ-pltIZprobe protein-DNA complex can be disintegrated by pyoluteorin at micromolar concentrations, that are within the physiological range of Pf-5 [24], as revealed by the released free DNA probe in the presence of pyoluteorin. This result shows that pyoluteorin reduces the binding affinity of PltZ to the promoter region of the pltIJKNOP transcriptional unit.

Figure 5.

PltZ binds to the pltI-pltZ intergenic region. (A) Intergenic region between pltI and pltZ in the chromosome of Pf-5. The predicted -10 and -35 sites of pltI promoter and an inverted repeat are shown. (B) EMSA binding assay of interactions between PltZ protein, the pltIZ DNA probe (shown in (A)), and the pyoluteorin compound. The interactions were performed in 20 μL reactions at 25 °C. Lane 1 serves as a control which contains only labeled pltIZ DNA probe; lanes 2 to 5 contain labeled pltIZ probe and different concentrations of PltZ protein; lane 6 contains unlabeled pltIZ DNA fragment to compete for PltZ protein; lanes 7 to 9 contain different concentrations of pyoluteorin to test if this compound releases the pltIZ probe from its binding complex with PltZ. (C) Intergenic region between pltR and pltL in the chromosome of Pf-5. The predicted −10 and −35 sites of pltL promoter and a possible PltR binding site similar to the lys box identified in P. aeruginosa M18 [22] are shown. *: 262 nucleotides between the indicated pltR and pltL intergenic region are not shown. The DNA fragment labeled with green color was fused with a promoterless gfp to monitor the promoter activity of pltL in the reporter construct pL-gfp that was made previously [32] and used in this study (Figure 1C). (D) EMSA binding assay of interactions between PltZ protein and the pltRL DNA probe (shown in (C)). The pltIZ DNA probe used in (B) served as a positive control. The experiments were repeated at least two times.

Collectively, our results show that PltZ is an autorepressor and directly represses the transcription of pltIJKNOP transporter genes in strain Pf-5.

3.3. Pyoluteorin Interacts with PltZ and Relieves PltZ-Mediated Transcriptional Repression of pltIJKNOP Transporter Genes

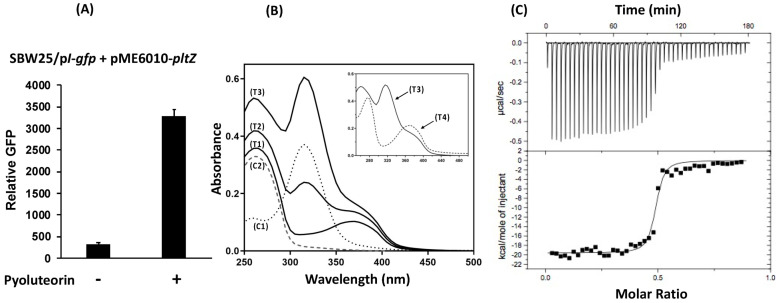

PltZ belongs to the TetR family of regulators that usually interact with small molecules or protein ligands, which then change their regulatory activities [38]. We have shown that pyoluteorin can release the DNA probe that contains the pltI promoter region from the PltZ-pltIZprobe complex (Figure 5AB). To test if pyoluteorin serves as an inducer to relieve PltZ-mediated repression of the pltIJKNOP transcriptional unit, pyoluteorin was added into cultures of strain SBW25 containing the reporter construct pI-gfp and the expression plasmid pME6010-pltZ. Our result show that pyoluteorin significantly increased pltI promoter activity (Figure 6A), suggesting that pyoluteorin is likely an inducer of PltZ.

Figure 6.

Pyoluteorin relieves PltZ-mediated repression on pltI promoter activity (A) and binds to PltZ protein in vitro (B,C). (A) Promoter activity of pltI was measured in strain SBW25 containing the GFP reporter construct pI-gfp and the expression construct pME6010-pltZ with or without the addition of pyoluteorin (1 μM). The promoter activity was measured as relative GFP recorded at 24 hpi. Data are means and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates from a representative experiment repeated three times with similar results. (B) Pyoluteorin was added into PltZ protein solution in Tris-HCl buffer at different concentrations. The absorbance profile of the mixtures was monitored. C1: control protein solution that has free purified PltZ protein. C2: control compound solution that has free purified pyoluteorin compound. T1 to T3: mixtures of PltZ protein (39 μM) and pyoluteorin compound at 7.5 μM (T1), 32 μM (T2), 57.5 μM (T3). T4 (inner figure): filtrates of T3 eluted from a Sephadex G-25 column. (C) Binding isotherm for the pyoluteorin-PltZ interaction. The integrated heat was plotted against the molar ratio between the ligand and the protein. Data fitting revealed a binding affinity of about 13.2 nM. The experiments of (B,C) were repeated two times.

We then tested the interaction of pyoluteorin and PltZ using two independent approaches. In the first spectrophotometer assay, adding pyoluteorin to a PltZ protein solution resulted in a new absorbance peak at around 375 nm (Figure 6B), likely caused by the PltZ-pyoluteorin complex. Continued addition of pyoluteorin generated a second new absorbance peak at around 315 nm, which is identical to the free pyoluteorin compound. Elution of the protein-compound solution through G25 column maintained the absorbance peak at around 375 nm, but markedly reduced absorbance at around 315 nm (Figure 6B, inner figure), likely due to the removed free pyoluteorin compound that was retained on the column. The binding of pyoluteorin to PltZ was further evaluated in an isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assay. Adding pyoluteorin compound into PltZ protein solution markedly changed the protein conformation of PltZ at a molar ratio around 0.5 (Figure 6C). Data fitting revealed that pyoluteorin binds to PltZ with a binding affinity of around 13.2 nM.

Together, these results demonstrate that pyoluteorin binds PltZ as an inducer, relieving the PltZ-mediated transcriptional repression of pltIJKNOP transporter genes.

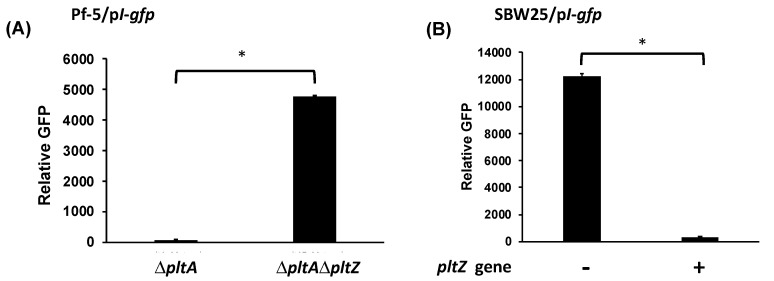

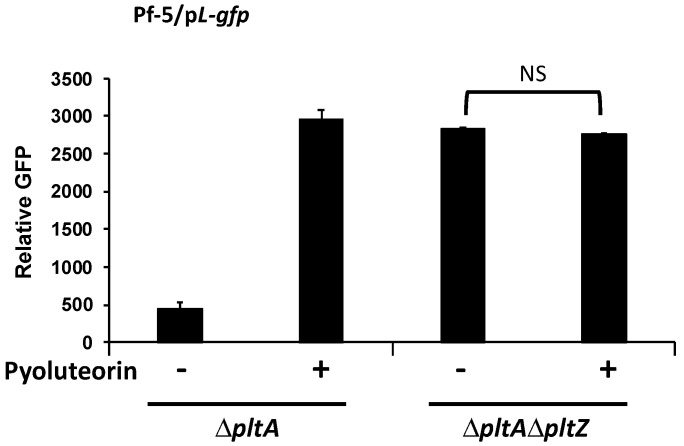

3.4. PltZ Is Involved in the Autoinduction of Pyoluteorin

Based on our results that pyoluteorin interacts with PltZ to derepress transporter genes in the pyoluteorin gene cluster, in addition to the known coordinate regulation of the biosynthesis and transport genes [37], we hypothesized that PltZ is involved in the autoinduction of pyoluteorin. To test this hypothesis, the pL-gfp reporter construct was moved into the ΔpltAΔpltZ mutant, and pltL promoter activity of the resultant reporter strain was measured with or without pyoluteorin treatment. Mutation of pltZ markedly increased the promoter activity of pltL (Figure 7), which is consistent with the previous report that pltZ negatively regulates pyoluteorin production of P. aeruginosa M18 [39]. Importantly, pltL promoter activity could not be further induced by pyoluteorin amendment in the ΔpltAΔpltZ mutant, indicating that PltZ is necessary for pyoluteorin autoinduction.

Figure 7.

Autoinduction of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes requires pltZ. pltL promoter activity was measured using the GFP reporter construct pL-gfp in Pf-5 mutants. The promoter activity was measured as relative GFP recorded at 24 hpi. Pyoluteorin was added to the cultures at a concentration of 1 μM. NS: not significant (p > 0.05), as determined by the Student’s t-test. Data are means and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates from a representative experiment repeated three times with similar results.

4. Discussion

Understanding the regulation of antibiotic production is of great interest not only in basic microbiology but also in clinical, industrial, and agricultural microbiology. Autoinduction is a widespread regulatory mechanism of antibiotic production, allowing producing microorganisms to quickly accumulate antibiotics in response to changing environmental conditions [7]. Here, using P. protegens Pf-5 as a model, we report an alternative mechanism of autoinduction by which two pathway-specific transcriptional regulators PltR and PltZ are both required for the autoinduction of the antibiotic pyoluteorin.

Both PltR and PltZ are required for pyoluteorin autoinduction but they play different regulatory roles. The requirement of PltR is consistent with previous reports that PltR protein directly binds to pltL promoter and activates transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes in P. aeruginosa M18 [22], and that mutation of pltR abolishes pyoluteorin production in P. protegens Pf-5 [21]. Together, these data show that PltR plays an indispensable role in pyoluteorin autoinduction because it is required for expression of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes. Although PltZ is also required for pyoluteorin autoinduction, it is not necessary for the basal levels of expression of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes or pyoluteorin production. Instead, mutation of pltZ enhanced pltL transcription in Pf-5 (Figure 7). Similarly, mutation of pltZ increased pyoluteorin yield and transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes in M18 [39]. These results suggest that the pathway-specific regulation of pyoluteorin biosynthesis gene expression involves at least two processes: a basal level of regulation (transcriptional activation) mediated by PltR and a higher level of regulation (autoinduction) mediated by PltZ. This mechanism differs from the known mechanisms of antibiotic autoinduction, which involves a single pathway-specific transcriptional regulator that perceives an antibiotic (or a biosynthetic intermediates) as a signal and directly stimulates transcription of the antibiotic biosynthesis genes [14,16].

The mechanisms by which PltZ mediates pyoluteorin autoinduction were not investigated in this study. However, we proved that pyoluteorin alters PltZ-mediated direct regulation of pltIJKNOP transcription with the following evidences: (1) pltZ repressed pltI promoter activity heterogeneously in strain SBW25 (Figure 4B); (2) pyoluteorin relieved PltZ-mediated repression of pltI promoter activity in SBW25 (Figure 6A); (3) PltZ bound a pltIpromoter-containing DNA probe in vitro; and (4) pyoluteorin released a pltIpromoter-containing DNA probe bound by PltZ (Figure 5).

The direct interaction between pyoluteorin and PltZ and the direct regulation of pltIJKNOP transporter gene expression by PltZ, together with the result that mutation of pltZ abolished autoinduction of pyoluteorin (Figure 7), prompt us to hypothesize that the PltIJKNOP transporter is involved in pyoluteorin autoinduction. Although the substrate(s) of this transporter remain(s) unidentified, it is known to be required for a normal production level of pyoluteorin: mutation of the transporter encoding genes decreased pyoluteorin yield in strains Pf-5 and M18 [37,40]. Bioinformatic analysis indicates that the PltIJKNOP transporter system likely serves as an exporter in pumping out intracellular metabolites [37,40]. One possible mechanism of pyoluteorin autoinduction is that the PltIJKNOP transporter, activated by pyoluteorin, exports and reduces intracellular level of metabolite(s) that is(are) repressive to transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes. Repressive metabolite(s) can be generated before pyoluteorin biosynthesis. For example, phloroglucinol (PG), the precursor of PG-Cl2 [24], is known to inhibit transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes at micromolar concentrations via an uncharacterized mechanism [41]. Repressive metabolite(s) may also be generated during pyoluteorin biosynthesis. Intermediates of many antibiotic biosynthesis pathways have been found to function as signaling molecules in self-protection and/or production of resultant metabolites [42,43,44]. Future efforts are needed to investigate if the PltIJKNOP transporter is involved in the PltZ-mediated autoinduction of pyoluteorin, and if PG and/or other potential repressive metabolites of pyoluteorin biosynthesis can be exported by the PltIJKNOP transporter and their roles in the autoinduction of pyoluteorin.

Another possible mechanism by which PltZ controls pyoluteorin autoinduction is that PltZ may directly bind to pltL promoter and repress the expression of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes. Pyoluteorin may relieve this repression, resulting in an enhanced transcription of pyoluteorin biosynthesis genes and antibiotics production. A 16-bp semi-palindromic PltZ-binding DNA motif (TNNAATTNNAATTNNA) identified in P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 [36] is also present in the pltI promoter region of Pf-5 (Figure 5A). However, this PltZ-binding DNA motif was not found in the pltL promoter region (Figure 5C), and no interaction was observed between PltZ and a DNA fragment containing the intergenic region between pltR and pltL of Pf-5 (Figure 5D) or P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 [36], suggesting that PltZ is unlikely to regulate pltL directly.

In summary, we report that pyoluteorin serves as an inducer that binds to PltZ and relieves PltZ-mediated repression of pltIJKNOP transcription. Results of this study also show that pltZ, together with the other pathway-specific transcriptional regulator pltR, is essential for autoinduction of pyoluteorin in Pf-5.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nathan Jespersen, Elisar Barbar, Brenda Shaffer, and Virginia Stockwell for their assistance. We are grateful to Jeff Chang and Jeff Anderson for their helpful discussions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y. and J.E.L.; Investigation, Q.Y., M.L., T.K., and C.P.J., Writing—original draft preparation, Q.Y.; Writing—review and editing, Q.Y., M.L., T.K., C.P.J., and J.E.L.; Supervision, J.E.L. and Q.Y.; Project administration, J.E.L.; Funding acquisition, J.E.L. and Q.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by National Research Initiative Competitive Grant 2011-67019-30192 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and Startup funds from the Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology at Montana State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kjelleberg S., Molin S. Is There a Role for Quorum Sensing Signals in Bacterial Biofilms? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002;5:254–258. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smits W.K., Kuipers O.P., Veening J.-W. Phenotypic Variation in Bacteria: The Role of Feedback Regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:259–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groisman E.A. Feedback Control of Two-Component Regulatory Systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;70:103–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilli A., Bassler B.L. Bacterial Small-Molecule Signaling Pathways. Science. 2006;311:1113–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.1121357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuipers O.P., Beerthuyzen M.M., De Ruyter P.G., Luesink E.J., De Vos W.M. Autoregulation of Nisin Biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by Signal Transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27299–27304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fish S.A., Cundliffe E. Stimulation of Polyketide Metabolism in Streptomyces fradiae by Tylosin and Its Glycosylated Precursors. Microbiology. 1997;143:3871–3876. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnider-Keel U., Seematter A., Maurhofer M., Blumer C., Duffy B., Gigot-Bonnefoy C., Reimmann C., Notz R., Défago G., Haas D., et al. Autoinduction of 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol Biosynthesis in the Biocontrol Agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 and Repression by the Bacterial Metabolites Salicylate and Pyoluteorin. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:1215–1225. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.5.1215-1225.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein T., Borchert S., Kiesau P., Heinzmann S., Klöss S., Klein C., Helfrich M., Entian K.-D. Dual Control of Subtilin Biosynthesis and Immunity in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:403–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodhagen M., Henkels M.D., Loper J.E. Positive Autoregulation and Signaling Properties of Pyoluteorin, an Antibiotic Produced by the Biological Control Organism Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:1758–1766. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1758-1766.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inaoka T., Takahashi K., Yada H., Yoshida M., Ochi K. RNA Polymerase Mutation Activates the Production of a Dormant Antibiotic 3, 3′-Neotrehalosadiamine via an Autoinduction Mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3885–3892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J., Kim J.-G., Kang Y., Jang J.Y., Jog G.J., Lim J.Y., Kim S., Suga H., Nagamatsu T., Hwang I. Quorum Sensing and the LysR-Type Transcriptional Activator ToxR Regulate Toxoflavin Biosynthesis and Transport in Burkholderia glumae. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:921–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang H., Hutchinson C.R. Feedback Regulation of Doxorubicin Biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius. Res. Microbiol. 2006;157:666–674. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitz S., Hoffmann A., Szekat C., Rudd B., Bierbaum G. The Lantibiotic Mersacidin Is an Autoinducing Peptide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7270–7277. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00723-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L., Tian X., Wang J., Yang H., Fan K., Xu G., Yang K., Tan H. Autoregulation of Antibiotic Biosynthesis by Binding of the End Product to an Atypical Response Regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8617–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900592106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwood E.J., Bibb M.J. The Antibiotic Planosporicin Coordinates Its Own Production in the Actinomycete planomonospora Alba. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E2500–E2509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305392110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas A., Morrissey J.P., Marquez P.C., Sheehan M.M., Delany I.R., O’Gara F. Characterization of Interactions between the Transcriptional Repressor PhlF and Its Binding Site at the phlA Promoter in Pseudomonas fluorescens F113. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3008–3016. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.3008-3016.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda R. Pseudomonas Pigments. I. Pyoluteorin, a New Chlorine-Containing Pigment Produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Hako Kogaku Zasshi. 1958;31:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell C.R., Stipanovic R.D. Suppression of Pythium Ultimum-Induced Damping-off of Cotton Seedlings by Pseudomonas fluorescens and Its Antibiotic, Pyoluteorin. Phytopathology. 1980;70:712–715. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-70-712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baehler E., Bottiglieri M., Péchy-Tarr M., Maurhofer M., Keel C. Use of Green Fluorescent Protein-Based Reporters to Monitor Balanced Production of Antifungal Compounds in the Biocontrol Agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;99:24–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge Y.H., Zhao Y.H., Chen L.J., Miao J., Wen L. Autoinduction of Pyoluteorin and Correlation between Phenazine-1-Carboxylic Acid and Pyoluteorin in Pseudomonas sp. M18. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2007;47:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowak-Thompson B., Chaney N., Wing J.S., Gould S.J., Loper J.E. Characterization of the Pyoluteorin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:2166–2174. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.7.2166-2174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S., Huang X., Wang G., Xu Y. Transcriptional Activation of Pyoluteorin Operon Mediated by the LysR-Type Regulator PltR Bound at a 22 Bp lys Box in Pseudomonas aeruginosa M18. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maddocks S.E., Oyston P.C. Structure and Function of the LysR-Type Transcriptional Regulator (LTTR) Family Proteins. Microbiology. 2008;154:3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Q., Philmus B., Chang J.H., Loper J.E. Novel Mechanism of Metabolic Co-Regulation Coordinates the Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites in Pseudomonas protegens. eLife. 2017;6:e22835. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King E.O., Ward M.K., Raney D.E. Two Simple Media for the Demonstration of Pyocyanin and Fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howell C.R., Stipanovic R.D. Control of Rhizoctonia Solani in Cotton Seedlings with Pseudomonas fluorescens and with an Antibiotic Produced by the Bacterium. Phytopathology. 1979;69:480–482. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henkels M.D., Kidarsa T.A., Shaffer B.T., Goebel N.C., Burlinson P., Mavrodi D.V., Bentley M.A., Rangel L.I., Davis E.W., Thomashow L.S., et al. Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 Causes Discoloration and Pitting of Mushroom Caps Due to the Production of Antifungal Metabolites. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014;27:733–746. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0311-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silby M.W., Cerdeño-Tárraga A.M., Vernikos G.S., Giddens S.R., Jackson R.W., Preston G.M., Zhang X.-X., Moon C.D., Gehrig S.M., Godfrey S.A. Genomic and Genetic Analyses of Diversity and Plant Interactions of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Genome Biol. 2009;10:1–16. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-5-r51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon R., Priefer U., Pühler A. A Broad Host Range Mobilization System for in vivo Genetic Engineering: Transposon Mutagenesis in Gram Negative Bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1983;1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoang T.T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R.R., Kutchma A.J., Schweizer H.P. A Broad-Host-Range Flp-FRT Recombination System for Site-Specific Excision of Chromosomally-Located DNA Sequences: Application for Isolation of Unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mutants. Gene. 1998;212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller W.G., Leveau J.H., Lindow S.E. Improved gfp and inaZ Broad-Host-Range Promoter-Probe Vectors. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:1243–1250. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan Q., Philmus B., Hesse C., Kohen M., Chang J.H., Loper J. The Rare Codon AGA Is Involved in Regulation of Pyoluteorin Biosynthesis in Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:497. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heeb S., Itoh Y., Nishijyo T., Schnider U., Keel C., Wade J., Walsh U., O’Gara F., Haas D. Small, Stable Shuttle Vectors Based on the Minimal PVS1 Replicon for Use in Gram-Negative, Plant-Associated Bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:232–237. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loper J.E., Hassan K.A., Mavrodi D.V., Davis E.W., II, Lim C.K., Shaffer B.T., Elbourne L.D., Stockwell V.O., Hartney S.L., Breakwell K. Comparative Genomics of Plant-Associated Pseudomonas spp.: Insights into Diversity and Inheritance of Traits Involved in Multitrophic Interactions. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X.-Q., Ge Y.-H., Zhang X.-H., Xu Y.Q. Transcriptional Repression of PltZ on Pyoluteorin ABC Transporter of Pseudomonas sp. M18. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2005;45:344–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo D.-D., Luo L.-M., Ma H.-L., Zhang S.-P., Xu H., Zhang H., Wang Y., Yuan Y., Wang Z., He Y.-X. The Regulator PltZ Regulates a Putative ABC Transporter System PltIJKNOP of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 in Response to the Antimicrobial 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1423. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodhagen M., Paulsen I., Loper J.E. Reciprocal Regulation of Pyoluteorin Production with Membrane Transporter Gene Expression in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:6900–6909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6900-6909.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuthbertson L., Nodwell J.R. The TetR Family of Regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013;77:440–475. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00018-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang X., Zhu D., Ge Y., Hu H., Zhang X., Xu Y. Identification and Characterization of pltZ, a Gene Involved in the Repression of Pyoluteorin Biosynthesis in Pseudomonas sp. M18. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004;232:197–202. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(04)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X., Yan A., Zhang X., Xu Y. Identification and Characterization of a Putative ABC Transporter PltHIJKN Required for Pyoluteorin Production in Pseudomonas sp. M18. Gene. 2006;376:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kidarsa T.A., Goebel N.C., Zabriskie T.M., Loper J.E. Phloroglucinol Mediates Crosstalk between the Pyoluteorin and 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol Biosynthetic Pathways in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:395–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y., Willems A., Au-yeung C., Tahlan K., Nodwell J.R. A Two-Step Mechanism for the Activation of Actinorhodin Export and Resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. MBio. 2012;3:e00191-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00191-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan X., Yang R., Zhao R.-X., Han J.-T., Jia W.-J., Li D.-Y., Wang Y., Zhang N., Wu Y., Zhang L.-Q. Transcriptional Regulator PhlH Modulates 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol Biosynthesis in Response to the Biosynthetic Intermediate and End Product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e01419-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01419-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong D., Wang X., Nie J., Niu G. Regulation of Antibiotic Production by Signaling Molecules in Streptomyces. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2927. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]